Chapter 15 Causes of Death Among Institutionalized Narcotic Addicts

| Books - Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in United States |

Drug Abuse

Chapter 15

Causes of Death Among Institutionalized Narcotic Addicts

JOSEPH D. SAPIRA, JOHN G BALK AND HARRY PENN

Note: Reprinted from theJournal of Chronic Diseases, 22:733-742, 1970.

It is recognized that narcotic addicts have a high mortality rate due to acute illness associated with drug abuse.' The use of adulterated drugs and communal syringes predisposes them to death from overdose, endocarditis, tetanus, hepatitis, and formerly, malaria. Less is known concerning the effect of chronic opiate abuse on mortality: Does the opiate addict die of ordinary causes after years of drug abuse or is he prone to specific diseases which lead to his early death?

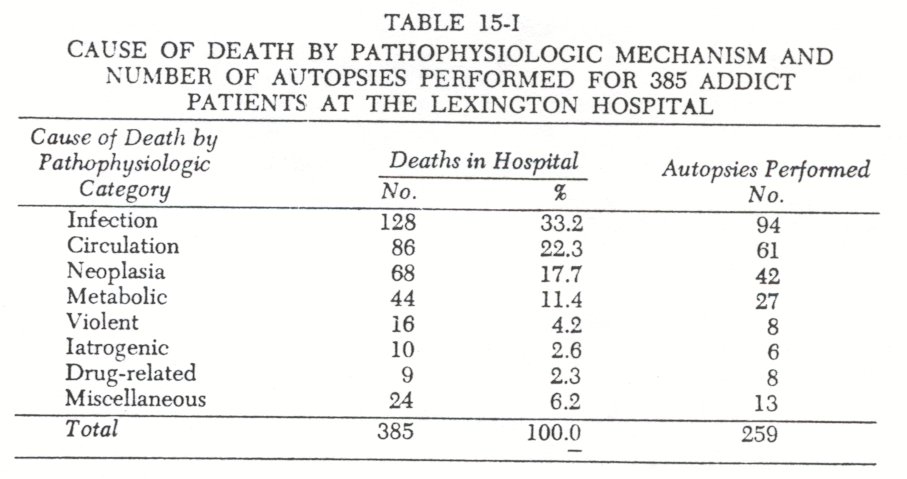

In order to investigate this question, a retrospective study was performed of all 385 deaths which occurred during hospitalization among the patients treated at the Lexington hospital since 1935. The patients in this study were admitted either because they volunteered for treatment or because then were serving federal prison sentences and were sent to Lexington for treatment and incarceration, pari passu. This study differs from previous research in several ways: ( a ) the population includes addicts from throughout the United States (it is not restrictedto a single city, state, or occupational group); ( b ) there is no selection by race, sex, or ethnic group, as admissions to the hospital over the past thirty-one years have reflected the demographic changes among addicts in general; ( c ) the sample is older than those of other studies, permitting analysis of causes of death following many years of drug use; ( d ) acute illness was not the principal reason for hospital admission ( the considerable distance to the hospital from the patients' state of residence was of significance in this regard); ( e ) the deaths usually occurred following a considerable period of institutionalization, with the result that antemortem clinical records were available.

Method

From May 29, 1935, to December 31, 1966, there were 385 deaths of addict patients at the Lexington hospital. Of the 34,043 male addicts hospitalized during this period, 348 died (1.02 ); the comparable figure for females was 37 deaths ( 0.40% of the 9,172 female addicts).

The cause of death was determined in each case by a detailed review of the clinical course record and, when available, the autopsy findings. An autopsy was performed for 67 percent of the deaths. The cause of death for each of the 385 patients was determined by two of the authors and a reliability check of this determination effected. This detailed review of the clinical records, autopsy findings, and collateral data was undertaken in order to employ a standard and reliable procedure for ascertaining the cause of hospital death.

