Chapter 10 Onset of Marihuana and Heroin Use Among Puerto Rican Addicts

| Books - Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in United States |

Drug Abuse

The Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in the United States

Chapter 10

Onset of Marihuana and Heroin Use Among Puerto Rican Addicts

JOHN C. BALL

Note: Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Committee on Problems of Drug Dependence, National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council; Lexington, Kentucky-February 18, 1987.

I have often been asked how it was, and through what series of steps, that I became an opium-eater. Was it gradually, tentatively, mistrustingly, as one goes down a shelving beach into a deepening sea, and with a knowledge from the first of the dangers lying on that path; half-courting those dangers, in fact, whilst seeming to defy them? Or was it, secondly, in pure ignorance of such dangers; under the misleadings of mercenary fraud?

Thomas De Quincey, The Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, 1821.

From DeQuincey's time to the present there has been both literary and scientific interest in the onset of opiate use. The question of how and why a person starts the use of addicting drugs is one of pervasive significance, for it indicates the probable etiology and subsequent prognosis of the disease. In the case of heroin use the phenomenon of onset has particular contemporary relevance, as the illicit use of this drug has assumed noticeable proportions in the United States, Canada, England, and Hong Kong. Since its synthesis in Germany in 1898, heroin addiction has spread throughout much of the industrialized world; it has replaced opium and morphine as the preferred opiate among many confirmed addict populations. Both cultural and physiological factors are associated with the addicts' preference for heroin.'

In the present chapter the situational and personal factors associated with the onset of heroin use among Puerto Rican youth are delineated. Thetheatre of the event is considered: Who provides the illegal drug? How are techniques of administration learned? From whom? Where does the event occur? Are there precursors? How is opiate addiction spread among juveniles?

The Addict Sample

Between 1935 and 1962, 242 addict patients of Puerto Rican residence were discharged from the Lexington Hospital. A follow-up field study of these former patients was undertaken from 1962 to 1964 in Puerto Rico. The field experiences in Puerto Rico have been previously reported. 2

Clinical and administrative records from the Lexington Hospital provided case material on all 242 patients. These records included a psychiatric diagnosis, drug history and diagnosis, medical examination report, and other varied clinical and administrative data.

Post-hospital information was secured on 98 percent of the subjects; these data included local hospital and police records, personal interviews with addicts and their families, FBI records, and urine specimens. Of the 242 former addicts 122 were located and interviewed. The principal reasons for not locating subjects were death, migration from Puerto Rico, and incarceration in continental prisons. Of the 122 former Lexington patients interviewed, three were found to be marihuana users without a history of opiate addiction, either before or after their Lexington hospitalization. These three were excluded from the present study.

The interview schedule consisted of detailed questions pertaining to drug use, employment, criminality, and medical treatment. An analysis of the reliability and validity of the data obtained from the 132-hour interviews was undertaken; it was found that the responses were reliable and valid.' Inasmuch as a principal focus of the interview was to ascertain how the onset of opiate use occurred, research findings from the interviewed subjects were utilized in the present analysis.

Of the 119 opiate addicts, 107 were male and 12 female. At the time of interview the mean age of the males was 30.8 years and that of the females 36.2 years. With respect to preaddiction family background the 119 subjects were all of Puerto Rican ancestry, and most had been reared in families living in metropolitan areas of the island, especially in San Juan. Comparison with the 1960 census data reveals that the addicts came from families which were generally representative of the Puerto Rican population with respect to socioeconomic status.4 Thus, 10 percent of the fathers were in professional or managerial occupations, 44 percent were white-collar workers, 37 percent were skilled workers, and 10 percent were unskilled. The median years of schooling completed by the 107 male subjects was 10.0; the comparable schooling of the females was 9.0 years. Eleven of the subjects had attended or completed college.

Marihuana Smoking as a Precursor of Heroin Use

Heroin use among Puerto Rican subjects of this study began as a part of peer-group recreational or street activities. The juvenile initiate usually had smoked marihuana before his first experience with heroin, and in both instances he secured or was given the narcotic by neighborhood friends. The common sequence of events was commencement of marihuana smoking at age sixteen or seventeen, heroin use at eighteen, and arrest for possession or sale of drugs at age twenty. The onset of illicit drug use was, then, a peergroup phenomenon associated with delinquent behavior.

The mean age at which marihuana smoking began was 17.3 years for the males and 17.4 for the females. The youngest age at which marihuana use occurred was eleven years ( for two boys), and the oldest age was thirty. Although 15 of the 119 opiate addicts reported that they had never used marihuana, of those who had smoked marihuana 91 percent reported that marihuana use preceded opiate use. Thus, the dominant pattern of behavior was marihuana smoking followed by heroin use.

