Chapter 8 The Evolution of Concurrent Opiate and Sedative Addictions

| Books - Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in United States |

Drug Abuse

The Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in the United States

Chapter 8

The Evolution of Concurrent Opiate and Sedative Addictions

CARL D. CHAMBERS AND MARY MOLDESTAD

In1950 Isbell and his associates at the Addiction Research Center confirmed the addictive properties of the barbiturates during the course of chronic intoxication and emphasized the necessity for a separate and distinct withdrawal regimen.' These initial reports and additional studies by Essig and Ainslie at the Addictiou Research Center have served to alert clinicians to the dangers of overprescribing barbiturates and other sedative drugs.2 These same reports have provided the clinicians with diagnostic techniques for assessing abuse and have emphasized the physical danger of withdrawal from sedatives.

Although clinicians at the Lexington Hospital had previously alluded to increased incidence in concurrent opiate and sedative abuse 3 and had suggested that sedative abuse occurred more frequently among white. opiate addicts, no substantial time-related data had been available from which to describe the evolution of sedative abuse among opiate addicts in the United States. The purpose of this study was to document the evolution in recent decades of the incidence of sedative abuse among known opiate addicts and to establish the involvement of each sex and race cohort.

Research Design

The study was designed to test empirically four clinical impressions: the incidence of sedative abuse has increased among opiate addicts; the incidence of sedative addiction has increased among opiate addicts; the incidence of sedative addiction among sedative abusers has increased; and the incidence of sedative abuse and addiction is more frequently found in white than Negro opiate addicts.

To accomplish a statistical analysis of these hypotheses, four hundred opiate addict-patients were selected. One sample of one hundred subjects twenty-five in each of the four sex and race cohorts-was selected from patients in each cohort who were consecutively admitted to the Clinical Research Center for treatment of narcotic addiction during 1966. Additional matched samples were selected from 1957 and 1948 hospital admissions. The fourth and final matched sample of one hundred subjects was selected by finding the earliest year during which a known concurrent abuser was admitted for treatment. The earliest year was 1944, and the final groups of sex and race cohorts were selected from that year. Two additional criteria were imposed during the selecting process. All of the subjects selected had voluntarily admitted themselves into the hospital, and all had been residing in a U.S. Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA).

The first criterion was enforced to insure the validity of research findings through the availability of clinical confirmation of opiate and sedative addictions. Clinical confirmation would not be available for patients being admitted as prisoners, since they would ordinarily have undergone drug withdrawal prior to their arrival at the hospital. The second criterion was imposed in an attempt to avoid contamination when making racial comparisons. Earlier studies 4 had revealed that most Negroes admitted for addiction treatment were SMSA residents, and it was deemed advantageous to compare opiate addicts who had access to similar drug subcultures.

For the purpose of this study, sedatives were those as defined by Maurer and Vogel' as being addicting nonopiate sedatives, excluding marihuana, and by Essig g as those newer sedative drugs that cause states of intoxication and dependence of the barbiturate type.

All data were obtained through a search of each subject's clinical record. The incidence of sedative abuse was available as a part of the drug abuse history taken by a physician at the time of admission for treatment. Sedative addiction, however, was defined clinically. Regardless of the patient's statement that he was addicted and regardless of the admitting physician's diagnosis of addiction (or nonaddiction ), no subject was considered a sedative addict unless the clinical records documented a sedative withdrawal.

The Incidence of Sedative Abuse

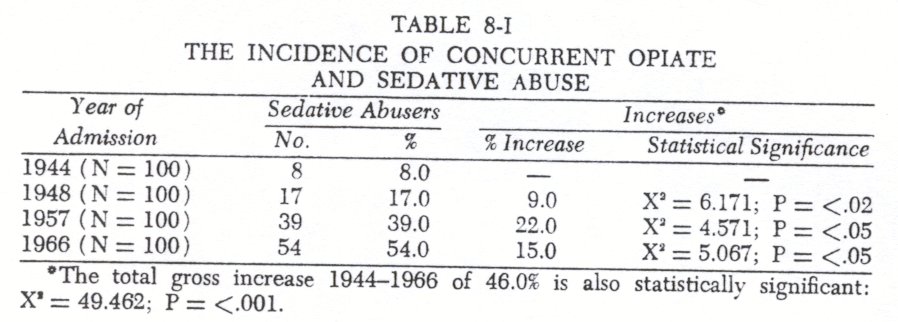

Comparing each of the admission year samples with the consecutive sample year, it was discovered that the incidence of sedative abuse had significantly increased between each time period since the first instances of concurrent abuse.

