|

THE MARIHUANA CONSENSUS had collapsed completely by the end of 1970. That use of the drug had so easily been translated into a political symbol assured that no substitute would be quickly achieved. Some thoughtful observers saw no prospect of improvement until American society came to grips with the fundamental social and philosophical issues regarding consumption of all psychoactive substances. Others contended that social necessity would itself dictate substantial changes in marihuana policy, whether or not fundamental issues were confronted and whether or not a replacement consensus was achieved. In this view the politics would continue to dominate the rhetoric, but institutional imperatives would dictate policy.

Under the former view objective fact-finding was an essential predicate to rational policy-making, and so long as ideological factors interfered with the scientific process, policy-making would continue to be chaotic. Under the latter view, fact-finding Was irrelevant to outcome, although it might continue to be the lightning rod for political dialogue.

Either view is consistent with the evolution of the marihuana issue during 1971-72. The fact-finding process continued to be politically charged; indeed, the pressure for authoritative scientific determinations had made the very selection of the fact-finder an important political issue.

Who Should Be the Fact-Finder?

From the outset of congressional consideration of drug control in the late 1960s, the marihuana discussion did not center on appropriate penalties—almost every witness agreed that penalties should be reduced but not eliminated; instead, attention was generally focused on how and when the government ought to issue a defini-tive report on the scientific and public policy issues involved. About the same time that the administration introduced the Controlled Dangerous Substances Act, legislators of both parties introduced legislation in both houses to establish a presidential commission on marihuana. Spearheading the movement in the House was Congressman Koch of New York, who garnered 60 co-sponsors for his bill, which was joined in the hopper by four others. Senator Moss introduced a companion measure in the Senate.'

The lot of the presidential commission had not been a happy one during the 1960s. Reports issued by commissions on crime (Katzenbach, 1967), civil disorders (Kerner, 1968), violence (Eisenhower, 1969), campus unrest (Scranton, 1970), and pornography (Lockhart, 1970) burdened library shelves, testifying collectively to the political limits of enlightenment. Despite this poor record, many legislators considered the marihuana issue a matter of some urgency and sought an intensive investigation covering all aspects of the problem. They felt further that if the report were to be credible and authoritative, the issuing body would have to be independent, wearing the "mantle of a Presidential Commission with all that suggests and recommends."2

The administration was not in such a hurry. It is no accident that the commission approach, sponsored most enthusiastically by legislators of liberal persuasion, was viewed skeptically by an administration that had staked out a conservative position on the drug issue. Marihuana had by now become a political issue on which the liberals were committed to change. In such circumstances "expert" commissions often function as expedient detours, post-poning direct confrontation; yet, because expert panels tend to be drawn from the intellectual class, their recommendations frequently coincide with liberal ideology. Thus, Congressman Koch and his colleagues had good reason to seek commission fact-finding, and the Nixon Administration had equally good reason to be suspicious of this approach.

Beyond the political dimension, divergent views on the appropriate fact-finder also stemmed from disparate views concerning which facts were being sought. Each side propounded the need to establish the facts as a predicate for rational decision-making. But each side was also aware that the fact-finder would make significant decisions simply by selecting which facts were important. Thus, advocates of change, including the sponsors of the commission legislation, were anxious for an authoritative body to explode specific myths—crime, addiction, insanity, death, progression to other drugs—and had no doubt that an objective study would aid their cause. The defenders, on the other hand, were looking for more generalized findings—that marihuana was a "dangerous drug," that it was a public health concern, and that its use could have adverse consequences for both the user and society.

Newsweek, for example, reported in September 1970 that Attorney General Mitchell hoped that "a national study commission on marihuana (similar to the Surgeon General's investigation of smoking)" will turn up sufficient negative evidence about mari-huana's effects "to allow youth to resist peer pressure to use the drug. It can be a dangerous and damaging drug... . I think we'll find physical and chemical evidence of that." For example, Mitchell reportedly continued, "a commission could make clear the distinc-tion between addiction—I think most everyone agrees this is not an addictive substance—and dependency. A kid gets into steady use of marihuana. After a while he gets less of a charge from it, and this psychological dependency causes him to move on to the harder stuff ... we have to get proof that it does create this dependency."3

Thus we see the critical importance of choosing the fact-finder. It was evident, in other words, that a fact-finder who wanted to whitewash marihuana could do so simply by saying what it does not do. On the other hand, a fact-finder looking for harm, as was the attorney general, could probably find it.