Inasmuch as the mere fact that one event preceded another does not indicate a causal relationship, it is pertinent to note that the friends and neighborhood circumstances associated with the first use of marihuana were similar to those found with respect to the onset of opiate use. Indeed, it sometimes happened that the same group of boys introduced the subject to both marihuana and heroin; twelve boys reported that the same group of friends introduced them to both marihuana and heroin.

Five reports of how marihuana smoking began suggest the importance of the peer-group:

(Case No. 80) The subject used marihuana for the first time when he was fourteen years old. In school there were a number of kids who smoked marihuana. One day while at recess one of his friends took out a cigarette ( marihuana ) and gave it to him to smoke. From then on he became one of the group. ( Year of onset: 1926. )

(Case No. 29) The subject began to use marihuana when he was sixteen years old. He was with four or five friends at this time. One of these, an older friend, was smoking marihuana and gave the group some. This older friend supplied the group for a while, then they had to pay for it. (Year of onset: 1934.)

(Case No. 166) The patient first used marihuana at age eighteen with a group of friends ( "boys with whom I grew up"). They were standing on a street corner where they used to hang around; . . . one of the oldest guys in the group had secured a number of marihuana cigarettes, and he distributed them among the group. They went on using marihuana for a whole year .... After one year they started to use Dilaudid. (Year of onset: 1946. )

(Case No. 147) The subject had his first experience with marihuana at age twenty-two while in New York City after his discharge from the army. He said he was living in a neighborhood where most of the kids were using marihuana; he was going around with this crowd until one night he decided to try it himself. They went up to one of the fellow's rooms and smoked marihuana. He went on using marihuana almost every day for a couple of months before he used heroin. He used heroin with the same crowd. He said that two of the fellows were heroin addicts, and they were also selling. ( Year of onset: 1954. )

(Case No. 211) The very first time he tried drugs, it was marihuana. It happened one night . . . . he was going with a couple of friends to a party. One of them got hold of some cigarettes, and they decided to try it. At first, he didn't get any "kicks" out of it, but the others seemed so excited, he decided to keep trying it. After that first night they would get together mostly on weekends and smoke marihuana. About three months later he tried heroin. ( Year of onset: 1958. )

The Onset of Heroin Use

Although marihuana smoking commonly preceded heroin addiction among the Puerto Rican youth of this study, this was not invariably the case. Thus, the question of how onset occurs among heroin users requires separate consideration. This is especially so, as the two substancesmarihuana and heroin-are not equally available, and the techniques of administration are different. In the latter regard, I refer to the fact that marihuana is smoked and heroin commonly injected. Thus, the use of heroin usually requires greater knowledge and a closer association with the drug subculture.

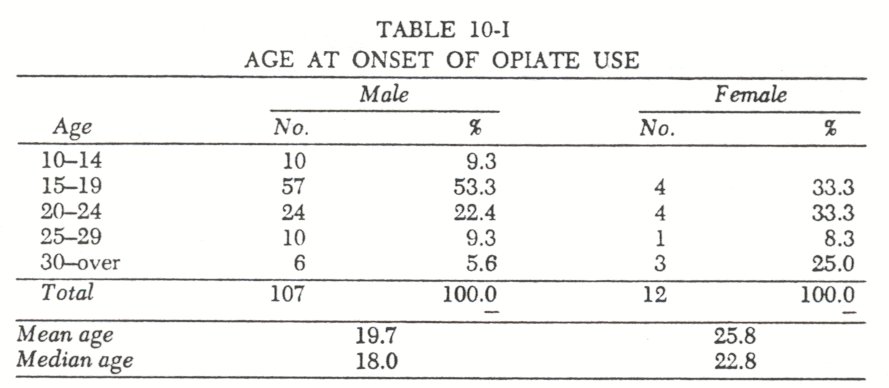

Of the 107 male addicts almost two-thirds had started use of opiates by age nineteen ( Table 10-I ) . The youngest age at onset was twelve years. After this first opiate use, addiction commonly followed within three months. Heroin was the predominant drug first used ( by 86% of the males), followed by morphine, Demerol, Dilaudid and opium.' As might be expected, the use of heroin as the initial opiate has become more prevalent in recent decades. Before 1950, 58 percent of the subjects started opiate use with heroin; in the 1950's this increased to 97 percent and by the 1960's it was 100 percent.

The two principal routes of administration employed at the time ,of first opiate use were intravenous injection and sniffing. Of the 107 males 39 started opiate use by intravenous injection, 39 by sniffing, 8 by subcutaneous or intramuscular injection, 9 by injection of unspecified type, and no data was available with respect to the first route used by 12 addicts. The intravenous . users were significantly younger at time of first opiate use than those who first employed other routes. The mean age at onset of opiate use for the thirty-nine intravenous users was 17.8 years, the comparable figure for the thirty-nine addicts who started by sniffing was 19.2 years, and for the remaining seventeen subjects the mean age at onset was 22.2 years. The difference in mean age between the intravenous users and those who first employed other routes was statistically significant (t= 2.01, P <.O5).