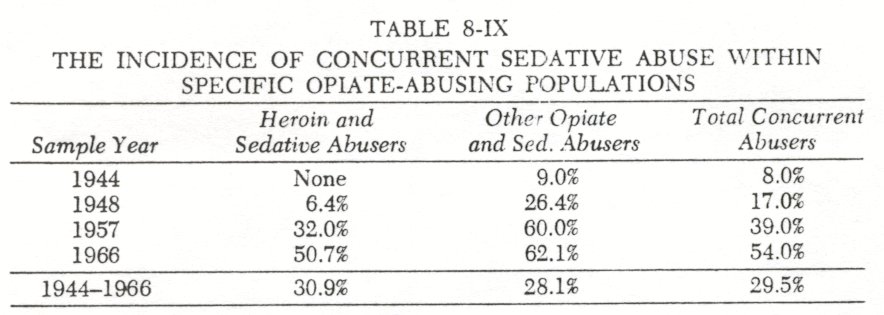

From an initial low of 8.0 percent concurrent abuse found among the 1944 addict-patients, the data indicate that by 1966 the incidence had increased to 54.0 percent. By 1966 concurrent sedative abuse had become a prevalent pattern among opiate addicts.

The Incidence of Sedative Addiction

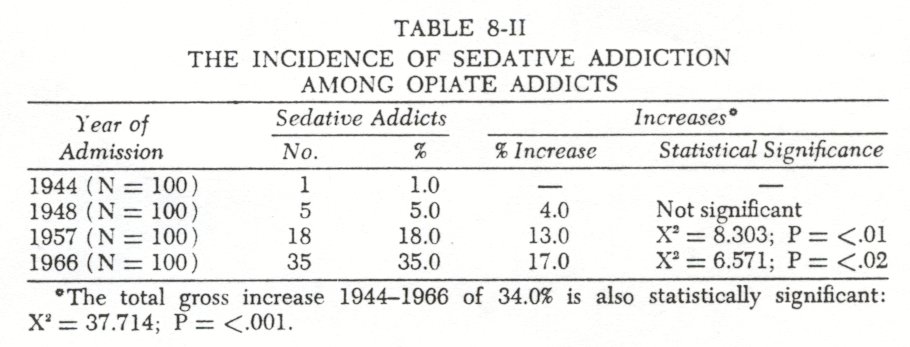

The evolution of the incidence of sedative addictions followed a somewhat different pattern. Significant increases between sample years did not occur as early as in the sedative abuse pattern.

From 1944 to 1948 the incidence of sedative addiction among opiate addicts was never over 5.0 percent. Between 1948 and 1957, however, the incidence increased significantly to 18.0 percent.

By 1966 35.0 percent o f all the opiate addicts were addicted to sedatives.

