1. Sicily: Home of the Mafia

| Books - The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia |

Drug Abuse

1. Sicily: Home of the Mafia

AT THE END of World War II, there was an excellent chance that heroin addiction could be eliminated in the United States. The wartime security measures designed to prevent infiltration of foreign spies and sabotage to naval installations made smuggling into the United States virtually impossible. Most American addicts were forced to break their habits during the war, and consumer demand just about disappeared. Moreover, the international narcotics syndicates were weakened by the war and could have been decimated with a minimum of police effort. (1)

During the 1930s most of America's heroin had come from China's refineries centered in Shanghai and Tientsin. This was supplemented by the smaller amounts produced in Marseille by the Corsican syndicates and in the Middle East by the notorious Eliopoulos brothers. Mediterranean shipping routes were disrupted by submarine warfare during the war, and the Japanese invasion of China interrupted the flow of shipments to the United States from the Shanghai and Tientsin heroin laboratories. The last major wartime seizure took place in 1940, when forty-two kilograms of Shanghai heroin were discovered in San Francisco. During the war only tiny quantities of heroin were confiscated, and laboratory analysis by federal officials showed that its quality was constantly declining; by the end of the war most heroin was a crude Mexican product, less than 3 percent pure. And a surprisingly high percentage of the samples were fake.' As has already been mentioned, most addicts were forced to undergo an involuntary withdrawal from heroin, and at the end of the war the Federal Bureau of Narcotics reported that there were only 20,000 addicts in all of America. (2)

After the war, Chinese traffickers had barely reestablished their heroin labs when Mao Tse-tung's peasant armies captured Shanghai and drove them out of China. (3) The Eliopoulos brothers had retired from the trade with the advent of the war, and a postwar narcotics indictment in New York served to discourage any thoughts they may have had of returning to it. (4) The hold of the Corsican syndicates in Marseille was weakened, since their most powerful leaders had made the tactical error of collaborating with the Nazi Gestapo, and so were either dead or in exile. Most significantly, Sicily's Mafia had been smashed almost beyond repair by two decades of Mussolini's police repression. It was barely holding onto its control of local protection money from farmers and shepherds. (5)

With American consumer demand reduced to its lowest point in fifty years and the international syndicates in disarray, the U.S. government had a unique opportunity to eliminate heroin addiction as a major American social problem. However, instead of delivering the death blow to these criminal syndicates, the U.S. government-through the Central Intelligence Agency and its wartime predecessor, the OSS-created a situation that made it possible for the SicilianAmerican Mafia and the Corsican underworld to revive the international narcotics traffic.(6)

In Sicily the OSS initially allied with the Mafia to assist the Allied forces in their 1943 invasion. Later, the alliance was maintained in order to check the growing strength of the Italian Communist party on the island. In Marseille the CIA joined forces with the Corsican underworld to break the hold of the Communist Party over city government and to end two dock strikes--one in 1947 and the other in 1950-that threatened efficient operation of the Marshall Plan and the First Indochina War. (7) Once the United States released the Mafia's corporate genius, Lucky Luciano, as a reward for his wartime services, the international drug trafficking syndicates were back in business within an alarmingly short period of time. And their biggest customer? The United States, the richest nation in the world, the only one of the great powers that had come through the horrors of World War II relatively untouched, and the country that bad the biggest potential for narcotics distribution. For, in spite of their forced withdrawal during the war years, America's addicts could easily be won back to their heroin persuasion. For America itself had long had a drug problem, one that dated back to the nineteenth century.

Addiction in America: The Root of the Problem

Long before opium and heroin addiction became a law enforcement problem, it was a major cause for social concern in the United States. By the late 1800s Americans were taking opium-based drugs with the same alarming frequency as they now consume tranquilizers, pain killers, and diet pills. Even popular children's medicines were frequently opium based. When heroin was introduced into the United States by the German pharmaceutical company, Bayer, in 1898, it was, as has already been mentioned, declared nonaddictive, and was widely prescribed in hospitals and by private practitioners as a safe substitute for morphine. After opium smoking was outlawed in the United States ten years later, many opium addicts turned to heroin as a legal substitute, and America's heroin problem was born,

By the beginning of World War I the most conservative estimate of America's addict population was 200,000, and growing alarm over the uncontrolled use of narcotics resulted in the first attempts at control. In 1914 Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Act. It turned out to be a rather ambiguous statute, requiring only the registration of all those handling opium and coca products and establishing a stamp tax of one cent an ounce on these drugs. A medical doctor was allowed to prescribe opium, morphine, or heroin to a patient, "in the course of his professional practice only." The law, combined with public awareness of the plight of returning World War I veterans who had become addicted to medical morphine, resulted in the opening of hundreds of public drug maintenance clinics. Most clinics tried to cure the addict by gradually reducing his intake of heroin and morphine. However, in 1923 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in United States vs. Behrman, that the Harrison Act made it illegal for a medical doctor to prescribe morphine or heroin to an addict under any circumstances. The clinics shut their doors and a new figure appeared on the American scene-the pusher.

