5. South Vietnam: Narcotics in the Nation's Service

| Books - The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia |

Drug Abuse

5. South Vietnam: Narcotics in the Nation's Service

THE BLOODY Saigon street fighting of April-May 1955 marked the end of French colonial rule and the beginning of direct American intervention in Vietnam. When the First Indochina War-came to an end, the French government had planned to withdraw its forces gradually over a two- or three-year period in order to protect its substantial political and economic interests in southern Vietnam. The armistice concluded at Geneva, Switzerland, in July 1954 called for the French Expeditionary Corps to withdraw into the southern half of Vietnam for two years, until an all-Vietnam referendum determined the nation's political future. Convinced that Ho Chi Minh and the Communist Viet Minh were going to score an overwhelming electoral victory, the French began negotiating a diplomatic understanding with the government in Hanoi.(1) But America's moralistic cold warriors were not quite so flexible. Speaking before the American Legion Convention several weeks after the signing of the Geneva Accords, New York's influential Catholic prelate, Cardinal Spellman, warned that, "If Geneva and what was agreed upon there means anything at all, it means . . . taps for the buried hopes of freedom in Southeast Asia! Taps for the newly betrayed millions of Indochinese who must now learn the awful facts of slavery from their eager Communist masters!" (2)

Rather than surrendering southern Vietnam to the "Red rulers' godless goons," the Eisenhower administration decided to create a new nation where none had existed before. Looking back on America's postGeneva policies from the vantage point of the mid 1960s, the Pentagon Papers concluded that South Vietnam "was essentially the creation of the United States":

"Without U.S. support Diem almost certainly could not have consolidated his hold on the South during 1955 and 1956.

Without the threat of U.S. intervention, South Vietnam could not have refused to even discuss the elections called for in 1956 under the Geneva settlement without being immediately overrun by Viet Minh armies.

Without U.S. aid in the years following, the Diem regime certainly, and independent South Vietnam almost as certainly, could not have survived."(3)

The French had little enthusiasm for this emerging nation and its premier, and so the French had to go. Pressured by American military aid cutbacks and prodded by the Diem regime, the French stepped up their troop withdrawals. By April 1956 the once mighty French Expeditionary Corps had been reduced to less than 5,000 men, and American officers had taken over their jobs as advisers to the Vietnamese army.(4) The Americans criticized the french as hopelessly "colonialist" in their attitudes, and French officials retorted that the Americans were naive During this difficult transition period one French official denounced "the meddling Americans who, in their incorrigible guilelessness, believed that once the French Army leaves, Vietnamese independence will burst forth for all to see."(5)

Although this French official was doubtlessly biased, he was also correct. There was a certain naiveness, a certain innocent freshness, surrounding many of the American officials who poured into Saigon in the mid 1950s. The patron saint of America's antiCommunist crusade in South Vietnam was a young navy doctor named Thomas A. Dooley. After spending a year in Vietnam helping refugees in 1954-1955, Dr. Tom Dooley returned to the United States for a whirlwind tour to build support for Premier Diem and his new nation. Dooley declared that France "had a political and economic stake in keeping the native masses backward, submissive and ignorant," and praised Diem as "a man who never bowed to the French." (6) But Dr. Dooley was not just delivering South Vietnam from the "organized godlessness" of the "new Red imperialism," he was offering them the American way. Every time he dispensed medicine to a refugee, he told the Vietnamese "This is American aid." (7) And when the Cosmevo Ambulator Company of Paterson, New Jersey, sent an artificial limb for a young refugee girl, he told her it was "an American leg."(8)

Although Dr. Dooley's national chauvinism seems somewhat childish today, it was fairly widely shared by Americans serving in South Vietnam. Even the CIA's tactician, General Lansdale, seems to have been a strong ideologue. Writing of his experiences in Saigon during this period, General Lansdale later said:

"I went far beyond the usual bounds given a military man after I discovered just what the people on these battlegrounds needed to guard against and what to keep strong.... I took my American beliefs with me into these Asian struggles, as Tom Paine would have done."(9)

The attitude of these crusaders was so strong that it pervaded the press at the time. President Diem's repressive dictatorship became a "one man democracy." Life magazine hailed him as "the Tough Miracle Man of Vietnam," and a 1956 Saturday Evening Post article began: "Two years ago at Geneva, South Vietnam was virtually sold down the river to the Communists. Today the spunky little Asian country is back on its own feet, thanks to a mandarin in a sharkskin suit who's upsetting the Red timetable! (10)

But America's fall from innocence was not long in coming. Only seven years after these journalistic accolades were published, the U.S. Embassy and the CIA-in fact, some of the same CIA agents who had fought for him in 1955-engineered a coup that toppled Diem and left him murdered in the back of an armored personnel carrier. (11) And by 1965 the United States found itself fighting a war that was almost a carbon copy of France's colonial war. The U.S. Embassy was trying to manipulate the same clique of corrupt Saigon politicos that had confounded the French in their day. The U.S. army looked just like the French Expeditionary Corps to most Vietnamese. Instead of Senegalese and Moroccan colonial levies, the U.S. army was assisted by Thai and South Korean troops. The U.S. special forces (the "Green Berets") were assigned to train exactly the same hill tribe mercenaries that the French MACG (the "Red Berets") had recruited ten years earlier.

Given the striking similarities between the French and American war machines, it is hardly surprising that the broad outlines of "Operation X" reemerged after U.S. intervention. As the CIA became involved in Laos in the early 1960s it became aware of the truth of Colonel Trinquier's axiom, "To have the Meo, one must buy their opium." (12) At a time when there was no ground or air transport to and from the mountains of Laos except CIA aircraft, opium continued to flow out of the villages of Laos to transit points such as Long Tieng. There, government air forces, this time Vietnamese and Lao instead of French, transported narcotics to Saigon, where parties associated with Vietnamese political leaders were involved in the domestic distribution and arranged for export to Europe through Corsican syndicates. And just as the French high commissioner had found it politically expedient to overlook the Binh Xuyen's involvement in Saigon's opium trade, the U.S. Embassy, as part of its unqualified support of the Thieu-Ky regime, looked the other way when presented with evidence that members of the regime are involved in the GI heroin traffic. While American complicity is certainly much less conscious and overt than that of the French a decade earlier, this time it was not just opium -but morphine and heroin as well-and the consequences were far more serious. After a decade of American military intervention, Southeast Asia has become the source of 70 percent of the world's illicit opium and the major supplier of raw-materials for America's booming heroin market.

The Politics of Heroin in South Vietnam

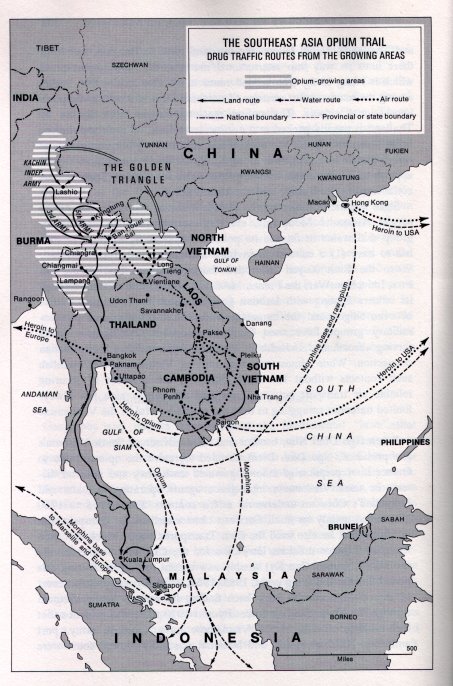

Geography and politics have dictated the fundamental "laws" that have governed South Vietnam's narcotics traffic for the last twenty years. Since opium is not grown inside South Vietnam, all of her drugs have to be importedfrom the Golden Triangle region to the north. Stretching across 150,000 square miles of northeastern Burma, northern Thailand, and northern Laos, the mountainous Golden Triangle is the source of all the opium and heroin sold in South Vietnam. Although it is the world's most important source of illicit opium, morphine, and heroin, the Golden Triangle is landlocked, cut off from local and international markets by long distances and rugged terrain. Thus, once processed and packaged in the region's refineries, the Golden Triangle's narcotics follow one of two "corridors" to reach the world's markets. The first and most important route is the overland corridor that begins as a maze of mule trails in the Shan hills of northeastern Burma and ends as a four-lane highway in downtown Bangkok. Most of Burma's and Thailand's opium follows the overland route to Bangkok and from there finds its way into international markets, the most important of which is Hong Kong. The second route is the air corridor that begins among the scattered dirt airstrips of northern Laos and ends at Saigon's international airport. The opium reaching Saigon from Burma or Thailand is usually packed into northwestern Laos on muleback before being flown into South Vietnam. While very little opium, morphine, or heroin travels from Saigon to Hong Kong, the South Vietnamese capital appears to be the major transshipment point for Golden Triangle narcotics heading for Europe and the United States.

