Chapter 1 Overview of the Problem

| Books - Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in United States |

Drug Abuse

The Epidemiology of Opiate Addiction in the United States

Chapter 1

Overview of the Problem

JOAN C. BALL AND CARL D. CHAMBERS

THE principal epidemiological aspects of opiate addiction in the United States have now been established. A series of research studies at the Lexington Hospital and elsewhere, supported for the most part by the National Institute of Mental Health, have provided data as to the scope of the contemporary problem and the natural history of the disease. These national research findings are presented in the present volume.

The Extent of Opiate Addiction

During the past one hundred years there have been numerous studies of drug abuse in the United States which have endeavored to estimate the extent of chronic opium use. Although the results of these surveys have differed somewhat as to the extent of the problem, there is agreement that drug addiction has had an extensive history in this nation.

Within the last decade public awareness and concern with the problem of drug abuse has led to increased scientific and medical research pertaining to the addicting drugs. One important aspect of this augmented research program has been the establishment of new medical files which provide a means of ascertaining the extent and characteristics of opiate addiction throughout the United States.

In our study of two national files of addicts and one metropolitan file, we have devised a statistical procedure for calculating both the incidence and prevalence of chronic opiate use in the United States. For 1967 we have found that there were 108,424 known opiate addicts in the nation; of this number, 30,885 were first reported during this year.

Geographic Distribution

Although opiate addicts live throughout the United States, there is a marked concentration in three states-New York, Illinois, and California. In these states are found 77 percent of the Active Addicts known to the Bureau of Narcotics and 50 percent of the patients admitted to the Lexington and Fort Worth Hospitals (Table I-I). Both the concentration of addicts in the more urbanized states and the absence of opiate users in the rural states is striking. Thus New York, New Jersey, Michigan, and Illinois are high addiction states, while Maine, New Hampshire, Iowa, and the Dakotas have extremely few addicts. It is important in this regard to compare rates of addiction as well as the absolute numbers of drug users.

An analysis of geographic distribution by states somewhat obscures the fact that opiate addiction has become a metropolitan phenomenon. Most addicts live in cities. Furthermore, they tend to be disproportionately concentrated in our largest cities. New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles are the focal points of metropolitan addiction-well over half of the nation's addicts live in these three cities. The remainder of the addict population resides mostly in other large cities; 92 percent of Lexington-Fort Worth patients came from Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas (cities of at least 50,000 population). Still, some opiate addicts live in small towns, especially in the Southern states.

Not only are the users of heroin and other hard narcotics concentrated in our metropolitan centers but they reside in certain sections of these cities. The areas of high rates of drug abuse tend to be deteriorating neighborhoods and slum ghettoes. The reasonfor this ecological concentration is that the onset and continuationof opiate addiction is commonly a group process which requiresthe existence of a drug subculture, and most addicts now livein these slum areas. Conversely, addiction rates are low in stableworking-class and middle-class areas. Perhaps contrary to expectations; drug use is not prevalent in skid row sections of large cities.