The Mafia in America

At first the American Mafia ignored this new business opportunity. Steeped in the traditions of the Sicilian "honored society," which absolutely forbade involvement in either narcotics or prostitution, the Mafia left the heroin business to the powerful Jewish gangsters-such as "Legs" Diamond, "Dutch" Schultz, and Meyer Lansky-who dominated organized crime in the 1920s. The Mafia contented itself with the substantial profits to be gained from controlling the bootleg liquor industry.(8)However, in 1930-1931, only seven years after heroin was legally banned, a war erupted in the Mafia ranks. Out of the violence that left more than sixty gangsters dead came a new generation of leaders with little respect for the traditional code of honor."

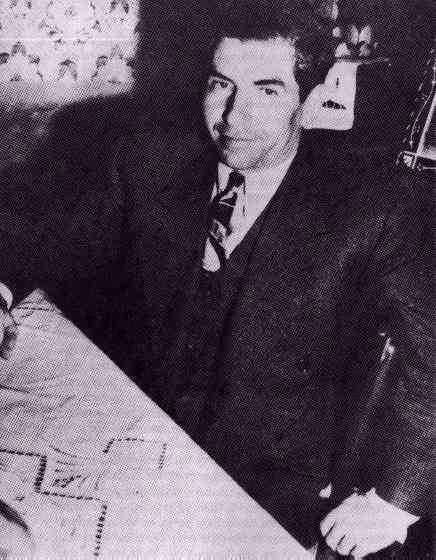

Image: Salvatore Lucania, alias Lucky Luciano.

The leader of this mafioso youth movement was the legendary Salvatore C. Luciana, known to the world as Charles "Lucky" Luciano. Charming and strikingly handsome, Luciano must rank as one of the most brilliant criminal executives of the modern age. For, at a series of meetings shortly following the last of the bloodbaths that completely eliminated the old guard, Luciano outlined his plans for a modern, nationwide crime cartel. His modernization scheme quickly won total support from the leaders of America's twenty-four Mafia "families," and within a few months the National Commission was functioning smoothly. This was an event of historic proportions: almost singlehandedly, Luciano built the Mafia into the most powerful criminal syndicate in the United States and pioneered organizational techniques that are still the basis of organized crime today. Luciano also forged an alliance between the Mafia and Meyer Lansky's Jewish gangs that has survived for almost 40 years and even today is the dominant characteristic of organized crime in the United States.

With the end of Prohibition in sight, Luciano made the decision to take the Mafia into the lucrative prostitution and heroin rackets. This decision was determined more by financial considerations than anything else. The predominance of the Mafia over its Jewish and Irish rivals had been built on its success in illegal distilling and rumrunning. Its continued preeminence, which Luciano hoped to maintain through superior organization, could only be sustained by developing new sources of income.

Heroin was an attractive substitute because its relatively recent prohibition had left a large market that could be exploited and expanded easily. Although heroin addicts in no way compared with drinkers in numbers, heroin profits could be just as substantial: heroin's light weight made it less expensive to smuggle than liquor, and its relatively limited number of sources made it more easy to monopolize.

Heroin, moreover, complemented Luciano's other new business venture-the organization of prostitution on an unprecedented scale. Luciano forced many small-time pimps out of business as he found that addicting his prostitute labor force to heroin kept them quiescent, steady workers, with a habit to support and only one way to gain enough money to support it. This combination of organized prostitution and drug addiction, which later became so commonplace, was Luciano's trademark in the 1930s. By 1935 he controlled 200 New York City brothels with twelve hundred prostitutes, providing him with an estimated income of more than $10 million a year. (9) Supplemented by growing profits from gambling and the labor movement (gangsters seemed to find a good deal of work as strikebreakers during the depression years of the 1930s) as well, organized crime was once again on a secure financial footing.

But in the late 1930s the American Mafia fell on hard times. Federal and state investigators launched a major crackdown on organized crime that produced one spectacular narcotics conviction and forced a number of powerful mafiosi to flee the country. In 1936 Thomas Dewey's organized crime investigators indicted Luciano himself on sixty-two counts of forced prostitution. Although the Federal Bureau of Narcotics had gathered enough evidence on Luciano's involvement in the drug traffic to indict him on a narcotics charge, both the bureau and Dewey's investigators felt that the forced prostitution charge would be more likely to offend public sensibilities and secure a conviction. They were right. While Luciano's modernization of the profession had resulted in greater profits, he had lost control over his employees, and three of his prostitutes testified against him. The New York courts awarded him a thirtyto fifty-year jail term.(10)

Luciano's arrest and conviction was a major setback for organized crime: it removed the underworld's most influential mediator from active leadership and probably represented a severe psychological shock for lower-ranking gangsters.