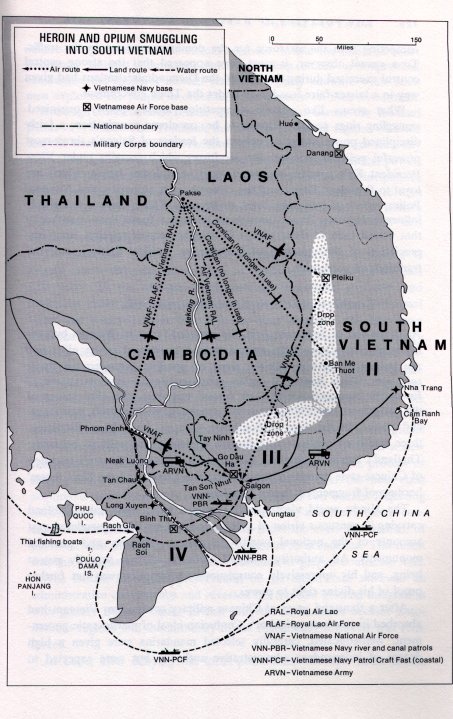

Since Vietnam's major source of opium lies on the other side of the rugged Annamite Mountains, every Vietnamese civilian or military group that wants to finance its political activities by selling narcotics has to have (1) a connection in Laos and (2) access to air transport. When the Binh Xuyen controlled Saigon's opium dens during the First Indochina War, the French MACG provided these services through its officers fighting with Laotian guerrillas and its air transport links between Saigon and the mountain maquis. Later Vietnamese politicomilitary groups have used family connections, intelligence agents serving abroad, and Indochina's Corsican underworld as their Laotian connection. While almost any high-ranking Vietnamese can establish such contacts without too much difficulty, the problem of securing reliable air transport between Laos and the Saigon area has always limited narcotics smuggling to only the most powerful of the Vietnamese elite.

|

|

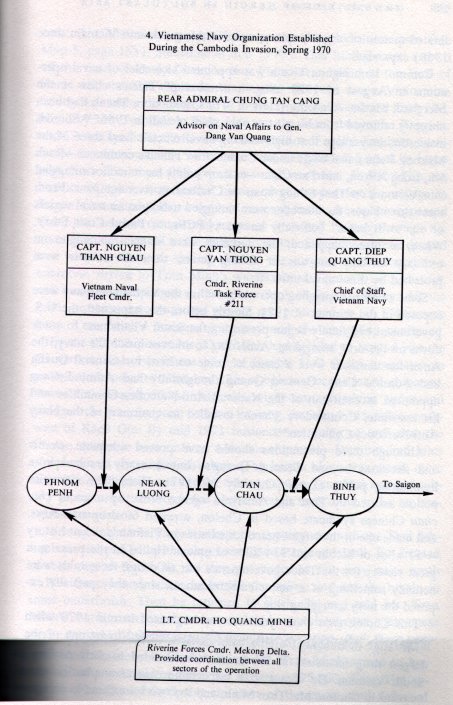

When Ngo Dinh Nhu, brother and chief adviser of South Vietnam's late president, Ngo Dinh Diem, decided to revive the opium traffic to finance his repression of mounting armed insurgency and political dissent, he used Vietnamese intelligence agents operating in Laos and Indochina's Corsican underworld as his contacts. From 1958 to 1960 Nhu relied mainly on small Corsican charter airlines for transport, but in 1961-1962 he also used the First Transport Group (which was then flying intelligence missions into Laos for the CIA and was under the control of Nguyen Cao Ky) to ship raw opium to Saigon. During this period and the following years, 1965-1967, when Ky was premier, most of the opium seems to have been finding its way to South Vietnam through the Vietnamese air force. By mid 1970 there was evidence that high-ranking officials in the Vietnamese navy, customs, army, port authority, National Police, and National Assembly's lower house were competing with the air force for the dominant position in the traffic. To a casual observer, it must have appeared that the strong central control exercised during the Ky and the Diem administrations had given way to a laissez-faire free-for-all under the Thieu government.

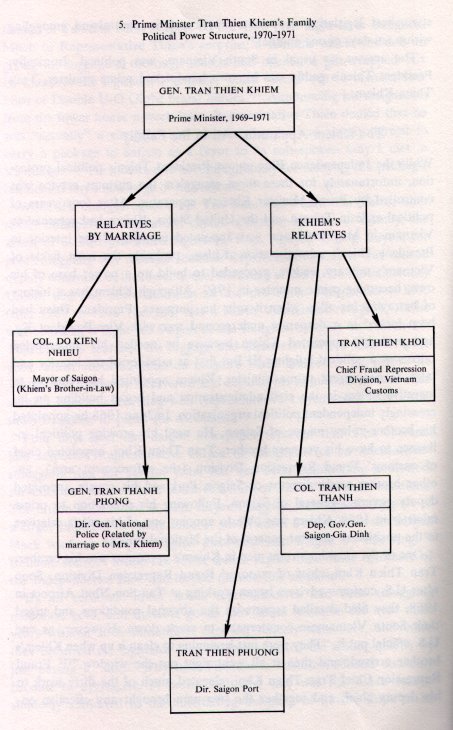

What seems like chaotic competition among poorly organized smuggling rings actually appears to be, on closer examination, a fairly disciplined power struggle between the leaders of Saigon's three most powerful political factions: the air force, which remains under VicePresident Ky's control; the army, navy, and lower house, which are loyal to President Thieu; and the customs, port authority, and National Police, where the factions loyal to Premier Khiem have considerable influence. However, to see through the confusion to the lines of authority that bound each of these groups to a higher power requires some appreciation of the structure of Vietnamese political factions and the traditions of corruption.

Tradition and Corruption in Southeast Asia

As in the rest of Southeast Asia, the outward forms of Western bureaucratic efficiency have been grafted onto a traditional power elite, and the patient is showing all the signs of possible postoperative tissue rejection. While Southeast Asian governments are carbon copies of European bureaucracies in their formal trappings, the elite values of the past govern the behind-the-scenes machinations over graft, patronage, and power. In the area of Southeast Asia we have been discussing, three traditions continue to influence contemporary political behavior: Thailand's legacy of despotic, Hinduized god-kings; Vietnam's tradition of Chinese-style mandarin bureaucrats; and Laos's and the Shan States' heritage of fragmented, feudal kingdoms.

The Hindu world view spread eastward from India into Thailand carrying its sensuous vision of a despotic god-king who squandered vast amounts of the national wealth on palaces, harems, and personal monuments. All authority radiated from his divine, sexually potent being, and his oppressively conspicuous consumption was but further proof of his divine right to power.

After a thousand years of Chinese military occupation, Vietnam bad absorbed its northern neighbor's Confucian ideal of meritocratic government: welleducated, carefully selected mandarins were given a high degree of independent administrative authority but were expected to adhere to rigid standards of ethical behavior. While the imperial court frequently violated Confucian ethics by selling offices to unqualified candidates, the Emperor himself remained piously unaware while such men exploited the people in order to make a return on their investment.

Although Chinese and Indian influence spread across the lowland plains of Vietnam and Thailand, the remote mountain regions of Laos and the Burmese Shan States remained less susceptible to these radically innovative concepts of opulent kingdoms and centralized political power. Laos and the Shan States remained a scattering of minor principalities whose despotic princes and sawbwas usually controlled little more than a single highland valley. Centralized power went no further than loosely organized, feudal federations or individualy powerful fiefdoms that annexed a few neighboring valleys.

The tenacious survival of these antiquated political structures is largely due to Western intervention in Southeast Asia during the last 150 years. In the midnineteenth century, European gunboats and diplomats broke down the isolationist world view of these traditional states and annexed them into their farflung empires. The European presence brought radical innovations-modern technology, revolutionary political ideas, and unprecedented economic oppression-which released dynamic forces of social change, While the European presence served initially as a catalyst for these changes, their colonial governments were profoundly conservative, and allied themselves with the traditional native elite to suppress these new social forces-labor unions, tenants' unions, and nationalist intellectuals. And when the traditional elite proved unequal to the task, the colonial powers groomed a new commercial or military class to serve their interests. In the process of serving the Europeans, both the traditional elite and the new class acquired a set of values that combined the worst of two worlds. Rejecting both their own traditions of public responsibility and the Western concepts of humanism, these native leaders fused the crass materialism of the West with their own traditions of aristocratic decadence. The result was the systematic corruption that continues to plague Southeast Asia.

The British found the preservation of the Shan State sawbwas an administrative convenience and reversed the trend of gradual integration with greater Burma. Under British rule, the Shan States became autonomous regions and the authority of the reactionary sawbwas was reinforced.

In Laos, after denying the local princes an effective voice in the government of their own country for almost fifty years, the French returned these feudalistic incompetents to power overnight when the First Indochina War made it politically expedient for them to Laotianize.