Age Distribution of Opiate Addicts

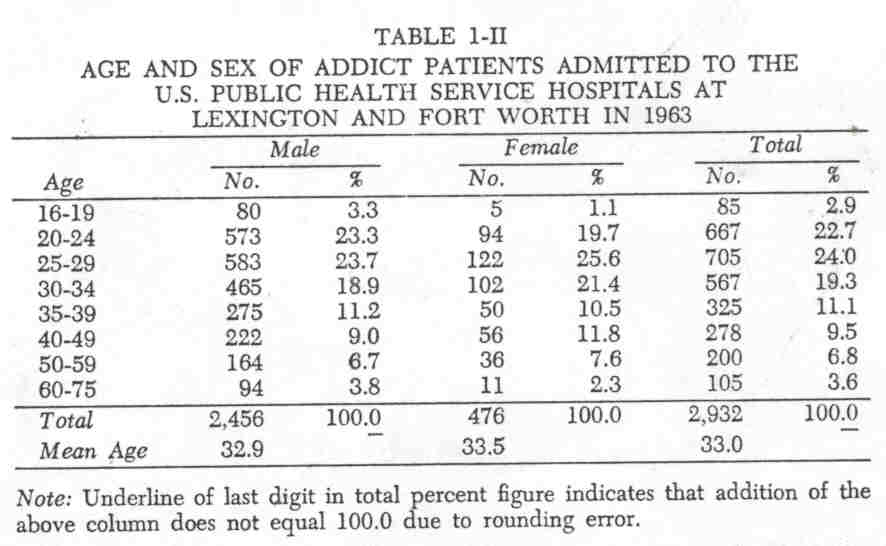

Most addicts in the United States are young adults-80 percent or more are under forty years of age. Of the Bureau's62,045 Active Addicts in 1967, only L3.6 percent were over forty years of age. The New York City Register reported (1964-1967 ) only 8.3 percent of 39,372 heroin users as forty years or older. An age distribution of Lexington-Fort Worth admissions shows that19.9 percent of 2,932 addict patients were forty years of age or older ( Table 1-II).

In considering these age tabulations of heroin and other opiate addicts, two comments seem pertinent. First, it is important to distinguish between current age of an addict population and age at onset of drug abuse; the former is of primary interest to those engaged in treatment programs, the latter to those investigating etiology. Secondly, the question arises as to what happens to addicts after age forty. How important axe mortality, treatment, institutionalization, and maturation in the natural history of addiction?

Sex and Race

The addict population of the United States is predominantly male. In all three major files-The Bureau, The Register, and Lexington-Fort Worth admissions females constitute from 16 to 21 percent of the addict population. At the turn of the century males did not predominate, as drug use was less subject to governmental regulation and it was more evidently associated with medical treatment and the use of patent medicines. With the passage of the Harrison Act in 1914, the situation changed. Drug addiction decreased, but it also became an illegal endeavor. As a consequence of legal controls, opiate use became an illicit undertaking and one in which relatively few females engaged.

The racial and ethnic composition of the U.S. addict population has changed markedly during the past thirty years. In 1936 Pescor found that 11.6 percent of Lexington admissions were nonwhite; by 1966, 56 percent were minority group membersNegro, Mexican, or Puerto Rican. In the years since World War II, there has been a notable increase in opiate use within the black and Spanish-speaking population in northern cities. In the Southern states addiction has continued to be almost exclusively confined to the white population.

Type of Opiate to Which Addicted

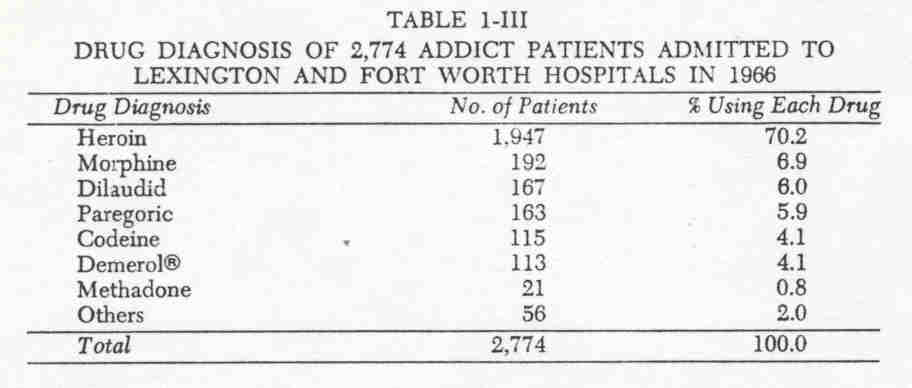

The principal opiate drug of abuse in the United States is heroin. Of the 62,045 Active Addicts known to the Bureau of Narcotics in 1967, 93.4 percent were using this illicit drug. Of2,774 addicts admitted to the Lexington and Fort Worth Hospitals in 1966, 70.2 percent were using heroin, 6.9 percent morphine,6.0 percent Dilaudid®, 5.9 percent paregoric, 4.1 percent codeine,4.1 percent meperidine, 0.8 percent methadone, and 2.0 percent other opiates ( Table 1-III ) . The greater variability of drug use among the federal hospital patients reflects the fact that these were mostly voluntary admissions ( who are not reported to the Bureau or FBI) drawn from wider socioeconomic strata than the criminal addicts reported to the Bureau by police authorities.

