The Khiem Apparatus: All in the Family

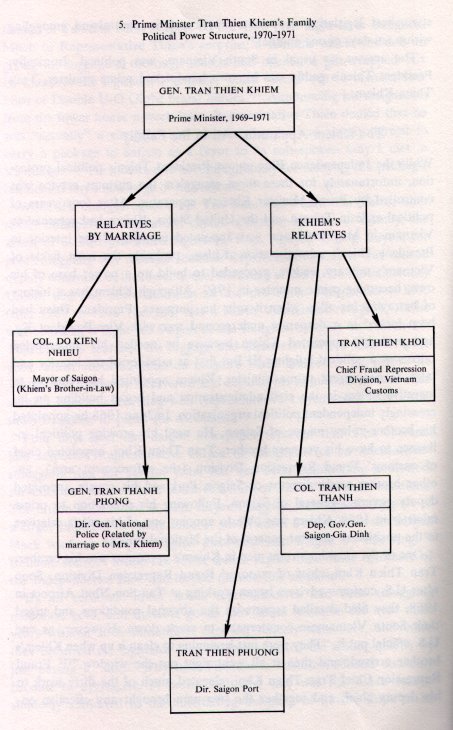

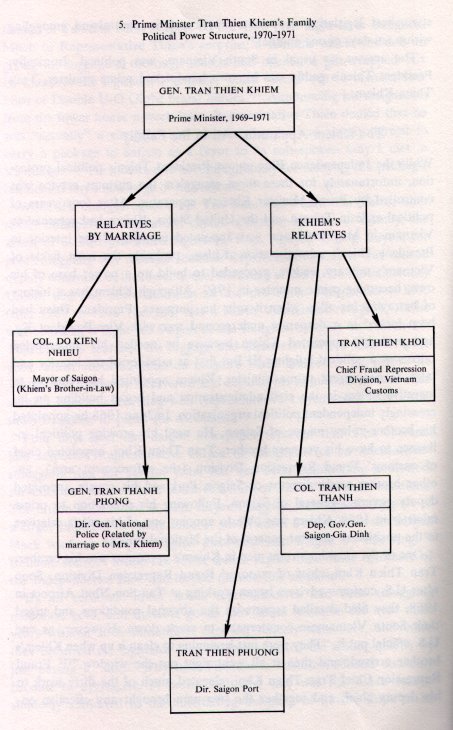

While the Independence Bloc enjoys President Thieu's political protection, unfortunately for these three smugglers the customs service was controlled by Prime Minister Khiem's apparatus. After four years of political exile in Taiwan and the United States, Khiem had returned to Vietnam in May 1968 and was appointed minister of the interior in President Thieu's administration. Khiem, probably the most fickle of Vietnam's military leaders, proceeded to build up a power base of his own, becoming prime minister in 1969. Although Khiem has a history of betraying his allies when it suits his Purposes, President Thieu had been locked in a desperate underground war with Vice-President Ky, and probably appointed Khiem because he needed his unparalleled talents as a political infighter. (176) But first as minister of the interior and later as concurrent prime minister, Khiem appointed his relatives to lucrative offices in the civil administration and began building an increasingly independent political organization. In June 1968 he appointed his brother-in-law mayor of Saigon. He used his growing political influence to have his younger brother, Tran Thien Khoi, appointed chief of customs' Fraud Repression Division (the enforcement arm), another brother made director of Saigon Port and his cousin appointed deputy governor-general of Saigon. Following his promotion to prime minister in 1969, Khicm was able to appoint one of his wife's relatives to the position of director-general of the National Police.

One of the most important men in Khiem's apparatus was his brother, Tran Thien Khoi, chief of customs' Fraud Repression Division. Soon after U.S. customs advisers began working at Tan Son Nhut Airport in 1968, they filed detailed reports on the abysmal conditions and urged their South Vietnamese counterparts to crack down. However, as one U.S. official put it, "They were just beginning to clean it up when Khiem's brother arrived, and then it all went right out the window. (177) Fraud Repression Chief Tran Thien Khoi relegated much of the dirty work to his deputy chief, and together the two men brought any effective enforcement work to a halt. (178) Chief Khoi's partner was vividly described in a 1971 U.S. provost marshal's report:

He has an opium habit that costs approximately 10,000 piasters a day [$35] and visits a local opium den on a predictable schedule. He was charged with serious irregularities approximately two years ago but by payoffs and political influence, managed to have the charges dropped. When he took up his present position he was known to be nearly destitute, but is now wealthy and supporting two or three wives. (179)

The report described Chief Khoi himself as "a principal in the opium traffic" who had sabotaged efforts to set up a narcotics squad within the Fraud Repression Division. (180) Under Chief Khoi's inspired leadership, gold and opium smuggling at Tan Son Nhut became so blatant that in February 1971 a U.S. customs adviser reported that ". . . after three years of these meetings and countless directives being issued at all levels, the Customs operation at the airport has . . . reached a point to where the Customs personnel of Vietnam are little more than lackeys to the smugglers . . ." (181) The report went on to describe the partnership between customs officials and a group of professional smugglers who seem to run the airport:

Actually, the Customs Officers seem extremely anxious to please these smugglers and not only escort them past the examination counters but even accompany them out to the waiting taxis. This lends an air of legitimacy to the transaction so that there could be no interference on the part of an over zealous Customs Officer or Policeman who might be new on the job and not yet know what is expected of him. (182)

The most important smuggler at Tan Son Nhut Airport was a woman with impressive political connections:

"One of the biggest problems at the airport since the Advisors first arrived there and the subject of one of the first reports is Mrs. Chin, or Ba Chin or Chin Map which in Vietnamese is literally translated as "Fat Nine." This description fits her well as she is stout enough to be easily identified in any group.... This person heads a ring of 10 or 12 women who are present at every arrival of every aircraft from Laos and Singapore and these women are the recipients of most of the cargo that arrives on these flights as unaccompanied baggage. . . . When Mrs. Chin leaves the Customs area, she is like a mother duck with her brood as she leads the procession and is obediently followed by 8 to 10 porters who are carrying her goods to be loaded into the waiting taxis....

I recall an occasion . . . in July 1968 when an aircraft arrived from Laos.... I expressed an interest in the same type of Chinese medicine that this woman had received and already left with. One of the newer Customs officers opened up one of the packages and it was found to contain not medicine but thin strips of gold.... This incident was brought to the attention of the Director General but the Chief of Zone 2. . . . said that I was only guessing and that I could not accuse Mrs. Chin of any wrong doing. I bring this out to show that this woman is protected by every level in the GVN Customs Service." (183)

Although almost every functionary in the customs service receives payoffs from the smugglers, U.S. customs advisers believe that Chief Khoi's job is the most financially rewarding. While most division chiefs only receive payoffs from their immediate underlings, his enforcement powers enable him to receive kickbacks from every division of the customs service. Since even so minor an official as the chief collections officer at Tan Son Nhut cargo warehouse kicked back $22,000 a month to his superiors, Chief Khoi's income must have been enormous. (184)

In early 1971 U.S. customs advisers mounted a "strenuous effort" to have the deputy chief transferred, but Chief Khoi was extremely adept at protecting his associate. In March American officials in Vientiane learned that Rep. Pham Chi Thien would be boarding a flight for Saigon carrying four kilos of heroin and relayed the information to Saigon. When U.S. customs advisers asked the Fraud Repression Division to make the arrest (U.S. customs officials have no right to make arrests), Chief Khoi entrusted the seizure to his opium-smoking assistant. The "hero" was later decorated for this "accomplishment," and U.S. customs advisers, who were still trying to get him fired, or at least transferred, had to grit their teeth and attend a banquet in his honor. (185)

Frustrated by months of inaction by the U.S. mission and outright duplicity from the Vietnamese, members of the U.S. customs advisory team evidently decided to take their case to the American public. Copies of the unflattering customs advisory reports quoted above were leaked to the press and became the basis of an article that appeared on the front page of The New York Times on April 22, 1971, under the headline, "Saigon Airport a Smuggler's Paradise." (186)

The American response was immediate. Washington dispatched more customs advisers for duty at Tan Son Nhut, and the U.S. Embassy finally demanded action from the Thieu regime. Initially, however, the Saigon government was cool to the Embassy's demands for a cleanup of the customs' Fraud Repression Division. It was not until the smuggling issue became a political football between the Khiem and Thieu factions that the Vietnamese showed any interest in dealing with the problem.