Chapter 9 Diffusion of the Intravenous Technique Among Narcotic Addicts

| Books - Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in United States |

Drug Abuse

The Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in the United States

Chapter 9

Diffusion of the Intravenous TechniqueAmong Narcotic Addicts

JOHN A. O'DONNELL AND JUDITH P. JONES

Note: Reprinted fromJournal o f Health & Social Behavior, 9:120-130, 1968

Addicts can administer their narcotics in a variety of ways. Opium and its preparations can be ingested orally, in solid or liquid form. Opium has been smoked in pipes, and in the Far East heroin is smoked in the form of granules on the tip of a cigarette. Heroin has been sniffed as a powder; its fumes may be inhaled after heating. Heroin and other narcotics can also be administered by hypodermic needle, in which case there is the choice of subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intravenous(mainline) injections.

The most common pattern of narcotics use in the United States today is the intravenous (IV) injection of heroin. The IV route of administration has been used by addicts long enough to seem to have an indefinitely long past. But in fact its history is short. In the course of an earlier study of addicts, one subject told the writer that in his day (the 1920's) addicts did not use the IV route; indeed, they tried to avoid hitting a vein because they considered it dangerous. A review of the older literature, which will be summarized later, suggested that he was correct; before 1930 there were few references to IV use. But by 1945 it was the usual route of administration.

This change, from little to much use of the IV route, can be viewed as a case of diffusion, which has been defined' as "the acceptance, over time, of some specific item-an idea or practice -by individuals, groups or other adopting units, linked to specific channels of communication, to a social structure, and to a given system of values, or culture." The IV route was accepted over a time period of some fifteen to twenty years; it is a highly specific and easily- identified practice; individual drug users were the adopting units. Whether or not the remaining elements of the definition apply to the spread of IN' use is an empirical question to which part of this study is addressed.

Hospital Admissions Over Time

To examine how IV use changed over time within one defined population, a sample of Lexington addict admissions was selected. The sample consists of 700 men and 311 «~omen. The men include one hundred first admissions during each of seven years, at five year intervals-1935, 1940. . . 1965. Within each year, twenty five are whites from the South and twenty-five whites from all other' states. This split was selected because it has been established that the Southern pattern of addiction has long differed from that in the rest of the country.' No similar split could be used for Negroes, since few in any year have come from the South. The split among Negro men was that twenty-five were selected from New York City and twenty-five from the rest of the country on the chance that this would produce differences.

Women were not admitted to the hospital until 1941, and were sampled, in the same race-residence subgroups, only for 1941, 1945, 1955, and 1965. This produced a sample of 200 white women but only 111 Negroes, since no Negro women were admitted in 1941 and only 11 in 1945.

The sample was of first admissions only and was selected by taking the first twenty-five in the specified years who met the race and residence requirements, with the following exceptions:

1. The male sample for 1935 and the female for 1941 were selected backward from the last admissions in those years. When the hospital opened in May, 1935, its first few hundred patients were transfers from Federal prisons. These admissions might havebeen based on selective factors different from those that determined later admissions; the same reasoning applied to the first women admitted.

2. In several years there were few Negro admissions. Some cases were selected from adjacent years for male Negroes for 1935 and 1945, and Negro women for 1945.

3. Patients were excluded if they had used only marihuana or cocaine; the sample consists of narcotics users only.

4. Puerto Ricans and Mexicans were excluded, to avoid a complicating cultural factor; there were few such admissions in the early years, not enough for a separate subgroup.

5. A few patients were excluded because their records had been transferred to other institutions, so that insufficient data were available for the study.

In technical terms the sample is not a random sample of all Lexington addict admissions because of the exceptions described. It could not be determined if a patient met all of the criteria until his hospital record was examined, and it would have been impractical to examine all. But the criteria were established before cases were examined, so no known bias entered the selection, and it is reasonable to accept the sample as representative of Lexington addicts over the thirty-year time period covered.