Nonnatural deaths were defined as violent deaths ( due to suicide, homicide, or traumatic accident) or drug-related. There were twenty-five such nonnatural deaths. All other deaths(N=360 ) were considered natural, including those related to medical care which we have classified as iatrogenic. Of these,surgical deaths include only those deaths which occurred in the operative or immediate postoperative period ( i.e., within 48 hours), in which the surgery was elective and in which the death was not related directly to the object of surgery. Medical deaths include only deaths due to medical treatment or diagnostic procedures.

Results

Deaths are classified by pathophysiologic mechanism in Tables 15-I through 15-V. Many more male deaths occurred than female deaths, as would be expected from our predominantly male population. Since the female deaths did not appear to segregate among pathologic processes, they are not shown separately.

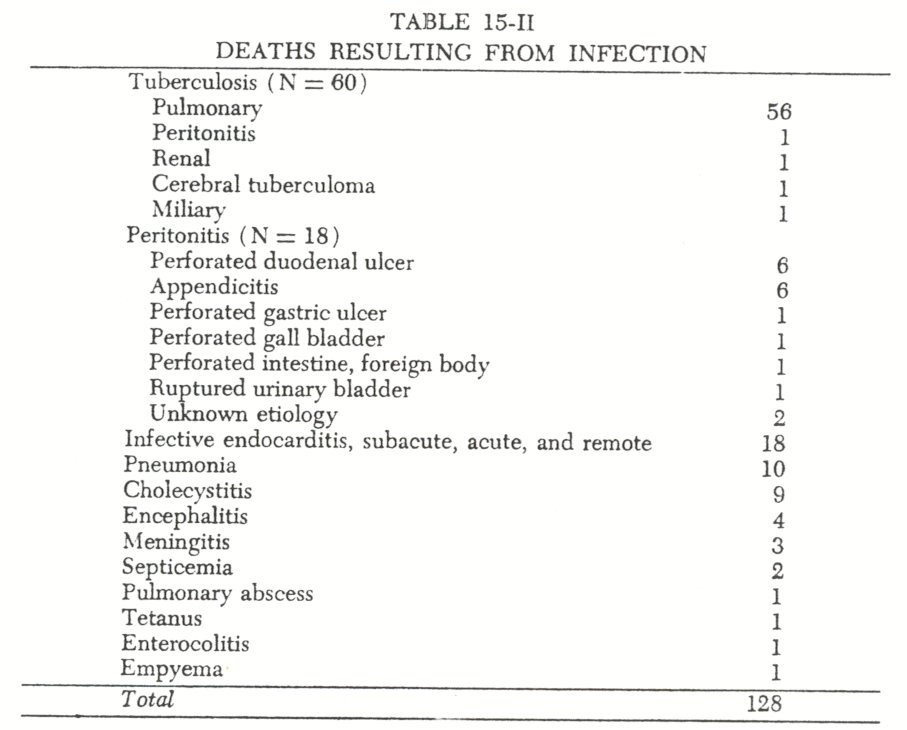

One-third (33.2%) of the deaths in this study were due to an infectious process. Of these, most were due to tuberculosis and bacterial endocarditiswhich are recognized concomitants of narcotic addiction. On the other hand, there were only two deaths from septicemia, one death from tetanus, and no deaths from malaria or acute viral hepatitis which are also considered to be diseases of addiction.