However, the Mafia suffered even more severe shocks on the mother island of Sicily. Although Dewey's reputation as a "racket-busting" district attorney was rewarded by a governorship and later by a presidential nomination, his efforts seem feeble indeed compared to Mussolini's personal vendetta against the Sicilian Mafia. During a state visit to a small town in western Sicily in 1924, the Italian dictator offended a local Mafia boss by treating him with the same condescension he usually reserved for minor municipal officials. The mafioso made the foolish mistake of retaliating by emptying the piazza of everyone but twenty beggars during Mussolini's speech to the "assembled populace."(11) Upon his return to Rome, the outraged Mussolini appeared before the Fascist parliament and declared total war on the Mafia. Cesare Mori was appointed prefect of Palermo and for two years conducted a reign of terror in western Sicily that surpassed even the Holy Inquisition. Combining traditional torture with the most modern innovations, Mori secured confessions and long prison sentences for thousands of mafiosi and succeeded in reducing the venerable society to its weakest state in a hundred years."(12) Although the campaign ended officially in 1927 as Mori accepted the accolades of the Fascist parliament, local Fascist officials continued to harass the Mafia. By the beginning of World War II, the Mafia had been driven out of the cities and was surviving only in the mountain areas of western Sicily.(13)

The Mafia Restored: Fighters for Democracy in World War II

World War II gave the Mafia a new lease on life. In the United States, the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) became increasingly concerned over a series of sabotage incidents on the New York waterfront, which culminated with the burning of the French liner Normandie on the eve of its christening as an Allied troop ship.

Powerless to infiltrate the waterfront itself, the ONI very practically decided to fight fire with fire, and contacted Joseph Lanza, Mafia boss of the East Side docks, who agreed to organize effective antisabotage surveillance throughout his waterfront territory. When ONT decided to expand "Operation Underworld" to the West Side docks in 1943 they discovered they would have to deal with the man who controlled them: Lucky Luciano, unhappily languishing in the harsh Dannemora prison. After he promised full cooperation to naval intelligence officers, Luciano was rewarded by being transferred to a less austere state penitentiary near Albany, where he was regularly visited by military officers and underworld leaders such as Meyer Lansky (who had emerged as Luciano's chief assistant).(14)

While ONI enabled Luciano to resume active leadership of American organized crime, the Allied invasion of Italy returned the Sicilian Mafia to power.

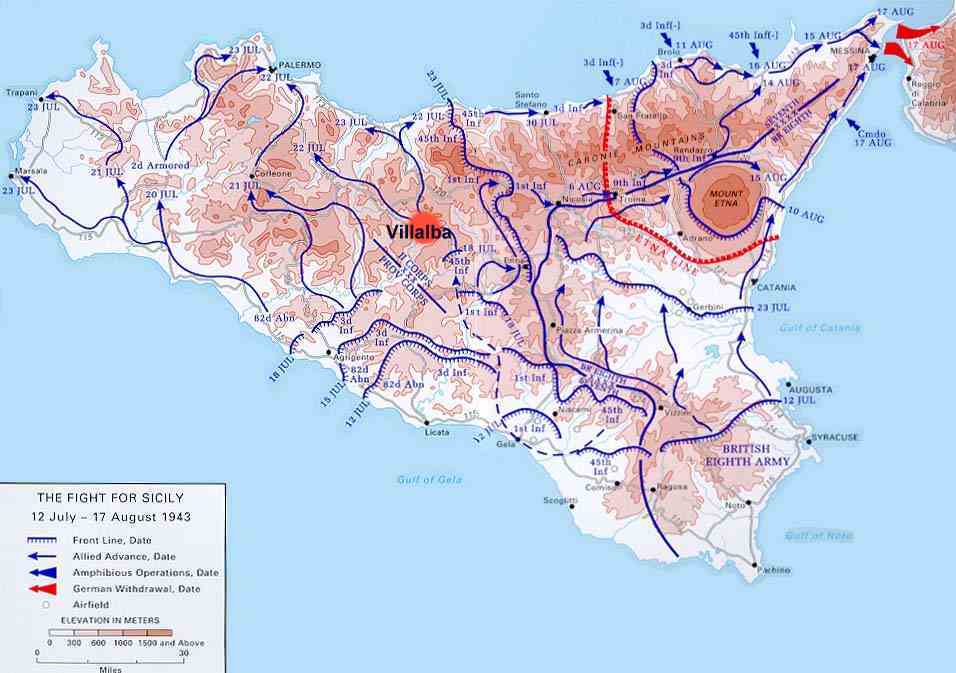

On the night of July 9, 1943, 160,000 Allied troops landed on the extreme southwestern shore of Sicily.(15) After securing a beachhead, Gen. George Patton's U.S. Seventh Army launched an offensive into the island's western hills, Italy's Mafialand, and headed for the city of Palermo.(16) Although there were over sixty thousand Italian troops and a hundred miles of boobytrapped roads between Patton and Palermo, his troops covered the distance in a remarkable four days.(17)

The Defense Department has never offered any explanation for the remarkable lack of resistance in Patton's race through western Sicily and pointedly refused to provide any information to Sen. Estes Kefauver's Organized Crime Subcommittee in 1951.(18) However, Italian experts on the Sicilian Mafia have never been so reticent.