The Addiction Liability of Sedative Abuse

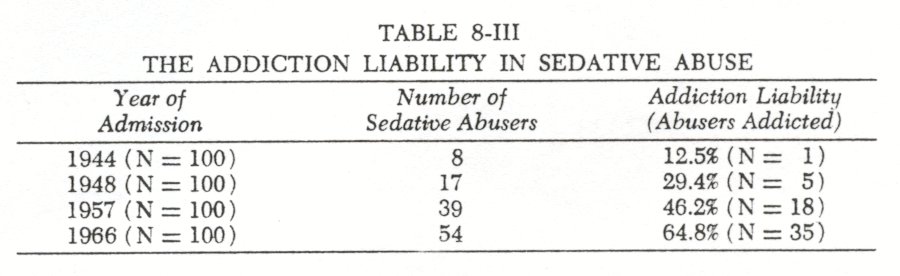

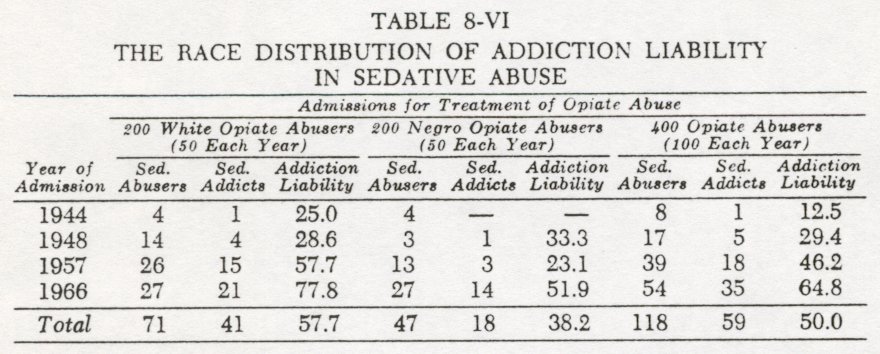

The addiction liability of a drug can be defined as the potential for addiction once an individual begins to abuse a drug. This liability could therefore be expressed as the percentage of individuals abusing a drug who became addicted to the drug. The data indicate that there has been a consistent increase in the addiction liability of sedative abuse for each time period.

The addiction liability of sedative abuse increased from the low of only 12.5 percent in 1944 to 64.8 percent in 1966. By 196664.8 percent of all the sedative abusers were found to be addicted to them. As measured by the distribution of those addicted and those not addicted among the sedative abusers, the increased liability was statistically significant.

The Race and Sex Cohorts

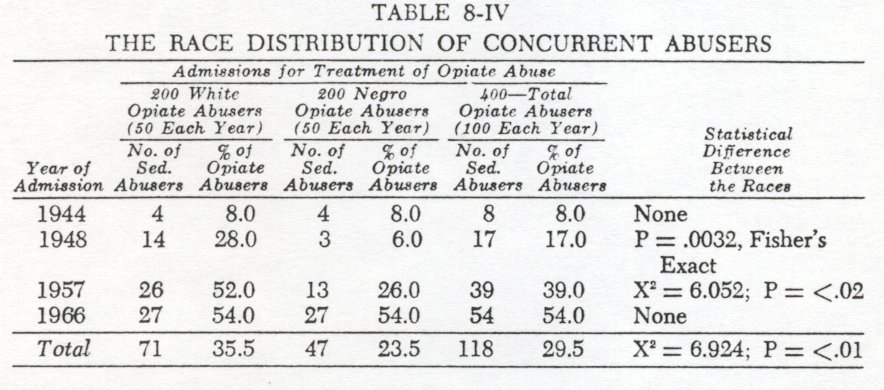

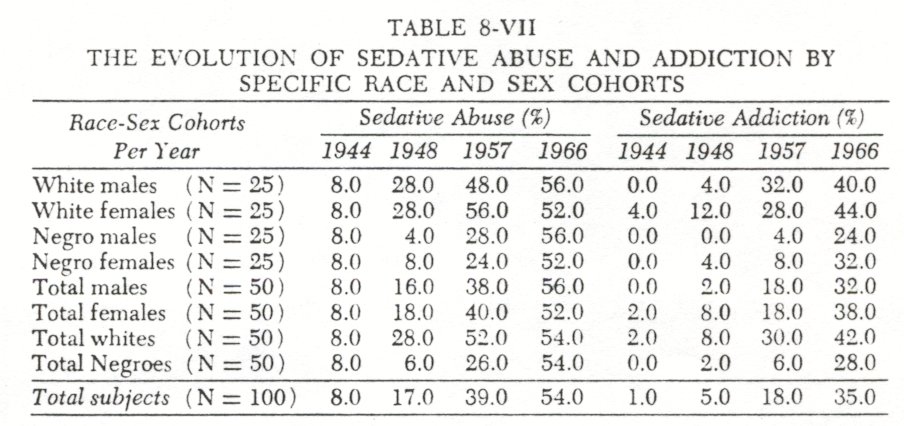

A between-races comparison revealed that sedative abusehistorically has been more frequently associated with the white opiate abusers. While 35.5 percent of all the white opiate abusers reported they also abused sedatives, only 23.5 percent of the Negroes were concurrent abusers. This difference, however, has undergone several significant evolutionary, changes.

