Chapter 3 The Extent of Chronic Opiate Use in the United States Prior to 1921

| Books - Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in United States |

Drug Abuse

The Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in the United States

Chapter 3

The Extent of Chronic Opiate Use in the United States Prior to 1921

CHARLES E. TERRY AND MILDRED PELLENS

Note: Reprinted with permission of the American Social Health Association, fromThe Opium Problem. New York, Bureau of Social Hygiene, 1928, Chapter 1. A new title and section headings have been added and some of the text deleted, otherwise there were no changes made in the original chapter. The entire volume has been reprinted by Patterson Smith Company, Montclair, New Jersey, 1970.

The number of individuals involved is probably what first brings any problem to the attention of the public. It bears a definite relationship to control, and if it is demonstrated that a problem is confined neither to a community nor to a section of the country, neither to one social group nor even to one race, but is widespread and common to all, such facts should be used as the basis for eliciting interest, for pointing out the need for remedial measures, and for framing such measures. Likewise, the converse is true. A knowledge, therefore, of the extent of the problem with which we are concerned is a matter of importance and should receive early consideration.

The attempts which we have made to secure an accurate estimate of the number of chronic opium users in the United States at the present time emphasize an unusual situation. We find estimates varying all the way from a few thousand individuals to several millions. One states that 100 thousand to 200 thousand is the outside limit, while another states that 2 million or more is a conservative figure. The lay press, popular magazines, and even scientific journals vary so widely in their estimates of the number of sufferers from this condition that one is justified in accepting none of them unreservedly and in analyzing afresh allavailable means for the determination of the actual facts.

It will be seen not only that no one is possessed of an accurate knowledge as to the exact number of individuals regularly using opium in this country today but also that under present conditions it is impossible to obtain such a figure. There are several reasons why this is true. In the first place, the fact that opium using in any form is regarded by the general public as alone a habit, vice, sign of weak will, or dissipation undoubtedly has caused the majority of users to conceal their condition. This attitude presumably attributes to the individual either a physical or mental inferiority, the concealment of which is quite natural. This factor applied before the problem ever became a matter for official and legislative action and undoubtedly- became intensified when it was taken up officially and the individuals desirous of solving it made their views the basis of propaganda for control. With the advent of prohibitory legislation and the consequent fear of legal involvement, it is natural that even greater efforts were made by individuals affected to conceal their condition.

Quite aside from this individual point of view is the fact that only in cases where large doses of the drug are being consumed can casual observation or even a fairly careful examination determine the existence of the condition. There is a popular belief extant that practically anyone can detect the so-called dopefiend, that he is a miserable, emaciated, furtive individual with pinpoint pupils, trembling hands, sallow complexion, and characterized by a varied group of moral attributes, needing only to be observed to render identification of the condition complete. As a matter of fact, not even one of these alleged characteristics need be present, and it is safe to say that in many cases only one or another of them exists and by no means would suffice to give the ordinary observer an idea of the true situation. It has been reported that for many years husbands and wives, to say nothing of other members of a family, have lived in complete ignorance of the existence of this condition in one or the other and that quite possibly the average physician, unaccustomed to dealing with the condition, might have difficulty in determining its existence.

In view of what has been said, it would seem quite evident that there is no accurate knowledge as to the exact number of chronic opium users in the country today, as it is apparent that if the condition is considered a physical, mental, or moral stigma and if it is possible to conceal it from any but the most scrutinizing examination, unknown cases inevitably must exist. This may be expected to continue as long as the present attitude toward the user of these drugs exists with the social and economic damage resulting from exposure, and the illicit traffic offers a means of supply. That the illicit traffic exists to a very marked degree, we know; to suppose that the dangers of disclosure are not appreciated by individual sufferers would be to consider them lacking in ordinary intelligence. However, in spite of the obvious difficulties in the way of an accurate determination of the number of cases of chronic opium intoxication, startling statements constantly are being made.

Further, so far as we know, there has been made no study of a sufficiently large and representative number of individual cases under suitable conditions to permit of any definite statement as to an average daily dose. For instance, it is well known that certain cases continue for years on one or two grains or even a fraction of a grain daily, while others take such almost unbelievable doses as eighty to one hundred or more grains a day. Also, among a certain type, the amount stated as habitually consumed by an individual may include the ration of one or more other individuals unknown to the investigator.

As far as we know then, there are two obstacles to the determination through importation figures of a minimal figure for the number of chronic opium users in this country at the present time: (a) the fact that the so-calledlegitimate therapeutic needs are unknown and (b) the wholly speculative nature of theaverage dose. In view of these facts, all estimates as to the extent of this condition based on importation figures however used are potentially fallacious to such a great degree as to be practically valueless.

The second method of determination is the employment of some means for the taking of a census of opium users in a given locality and adjusting it to the population of the country as a whole. Aside from the fact that it would not include those users who, by reason of their desire for concealment and consequent dependence on illicit traffic for supply, could not be recorded,' such a survey undoubtedly would possess a value not found in estimates based on importation figures in an attempt to reach a minimal figure, inasmuch as it would be definite and positive as far as it went. Of course, there is possibility of error to a greater or less degree in this method. The floating population, for example, cannot be disregarded; yet, this is a source of error common to every method of census taking. Further, local conditions such as population composition, climate, race distribution, occupation, and so forth, are influencing factors which tend to lessen the value of the individual surveys as applied to the country as a whole. Unfortunately, there have not been enough of these surveys made in various sections to determine by comparison the degree to which these factors operate. In what follows, the surveys which we have reviewed and which represent investigations made in different localities at different periods will be analyzed, and the features which tend to vitiate their application to the country as a whole, for the period in which they were made, will be pointed out.

Personal Accounts of Opium Use Prior to 1878

Before examining the first definite figures of which we have knowledge, contained in a survey reported by O. Marshall in the Annual Report of the Michigan State Department of Health of 1878, it will be interesting to quote from some of the earliest authors who refer to the extent of chronic opium intoxication in this country. Their statements, however inexact, at least show that the problem is by no means one of recent development but the result, as we know it today, of a continuous growth, probably since Colonial days. What effect the war of the American Revolution and that of 1812 had upon its spread, we have not seen indicated in any record we have consulted, but that the CivilWar gave it a considerable impetus seems definitely established.

Fitzhugh Ludlow-1867

The habit is gaining fearful ground among our professional men, the operatives in our mills, our weary serving women, our fagged clerks, our former liquor drunkards, our very day laborers, who a generation ago took gin. All our classes from the highest to the lowest are yearly increasing their consumption of the drug.2

Horace Day-1868

The number of confirmed opium-eaters in the United States is large, not less, judging from the testimony of druggists in all parts of the country as well as from other sources, than eighty to one hundred thousand . . . The events of the last few years (Civil War) have unquestionably added greatly to their number. Maimed and shattered survivors from a hundred battlefields, diseased and disabled soldiers released from hostile prisons, anguished and hopeless wives and mothers, made so by the slaughter of those who were dearest to them, have found, many of them, temporary relief from their sufferings in opium.3

Alonzo Calkins-1871 4

Calkins calls attention to the increased use of opium in this country from the year 1840. Independent and collateral evidences, he believes, show that "opium-mania, far from being restricted . . , to our cities . . . is fast pervading the country-populations." In the evidence he presents, he quotes the following:

Thus addresses the writer, a physician and druggist of a New England city, Dr. S. S.: "In this town I began business twenty years since. The population then at ten thousand has increased only inconsiderably, but my sales have advanced from fifty pounds of opium the first year to three hundred pounds now; and of laudanum four times upon what was formerly required. About fifty regular purchasers come to my shop, and as many more, perhaps, are divided among the other three apothecaries in the place. Some country dealers also have their quotas of dependents." Such is no solitary record.