And as the gathering storm of the Vietnamese revolution forced the French to Vietnamize in the early 1950s, they created a government and an army from the only groups at all sympathetic to the French presence -the French-educated, land-owning families and the Catholic minority. When the Americans replaced the French in Indochina in 1955, they confused progressive reform with communism and proceeded to spend the next seventeen years shoring up these corrupted oligarchies and keeping reform governments out of power.

In Thailand a hundred years of British imperial councilors and twenty-five years of American advisers have given the royal government a certain veneer of technical sophistication, but have prevented the growth of any internal revolutions that might have broken with the traditional patterns of corrupted autocratic government.

At the bottom of Thailand's contemporary pyramids of corruption, armies of functionaries systematically plunder the nation and pass money up the chain of command to the top, where authoritarian leaders enjoy an ostentatious life style vaguely reminiscent of the old god-kings. Marshal Sarit, for example, had over a hundred mistresses, arbitrarily executed criminals at public spectacles, and died with an estate of over $150 million. (13) Such potentates, able to control every corrupt functionary in the most remote province, are rarely betrayed during struggles with other factions. As a result, a single political faction has usually been able to centralize and monopolize all Thailand's narcotics traffic. In contrast, the opium trade in Laos and the Shan States reflects their feudal political tradition: each regional warlord controls the traffic in his territory.

Vietnam's political factions are based in national political institutions and compete for control over a centralized narcotics traffic. But even the most powerful Vietnamese faction resembles a house of cards with one mini-clique stacked gracefully, but shakily, on top of another. Pirouetting on top of this latticework is a high-ranking government official, usually the premier or president, who, like the old pious emperors, ultimately sanctions corruption and graft but tries to remain out of the fray and preserve something of an honest, statesmanlike image. But behind every perennially smiling politician is a power broker, a heavy, who is responsible for building up the card house and preventing its collapse. Using patronage and discretionary funds, the broker builds a power base by recruiting dozens of small family cliques, important officeholders, and powerful military leaders. Since these ad hoc coalitions are notoriously unstable (betrayal precedes every Saigon coup), the broker also has to build up an intelligence network to keep an eye on his chief's loyal supporters. Money plays a key role in these affairs, and in the weeks before every coup political loyalties are sold to the highest bidder. Just before President Diem's overthrow in 1963, for example, U.S. Ambassador Lodge, who was promoting the coup, offered to give the plotters "funds at the last moment with which to buy off potential opposition. (14)

Since money is so crucial for maintaining power, one of the Vietnamese broker's major responsibilities is organizing graft and corruption to finance political dealing and intelligence work. He tries to work through the leaders of existing or newly established mini-factions to generate a reliable source of income through officially sanctioned graft and corruption. As the mini-faction sells offices lower on the bureaucratic scale, corruption seeps downward from the national level to the province, district, and village.

From the point of view of collecting money for political activities, the Vietnamese system is not nearly as efficient as the Thai pyramidal structure. Since each layer of the Vietnamese bureaucracy skims off a hefty percentage of the take (most observers feel that officials at each level keep an average of 40 percent for themselves) before passing it up to the next level, not that much steady income from ordinary graft reaches the top. For this reason, large-scale corruption that can be managed by fewer men-such, as collecting "contributions" from wealthy Chinese businessmen, selling major offices, and smuggling-are particularly important sources of political funding. It is not coincidence that every South Vietnamese government that has remained in power for more than a few months since the departure of the French has been implicated in the nation's narcotics traffic.

Diem's Dynasty and the Nhu Bandits

Shortly after the Binh Xuyen gangsters were driven out of Saigon in May 1955, President Diem, a rigidly pious Catholic, kicked off a determined antiopium campaign by burning opium-smoking paraphernalia in a dramatic public ceremony. Opium dens were shut down, addicts found it difficult to buy opium, and Saigon was no longer even a minor transit point in international narcotics traffic. (15) However, only three years later the government suddenly abandoned its moralistic crusade and took steps to revive the illicit opium traffic, The beginnings of armed insurgency in the countryside and political dissent in the cities had shown Ngo Dinh Nhu, President Diem's brother and head of the secret police, that he needed more money to expand the scope of his intelligence work and political repression. Although the CIA and the foreign aid division of the State Department had provided generous funding for those activities over the previous three years, personnel problems and internal difficulties forced the U.S. Embassy to deny his request for increased aid.(16)

But Nhu was determined to go ahead, and decided to revive the opium traffic to provide the necessary funding. Although most of Saigon's opium dens had been shut for three years, the city's thousands of Chinese and Vietnamese addicts were only too willing to resume or expand their habits. Nhu used his contacts with powerful Cholon Chinese syndicate leaders to reopen the dens and set up a distribution network for smuggled opium. (17) Within a matter of months hundreds of opium dens had been reopened, and five years later one Time-Life correspondent estimated that there were twenty-five hundred dens operating openly in Saigon's sister city Cholon. (18)

To keep these outlets supplied, Nhu established two pipelines from the Laotian poppy fields to South Vietnam. The major pipeline was a small charter airline, Air Laos Commerciale, managed by Indochina's most flamboyant Corsican gangster, Bonaventure "Rock" Francisci. Although there were at least four small Corsican airlines smuggling between Laos and South Vietnam, only Francisci's dealt directly with Nhu. According to Lt. Col. Lucien Conein, a former high-ranking CIA officer in Saigon, their relationship began in 1958 when Francisci made a deal with Ngo Dinh Nhu to smuggle Laotian opium into South Vietnam. After Nhu guaranteed his opium shipment safe conduct, Francisci's fleet of twin-engine Beechcrafts began making clandestine airdrops inside South Vietnam on a daily basis. (19)

Nhu supplemented these shipments by dispatching intelligence agents to Laos with orders to send back raw opium on the Vietnamese air force transports that shuttled back and forth carrying agents and supplies. (20)

While Nhu seems to have dealt with the Corsicans personally, the intelligence missions to Laos were managed by the head of his secret police apparatus, Dr. Tran Kim Tuyen. Although most accounts have portrayed Nhu as the Diem regime's Machiavelli, many insiders feel that it was the diminutive ex-seminary student, Dr. Tuyen, who had the real lust and capacity for intrigue. As head of the secret police, euphemistically titled Office of Social and Political Study, Dr. Tuyen commanded a vast intelligence network that included the CIA-financed special forces, the Military Security Service, and most importantly, the clandestine Can Lao party.(21) Through the Can Lao party, Tuyen recruited spies and political cadres in every branch of the military and civil bureaucracy. Promotions were strictly controlled by the central government, and those who cooperated with Dr. Tuyen were rewarded with rapid advancement. (22) With profits from the opium trade and other officially sanctioned corruption, the Office of Social and Political Study was able to hire thousands of cyclo-drivers, dance hall girls ("taxi dancers"), and street vendors as part-time spies for an intelligence network that soon covered every block of Saigon-Cholon. Instead of maintaining surveillance on a suspect by having him followed, Tuyen simply passed the word to his "door-to-door" intelligence net and got back precise, detailed reports on the subject's movements, meetings, and conversations. Some observers think that Tuyen may have had as many as a hundred thousand full- and part-time agents operating in South Vietnam. (23)(24) Through this remarkable system Tuyen kept detailed dossiers on every important figure in the country, including particularly complete files on Diem, Madame Nhu, and Nhu himself which he sent out of the country as a form of personal "life insurance.

Since Tuyen was responsible for much of the Diem regime's foreign intelligence work, he was able to disguise his narcotics dealings in Laos under the cover of ordinary intelligence work. Vietnamese undercover operations in Laos were primarily directed at North Vietnam and were related to a CIA program started in 1954. Under the direction of Col. Edward Lansdale and his team of CIA men, two small groups of North Vietnamese had been recruited as agents, smuggled out of Haiphong, trained in Saigon, and then sent back to North Vietnam in 1954-1955. During this same period Civil Air Transport (now Air America) smuggled over eight tons of arms and equipment into Haiphong in the regular refugee shipments authorized by the Geneva Accords for the eventual use of these teams.(25)

