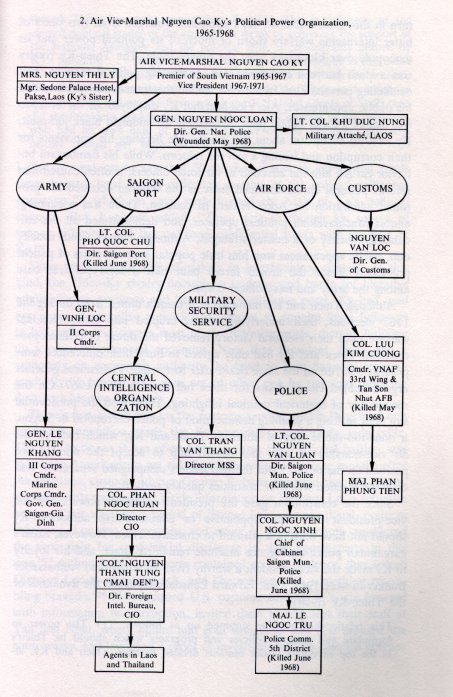

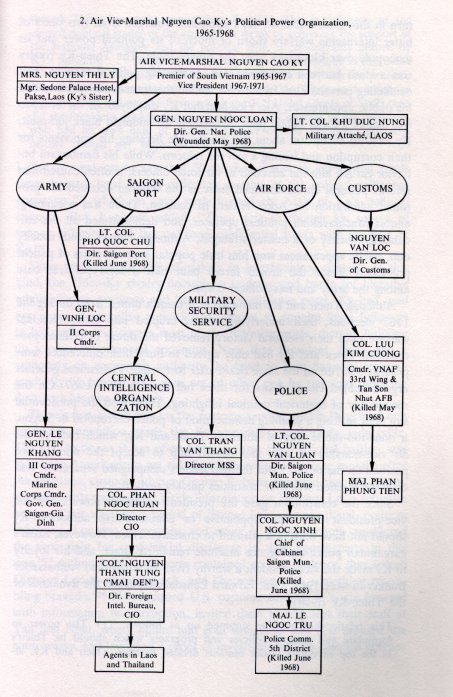

Politics

built Premier Ky's powerful syndicate, and politics weakened it. His meteoric

political rise had enabled his power broker, General Loan, to take control of

the police-intelligence bureaucracy and use its burgeoning resources to increase

their revenue from the lucrative rackets -which in Saigon always includes the

flourishing narcotics trade. However, in 1967 simmering animosity between

Premier Ky and Gen. Nguyen Van Thieu, then head of Saigon's military junta,

broke into open political warfare. Outmaneuvered by this calculating rival at

every turn in this heated

conflict, Ky's apparatus emerged from two years of bitter internecine warfare

shorn of much of its political power and its monopoly over kickbacks from the

opium trade. The Thieu-Ky rivalry was a clash between ambitious men, competing

political factions, and conflicting personalities. In both his behind-the-scenes

machinations and his public appearances, Air ViceMarshal Ky displayed all the

bravado and flair of a cocky fighter pilot. Arrayed in his midnight black

jumpsuit, Ky liked to barnstorm about the countryside berating his opponents for

their corruption and issuing a call for reforms. While his flamboyant behavior

earned him the affection of air force officers, it often caused him serious

political embarrassment, such as the time he declared his profound admiration

for Adolf Hitler. In contrast, Thieu was a cunning, almost Machiavellian

political operator, and demonstrated all the calculating sobriety of a master

strategist. Although Thieu's tepid, usually dull, public appearances won him

little popular support, years of patient politicking inside the armed forces

built him a solid political base among the army and navy officer

corps.

Although Thieu and Ky managed to present a united front during the 1967 elections, their underlying enmity erupted into bitter factional warfare once their electoral victory removed the threat of civilian government. Thieu and Ky had only agreed to bury their differences temporarily and run on the same ticket after forty-eight Vietnamese generals argued behind closed doors for three full days in June 1967. On the second day of hysterical political infighting, Thieu won the presidential slot after making a scathing denunciation of police corruption in Saigon, a none-too-subtle way of attacking Loan and Ky, which reduced the air vice-marshal to tears and caused him to accept the number-two position on the ticket. (75) But the two leaders campaigned separately, and once the election was over hostilities quickly revived.