In the Portland Press, 1868, a correspondent sounds the alarm note in these words: "Very few of our people are aware how many habitual consumers of opium among us a careful scrutiny woulddisclose. In the little village of Auburn (of the neighborhood) at least fifty such (as counted up by a resident apothecary) regularly purchase their supplies hereabouts; and the country grocers, too, not a few of them, find occasion for keeping themselves supplied with a stock." Corroborative accounts come in from New Jersey and Indiana, from Boston at one extreme and from St. Louis at another, and from the impoverished South as well. In the Mississippi Valley particularly, the use of stimuli of every name is fearfully on the increase (Pitcher, Comstock).

F. E. Oliver-1871

In the third Annual Report of the State Board of Health, Massachusetts, for the year 1871, there appears a chapter on the use and abuse of opium written by this author. The writer addressed the following questions to the physicians of Massachusetts:

-

1. Are preparations of opium used by the people except for the relief of pain?

2. We would like to know whether the injurious use of opium has increased of late years, and if so, the causes of such increase?

Unfortunately, these questions were not so framed as to elicit the information which the author desired to obtain, and as he himself states, the data secured are most incomplete although suggestive. Less than one-half of the physicians addressed were heard from, representing a little more than one-third of the pbvsicians of the state. In all, 125 physicians replied, 40 of these stating in answer to the first question that they knew of no case of opium eating. The remaining 85 stated that the drug was used to a greater or less extent in their respective circuits. In many of the smaller towns where the habit existed, the number of users was reported where it could be ascertained, while in the returns from others such terms as few, many, and several alone were given. In others again no mention was made of numbers, so that the author was not able to arrive at anything like an accurate computation. From the fragmentary data so obtained, the author states that the inference is unavoidable that the opiumhabit is more or less prevalent in many parts of the state, and while it is impossible to estimate it, the ~number of users must be very considerable.

The writer further gives the following extract from a letter received from Mr. S. Dana Hates, one of the State Assayers:

"In reply to your inquiries, it is my opinion that the consumption of opium in Massachusetts and New England is increasing more rapidly in proportion than the population. There are so many channels through which the drug may be brought into the State, that I suppose it would be almost impossible to determine how much foreign opium is used here; but it may easily be shown that the home production increases every year. Opium has been recently made from white poppies, cultivated for the purpose, in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Connecticut, the annual production being estimated b3· hundreds of pounds, and this has generally been absorbed in the communities where it is made. It has also been brought here from Florida and Louisiana, while comparatively large quantities are regularly sent east from California and Arizona, where its cultivation is becoming an important branch of industry, ten acres of poppies being said to yield, in Arizona, twelve hundred pounds of opium."

"That which is not used where it is produced, including the shipments from California and the West, together with inferior and damaged parcels of foreign opium received and condemned at this port, is sent, to Philadelphia, where it is converted into morphia and its salts, and is thus distributed through the country. 5

In his letter Hayes comments further on the use of opium and morphine in family remedies such as cough mixtures and liniments and in the dangerous so-called "cures" or "Relief for Opium-Eaters" preparations.

Oliver also quotes extracts from letters replying to his question as to the increase in the use of opium, some of which are reproduced below: g

" ... I think it on the increase because doctors prescribe it more indiscriminately now than formerly, thus establishing the habit with the patient."

" ... I think the use of opium has slightly increased, mostly among females."

". . . I have reason to believe this practice exceedingly common among certain classes of people, who crave the effect of a stimulant but will not risk their reputation for temperance by taking alcoholicbeverages."

". . . I have talked with some of our most intelligent apothecaries, who tell me the use of opium has greatly increased, especially among women. The reasons which one gave are these: The doctors are prescribing it more to their patients, and thus the habit is acquired. There is also the desire for some form of stimulant. Alcoholic stimulants being prohibited, many have resorted to the use of opium."

". . . I believe there is a natural craving for some artificial stimulant with almost every human being, which is greatly increased by the cares and perplexities of life, and therefore is more apparent as age advances."

". . . I think opium and its preparation are used to a considerable extent as stimulants and am inclined to the opinion that such use is increasing and that such increase is due, in some degree, to the excitements, suffering, and mental disquietude resulting from the late war."

Among twenty or thirty druggists consulted, there was a diversity of opinion, many of them not selling opium without a physician's order. The following statements are among the most important:

. . . Believes the habit of opium eating diminishing, as he has fewer calls than formerly .

. . . Has observed that veteran soldiers who contracted the habit in army hospitals are still addicted to opium .

. . . In the experience of twenty-five years has observed no decided increase in the habit of opium eating. Recognizes the correlation. in the abuse of opium and of alcohol. The opium habit frequently begins in the use o f opium medicinally. Veteran soldiers as a class are addicted to it . . .

. . . Would look for it rather among professional men than among the poorer classes .

. . . From his own experiences, believes that the habit of opium eating has increased within the last flue years from 50 to 75 percent.Never sells the drug without physician's prescription but has on an average five or six daily applications for some one of its preparations. It is largely taken by prostitutes .

. . . Has but one customer and that a noted temperance lecturer.

S. F. McFarland-1877

If cases of opium inebriety occur as frequently in the private practice of other physicians as they have in my own, it is coming to be a serious matter, and a few words of caution, against the indiscriminate use of so active a drug, may be pardonable.

Since the introduction of the hypodermic syringe, especially, there has been a noticeable increase in the frequency, as well as the severity, of these cases; and I wish to enter a protest against its imprudent use and particularly against leaving it in the hands of patients or their friends to be used at their discretion or even allowing them to know that they can use it, except in the greatest emergencies; for once in their possession and used for any considerable length of time, they will seldom discontinue it and will soon be inquiring where they can get "one of those things." It is certainly a most valuable instrument in the hands of the discreet practitioner and will reach cases which nothing else will with a certainty and promptness which is very satisfactory, but it is too potent for evil, as well, to be trusted beyond his grasp.

By the hypodermic use of opium the habit is much more rapidly produced than by taking it into the stomach, or by any other method-a fact which should not be lost sight of.7

Seven Studies of Opium Use From 1877 to 1920

Michigan Survey, 1877-0. Marshall 8

Turning to a consideration of the early surveys, the one already mentioned by O. Marshall deserves first consideration, as it was the earliest of which we have knowledge. While these figures are obviously quite incomplete, they represent at least a minimal extent and apparently can be depended upon as comprising positive information as far as they go. For these reasons they are of great importance to us today in seeking to arrive at a true conception, first, of the probable influence of factors other than illicit traffic and second, of their possible relationship to conditions of today.