Another dimension of this conflict was officialdom's increasing discomfort with the medical-scientific orientation of the marihuana debate. Throughout the retrenchment period official spokesmen had submerged the philosophical, social, and legal issues, placing all their eggs in the health basket. Factors such as the drug's toxicity, acute effects, genetic effects, dependence liability, and long-term psychological and physiological effects had been officially assigned a pivotal role in the social and legal policy decision. As Mitchell's comments suggest, it was felt that at least in some of these areas research would indict marihuana as a "dangerous" drug, and that would be the end of it. In some respects the challengers themselves had abetted this response. They could have presented philosophical and social arguments more persuasively than could the government, but they generally failed to do so during the re-trenchment period. Instead, they often aided the government's case by contending that marihuana was "harmless."

By the end of the decade the debate was beginning to change direction. The harmless/dangerous charade was joined by more fundamental issues. The challengers relied more and more on philosophical and social arguments, and officialdom, having become uneasy with the medical orientation, was also turning to a socio-cultural defense. When asked what his position would be if a study were to "come out favorably for marihuana," the attorney general responded: "Why should we use it when it has no redeeming value? The desire of someone to get out of this world by puffing on mari-huana has no redeeming value. There is no rhyme or reason to it."4 In addition to such normative considerations, government authori-ties now recognized that a prohibitory policy was best premised on speculation about the adverse impact on the public health if marihuana use were to become widespread. Such considerations, difficult to convey in the first instance, would be impossible to resurrect in the aftermath of headlines such as "Pot Relatively Harmless" or "Occasional Use of Pot Harmless." Thus, the adminis-tration, wanted a fact-finder it could rely upon to concentrate on the long-term social impact of marihuana use.

Another objection to the commission approach, maintained vociferously within NIMH, was that definitive answers—even from the medical orientation—could not be provided in one or two years. Studies of the effects of long-term use had never been conducted and were just being fielded. A commission, according to this view, would have to emphasize the unknown and therefore could not provide a definitive report; and if it did not emphasize the unknown, the nation might suffer irreversible damage, as the tobacco experi-ence illustrated. Congressman Beister of Pennsylvania expressed the danger: "My apprehension is [that] we may explore the unknown with a target date of one year with a small group of people and achieve a resolution which pretends to say there is no longer an unknown when in point of fact there may continue to be a great one." 5

Congressman Beister and others were worried about the "human factor in the equation." That same "special impact" sought by the commission's proponents might cause incalculable social damage if the commission were incorrect or imprudent. It would offer "a fresh retreat for those who choose to use marihuana, saying that this does not hurt."6

Politicians were being pressed for answers. Some thought they knew what the answers would be and wanted to establish them in a credible way; others thought they also knew but preferred not to hear them. But the vast majority of politicians and certainly the general public were confused. Contradictions about specific drug effects abounded in reported research and official statements, and this uncertainty had been aggravated from 1965 to 1968 when most official medical spokesmen had maintained a judicious silence. In this connection Congressman Claude Pepper chastized the surgeon general in September 1969, noting that "one of the especi-ally alarming and confusing aspects of this entire controversy is the fact that the relevant agencies of our Federal Government have generally remained silent in the face of a most heated debate." Recalling that Dr. Goddard and Dr. Roger Egeberg, assistant secretary of HEW for Health and Scientific Affairs, had expr'essed personal, nonofficial views that "the criminal laws relating to marihuana are unrealistic and unenforcible," Pepper accused the execu-tive branch of taking "an ostrich-like approach to the problem, [being] more inclined to ignore the issues than to discuss them."7