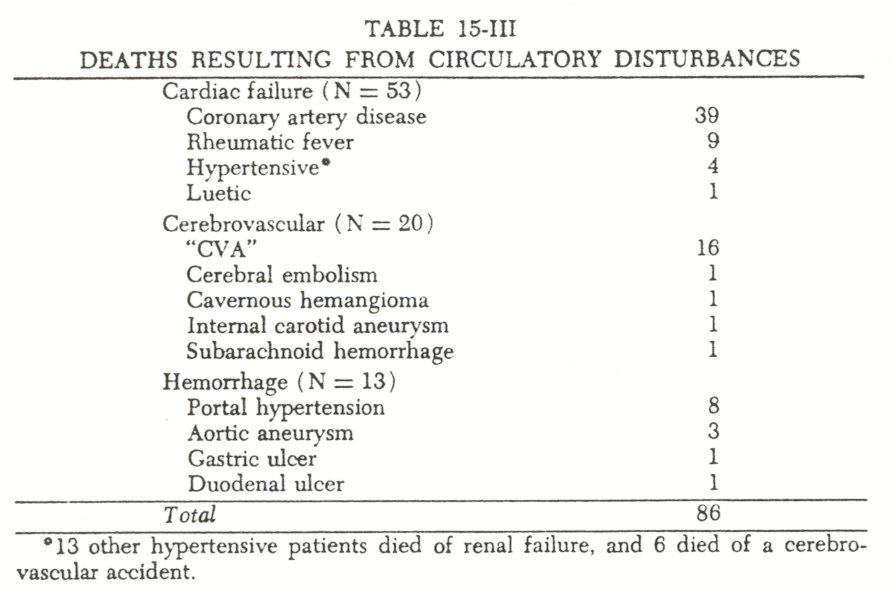

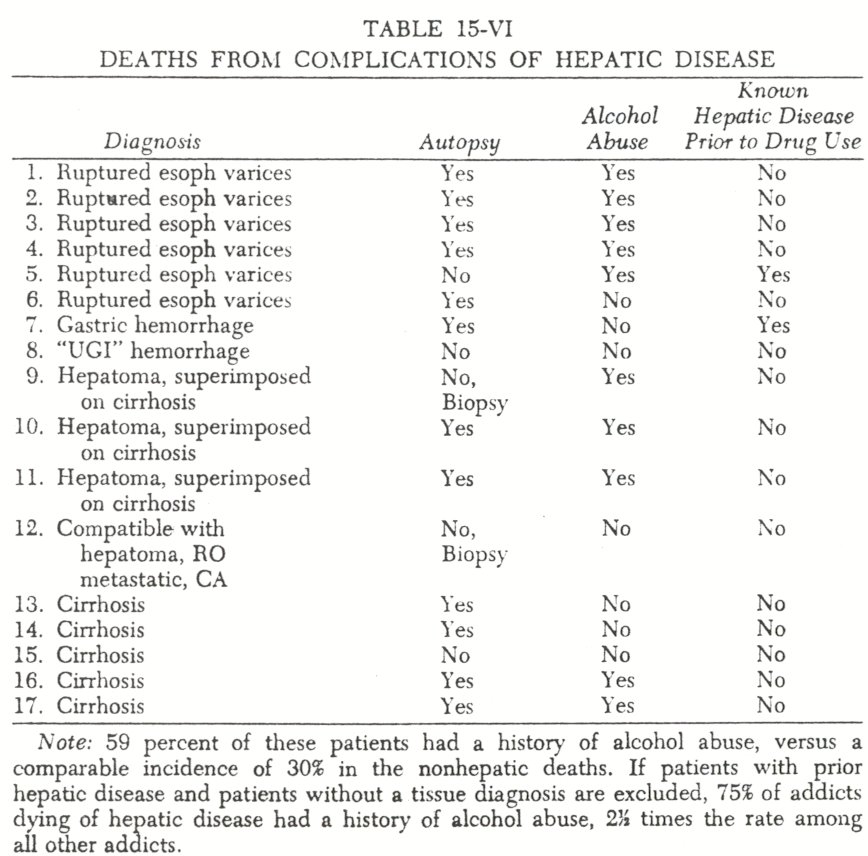

Over one-fifth (22.3%) died from a circulatory disturbance. Sixty-two percent of these died from cardiac failure. If the patients with complications of hypertension, cardiovascular collapse from septicemia, or bacterial endocarditis had been included in this group, both figures would be even higher. Eight deaths were attributed to bleeding secondary to hepatic portal hypertension. This was somewhat surprising, since recent studies of liver disease among narcotic addicts suggested that portal hypertension was not part of the clinical picture.2 In fact, we believe that evidence of portal hypertension in an addict should suggest a history of alcohol abuse ( or in the Puerto Rican patient, schistosomiasis ) . When these eight cases of hemorrhage secondary to hepatic portal hypertension were reexamined ( Table 15-VI), it was found that only one patient had autopsy-verified portal hypertension without evidence of either alcohol or hepatic disease predating addiction.