Marshall begins his report with the following paragraph:

At a meeting of the State Board of Health in January, 1877, by a written communication, I called its attention to the large number of opium-eaters in the vicinity of North Lansing, giving many particularsrelating to the opium habit as it exists here. In complying with the request of the Board to prepare an article for publication, I have extended the investigation to other parts of the state, the result of which investigation is here given.

From further observations the author realizes how impossible it is to obtain complete and perfectly reliable information concerning this condition. He states:

Those best acquainted with its extent are the physician and druggist. As a rule, the physician, although originally responsible for many of the cases in his vicinity, is only aware of them through his business relation with the druggist. The latter, from whom the drug is obtained, from the fear of loss of trade, or, as some of them term it, a violation of confidential business, are often unwilling to furnish any information with regard to it.

Marshall sent two-hundred circulars to prominent physicians throughout the state asking for information in regard to the opiumhabit in their localities and enclosing a postal card with printed form for report of the number of men and women using opium and morphine in each place. Marshall took care to eliminate duplication of cases by addressing only one physician in each locality, and where reports from a physician included figures from two or more druggists, the lists were compared and repeaters eliminated. To those, ninety-six replies were received, giving the number of morphine and opium users in ninety-six cities, villages, and townships of the state. He says in this connection: "From the supposed impossibility of getting reliable information of the numbers in the larger cities, no circulars were sent to Detroit, Grand Rapids, or East Saginaw; and probably from this cause no answers were received from many of the larger cities of the state where circulars were sent."

The majority of the reports received by him include only those persons with whom the physician personally was acquainted. This, he points out, resulted in obtaining less complete information than had the druggists themselves been addressed. This, he says, is noticeable in the reports from two neighboring cities, one of which gives the large number of 116, which number was obtained after considerable effort by particular request, while the other reports only one case. A druggist, however, formerly in business in the latter city, estimated the number of opium users in that city at not less than sixty. From such facts as these Marshall comes to the conclusion that only the minimal number was obtained and that the actual number was probably greater in many instances. It is significant that throughout his whole report no mention is made of illicit traffic or an), source of supply other than that through physician and druggist.

Marshall summarizes his findings as follows:

The total number of opium eaters reported in the places given is 1313; of these, 803 are females and 510 are males . . . . The population of the cities and villages including the townships in which they are situated, according to the state census of 1874, was 225,633. The population of the whole state at the same time was 1,334,031. If the number of opium eaters including morphine eaters, in proportion to the population in the places given holds good for the entire state, the total number of opium eaters, all classes, in the state would be 7,763. Taking every degree of the habit into consideration, this estimate of the number is probably not too large.

If we find that Marshall's figures were based on representative, conditions common to all sections of the state, it is reasonable to assume that they may be applied also to the country as a whole. We may not assume, for instance, that the distribution of painful disease, of insomnia, of nervousness, or even of certain social proclivities and curiosity was peculiar to Michigan and that in 1877, through some mischance, its people, more than those of other states, were subjected to pernicious influences of this nature. Nor may we assume that the practice of medicine was conducted along widely different lines.in Michigan from those elsewhere or that the druggists of Michigan were more careless in the conduct of their business, less prone to make a profitable sale, or more blind to the harm resulting from this traffic than those of other states. In other words, there would seem no valid reason for not applying to the country as a whole such figures as Marshall gives us in depicting the extent of chronic opium intoxication in his state. Also, the resulting estimate for the country would be a minimal figure not only because of the incompleteness of Marshall's returns but also because of the absence in Michigan of certain influences which would tend to increase the use of opium .... On the west coast there were such influences as the maritime traffic with the Orient and the coolie labor imported for railroad and other construction undertakings, while in New England we have already seen poppy culture already was being indulged in, and shipments were being made to other states.

As a preliminary to the application of Marshall's figures to the State of Michigan as a whole, three things must be borne in mind-first, the total omission of returns from the larger cities; second, the fact which he himself brings out that information secured from the stated source, namely physicians, was less complete than would have been information secured from druggists; and third, the use by Marshall of population figures for the year 1874 instead of 1877.

From the ninety-six communities heard from, as we have seen, there were reported 1313 users of opium or morphine. For some unknown reason Marshall employs in his computation the state census figures of 1874 rather than an estimated figure for the year 1877 in which the survey was made. The population of Michigan, according to him, was (in 1874) 1,334,031. Employing this figure, he comes to the conclusion that if the number of opium and morphine users holds good for the entire state, the total number in the state would be 7 ,763. Taking into account the natural rate of increase in population between the years 1874 and 1877, this figure would represent a slight overestimate, all other things being equal. However, this is offset by other factors such as the relative incompleteness of the information received from physicians as compared with that received from druggists, and it is fair to assume that this is a minimal figure. How great the error on the side of underestimation is, we have no means of telling.

The fact that in one town, Monroe, the physician addressed reported but one case, while a druggist stated that there were about sixty, is indicative possibly of a very great error in Marshall's total figure, and it must be remembered that the druggists were in a much better position to know the truth than were physicians. They supplied the drugs used and as a rule, especially at the time of Marshall's investigation, when counter sales were legal and a matter of common practice, physicians were called upon only by those opiate users seeking curative treatment for their condition. It is, therefore, doubtful if the medical profession at any time has been in a position to supply anything like a complete list of these cases, while the druggists from the very nature of things in the past could have furnished this information.

It is probable, therefore, that Marshall's figures are very much more incomplete than even he himself believed, and it is quite possible that the actual number of cases in the towns and cities of Michigan from which Marshall received his returns were several times larger than his figures indicated. Be this as it may, his total of 1313 cases represents definite and positive information indicative of the widespread use of these drugs in the State of Michigan over fifty years ago, long before the development of an illicit traffic in opium and its preparations with its resulting artificial impetus to the formation of new cases. If applied to the country as a whole for the year in question, 1874, this figure gives a total of 251,936. This is a startling figure for the period in question and yet in all probability well below the actual one and deserving of the most careful consideration on the part of those who today, with the undoubted existence of new and increasingly powerful factors at work in the stimulation of the use of these drugs, seek to become familiar with the extent of our present narcotic problem.

Iowa Survey, 1884-J. M. Hull

An account of Hull's findings appears in the Biennial Report of the State Board of Health of Iowa for 1885. Hull begins his report with the following:

Although my paper on the opium habit is brief, and but a small part of the sad story told, yet I am inclined to believe it contains some facts regarding this rapidly increasing evil that cannot fail to astonish even those who are well informed, and far more those who have given the subject little or no attention.

Opium is today a greater curse than alcohol and justly claims a large number of helpless victims, which have not come from the ranks of reckless men and fallen women, but the majority of them are to be found among the educated and most honored and useful members of society; and as to sex, we may count out the prostitutes so much given to this vice, and still find females far ahead so far as numbers are concerned. The habit in a vast majority of cases is first formed by the unpardonable carelessness of physicians, who are often too fond of using a little syringe, or of relieving every ache and pain by the administration of an opiate.