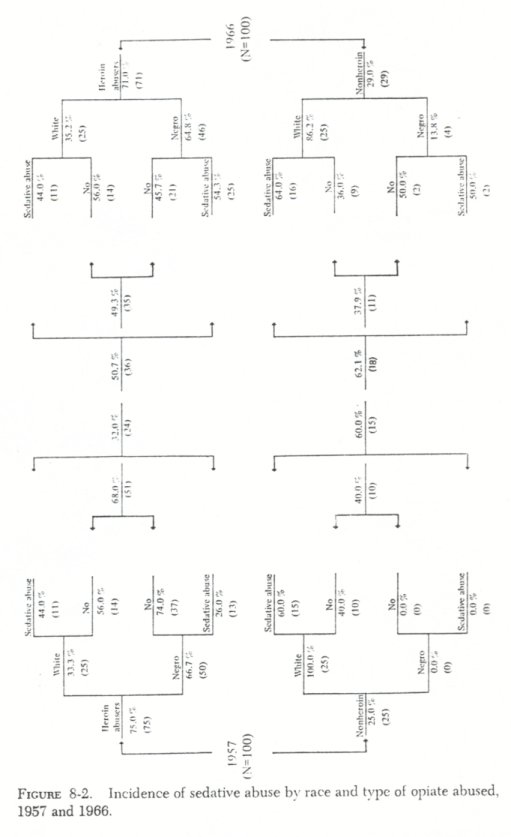

In 1944 concurrent opiate and sedative abuse was not associated with either race. By 1948, however, a race difference had emerged. Over one-fourth of the white opiate abusers were concurrently abusing sedatives, but only an insignificant number of Negro opiate abusers had adopted this new pattern of abuse. This race difference continued for at least another decade. By 1957 twice as many white as Negro opiate abusers were concurrent sedative abusers. By this time, however, concurrent abuse had become a significant pattern among Negroes, with over one-fourth of all Negro patients abusing both opiates and sedatives. By 1966 the race difference in the incidence of concurrent opiate and sedative abuse had disappeared, and concurrent abuse had become the prevalent pattern among opiate addicts o f both races.Thus, the Negro opiate abusers were approximately a decade behind the white abusers in adopting a pattern of concurrent abuse (1950's versus 1940's ) . The pattern diffused more rapidly among the Negroes, however, and by the mid-1960's, the racial differences had disappeared.

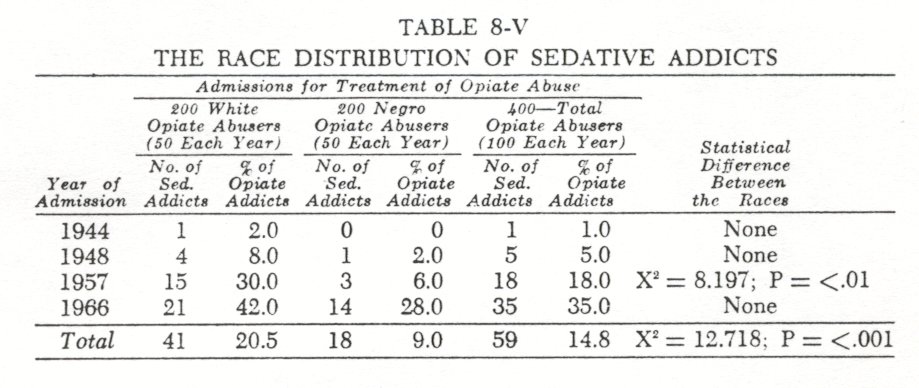

The incidence of sedative addiction within the two races followed much the same evolution ( Table 8-V ) . An analysis of the historical development of sedative addiction reveals that only 14.8 percent of all the opiate abusers were also sedative addicts. The white abusers, however, have contributed twice as many sedative addicts as have the Negroes. No significant racial differences in the increase of sedative addictions occurred until 1957. At that time, almost a third of all white opiate abusers were addicted to sedatives, while the incidence of this addiction was only 6.0 percent among Negro opiate abusers. While there were numerical increases in the incidence o_ sedative addiction for both races between 1957 and 1966, by 1966 the incidence of sedative addiction among Negro opiate abusers had increased sufficiently to eliminatethe statistical difference between the races. Again, the Negro opiate abusers were approximately a decade behind the white abusers in the acquisition of sedative addictions (1960's versus 1950's ) . By the mid-1960's the racial difference had disappeared.

Once racial differences in the evolution of sedative abuse and sedative addiction were noted, it became reasonable to hypothsize race differences in the evolution of addiction liability in sedative abuse.

