Chapter 16 Death Due to Withdrawal from Narcotics

| Books - Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in United States |

Drug Abuse

The Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in the United States

Chapter 16

Death Due to Withdrawal from Narcotics

FREDERICK B. GLASER AND JOHN C. BALL

Note: The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of the staffs of the Temple University Health Sciences Center Library, the Free Library of Philadelphia, and the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Translations were prepared by Mrs. Rachel Burger, Mrs. Marion Ball, Dr. Ernst Jokl, and the Medical Documentation Service of the College of Physicians. This research was supported in part by the John and Mary R. Markle Foundation.

There is a widespread impression among both the general public and physicians that withdrawal from narcotics is extremely hazardous and that death is a not infrequent consequence. Inasmuch as our clinical impressions and research experience pertaining to opiate withdrawal did not coincide with this general opinion, we decided to undertake a critical review of the question of death occurring as a consequence of withdrawal. The present chapter reports the findings of this study.

In our review of the European and American literature as well as in our perusal of contemporary research data and reports, we were guided by the following methodological principles and substantive considerations: (a) Deathsfrom opiate withdrawal were distinguished from deaths which occurredduring the withdrawal process but not as a consequence of it ( i.e. terminal or acute illness, homicide, suicide, overdose). Ideally, the subject under study should be otherwise healthy. ( b ) Deaths which resulted from treatment itself were differentiated from deathsresulting from withdrawal. ( c ) In order to be regarded as a death resulting from withdrawal of opiates, the death should have occurred shortly after opiate use ceased and when withdrawal symptoms were at their height, usually between forty-eight and seventy-two hours after the last dose of narcotics.' In reviewing each death reported, attention was directed to the adequacy of the case material, particularly the autopsy findings.

Fifty-five Case Reports From the Literature, 1875 to 1968

With these criteria in mind the literature was searched for cases of death during withdrawal. A total of fifty-five such cases were found in the English and foreign literature dating back to 1875. It seems unlikely that every reported case was found, since many of the cases which were found were buried in reports devoted to quite different aspects of the narcotic addiction problem. It is, however, the largest number of cases of withdrawal deaths to be reported in the literature.

Cases 1 to 4. The earliest case reports found were those published in a series of articles beginning in 1875 by Dr. Edward Levinstein, Medical Director of the Maison de Sante in Berlin. 2

The date in itself is of interest, as it coincides with the coming into general use of the hypodermic syringe. Sir Christopher Wren was the first to use the technique of intravenous injection in 1656, injecting a dog with opium and Crocus mettallorum. and in the following year injecting a man with Vinum emeticum. But his apparatus consisted of a quill and a bladder. According toMacht the hypodermic syringe was first used by the Irish surgeon

F. Rynd in 1844, injecting morphine for the treatment of neuralgia. Alexander Wood of Edinburgh, whose paper on the same subject appeared in 1853, was the first person by whom "the hypodermic method was applied in a large number of cases and carefully written up and popularized," and he is often given credit for the innovation. In the same year a report appeared by the French physician Charles Pravaz of Lyons, who used a syringe for injecting aneurysms. It was his syringe which was copied by most later manufacturers.' Thus, Levinstein writes of morphinism: "It has not yet been admitted into textbooks; and only a few observations of it are recorded in medical literature .... The history of the disease is brief: it dates from the time when the method of subcutaneous injection by Pravaz's method became popular; and, in spite of the shortness of time, it has gained a wide and dangerous extension.'14

Levinstein is considered the founder of the method of abrupt withdrawal from opiates without the substitution of any other drug.' He reported four deaths in his case material as follows: "In two cases I have seen the abuse of morphia followed by marasmus and death; two other patients committed suicide."B Both Wolf' and Krueger, Eddy and Sumwaltg point out that one cannot be certain that the first two of these cases were related to withdrawal, and the two suicides cannot be considered to be the direct result of the withdrawal of the drugs. Both of these sources also report two additional suicides in Levinstein's case material which we have been unable to find. Even if found thesewould not, of course, be withdrawal deaths.

Cases 5 to 6. Five years after Levinstein's original article, Dr. Franz Müller of Gratz, Austria, published a three-part article on morphinism in the Wiener medizinische Presse.° He complained of what he saw as the dangers of Levinstein's method of withdrawal and suggested as an alternative a method which he himself had developed in which opium was substituted for morphine. Thus, the argument over the proper technique for withdrawal from narcotics dates at least to 1880. In supporting his arguments, Müller cites, albeit quite incompletely, two alleged cases of death resulting from abrupt withdrawal: ". . . In the City Hospital in Dresden a young seamstress died after withdrawal of morphine despite all the medical services employed; also reported is the case of a young physician succumbing in collapse which did not respond to repeated small doses of morphine." There are no further data, so the cause of death in these two cases is problematic. However, the fact that the physician did not iespond to morphine makes it somewhat unlikely that he was in severe withdrawal. This may have been one of the many cases of death from overdosage of narcotics, rather than withdrawal, which was mistakenly attributed to withdrawal. It was well known even at this time that addiction to narcotics was prevalent within the medical profession.

Case 7. The first case of death during withdrawal reported from the United States occurred in 1881.'° The patient was a 35-year-old woman who had been addicted to morphine for six years and took twelve grains by mouth per day. Initially her physician used Levinstein's method, but he became concerned about her condition and began to use morphine substitution. She did quite well and received her last dose of morphine on February 8th or 9th. On February 15th, "In the evening, her husband assisted her to some milk when she fell back and instantly expired."

The physician commented that "The fatal termination wasunexpected. If death had taken place in consequence of cardiac asthenia, the cause which most readily suggests itself, I should suppose it would have been present in some degree at my morning visit. No autopsy." Since the death in this case occurred a minimum of six days after the final dose of morphine in a gradual withdrawal, it would be quite difficult to implicate withdrawal in the etiology of the death.

Case 8. In 1887 a case was described in the French literature of a sixteen-year-old girl who had used morphine subcutaneously since the age of twelve for the pain of an anal fissure." She was withdrawn very slowly by the physician in charge, the treatment lasting for forty-two days. For the next twelve days she appeared perfectly well and received no medication. Then, however, "she was suddenly seized with hysterical and syncopal symptoms, and in a few hours she expired." At autopsy "traces of morphia were manifest in the kidneys, spleen and liver, as well as in the nervous centres."

