CHAPTER 4 GENERAL METHODS

| Books - Influence of Marijuana on Driving |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER 4 GENERAL METHODS

Before presenting the designs and results of the individual studies in separate chapters, it seems appropriate to describe the studies of the program and certain procedures that were common to all. In particular, compliance with ethical and legal standards, subject recruiting, marijuana cigarettes and smoking procedures, screening for the presence of other illicit drugs and alcohol, and blood sampling procedures and quantitative analyses will be elucidated.

4.1 Description of a 4-Study Program

The program was set up to determine the dose-response relationship between marijuana and objectively and subjectively measured aspects of real world driving; and, to determine whether it is possible to correlate driving performance impairment with plasma concentrations of the drug or a metabolite. These goals are the same as those of many unsuccessful investigations in the past. Yet none before has gone so far in seeking to achieve them in the environment where the 'drugs and driving' problem actually exists. In the present studies, a variety of driving tasks were employed, including: maintenance of a constant speed and lateral position during uninterrupted highway travel, following a leading car with varying speed on a highway, and city driving. The purpose of applying different tests was to determine whether similar changes in performance under the influence of THC occurs in all thereby indicating a general drug effect on driving safety.

The program consisted of one minor and three major studies; a series of separate but interdependent experiments that successively approached driving reality. This approach was necessary to ensure subject safety throughout the program. The program started with a laboratory study (Chapter 5), conducted in a hospital under strict medical supervision, to identify THC doses that recreational marijuana users were likely to consume before driving.

The first driving study (Chapter 6) was executed on a closed section of a public highway. The major goal was to determine the dose-response and dose-response-time relationship between marijuana (three different THC doses, and placebo) and road tracking precision as measured by the 'weaving' motion of the subject's vehicle during uninterrupted highway travel. Results of this are compared to those from a previous study undertaken by the investigators to measure the effects of different blood alcohol concentrations on driving performance in essentially the same test situation (Louwerens et al., 1987). A practical purpose was to determine whether the drug's effects as measured in a standard driving test were of a magnitude that would safely allow application of the same test and others on public roads in traffic.

Upon completion of this study with the demonstration that THC's effects could be safely controlled, a second driving study (Chapter 7) was conducted to come a step closer to driving reality than its predecessor. The methods applied were, with the addition of a car following test, the same as those used in the first driving study. However, driving tests were now conducted on a highway in the presence of other traffic. The greatest discretion was employed in designing this study to reach limited objectives. We choose a conservative approach which closely follows that used to determine the tolerability of medicinal drugs in human pharmacological research. It is to test THC's effects on actual driving performance in an ascending dose series. The ultimate goal was to define the THC dose (or plasma concentration) limit which separates low and high risk driving performance impairment by approaching it from the bottom up.

Yet normal driving is far more complex and varied than simply to maintain a safe lateral position and headway during uninterrupted travel on a highway. A THC dose having no effect on these parameters might still impair driving performance in more complex urban driving situations. For this reason the program then proceeded into the third and final driving study (Chapter 8) which involved tests conducted in high density urban traffic. The highest dose which had no significant effect on highway driving in the previous study was given to subjects who would now operate in an urban driving test. This provided an opportunity to measure a far broader range of driving performance. If no effect were again observed, the generality of the dose-effect relationship would be strengthened. But if a new kind of impairment were observed, the conclusion would have to be that the dose effect relationship can not be validly used to define the effects of THC on driving performance, in general. The nature of the new impairment would provide insight into the kinds of traffic safety problems that may be first to appear as a consequence of the drug's effects. A second group also participated in this study and undertook the same driving test, but then after drinking alcohol (reaching an average BAC of 0.04 g%), and a placebo. This was done for two reasons; first, the alcohol condition served as a control whether the employed tools to assess driving performance were sensitive; and, secondly, it made a comparison possible between low doses of alcohol and TI-IC.