Five days after the Allies landed in Sicily an American fighter plane flew over the village of Villalba, about forty-five miles north of General Patton's beachhead on the road to Palermo, and jettisoned a canvas sack addressed to "Zu Calo." "Zu Calo," better known as Don Calogero Vizzini, was the unchallenged leader of the Sicilian Mafia and lord of the mountain region through which the American army would be passing. The sack contained a yellow silk scarf emblazoned with a large black L. The L, of course, stood for Lucky Luciano, and silk scarves were a common form of identification used by mafiosi traveling from Sicily to America.(19)

It was hardly surprising that Lucky Luciano should be communicating with Don Calogero under such circumstances; Luciano had been born less than fifteen miles from Villalba in Lercara Fridi, where his mafiosi relatives still worked for Don Calogero.(20) Two days later, three American tanks rolled into Villalba after driving thirty miles through enemy territory. Don Calogero climbed aboard and spent the next six days traveling through western Sicily organizing support for the advancing American troops. (21) As General Patton's Third Division moved onward into Don Calogero's mountain domain, the signs of its dependence on Mafia support were obvious to the local population. The Mafia protected the roads from snipers, arranged enthusiastic welcomes for the advancing troops, and provided guides through the confusing mountain terrain.(22)

While the role of the Mafia is little more than a historical footnote to the Allied conquest of Sicily, its cooperation with the American military occupation (AMGOT) was extremely important. Although there is room for speculation about Luciano's precise role in the invasion, there can be little doubt about the relationship between the Mafia and the American military occupation.

This alliance developed when, in the summer of 1943, the Allied occupation's primary concern was to release as many of their troops as possible from garrison duties on the island so they could be used in the offensive through southern Italy. Practicality was the order of the day, and in October the Pentagon advised occupation officers "that the carabinieri and Italian Army will be found satisfactory for local security purposes. (23) But the Fascist army had long since deserted, and Don Calogero's Mafia seemed far more reliable at guaranteeing public order than Mussolini's powerless carabinieri. So, in July the Civil Affairs Control Office of the U.S. army appointed Don Calogero mayor of Villalba. In addition, ANIGOT appointed loyal mafiosi as mayors in many of the towns and villages in western Sicily. (24)

As Allied forces crawled north through the Italian mainland, American intelligence officers became increasingly upset about the leftward drift of Italian politics. Between late 1943 and mid 1944, the Italian Communist party's membership had doubled, and in the German-occupied northern half of the country an extremely radical resistance movement was gathering strength; in the winter of 1944, over 500,000 Turin workers shut the factories for eight days despite brutal Gestapo repression, and the Italian underground grew to almost 150,000 armed men. Rather than being heartened by the underground's growing strength, the U.S. army became increasingly concerned about its radical politics and began to cut back its arms drops to the resistance in mid 1944. (25) "More than twenty years ago," Allied military commanders reported in 1944, "a similar situation provoked the March on Rome and gave birth to Fascism. We must make up our minds-and that quickly-whether we want this second march developing into another 'ism.' (26)

In Sicily the decision had already been made. To combat expected Communist gains, occupation authorities used Mafia officials in the AMGOT administration. Since any changes in the island's feudal social structure would cost the Mafia money and power, the "honored society" was a natural anti-Communist ally. So confident was Don Calogero of his importance to AMGOT that he killed Villalba's overly inquisitive police chief to free himself of all restraints. (27) In Naples, one of Luciano's lieutenants, Vito Genovese, was appointed to a position of interpreterliaison officer in American army headquarters and quickly became one of AMGOT's most trusted employees. It was a remarkable turnabout; less than a year before, Genovese had arranged the murder of Carlo Tresca, editor of an anti-Fascist Italian-language newspaper in New York, to please the Mussolini government. (28)

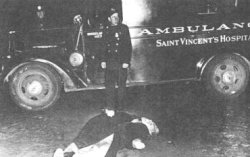

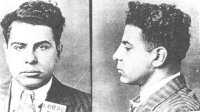

Images: Carlo Tresca (left). Carlo Tresa dead on the street (Archives of Labor Urban Affairs, Wayne State University) (center). Carmine Galante (UPI Bettman) (rigth)Carlo Tresca (1879-1943), was born in Italy in 1879. After being active in the Italian Railroad Workers' Federation, Tresca moved to the United States in 1904. Elected secretary of the Italian Socialist Federation of North America and a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), he took part in strikes of Pennsylvania coal miners before becoming involved in the important industrial disputes in Lawrence and Paterson. Tresca, who lived with Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, was editor of the anti-fascist newspaper, Il Martello (The Hammer) for over 20 years. Carlo Tresco was leader of the Anti-Fascist Alliance and was assassinated in New York City in 1943. Many of Tresca's comrades believed that his murder had been ordered by Generoso Pope, the ex-fascist publisher of Il Progresso Italo-Americano, as Tresca had attacked him relentlessly throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. One plausible theory said that Tresca was killed at the order of an Italian underworld figure named Frank Garofalo, identified as a member of the Mafia. Another theory said that Carmine Galante was the man who undoubtedly killed him. Galante was to become one of the most significant figures in a criminal group that has operated in New York, and beyond, for seventy years. On that dark, miserable January night when he gunned down his target, the probable killer Galante was already associated with or indeed possibly a member of a Mafia organization that is known today as the Bonanno Crime Family. ()