To fifteen-hundred circulars sent to druggists in the state of Iowa requesting information on the subject, Hull received 123 replies reporting 235 users of opium in some form. Of these, 86 were men and 129 women.' The form of drug used was morphine, 129; gum opium, 73; laudanum, 12; paregoric, 6; Dover's Powder, 3; and McMunn's Elixir, 4. As to the method of using the drug, he states:

While the drug is used less frequently by the hypodermic method than by the mouth, the former method is gaining ground. The habit may be formed about as readily one way as the other. Those who use it by the mouth as a rule make the most rapid progress, as the drug is easier taken, is free from pain, and larger than the hypodermic dose.

He states that there were about three thousand stores in Iowa where opium was kept for sale and that if reports had come from all in the same ratio, it would have shown the number of users to have been about six thousand. By actual computation on the above basis, we get 5,732. Hull states, however, that his reports were mostly from the small villages, very few coming from the cities where, he states, the habit was far more common. He states further: "From reliable information which I have been able to secure from various sources, I feel safe in saying- that there are in this state over ten thousand people who are constantly under the influence of an opiate and who are wholly unable by any effort of the will to break the habit or even to abstain for seventy-two hours. "

The estimated population of continental United States for 1884 was, according to the U. S. Bureau of the Census, 55,379; 154, and that of the State of Iowa for the same year was 1,742,084.

Using the lower figure of 5,732 obtained in the manner described above as the actual number of users in the State of Iowa, we get 182,215 chronic users for the country as a whole for the year 1884. This must be by far an underestimate, as Hull himself states that he had good reason to believe that there wereover ten thousand in the state.

It is worthy of note that here again, no mention is made of illicit traffic.

Jacksonville, Florida, 1913. E. Terry10

In 1913 Terry, Health Officer of Jacksonville, Florida, collected data relating to the extent of the problem in his city. The figures were not dependent upon voluntary cooperation as in the case of previous collections of such material but were secured through the operation of a local law which required, besides the usual prohibition of sale of opium preparations by druggists without physicians' prescriptions and the keeping of records of all sales, two procedures which resulted in bringing to the health office specific information relating to the extent to which opium preparations were employed. The first of these required physicians writing prescriptions containing more than three grains of morphine or its equivalent in alkaloids or salts of alkaloids of opium to send to the office of the health department copies of such prescriptions together with the names and addresses of the individuals for whom they were intended. Second, it provided that the city health officer or other physician in the employ of the city designated by him might give to any user, upon the furnishing of satisfactory evidence of habitual use, a prescription for as much of such drug as might be deemed expedient.

Records were kept of all duplicate prescriptions sent in and of all those issued at the health office. These prescriptions were free and were designed to remove from druggists the temptation of making counter sales on the plea that indigent users or those of small means could not afford to pay for the writing of a prescription in addition to the cost of the drug. The law was enforced actively, and both druggists and physicians were watched carefully for violations.

No effort was made at this time to limit the use of these drugs in the case of habitual users nor were they subjected to such treatment as might be calculated to discourage them from coming to the health department for a prescription. On the contrary,during the operation of this law-a period of over two years they were supplied upon application. Treatment was offered them from time to time and furnished to such as accepted the offer.

Through the operation of this law there were recorded at the health office during the year 1913, 541 persons using opium or some preparation thereof or about .81 percent of the population of Jacksonville. These were divided into 228 men and 313 women. Of the men, 188 were white and 40 Negro; of the women, 219 white and 94 Negro. The population of Jacksonville for 1913 as estimated by the U.S. Bureau of the Census was 67,209. Of this number, 32,998 were whites and 34,211 Negro. Applied to continental United States on the basis of the estimated population for 1913 of 97,163,330, the Jacksonville incidence gives as the total for the country 782,118.

One source of possible error in figures of this kind exists in the increase which may take place over the normal population of users through the registration of transients. In the case of Jacksonville, however, it would not seem that this was a large factor inasmuch as the registration required either through application to the health office or through the sending of duplicate prescriptions by physicians was not required in nearby states and cities at that time so that it was more difficult for strangers to obtain the drug in Jacksonville than in other nearby points. Whatever this error was, however, it is very much more than offset by the omissions in registration which occurred in the following ways. It was known to the health officer, for instance, that certain business and professional men and other individuals in high social standing who used the drug were never registered but secured their supplies either by mail order from distant points or through friendly physicians or druggists who were willing to risk violating the law for them. Others, through the nature of their employment in drugstores or drug manufacturing concerns, were able easily to supply themselves, while still others went to nearby points outside of the city limits and hence beyond the operation of the ordinance to secure their supply.

What part differences in race composition (other than Negro), economic, occupational, and other sociologic factors may have played in vitiating the Jacksonville figures for purposes of generalization, no one is in position to say at the present time, as enough studies of the prevalence of this condition in other sections of the country have not been made to justify claims either for or against the existence of such influencing factors. In view, however, of the facilities at hand for the collection of the Jacksonville data, it is believed that they represent very complete information. As in a consideration of Marshall's figures for Michigan, it may be assumed that the distribution of painful maladies and the methods of medical practice in Jacksonville did not differ widely from those of other sections. In 1913, however, the influence of prostitution and what is generally termed the underworld obtained much more prominently in Jacksonville than in the localities of Michigan with which Marshall's figures deal, as these were, it will be remembered, all small towns and villages. In the case of the Jacksonville figures, therefore, we may assume that the influence of vicious association was a more marked factor than in the Michigan figures.

The illicit traffic in these drugs was practically negligible in Jacksonville in 1913. One or two peddlers, it is true, supplied certain women in the restricted district more as a matter of convenience to these customers than because of any large profits involved. The traffic could not have been lucrative, as free prescriptions were available to any user asking for them, and the price of the drug in the drugstores was in the neighborhood of sixty cents for a drachm of morphine when sold in original bottles or large fractions. With this price it is evident that peddlers could not compete with profit.

Tennessee, 1915-L. P. Brown 11

Brown, the State Food and Drugs Commissioner of Tennessee, reported on the results of the enforcement of the Tennessee AntiNarcotic Law passed in 1913. The law provided for the refilling of prescriptions for persons using opium products habitually "in order to minimize suffering among this unfortunate class and to keep the traffic in the drug from getting into underground andhidden channels. " The law provided that upon application to the Secretary of the State Board of Health and the Pure Food and Drugs Inspector and upon presentation of a certificate from the attending physician, the name and address of the druggist and certain other data, an individual might be granted permission to have a prescription for an opium product refilled. This system brought a considerable mass of data to the officials concerned. It should be noted in explanation that an effort was made at every renewal of permit to lessen the amount of the drug allowed.

After twelve months of operation there were on January 1,1915, 2370 individuals registered under this system in the state of Tennessee. Of these, 784 were men and 1586 women.