As the refugee exchanges came to an end in May 1955 and the North Vietnamese tightened up their coastal defenses, CIA and Vietnamese intelligence turned to Laos as an alternate infiltration route and listening post. According to Bernard Yoh, then an intelligence adviser to President Diem, Tuyen sent ten to twelve agents into Laos in 1958 after they had completed an extensive training course under the supervision of Col. Le Quang Tung's Special Forces. When Yoh sent one of his own intelligence teams into Laos to work with Tuyen's agents during the Laotian crisis of 1961, he was amazed at their incompetence. Yoh could not understand why agents without radio training or knowledge of even the most basic undercover procedures would have been kept in the field for so long, until he discovered that their major responsibility was smuggling gold and opium into South Vietnam. (26) After purchasing opium and gold, Tuyen's agents had it delivered to airports in southern Laos near Savannakhet or Pakse. There it was picked up and flown to Saigon by Vietnamese air force transports which were then under the command of Nguyen Cao Ky, whose official assignment was shuttling Tuyen's espionage agents back and forth from Laos. (27) Dr. Tuyen also used diplomatic personnel to smuggle Laotian opium into South Vietnam. In 1958 the director of Vietnam's psychological warfare department transferred one of his undercover agents to the Foreign Ministry and sent him to Pakse, Laos, as a consular official to direct clandestine operations against North Vietnam. Within three months Tuyen, using a little psychological warfare himself, had recruited the agent for his smuggling apparatus and had him sending regular opium shipments to Saigon in his diplomatic pouch. (28)

Despite the considerable efforts Dr. Tuyen had devoted to organizing these "intelligence activities" they remained a rather meager supplement to the Corsican opium shipments until May 1961 when newly elected President John F. Kennedy authorized the implementation of an interdepartmental task force report which suggested:

In North Vietnam, using the foundation established by intelligence operations, form networks of resistance, covert bases and teams for sabotage and light harassment. A capability should be created by MAAG in the South Vietnamese Army to conduct Ranger raids and similar military actions in North Vietnam as might prove necessary or appropriate. Such actions should try to avoid the outbreak of extensive resistance or insurrection which could not be supported to the extent necessary to stave off repression.

Conduct overflights for dropping of leaflets to harass the Communists and to maintain the morale of North Vietnamese population . . . .(29)

The CIA was assigned to carry out this mission and incorporated a fictitious parent company in Washington, D.C., Aviation Investors, to provide a cover for its operational company, Vietnam Air Transport. The agency dubbed the project "Operation Haylift." Vietnam Air Transport, or VIAT, hired Col. Nguyen Cao Ky and selected members of his First Transport Group to fly CIA commandos into North Vietnam via Laos or the Gulf of Tonkin. (30)

However, Colonel Ky was dismissed from Operation Haylift less than two years after it began, One of VIAT's technical employees, Mr. S. M. Mustard, reported to a U.S. Senate subcommittee in 1968 that "Col. Ky took advantage of this situation to fly opium from Laos to Saigon. (31) Since some of the commandos hired by the CIA were Dr. Tuyen's intelligence agents, it was certainly credible that Ky was involved with the opium and gold traffic. Mustard implied that the CIA had fired Ky for his direct involvement in this traffic; Col. Do Khac Mai, then deputy commander of the air force, says that Ky was fired for another reason. Some time after one of its two-engine C-47s crashed off the North Vietnamese coast, VIAT brought in four-engine C-54 aircraft from Taiwan. Since Colonel Ky had only been trained in two-engine aircraft he had to make a number of training flights to upgrade his skills; on one of these occasions he took some Cholon dance hall girls for a spin over the city. This romantic hayride was in violation of Operation Haylift's strict security, and the CIA speedily replaced Ky and his transport pilots with Nationalist Chinese ground crews and pilots. (32) This change probably reduced the effectiveness of Dr. Tuyen's Laotian "intelligence activities," and forced Nhu to rely more heavily on the Corsican charter airlines for regular opium shipments.

Even though the opium traffic and other forms of corruption generated enormous amounts of money for Nhu's police state, nothing could keep the regime in power once the Americans had turned against it. For several years they had been frustrated with Diem's failure to fight corruption, In March 1961 a national intelligence estimate done for President Kennedy complained of President Diem:

"Many feel that he is unable to rally the people in the fight against the Communists because of his reliance on one-man rule, his toleration of corruption even to his immediate entourage, and his refusal to relax a rigid system of controls."(33)

The outgoing ambassador, Elbridge Durbrow, had made many of the same complaints, and in a cable to the secretary of state, he urged tha Dr. Tuyen and Nhu be sent out of the country and their secret police be disbanded. He also suggested that Diem make a public announcement of disbandment of Can Lao party or at least its surfacing, with names and positions of all members made known publicly. Purpose of this step would be to eliminate atmosphere of fear and suspicion and reduce public belief in favoritism and corruption, all of which the party's semi-covert status has given rise to.(34)

In essence, Nhu had reverted to the Binh Xuyen's formula for combating urban guerrilla warfare by using systematic corruption to finance intelligence and counterinsurgency operations. However, the Americans could not understand what Nhu was trying to do and kept urging him to initiate "reforms." When Nhu flatly refused, the Americans tried to persuade President Diem to send his brother out of the country. And when Diem agreed, but then backed away from his promise, the U.S. Embassy decided to overthrow Diem.

On November 1, 1963, with the full support of the U.S. Embassy, a group of Vietnamese generals launched a coup, and within a matter of hours captured the capital and executed Diem and Nhu. But the coup not only toppled the Diem regime, it destroyed Nhu's police state apparatus and its supporting system of corruption, which, if it had failed to stop the National Liberation Front (NLF) in the countryside, at least guaranteed a high degree of "security" in Saigon and the surrounding area.

Shortly after the coup the chairman of the NLF, Nguyen Huu Tho, told an Australian journalist that the dismantling of the police state had been "gifts from heaven" for the revolutionary movement:

"... the police apparatus set up over the years with great care by Diem is utterly shattered, especially at the base. The principal chiefs of security and the secret police on which mainly depended the protection of the regime and the repression of the revolutionary Communist Viet Cong movement, have been eliminated, purged."(35)

Within three months after the anti-Diem coup, General Nguyen Khanh emerged as Saigon's new "strong man" and dominated South Vietnam's political life from January 1964 until he, too, fell from grace, and went into exile twelve months later. Although a skillful coup plotter, General Khanh was incapable of using power once he got into office. Under his leadership, Saigon politics became an endless quadrille of coups, countercoups, and demicoups, Khanh failed to build up any sort of intelligence structure to replace Nhu's secret police, and during this critical period none of Saigon's rival factions managed to centralize the opium traffic or other forms of corruption. The political chaos was so severe that serious pacification work ground to a halt in the countryside, and Saigon became an open city.(36) By mid 1964 NLF-controlled territory encircled the city, and NLF cadres entered Saigon almost at will.

To combat growing security problems in the capital district, American pacification experts dreamed up the Hop Tac ("cooperation") program. As originally conceived, South Vietnamese troops would sweep the areas surrounding Saigon and build a "giant oil spot" of pacified territory that would spread outward from the capital region to cover the Mekong Delta and eventually all of South Vietnam. The program was launched with a good deal of fanfare on September 12, 1964, as South Vietnamese infantry plunged into some NLF controlled pineapple fields southwest of Saigon. Everything ran like clockwork for two days until infantry units suddenly broke off contact with the NLF and charged into Saigon to take part in one of the many unsuccessful coups that took place with distressing frequency during General Khanh's twelve-month interregnum.(37)

Although presidential adviser McGeorge Bundy claimed that Hop Tac "has certainly prevented any strangling siege of Saigon, (38) the program was an unqualified failure. On Christmas Eve, 1964, the NLF blew up the U.S. officers' club in Saigon, killing two Americans and wounding fifty-eight more.(39) On March 29, 1965, NLF sappers blew up the U.S. Embassy.(40) In late 1965, one U S. correspondent, Robert Shaplen of The New Yorker, reported that Saigon's security was rapidly deteriorating:

These grave economic and social conditions [the influx of refugees, etc.] have furnished the Vietcong with an opportunity to cause trouble, and squads of Communist propagandists, saboteurs, and terrorists are infiltrating the city in growing numbers; it is even said that the equivalent of a Vietcong battalion of Saigon youth has been taken out, trained, and then sent back here to lie low, with hidden arms, awaiting orders. . . . The National Liberation Front radio is still calling for acts of terror ("One American killed for every city block"), citing the continued use by the Americans of tear gas and cropdestroying chemical sprays, together with the bombing of civilians, as justification for reprisals . . . . (41)

Soon after Henry Cabot Lodge took office as ambassador to South Vietnam for the second time in August 1965, an Embassy briefer told him that the Hop Tac program was a total failure. Massive sweeps around the capital's perimeter did little to improve Saigon's internal security because

The threat-which is substantial-comes from the enemy within, and the solution does not lie within the responsibility of the Bop Tac Council: it is a problem for the Saigon police and intelligence communities. (42)

In other words, modern counterinsurgency planning with its computers and game theories had failed to do the job, and it was time to go back to the tried-and-true methods of Ngo Dinh Nhu and the Binh Xuyen bandits. When the French government faced Viet Minh terrorist assaults and bombings in 1947, they allied themselves with the bullnecked Bay Vien, giving this notorious river pirate a free hand to organize the city's corruption on an unprecedented scale. Confronted with similar problems in 1965-1966 and realizing the nature of their mistake with Diem and Nhu, Ambassador Lodge and the U.S. mission decided to give their full support to Premier Nguyen Cao Ky and his power broker, Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan. The fuzzy-cheeked Ky had a dubious reputation in some circles, and President Diem referred to him as "that cowboy," a term Vietnamese then reserved -,for only the most flamboyant of Cholon gangsters. (43)