A tabulation of the historical development of the addiction liability in sedative abuse indicated the high risk of addiction. Fifty percent o f all sedative abusers had become addicted to them. White sedative abusers had more frequently abused sedatives to the point of addiction than had the Negro sedative abusers. Although no significant race differences were evident during the earlier yearsof sedative abuse, between-race comparisons from1957 and1966 produced significant differences for both time periods. In1957, 57.7 percentof the white sedative abusers had become addicted; during the same period only 23.1 percent of the Negro sedative abusers became chronically intoxicated (P = <.04). The races remained significantly different through1966, with77.8 percent of the white abusers becoming addicted in contrast to51.9 percent of the comparable Negro group (P = <.05). A between-sex comparison revealed that there have been no significant differences between the sexes of either race in the incidence of either concurernt sedative abuse or addiction.

The Sedatives Abused

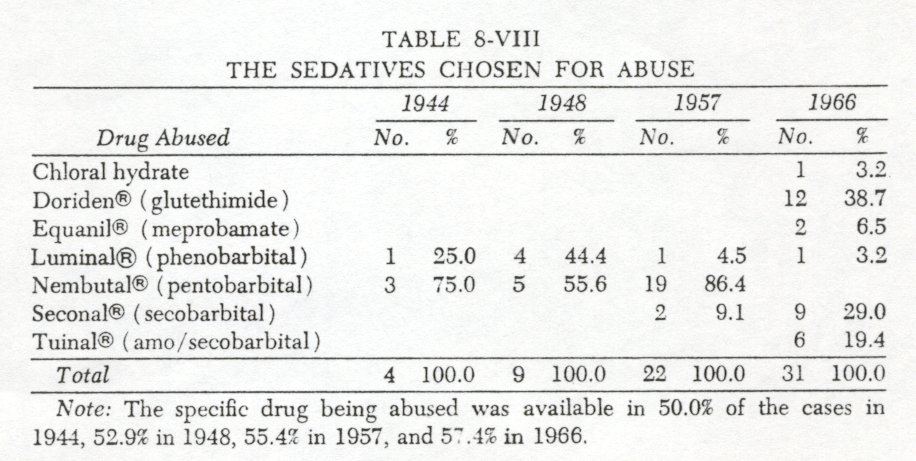

The clinical records usually identified the sedative being abused, although some abusers were unable or unwilling to specify the drugs. A comparison of the drugs specified indicated that a significant change over time had occurred in the drugs chosen for abuse.

Since the non-barbiturate sedatives, Equanil (meprobamate) and Doriden (glutethimide) were not developed until after 1950, the sedatives chosen for abuse during the two earlier years' samples could have included only the various barbiturates and chloral hydrate. Even after the newer sedatives (both of which were initially advertised as nonaddicting) became available, Nembutal was the sedative chosen for abuse. The discovery that 77.2 percent of all the sedative abusers during 1944, 1948, and 1957 had chosen to abuse Nembutal indicated their preference for a more potent short-acting barbiturate rather than the milder but long-acting drugs, e.g., phenobarbital and chloral hydrate.' By 1966, however, the abuse of Nembutal by the opiate abusers had complcteldisappeared. In 1966 the sedative most frequently chosen for abuse was Doriden (glutethimide).

It is also significant that by 1966 sedative abuse was no longer restricted to one or two sedatives. Abuse of six different drugs, twice as many as for any other year sampled, was reported. The finding that almost half of all the sedative abusers in 1968 were abusing nonbarbiturates is consistent with other research indicating heightened interest in nonbarbiturate sedatives among opiate addicts."

The Type of Opiate Abused and the Incidence ofSedative Abuse

In a further attempt at ascertaining what types of opiate abusers were most likely to be concurrent abusers of sedatives, the authors separated the addict-patients into two groups; one group consisted of those who had been heroin abusers and the other comprised of the abusers of the other opiates.

A percentage tabulation of the accumulated sedative abusers revealed that the two groups did not differ. Between 1944 and 1966 30.9 percent o f all the heroin addicts and 28.1 percent o f the other opiate addicts had concurrently abused sedatives. Stated somewhat differently, between 19-14 and 1966 the total opiate addict population studied was equally distributed between heroin addicts and abusers of other opiates (51.0 heroin and 49.0 other opiates). Within these two equally divided groups, the prevalence of concurrent sedative abuse was also equally distributed ( 30.9% of all heroin addicts and 28.1% of all the abusers of other opiates).