Nativity and Mobility

In considering nativity and parentage, it is significant to note that addiction is not transmitted from parents to children nor from new immigrants to settled inhabitants. Our studies have shown that most addicts are native born of native parentage; the foreign born are underrepresented when compared with the general adult population. Furthermore, addicts tend to be reasonably stable in their place of residence-at least they are no more mobile than the U.S. population.

Education and Intelligence of Addicts

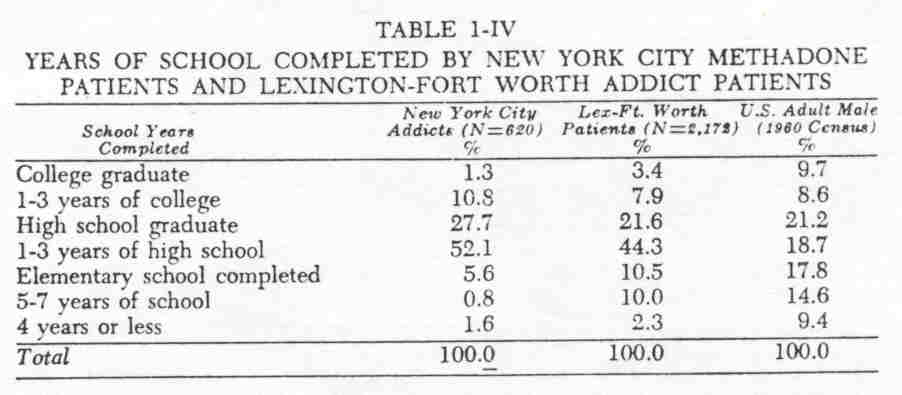

The educational attainment of the addict population is similar to that of the U.S. population, with the exception that there are notablyfewer addicts at the bottom of the school ladder and somewhat fewer who are college graduates. Thus, only 8.0 percent of New York City addicts and 22.8 percent of Lexington Fort Worth patients had not reached high school, compared with 41.8 percent of the adult males in the nation who had eight or fewer years of schooling ( Table I-IV). The Lexington comparison with the general population is more appropriate than that for New York, as the former is national in scope and includes some higher status addicts.

The fact that opiate addicts are not educationally deprived and that, indeed, they not only compare favorably with the general population but undoubtedly are above average in schooling for their respective neighborhoods is provocative. It is especially so when it is realized that many youthful addicts leave school partly as a consequence of drug use, so that one might expect a marked educational retardation.

The data on intelligence test results are similar to those obtained for education. Addicts are notably underrepresented among those with below-average intelligence. Opiate addicts commonly have average or above average intelligence. In a comparison of New York City addicts with the general population, it was found that only 16.9 percent of the addicts were below an intelligence quotient score of 90, compared with 25.0 percent for the controls; in addition, more of the addicts were 120 and above-12.9 versus 8.9 percent. .

Occupation

Most chronic users of opiates are unable or unwilling to maintain steady employment. Of1,352 Lexington male patients admitted for treatment in 1965, 31.0 percent were unemployed,31.7 percent were engaged in illegal occupations ( such as selling drugs, theft, con games, and pimping), and only 33.1 percent were legitimately employed ( 4.1% were not in the labor force).

The deleterious effect of opiate addiction upon employment is one of the principal reasons why drug abuse is a social problem. The extent to which this association between addiction and an unproductive way of life is the result of the drug itself, the hectic hustle for drugs, the search for "kicks," or a culturally based inability to ever establish a legitimate means of livelihood-all of these are crucial questions.