San Juan and New York were the two principal cities in which heroin use started. At the time of onset 66 percent were living in San Juan and 21 percent in New York City. The neighborhood locale of this first drug use was usually a street-corner hangout, friend's room, or an alley outside a party or dance. Thus, onset occurred in an unsupervised neighborhood setting in which the boys could pursue their clandestine activity of administering drugs with relative safety.

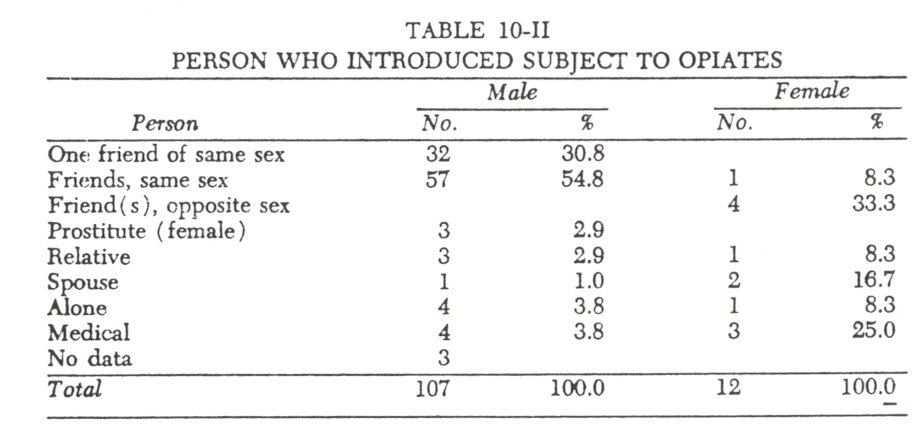

Perhaps most significant was the interpersonal situation in which heroin use started. Over four-fifths of the boys reported that they were initiated into drug use by friends who were addicts ( Table 10-II). Typically the neophyte asked his older neighborhood friends for a snort or shot and was given some heroin in return for delivering drugs to the group, or he was a part of a marihuana group when heroin was introduced as a new experience. The case material includes varied personal experiences with respect to onset, and several of these may not be without clinical significance. For example, Case No. 193 was given his first shot of heroin on a beach by a fifty-year-old man; Case No. 207 was started by a female prostitute. But these were atypical ( Table 10-II). The dominant pattern which led to the initial use of opiates was peeroriented status-seeking behavior. Some typical reports of how heroin use started were the following:

(Case No. 208) He was with a friend in a street alley. The friend was addicted and told him that he was going to meet with a group who used it ( heroin ) . He said that he would like to try it too. When the others were through, there was a little left, and he asked for it. They injected him.

(Case No. 209) The incident took place at a party with friends. Some of them were addicts, and some were not. His friends had the drug (heroin) with them. The subject wanted to use it out of curiosity. In order to use the drug the group went outside the party ( to the street). He used it intravenously this first time.

(Case No. 210) Patient was fourteen when he used heroin the first time. He was with friends in the street-they had bought the drug, and together they sniffed the drug on the street.

Delinquency and Drug Use

The onset of heroin use was preceded by marihuana smoking and followed by arrest. The male Puerto Rican addicts of this study smoked marihuana and associated with neighborhood boys who were known addicts before starting to use heroin themselves. The neighborhood addicts who provided the drugs and technical knowledge to the neophyte were invariably described by him as "friends." To the adults in the community, and particularly to the parents, these youthful addicts were considered a "fast crowd" and "bad boys." In this sense of differential association, it may be said that the boys had a delinquent orientation prior to the onset of opiate use.

With respect to arrests, 23 percent of the boys had one or more arrests prior to or, in one case, concomitant with the onset of opiate use. An additional 69 percent of the boys were first arrested after this event, and 7 percent had no arrest reported. There was, then, a marked sequence of events from drug use to official delinquency.

Onset of Opiate Use Among the Female Addicts

The onset of opiate use among the female Puerto Rican addicts was less closely associated with peer-group recreational activities and juvenile delinquency than among the male addicts. The females were significantly older at age of onset (22.8 years), less likely to have started opiate use in a street locale, more likely to have begun while in medical treatment, and less likely to have been initiated into drug use by addict friends of the same sex. Indeed, the females often began their use of opiates with one or more male addicts. In addition, and supporting the finding of less delinquent association among the females, was the fact that fewer used marihuana before starting on opiates, fewer used heroin when addicted, and fewer were arrested after the onset of opiate use.