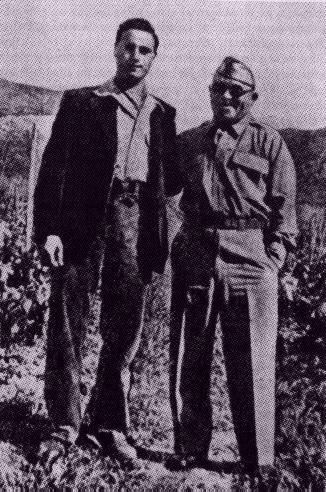

Image: Vito Genovese (rigth) with Salvatore Giuliano (left). Genovese was Colonel Poletti's driver, interpreter and consiglieri (adviser).

Genovese and Don Calogero were old friends, and they used their official positions to establish one of the largest black market operations in all of southern Italy. Don Calogero sent enormous truck caravans loaded with all the basic food commodities necessary for the Italian diet rolling northward to hungry Naples, where their cargoes were distributed by Genovese's organization (29) All of the trucks were issued passes and export papers by the AMGOT administration in Naples and Sicily, and some corrupt American army officers even made contributions of gasoline and trucks to the operation.

In exchange for these favors, Don Calogero became one of the major supporters of the Sicilian Independence Movement, which was enjoying the covert support of the OSS. As Italy veered to the left in 1943-1944, the American military became alarmed about their future position in Italy and felt that the island's naval bases and strategic location in the Mediterranean might provide a possible future counterbalance to a Communist mainland. (30) Don Calogero supported this separatist movement by recruiting most of western Sicily's mountain bandits for its volunteer army, but quietly abandoned it shortly after the OSS dropped it in 1945.

Don Calogero rendered other services to the anti-Communist effort by breaking up leftist political rallies. On September 16, 1944, for example, the Communist leader Girolama Li Causi held a rally in Villalba that ended abruptly in a hail of gunfire as Don Calogero's men fired into the crowd and wounded nineteen spectators. (31) Michele Pantaleone, who observed the Mafia's revival in his native village of Villalba, described the consequences of AMGOT's occupation policies:

By the beginning of the Second World War, the Mafia was restricted to a few isolated and scattered groups and could have been completely wiped out if the social problems of the island had been dealt with . . . the Allied occupation and the subsequent slow restoration of democracy reinstated the Mafia with its full powers, put it once more on the way to becoming a political force, and returned to the Onorata Societa the weapons which Fascism had snatched from it.(32)

Luciano Organizes the Postwar Heroin Trade

In 1946 American military intelligence made one final gift to the Mafia -they released Luciano from prison and deported him to Italy, thereby freeing the greatest criminal talent of his generation to rebuild the heroin trade. Appealing to the New York State Parole Board in 1945 for his immediate release, Luciano's lawyers based their case on his wartime services to the navy and army. Although naval intelligence officers called to give evidence at the hearings were extremely vague about what they had promised Luciano in exchange for his services, one naval officer wrote a number of confidential letters on Luciano's behalf that were instrumental in securing his release. (33) Within two years after Luciano returned to Italy, the U.S. government deported over one hundred more mafiosi as well. And with the cooperation of his old friend, Don Calogero, and the help of many of his old followers from New York, Luciano was able to build an awesome international narcotics syndicate soon after his arrival in Italy.(34)

The narcotics syndicate Luciano organized after World War It remains one of the most remarkable in the history of the traffic. For more than a decade it moved morphine base from the Middle East to Europe, transformed it into heroin, and then exported it in substantial quantities to the United States-all without ever suffering a major arrest or seizure. The organization's comprehensive distribution network within the United States increased the number of active addicts from an estimated 20,000 at the close of the war to 60,000 in 1952 and to 150,000 by 1965.

After resurrecting the narcotics traffic, Luciano's first problem was securing a reliable supply of heroin. Initially he relied on diverting legally produced heroin from one of Italy's most respected pharmaceutical companies, Schiaparelli. However, investigations by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Narcotics in 1950-which disclosed that a minimum of 700 kilos of heroin had been diverted to Luciano over a four-year period-led to a tightening of Italian pharmaceutical regulations. (35) But by this time Luciano had built up a network of clandestine laboratories in Sicily and Marseille and no longer needed to divert the Schiaparelli product.