The New Opium Monopoly

Premier Ky's air force career began when he returned from instrument flying school in France with his certification as a transport pilot and a French wife. As the Americans began to push the French out of air force advisory positions in 1955, the French attempted to bolster their wavering influence by promoting officers with strong proFrench loyalties to key positions. Since Lieut. Tran Van Ho was a French citizen, he was promoted to colonel "almost overnight" and became the first ethnic Vietnamese to command the Vietnamese air force. Lieutenant Ky's French wife was adequate proof of his loyalty, and despite his relative youth and inexperience, he was appointed commander of the First Transport Squadron. In 1956 Ky was also appointed commander of Saigon's Tan Son Nhut Air Base, and his squadron, which was based there, was doubled to a total of thirty-two C-47s and renamed the First Transport Group. (44) While shuttling back and forth across the countryside in the lumbering C-47s may have lacked the dash and romance of fighter flying, it did have its advantages. Ky's responsibility for transporting government officials and generals provided him with useful political contacts, and with thirty-two planes at his command, Ky had the largest commercial air fleet in South Vietnam. Ky lost command of the Tan Son Nhut Air Base, allegedly, because of the criticism about the management (or mismanagement) of the base mess hall by his sister, Madame Nguyen Thi Ly. But he remained in control of the First Transport Group until the anti-Diem coup of November 1963. Then Ky engaged in some dextrous political intrigue and, despite his lack of credentials as a coup plotter, emerged as commander of the entire Vietnamese air force only six weeks after Diem's overthrow. (45)

As air force commander, Air Vice-Marshal Ky became one of the most active of the "young Turks" who made Saigon political life so chaotic under General Khanh's brief and erratic leadership. While the air force did not have the power to initiate a coup singlehandedly, as an armored or infantry division did, its ability to strafe the roads leading into Saigon and block the movement of everybody else's coup divisions gave Ky a virtual veto power. After the air force crushed the abortive September 13, 1964, coup against General Khanh, Ky's political star began to rise. On June 19, 1965, the ten-man National Leadership Committee headed by Gen. Nguyen Van Thieu appointed Ky to the office of premier, the highest political office in South Vietnam. (46)

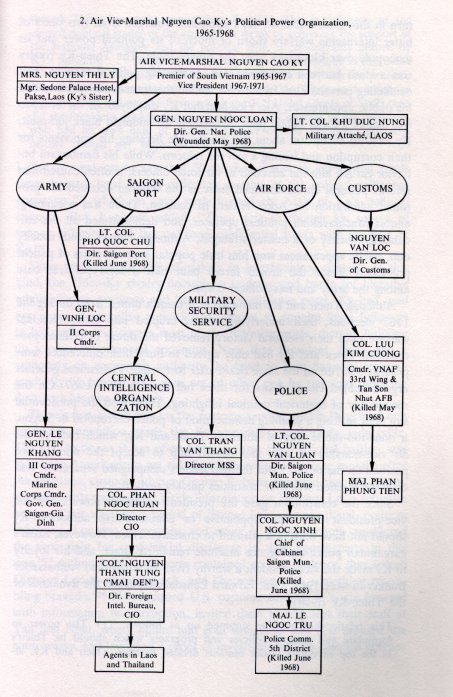

Although he was enormously popular with the air force, Ky had neither an independent political base nor any claim to leadership of a genuine mass movement when he took office. A relative newcomer to politics, Ky was hardly known outside elite circles. Also, Ky seemed to lack the money, the connections, and the capacity for intrigue necessary to build up an effective ruling faction and restore Saigon's security. But he solved these problems in the traditional Vietnamese manner by choosing a power broker, a "heavy" as Machiavellian and corrupt as Bay Vien or Ngo Dinh Nhu-Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan.

Loan was easily the brightest of the young air force officers. His career was marked by rapid advancement and assignment to such technically demanding jobs as commander of the Light Observation Group and assistant commander of the Tactical Operations Center. (47) Loan also had served as deputy commander to Ky, an old classmate and friend, in the aftermath of the anti-Diem coup. Shortly after Ky took office he appointed Loan director of the Military Security Service (MSS). Since MSS was responsible for anticorruption investigations inside the military, Loan was in an excellent position to protect members of Ky's faction. Several months later Loan's power increased significantly when he was also appointed director of the Central Intelligence Organization (CIO), South Vietnam's CIA, without being asked to resign from the MSS. Finally, in April 1966, Premier Ky announced that General Loan had been appointed to an additional post--directorgeneral of the National Police. (48) Only after Loan had consolidated his position and handpicked his successors did he "step down" as director of the MSS and CIO. Not even under Diem had one man controlled so many police and intelligence agencies.

In the appointment of Loan to all three posts, the interests of Ky and the Americans coincided. While Premier Ky was using Loan to build up a political machine, the U.S. mission was happy to see a strong man take command of "Saigon's police and intelligence communities" to drive the NLF out of the capital. Lt. Col. Lucien Conein says that Loan was given whole-hearted U.S. support because

We wanted effective security in Saigon above all else, and Loan could provide that security. Loan's activities were placed beyond reproach and the whole three-tiered US advisory structure at the district, province and national level was placed at his disposal. (49) The liberal naivete that had marked the Kennedy diplomats in the last few months of Diem's regime was decidedly absent. Gone were the qualms about "police state" tactics and daydreams that Saigon could be secure and politics "stabilized" without using funds available from the control of Saigon's lucrative rackets.

With the encouragement of Ky and the tacit support of the U.S. mission, Loan (whom the Americans called "Laughing Larry" because he frequently burst into a high-pitched giggle) revived the Binh Xuyen formula for using systematic corruption to combat urban guerrilla warfare. Rather than purging the police and intelligence bureaus, Loan forged an alliance with the specialists who had been running these agencies for the last ten to fifteen years. According to Lieutenant Colonel Conein, "the same professionals who organized corruption for Diem and Nhu were still in charge of police and intelligence. Loan simply passed the word among these guys and put the old system back together again. (50)

Under Loan's direction, Saigon's security improved markedly. With the "door-todoor" surveillance network perfected by Dr. Tuyen back in action, police were soon swamped with information. (51) A U.S. Embassy official, Charles Sweet, who was then engaged in urban pacification work, recalls that in 1965 the NLF was actually holding daytime rallies in the sixth, seventh, and eighth districts of Cholon and terrorist incidents were running over forty a month in district 8 alone. (See Map 4, page 111.) Loan's methods were so effective, however, that from October 1966 until January 1968 there was not a single terrorist incident in district 8. (52) In January 1968, correspondent Robert Shaplen reported that Loan "has done what is generally regarded as a good job of tracking down Communist terrorists in Saigon .... (53)

Putting "the old system back together again," of course, meant reviving largescale corruption to finance the cash rewards paid to these part-time agents whenever they delivered information. Loan and the police intelligence professionals systematized the corruption, regulating how much each particular agency would collect, how much each officer would skim off for his personal use, and what percentage would be turned over to Ky's political machine. Excessive individual corruption was rooted out, and Saigon-Cholon's vice rackets, protection rackets, and payoffs were strictly controlled. After several years of watching Loan's system in action, Charles Sweet feels that there were four major sources of graft in South Vietnam: (1) sale of government jobs by generals or their wives, (2) administrative corruption (graft, kickbacks, bribes, etc.), (3) military corruption (theft of goods and payroll frauds), and (4) the opium traffic. And out of the four, Sweet has concluded that the opium traffic was undeniably the most important source of illicit revenue. (54)

As Premier Ky's power broker, Loan merely supervised all of the various forms of corruption at a general administrative level; he usually left the mundane problems of organization and management of individual rackets to the trusted assistants.

In early 1966 General Loan appointed a rather mysterious Saigon politician named Nguyen Thanh Tung (known as "Mai Den" or "Black Mai") director of the Foreign Intelligence Bureau of the Central Intelligence Organization. Mai Den is one of those perennial Vietnamese plotters who have changed sides so many times in the last twenty-five years that nobody really knows too much about them. It is generally believed that Mai Den began his checkered career as a Viet Minh intelligence agent in the late 1940s, became a French agent in Hanoi in the 1950s, and joined Dr. Tuyen's secret police after the French withdrawal. When the Diem government collapsed, he became a close political adviser to the powerful I Corps commander, Gen. Nguyen Chanh Thi. However, when General Thi clashed with Premier Ky during the Buddhist crisis of 1966, Mai Den began supplying General Loan with information on Thi's movements and plans. After General Thi's downfall in April 1966, Loan rewarded Mai Den by appointing him to the Foreign Intelligence Bureau. Although nominally responsible for foreign espionage operations, allegedly Mai Den's real job was to reorganize opium and gold smuggling between Saigon and Laos.(55)

Through his control over foreign intelligence and consular appointments, Mai Den would have had no difficulty in placing a sufficient number of contact men in Laos. However, the Vietnamese military attache in Vientiane, Lt. Col. Khu Duc Nung, (56) and Premier Ky's sister in Pakse, Mrs. Nguyen Thi Ly (who managed the Sedone Palace Hotel), were Mai Den's probable contacts.