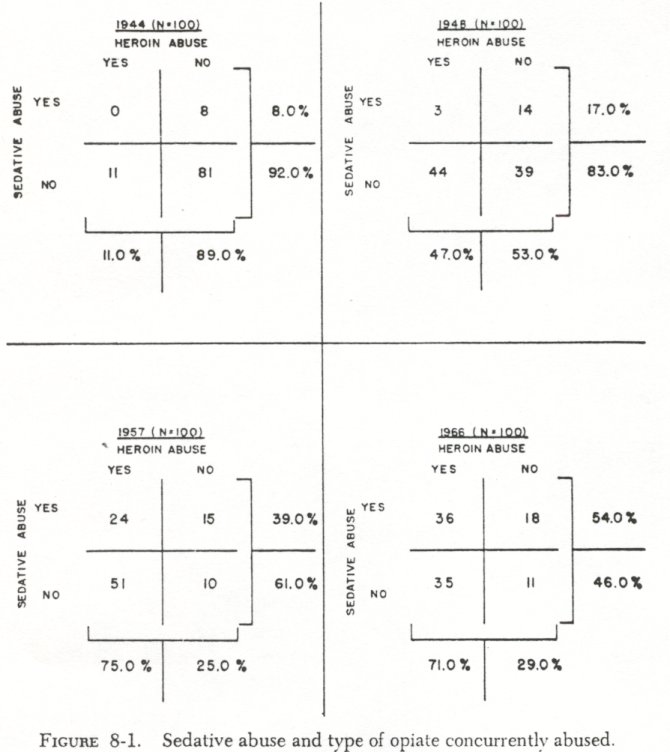

The evolutionary pattern of concurrent abuse was found, how ever, to differ significantly for these two groups. In each of the years sampled, the incidence of concurrent abuse was greater within the non-heroin group. During the first two onset periods, 1944 and 1948, 88.0 percent of all concurrent abusers were non heroin abusers. Although the incidence of concurrent abuse within the heroin group showed a gross increase of 26.0 percent between 1948 and 1957, the group remained significantly different from the non heroin group. In 1957 60.0 percent of the non heroin but only 32.0 percent of the heroin abusers were concurrently abusing sedatives ( X2 = 5 .058; P = < .O5 ) . By 1966, however, while the incidence of concurrent abuse among the non heroin abusers remained approximately the same (62.10, concurrent abuse among heroin abusers showed a statistically significant increase to 50.7 percent (Y= = 3.841; P = <.Ol). It becomes apparent, therefore,

that although the incidence of concurrent sedative abuse has remained higher among the non heroin abusers, the significant increase of incidence among heroin abusers had reduced the differences to the point that the type of opiate being abused is

no longer predictive of concurrent sedative abuse ( Fig. 8-1) .

Among contemporary opiate abusers, concurrent sedative abuse is the prevalent drug pattern regardless o f which opiates are being abused.This close association between the rise in incidence of sedative abuse among opiate abusers and the rise in incidence of heroin abuse among opiate abusers suggests that sedatives became readily available and acceptable in the illicit drug subculture in the late 1940's.

The evolutionary pattern of concurrent abuse as associated with the type of opiate abused was not independent of the previously described association with the race of the abuser. The sig-nificant increase noted in the latter years in the incidence of relative abuse was not evenly distributed throughout the heroin abusers-from 26.0% to 54.3% (fig. 8.2). The race difference by type of opiate abused remained the same between 1957 and 1966 (non heroin abusers being primarily white), but the race differences associated with sedative abuse disappeared because of negro increase in use.

Age and Concurrent Abuse

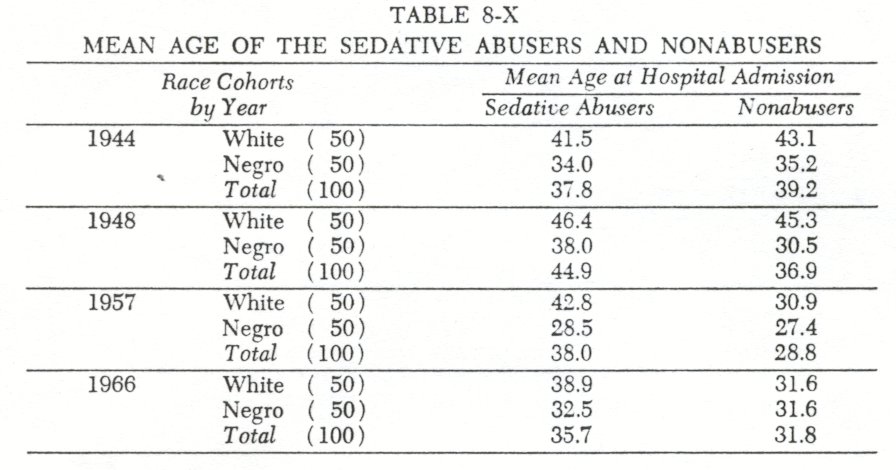

Mean age comparisons between concurrent abusers and those opiate abusers who did not abuse sedatives reveal additional evolutionary changes and race differences.