In commenting on the accuracy of the registration Brown states:

As to what proportion of the total addicts of Tennessee are registered under this permissive system, guesses only can be given. It seems safe to say that not over one-half of the addict population is registered-possibly not over one-fourth. Taking, however, the lower figure, it would appear that there are in the neighborhood of five thousand addicts in Tennessee. The state has about 2.3 percent of the whole population of the United States. It is an agricultural state, and consequently, living conditions appear to be not so exhausting as in more thickly settled communities, nor life, as a rule, so intense. In order to get the whole number in the United States, we may multiply our figure of five thousand by forty-three. This gives us about 215,000 addicts. Probably, however, in order to allow for conditions in cities and industrial communities, we ought to add 25 percent to this number, giving not less than 269,000 addicts in the whole United States. In my opinion this is a very conservative calculation. It shows by no means so many as sensational writers appear to want us to believe, and while it thus shows better conditions, it is bad enough.

Brown points out that according to figures which he believes to be fairly accurate, not over 10 percent of the cases were Negro. He says: "This is due in part to the fact that the average Negro avoids as far as possible any contact with an official, and to the fact that the Negro appears to use relatively less morphine and more cocaine than the white man."

The Tennessee figures indicate a very much smaller total for the country than is obtained on the basis of the Jacksonville figures, although these two investigations were made within ayear of each other. The territory covered by the Tennessee law was very much larger than in the case of Jacksonville, and the machinery for enforcement doubtless was less adequate. In Jacksonville, it must be remembered, every physician and every druggist personally was known to the health officer, as were most of the opium users, and it is to be expected that on these accounts more complete information could be secured than where, for the most part as in the case of Tennessee, it was necessary to rely on correspondence without the close personal touch possible in the smaller territory. Brown himself questions the completeness of his figures, stating that in his opinion they comprise a very conservative estimate.

Which of these estimates is nearer the truth for the period in question, no one may state with certainty. It is noteworthy, however, that Brown's figures applied to the countr<> as a whole give a figure but little in excess of that obtained on the basis of the Michigan figures of 1877, about thirty-five years before Brown's work. It scarcely is to be expected that with the influences at work . . . during this period of thirty-five years, there could have failed to be a greater increase than is indicated by these two sets of figures.

The estimates resulting from studies heretofore quoted represent conditions of opium usage freer from artificial influences of one kind or another than any that have been or will be compiled dealing with later periods. Prior to this time there was no federal law relating to the distribution of the drug and . . . very few state laws which were at all rigidly enforced, so that peddling of the drugs was not a marked factor in extending their use. The usual causes mentioned, such as the employment of opium and its products in medicine and self-prescribing for the relief of pain and discomfort, the effect of education through ill-considered articles in the lay press and magazines, fiction, vicious or ignorant associations, and the influence of natural tendencies to dissipation or to seek refuge under stress and strain were operating alone without the additional stimulation of the illicit traffic which was a later development. Wherever, therefore, the exact truth lies as to the number of chronic opium users in the United States prior to the passage of the Harrison Narcotic Act,12 it represents what might be termed the normal for the United States in contradistinction to an artificial or fortuitous figure resulting in addition to the forementioned causes from the perniciously active propaganda of the commercial trader in opium preparations.

United States, 1918-Special Committee of the Treasury Department 13

This committee was unable to determine the exact number of addicts in the United States, owing, as stated in the report, "to the lack of laws and regulations making it compulsory for the registration of addicts throughout the country or the keeping of any records as to their identity." The committee believed, however, that a fairly, accurate estimate of their number can be made from the information which it has obtained.

One source of information was a questionnaire addressed to all physicians registered under the Harrison Narcotic Act, requesting data as to the number of chronic users under treatment by them at the tune. The committee reports as follows:

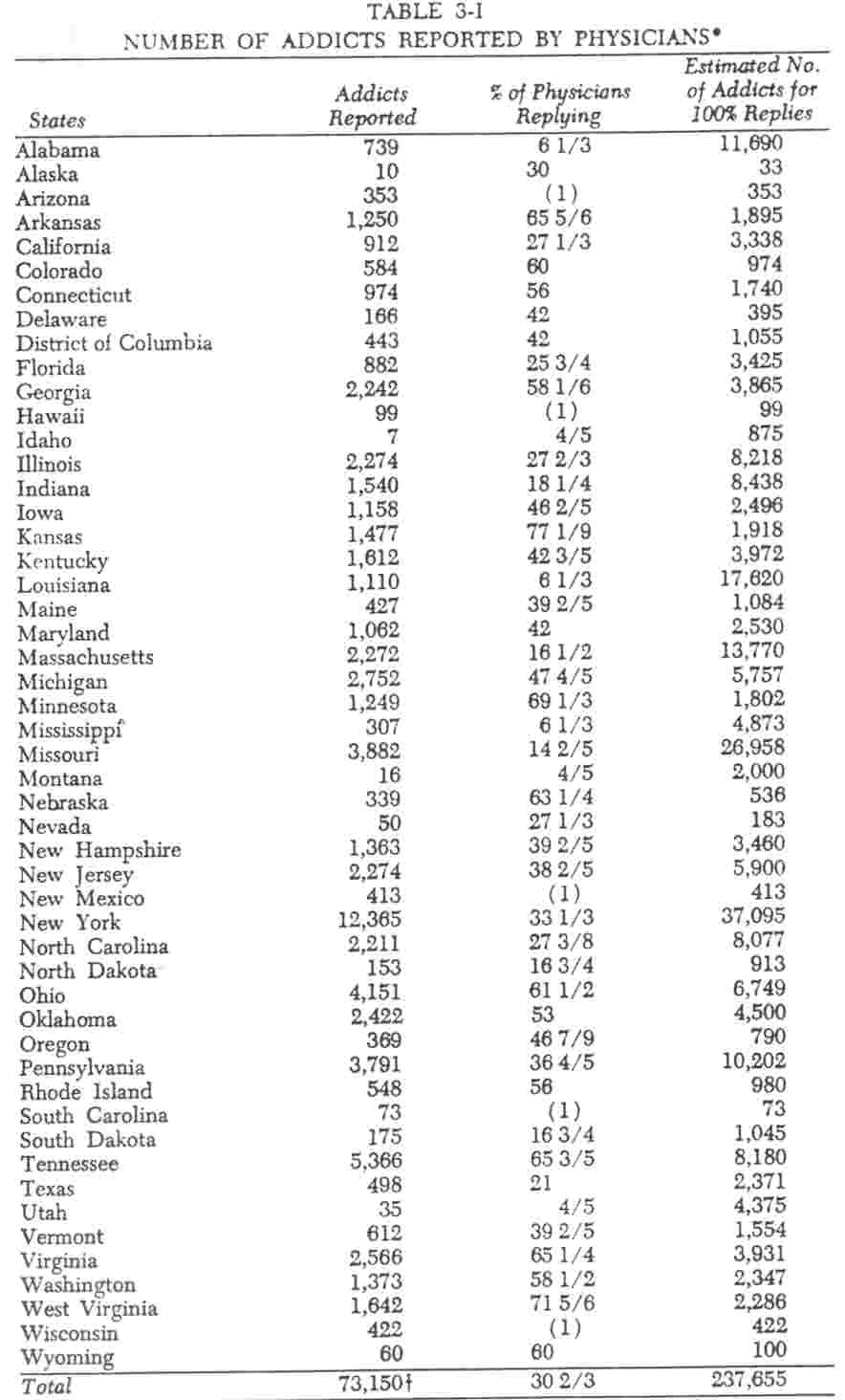

Replies were received from approximately 30a percent of the physicians registered in the different states, and these showed that there were under treatment at that time a total of 73,150 addicts. On the basis of 100 percent replies, if the same average was maintained, there were under treatment at the time this questionnaire was sent out a total of 237,655 addicts. The following table shows in detail by states the number of addicts reported under treatment, the percentage of replies received from physicians, and the estimated number on the basis of 100 percent replies.