Because of the latter findings the author proposed an autointoxication theory of narcosis. He felt that a portion of the morphine which the patient had taken had been stored in these organs and subsequently released, causing the death of the patient. With the advantage of a much more complete knowledge of the metabolism of morphine, more recent observers have commented: "The description of this case reads like an acute poisoning due to the taking of morphine after the loss of tolerance, rather than a withdrawal death, though the author seems not to have considered this possibility."" Thus, the finding of morphine in the various organs would not be due to its being stored there but to its having arrived there just prior to death via a surreptitious overdose.

Case 9. Prof. Dr. H. Obersteiner of Vienna described a rather complicated case of death during withdrawal in 1891.13 Thepatient was twenty-five years old at the time. He is described as having a "hereditary taint." Beginning when he was twentyone, he had been diagnosed as a "high grade hysteric" because of symptoms of globeshystericus, opisthotonos, and hallucinations. He then developed contractures and a hemianesthesia on the left side. Because of the pain from the contractures he was given morphine. The symptoms subsided in a year, but the addiction to morphine continued and finally brought him to the hospital for treatment. This is described as follows:

The withdrawal, in 1886, was carried out with relative speed and ease, so that after 6 days he was completely withdrawn from morphine. At this time there occurred slight heart cramps; they were not, however, alarming, particularly as they soon disappeared and the patient recovered very quickly, having no desire for morphine. After two days, he decided .to go into the garden of the hospital; in the next two days he seemed to recover physically, but experienced the following night a most unexpected heart paralysis.

Death, therefore, occurred at least ten days after the beginning of treatment and at least four days after the last dose of withdrawal medication. Moreover, Obersteiner apparently felt that the patient had a preexisting cardiac condition. He remarked that "patients with weak hearts, therefore, or those who have organic changes in the circulatory system, should always be kept out of withdrawal treatment." In the last paragraph of the article he states: "In one case, which was described earlier, is found the proof in this point-that the heart patient should not try a total withdrawal program." When these impressions, the timing of the death, the bizarre preexisting symptomatology, and the unknown nature of the "hereditary taint" are considered, it is difficult to call this a death due to withdrawal.

Case 10. Antheaume and Mouneyrat in 1897 reported the case of a forty-two-year-old man who had been a morphinist for eight years. His peak intake had been a rather remarkable combination of four grams of morphine and three grams of cocaine per day, although for the last two years he had not used cocaine and had taken only two grams of morphine per day. They state:

It was subsequently possible to perform a progressive morphine deprivation treatment using the semi-slow method without any noticeable incident. At first it appeared that suppression was well tolerated.

However, fourteen days later, the patient died suddenly without it being possible to anticipate this event in any way.14

Examination of the tissues chemically revealed morphine in the brain, liver, and kidneys, and the authors explain this in the same manner as did their countryman and predecessor B. Ball in Case 8. But in this case as well, it seems likely that the death was due to overdose after loss of tolerance, assuming that the patient was not still being given morphine for withdrawal ( it is not clear whether "fourteen days later" means fourteen days after the beginning or after the end of the withdrawal). No further clinical or autopsy data are given in the balance of the paper, which is principally devoted to the methods of extracting morphine from body tissues.

Case 11. Dr. Neil Macleod, a British physician practicing in Shanghai, was the originator of the sleep treatment for withdrawal from narcotics." He came upon the method through the observation of a naturally occurring case:

Early in 1897 a neurasthenic lady, addicted to the morphine habit for nine years, by accident had administered to her 2% ounces of sodium bromide in between two and three days, resulting in the bromide sleep described above, with the result that when she got over the effect of the bromide she had no craving for morphine, and had ceased to suffer from the various symptoms which had led to its use.is

He subsequently reported on the deliberate use of this technique in nine cases, mainly cases of addiction to drugs but also cases of mania.

One death occurred in this material. A physician thirty-seven years of age, addicted to morphine by hypodermic, died on the seventh day of treatment. Postmortem examination revealed consolidation of the right lower lobe, a "similar condition" at the left base, fifteen to sixteen ounces of bloody fluid in the rightpleural cavity, and a few ounces of similar fluid in the left.

Macleod concluded that the death was due to a respiratory illness: "The recent journey from the warm South into our cold weather, the enfeebled health consequent on the habits, and the bromide may have acted as predisposing causes to the acute lung ailment."17 In his paper the following year's he states unequivocally that this death was due to double pneumonia and "was the first of an epidemic of pneumonia, numbering more cases and deaths in a few months than had occurred in the previous twenty-one years of my residence in Shanghai." This, then, is a case of death during withdrawal resulting from an intercurrent illness.

Case 12. Inspired by Dr. Macleod's reports, Dr. Archibald Church of Chicago attempted to treat two cases of opium addiction by the bromide method. One almost died, and the other did die, which is probably why Dr. Church began his report with the sentence, "The purpose of this communication is to offer a suggestidn and furnish with it a very decided warning."19 The fatal case was a physician of about forty years of age who "for several years had taken morphine, whiskey, cocaine, and various other stimulants and sedatives, in combination or singly." He died on the twelfth day after treatment began, having been totally anuric for a number of hours. According to Church the cause of death was that "an old nephritis developed into an acute one and the patient finally died of uraemia." He adds that "whether the bromide contributed to this, it is difficult to affirm, although presumably it may have done so." Since death occurred twelve days after the last dose of medication, a major role of withdrawal in the death is ruled out. Church closes by recommending that this method be used only in well-selected cases and certainly not in anyone with a history of nephritis.

Cases 13 to 19. In March of 1915 the Harrison Narcotic Actwent into effect in the United States. During the following month Dr. William D. McNally, a chemist attached to the office of the coroner of Cook County, Illinois, wrote a letter to the,journal of the American Medical Association.' He noted that whereas one death had occurred from morphinism in both January and February of1915 and none in December of 1914, there had been a total of eleven deaths from morphinism in March, 1915. Four of these deaths were due to overdosage, and "seven deaths occurred indirectly from the sudden cessation of the use of morphin." Presumably autopsies were performed in all of these cases, but the results are not recorded. Dr. McNally attributed these deaths directly to the Harrison Act. Without additional information, however, it would be difficult to be certain of the causes of death in these cases.