Once opium had been purchased, repacked for shipment, and delivered to a pickup point in Laos (usually Savannakhet or Pakse), a number of methods were used to smuggle it into South Vietnam. Although no longer as important as in the past, airdrops in the Central Highlands continued. In August 1966, for example, U.S. Green Berets on operations in the hills north of Pleiku were startled when their hill tribe allies presented them with a bundle of raw opium dropped by a passing aircraft whose pilot evidently mistook the tribal guerrillas for his contact men.(57) Ky's man in the Central Highlands was 11 Corps commander Gen. Vinh Loc.58 He was posted there in 1965 and inherited all the benefits of such a post. His predecessor, a notoriously corrupt general, bragged to colleagues of making five thousand dollars for every ton of opium dropped into the Central Highlands.

While Central Highland airdrops declined in importance and overland narcotics smuggling from Cambodia had not yet developed, large quantities of raw opium were smuggled into Saigon on regular commercial air flights from Laos. The customs service at Tan Son Nhut was rampantly corrupt, and Customs Director Nguyen Van Loc was an important cog in the Loan fund-raising machinery. In a November 1967 report, George Roberts, then chief of the U.S. customs advisory team in Saigon, described the extent of corruption and smuggling in South Vietnam:

"Despite four years of observation of a typically corruption ridden agency of the GVN [Government of Vietnam], the Customs Service, I still could take very few persons into a regular court of law with the solid evidence I possess and stand much of a chance of convicting them on that evidence. The institution of corruption is so much a built in part of the government processes that it is shielded by its very pervasiveness. It is so much a part of things that one can't separate "honest" actions from "dishonest" ones. Just what is corruption in Vietnam? From my personal observations, it is the following:

The very high officials who condone, and engage in smuggling, not only of dutiable merchandise, but undercut the nation's economy by smuggling gold and worst of all, that unmitigated evil--opium and other narcotics;

The police officials whose "check points" are synonymous with "shakedown points";

The high government official who advises his lower echelons of employees of the monthly "kick in" that he requires from each of them; . . .

The customs official who sells to the highest bidder the privilege of holding down for a specific time the position where the graft and loot possibilities are the greatest."(58)

It appeared that Customs Director Loc devoted much of his energies to organizing the gold and opium traffic between Vientiane, Laos, and Saigon. When 114 kilos of gold were intercepted at Tan Son Nhut Airport coming from Vientiane, George Roberts reported to U.S. customs in Washington that "There are unfortunate political overtones and implications of culpability on the part of highly placed personages. (59), (60) Director Loc also used his political connections to have his attractive niece hired as a stewardess on Royal Air Lao, which flew several times a week between Vientiane and Saigon, and used her as a courier for gold and opium shipments. When U.S. customs advisers at Tan Son Nhut ordered a search of her luggage in December 1967 as she stepped off a Royal Air Lao flight from Vientiane they discovered two hundred kilos of raw opium.(61) In his monthly report to Washington, George Roberts concluded that Director Loc was "promoting the day-to-day system of payoffs in certain areas of Customs' activities."(62)

After Roberts filed a number of hard-hitting reports with the U.S. mission, Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker called him and members of the customs advisory team to the Embassy to discuss Vietnamese "involvement in gold and narcotics smuggling." (63) The Public Administration Ad Hoc Committee on Corruption in Vietnam was formed to deal with the problem. Although Roberts admonished the committee, saying "we must stop burying our heads in the sand like ostriches" when faced with corruption and smuggling, and begged, "Above all, don't make this a classified subject and thereby bury it," the U.S. Embassy decided to do just that. Embassy officials whom Roberts described as advocates of "the noble kid glove concept of hearts and minds" had decided not to interfere with smuggling or large-scale corruption because of "pressures which are too well known to require enumeration."(64)

Frustrated at the Embassy's failure to take action, an unknown member of U.S. customs leaked some of Roberts' reports on corruption to a Senate subcommittee chaired by Sen. Albert Gruening of Alaska. When Senator Gruening declared in February 1968 that the Saigon government was "so corrupt and graft-ridden that it cannot begin to command the loyalty and respect of its citizens," (65) U.S. officials in Saigon defended the Thieu-Ky regime by saying that "it had not been proved that South Vietnam's leaders are guilty of receiving 'rake-offs." (66) A month later Senator Gruening released evidence of Ky's 1961-1962 opium trafficking, but the U.S. Embassy protected Ky from further investigations by issuing a flat denial of the senator's charges. (67)

While these sensational exposes of smuggling at Tan Son Nhut's civilian terminal grabbed the headlines, only a few hundred yards down the runway VNAF C-47 military transports loaded with Laotian opium were landing unnoticed. Ky did not relinquish command of the air force until November 1967, and even then he continued to make all of the important promotions and assignments through a network of loyal officers who still regarded him as the real commander. Both as premier and vice-president, Air Vice-Marshal Ky refused the various official residences offered him and instead used $200,000 of government money to build a modern, air-conditioned mansion right in the middle of Tan Son Nhut Air Base. The "vice-presidential palace," a pastelcolored monstrosity resembling a Los Angeles condominium, is only a few steps away from Tan Son Nhut's runway, where helicopters sit on twentyfourhour alert, and a minute down the road from the headquarters of his old unit, the First Transport Group. As might be expected, Ky's staunchest supporters were the men of the First Transport Group. Its commander, Col. Luu Kim Cuong, was considered by many informed observers to be the unofficial "acting commander" of the entire air force and a principal in the opium traffic. Since command of the First Transport Group and Tan Son Nhut Air Base were consolidated in 1964, Colonel Cuong not only had aircraft to fly from southern Laos and the Central Highlands (the major opium routes), but also controlled the air base security guards and thus could prevent any search of the C-47s.(68)

Once it reaches Saigon safely, opium is sold to Chinese syndicates who take care of such details as refining and distribution. Loan's police used their efficient organization to "license" and shake down the thousands of illicit opium dens concentrated in the fifth, sixth, and seventh wards of Cholon and scattered evenly throughout the rest of the capital district.

Although morphine base exports to Europe had been relatively small during the Diem administration, they increased during Ky's administration as Turkey began to phase out production in 1967-1968. And according to Lt. Col. Lucien Conein, Loan profited from this change:

"Loan organized the opium exports once more as a part of the system of corruption. He contacted the Corsicans and Chinese, telling them they could begin to export Laos's opium from Saigon if they paid a fixed price to Ky's political organization." (69)

Most of the narcotics exported from South Vietnam-whether morphine base to Europe or raw opium to other parts of Southeast Asia-were shipped from Saigon Port on oceangoing freighters. (Also, Saigon was probably a port of entry for drugs smuggled into South Vietnam from Thailand.) The director of the Saigon port authority during this period was Premier Ky's brother-in-law and close political adviser, Lt. Col. Pho Quoc Chu (Ky had divorced his French wife and married a Vietnamese).(70) Under Lieutenant Colonel Chu's supervision all of the trained port officers were systematically purged, and in October 1967 the chief U.S. customs adviser reported that the port authority "is now a solid coterie of GVN [Government of Vietnam military officers. (71) However, compared to the fortunes that could Se made from the theft of military equipment, commodities, and manufactured goods, opium was probably not that important.

Loan and Ky were no doubt concerned about the critical security situation in Saigon when they took office, but their real goal in building up the police state apparatus was political power. Often they seemed to forget who their "enemy" was supposed to be, and utilized much of their police-intelligence network to attack rival political and military factions. Aside from his summary execution of an NLF suspect in front of U.S. television cameras during the 1968 Tet offensive, General Loan is probably best known to the world for his unique method of breaking up legislative logjams during the 1967 election campaign. A member of the Constituent Assembly who proposed a law that would have excluded Ky from the upcoming elections was murdered. (72) widow publicly accused General Loan of having ordered the assassination. When the assembly balked at approving the ThieuKy slate unless they complied with the election law, General Loan marched into the balcony of the assembly chamber with two armed guards, and the opposition evaporated . (73) When the assembly hesitated at validating the fraudulent tactics the Thieu-Ky slate had used to gain their victory in the September elections, General Loan and his gunmen stormed into the balcony, and once again the representatives saw the error of their ways. (74)

Under General Loan's supervision, the Ky machine systematically reorganized the network of kickbacks on the opium traffic and built up an organization many observers feel was even more comprehensive than Nhu's candestine apparatus. Nhu had depended on the Corsican syndicates to manage most of the opium smuggling between Laos and Saigon, but their charter airlines were evicted from Laos in early 1965. This forced the Ky apparatus to become much more directly involved in actual smuggling than Nhu's secret police had ever been. Through personal contacts in Laos, bulk quantities of refined and raw opium were shipped to airports in southern Laos, where they were picked up and smuggled into South Vietnam by the air force transport wing. The Vietnamese Customs Service was also controlled by the Ky machine, and substantial quantities of opium were flown directly into Saigon on regular commercial air flights from Laos , , Once the opium reached the capital it was distributed to smoking dens throughout the city that were protected by General Loan's police force. Finally, through its control over the Saigon port authority, the Ky apparatus was able to derive considerable revenues by taxing Corsican morphine exports to Europe and Chinese opium and morphine shipments to Hong Kong. Despite the growing importance of morphine exports, Ky's machine was still largely concerned with its own domestic opium market. The GI heroin epidemic was still five years in the future.