Morphine base was now the necessary commodity. Thanks to his contacts in the Middle East, Luciano established a long-term business relationship with a Lebanese who was quickly becoming known as the Middle East's major exporter of morphine base-Sami El Khoury. Through judicious use of bribes and his high social standing in Beirut society, (36) El Khoury established an organization of unparalleled political strength. The directors of Beirut Airport, Lebanese customs, the Lebanese narcotics police, and perhaps most importantly, the chief of the antisubversive section of the Lebanese police, (37) protected the import of raw opium from Turkey's Anatolian plateau into Lebanon, its processing into morphine base, and its final export to the laboratories in Sicily and Marseille. (38)

After the morphine left Lebanon, its first stop was the bays and inlets of Sicily's western coast. There Palermo's fishing trawlers would meet ocean-going freighters from the Middle East in international waters, pick up the drug cargo, and then smuggle it into fishing villages scattered along the rugged coastline. (39)

Once the morphine base was safely ashore, it was transformed into heroin in one of Luciano's clandestine laboratories. Typical of these was the candy factory opened in Palermo in 1949: it was ]eased to one of Luciano's cousins and managed by Don Calogero himself.(40) The laboratory operated without incident until April 11, 1954, when the Roman daily Avanti! published a photograph of the factory under the headline "Textiles and Sweets on the Drug Route." That evening the factory was closed, and the laboratory's chemists were reportedly smuggled out of the country. (41)

Once heroin had been manufactured and packaged for export, Luciano used his Mafia connections to send it through a maze of international routes to the United States. Not all of the mafiosi deported from the United States stayed in Sicily. To reduce the chance of seizure, Luciano had placed many of them in such European cities as Milan, Hamburg, Paris, and Marseille so they could forward the heroin to the United States after it arrived from Sicil concealed in fruits, vegetables, or candy. From Europe heroin was shipped directly to New York or smuggled through Canada and Cuba. (42)

While Luciano's prestige and organizational genius were an invaluable asset, a large part of his success was due to his ability to pick reliable subordinates. After he was deported from the United States in 1946, he charged his long-time associate, Meyer Lansky, with the responsibility for managing his financial empire. Lansky also played a key role in organizing Luciano's heroin syndicate: he supervised smuggling operations, negotiated with Corsican heroin manufacturers, and managed the collection and concealment of the enormous profits. Lansky's control over the Caribbean and his relationship with the Florida-based Trafficante family were of particular importance, since many of the heroin shipments passed through Cuba or Florida on their way to America's urban markets. For almost twenty years the Luciano-Lansky-Trafficante troika remained a major feature of the international heroin traffic.(43)

Organized crime was welcome in prerevolutionary Cuba, and Havana was probably the most important transit point for Luciano's European heroin shipments. The leaders of Luciano's heroin syndicate were at home in the Cuban capital, and regarded it as a "safe" city: Lansky owned most of the city's casinos, and the Trafficante family served as Lansky's resident managers in Havana. (44)

Luciano's 1947 visit to Cuba laid the groundwork for Havana's subsequent role in international narcotics-smuggling traffic. Arriving in January, Luciano summoned the leaders of American organized crime, including Meyer Lansky, to Havana for a meeting, and began paying extravagant bribes to prominent Cuban officials as well. The director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics at the time felt that Luciano's presence in Cuba was an ominous sign.

I had received a preliminary report through a Spanish-speaking agent I had sent to Havana, and I read this to the Cuban Ambassador. The report stated that Luciano had already become friendly with a number of high Cuban officials through the lavish use of expensive gifts. Luciano had developed a full-fledged plan which envisioned the Caribbean as his center of operations . . . Cuba was to be made the center of all inter national narcotic operations.(45)

Pressure from the United States finally resulted in the revocation of Luciano's residence visa and his return to Italy, but not before he bad received commitments from organized crime leaders in the United States to distribute the regular heroin -shipments he promised them from Europe. (46)

The Caribbean, on the whole, was a happy place for American racketeers-most governments were friendly and did not interfere with the "business ventures" that brought some badly needed capital into their generally poor countries. Organized crime had been well established in Havana long before Luciano's landmark voyage. During the 1930s Meyer Lansky "discovered" the Caribbean for northeastern syndicate bosses and invested their illegal profits in an assortment of lucrative gambling ventures. In 1933 Lansky moved into the Miami Beach area and took over most of the illegal off-track betting and a variety of hotels and casinos.(47) He was also reportedly responsible for organized crime's decision to declare Miami a "free city" (i.e., not subject to the usual rules of territorial monopoly). (48) Following his success in Miami Lansky moved to Havana for three years, and by the beginning of World War 11 he owned the Hotel Nacional's casino and was leasing the municipal racetrack from a reputable New York bank.