The more important question is to what extent Lexington admissions were representative of addicts in the United States, and this question cannot be answered because the selective factors that determined which addicts entered the Lexington hospital are not known. No assumption of representativeness need be made, however, since the sample data will be used only for a restricted purpose, to establish that involvement in a drug subculture can reasonably be hypothesized to have been a factor in the diffusion of IV use. For estimating the timing of this diffusion, the data will be treated as only one case, to be compared with data from other studies.

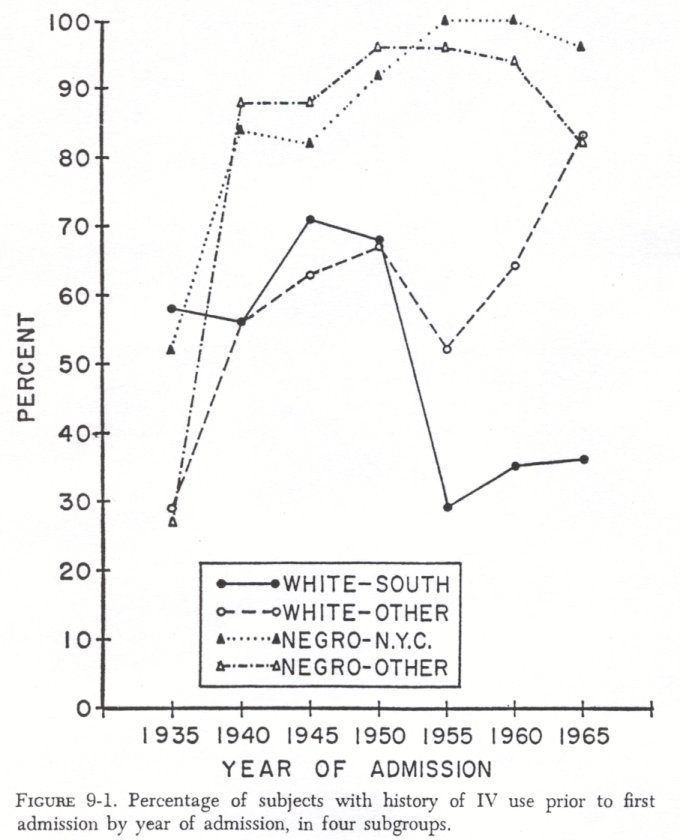

Figure 9-I shows for each of the seven years and each of the four male subgroups the percentage of all subjects for whom the route was known, who had used the IV route prior to first admission.

1. Whenever IV use began, by 1935 it was seen in 42 percent of men admitted to Lexington. At that time the differences between the races and within race by residence were not significant.

2. The diffusion of IV use after 1935 was more rapid among Negroes, rising from 40 percent in 1935 to 86 in 1940 and then more slowly to 94 in 1950. In no year was the difference between the two Negro subgroups significant. The rise was slower for whites, from 44 percent in 1935 to about 67 in 1945 and 1950. Then it continued to rise for other whites but dropped sharply, and remained low, for whites from the South.

3. With race controlled, in data not included here, the women do not differ much from the men, but the differences are consistent enough to suggest that diffusion was somewhat slower among women than men.

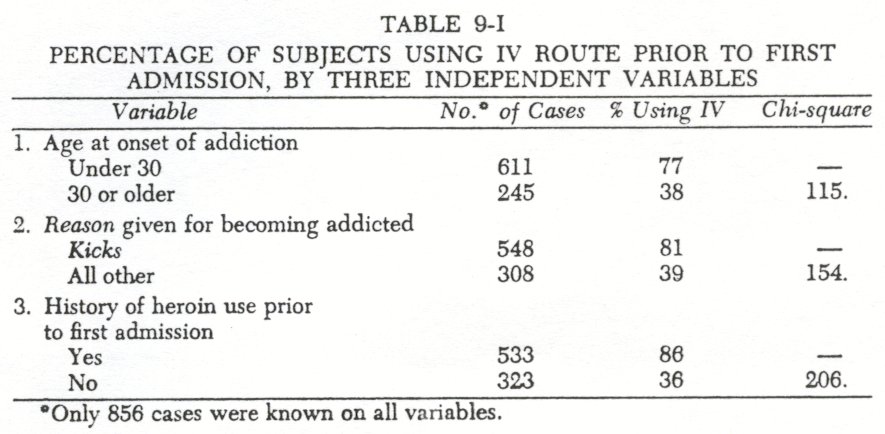

The hospital records of the 1,011 subjects were searched for data which might be treated as independent variables, with IV use as the dependent variable. Only nine independent variables were recorded consistently enough to be useful, and of these only three will be discussed here.