Although the female sample is small and the findings should be cautiously regarded, there is reason to believe that onset among this group was less evidently a juvenile peer-group phenomenon. It appeared, rather, to be more closely related to personal inadequacies than to adolescent group experiences. The absence of comparable peer-group associations among females is tabulated in Table 10-II. In addition, the involvement in prostitution before the onset of drug use and the frequent rejection of the female addict by her parents and relatives suggest a different sequence of events and etiology from that found for the males.

Interpretation of Research Findings

The onset of heroin use among the Puerto Rican youth of this study is similar to the onset of juvenile delinquency in metropolitan areas of the United States. In both instances there is the dominant influence of deviant peer-group associations: commencement of either delinquency or opiate use usually involves the prior existence of a deviant group to which the initiate turns. Members of this deviant group are perceived as friends, and the deviant behavior is carried out in a neighborhood street setting. Of further interest is the fact that the addicts who initiated the subjects into opiate use were still regarded and described as friends. Thus, even after years of addiction and imprisonment, there was no later disposition to attribute blame or nefarious motives to those who had made onset possible.

To what extent the beginning opiate user or delinquent is aware of the dangers and probable consequences of his illicit acts is unknown. It seems likely that an overly rationalistic conception of the phenomenon of onset has been projected upon the young boy or girl. At fourteen or sixteen-or at college age is it realistic to expect that the efficacy of middle-class achievement norms will be recognized and the possible deleterious effects of alcohol, premarital sexual intercourse, cigarette smoking, stealing, or drug use known?

The onset of opiate use differs from the commencement of juvenile delinquency in several respects. The onset of drug use,

or that of marihuana smoking, is less overtly antisocial than most delinquency. The recreational or hedonistic situation in which drug use is started contrasts with the property offenses which characterize early delinquent behavior. In the former case the deviant behavior is within the group; in the latter it is directed toward outsiders. In addition, the two subcultures differ with regard to social structure and process. The addict group is not formally organized with designated roles and a leadership hierarchy as are conflict gangs; rather, one finds a more amorphous peer group association.

A more pervasive difference between the addict and delinquent groups is that the addict subculture is more enduring and less a transitory adolescent phenomenon. Most delinquent boys drift out of their gangs to assume adult roles as workers and fathers. Conversely, addicts become enmeshed in a way of life in which drugs, "hustling," and arrests are focal interests while steady work and family responsibility are neglected. Further, if the addicted state is continued into adulthood, the opiate user finds it difficult to establish, or reestablish, a legitimate social role in the community. In sum, the confirmed addict finds it more difficult to break from his deviant subculture than does the delinquent, and if he does so, it is at a later age.

Conclusion

The question of how opiate use started among the Puerto Rican addicts of this study has been answered. Heroin use started in an unsupervised street setting, while the subjects were still teenagers. The youthful initiate usually had smoked marihuana with neighborhood friends before using opiates. In the case of both marihuana smoking and heroin use, the adolescent peergroup exercised a dominant influence. The incipient druguser asked his older addict friends to be included in the group's primary activity.

As has been previously reported in the continental United States, there was no evidence that the onset of drug use among the Puerto Rican addicts was a consequence of proselyting, coercion, or seduction. Onset was, nonetheless, a group process.

The incipient addict willingly sought to join the addict group and learn the techniques and norms of the drug subculture. He was not in this process misled by "mercenary fraud."

Finally, it is pertinent to note that the interpersonal and situational factors associated with the onset of marihuana smoking and opiate use among the Puerto Rican addicts of this study have not changed during the past forty years. Although the incidence and prevalence of drug abuse in Puerto Rico may well have changed during this period, the evidence suggests that the peer-group behavior leading to the onset of drug addiction has remained unchanged.

1. In this regard see Wikler, Abraham: Opiate Addiction. Springfield, Charles C Thomas,- 1953, pp.55-57; Martin, W. R., and Fraser, H. F.: A comparative study of physiological and subjective effects of heroin and morphine administered intravenously in postaddicts.Journal o f Pharmacology and ExperimentalThera peutics, 133:388-399, 1961.

2. Ball, John C., and Pabon, Delta O.: Locating and interviewing narcotic addicts in Puerto Rico. Sociologyand Social Research, 49:401-411, 1985.

3. Ball, John C.: The reliability and validity of interview data obtained from59 narcotic drug addicts.American Journal of Sociology, 72:850-854, 1967.

4. U.S. Bureau of the Census:U.S. Census of Population: 1960. Detailed Characteristics. Puerto Rico. Final Report PC (1)-53D, Table 101. Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office,1982.

5. Of the 107 males 90 used heroin as their first opiate, 9 morphine 3 Demerol, 2 Dilaudid, 1 opium, and in two cases the opiate first used was unknown.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|