Burdened by the enormous scope and diversity of his holdings, Lansky had to delegate much of the responsibility for daily management to local gangsters. (49) One of Lansky's earliest associates in Florida was Santo Trafficante, Sr., a Sicilian-born Tampa gangster. Trafficante had earned his reputation as an effective organizer in the Tampa gambling rackets, and was already a figure of some stature when Lansky first arrived in Florida. By the time Lansky returned to New York in 1940, Trafficante had assumed responsibility for Lansky's interests in Havana and Miami.

By the early 1950s Traflicante had himself become such an important figure that he in turn delegated his Havana concessions to Santo Trafficante, Jr., the most talented of his six sons. Santo, Jr.'s, official position in Havana was that of manager of the Sans Souci Casino, but he was far more important than his title indicates. As his father's financial representative, and ultimately Meyer Lansky's, Santo, Jr., controlled much of Havana's tourist industry and became quite close to the pre-Castro dictator, Fulgencio Batista. (50) Moreover, it was reportedly his responsibility to receive the bulk shipments of heroin from Europe and forward them through Florida to New York and other major urban centers, where their distribution was assisted by local Mafia bosses.-(51)

The Marseille Connection

The basic Turkey-Italy-America heroin route continued to dominate the international heroin traffic for almost twenty years with only one important alteration-during the 1950s the Sicilian Mafia began to divest itself of the heroin manufacturing business and started relying on Marseille's Corsican syndicates for their drug supplies. There were two reasons for this change. As the diverted supplies of legally produced Schiaparelli heroin began to dry up in 1950 and 195 1, Luciano was faced with the alternative of expanding his own clandestine laboratories or seeking another source of supply. While the Sicilian mafiosi were capable international smugglers, they seemed to lack the ability to manage the clandestine laboratories. Almost from the beginning, illicit heroin production in Italy had been plagued by a series of arrests-due more to mafiosi incompetence than anything else-of couriers moving supplies in and out of laboratories. The implications were serious; if the seizures continued Luciano himself might eventually be arrested. (52)

Preferring to minimize the risks of direct involvement, Luciano apparently decided to shift his major source of supply to Marseille. There, Corsican syndicates had gained political power and control of the waterfront as a result of their involvement in CIA strikebreaking activities. Thus, Italy gradually declined in importance as a center for illicit drug manufacturing, and Marseille became the heroin capital of Europe.(53)

Although it is difficult to probe the inner workings of such a clandestine business under the best of circumstances, there is reason to believe that Meyer Lansky's 1949-1950 European tour was instrumental in promoting Marseille's heroin industry.

After crossing the Atlantic in a luxury liner, Lansky visited Luciano in Rome, where they discussed the narcotics trade. He then traveled to Zurich and contacted prominent Swiss bankers through John Pullman, an old friend from the rumrunning days. These negotiations established the financial labyrinth that organized crime still uses today to smuggle its enormous gambling and heroin profits out of the country into numbered Swiss bank accounts without attracting the notice of the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

Pullman was responsible for the European end of Lansky's financial operation: depositing, transferring, and investing the money once it arrived in Switzerland. He used regular Swiss banks for a number of years until the Lansky group purchased the Exchange and Investment Bank of Geneva, Switzerland. On the other side of the Atlantic, Lansky and other gangsters used two methods to transfer their money to Switzerland: "friendly banks" (those willing to protect their customers' identity) were used to make ordinary international bank transfers to Switzerland; and in cases when the money was too "hot" for even a friendly bank, it was stockpiled until a Swiss bank officer came to the United States on business and could "transfer" it simply by carrying it back to Switzerland in his luggage.(54) After leaving Switzerland, Lansky traveled through France, where he met with high-ranking Corsican syndicate leaders on the Riviera and in Paris. After lengthy discussions, Lansky and the Corsicans are reported to have arrived at some sort of agreement concerning the international heroin traffic.(55) Soon after Lansky returned to the United States, heroin laboratories began appearing in Marseille. On May 23, 1951, Marseille police broke into a clandestine heroin laboratory-the first to be uncov~ -ed in France since the end of the war. After discovering another on March 18, 1952, French authorities reported that "it seems that the installation of clandestine laboratories in France dated from 1951 and is a consequence of the cessation of diversions in Italy during the previous years. (56) During the next five months French police uncovered two more clandestine laboratories. In future years U.S. narcotics experts were to estimate that the majority of America's heroin supply was being manufactured in Marseille.