Table 9-I shows that IV use was far more frequent among those subjects who had used heroin; who had first become addicted through using narcotics forkicks ( as against medical treatment or treatment of alcoholic excesses, the only other categories which could be coded); and who had become addicted before age thirty. There are interactions among these variables and with other variables which need not be discussed here. Even when all nine independent variables are simultaneously controlled, these three have independent and statistically significant associations with IV use.

The conceptual significance of these three variables is that they can be considered as indicators of involvement in a drug subculture. In the time period covered, heroin was available only in the illicit drug market. Beginning narcotics use for kicks and early onset of addiction also indicate involvement because they are normally associated with introduction to narcotics by addicts in peer groups.3

Accepting the three variables as indicators of involvement in a drug subculture, their associations with IV use suggest that involvement may have been a determinant of IV use. This hypothesis can be tested directly by examining readmissions within the sample.

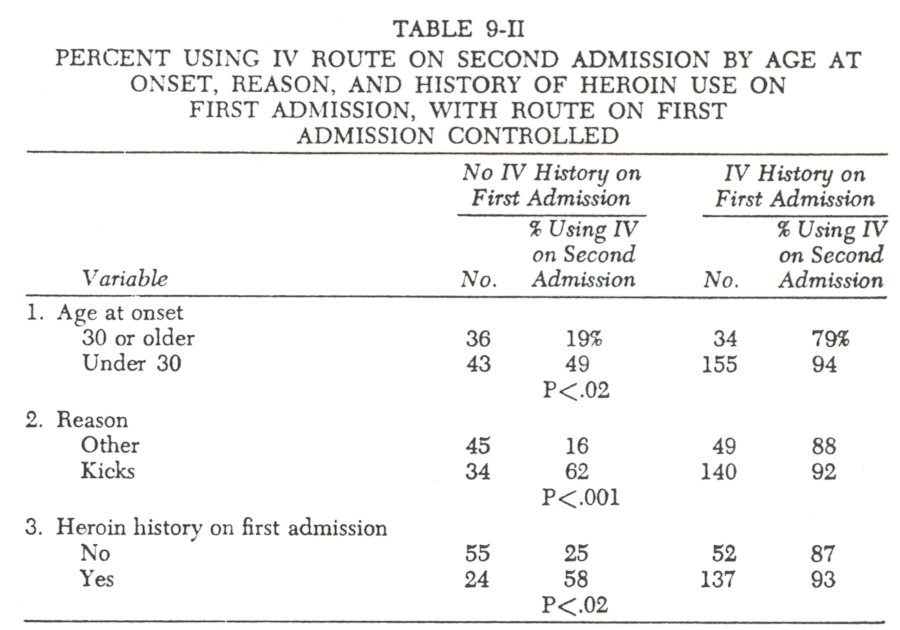

Of the 1,011 subjects in the sample, 341 had one or more later admissions. Of these, 268 could be classified on all three variables and on whether or not they had a history of IV use on first admission and on second admission. IV use on second admission can therefore be treated as the dependent variable and the others as independent. It is necessary to include IV use on first admission as an independent variable. It is the best predictor of IV use on second admission; of 189 subjects with such a history on first admission, 91 percent were still using IV on second admission; of 79 who had not used the IV route before first admission, 35 percent shifted to this route by the second admission.

The numbers are too small to look at each variable with the others controlled, so Table 9-II controls only IV use on first admission and examines the effect of age at onset, reason, and heroin history on shifts to and away from IV use. It is clear from the left side of the table that each of the three variables is associated with shifts to IV use. If onset was at age thirty or later, only 19 percent (7 of 36 cases) became IV users, while of forty-three subjects with earlier onset, 49 percent became IV users. Similarly,starting drug use for kicks and a history of heroin use were also associated with more shifts to IV use. Further, while numbers are too small for statistical tests, the effects of these three variables seem to be at least partly independent and additive; of twenty-eight subjects negative on all three, only 11 percent shifted to IV use, while of seventeen positive on all three, 71 percent shifted.