Cases 20 to 26. Dr. Charles Sceleth of Chicago reported his method of withdrawal in the same journal the following year. 1 It consisted of the administration of a mixture whose chief components were scopolamine and pilocarpine. Although for the most part Dr. Sceleth eschewed the use of morphine in withdrawal, his mixture contained a small amount of ethylmorphine hydrochloride, a narcotic, and this may have lessened the withdrawal effect somewhat in his patients. Sceleth reported great success with this method but also seven deaths occurring among "patients first seen in collapse after long enforced abstinence or after misdirected treatment elsewhere." These cases were autopsied and showed a variety of pathologic findings, including four instances of bronchopneumonia, one of leptomeningitis, and one of emphysema. Another case is noted to have been an alcoholic in addition to his addiction to narcotics. With the timing of these deaths in regard to withdrawal unclear and the variety of pathological findings on autopsy, we conclude that there is insufficient information to be certain about the causes of death.

Case 27. Dr. E. Meyer of Kônigsberg in Prussia reported in1924 upon his experiences with eighty-two narcotic addictstreated both by the abrupt and the gradual withdrawal of narcotics.22 There was one death in this series. This was a male alcoholic fifty-seven years of age who had undergone gallbladder surgery both six and three months prior to admission and had become addicted to morphine because of postoperative pain. On admission he was noted to have an irregular pulse rate of 104. In addition his sister reported that he had "suffered from episodes of faintness accompanied by the lack of a pulse two times during the last months." Nevertheless, he was abruptly withdrawn. On the evening of the second day "the pulse was quite fair . . . when sudden heart standstill occurred, followed by exitus."

The author comments that "it was obvious that death was not caused by the immediate withdrawal of the morphine; it could have occurred in either method of treatment," since there had been difficulties with "the sudden onset of cardiac failure" using both the abrupt and the gradual regimens. His general conclusion was that his experience constituted "strong evidence that the more effective treatment of morphinism is complete withdrawal. All `weaning remedies' sometimes advertised or boasted about are useless or dangerous." This would appear to be a case in which a preexisting cardiac condition and perhaps also some degree of debilitation from repeated episodes of major surgery plus the patient's alcoholism were the major factors leading to death.

Case 28. This case brings us to one of the more interesting and exotic treatments utilized in dealing with narcotic addiction and withdrawal. In 1926 Lambent and Tilney treated 366 addicts in withdrawal with a substance known as Narcosan.23 Introduced two years earlier by A.S. Horovitz, it is described as consisting of "a solution of lipoids, together with non-specific proteins, and water-soluble vitamines: " The rationale for its use was the notion that the lipids of the central nervous system were depleted by opiate use and that the problem could be resolved by the administration of the lipids contained in Narcosan. For our purposes the following case report is relevant: "One patient, a negress, thirty-six years old, who in two previous reduction treatments had had convulsions and serious collapse, nearly ending fatally, had intense pain due to intestinal spasm, with small frequent pulse and cold extremities, with unexplained dyspnea and collapse. In spite of vigorous stimulation, the patient died fortyeight hours after beginning treatment; this was the only fatality. 1124

Kolb and Himmelsbach described the Narcosan treatment as "the most useless and harmful" of the lipoid treatments for narcotic addiction.26 Even more interesting is the fact that Alexander Lambent himself, only four years after this highly enthusiastic report on Narcosan was written, provided the evidence which led to its abandonment. He became the chairman of an earlier Mayor's Committee than the famous one which investigated marihuana under Mayor LaGuardia. Perplexed at the variety of claims made by different withdrawal treatments, Mayor James Walker appointed a committee charged to investigate the different methods scientifically so that the most effective one might be used in the public institutions of the metropolis. The committee did its work with extreme care and produced an impressive comparative report in 1930.21 The report was particularly harsh on the Narcosan treatment. Using controls which had been entirely left out of the original evaluation by Lambent and Tilney, it concluded that Nareosan ". . . did not alleviate any of the withdrawal symptoms, but on the contrary in all, especially the gastro-intestinal group, they were more severe than those in the untreated group. The combination of abrupt withdrawal and severe gastro-intestinal symptoms incidental to Narcosan treatment involves danger to life in addicts who are aged, ill-nourished,and suffering from pronounced organic disease" ( p.442 ) .

There is an additional horrendous description of the gastrointestinal effects of Narcosan on pp.498-499 of the report. With reference to the case under consideration, in the absence of autopsy findings the most parsimonious explanation of her death is that she had preexisting gastrointestinal pathology which was fatally exacerbated by the administration of Narcosan. She is therefore the first case in this series, though unfortunately not the last, whose death can be attributed to the treatment given for withdrawal rather than to withdrawal itself.

Case 29. In the same Mayor's Committee report of 1930 mentioned above is recorded one death during withdrawal, as follows: "Our only death in the ward was that of a patient who was 65 years of age, in poor physical condition, suffering from chronic cardio-vascular-renal disease, whose habit was of 36 years' duration. This patient died on the third day- of a reduction treatment when his morphine dosage had been only moderately reduced .12'

It is to be noted that this was the only death which occurred in the 318 patients who were withdrawn during this study, by the committee. The group had an average habit equivalent to three grains of morphine per day. Because of the excellence of this committee's work and because its report constitutes the only careful, comparative study of methods of withdrawal we were able to find in the literature, it may be worthwhile to look at their recommendations:

Younger addicts in good physical condition may often be given abrupt withdrawal without danger. Aged or decrepit addicts, or those suffering from severe organic disabilities, should be kept on a sufficient morphine ration in properly supervised surroundings indefinitely, as there is danger to life in withdrawing their drugs. It is inadvisable to prolong a reduction treatment so long that no withdrawal symptoms occur. A certain amount of reaction exerts a wholesome psychological influence and deterrent effect in preventing too facile relapse from the fear of suffering which drug addicts have in the exaggerated form typical of their psychoneurotic make-up.28

Case 30. In 1931 two Chinese physicians working in theJang Seng Clinic in Batavia, Dutch East Indies, reported on their search for an adequate method to treat addiction to opiates."' They had tried Macleod's sleep method but with unfortunate results. A thirty-year-old man who had been using opium for years was put to sleep by means of Somnifen ( a solution of the diethylamine salts of diethyl-barbituric acid and allyl-isopropyl barbituric acid). He lapsed into coma and died, the authors felt, from an overdose of the sedative. As they had a previous case which also went into coma but which, fortunately, they were able to save, they abandoned the sleep method. In its place they began to use the blister-serum method of Modinos, with which the better part of the paper is concerned. This is in itself a fascinating topic. The method is well discussed by Kolb and Himmelsbachs° and was one of several treatments based on the notion that narcotic addiction and withdrawal had something to do with the immune mechanism.