Another questionnaire was addressed to state, district, county, and municipal health officers, the results of which are given as follows: "Questionnaire No. 4 was addressed to 3,023 state, district, county, and municipal health officers. To this questionnaire 983 replies were received, or 33 percent of the total number sent out. Only 777 of these, or 26 percent of the total, contained any information of value to the committee."

From Traffic in Narcotic Drugs. Report of Special Committee of Investigation appointed March 25, 1918, by the Secretary of the Treasury. June, 1919. Washington, 1919.

Note: (1) indicates percent replying can not be given, as collectors summarized the data and did not furnish the number of reports.

fi ( This total is, apparently, incorrect; it should be 73,070-The Editors.)

The report summarizes as follows:

The number of addicts reported by the health officials replying to questionnaire No. 4 was 105,887. As this number represents the addicts reported by only 26 percent of the health officials from which this information was requested, it may be assumed that had all the health officials replied, the total number would have amounted to approximately 420,000. This number, however, appears to be much too low in view of the fact that the physicians of the country are estimated to have had about 237,000 addicts under treatment during this same period, and only a small portion of the total number of addicts present themselves for treatment. Addicts of the "underworld," for instance, secure most of their supply through illicit channels and rarely, if ever, consult a physician.

In reply to questionnaire No. 4 sent to health officers of states, counties, and municipalities, the health officer of New York City reported a total of 103,000 addicts, which is equivalent to 1.8 percent of the population. On this basis there would be 1,908,000 addicts in the United States.

Information in the hands of the committee indicates that drug addiction is less prevalent in rural communities than in cities or in congested centers. It would, therefore, be unfair to estimate the number of addicts in the entire country on the basis of the figures obtained for New York City. Furthermore, it is the opinion of the committee that an estimate based on the number of addicts ín a small city like Jacksonville, Fla., would not be representative for the entire country. Taking these facts into consideration, the committee is of the opinion that the total numberof addicts in this country probably exceeds one million at the present time.

In reviewing the estimates arrived at on the basis of the replies received to these questionnaires, there arises a question as to what is meant bytreatment. From a later statement in the Report, treatment here means presumably the supplying of the drug by physicians, but we believe that in replying to this question the average physician would report only such cases as were under curative treatment. Be this as it may, the propriety of estimating the number of cases on the basis of 100 percent replies from physicians registered under the Harrison Narcotic Act is open to question. It is stated in the Report that 30-2/3 percent of the registered physicians queried replied and that 73,150 cases were reported by them as being under treatment. To assume that the resulting figure of 237,655 calculated on such a basis is a correct estimate is still not warranted. For such an estimate to be accepted as a logical conclusion on the basis of 100 percent replies, it would have to be assumed that all groups of physicians registered under the Harrison Narcotic Law answered in like proportion. But it is natural to assume that nose and throat specialists, oculists, obstetricians, gynecologists, surgeons, and others not occupied with general practice would not be interested to the same degree in replying to the questionnaire. In all probability the 30-2/3 percent of physicians reporting include a relatively greater proportion of those treating addiction cases than those not reporting. Under these conditions the estimated 237,655 addicts is too high a figure. As a matter of fact, however, the committee appears not to accept this figure, anyway, inasmuch as it ultimately reaches a speculative figure of 1,000,000 inclusive of cocaine users.

As to the estimates based on replies received from state, county, and municipal health officers of which the committee states only 26 percent replied, we would call attention to the fact that 103,000 were reported by the health commissioner of New York City, with a balance of the 26 percent reporting only 2887. This material was gathered in 1918. At that time also, nothing in the nature of a survey of chronic opium users in New York City had been made. The narcotic clinic was not opened until 1919, and this clinic disclosed but 7464 cases of opium users. It is manifest, therefore, that the 103,000 reported by the health commissioner in the previous year was wholly speculative. It is also of interest to note that the health commissioner of New York City a year or two later stated that twenty thousand was an outside estimate for cases of chronic opium users in New York City.

Here again, however, the committee admits dissatisfaction with the resulting estimate of 420,000, stating that the figure is too low and ultimately arrives at an approximate figure of 1,000,000, including users of cocaine. It is not apparent in the report how this figure is reached.

New York City, 1919-.S. D. Hubbard 14

Hubbard reports on the findings resulting from the data gathered during the operation of this clinic over a period of approximately nine months. This clinic was conducted in cooperation with the New York State Department of Narcotic Drug Control. In regard to the extent of opium usage in New York City, Hubbard states:

The problem of narcotic addiction has been in the public eye for some time, and the differing points of view regarding narcotic addiction have been provocative of some very interesting discussion.

In the Spring of last year, the Federal authorities having made several raids on trafficking physicians and druggists, an acute emergency was created whereby it was feared by some that a panic of these miserable unfortunates would ensue. These conditions caused the New York City Department of Health to open a narcotic relief clinic in order to study and examine into the subject of narcotic drug addiction.

Number of Drug Addicts in New York City

Many opinions regarding the prevalence and frequency of drug addiction have been expressed. No doubt many of these statements are far from true. We do not know who the addicts are, nor how many there are of them, either here or elsewhere in this country. Why? From opinions expressed and from the literature on this subject, we have been led to believe that addiction was allocated with certain definite physical stigmata; pallor, emaciation, nervousness, apprehension, sniffing, needle puncture markings, and tattoo skin evidences; but in actual experience with hundreds of acknowledged drug addicts, persons actually seeking their drug supply, we find, like the weather indications, all such signs failing.

There are drug addicts constitutionally inferior and superior; feeble-minded and strong-minded; physically below and above par; morally inferior and superior. No one class of society seems, in our experience, to enjoy a monopoly in this practice. Our opinions, therefore, regarding the number of drug addicts, here and elsewhere about this country, have very naturally had to be revised. While it was the current opinion to think that they existed in vast numbers estimated by some as one percent of the community, and even 2 and 3 percent by others-we, today, think that this is greatly overestimated.

It was formerly held that drug addiction was so general and so frequent that if the law-the Harrison Act-was enforced, as it should be, a panic would be created by the immense numbers of addicts who would seek relief.