Since the constitution gave the president enormous powers and the vicepresident very little appointive or administrative authority, Ky should not have been in a position to challenge Thieu. However, Loan's gargantuan policeintelligence machine remained intact, and his loyalty to Ky made the vicepresident a worthy rival. In a report to Ambassador Bunker in May 1968, Gen. Edward Lansdale explained the dynamics of the Thieu-Ky rivalry:

"This relationship may be summed Lip as follows: ( I ) The power to formulate and execute policies and programs which should be Thieu's as the top executive leader remains divided between Thieu and Ky, athough Thieu has more power than Ky. (2) Thieu's influence as the elected political leader of the country, in terms of achieving the support of the National Assembly and the political elite, is considerably limited by Ky's influence . . . (Suppose, for example, a U.S. President in the midst of a major war had as Vice President a leader who had been the previous President, who controlled the FBI, CIA, and DIA [Defense Intelligence Agency], who had more influence with the JCS [Joint Chiefs of Staff] than did the President, who had as much influence in Congress as the President, who had his own base of political support outside Congress, and who neither trusted nor respected the President.)" (76)

Lansdale went on to say that "Loan has access to substantial funds through extra legal money-collecting systems of the police /intelligence apparatus," (77) which, in large part, formed the basis of Ky's political strength. But, Lansdale added, "Thieu acts as though his source of money is limited and has not used confidential funds with the flair of Ky. (78)

Since money is the key to victory in interfactional contests of this kind, the Thieu-Ky rivalry became an underground battle for lucrative administrative positions and key police-intelligence posts. Ky had used two years of executive authority as premier to appoint loyal followers to high office and corner most of the lucrative posts, thereby building up a powerful financial apparatus. Now that President Thieu had a monopoly on appointive authority, he tried to gain financial strength gradually by forcing Ky's men out of office one by one and replacing them with his own followers.

Thieu's first attack was on the customs service, where Director Loc's notorious reputation made the Ky apparatus particularly vulnerable. The first tactic, as it has often been in these interfactional battles, was to use the Americans to get rid of an opponent. Only three months after the elections, customs adviser George Roberts reported that his American assistants were getting inside information on Director Loc's activities because "this was also a period of intense inter-organizational, political infighting. Loc was vulnerable, and many of his lieutenants considered the time right for confidential disclosure to their counterparts in this unit." (79) Although the disclosures contained no real evidence, they forced Director Loc to counterattack, and "he reacted with something resembling bravado." (80) He requested U.S. customs advisers to come forward with information on corruption, invited them to augment their staff at Tan Son Nhut, where opium and gold smuggling had first aroused the controversy, and launched a series of investigations into customs corruption. When President Thieu's new minister of finance had taken office, he had passed the word that Director Loc was on the way out. But Loc met with the minister, pointed out all of his excellent anticorruption work, and insisted on staying in office. But then, as Roberts reported to Washington, Thieu's faction delivered the final blow:

"Now, to absolutely assure Loc's destruction, his enemies have turned to the local press, giving them the same information they had earlier given to this unit. The press, making liberal use of innuendo and implication, had presented a series of front page articles on corruption in Customs. They are a strong indictment of Director Loc."(81)

Several weeks later Loc was fired from his job (82) and the way was open for the Thieu faction to take control over the traffic at Tan Son Nhut Airport.

The Thieu and Ky factions were digging in for all-out war, and it seemed that these scandals would continue for months, or even years. However, on January 31, 1968, the NLF and the North Vietnamese army launched the Tet offensive and 67,000 troops attacked 102 towns and cities across South Vietnam, including Saigon itself. The intense fighting, which continued inside the cities for several months, disrupted politics asusual while the government dropped everything to drive the NLF back into the rice paddies. But not only did the Tet fighting reduce much of Saigon-Cholon to rubble, it decimated the ranks of Vice-President Ky's trusted financial cadres and crippled his political machine. In less than one month of fighting during the "second wave" of the Tet offensive, no less than nine of his key fund raisers were killed or wounded.

General Loan himself was seriously wounded on May 5 while charging down a blind alley after a surrounded NLF soldier. An AK-47 bullet severed the main artery in his right leg and he was forced to resign from command of the police to undergo surgery and months of hospitalization. (83) The next day Col. Luu Kim Cuong, commander of the air force transport wing and an important figure in Ky's network, was shot and killed while on operations on the outskirts of Saigon. (84)

While these two

incidents would have been enough to seriously weaken Ky's apparatus, the

mysterious incident that followed a month later dealt a crippling blow. On the

afternoon of June 2, 1968, a coterie of Ky's prominent followers were meeting,

for reasons never satisfactorily explained, in a command post in Cholon. At

about 6:00 P.M. a U.S. helicopter, prowling the skies above the ravaged

Chinese quarter on the lookout for NLF units, attacked the building, rocketing and strafing it. Among

the dead were: Lt. Col. Pho Quoc Chu; director of the Saigon port authority and Ky's brother-in-law. Lt. Col. Dao Ba Phuoc, commander of the 5th Rangers, which were assigned to the Capital Military District. Lt. Col. Nguyen Van Luan, director of the