The differences on the right side of Table 9-II are much smaller and are suggestive rather than significant. The outstanding fact is that IV use, once adopted, tended to continue, with only 9 percent of those who had been IV users on first admission shifting away from that route by second admission. But fewer had shifted from the IV route if onset was prior to age thirty, or use had started for kicks, or if there had been a heroin history.

The analysis therefore establishes the three variables as prior conditions favoring shifts to IV use between first and second admissions and makes it reasonable to assume that they played the same role for the initial shift to IV use in the entire sample. The data are therefore completely consistent with the hypothesis that the drug subculture furnished the specific channels of communication, the social structure, and the system o f values which facilitated the spread of the IV route.

An alternative explanation might be that IV use is not an independent item to be explained but that it is part of a complex in which early onset for kicks and use of heroin are inextricably intertwined with IV use. This alternative can be ruled out. Using only the males for analysis, curves showing percentage with history of heroin use do not resemble the curves for IV use in Figure9-1. The Negro males were heroin users before the rise in IV use began; 88 percent had a history of heroin use in1935, and the curves are almost flat, at over90 percent, for the remaining years, except for a dip in1945, when the percentage dropped below the percentage of IV users. This dip is probably due to World War II shipping problems which reduced the availability of heroin. The percentage of heroin histories for whites from the South was only33 in1935, when almost60 percent were already using the IV route, and has steadily declined, while IV use first increased until about1950 and then declined but not as low as the heroin curve. For other whites, the1935 to1940 and1955 to1960 increases in IV use are paralleled by increases in heroin use, but the curves are not similar in the remaining time intervals.

Similarly, if onset for kicks is graphed, the curves for Negro and white Southern males are essentially flat and bear no resemblance to the curves in Figure9-1. Again, other whites show a curve for kicks which parallels the IV curve for1935 to1940 and for1950 to1965.

Finally, mean and median ages at onset of addiction for the Negro males and for white non-Southerners show slight but steady downward trends, and for white Southerners a more marked upward trend, over the thirty-year period, but no changes which resemble those of Figure9-1.

The analysis to this point may be accepted as only suggesting that involvement in a drug subculture facilitated the spread of IV use. Data to be presented from other studies will support this interpretation. Further, the analysis suggests that the increase in IV use began before1935 and that most of the increase took place between1930 and1940. This can be checked against other studies.

When Diffusion Occurred

An exhaustive review of the addiction literature up to1925 does not even mention the IV route except in a historical aside, and this does not refer to routes used by addicts.' Indeed, these writers list as one of the advantages of heroin, from the addict's viewpoint, that it required no equipment; it was sniffed.'

In the Lexington sample described above, no use of the IV route could be dated before1929, and that was in only one case. In no more than three or four others did use as early as1930 seem probable. It is unlikely, however, that this sample would include the earliest use of the IV route by addicts. Several references in the literature' suggest that intravenous injection of heroin began in Cairo, Egypt, about1925, was adopted by addicted seamen and in turn by addicts in maritime cities.

But1925 seems a little too late, since in the earliest reference this writer has located there is evidence for a slightly earlier start. In describing the physical thrill which follows an injection of morphine or heroin, Kolb mentioned? in passing that "as the intensity of this thrill wanes with increasing tolerance, some resort to injections directly into the vein in order to bring it out in full force again." Kolb's paper was published in October,1925. With allowance for the normal lag between data collection and publication, it indicates that a few addicts used the IV route before1925.

But they must have been very few, since other studies indicate that the IV route was rarely used before1930. Lamberte distinguished between the first route and the current route used by318 addicts. IV was the current route for eleven(3.4%) but was not mentioned among the first routes. Light and Torrance' reported two IV users out of an unspecified but fairly large number; IV plus sniffing, smoking, and oral administration amounted to only5 percent of cases. Hall" reported that four of fifteen morphine addicts, but sixteen of eighteen heroin addicts were IV users, among women prisoners in Illinois. In his study of Chicago addicts identified as late as1934, Dail' reports that 1.9 percent of1,587 addicts were using the IV route. Helpern and Rho lz suggest that IV use in New York City began about1933, when an epidemic of malaria broke out among addicts and was traced to the sharing of unsterilized syringes for IV injection. It may be noted in passing that this is direct evidence of the existence of a drug subculture and suggests that IV use, as well as malaria, was spread within the subculture.