4.2 Compliance with Ethical and Legal Standards

All studies described in this report complied with the code of ethics on human experimentation established by the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) as amended in Tokyo (1975), Venice (1983), and Hong Kong (1989). This implies that the volunteer subjects were fully informed of all procedures, possible adverse reactions to drug treatments, legal rights and responsibilities, expected benefits of a general scientific nature, and their right for voluntary termination without penalty or censure. All subjects gave their informed consent, in writing. Their anonymity was and will be maintained in all communications from the project. The investigators provided for continuous medical supervision and emergency medical treatment during the studies. Approvals for individual studies were separately obtained from the University's Medical Ethics Committee.

Before the program started an Independent Advisory Committee was formed whose function was to ensure that the program proceeded in accordance with all medical and legal standards. This committee comprised the Assistant District Attorney, the Municipal Traffic Attorney for the City of Maastricht, a member of the University's Medical Ethics Committee, and the Dutch Regional Inspector for Public Health (Drugs). A permit for obtaining, storing and administering marijuana was obtained from the Dutch Drug Enforcement Administration.

Subjects were accompanied on every driving test by a licensed driving instructor experienced in supervising subjects who operated under the influence of medicinal drugs in previous studies. The instructor's sole task was that of monitoring ride safety. Redundant control system in the test vehicle was available for controlling the car if emergency situations should arise. However, the primary guarantor of the subject's safety was the subject himself/herself. The subject, like any licensed Dutch driver, had the legal responsibility to stop driving when feeling 'under the influence' to the point where he/she could no longer be sure of his/her ability for safely controlling the vehicle. Subjects in this investigation were reminded of their responsibility and urged not to undertake any test, or to stop driving during a test in progress, if they felt incapable of driving safely. Subjects were always transported to and from their appointments and were strictly instructed not to operate their own vehicles for a period of 12 hours after having received the experimental treatment.

4.3 Subject Recruiting

The ideal subjects would be male and female marijuana users whose consumption of the drug represents that of the majority in that particular population. Van der Wal's (1985) data for the oldest group (17-18 years) in his sample of present Dutch cannabis users indicate that about 56% of the males and females have a usage frequency of more than once per month and less than daily. This usage frequency was considered as the first selection criterion.

The second criterion was that the users should also be experienced drivers in possession of a driver's licence. Subjects must have driven at least 5,000 km (3,108 mi) per year over the previous three years. This criterion was, however, not always met because of the difficulties in recruiting subjects.

As the third criterion the users should have indicated on a questionnaire that they had driven within one hour after smoking cannabis at least once within the preceding year. These users not only possess the requisite driving experience under the influence of marijuana, they also constitute the 'drivers at risk'. In addition, the application of this criterion avoided the ethical dilemma of requiring subjects to accept a risk which they would otherwise avoid.

As a fourth criterion, the subjects should agree to refrain from their normal marijuana use for at least five days prior to their participation in any test.

Other inclusion criteria were as follows: age 21-40 years; normal (corrected or uncorrected) binocular acuity (i.e. 20/25 Snellen acuity, or better); body weight within the 85th - 115th percentile range according to the 1983 table from the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company; and, Dutch nationality. The latter criterion was a condition set by the Dutch Ministry of Health which has no authority to permit the use of an illicit drug by foreign nationals.

Exclusion criteria included the following:

1. No history of treatment for drug or alcohol abuse or addiction and no reasonable possibility of dependence occurring as the result of participation in the investigation.

2. No record of arrests or conviction for drug trafficking.

3. No history of psychiatric or organic brain disorders.

4. No overt signs of cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, hepatic, metabolic or neuromuscular disorders and no history of serious disorders of this type.

5. No current use of any psychoactive medication (tranquilizers, antidepressants etc.)

6. For females, no pregnancy or any reasonable probability that pregnancy might occur during participation in the investigation.

Some subjects volunteered spontaneously after reading about the planned study in newspapers. Other volunteers for the first two studies were primarily obtained from among the local population of marijuana users by means of advertisements. Both the second and the third driving study required new samples of subjects. In these cases it was more difficult to recruit subjects since advertisements could not be placed where they might attract the attention of news media. The desire to avoid attention was fostered by a need to ensure subjects' anonymity and avoid the media's interference with data collection involving driving in traffic on public highways and city streets. Subjects were therefore recruited in the last two studies mainly by contacts obtained from subjects from the preceding ones. Admittedly this procedure is not the best to acquire independent samples but was necessary for practical reasons.