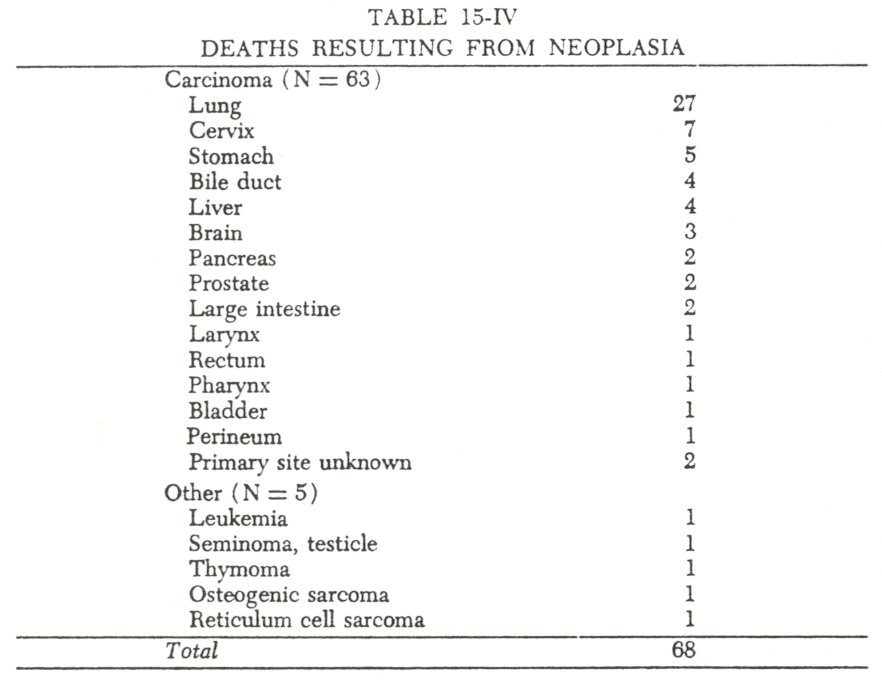

About one-sixth (17.7% ) of the deaths were due to a neoplastic process. As would be expected in a predominantly male population, carcinoma of the lung was the most common primary cancer. Four hepatomas were found ( Table 15-VI) but three of these were clearly complications of Laennec's cirrhosis due to alcohol abuse. The fourth was presumptively diagnosed as a hepatoma on the basis of an equivocal liver biopsy; unfortunately, this diagnosis was never confirmed or rejected.