During the earliest year of concurrent abuse (1944) , the concurrent abusers of both races were younger than the opiate abusers who did not abuse sedatives (Table 8-X) . By 1948, however, the pattern was established that concurrent opiate and sedative abuse was associated with the older opiate abusers. This pattern has continued to the present.

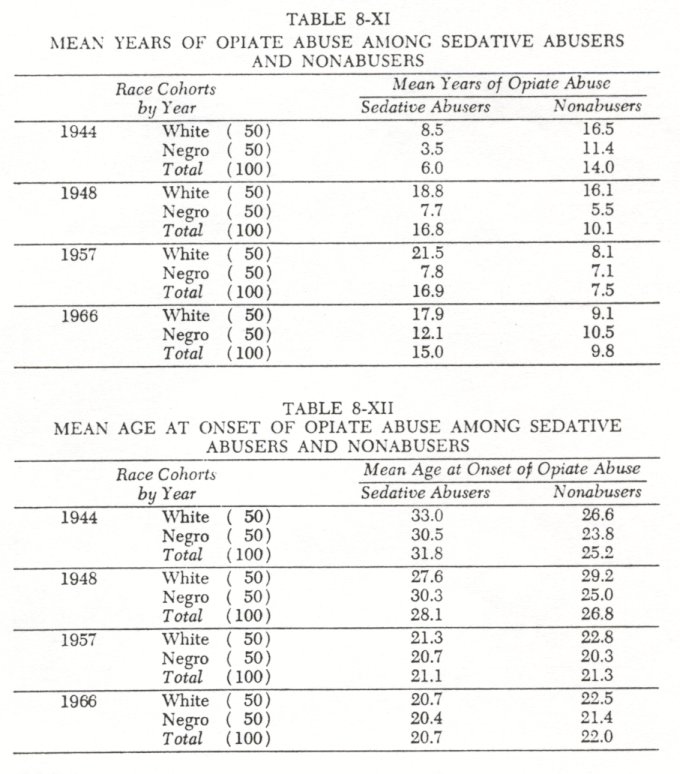

The data also indicate an association between the duration of opiate and concurrent sedative abuse (Table 8-XI). Excluding the earliest year (1944) , sedative abusers o f both races have longer histories of opiate abuse.

Thus, concurrent sedative abuse is associated with the older opiate abusers and with those persons who have beon abusing opiates for longer periods of time. Concurrent abuse, however, was not found to be consistently associated with the age at which opiate abuse began.

During the earlier years of concurrent abuse, the sedative abusers were more frequently found among those persons of both races who had begun their drug abuse later in life (Table8-XII). Any differences between the races and between the concurrent abusers and non abusers of both races have gradually diminished, and by 1957 they were no longer significant. At the present time the age at which an individual begins to abuse opiates is no longer predictive o f the concurrent abuse of sedatives.

Summary and Conclusions

Using only voluntary admissions to insure a clinical basis for the diagnosis of addiction and only SMSA residents to insure that all subjects would have had access to similar drug subcultures, one hundred opiate abusers consecutively admitted to the Lexington Hospital during 1966 were compared with three additional samples of subjects consecutively admitted during1957, 1948, and1944. Using these four hundred subjects, the study was designed to test four clinical impressions: that the incidence of concurrent sedative abuse has increased among opiate abusers; that the incidence of sedative addictions has increased among opiate abusers; that the addiction liability for sedative abuse has increased; and that the incidence of both concurrent sedative abuse and sedative addiction is more frequently found in white than in Negro opiate abusers.

Empirical support was found for the clinical impression of increased concurrent abuse. The incidence of concurrent sedative abuse among all opiate abusers increased from 8.0 percent in1944 to54.0 percent in1966. Concurrent abuse is now the prevalent pattern of abuse.

Empirical support was found for the clinical impression of increased sedative addiction. The incidence of sedative addiction among all opiate abusers increased from 1.0 percent in1944 to 35.0 percent in1966. At the present time over one-third of all the addicts seeking treatment for opiate addictions will also need concurrent treatment for a sedative addiction.