Criminality

Most but not all of the addict population are engaged in criminal activities. Of 2,149 Lexington-Fort Worth patients 86.6 percent had been arrested prior to hospitalization. Still, 13.4 percent had never been arrested, and these addicts had been using opiates for an average of 9.9 years! It is evident, then, that recorded arrests underestimate the extent of criminal behavior some addicts are never arrested although they repeatedly engage in various illegal activities, while others are infrequently caught although they follow a full-time professional criminal career. Inasmuch as opiate addicts do not constitute a homogeneous population, it is necessary to analyze criminality within each of the various segments of the national addict population in order to accurately delineate the relationship of drug use to crime.

Major Culture Groups in the United States

We have noted that the demographic characteristics of the addict population in the United States have materially changed during the past fifty years. Opiate addiction has become more closely associated with metropolitan life, the addict has become more enmeshed in criminality, females are less involved with addiction than formerly, while drug use among minority groups has become more prevalent. In addition to these and other historical changes in the nature of addiction, it is necessary to recognize that opiate addicts do not constitute a homogeneous population. Rather, the addict population consists of a number of quite distinct culture groups. Within each of these major groups the life course of opiate addiction has certain unique features as well as definite similarities which are associated with physical dependence upon the opiates.

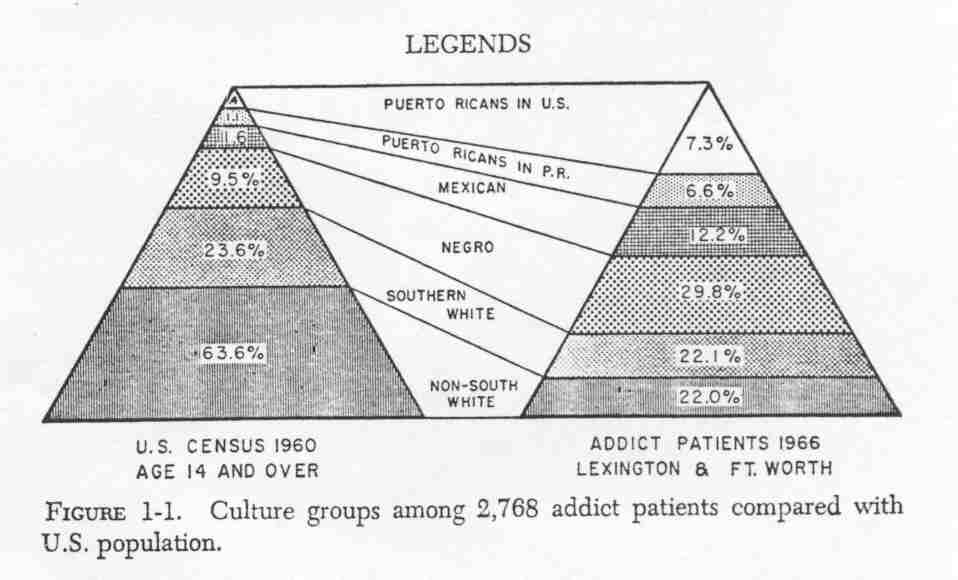

During 1966, 2,774 addict patients were admitted to the Lexington and Fort Worth Hospitals. Most of these were voluntary patients (82.6%) ; the remainder were federal prisoners. They came from forty-six of the fifty states, and all major occupations were represented. Still, despite the geographic distribution of this national sample, it was found that the patient population consisted of six basic culture groups (Fig. 1-1) .

These six major addict groups are the Northern Negro, the Southern white, whites outside the South, Mexicans of the Southwest, Puerto Ricans in the continental U.S., and those in Puerto Rico _(6 Oriental males were excluded from the present comparison). Of the 2,768 addicts 826 were Negro (29.8%) , 611 were Southern whites (22.1%), 609 were other whites (22.0%), 337 were Mexican (12.2%), 203 were Puerto Ricans in the U.S. (7.3%), and 182 were residents of Puerto Rico (6.6%) .