Saigon Municipal Police. Major Le Ngoc Tru, General Loan's right-hand man and police commissioner of the fifth

district. Major Nguyen Bao Thuy, special assistant to the mayor of Saigon. Moreover, General Loan's brother-in-law, Lt. Col. Van Van Cua, the mayor of Saigon, suffered a shattered arm and resigned to undergo four

months of hospitalization. (85)

These represented

the financial foundation of Ky's political machine, and once they were gone his

apparatus began to crumble. As vicepresident, Ky had no authority to appoint

anyone to office, and all of the nine posts vacated by these casualties, with

the exception of the air force transport command, were given to Thieu's men. On

June 6 a loyal Thieu follower, Col, Tran Van Hai, was appointed director-general

of the National Police and immediately began a rigorous purge of all of Loan's

men in the lower echelons. (86)

The Saigon press reported that 150 secret police

had been fired and a number of these had also been arrested.

(87)On June 15 Colonel Hai delivered a decisive blow to

Ky's control over the police by dismissing eight out of Saigon's eleven district

police commissioners. (88) As Ky's apparatus

weakened, his political fortunes went into a tailspin: loss of minor district

and municipal police posts meant he could not collect protection money from

ordinary businesses or from the rackets; as the "extra legal money-collecting

systems of the police/intelligence apparatus" began to run dry, he could no

longer counter President Thieu's legal appointive power with gifts; and once the

opposition weakened, President Thieu began to fire many high-ranking pro-Ky

police-intelligence officials. (89) While the quiet

desertion of the ant-army bureaucracy to the Thieu machine was almost

imperceptible to outside observers, the desertion of Ky's supporters in the

National Assembly's cash-and-carry lower house was scandalously obvious. Shortly

after the October 1967 parliamentary elections were over and the National

Assembly convened for the first time since the downfall of Diem, the Thieu and Ky machines

had begun competing for support in the lower house.

(90) Using money provided by

General Loan, Ky had purchased a large bloc of forty-two deputies, the

Democratic Bloc, which included Buddhists, southern intellectuals, and even a

few hill tribesmen. Since Thieu lacked Ky's "confidential funds," he had allied

himself with a small twenty-one-man bloc, the Independence Bloc, comprised

mainly of right-wing Catholics from northern and central Vietnam.

(91) Both men

were paying each of their deputies illegal supplemental salaries of $4,000 to

$6,000 a year, in addition to bribes ranging up to $1,800 on every important

ballot. (92)

At a minimum it must have been costing Ky $15,000 to $20,000 a month

just to keep his deputies on the payroll, not to mention outlays of over

$100,000 for the particularly critical showdown votes that came along once or

twice a year. In May 1968 General Lansdale reported to Ambassador Bunker that

"Thieu's efforts . . . to create a base of support in both Houses have been made

difficult by Ky's influence among some important senators . . . and Ky's

influence over the Democratic Bloc in the Lower House."

(93) However, throughout

the summer of 1968 Ky's financial difficulties forced him to cut back the

payroll, and representatives began drifting away from his bloc. As Thieu's financial

position strengthened throughout the summer, his assistant in charge of

relations with the National Assembly approached a number of deputies and

reportedly offered them from $1,260 to $2,540 to join a new proThieu faction

called the People's Progress Bloc. One deputy explained that "in the last few

months, the activities of the lower house have become less and less productive

because a large number of deputies have formed a bloc for personal interests

instead of political credits." In September The Washington Post reported:

"The "Democratic Bloc," loyal

to Vice President Ky, now retains 25 out of its 42 members. Thieu and Ky have been privately at odds

since 1966. Thieu's ascendancy over his only potential rival has grown

substantively in recent months.

The severe blow dealt to

the Ky bloc in the House has not been mentioned extensively in the local press

except in the daily Xay Dung (To Construct), which is a Catholic, pro-Ky

paper." (94) These realignments in

the balance of political power had an impact on the opium traffic. Despite his

precipitous political decline, Air ViceMarshal Ky retained control over the air

force, particularly the transport wing. Recently, the air force's transport wing

has been identified as one of the most active participants in South Vietnam's heroin smuggling (see pages

187-188). Gen. Tran Thien Khiem, minister of the interior (who was to emerge as

a major faction leader himself when he became prime minister in September 1969)

and a nominal Thieu supporter, inherited control of Saigon's police apparatus,

Tan Son Nhut customs, and the Saigon port authority. However, these noteworthy

internal adjustments were soon dwarfed in importance by two dramatic

developments in South Vietnam's narcotics trafficthe increase in heroin and

morphine base exports destined for the American market and the heroin epidemic

among American GIs serving in South Vietnam.