Volunteers were screened in two stages; first from their responses to a combined cannabis use, driving experience and medical history questionnaire; and secondly, on the basis of an interview and physical examination. Furthermore law enforcement authorities were contacted, with the volunteers' consent, to verify that they had no previous arrests or convictions for drug trafficking.

Subjects were instructed to sleep normally on the nights before test days. Alcohol consumption was prohibited for 24 hours before tests, and consumption of beverages containing caffeine, for 2 hours beforehand. Those who smoked tobacco were advised that this would also be prohibited for one hour before testing until its completion.

4.4 Marijuana Cigarettes and Smoking Procedures

Marijuana cigarettes were supplied by the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse. They were manufactured, dried, and analyzed for cannabinoid content at the U.S. Research Triangle Institute from Mexican marijuana grown by the University of Mississippi. Placebo cigarettes were prepared by ethanol extraction of cannabinoids from the plant stock. Cigarettes looked like standard tobacco cigarettes: they were approximately 85 mm in length x 25 mm in circumference and weighed an average of about 800 mg. Cigarettes were stored at -20° C and their moisture content was raised to about 16% for moderating their 'harshness' by humidification at room temperature over saturated sodium chloride solution in a closed container over the night before smoking.

Subjects smoked the administered cigarettes through a plastic holder in their customary fashion. In the laboratory study, they were allowed to smoke part or all of the THC content in three marijuana cigarettes, but with the constraint that smoking had to be finished within fifteen minutes. In the subsequent driving studies, cigarettes were cut to different lengths to provide the THC doses appropriate for the individuals' body weights, and subjects were encouraged to smoke the entire dose in five to ten minutes. The THC concentrations of the administered marijuana cigarettes varied between 1.75 and 3.58%, and are mentioned in the 'Methods' of the respective studies.

After cessation of smoking, cigarettes were carefully extinguished and retained for subsequent gravimetric estimation of THC consumed (i.e. the difference between the weight of the original cigarette and the remaining unsmoked portion times the THC proportion in the original cigarette). This method of estimating THC amounts consumed is based upon the assumption that THC is equally distributed over the entire cigarette. Perez-Reyes et al. (1982) analyzed THC concentrations in the unsmoked portions of marijuana cigarettes of three different potencies and indeed found that they were identical to those in the unlit cigarette.

4.5 Screening for the Presence of Other Illicit Drugs and Alcohol

Though it seemed unlikely that subjects would regularly resort to using other illicit drugs or alcohol prior to controlled marijuana smoking and testing, the possibility could not be definitely excluded without testing the subjects for the presence of these drugs. Therefore they were informed beforehand of the intention to obtain urine and breath samples which would be analyzed for the presence of prohibited agents.

Each subject was required to submit a urine sample immediately upon arrival at the test site. Samples were later assayed qualitatively for the following drugs (or metabolites): cannabinoids, benzodiazepines, opiates, cocaine, amphetamines and barbiturates. In addition a breath sample was analyzed on the spot for the presence of alcohol using a Lion S-D3 Breath-Alcohol Analyzer. The urine and breath sample screening procedures were employed in all studies in the program.

Drugs other than cannabinoids were found in urine of four subjects. In the laboratory study, the urine of two subjects was positive for benzodiazepines; and, of one subject for barbiturates. Analyses of six urine samples obtained from these subjects during the successive driving study failed to show the presence of these drugs. Since all urine samples from both the laboratory and first driving study were analyzed after completion of the latter, the failure to detect the drugs in samples obtained during the driving study indicates that they did not abuse these drugs. Upon questioning, all three subjects denied that they had taken these drugs. Since no urine or plasma was left from these subjects, it was, however, not possible to check whether the results were false positives. Data obtained from these subjects in the laboratory study were not excluded from the statistical analyses. One subject's urine, obtained prior to smoking in the 200 itg/kg condition in the first driving study, was positive for cocaine. Upon questioning, the subject replied that some friends had surreptitiously administered him cannabis cake and cocaine the day before. Assuming that the drugs' effects had dissipated the next day, these subject's data were also not excluded from statistical analyses.