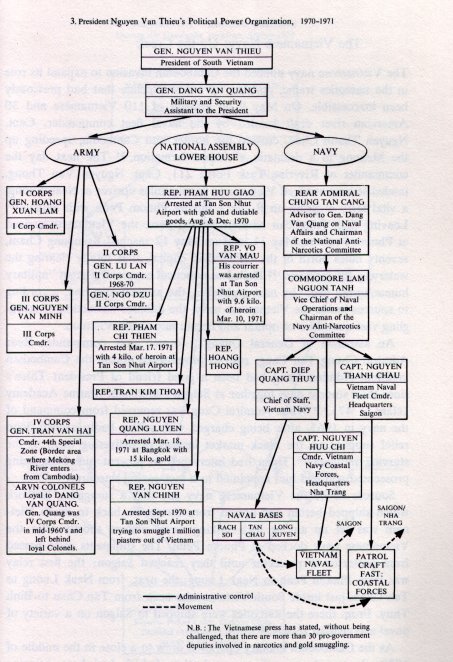

The Thieu-Ky Rivalry

Politics built Premier Ky's powerful syndicate, and politics weakened it. His meteoric political rise had enabled his power broker, General Loan, to take control of the police-intelligence bureaucracy and use its burgeoning resources to increase their revenue from the lucrative rackets -which in Saigon always includes the flourishing narcotics trade. However, in 1967 simmering animosity between Premier Ky and Gen. Nguyen Van Thieu, then head of Saigon's military junta, broke into open political warfare. Outmaneuvered by this calculating rival at every turn in this heated conflict, Ky's apparatus emerged from two years of bitter internecine warfare shorn of much of its political power and its monopoly over kickbacks from the opium trade. The Thieu-Ky rivalry was a clash between ambitious men, competing political factions, and conflicting personalities. In both his behind-the-scenes machinations and his public appearances, Air ViceMarshal Ky displayed all the bravado and flair of a cocky fighter pilot. Arrayed in his midnight black jumpsuit, Ky liked to barnstorm about the countryside berating his opponents for their corruption and issuing a call for reforms. While his flamboyant behavior earned him the affection of air force officers, it often caused him serious political embarrassment, such as the time he declared his profound admiration for Adolf Hitler. In contrast, Thieu was a cunning, almost Machiavellian political operator, and demonstrated all the calculating sobriety of a master strategist. Although Thieu's tepid, usually dull, public appearances won him little popular support, years of patient politicking inside the armed forces built him a solid political base among the army and navy officer corps.

Although Thieu and Ky managed to present a united front during the 1967 elections, their underlying enmity erupted into bitter factional warfare once their electoral victory removed the threat of civilian government. Thieu and Ky had only agreed to bury their differences temporarily and run on the same ticket after forty-eight Vietnamese generals argued behind closed doors for three full days in June 1967. On the second day of hysterical political infighting, Thieu won the presidential slot after making a scathing denunciation of police corruption in Saigon, a none-too-subtle way of attacking Loan and Ky, which reduced the air vice-marshal to tears and caused him to accept the number-two position on the ticket. (75) But the two leaders campaigned separately, and once the election was over hostilities quickly revived.

Since the constitution gave the president enormous powers and the vicepresident very little appointive or administrative authority, Ky should not have been in a position to challenge Thieu. However, Loan's gargantuan policeintelligence machine remained intact, and his loyalty to Ky made the vicepresident a worthy rival. In a report to Ambassador Bunker in May 1968, Gen. Edward Lansdale explained the dynamics of the Thieu-Ky rivalry:

"This relationship may be summed Lip as follows: ( I ) The power to formulate and execute policies and programs which should be Thieu's as the top executive leader remains divided between Thieu and Ky, athough Thieu has more power than Ky. (2) Thieu's influence as the elected political leader of the country, in terms of achieving the support of the National Assembly and the political elite, is considerably limited by Ky's influence . . . (Suppose, for example, a U.S. President in the midst of a major war had as Vice President a leader who had been the previous President, who controlled the FBI, CIA, and DIA [Defense Intelligence Agency], who had more influence with the JCS [Joint Chiefs of Staff] than did the President, who had as much influence in Congress as the President, who had his own base of political support outside Congress, and who neither trusted nor respected the President.)" (76)

Lansdale went on to say that "Loan has access to substantial funds through extra legal money-collecting systems of the police /intelligence apparatus," (77) which, in large part, formed the basis of Ky's political strength. But, Lansdale added, "Thieu acts as though his source of money is limited and has not used confidential funds with the flair of Ky. (78)

Since money is the key to victory in interfactional contests of this kind, the Thieu-Ky rivalry became an underground battle for lucrative administrative positions and key police-intelligence posts. Ky had used two years of executive authority as premier to appoint loyal followers to high office and corner most of the lucrative posts, thereby building up a powerful financial apparatus. Now that President Thieu had a monopoly on appointive authority, he tried to gain financial strength gradually by forcing Ky's men out of office one by one and replacing them with his own followers.

Thieu's first attack was on the customs service, where Director Loc's notorious reputation made the Ky apparatus particularly vulnerable. The first tactic, as it has often been in these interfactional battles, was to use the Americans to get rid of an opponent. Only three months after the elections, customs adviser George Roberts reported that his American assistants were getting inside information on Director Loc's activities because "this was also a period of intense inter-organizational, political infighting. Loc was vulnerable, and many of his lieutenants considered the time right for confidential disclosure to their counterparts in this unit." (79) Although the disclosures contained no real evidence, they forced Director Loc to counterattack, and "he reacted with something resembling bravado." (80) He requested U.S. customs advisers to come forward with information on corruption, invited them to augment their staff at Tan Son Nhut, where opium and gold smuggling had first aroused the controversy, and launched a series of investigations into customs corruption. When President Thieu's new minister of finance had taken office, he had passed the word that Director Loc was on the way out. But Loc met with the minister, pointed out all of his excellent anticorruption work, and insisted on staying in office. But then, as Roberts reported to Washington, Thieu's faction delivered the final blow:

"Now, to absolutely assure Loc's destruction, his enemies have turned to the local press, giving them the same information they had earlier given to this unit. The press, making liberal use of innuendo and implication, had presented a series of front page articles on corruption in Customs. They are a strong indictment of Director Loc."(81)

Several weeks later Loc was fired from his job (82) and the way was open for the Thieu faction to take control over the traffic at Tan Son Nhut Airport.

The Thieu and Ky factions were digging in for all-out war, and it seemed that these scandals would continue for months, or even years. However, on January 31, 1968, the NLF and the North Vietnamese army launched the Tet offensive and 67,000 troops attacked 102 towns and cities across South Vietnam, including Saigon itself. The intense fighting, which continued inside the cities for several months, disrupted politics asusual while the government dropped everything to drive the NLF back into the rice paddies. But not only did the Tet fighting reduce much of Saigon-Cholon to rubble, it decimated the ranks of Vice-President Ky's trusted financial cadres and crippled his political machine. In less than one month of fighting during the "second wave" of the Tet offensive, no less than nine of his key fund raisers were killed or wounded.