The efforts of the New York City Department of Health, actuatedand urged by the Commissioner of Health, Dr. Royal S. Copeland, showed that this fear of the production of a panic was a false one. Our efforts were given wide publicity, and the cooperation of medical and scientific societies earnestly and zealously sought to help solve this problem. It might be added also that the raids initiated by the Federal authorities-arresting illicit prescribers and dispensers-together with the New York State Narcotic Commission requiring registration of all addicts in this locality, have not occasioned any undue excitement among these individuals. We, naturally, must infer that the enormous number of drug addicts supposed to exist, in this vicinity at least (and it was supposed to be greater here than anywhere else) are mythical and untrue and that therefore the fear of a panic of these miserable unfortunates was negative.

In his conclusion, Hubbard states: "The estimate of 1 percent of our population addicted to the use of narcotic indulgence as a habit-addiction-is very likely greatly exaggerated."

In his general statistics Hubbard gives as the number of users registered during the operation of the clinic (about 9 months) 7464, of which 5882 were men and 1582 were women. Applying the incidence indicated for New York City by the number registered at the clinic, we obtain for the country as a whole 140,554 for the year 1919.

A number of factors combined to make the registration at the New York City clinic incomplete. In the first place, attendance was voluntary. Further, in New York City it required that not more than a 24-hour supply be furnished the addict, so that it was necessary for individuals to visit their physicians or the clinic daily in order to secure the drug legitimately. This requirement tended to influence those for whom it was impossible or too inconvenient to leave their business or work to seek their supply from the illicit traffic or from legitimate sources outside of the jurisdiction of this ruling. The number registered, therefore, represents only those who, because of difficulties in securing their supply by reason of the cost of prescriptions or because the drug was sold more cheaply at the clinic than at the retail drugstore in spite of the 24-hour ruling, chose to attend the clinic.

Also, there were several other factors operating to keep certain classes of users away from the clinic. First, there was the inconvenience of the crowded condition of the clinic, where applicants were required to stand outside in lines a block or more long in any weather waiting their turn to be examined and otherwise attended to. Second, there was the fixing of an arbitrary dosage and then the enforced reduction by an arbitrary amount. Third, it was required that a considerable amount of personal information having nothing to do with their addiction, such as the name of their employers and their addresses, be supplied and that the photograph of the patient be attached to the registration card.

Drug peddling in New York City was very rife at the time of the operation of the clinic, and every opportunity was offered those who could afford to pay the prices charged by the illicit traffickers in drugs to secure their supplies without submitting to the requirements of the 24-hour supply provisions or registration at the clinic.

Shreveport, Louisiana, 1920-W. P. Butler

In many respects the next figures to be considered possess a unique value. They were supplied by W. P. Butler, medical director of the narcotic clinic at Shreveport, Louisiana, and include the cases of chronic opium intoxication in the city of Shreveport and Caddo Parish in which Shreveport is located, comprising thus a territory including both urban and rural population. Further they represent only resident cases. Transients, nonresidents or those who were induced possibly to seek Shreveport because of the opportunity for attending a clinic and profiting by treatment, have all been eliminated by Dr. Butler through his intimate personal knowledge of the circumstances surrounding each case. The size of Shreveport, its relative isolation from populous centers, and the absence of large industries and manufactories would all tend to minimize underworld influences as etiologic factors of importance. For the most part, these cases represent those arising from the prescribing of these drugs by physicians; from self-medication; and from that element which everywhere, even without unusual opportunity or artificial incitement, tends to seek adventure, stimulation, or solace through the use of narcotics. In other words, Butler's figures represent more nearly than any others in our possession what might be termed a normal incidence as existing in a community where unusual exciting causes have not existed.

In using the phrase normal incidence as indicating the cases of chronic opium usage caused through medical practice, self-medication, and constitutional make-up but exclusive of cases stimulated by such artificial influences as underworld association, illicit traffic, and so forth, we would not be understood as meaning that the normal as at present existing is an irreducible figure. We believe only that it is an actual figure existing as of this time the present period in medical practice and lay knowledge-that with better medical education and a more widespread dissemination among the laity of the facts of chronic opium intoxication, this normal in the future materially will be lessened. 15

Further, it should be remembered in considering these figures that the operation of this clinic continued without interruption for a period of nearly four years, from May 3, 1919, to February 10, 1923. This is a longer period of existence than has been comprised in the life of any other narcotic clinic. The methods employed by Butler, differing in several particulars from those employed elsewhere in similar work, and the support from local officials, physicians, and public combined to make this unusual period of existence possible in view of the attitude of the Bureau of Internal Revenue in regard to the operation of narcotic clinics.

The local educational influence of the clinic undoubtedly was very great in Shreveport and the adjoining rural districts, which fact must not be lost sight of in attempting to generalize from the Shreveport figures. Not only the very great majority of all cases were handled personally by Dr. Butler and his staff--only a very few remained in the hands of private physicians-but the nature of the work was so thoroughly understood and so widely endorsed by the local medical profession that it could not have failed to have a deterrent effect upon the ill-advised, careless, or unnecessary prescribing and administering of opium preparations in the ordinary practice of medicine. Therefore, there must have been an influence during the operation of the clinic tending to lessenrather than to increase the number of new cases usually arising from and attributable to the unwise use of opium by the practicing physician at large. In other words, there appear to have been no artificial stimulating influences toward narcotism, but on the contrary, there were present influences which tended distinctly to lessen the formation of new cases.

Also, it should be noted that during the operation of the clinic, the illicit traffic was reduced to the minimum if not wholly eradicated. This matter received the particular attention of the Bureau of Internal Revenue, whose agents repeatedly visited Shreveport and noted the conditions under which the clinic operated. According to Butler, they stated to him as their personal opinion that the drug was very scarce on the streets of Shreveport; one agent made several attempts at different times to buy the drub or to have it bought but was unsuccessful.

It would appear, therefore, that one may generalize with less chance of error, at least on the side of exaggeration, from the Shreveport figures than from those of any other locality. Further, in such generalizations we have a more nearly accurate portrayal of the extent of the use of opium preparations in this country arising from what we may term the more natural causes-causes inherent in all communities in which medicine is practiced, painful illness is experienced, and predisposing constitutional tendencies do not exist in excess or are not influenced unduly by artificial conditions-than in other generalizations.

In other communities, especially in the metropolitan centers and industrial cities where racial, social, and economic factors lead to congested living conditions and tend to stimulate the vicious employment of opium preparations for purposes solely of dissipation, where prostitution is considerably more prevalent, and where peddling is highly profitable, we should expect a very material increase in the underworld or vicious element among the drug-using population as a whole. In addition to this, where public and professional attention has not been continuously and for a relatively long period directed at constructive effort toward the elimination of this evil, we should not look for a decrease in the drug-using population resulting from an increased caution on the part of members of the medical profession.

Whatever the effect of these two influences in the causation of chronic opium intoxication in such large centers as we have referred to here or elsewhere, the cases attributable to them must be considered as an increment in excess of those normally existing in these communities and resulting from such widespread and omnipresent causes as those apparently responsible and chiefly operative in Shreveport.