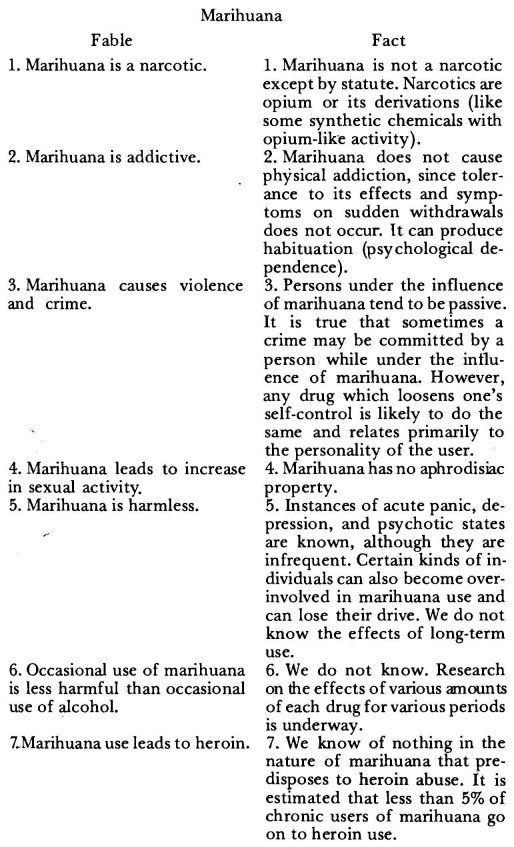

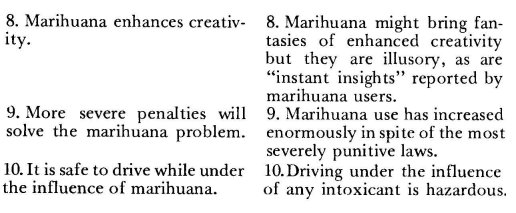

By the fall of 1969 the government's top medical spokesrnen had broken their official silence. Drs. Egeberg, Stanley Yolles (Director of NIMH), and Jesse Steinfeld (soon to become surgeon general) each noted the mythology surrounding marihuana and the disutility of the existing law. Dr. Yolles was most outspoken: "I know of no clearer instance in which the punishment for an in-fraction of the law is more harmful than the crime itself.. .. To equate [marihuana's] risk—either to the individual or society—with the risks inherent in the use of hard narcotics is—on the face of it—merely an effort to defend the indefensible, established position that has no scientific basis."8 Dr. Yolles then read the following chart:

Despite such candor, political restraints were still apparent. In contrast to their rhetoric, none of these physicians recommended a public policy more drastic than reduction of penalties. (In fact, Dr. Yolles had apparently broken the ranks; his strong position on marihuana penalties reportedly earned him a dismissal.) 9

The government physicians also opposed creation of a commis-sion. Dr. Yolles insisted that "there are some things we already know about marihuana in spite of the fact that many people are not willing to accept the knowledge."10 Instead of establishing another commission, he argued, Congress should "direct NIMH to conduct research and make a basic determination on mari-huana."ll Senator Dodd included such a mandate in his bill.

But Congressman Koch and his colleagues did not think this.was sufficient. "There is already feeling," he said, "that the inter-governmental agencies have not told the truth."12 Recognizing that studies must often be evaluated and reconciled, commission proponents such as Congressman Gude of Maryland insisted on the independence of a body "that is not answerable to the Executive or committed to a political position. .. . I don't think you can achieve this independence with an interdepartmental study."13

The administration finally succumbed to the pressure for an expert panel, but proposed that it be appointed jointly by the attorney general and the secretary of HEW instead of by the presi-dent. John Ingersoll, director of BNDD, was pressed hard by the House Judiciary Subcommittee members to explain why. He could not do so to their satisfaction. Undoubtedly, the administration was seeking lower visibility, increased control, and greater flexi-bility in appointments.

Interestingly enough, one witness was suspicious of the political controls attaching to presidential appointees as well. Rutgers Uni-versity's Dr. Helen Nowlis, who was later prevailed upon to head drug abuse education programs for the Office of Education, was afraid the president would select "a lot of law enforcement people

...[who] will not face the critical issues."14 To decrease political pressure, she would have diffused the appointing authority; but having come "reluctantly . . . to the conclusion that commissions tend to be more political than scientific or expert," she would have dispensed with the idea altogether; instead she would have decriminalized possession of marihuana immediately."

Congress ultimately diffused fact-finding responsibility. First, it enacted the "Marihuana and Health Reporting Act" in July 1970 mandating HEW to report annually on the health consequences of marihuana use.16 Several months later the House version of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act provided for a bipartisan National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse to be composed of thirteen members, nine to be appointed by the president and four by the Congress. The commission was to spend' the first year of its two-year life on marihuana only. The Senate accepted this provision.17

The federal government would speak with many voices, but it would speak at last.