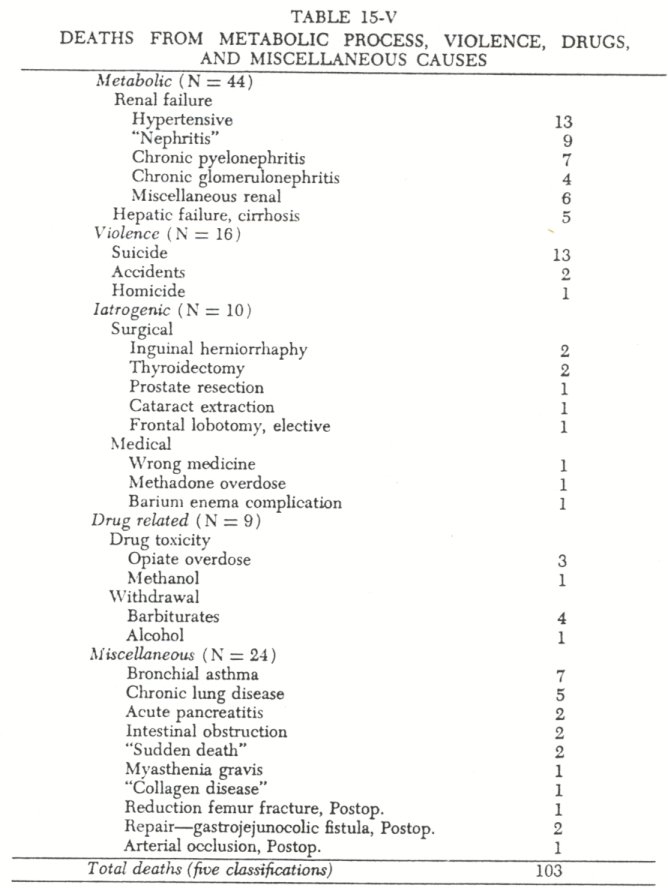

Forty-four patients (11.4% ) died a metabolic death. Of the four patients with hepatic failure who had a tissue diagnosis of Laennec's cirrhosis, two abused alcohol ( Table 15-VI.) The absence of diabetic ketoacidosis as a cause of death was consistent with our clinical impression -that diabetes mellitus is unusual in addicts and that .when it does occur, it tends to be quite benign.' The thirty-nine deaths from renal failure included thirteen listed asnephritis orchronic glomerulanephritis; most were autopsied, but the slides were not saved. It is of interest that there were no cases of diabetic glomerulosclerosis.

There were only teniatrogenic deaths. Of themedical drug deaths, one involved an overdose of methadone on the withdrawal unit, and one was due to the intravenous administration of magnesium sulfate instead of saline in the era when patients worked in the pharmacy.

In themiscellaneous group there were seven deaths from bronchial asthma, of which four were due to status asthmaticus. This is in keeping with our previous observation of a pulmonary allergic diathesis in the narcotic addict."

Violent deaths accounted for only 4.2 percent of the total.

This is much lower than in other reports,6 possibly because of the restrictive nature of institutionalization.

The death of nine patients was directly attributable to drug abuse. One patient died of delirium tremens the day of admittance ( in 1939 ) . Four patients died during withdrawal from barbiturates ( the first such death was in 1943, the last in 1960 ); these four deaths occurred from six to thirteen days after hospitalization. The four remaining drug-related deaths were caused by overdose. Two older patients ( 61 and 69 years) died within six hours of admittance from overdose of opiates. Finally, one patient died from an overdose of cleaning fluid, while another died from consumption of contraband codeine.