4.6 Blood Sampling and Quantitative Analyses

Blood samples were taken by venepuncture. Two 10 ml aliquots were obtained in every case. These were heparinized and centrifuged within 30 minutes. Plasma was placed in frozen (-20°C) storage prior to analysis. The quantitative chemical analysis of THC and THC-COOH in plasma was performed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Gc/ms) using deuterated cannabinoids as internal standards (Moller et A, 1992). Of the many analytic techniques available at present, GC/MS is the reference method of choice (Cook, 1986). Applying this method, the detection limits for THC and THC-COOH were about 0.3 and 3.0 ng/ml, respectively. THC and THC-COOH concentrations in plasma will further be abbreviated to [nic] and [THc-cooH].

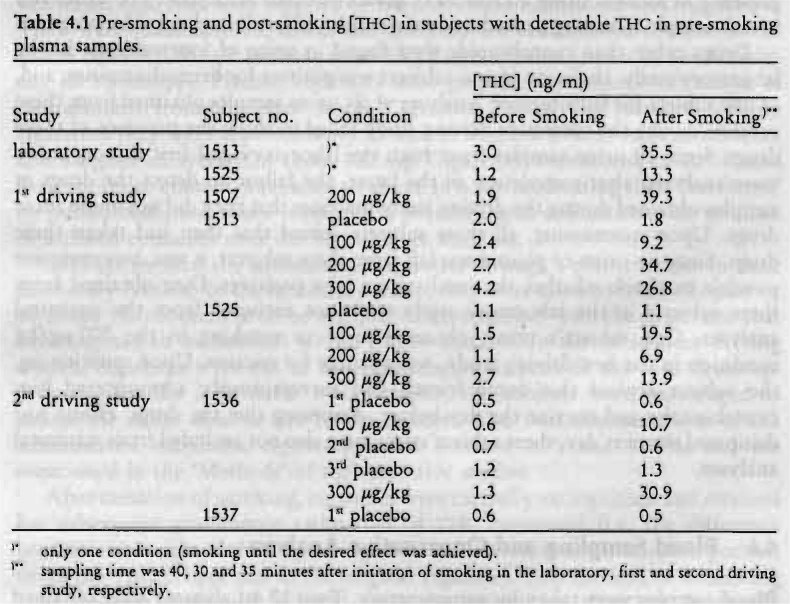

If the urine analysis (above) was positive for cannabinoids, plasma taken before smoking was also analyzed to quantitatively determine [nic] and [Thic-cooH]. Subjects with detectable THC in pre-smoking plasma are shown in Table 4.1. In the laboratory and first driving study, THC was detected in each pre-smoking plasma sample from two subjects and in one sample from another subject, namely prior to smoking in the 200 p.g/kg condition. In the second driving study, THC was detected in one sample from one male and in five out of six samples from another male. In the city driving study, THC was not detected in any pre-smoking sample.

It seems obvious that those subjects, who had detectable [Tic] before smoking, did not comply with the instruction to abstain from cannabis consumption for at least five days prior to the trial. They all had long histories (at least 7 years) of cannabis experience and were frequent (at least twice a week) users. Gieringer (1988) reports that THC may persist in the blood of chronic smokers at levels up to 4.0 ng/ml after 48 hours. It therefore remains an open question when their latest consumption was or whether they were impaired upon arrival at the laboratory.

The same pattern of pre- to post-smoking values as shown in Table 4.1 was observed in the other subjects, i.e. [THc] and [Ti-ic-cool-i] increased considerably after smoking the administered marijuana cigarettes and not following placebo. Therefore, these subjects' data were not excluded from the statistical analyses.

Fifty percent of the pre-smoking plasma samples obtained from subjects in the laboratory and first driving study, whose urine tests were negative for cannabinoids, were also analyzed. These analyses were performed to examine whether any false negative urine analyses had occurred. Results showed that none of these samples contained detectable [THc] or [Thc-coon From these results it was inferred that in subsequent studies pre-smoking blood samples need only be taken if the urine test for cannabinoids were positive.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|