Cases 31-33. Drs. L. E. Detrick and C. H. Thienes published a general review of various aspects of drug addiction in November 1935. In it they stated that " `Cold turkey,' that is, no treatment at all, in the Los Angeles County jail has resulted in two or three deaths in five thousand narcotic patients ( Dr. B. Blanc, a matter of record ) ."31 No further information nor any reference to Dr. Blanc's work is given. This does not appear to be sufficient evidence to establish that the deaths were directly due to opiate withdrawal rather than a preexisting condition, foul play, or overdose.

Cases 34-36. One of the few articles in the literature dealing directly with the issue of death as a result of withdrawal appeared in March of 1937, authored by Drs. Piker and Gelperin in Cincinnati.'2Three cases are presented. The first of these was a man forty-four years old who was a paregoric drinker. He lapsed intocoma seven hours after admission, never recovered despite being given morphine, and died on the third day. There were a number of complicating factors. First, he had been given insulin by his private physician for three days prior to admission, and this was continued in the hospital. Insulin subcoma was once a treatment used for narcotic withdrawal ( for example see Piker-") based on the observation that there was often a slight hyperglycemia during the withdrawal period. Kolb and Himmelsbachs4 found that "insulin had no effect on withdrawal symptoms" and noted that "there is no reason to believe that the high blood sugar incident to withdrawal is of itself the cause of any of the symptoms." Wieder, in an excellent controlled study," also demonstrated precisely this and added that "in fact, the use of insulin may even be harmful since patients receiving it suffer from two illnesses instead of one-the hypoglycemic syndrome and the morphine abstinence syndrome."

Beyond this the patient had a very high fever and a white blood cell count of 34,000 with a marked shift to the left ( 84% polymorphonuclear leukocytes). On autopsy he was found to have lobular pneumonia, which was probably the primary cause of death. In addition, he had experienced "a generalized convulsion lasting five minutes" on the second day of coma, and at autopsy there was "cerebral congestion and edema, chronic leptomeningitis, and early degenerative changes in the pons." To attribute the death of this patient to withdrawal would be difficult indeed.

The second of Piker and Gelperin's cases is readily dealt with, for we are told that this man had no narcotics whatsoever for one week prior to his admission. He had, however, been drinking heavily, and "his condition suggested impending delirium tremens for the first two days in the hospital, and he manifested no symptoms that might have been interpreted as specifically due towithdrawal from narcotics:" Two days after admission he was found in deep coma and pulmonary edema. He was given insulin and also morphine, developed a high fever, convulsions, a terminal bronchopneumonia, and died on the sixth day of the coma. There was no autopsy.

Likewise, the third case had been a heroin addict but had used no drugs for three days prior to admission. Three hours after admission he was found in coma with labored respirations. Stimulants and morphine were administered, but he died two hours after the onset of coma. Again there was no autopsy.

After summarizing these cases in detail, Wolff" noted that their characteristic features were the coma, an unusual respiratory disturbance, and death. He noted that "morphine injections, which generally save a difficult situation during withdrawal, were without effect." His conclusions: "No special explanation is given for these recorded occurrences, and the only thing which may point to a clue is the fact that, apparently, the treatment was started without previously keeping the addicts under observation for a few days in the clinical ward."

In other words, the most probable explanation for the deaths in at least the second and third cases and perhaps in all three was death from overdosage of narcotics which the patients had either taken just before admission ( a very common habit of addicts about to face withdrawal) or which they had actually smuggled into the hospital. The clinical picture in at least the last two cases is exactly that of overdose; if case 1 did not die of overdose, he had many other reasons to die. Thus, these three cases, often cited as demonstrating the dangers of withdrawal, had actually very little to do with withdrawal at all.

Cases 37-47. As part of their excellent critical review of withdrawal treatments in 1938, Kolb and Himmelsbachg' included a section on "deaths under treament." They briefly described eleven such cases. Eight of these eleven cases were treated with hyoscine, belladonna, and purgatives. Of these methods Kolb and Himmelsbach wrote:

Treatment by these [belladonna] drugs is absolutely useless and evenharmful to addicts in withdrawal, . . . Their wide and continued use illustrates the errors that may creep into observations as to the efficacy of treatments and supports our own observation that addicts often get over the withdrawal period in spite of, rather than because of, what is done for them.... Extreme purgation is . . . illogical. The only effect of such purgation is to devitalize the patient and increase the danger of collapse and death.-18

They further concluded with reference to the fatal cases that "hyoscine, belladonna, and purgatives undoubtedly increased the distress of these eight patients and contributed to their deaths." There were also extenuating circumstances in the other three cases:

One was a woman about 60 years old with a strong habit who was given abrupt withdrawal because it was thought somehow to be morally wrong to give morphine to an addict even in treatment. One, a man 6? years of age, died under abrupt withdrawal. (Information was not definite as to whether this man collapsed in a heat cabinet.) One, a man 42 years old, with a possible but unproved heart lesion, suddenly collapsed under abrupt withdrawa1.39

Because of the complications in every case, a lack of further data, and particularly the absence of autopsy findings, none of these deaths can with certainty be attributed to withdrawal directly. In every case there existed some other factor which severely limited the individual's capacity to respond to stress.