A comparison of these 2,768 addicts with the U.S. population showed that opiate addiction was from three to nine times more prevalent among Negroes, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans than within the general population. That is, these three groups were over represented when compared with their numbers in the general population--56 percent of the 2,768 addicts were Negro, Mexican, or Puerto Rican.

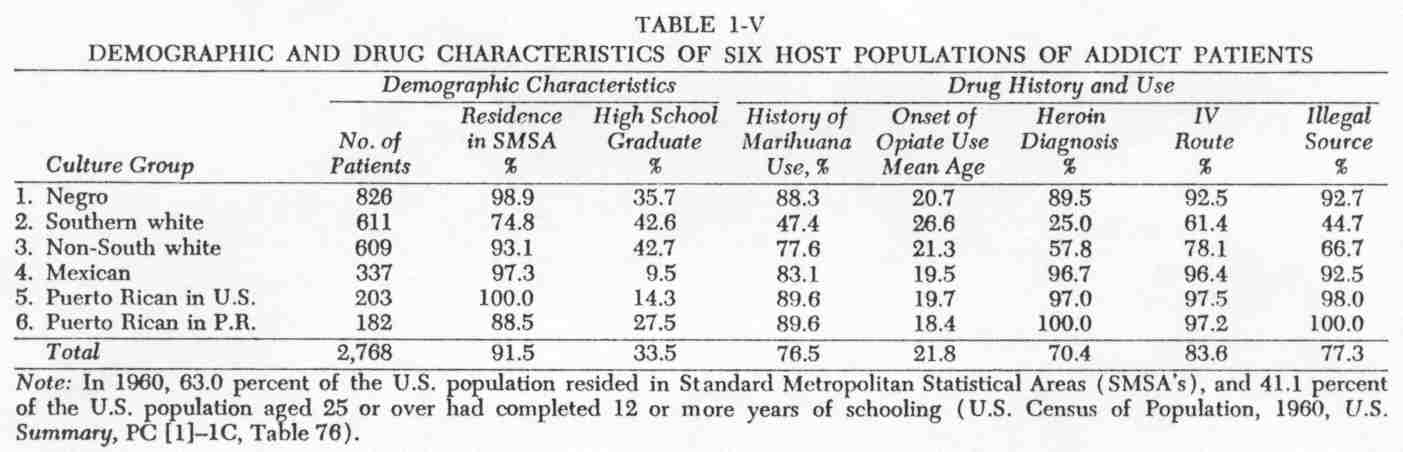

The way of life and pattern of drug use within these six addict populations differ considerably (Table 1-V) . The Negro addicts are almost exclusively metropolitan residents from the North and Midwest; one-third have completed high school. Only 33 percent were employed prior to hospitalization; 21 percentwere unemployed, and 46 percent were engaged in illegal means of support. Onset of opiate use commonly occurred at an early age and was preceded by marihuana smoking. Heroin was the predominant opiate used; it was taken intravenously and obtained from underworld sources.

The Southern white addicts were more frequently residents of small towns than any of the other addict groups, although three-fourths were still residents of Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas. Forty-three percent of the 611 Southern addicts had completed high school; in this respect they were similar to the Negro group. The Southern whites were different, however, in that 51 percent were employed, 30 percent were unemployed, and only 19 percent were engaged in an illegal livelihood. The pattern of drug use among the Southern whites was quite distinct. Onset occurred at a later age, marihuana use was uncommon, opiates other than heroin were commonly used, the intravenous route was less often employed, and drugs were usually obtained from medical or semi legal sources. The Southern pattern of opiate use, then is quite different from that found in northern cities.

The 609 whites from outside the South are a somewhat more heterogeneous group geographically and culturally than the other five patient groups. These addicts came from metropolitan areas throughout the nation excluding the South. As with the prior two groups, somewhat more than a third of the subjects had at least completed high school. Thirty-five percent were employed before hospitalization, 26 percent were unemployed, and 39 percent pursued an illegal means of support. Onset occurred at an early age, and a history of marihuana use was reported for three-fourths of the patients. Heroin use, the intravenous route, and an illegal source of drugs were all less common among these addicts than among the Negro addicts from these metropolitan areas.