These references make it clear that IV use w-as infrequent before1930 and probably until1932 or1933. But the data presented above on the Lexington sample suggest that it became a fairly frequent phenomenon by1935 and then increased greatly to1940. Within a few years Pescor" was describing male patients in the Lexington hospital as preferring the IV route, white women preferred the subcutaneous route. Zimmering et al.," described sniffing, subcutaneous, and then IV use as the usual sequence among twenty-two adolescent addicts in New York. By the late1940's there is no dearth of references; IV had become the usual route of administration."

It may be inferred, then, that IV use began in the United States about1925 and spread quite slowly until the early1930's. Probably by 1940 and certainly by1945, it had become widespread. The data on Lexington admissions between1935 and1945 can reasonably be taken as an indication of the rate of increase in these interim years, not because such admissions are assumed to be representative of all addicts but because they seem to fit so well between the dates that can be documented from other sources. The combined data suggest that as late as1930 no more than3 or 4 percent of addicts used the IV route. By1932 or1933 there was an appreciable increase which grew to about40 percent by1935, the first date for which Lexington admissions furnish firm data.

How Diffusion Occurred

To obtain further data on early use of the IV route and how it spread, patients in the Lexington hospital in late1966 were screened to identify those whose drug use had begun before1930. Five were identified and interviewed.

The first was a white man from a small town in Virginia. Drug use began about1922, at age twenty. He and a friend, who was a soda jerk in a drugstore, were drinking heavily, and the friend supplied paregoric to help them sober up. When the friend was fired, the patient sought and found a physician who would dispense morphine and began to use it regularly by the intramuscular route.

Some ten to twelve years later he hit a vein accidentally and after recovering from initial fright, decided he liked the effect better. Because he preferred the effect and for fear that a large dose intended for IM use would be dangerous if he again hit a vein, he began to use smaller doses IV. He has continued to use the IV route ever since, except that in recent years, when it was difficult to obtain, he would use paregoric and take it orally.

Another white man was from Terre Haute, Indiana. His drug use began in1924, for kicks, with the first drug supplied by addict friends. At some later date (possibly as early as1925), another addict in Terre Haute hit a vein accidentally. After the initial terrifying effect wore off, he recognized that part of the experience had been pleasurable. He experimented with a smaller dose IV, liked it, and very quickly this patient and all of the addicts in Terre Haute were using the IV route. (Note that in this and the following three cases the IV route was learned from other addicts. Each is an example of how involvement in a drug subculture facilitated the spread of the IV route.)

The third was a white man from New York City, whose drug use began in1912, at age sixteen, with opium smoking. About two years later he shifted briefly to its oral use, then began sniffing heroin and cocaine in1915. "About1922 we all started taking it by injection." This was subcutaneous. IV use began about1932, when the heroin began to be diluted-"you didn't need no vein until they cut it."

In the early years he could buy pure heroin at150 dollars per kilogram; in recent years he has paid 600 dollars for an ounce "which had everything but heroin in it." He described one experience, about1938, when after an IV shot of heroin and cocaine, he went into a coma and was then "paralyzed" for seven weeks.

A 67-year-old white woman from Columbus, Ohio, became addicted in1925. All her use was subcutaneous. She tried IV once at the suggestion of addict friends and did not like it. This was around1935. She knew of no use of the IV route among addict friends until that year.

Another woman, from North Carolina, began using narcotics about1919. Her husband had been an addict since1918. Use was intramuscular until1932, when she saw her husband use IV, tried it, and continued it. The husband's use of the IV route was at least as early as1931, but they had been separated between 1921, when he was still using intramuscular injections, and1931, and she could not date his beginning use of IV between these limits.