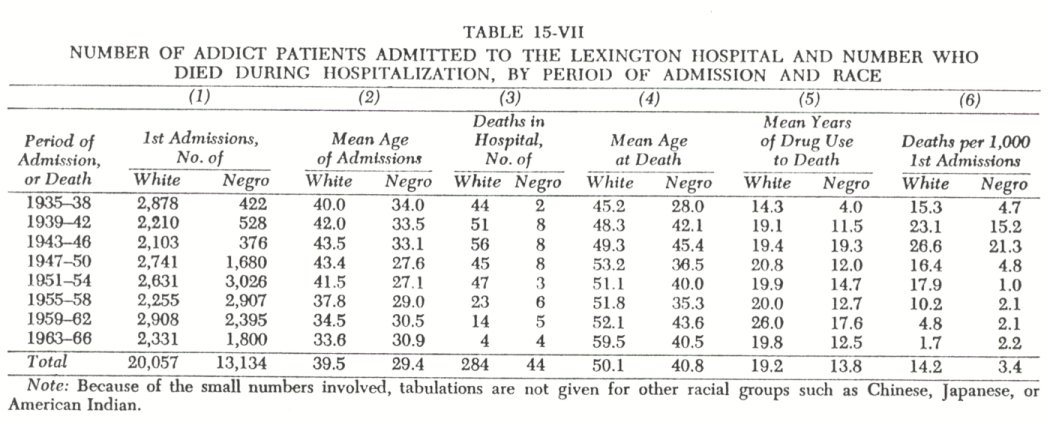

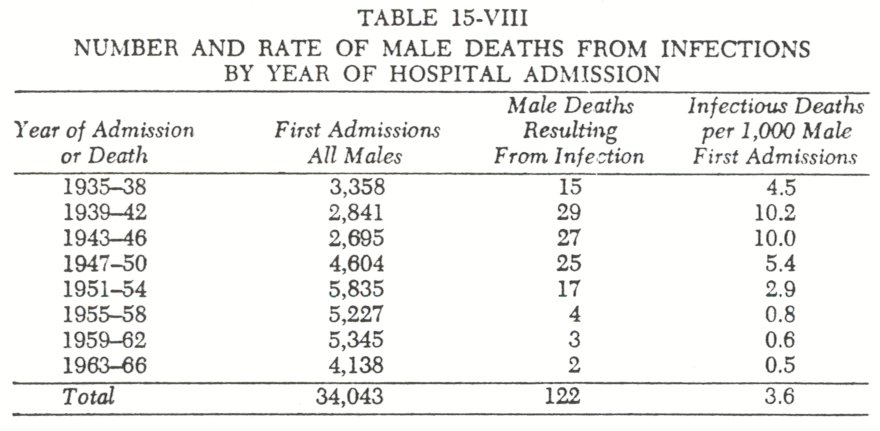

Both the demographic characteristics of the addict population and the cause of death among opiate addicts have changed during the period under study, 1935 to 1966. Table 15-VII shows mortality and demographic data from eight time periods. The first column indicates the increase of opiate addiction among Negroes following World War II. The second column depicts the younger age of Negro patients at hospital admission compared with white patients, although this age difference has decreased in recent years. Column three depicts the decline in deaths in recent years. The fourth and sixth columns show the consistently earlier age at death of the Negro patients and their lower death rate in all but the last time period. The principal reason for the mortality differences between the hospitalized Negro and white addicts appears to be the older age of the white patients. It is relevant to note that the Negro-white difference in observed death rates ( column 6, Table 15-VII) is not due to a longer history of addiction among the Negro patients, as they had fewer years of drug use than the white patients prior to death. Finally, the marked decrease of the death rate in recent years is considered to reflect both the younger age of the hospital population and general improvements in medical care. To study this last factor, we calculated the death rate due to infectiousprocesses for each period ( Table 15-VIII). It was found that the antibiotic era was followed by a notable decrease in deaths due to infection.

As mentioned previously, most reports on the cause of death among narcotic addicts are of necessity skewed toward those patients presenting themselves with acute illness. Most follow-up studies have been primarily concerned with the patient's addiction status following treatment, and causes of death are not broken down into disease categories. Two exceptions are the reports of Vaillante and O'Donnell.' Vaillant reported only twenty deaths, and the exact cause of death is not given in each instance. O'Donnell accepted the cause of death as that written on the death certificate. If the 385 cases in this study are reclassified according to the classification used for O'Donnell's 150 cases, we find that the leading causes of natural death in both series are almost the same: heart disease, neoplasia, tuberculosis, and central nervous system-vascular disease.