The 337 addicts of Mexican ancestry were metropolitan residents from the Southwest-Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. These addicts had the lowest educational attainment of the six groups; only 9.5 percent had completed high school. Most wereblue-collar workers, and few were engaged in illegal careers. For these Mexican addicts onset occurred before age twenty, marihuana use was common, heroin was the predominant opiate, the intravenous route was used, and drugs were secured from illegal sources.

All of the 203 Puerto Rican addicts who lived on the mainland were residents of metropolitan areas-in fact, most lived in New York City. Only 14.3 percent of these addicts had completed high school, and most were either engaged in illegal careers or unemployed--only 18.3 percent were legitimately employed. Their pattern of drug abuse was similar to that of the Negro addicts-early onset, marihuana and heroin use, intravenous administration, and an illegal source of drugs.

The 182 addicts from Puerto Rico were less frequently metropolitan residents than their mainland compatriots, although almost 90 percent lived in the three Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas of the island-San Juan, Mayaguez, and Ponce. The Puerto Rican addicts had higher educational attainment than the other two Spanish-speaking groups; 28 percent had completed high school. Nonetheless, only 23 percent of the Puerto Rican males were employed; 18 percent were unemployed, and 59 percent were engaged in illegal careers. The Puerto Rican addicts began opiate use at an earlier age than any of the other addict groups, had a history of marihuana smoking, preferred the intravenous route, used heroin exclusively at the time of hospitalization in 1966, and secured this drug from illegal sources.

Although these six major cultural groups encompass and reflect the contemporary addict population of the United States, it is worth noting both that other groups have occupied a significant place in the past and that further divisions and analysis of this addict population can be undertaken. In the former regard, the place of the Chinese addicts in the history of opiate use can hardly be overlooked; there have been more than eight hundred Chinese-American patients admitted to the Lexington Hospital alone. The question of why opiate addiction has declined among Chinese-Americans is provocative.

Numerous smaller contemporary addict groups can also be identified and studied. Certainly one of the most intriguing is that of the medical profession particularly doctor and nurse addicts. There were, for example,401 physician addicts discharged from the Lexington Hospital between 1952 and 1964. These were solitary drug users who started their self-administration of meperidine, Dilaudid, or morphine at an older age. Before their addiction they usually had no criminal history. Use of either heroin or marihuana within this group was the exception.

In the five-year period from 1962 to 1966, there were ninety registered nurses admitted to the Lexington Hospital for treatment of opiate addiction. As with the physicians these patients were professional employed people and mostly secured their drugs from medical sources. Of the ninety nurses two-thirds obtained their drugs from doctors or hospital supplies, while the remainder had drugstores, family, fraudulent prescriptions, or "pushers" as their source. These nurses came from thirty states and had a mean age of forty-two years at time of hospitalization.

In addition to medical personnel, one might mention the following subgroups as either numerically significant or theoretically interesting: medically induced addicts, including pain-prone patients; professional drug sellers; jazz musicians; middle-class Jewish addicts; the successful criminal; husband and wife addicts; twins; housewives; prostitutes; and artists.

In considering the composition of the addict population in the United States, we have shown that it is not homogeneous but rather that it includes at least six major culture groups and numerous smaller segments. Further, we have noted that the demographic characteristics of this addict population are not stable but that the composition has changed historically as American society has changed.