All interviews are consistent with a start of IV use in the1925 to1930 period. They are of even more interest in suggesting how it began, through the accidental "discovery" of the IV route, and in the fact that the same discovery was made independently in at least two different places.

When a narcotic is injected beneath the skin, there is clearly some small probability that it will be injected into a vein, even if the addict does not intend this or tries to avoid it. Since thousands of addicts were injecting drugs in the1920's, four or five times a day, it was inevitable that the discovery would be made fairly often and in many different places.

The "discovery" implies prior knowledge. If an addict did not know that an intravenous shot had much different effects from an intramuscular and accidentally hit a vein, he would know that this shot was different from usual shots, but it seems unlikely that he would instantly conclude that the difference was due to hitting a vein, as happened in two cases described. Knowledge about this possibility, however, existed among physicians at least as early as 1881" and among addicts by the 1920's and probably much earlier. That hitting a vein could be dangerous, even fatal, was also widely known among addicts.

By 1925 to1930, therefore, many addicts would be able to guess, when one shot differed greatly from earlier ones, that a vein had been hit. The hits would occur from time to time, by the laws of probability. If, after recovering from his fright, the addict decided he had liked part of the experience, he might try to recapture that part with a deliberate IV shot, using a smaller dose. If this experience was a gratifying one and if he was in contact with other addicts, he would pass the word along, andthey too would try it.

The explanation is plausible, but it leaves a question. The hypodermic needle has been used by addicts for almost one hundred years." Why did accidental injections into veins not lead to the spread of the IV route long before1925? A combination of facts may be suggested as an answer.

The probability of hitting a vein by accident depends, of course, on using a needle to administer the drug. While the needle had long been used, it did not become the most common method until some time after1914. The literature of the nineteenth century usually refers to opiumeaters andmorphine eaters. In1914 Lichtenstein" reported that in New York City sniffing was the most common method of administration, with hypodermic use second, and smoking and oral use next.

A second factor may have been that until the1920's hypodermic use was most frequent among addicts who had started drug use in the context of medical treatment. This is consistent with the Terry and Pellens statement that as of1925, heroin users who were most likely to include the kicks addict and the subcultural addict were sniffing the drug. Note that the third case cited above dates the shift to the hypodermic needle, among a New York group who were clearly kicks users, in 1922.

The relevance of this lies in an assumption that the addict who was consciously using drugs for pleasure would be the most likely to note and adopt a more pleasurable technique. But kicks users could not make the discovery if they were sniffing the drug. Medical addicts, on the other hand, would include many who perceived themselves as taking medicine for an illness. If they accidentally hit a vein, they might fail to perceive the pleasurable aspect or might not seek to repeat it by deliberate IV shots because this would threaten their self-concept. If there is anything in these speculations, the discovery of the advantages of the IV route had to wait until kicks addicts had shifted from sniffing to a needle route.

Another factor was almost certainly involved. Forty or fifty years ago addicts were taking doses which were enormous by today's standards. This was relevant in two ways. First, as the third case cited above suggests, the pleasurable effects of large doses of pure drugs were sufficient, and the additional pleasure of IV use relatively small. Second, the same case furnishes an example of the fact that large doses in the vein were dangerous and frightening. When a vein was hit, the addict might not live to tell about it, or the terrifying aspects might so overwhelm the pleasurable as to produce no desire to repeat the experience. To the extent that this factor applies, the spread of the IV route had to wait until narcotics became more difficult to obtain, so that doses were smaller, the pleasurable aspect of a vein hit could outweigh the negative aspects, and the addict could live to contribute to the diffusion of the IV route.

In short, discovery of the advantages of the IV route may have depended on a combination of relatively small doses, relatively large numbers of addicts using the needle, and especially on relatively large numbers of kicks addicts using it. This combination did not occur until the1920's, probably about1925. It was then followed, within a short time, by the discovery that the IV shot was more enjoyable, and by a very rapid spread of the technique among addicts.

One may ask whence the spread began. One possibility, made obvious by the cases cited above, is that IV use was discovered in several or many different places at about the same time and spread from each of these. But this study establishes that the spread could be very rapid, and the technique could have spread from one central place where the discovery was first made. This study furnishes no data to support a choice between these alternatives. But it does suggest that if IV spread from one place, its use started among white addicts in the South.