General Loan himself was seriously wounded on May 5 while charging down a blind alley after a surrounded NLF soldier. An AK-47 bullet severed the main artery in his right leg and he was forced to resign from command of the police to undergo surgery and months of hospitalization. (83) The next day Col. Luu Kim Cuong, commander of the air force transport wing and an important figure in Ky's network, was shot and killed while on operations on the outskirts of Saigon. (84)

While these two incidents would have been enough to seriously weaken Ky's apparatus, the mysterious incident that followed a month later dealt a crippling blow. On the afternoon of June 2, 1968, a coterie of Ky's prominent followers were meeting, for reasons never satisfactorily explained, in a command post in Cholon. At about 6:00 P.M. a U.S. helicopter, prowling the skies above the ravaged Chinese quarter on the lookout for NLF units, attacked the building, rocketing and strafing it. Among the dead were: Lt. Col. Pho Quoc Chu; director of the Saigon port authority and Ky's brother-in-law. Lt. Col. Dao Ba Phuoc, commander of the 5th Rangers, which were assigned to the Capital Military District. Lt. Col. Nguyen Van Luan, director of the Saigon Municipal Police. Major Le Ngoc Tru, General Loan's right-hand man and police commissioner of the fifth district. Major Nguyen Bao Thuy, special assistant to the mayor of Saigon. Moreover, General Loan's brother-in-law, Lt. Col. Van Van Cua, the mayor of Saigon, suffered a shattered arm and resigned to undergo four months of hospitalization. (85)

These represented the financial foundation of Ky's political machine, and once they were gone his apparatus began to crumble. As vicepresident, Ky had no authority to appoint anyone to office, and all of the nine posts vacated by these casualties, with the exception of the air force transport command, were given to Thieu's men. On June 6 a loyal Thieu follower, Col, Tran Van Hai, was appointed director-general of the National Police and immediately began a rigorous purge of all of Loan's men in the lower echelons. (86) The Saigon press reported that 150 secret police had been fired and a number of these had also been arrested. (87)On June 15 Colonel Hai delivered a decisive blow to Ky's control over the police by dismissing eight out of Saigon's eleven district police commissioners. (88)

As Ky's apparatus weakened, his political fortunes went into a tailspin: loss of minor district and municipal police posts meant he could not collect protection money from ordinary businesses or from the rackets; as the "extra legal money-collecting systems of the police/intelligence apparatus" began to run dry, he could no longer counter President Thieu's legal appointive power with gifts; and once the opposition weakened, President Thieu began to fire many high-ranking pro-Ky police-intelligence officials. (89)

While the quiet desertion of the ant-army bureaucracy to the Thieu machine was almost imperceptible to outside observers, the desertion of Ky's supporters in the National Assembly's cash-and-carry lower house was scandalously obvious. Shortly after the October 1967 parliamentary elections were over and the National Assembly convened for the first time since the downfall of Diem, the Thieu and Ky machines had begun competing for support in the lower house. (90) Using money provided by General Loan, Ky had purchased a large bloc of forty-two deputies, the Democratic Bloc, which included Buddhists, southern intellectuals, and even a few hill tribesmen. Since Thieu lacked Ky's "confidential funds," he had allied himself with a small twenty-one-man bloc, the Independence Bloc, comprised mainly of right-wing Catholics from northern and central Vietnam. (91) Both men were paying each of their deputies illegal supplemental salaries of $4,000 to $6,000 a year, in addition to bribes ranging up to $1,800 on every important ballot. (92) At a minimum it must have been costing Ky $15,000 to $20,000 a month just to keep his deputies on the payroll, not to mention outlays of over $100,000 for the particularly critical showdown votes that came along once or twice a year. In May 1968 General Lansdale reported to Ambassador Bunker that "Thieu's efforts . . . to create a base of support in both Houses have been made difficult by Ky's influence among some important senators . . . and Ky's influence over the Democratic Bloc in the Lower House." (93) However, throughout the summer of 1968 Ky's financial difficulties forced him to cut back the payroll, and representatives began drifting away from his bloc.

As Thieu's financial position strengthened throughout the summer, his assistant in charge of relations with the National Assembly approached a number of deputies and reportedly offered them from $1,260 to $2,540 to join a new proThieu faction called the People's Progress Bloc. One deputy explained that "in the last few months, the activities of the lower house have become less and less productive because a large number of deputies have formed a bloc for personal interests instead of political credits." In September The Washington Post reported:

"The "Democratic Bloc," loyal to Vice President Ky, now retains 25 out of its 42 members. Thieu and Ky have been privately at odds since 1966. Thieu's ascendancy over his only potential rival has grown substantively in recent months.

The severe blow dealt to the Ky bloc in the House has not been mentioned extensively in the local press except in the daily Xay Dung (To Construct), which is a Catholic, pro-Ky paper." (94)

These realignments in the balance of political power had an impact on the opium traffic. Despite his precipitous political decline, Air ViceMarshal Ky retained control over the air force, particularly the transport wing. Recently, the air force's transport wing has been identified as one of the most active participants in South Vietnam's heroin smuggling (see pages 187-188). Gen. Tran Thien Khiem, minister of the interior (who was to emerge as a major faction leader himself when he became prime minister in September 1969) and a nominal Thieu supporter, inherited control of Saigon's police apparatus, Tan Son Nhut customs, and the Saigon port authority. However, these noteworthy internal adjustments were soon dwarfed in importance by two dramatic developments in South Vietnam's narcotics trafficthe increase in heroin and morphine base exports destined for the American market and the heroin epidemic among American GIs serving in South Vietnam.

The GI Heroin Epidemic

The sudden burst of heroin addiction among GIs in 1970 was the most important development in Southeast Asia's narcotics traffic since the region attained self-sufficiency in opium production in the late 1950s. By 1968-1969 the Golden Triangle region was harvesting close to one thousand tons of raw opium annually, exporting morphine base to European heroin laboratories, and shipping substantial quantities of narcotics to Hong Kong both for local consumption and reexport to the United States. Although large amounts of chunky, low-grade no. 3 heroin were being produced in Bangkok and, the Golden Triangle for the local market, there were no laboratories anywhere in Southeast Asia capable of producing the fine-grained, 80 to 99 percent pure, no. 4 heroin. However, in late 1969 and early 1970, Golden Triangle laboratories added the final, dangerous ether precipitation process and converted to production of no. 4 heroin. Many of the master chemists who supervised the conversion were Chinese brought in specially from Hong Kong. In a June 1971 report, the CIA said that conversion from no. 3 to no. 4 heroin production in the Golden Triangle "appears to be due to the sudden increase in demand by a large and relatively affluent market in South Vietnam." By mid April 1971 demand for no. 4 heroin both in Vietnam and the United States had increased so quickly that the wholesale price for a kilo jumped to $1,780 from $1,240 the previous September. (95)

Once large quantities of heroin became available to American GIs in Vietnam, heroin addiction spread like a plague. Previously nonexistent in South Vietnam, suddenly no. 4 heroin was everywhere: fourteen-year old girls were selling heroin at roadside stands on the main highway from Saigon to the U.S. army base at Long Binh; Saigon street peddlers stuffed plastic vials of 95 percent pure heroin into the pockets of GIs as they strolled through downtown Saigon; and "mama-sans," or Vietnamese barracks' maids, started carrying a few vials to work for sale to on-duty GIs. With this kind of aggressive sales campaign the results were predictable: in September 1970 army medical officers questioned 3,103 soldiers of the Americal Division and discovered that 11.9 percent had tried heroin since they came to Vietnam and 6.6 percent were still using it on a regular basis. (96) In November a U.S. engineering battalion in the Mekong Delta reported that 14 percent of its troops were on heroin. (97) By mid 1971 U.S. army medical officers were estimating that about 10 to 15 percent, or 25,000 to 37,000 of the lower-ranking enlisted men serving in Vietnam were heroin users. (98)

As base after base was overrun by these ant-armies of heroin pushers with their identical plastic vials, GIs and officers alike started asking themselves why this was happening. Who was behind this heroin plague? The North Vietnamese were frequently blamed, and wild rumors started floating around U.S. installations about huge heroin factories in Hanoi, truck convoys rumbling down the Ho Chi Minh Trail loaded with cases of plastic vials, and heroin-crazed North Vietnamese regulars making suicide charges up the slopes of Khe Sanh with syringes stuck in their arms. However, the U.S. army provost marshal laid such rumors to rest in a 1971 report, which said in part:

"The opium-growing areas of North Vietnam are concentrated in mountainous northern provinces bordering China. Cultivation is closely controlled by the government and none of the crop is believed to be channeled illicitly into international markets. Much of it is probably converted into morphine and used for medical purposes." (99)

Instead, the provost marshal accused high-ranking members of South Vietnam's government of being the top "zone" in a four-tiered heroinpushing pyramid:

"Zone 1, located at the top or apex of the pyramid, contains the financiers, or backers of the illicit drug traffic in all its forms. The people comprising this group may be high level, influential political figures, government leaders, or moneyed ethnic Chinese members of the criminal syndicates now flourishing in the Cholon sector of the City of Saigon. The members comprising this group are the powers behind the scenes who can manipulate, foster, protect, and promote the illicit traffic in drugs." (100)

But why are these powerful South Vietnamese officials-the very people who would lose the most if the heroin plague forced the U.S. army to pull out of South Vietnam completely-promoting and protecting the heroin traffic? The answer is $88 million. Conservatively estimated, each one of the twenty thousand or so GI addicts in Vietnam spends an average of twelve dollars a day on four vials of heroin. Added up over a year this comes out to $88 million, an irresistible amount of money in an impoverished, war-torn country.