Etiology of Opiate Addiction

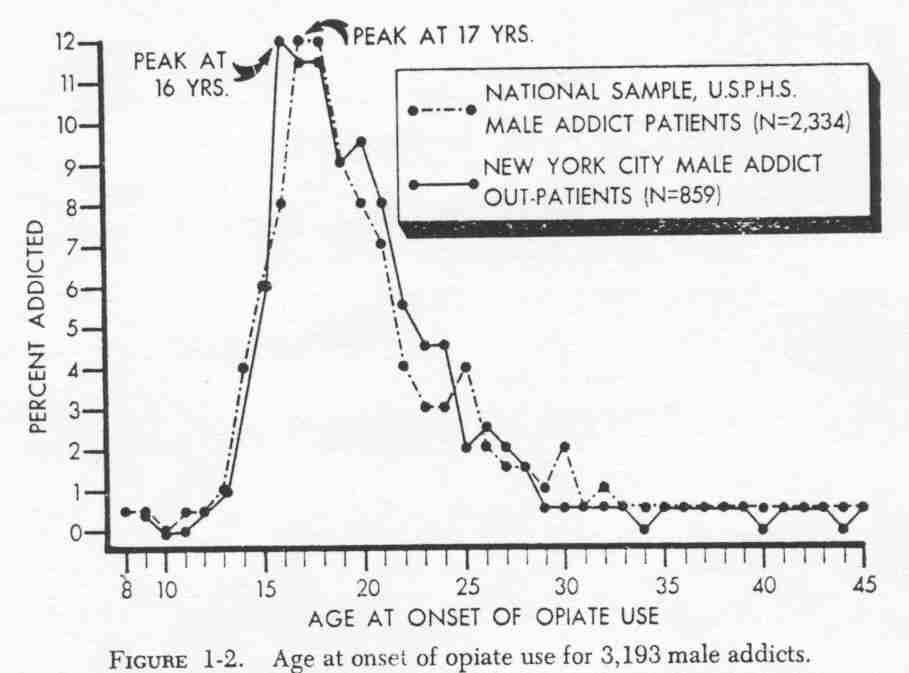

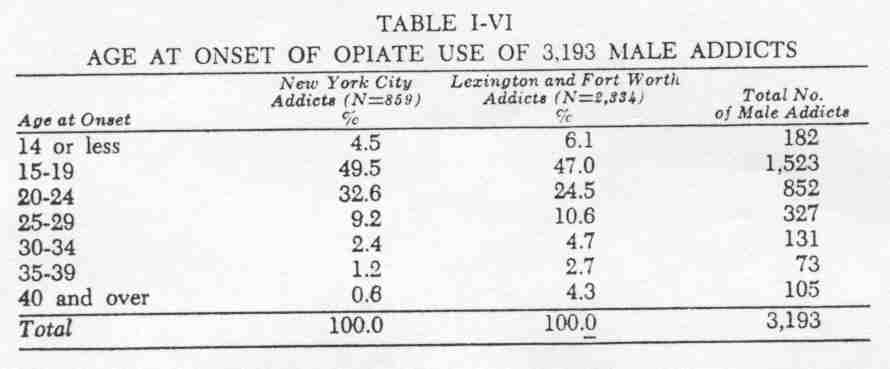

After considering the extent and nature of opiate addiction in America, the question arises as to how and why persons start to use drugs. At what age does use of heroin begin? Under what circumstances? For fun, escape, peer-group status? The age at which onset of opiate use occurred fro 3,1913 male addicts is shown in Table 1-VI and Figure 1-2. Of 2,334 Lexington Fort Worth males 6 percent started using opiates when they were from eight to fourteen years old; 47 percent started at age fifteen to nineteen; 25 percent when they were twenty to twenty-four; 11 percent from twenty-five to twenty-nine years; 7 percent during their thirties; and only 4 percent at age forty or older. Clearly, onset of opiate use is associated with adolescence. The highest incidence was at ages seventeen and eighteen; 61 percent of the boys started to use opiates before age twenty-one.

The New York City series is strikingly similar to the Lexington Fort Worth data; 64 percent of 859 male addicts in the city were under twenty-one years of age at time of onset. The peak year for incidence in New York was age sixteen.