In1935, of eight heroin users in the group of white males from the South, seven were IV users. In the other three groups combined, twenty-four out of fifty heroin users were IV users. The difference is significant at the.04 level. Among men who did not have a heroin history in1935 and1940, nineteen of thirty seven white Southerners were IV users, against two of twenty-six in the other three groups combined. This difference is significant at the .001 level. If IV use did not begin among whites in the South, at least it became common among them before it did among other addicts.

Preference for the IV Route

Not all addicts prefer the IV route; one of the cases cited above is a woman who tried it and did not like it. But most of the subjects in this study did prefer it, as evidenced by the fact that almost all who tried it stayed with it. Shifts away from the IV route were explained by saying the veins were "used up" or by recent oral use of paregoric or other exempt narcotics when heroin and other potent narcotics could not be obtained. The reason given for preferring IV to other routes, by the patients cited above, was that it was more pleasurable. The one common element in their descriptions of this increase in pleasure was the more rapid effect of IV injection.

A factor of some importance in the current preference for the IV route and perhaps in its initial spread may have been economic. A given dose is more perceptible, taken IV, than by other routes. Studies of addicts' ability to distinguish between heroin and morphine have shown that many could not distinguish between them, and many expressed no great liking for either drug when it was given subcutaneously."' But in the same study it was found that addicts could distinguish between the drugs when given IV and that almost all then liked both drugs. Whether or not they could identify the drug correctly, the addicts almost always recognized that they had received some opiate, even at low doses, and always at slightly higher doses. When an addict today buys and injects an unknown white powder, the IV route enables him to feel he has used a narcotic, a fact of which he might not be sure if he used another route of administration.

Thus preference for the IV route deserves further study. Theliterature sometimes points out that up to a few decades ago some opiate users in the Far East seem to have led fairly normal lives. It has also been said that morphine users in the United States in the nineteenth century were no great social problem, at least in the sense that relatively few of them became criminals.' But the heroin user of today is a problem, and a large number are criminals.

This might be explained by calling opium relatively innocuous, morphine more dangerous, and heroin especially dangerous and more addicting. Or it might be explained as reflecting the different climates of opinion within which drug use occurred, from acceptance in the East, to mild disapproval in the nineteenth century, to marked disapproval and harsh punishment today. Or, the explanation might be that opium use was part of an accepted social ritual and that much morphine use was perceived as the taking of a medicine by ill individuals, while heroin use, especially by the IV route, indicates membership in a markedly deviant subculture. All three of these explanations, especially the last two, seem plausible.

But an additional explanation might lie in the fact that opium was smoked or eaten, morphine eaten and later used subcutaneously, while heroin is now taken intravenously. If the addiction process is largely conditioned learning, as Wikler2' has suggested, the rapid and clearly perceptible drug effects from an IV shot would be a more effective reinforcement and might fix the habit more firmly than the earlier routes of administration. If current experiments with maintaining addicts on methadone are found to be effective, at least for some addicts, in reducing their criminal behavior and enabling them to work and otherwise function effectively, this may be due not only to differences between heroin and methadone, or between illegal and legalsources, but also to those between IV and oral administration.

Summary

IV use seems to have started in the United States about1925, possibly among white addicts in the South. The fact that it was not widespread before 1930 seems to be due to a combination of factors, which include fairly high availability of narcotics, the dangers of IV injection of large doses, and the fact that users of the hypodermic needle, who alone could discover that the IV route increased pleasure, were least likely to have the self-concept of using narcotics for pleasure. Gradual decreases in supply led to smaller doses and to use of the hypodermic needle by kicks users as a more effective route of administration. They were then able to recognize that intravenous injection was even more pleasurable than subcutaneous, when shots were accidentally made into a vein.

This combination of factors occurred about1925, and the IV route, spread very rapidly between1930 and 1940. The diffusion was associated with heroin use, onset of addiction at an early age, and use for pleasure. These associations are interpreted as suggesting, and data from other studies as supporting, the hypothesis that involvement in a drug subculture facilitated the spread of IV use and today accounts for differences in its prevalence among addicts.