Empirical support was also found for the clinical impression of increased addiction liability. The addiction liability of sedative abuse was only 12.5 percent in1944, but by1966 64.8 percent of all the sedative abusers were found to be addicted to them.

The fourth clinical impression that sedative abuse and addiction were more frequently found among the white rather than Negro opiate abusers was found to have been true but was no longer so. Significant race differences in both the abuse of sedatives and addiction to sedatives had disappeared by1966. One significant race difference remains. White sedative abusers are more likely to become addicted to these drugs once they begin to abuse sedatives than are Negroes.

The increased incidence of abuse and addiction to the sedatives was shown to be primarily attributable to the disproportionate increase of such drug use among Negro heroin abusers.

Of significance to the clinicians who assume responsibility for the treatment of opiate abusers are the findings that concurrent sedative abuse will be a prevalent drug pattern in patients similar to those studied here. Furthermore, one of every three opiate abusing patients is likely to be addicted to sedatives, so that separate withdrawal regimens will be indicated. The finding that two of every three sedative abusers become addicted to them should serve to reinforce previous warnings against over-prescribing these drugs for self-administration even though the finding is based on opiate addicts, possibly a group especially liable to abuse other drugs.

Of special significance to the behavioral scientists is the documentation of an evolutionary pattern of drug abuse. The data suggest that sex differences have never been a significant factor in the abuse of or addiction to sedatives. Race does appear to have been a significant factor in the past, with Negroes lagging behind white narcotic users in adopting the use of sedative drugs. By 1966, however, this race difference had disappeared, and barbiturate-sedative use had become a prevalent pattern for both races. White abusers of sedatives are, however, still more likely to become addicted to the drugs than Negroes, once they begin using them. It is possible this difference is also related to time. In1966 the addiction liability among Negroes did not differ from that found among whites in1957.Since the racial differences in the incidence of barbiturate sedative used and addiction disappeared over time, it is reasonable to expect the racial differences in addiction liability would also decrease or disappear.

The apparent evolution in type of barbiturate-sedative abuse cannot be fully explained. There is some indication Doriden was chosen for abuse because of a mistaken belief it was less addicting than the barbiturates. There are cases, however, of abusers changing to Doriden because the effect was more satisfactory to them. Neither report has, however, been sufficiently documented.

The data suggest the hypothesis that, given continuity of the current circumstances surrounding opiate use, the incidence of sedative abuse and addiction among opiate users may not significantly increase beyond the 1966 level. The relative stability of the white pattern of abuse and addiction to these drugs since 1957 supports such a hypothesis. The homogenizing effect of the SMSA illicit drug subculture, wherein both races tend to prefer and use the same drugs, tend to purchase these drugs from the same illicit sources and tend to administer the drugs in the same manner and setting, would also support such a hypothesis.

1. Isbell, H.: Addiction to barbiturates and the barbiturate abstinence syndrome.Annals of Internal Medicine 33:108-121, 1950, and Isbell, H. et al.: ~ Chronic barbiturate intoxication: an experimental study. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 64:1-28, 1950.

2. Essig, C.: Addiction to nonbarbiturate sedative and tranquilizing drugs. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 5:334-343, 1964; Essig, C.: Newer sedative drugs that can cause states of intoxication and dependence of barbiturate type. journal of the American Medical Association, 196:714-717, 1966; and Essig, C., and Ainslie, J.: Addiction to meprobamate. journal of the American Medical Association, 164:1382, 1957.

3. Isbell, op. cit., Note 1. See also Hamburger, E.: Barbiturate use in Narcotic addicts. journal of the American Medical Association, 189:366-368, 1964.

4. See Chapter 5 and 7. See also Chambers, C., Moffett, A., and Jones, J.: Demographic factors associated with Negro opiate addiction. International journal of the Addictions, 3 (2):329-343, 1968.

5. Maurer, D., and Vogel, V.: Narcotics and Narcotic Addiction. Springfield, Charles C Thomas, 1967.

6. Essig, op. cit. Note 2, 1966.

7. This finding substantiates a hypothesis presented as early as 1950 by Isbell and Fraser. See Isbell, H., and Fraser, H.: Addiction to analgesics and barbiturates.journal o f Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 99 (4, Part 11): 355-397, 1950.

8. Laskowitz, D.: The phenomenology of Doriden ( glutethimide ) dependence among narcotic addicts. International journal of the Addictions, 2:39-52, 1967.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|