The Shreveport incidence, therefore, of opium users for the population at large may well be considered a minimum.

Had Butler not eliminated the nonresident and transient cases, the cases recorded at the Shreveport clinic since its inception would be 1,237. This figure, Dr. Butler states, includes transients, residents, nonresidents, and all those dispensed to one time or more and comprises all cases handled by the clinic from the date of its opening to February, 1923. In the case of Shreveport, however, where the collection of information has been made with unusual care and over a considerable period, it has been possible for those in charge of the work to eliminate artificial or unusual conditions and to determine with exactness the true resident incidence. Butler reports this figure to be 371, which covers exclusively those residents registered and cared for during a period of nearly four years .... Doctor Butler has supplied us with the number of addicts treated and registered during one calendar year of the clinic, 1920. The total number of cases treated in this year was 542, but into this figure enters the error incident to the fact that numbers of individuals came to Shreveport throughout the period of the clinic because of the clinic and its facilities. In an attempt to correct for this source of error, it was possible for Doctor Butler to subdivide these 542 cases into residents and nonresidents, the basis for the former being residence in Caddo Parish for a period of one year prior to registration at the clinic. The resident figure for 1920 is 211, the nonresident figure is 331 . . . . The true number which would be typical of Shreveport lies somewhere between the strict resident figure of 211 and the exaggerated figure of 542. The resident figure gives to Shreveport an opium user rate of .25 percent.

Applied to continental United States it would furnish a total of284,276 for 1920. From what already has been said of the conditions under which the Shreveport figures were obtained-the elimination of nonresidents, transients, and drug traffickers-and from the absence of unusual exciting causes which would lead to the formation of any considerable percentage of vicious or underworld cases, it is at once apparent that this figure represents a minimum and must be considerably below the real number. For we may not minimize without danger of serious underestimation what is so often reported by local and federal authorities throughout the country as a powerful influence in the causation of this condition in the younger age groups of both sexes, particularly of males, namely, the etiologic factor comprised in underworld associations and the commercial instinct of the illicit trafficker.

In the preceding pages we have utilized such figures as we have found available in an effort to show the extent of this problem. These figures have been in some cases incomplete and in others, for one reason or another, subject to doubt or controversy. Unfortunately, a sufficient number of local surveys at any given period has not been made to furnish material for a reliable cross-section of the country. Conditions existing in one section may be attacked with at least a show of justice when applied to others. Population composition, occupation, and even climate, to say nothing of many other sociologic influences, tend to vitiate generalizations made from local data of this kind.

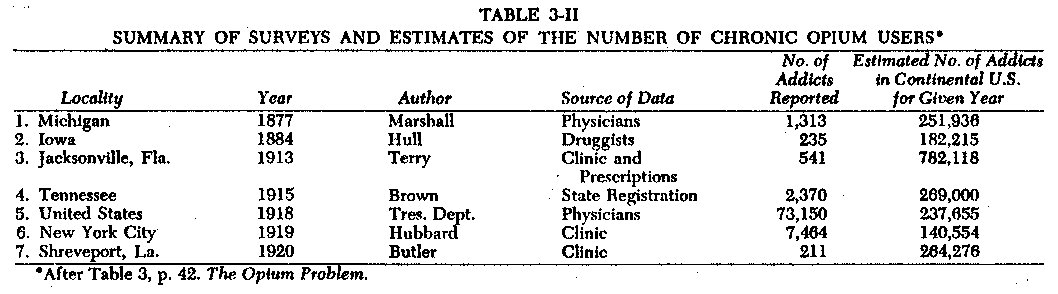

For comparison we are giving in the following table the findings of the surveys suitable for purposes of generalization together with certain computations based thereon. The other surveys of which we have record are too incomplete or for one reason or another too inconclusive to warrant their use as bases for general estimates.

Conclusion

The conclusion is inevitable that the number of chronic users, for one reason or another, steadily has been increasing, as upon the basis of the therapeutic use of these drugs alone-in the treatment of disease other than that of chronic opium intoxication-such an increase would have been impossible. In 1915 two things occurred simultaneously-the importations decreased, and the illicit traffic began to develop. This doubtless was due chiefly to the fact that chronic users, because of the restrictions placed upon physicians and pharmacists in the handling of these drugs, sought their supplies from underworld sources. It does not mean necessarily that the consumption of opium has decreased.

[ We have traced the progress of the development of the problem of chronic opium intoxication] through the early unrestricted use and popularity of opium to relieve pain in that period of medical enlightenment when attention was directed at symptoms rather than cause, the ignorance of the dangers of continued use, the discovery of its value for therapeutic uses, the influence of such writings as De Quincey's and others of his day, the introduction and widespread use of the hypodermic syringe, the influence of the Civil War and other wars, the practice of opium smoking, the influence of the patent medicine industry, the discovery and use of heroin, the illicit traffic which has grown up since the enactment of anti-narcotic laws and the general lack of interest and laxness in medical teachings and practice in the employment of opium preparations.

Whatever their inaccuracies, these surveys and estimates indicate sufficiently clearly the existence of a major medicosocial problem to make the denial of the existence of a general situation far more dangerous than its affirmation. As a matter of fact, it is not necessary to know the exact number of users or even the minimal extent to realize that there are a large number in the country and that the problem is serious.

1. This factor.does not enter into the early surveys which were carried on when illicit traffic was unknown or practically negligible.

2. 'Ludlow, Fitzhugh:Harper's Magazine. August,1867.

3. Day, Horace:The Opium Habit. 1868.

4. Calkins,A.: Opium and the Opium Appetite. Philadelphia,1871.

5. D.M.R. Culbreth in his Materia Afedica and Pharmacology, 3rd edition, 1903, states: "During the Civil War opium was cultivated in Virginia, Tennessee, South Carolina. Georgia, being planted in September and collected in May." In the 8th edition of the same work, the author states that this opium was of high narcotic content.

6. In the selections quoted from Oliver and McFarland, the italics were inserted by the editors for emphasis.

7. McFarfand S.F.; Opium Inebriety and the Hypodermic Syringe. Trans. New York State Medical Society,1877.

8. Marshall, O.: The Opium Habit in Michigan. Annual Report Michigan State Board of Health.1878.

9. This figure appears to be a typographical error. We believe it should be 149 (original note).

10. Terry, C. E.: Annual Report Board of Health, Jacksonville, Fla., 1913.

11. Brown, L. P.: Enforcement of the Tennessee Anti-Narcotic Law. AmericanJournal of Public Health, Vol. 5, No. 4, 1915.

12. The Federal antinarcotic law passed December 17. 1914.

13 Traffic in Narcotic Drugs-Report of Special Committee of Investigation appointed March 25, 1918, by the Secretary of the Treasury, June, 1919, Washington, D.C., 1919.

14 Hubbard, S. D.: The New York City Narcotic Clinic and differing points of view on narcotic addiction. Monthly Bulletin, Dept. of Health, Citv of New York, February, 1920.

15 This paragraph was a footnote (No. 23) in the original text, but the editors have inserted it into the text for clarity.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|