It is suggested that IV use is preferred by addicts both because they find drug effects more pleasurable when so administered and also because it may be needed to make perceptible the effects of today's highly diluted heroin. It is also suggested that addiction today may be more deleterious to the addict and to society than in past times and other places because IV has replaced less effective routes of administration.

1. Katz, Elihu, Levin, Martin L., and Hamilton, Herbert: Traditions of research on the diffusion of innovation.American Sociological Review, 28:237-252, 1963.

2.Chapter 5.

3. Terry, Charles E., and Pellens, Mildred:The OpiumProblem. New York, Bureau of Social Hygiene, 1928, pp.114,134-136,481-482; Clausen, John A.: Social Patterns, Personality and Adolescent Drug Use. In Clausen, John A., and Wilson, Robert N. (Eds.): Explorations in SocialPsychiatry. New York, Basic Books, 1957, pp.241-245; Chein, Isidor, Gerard, Donald L., Lee, Robert S., and Rosenfeld, Eva.The Road toH. New York, Basic Books, 1964, pp.149-158; O'Donnell, John A.: The rise and decline of a subculture.Social Problems, 15:73-84, 1967.

4. Terry, and Pellens, op.cit., p.64.

5. 1bid., p.484.

6. Adams, E. W.:Drug Addiction. London, Oxford University Press, 1937,pp.88-89; Helpern, Milton, and Rho, Yong-Myun: Deaths from narcotism in New York City. New York State Journal of Medicine, 66:2392-2393, 1966.

7. Kolb, Lawrence: Pleasure and deterioration from narcotic addiction.Mental Hygiene, 60:699-724, 1925.

8. Lambert, Alexander: Report of Committee on Drug Addiction.American Journal o f Psychiatry, 87:433-538, 1930.

9. Light, Arthur B., and Torrance, E.C.: Opium Addiction. Chicago, American Medical Association,1929-1930, pp.9,77.

10. Hall, Margaret E.: Mental and physical efficiency of women drug addicts.

Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 33:332-345, 1932.

11. Dai, Bingham:Opium Addiction in Chicago. Shanghai, China, The Commercial Press,1937, p.61.

12. Helpers and Rho, op. cit.

13. Pescor, Michael J.: A comparative statistical study of male and female drug addicts.American Journal of Psychiatry, 100:771-774, 1944.

14. Zimmering, Paul, Toolan, James, Safrin, Renate, and Wortis, S. Bernard: Heroin addiction in adolescent boys, Journalof Nervous and Mental Diseases. 114:19-34, 1951.

15. There are still wide differences among addicts in the use of the IV route which deserve study. Of1,893 consecutive addict admissions to the Lexington hospital in1985 78 percent were using the IV route. But the percentage was75 for white males and94 for Negro males;54 for white females and89 for Negro females. Of the IV users,78 percent used heroin, but heroin was used by only 10 percent of those with other routes of administration. Pushers were the source of drugs for85 percent of IV users and for20 percent of others. Ninety three percent of IV users but 87 percent of others lived in a Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area. Southern states contributed 16 percent of IV users but 54 percent of all others.

16. Hubbard, Fred Herman: The Opium Habit and Alcoholism. New York, A. S. Barnes, 1881.

17. Terry and Pellens, op. cut., pp.64-72.

18. Lichtenstein, Perry M.: Narcotic addiction. New York Medical Journal, 100:962-966, 1914. Reprinted in O'Donnell, John A., and Ball, John C. (Eds.): Narcotic Addiction. New York, Harper and Row, 1966.

19. Martin, William R., and Fraser, H. F.: A comparative study of physiological and subjective effects of heroin and morphine administered intravenously in post addicts. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 133:388-399, 1961.

20. Lindesmith, Alfred R.: Opiate Addiction. Bloomington, Ind., Principia Press, 1947.

21. Wikler, Abraham: Conditioning Factors in Opiate Addiction and Relapse. In Wilner, Daniel M., and Kassebaum, Gene G. (Eds.): Narcotics. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1965. ,

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|