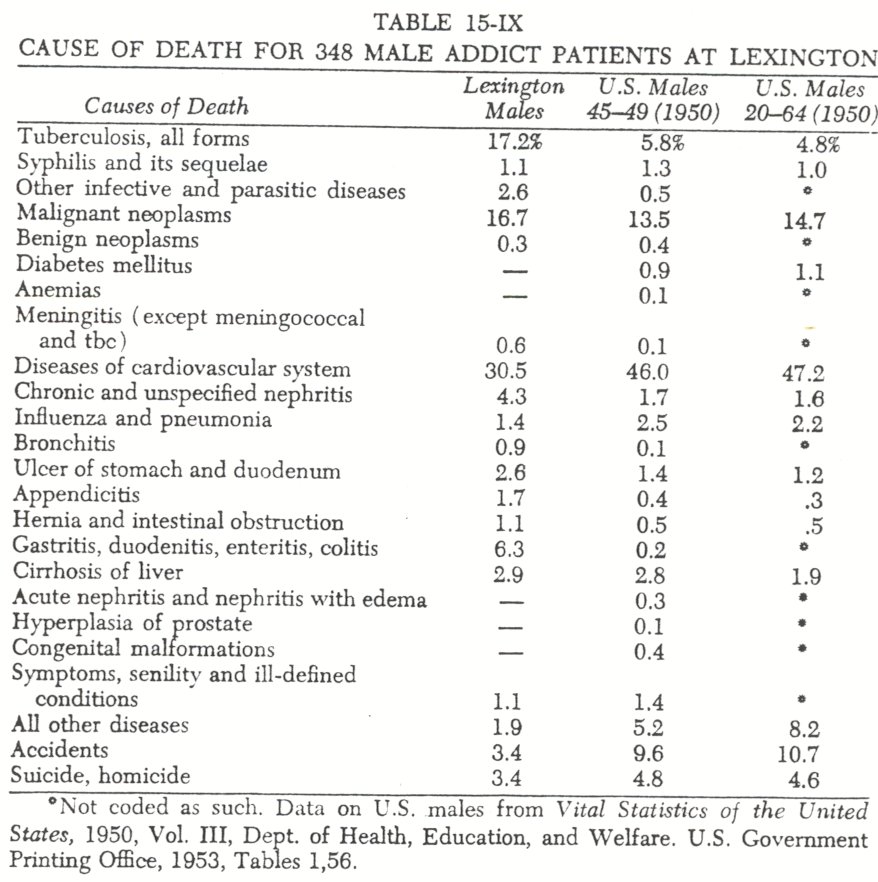

In order to compare the Lexington hospital deaths among addict patients with that of the U.S. population, the 348 male cases have been reclassified according to the categories used in the U.S. Vital Statistics ( Table 15-IX). Similarly, we havelisted the percentage distribution of deaths for all U.S. males between forty-five and forty-nine years of age ( the smallest interval including the mean age of death in the Lexington group) and between twenty and sixty-four years of age ( the largest interval). It is apparent that tuberculosis and nephritis were more frequent causes of addict deaths than would be expected if this were but a random sample of the U.S. male population.

It is likely that our population is skewed toward chronic illness in the same sense that earlier studies have been skewed toward acute illness. The exact incidences will probably be intermediate between the values in these two types of study, but their elucidation will require extensive posthospitalization follow-up of the type planned under the Narcotic Addict Rehabilitation Act.

Conclusion

A review of the causes of death among narcotic addicts during hospitalization at Lexington reveals a broader spectrum of disease than is apparent from similar studies originating from medical facilities concerned with acute illness.

Heart disease ( including infective endocarditis ), tuberculosis, and carcinoma of the lung accounted for over half of the deaths. On the other hand, tetanus, acute viral hepatitis, malaria, and opiate overdose, together accounted for less than 2 percent of the deaths.

1. Helpern, Milton, and Rho, Yong-Myun: Deaths from narcotism in New York City.New York State Journal of Medicine, 66:2391-2408, 1968; Siegel, Henry, Helpers, Milton, and Ehrenreich, Theodore: The diagnosis of death from

intravenous narcotics. Journalof Forensic Sciences, 11:1-16, 1986; Mason, Percy: Mortality among young narcotic addicts. Journal of the Mount Sinai Hospital, 34:4-10, 1967; Louria, Donald B., Hensle, Terry, and Rose, John: The major

medical complications of heroin addiction.Annals of Internal Medicine, 67:1-22, 1967; Cherubim Charles E.: The medical sequelae of narcotic addiction.Annals of Internal Medicine, 67:23-33, 1967.

2. Sapira, Joseph D.: The narcotic addict as a medical patient.American Journal of Medicine, 45:555-588, 1968; Sapira, Joseph D., Jasinski, Donald R., and Gorodetzky, Charles W.: Liver disease in narcotic addicts. II. The role of the needle.Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 9:725-739, 1988.

3. Ibid.

4. Sapira, Joseph D.:American Journal of Medicine. op. cit., pp.583-567.

5. O'Donnell, John A.: Narcotic Addicts in Kentucky. Washington, D.C., U.S.Government Printing Office, 1969, Ch. 2.

6. Vaillant, George E.: Twelve-year follow-up of New York Narcotic Addicts. II. The natural history of a chronic disease.New England Journal of Medicine, 275:1282-1288, 1966.

7. O'Donnell, J. A., op. cit.| < Prev | Next > |

|---|