Case 48 - Dr. Jean Swain -of the Universes=- of - Michigan advanced in 1945 the thesis that "morphine can and does produce definite irreversible changes within the nervous system."" To support this statement three cases are cited, the third of which is pertinent for our purposes. She was a housewife twenty-nine years old with a history of taking ten to twelve grains of morphine intravenously per day over a twelve-year period. She had been unable to obtain any morphine for the previous forty hours. She was begun on insulin treatment, but on the third hospital day, two hours after her last dose, she lapsed into coma, dying on the morning of the fourth day despite resuscitative measures. At autopsy there was hemorrhage throughout the lungs, but themost prominent changes were in the brain. They are summarized as being severe and chronic and as consisting of neuronal alteration and destruction and irregular perivascular demyelinization. "The myelin damage was often complete with a rupture of the myelin sheath and a complete destruction of the axon."

The author felt that the insulin administered "was an irrelevant factor which need not enter into considerations of etiology" of the lesions, which she believed to be the direct effect of the morphine. That the insulin may have contributed to the patient's demise, however, is indicated by the discussion of case 34 above. Swain's major conclusion is challenged by Isbell who wrote that "No specific pathologic changes are directly attributable to the chronic use of opiates. Such changes as do occur are probably attributable to malnutrition, abscess formations in the injection sites, and diseases not related to the addiction."41 Helpern, moreover, has recently suggested that similar lesions which he and his co-workers have found upon postmortem examination of chronic addicts may be due rather to subfatal episodes of anoxia during subfatal overdoses which occur not infrequently in the addict's career. 42

If the history was an accurate one, the patient's death occurred at a time when her most severe symptoms were already past. The additional complications of the insulin -treatment and the severe central nervous sy=stem pathology found upon autopsy make it difficult to implicate withdrawal as the cause of death in this case.

Case 49. During a study of psychosis occurring as a complication of withdrawal from morphine, Pfeffer reported an incidental death." "A patient with an organic type of psychosis died during withdrawal of the drug, and postmortem examination revealed acute and chronic meningoencephalitis of undetermined cause." Presumably, this was the cause of death in this case. Incidentally,he found that twelve of five hundred cases of withdrawal, or about 2.4 percent, developed psychotic manifestations during the withdrawal period.

Case 50. This was the case of a white, man forty-five years old "in whom severe rheumatoid arthritis with marked deformity and ankylosis had developed about 20 years previously."'4 He had begun to use one grain of codeine three or four times per day at that time because of the pain. However, this dose lad been gradually increased, and for several years prior to admission he had been using three grains of codeine every three hours, day and night, or 1,560 mg of codeine per twenty-four hours, a truly gigantic dose. Two days prior to admission "someone suddenly decided that because of the `narcotic problem' the medication would be stopped entirely." The remainder of the clinical course is described as follows:

On admission here, the patient was acutely, as well as chronically, ill. He was sweating profusely, in association with persistent vomiting and severe abdominal cramping. He was given meperidine; however, this was not effective in controlling his symptoms. Codeine was started on the second day, but the patient died shortly thereafter. Autopsy showed no findings which could be interpreted as causing death.

Further on in the paper the author states that the "cause of death was uncertain" but that the circumstances "certainly lead one to suspect strongly that codeine withdrawal was closely related to the patient's death," and still Hater, "death probably was due to the abrupt withdrawal of the drug." Of all of the cases reviewed in this study, this one conforms most closely to our methodological principles. However, it does not fulfill them perfectly, since there can be little doubt that this man's chronic and severe debilitating illness markedly impaired his capacity to deal with stress. It is also very unusual in that he was taking an extraordinary amount of a chemically pure drug.

Cases 51-55. During the two-year period from 1965 to 1967, 45,649 addicts were admitted to institutions operated by the New York City Department of Corrections, or about 16 percentof the total admissions during that period.'' Of these individuals five died during withdrawal of narcotics from acute intraabdominal catastrophies. Four deaths were due to perforated ulcers and one to acute pancreatitis. In all cases it was initially felt that the abdominal symptoms were simply due to withdrawal and the authors felt that this impression may have contributed to the fatal outcome in these cases. Differential diagnosis in these instances is extremely difficult.

For our purposes it is necessary to point out only that it is highly unlikely that these events arose de nouo at the time of withdrawal and much more probable that they represented exacerbations of preexisting conditions during the withdrawal process. There is no evidence that withdrawal from narcotics per se can cause the perforation of a viscus or the onset of acute pancreatitis.

Summary and Conclusions From Individual Case Reports

Our review of fifty-five case reports of deaths during the period of withdrawal from narcotics reveals that no case meets stringent criteria designed to exclude all cases save those which can be said to be due solely and exclusively to the withdrawal itself. The fifty-five cases appear to fall into roughly eight categories with respect to cause of death. Suicide accounted for two cases ( X3,4). Overdose of narcotics was the likely cause in at least four cases ( #7_'6,8,35,36 ) . Intercurrent illness caused three deaths ( ,.~ 11,34,49 ) . The exacerbation of a chronic illness or some other preexisting condition was responsible for eleven deaths ( # 12,27,29,45,47,48,51-55 ) . Overzealous treatment caused ten deaths ( -X28,30,37-44 ) . Other accidental phenomena caused one death (:LI-46). In two cases (#7,9) there was insufficient information to ascertain the cause of death, but it appeared unlikely that death was due to withdrawal. Finally, in twentytwo cases the reports gave insufficient information to determine precisely either the cause of death or its relationship to withdrawal ( ~ 1,2,5,10,13-19,20-26,31-33,50 ) .

This categorization and determination of the fifty-five cases is, of course, a rough approximation. It assumes, for example, that the demise of case 45 was due largely to her advanced years, that case 46 died largely because of advanced years but also because he was in fact in a heat cabinet, that case 47 did in fact have a heart lesion, and that the severe disease of case 50 was a major factor in his death. Other assumptions have been made about other cases, and they may not all be accurate or justified. Yet, the significant fact remains that no clear-cut, unequivocal case of death resulting from withdrawal from narcotics exists in this series. Indeed, the fact that the series is of such meager size is of considerable significance. Even if even one of the fifty-five cases had died a primary withdrawal death and even assuming that a number of cases were missed and that mangy- more which occurred were unreported, the total number is still surprisingly small when one considers that experience with the drug goes back to the darn of recorded history and that even experience with severe withdrawal goes back almost a century. In the last hundred years millions of individuals have been withdrawn from narcotics. Yet, we find but fifty-five cases reported of death during withdrawal. Upon careful inspection even these cases are for the most part clearly not due to the withdrawal process itself. We have another line of evidence to examine, but on the basis of this evidence alone, one would be forced to conclude that death due to withdrawal from narcotics is rare, if it indeed occurs.