1 Sicily: Home of the Mafia

1. J. M. Scott, The White Poppy (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1969), pp. 167-169. ![]()

2. United Nations, Economic and Social Council, World Trends of the Illicit Traffic During the War 1939-1945 (E/CS 7/9, November 23, 1946),pp.10,14. ![]()

3. William P. Morgan, Triad Societies in Hong Kong (Hong Kong: Government Press, 1960), pp. 76-77. ![]()

4. Charles Siragusa, The Trail of the Poppy (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966), pp. 180-181. ![]()

5. David Arman, "The Mafia," in Norman MacKenzie, Secret Societies (New York: Collier Books, 1967), p. 213. ![]()

6. The CIA had its origins in the wartime Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which was formed to make sure that intelligence errors like Pearl Harbor did not happen again. The OSS was disbanded on September 20, 1945, and remained buried in the State Department, the army, and the navy until January 22, 1946, when President Truman formed the Central Intelligence Group. With the passage of the National Security Act in 1947 the group became an agency, and on September 18, 1947, the CIA was born (David Wise and Thomas B. Ross, The Invisible Government [New York: Random House, 1964], pp. 91-94). ![]()

7. U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Government Operations, Organized Crime and Illicit Traffic in Narcotics, 88th Cong., lst and 2ndsess., 1964, pt. 4, p. 913. 1![]()

8. Nicholas Gage, "Mafioso's Memoirs Support Valachi's Testimony About Crime Syndicate," in The New York Times, April 11, 197 1. ![]()

9. Harry J. Anslinger, The Protectors (New York: Farrar, Straus and Company, 1964), p. 74. ![]()

11. Norman Lewis, The Honored Society (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1964), pp. 72-73. ![]()

13. Michele Pantaleone, The Mafia and Politics (London: Chatto & Windus, 1966), p. 52. ![]()

14. Gay Talese, Honor Thy Father (New York: World Publishing, 1971), pp. 212213. ![]()

15. R. Ernest Dupuy, Col. U.S.A. Ret., World War II: A Compact History (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1969), pp. 147-148. ![]()

16. Lt. Col. Albert N. Garland and Howard McGraw Smith, United States Army in World War II. The Mediterranean Theater of Operations. Sicily and the Surrender of Italy (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1965), p. 244. ![]()

18. Estes Kefauver, Crime in America, quoted in Lewis, The Honored Society, pp. 1819. ![]()

19. Pantaleone, The Mafia and Politics, pp. 54-55. Michele Pantaleone is probably Italy's leading authority on the Sicilian Mafia. He himself is a native and long time resident of Villalba, and so is in a unique position to know what happened in the village between July 15 and July 21, 1943. Also, many of Villalba's residents testified in the Sicilian press that they witnessed the fighter plane incident and the arrival of the American tanks several days later (Lewis, The Honored Society, P. 19). ![]()

20. Talese, Honor Thy Father, p. 201. ![]()

21. Pantaleone, The Mafia and Politics, p. 56. ![]()

23. Gabriel Kolko, The Politics of War (New York: Random House 1968), p. 57.

24. Pantaleone, The Mafia and Politics, p. 58. ![]()

25. Kolko, The Politics of War, p. 48. ![]()

26. U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States (pt. 3, p. 1114), quoted in Kolko, The Politics of War, p. 55. ![]()

27. Lewis, The Honored Society, p. 107. ![]()

28. Talese, Honor Thy Father, p. 214. ![]()

29. Pantaleone, The Mafia and Politics, p. 63. ![]()

30. Lewis, The Honored Society, pp. 146, 173. ![]()

31. Pantaleone, The Mafia and Politics, p. 88. ![]()

33. Lewis, The Honored Society, p. 18, ![]()

34. Siragusa, The Trail of the Poppy, p. 83. ![]()

36. U.S. Congress, Senate Subcommittee on Improvements in the Federal Criminal Code, Committee of the Judiciary, Illicit Narcotics Traffic, 84th Cong., Ist sess., 1955, p. 99. ![]()

37. Official correspondence of Michael G. Picini, Federal Bureau of Narcotics, to agent Dennis Doyle, August 1963. Picini and Doyle were discussing whether or not to use Sami El Khoury as an informant now that he had been released from prison. The authors were permitted to read the correspondence at the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, Washington, D.C., October 14, 1971. ![]()

38. Interview with an agent, U.S. Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, Washington, D.C., October 26, 1971. ![]()

39. Danilo Dolci, Report from Palermo (New York: The Viking Press, 1970), pp. 118-120. ![]()

40. Pantaleone, The Mafia and Politics, p. 188. ![]()

42. Interview with an agent, U.S. Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, Washington, D.C., October 14, 1971. ![]()

44. Interview with an agent, U.S. Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, New Haven, Connecticut, November 18, 1971. ![]()

45. Harry J. Anslinger, The Murderers (New York: Farrar, Straus and Company, 1961), p. 106. (Emphasis added.) ![]()

46. Hank Messick, Lansky (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1971), p. 137. ![]()

50. Ed Reid, The Grim Reapers (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1969), pp. 9092. ![]()

51. Interview with an agent, U.S. Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, Washington, D.C., October 14, 1971.![]()

52. Senate Committee on Government Operations, Organized Crime and Illicit Traffic in Narcotics, 88th Cong., Ist and 2nd sess., pt. 4, p. 891.![]()

54. The New York Times, December 1, 1969, p. 42.![]()

55. Messick, Lansky, pp. 169-170.![]()

56. United Nations, Department of Social Affairs, Bulletin on Narcotics 5, no. 2, (April-June 1953), 48. (Emphasis added.)![]()

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|