In addition to being an adolescent phenomenon, onset of opiate use is a peer-group recreational experience. It is similar to juvenile delinquency in that the boys are seeking status in the group by taking part in a search for kicks and excitement. Initiation into drug use is voluntary rather than accidental or coercive. The incipient addict asks to join the drug-taking group, and these boys are perceived as friends. Marihuana smoking commonly precedes the onset of opiate use. If opiate use continues, addiction may occur within weeks or a few months after the first group experience with hard narcotics.

Although we have studied in some detail how opiate use commences among adolescents, the propelling personal and societal forces are less well known. Why do some boys become addicts, while others from the same neighborhood or family do not? Is there an addiction-prone personality? Are addicts mentally ill? Do slum youths turn to drugs because of neglect and hopelessness, ignorance of the dangers involved, unrealistic life expectations, or for kicks?

It is now evident that the phenomenon of onset, about which we have a considerable body of knowledge, cannot be explained on the basis of a single prior causal agent or condition. Four points are especially relevant to an etiological consideration of opiate addiction. First, the question of the availability of drugs is of paramount importance; new cases are most likely to occur in areas of high prevalence, and they cannot occur where drugs are not attainable. Second, most opiate addicts are part of a drug subculture, and they began to use drugs at the time then entered this group; consequently, arguments which are based on individual pathology seem inadequate as explanations of a group process. Third, it is necessary to separate onset from those prior conditions or factors which led to the start. of drug use; when this is done, the concept of a single direct causal agent seems inappropriate. Fourth, if mental illness were the principal cause of drug addiction, this condition would have to precede the event and be closely associated with it; there is no evidence that this is so.

The Scope and Method of Our Study

In our study of opiate addiction in the United States, we have adopted the following principles: (a) to place our primary reliance upon known cases of drug abuse and corresponding verifiable knowledge; (b) to take cognizance of a historical perspective; (c) to focus upon national studies of drug abuse; and (d) to stress etiology, incidence, and prevalence of addiction rather than treatment and social policy.

In placing our reliance upon data obtained directly from addicts by means of interview, medical examination, and other established procedures, we were guided by the advice of Terry and Pellens to begin by studying a known population of addicts. Furthermore, we were personally predisposed to emphasize hardrather than soft data. Thus, we found it meaningful to study drug diagnoses of patients as well as the route of administration used, to analyze the reliability and validity of interview data, to take urine specimens in our field studies, to state the source of our research findings, and generally to require empirical substantiation for statements made. We also, in this research process, came to have a great respect for if not an actual dependence upon firsthand knowledge-we learned to place considerable credence in the data before us. Conversely, we tended to eschew theoretical discussions, speculation, and unverifiable or undocumented secondary reports.

The importance of a historical viewpoint in epidemiological research can hardly be overemphasized. Whether it be tuberculosis, smallpox, syphilis, hypertension, or leukemia, a knowledge of past prevalence and conditions seems necessary for a meaningful interpretation of the present extent, nature, and treatment of disease. In the case of chronic opiate use, we are studying an ancient problem and one which has a long history in the United States. Therefore, whenever it seemed relevant and feasible, we have endeavored to compare contemporary addicts and their patterns of drug use with those of the past.

All of the studies included in this volume are national in scope, with the exception of Chapter 10, which is a field investigation of heroin addicts in Puerto Rico. We have emphasized national studies of opiate abuse in order to provide a broad perspective, to facilitate meaningful analysis within diverse addict population's, and to enable comparisons with the general population of the nation.

Lastly, we have been interested in delineating the specific addict populations in the United States and analyzing their diverse patterns of drug abuse. We have asked: Who are the opiate addicts? What way of life and pattern of drug usage does each major group pursue? How did they begin to use drugs?

We have omitted consideration of treatment and policy questions from the present book for two reasons. In the first place, comparative data on treatment outcome has not been available. Secondly, it seemed likely that epidemiological research pertaining to the extent and life course of addiction within major addict groups would make a more significant contribution to our knowledge than a study of changing modes of contemporary treatment. In addition, the likelihood of a definite cure for opiate addiction appeared remote. As to policy, it seemed only that this should follow rather than precede an analysis of the problem.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|