At the same time it is also apparent from these cases that withdrawal from narcotics often places a definite and palpable stress upon the individual. One who is otherwise healthy or whose ability to cope with stress is not in some manner limited can probably, on the basis of this evidence, withstand the stress of opiate withdrawal without difficulty. But, for the impaired individual, whether by age or preexisting or intercurrent disease, the stress of withdrawal may combine wide other conditions to produce a fatal outcome. Still, the salient point is that these cases fail to furnish a single instance in which withdrawal alone is a sufficient cause of death.

Deaths During Withdrawal at the Lexington Hospital

The Lexington Hospital has had the most extensive history of treating narcotic addicts of any institution in the United States. It affords, then, an excellent source of data on the topic at hand: death due to withdrawal from opiates.

From the time of its opening on Way 31, 1935, up to December 31, 1966, there were 43,215 addicts treated at the Lexington Hospital. Of these patients 29,581 ( more than two-thirds) went through the withdrawal service of the hospital following admission; the remainder were federal prisoners who were no longer dependent on drugs at the time of admission.

The withdrawal techniques employed during the past thirty years have generally been those of rapid rather than abrupt withdrawal, with another opiate ( usually morphine or methadone) substituted for the drug of addiction and then withdrawn in stages. This withdrawal procedure has been quite successful, and it has been carefully reported in the medical literature .46

It is important to note here that we are considering deaths which occurred in a specialized hospital while the patient in the withdrawal service was under experienced medical care. Therefore, one might expect fewer withdrawal deaths at Lexington and a more accurate determination of the cause of death than in a less competently staffed institution. At the same time, the free voluntary admission policy of the hospital ( now ended) has resulted in the admission of some patients who were chronically or acutely ill; thus, one could expect that death following admission would not be uncommon, quite apart from the question of withdrawal deaths.

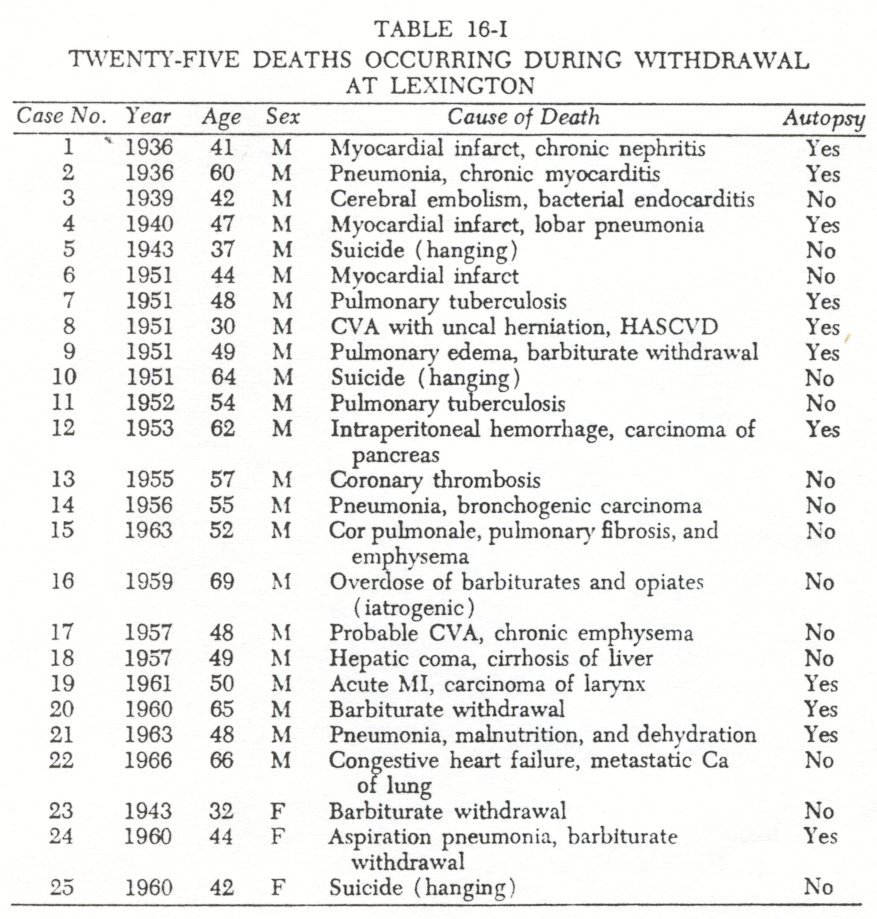

The 25 deaths which occurred during the withdrawal process at the Lexington Hospital were reviewed in the same manner as that followed in the analysis of all 385 deaths in Chapter 15. The immediate and principal cause of death was determined in each case by a detailed review of the clinical course record and, when available, the autopsy findings. After the cause of death of each patient was determined, a reliability check was done. Thisdetailed review of the clinical records, autopsy findings, and collateral data was undertaken in order to employ a standard and reliable procedure for ascertaining the cause of hospital deaths. It is relevant to note that such a systematic review often results in a different determination of the cause of death from that of the death certificate because of new medical knowledge, additional laboratory reports, and more careful investigation of the relevant case material.

The cause of death for each of the twenty-five addict patients who died while in the process of withdrawal is shown in Table 16-I. Seventeen of the deaths were due to intercurrent or preexisting disease, such as myocardial infarction or pulmonary tuberculosis. Four patients died as a result of barbiturate withdrawal, three from suicide, and one from an iatrogenic overdose of both narcotics and barbiturates. There were, then, no deaths attributed to the withdrawal of opiates.

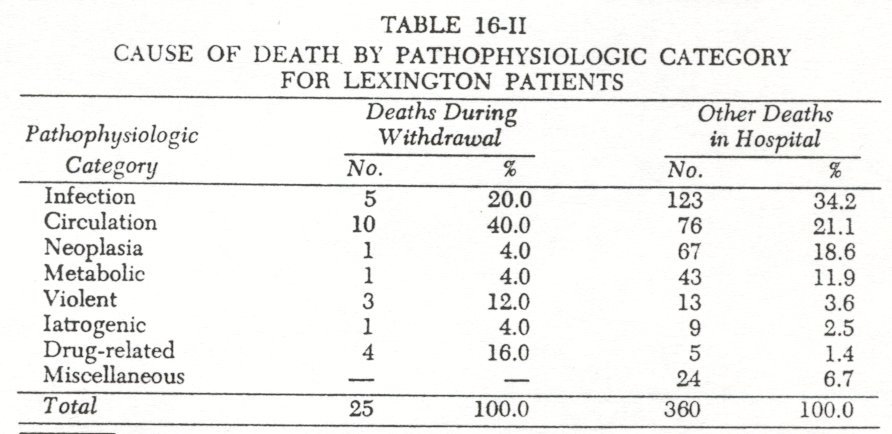

Although twenty-five deaths is a rather small number, it is interesting to compare those deaths which occurred during withdrawal with all other deaths in the hospital with respect to pathophysiologic categories ( as tabulated in Table 15-I ) . This provides us with some data as to which other stress is likely to interact with the withdrawal process and result in death. These data are presented in Table 16-II. It may be seen that individuals with circulatory problems are particularly prone to have them exacerbated during withdrawal. It also appears that, at least in this population, suicidal tendencies may be more pronounced during withdrawal than at other times. It is, of course, quite expected to find drug-related deaths more common at the time of withdrawal; all four of these in the withdrawal population were due to barbiturate withdrawal, which must be considered quite hazardous. On the other hand, it appears, as one would expect, that neoplastic and metabolic processes, and to a lesser extent infectious processes, do not tend to interact as readily with the stress of withdrawal to result in death.

To recapitulate, of the 29,581 patients4' who underwent the withdrawal process at the Lexington Hospital during a 31-year period, there were 25 deaths which occurred while withdrawal was under way. None of these twenty-five deaths was due to the withdrawal of opiates, but there were four deaths from barbiturate withdrawal. The fact that drug-induced deaths of almost every type except that of opiate withdrawal occurred at the hospital seems significant. In addition to deaths from barbiturate withdrawal, there were deaths resulting from overdose of opiates and alcohol withdrawal. It seems reasonable to conclude on the basis of the Lexington data that death resulting directly from the withdrawal of opiates is extremely uncommon and that this is so whether the addict is under medical supervision or not. Thus, many of the drug-induced deaths occurred immediately or shortly after the patient was admitted to the hospital and before effective treatment could be instituted. If opiate withdrawal were extremely dangerous without medical treatment, one would expect that there would at least be a few such deaths following admission from this cause, as there were from other causes. This did not occur. Consequently, we interpret these findings as evidence that withdrawal deaths from narcotics, whether under medical care or not, are rare.

Summary and Conclusions

In this chapter an attempt was made to assess the hazards of withdrawal from narcotics, with particular reference to the most extreme hazard, death. Inasmuch as withdrawal from narcotics is generally considered extremely dangerous and death not infrequent, we decided to investigate the question of the precise relationship between opiate withdrawal and subsequent mortality.

A search of the literature, both English and foreign, yielded a total of fifty-five cases of death during the withdrawal process occurring between 1875 and the present. Each case was carefully examined. Although it was clear that withdrawal from narcotics constituted a stress which, in combination with such preexisting factors as chronic debilitating illness and extreme old age, might result in death in certain cases, no case was found in which withdrawal from narcotics per se was a sufficient cause of death.

The experience of the Lexington Hospital from its opening in 1935 through 1966 was next examined. During that time 29,581 patients passed through the withdrawal service. There were but twenty-five deaths during withdrawal. None of these deaths, after they had been individually examined, could be attributed to withdrawal from narcotics. Withdrawal from barbiturates, however, had caused four deaths. By comparing the deaths during withdrawal with the total mortality experience at Lexington, it was possible to conclude that of the preexisting conditions which might interact unfavorably with the stress of withdrawal, two were prominent. These were circulatory problems and the presence of suicidal tendencies.

In sum, we have found little or no support for the belief that withdrawal from narcotics is a dangerous and often fatal process. Indeed, our study has shown that opiate withdrawal is an extremely uncommon cause of death among addicts. To date, we have been unable to find a single documented case in which opiate withdrawal was the sufficient cause of death. We conclude that death due to withdrawal of narcotics may not occur.

1.Kolb, Lawrence C., and Himmelsbach, C.K.: Clinical Studies of Drug Addiction. III. A Critical Review of the Withdrawal Treatments With Method of Evaluating Abstinence Syndromes. PublicHealth Reports, Suppl. 128. Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, 1938; Himmelsbach, C.K.: The morphine abstinence syndrome, its nature and treatment.Annals of Internal Medicine, 15: 829-839, 1941; Himmelsbach, C.K.: Clinical studies of drug addiction: physical dependence, withdrawal and recovery.Archives of Internal Medicine, 69:766-772, 1942.

2. Levinstein, Edward: Die morphiumsucht.Berliner kGnische Wochenschrift, 12:646-648, 1875 (transl. in theLondon Medical Record, 4:55-58, 1876); Levinstein, Edward: Zur morphiumsueht.Berliner klinische Woehenschrift, 13:183-185, 1876; Levinstein, Edward: Zur pathologie der acuten morphium-and acuten chloral-vergiftungen.Berliner klinisclae Wochenschrift, 13:388-390, 1876; Levinstein, Edward: Die morphiumsucht.Verhandlungen der Berliner medizinische Gesellschajt, 7:14-23, 1876; Levinstein, Edward: De l' abus des injections de morphine ( morphinomania ).Bulletin generate de Therapée, 90:348, 1887 ( abstracted in CanadaLancet, 9:138, 1887); Levinstein, Edward:Morbid Craving for btorphia (Die Morphiumsucht): A Monograph Founded on Personal Observation. London, Smith, Elder and Company, 1878; Levinstein, Edward: Zur pathologie, statistil:, prognose and gericht sartzlichen bedeutung der morphiumsueht.Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift, 5:599-600, 1879.

3. Macht, David L: The history of intravenous and subcutaneous administration of drugs.Journal o f the American Medical Association, 66:856-860, 1916.

4. Levinstein, Edward: Die morphiumsucht.Berliner klinische Wochenschrift, 12:646-648, 1875.

5. Wolff, P. O.: The treatment of drug addicts: a critical survey.Bulletin of the Health Organisation of the League of Nations, 12:455-682, 1945-1946.

6. Levinstein, Edward: Die morphiumsucht.Berliner klinische Wochenschrift, 12:646-648, 1875.

7. Wolff, P.O., op. cit., p.517.

8. Krueger, Hugo, Eddy, Nathan B., and Surnwalt, Margaret: The Pharmacology of the Opium Alkaloids. PublicHealth Report, Suppl. 165. Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office,1943, Part 1,p.738.

9. Müller, Franz; Ueber morphinismus.Wiener medizinische Presse, 2I:297-300, 332-334, 361-364, 1880.

10. Loveland, J.A.: Morphia habit.Boston Medical and Surgical journal, 104: 301, 1881.

11. Ball, B.: Des lesions de la morphinomanie et de la presence de la morphine dans les visceres.L' Encephale, 7:641-647, 1887. Abstract in theAmerican Journal of Pharmacy, 59:612, 1887, and inLancet, 2:892, 1887.

12. Krueger, H., Eddy, N.B., and Sumwalt, M., op. cit.

13. Obersteiner, H.: Zur therapie des morphinismus.Internationale klinische Rundschau, 5:1840-1843, 1891.

14. Antheaume, A., and Mouneyrat, A.: Sur quelques localisations de la morphine dans l'organisme.Comptes Rendus de PAcademie des Sciences, 124:1475-1476, 1897.

15. Macleod, Neil: Cure of morphine, chloral, and cocaine habits by sodium bromide.British Medical journal, 1:896-898, 1899.

16. Macleod, Neil: The bromide sleep: a new departure in the treatment of acute mania.British Medical Journal, 1:134-136, 1900.

17. Macleod, Neil: Cure of morphine, chloral and cocaine habits by sodium bromide.British Medical Journal, 1:897, 1899.

18. Macleod, Neil: The bromide sleep: a new departure in the treatment of acute mania.British Medical journal, I :134, 1900.

19. Church, Archibald: The treatment of the opium habit by the bromide method.New York Medical Journal, 71:904-907, 1900.

20. McNally, William D.: Effects of the Harrison Law.Journal of the American Medical Association, 64:1264, 1915.

21. SceIeth, Charles E.: A rational treatment of the morphin habit.Journal of the American Medical Association, 66:860-86°, 1916.

22. Meyer, E.: Uber morphinismus, kokainismus, and den missbrauch anderer narkotika.Medizinische Klinik, 20:403-407, 1924.

23. Lambent, Alexander, and Tilney, Frederick: The treatment of narcotic addiction by Nareosan.Medical Journal and Record, 124:764-768, 1926.

24. Ibid., p. 766.

25. Kolb, L.C., and Himmelsbach, C.K.: Clinical Studies of Drug Addiction. III. A Critical Review of the Withdrawal Treatments With Method of Evaluating Abstinence Syndromes.Public Health Reports, Suppl. 128. Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office,1938, p.ll.

26. Lambert, Alexander: Report of the Mayor's Committee on Drug Addiction to the Hon. Richard C. Patterson, Jr., Commissioner of Correction, New York City. American Journal of Psychiatry, 87:433-538, 1930.

27. Ibid., p.475.

28. Ibid., p.534.

29. Sioe, Kwa Tjoan, and Hong, Tan Kim: Opiumontwenningskuren met blaarserum. Geneeskundig Tijdschrift yon Nederland Indie, 71:138-151, 1931.

30. Kolb, L., and Himmelsbach, C., op. cit., pp.14-16.

31. Detrick, L.E., and Thienes, C.H.: Experimental, clinical and legal aspects of drug addiction. California and Western Medicine, 43:331-337, 1935.

32. Piker, Philip, and Gelperin, Jules: Death complicating the withdrawal of narcotics, with respiratory difficulties predominant: report of three cases.Annals of Internal Medicine, 10:1279-1282, 1937.

33. Piker, Philip: Insulin in treatment for symptoms caused by withdrawal of morphine and heroin: a report of ten cases.Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 36:162-169, 1936.

34. Kolb, L.C., and Himmelsbach, C.K.: 1938, op. cit., pp.13-14.

35. Wieder, Herbert: Objective evaluation of insulin therapy of the morphine abstinence syndrome. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 110:28-35, 1949.

36. Wolff, P.O.: 1945-1946, op. cit., p.518.

37. Kolb, L.C., and Himmelsbach, C.K.: 1938, op. cit., pp.7-8.

38. Ibid., pp.3,7.

39. 1bid., pp.7-8.

40. Swain, Jean M.: The central nervous system in morphinism.American Journal of Psychiatry, 102:378-384, 1945.

41. Isbell, Harris: In Beeson, Paul B., and McDermott, Walsh ( Eds. ) : CecilLoebTextbook of Medicine. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Co.,1963, p.1746.

42. Helpern, Milton: Personal communication, October 8, 1969.

43. Pfeffer, A.Z.: Psychosis during withdrawal of morphine.Archives o f Neurology and Psychiatry, 58:221-226, 1847.

44. Margolis, Jack: Codeine addiction with death possibly due to abrupt withdrawal. Journal ofthe American Geriatric Society, 15:951-953, 1967.

45. Abeles, Hans, and Laudeutscher, Irving: Acute abdominal disease during drug withdrawal.New York State Journal ofMedicine, 68:2087-2089, 1988.

46. Kolb, Lawrence C., and Ossenfort, W.F.: The treatment of drug addicts at the Lexington Hospital.Southern Medical Journal 31:914-922, 1938; V'ikler, Abraham: Treatment of drug addiction.New York Stare Journal of Medicine, 44:2124-2131, 1944; Blachly, Paul H.: Management of the opiate abstinence syndrome. American Journalof Psychiatry, 122:742-744, 1966.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|