The Politics of Fact-Finding

The designation of public fact-finders did not depoliticize the marihuana issue. In fact, initiation of a fact-finding process may have tightened the political screw. For example, the commission's independence was brought into question immediately after its appointment in early 1971.

President Nixon's selections were not greeted kindly by advo-cates of reform. "Its average age is 'an old 54; " one commentator noted. "The only pair of sideburns are snowy white, the youngest member is a 37-year-old cop, (Mitchell Ware, then superintendent of the Illinois Bureau of Investigation), and its second youngest, 40-year-old Mrs. Joan Ganz Cooney (executive producer) of Sesame Street' is in touch with a clientele somewhat below pot-blowing age."18 The commission's medical experts, Drs. Dana Farnsworth, Maurice Seevers, Henry Brill, and Thomas Ungerleider were attacked for their deep AMA "establishment" roots and for holding firm preconceived notions. The independence of the commission's chair-man, former Pennsylvania Governor Raymond Shafer, and of SMU Law School Dean Charles O. Galvin was questioned on the ground that federal judgeships might hang in the balance of commission deliberations.19 A Midwest educator, President John Howard of Rockford College, rounded out the presidential appointees. Finally, the commission's staff director Michael Sonnenreich—formerly deputy chief counsel of BNDD and leading protagonist of the Controlled Substances Act—was accused of being an administration tool." This was a "stacked deck" in the eyes of the reformers.

The president himself got into the act at a May Day 1971 press conference six weeks after the commission began its work. In answer to a questioner who pointed out that his own White House Conference on Youth had voted to legalize marihuana, the presi-dent replied: "As you know, there is a Commission that is supposed to make recommendations to me about this subject, and in this instance, however, I have such strong views that I will express them. I am against legalizing marihuana. Even if the Commission does recommend that it be legalized, I will not follow that recom-mendation."21

Some weeks later the president elaborated on the reason for his "strong feelings" when, in the context of a discussion of heroin addiction, he noted the need for

a massive program of information for the American people with regard to how the drug habit begins and how we eventually end up with so many being addicted to heroin. .. .

In that respect, that is one of the reasons I have taken such a strong position with regard to the question of marihuana. I realize this is controversial. But I can see no social or moral justification whatever for legalizing marihuana. I think it would be exactly the wrong step. It would simply encourage more and more of our young people to start down the long, dismal road that leads to hard drugs and eventually self-destruction.22

After these remarks, which received considerable attention in the press, the commission chairman defensively contended that the president had expressed a "personal opinion," and that the commission in no way felt bound by it.23 Some commentators were not so kind to President Nixon. Joseph Kraft, for exaxnple, accused the president of "trying to enhance his own popularity by taking a stand against unpopular habits practiced by an unpopular group," and urged him to "rise above the battles of domestic politics," "keep an open mind and wait for more information from the Marihuana Commission."24 Hedging their bets on the likely out-come of the commission's deliberations, the proponents of change used the president's statement to impugn the panel's credibility, thereby laying the groundwork for later undercutting any unfavor-able commission findings or recommendations.

For the six years during which the marihuana controversy had raged, truth was a highly subjective commodity. Science was but a means to an ideological end, as each research study was publicized immediately by the researchers themselves or by the combatants in the rhetorical struggle. Pending authoritative, objective fact-finding, this development reached a crescendo in May 19 7 1.

On 19 April the American Medical Association issued to the press advance copies of a forthcoming Journal article by two Philatielphia psychiatrists, Harold Kolansky and William Moore, entitled "Effects of Marihuana on Adolescents and Young Adults." Accompanying the article was an editorial sigh of relief reflected in the following AMA statement: "The attached paper . . . presents the first real evidence based on good research of the harmful effects of marihuana. Heretofore, medicine has been able to say only that there was no good evidence of harm from smoking pot. Now we , have some evidence." 25 The Kolansky-Moore conclusions then appeared prominently in national news magazines, on network news programs, and in newspapers throughout the country.26

The response was immediate and predictable. One criminal court judge in Miami, Florida, reportedly stated that he was now satisfied that marihuana had been proven harmful, and accordingly he would no longer be lenient with the drug's users; henceforth, mari-huana offenders would all go to jail. 27 Since their article was of considerable interest to policy makers, the Marihuana Commission invited the two doctors to testify at public hearings to be held in May.28 And advocates of legalization scurried about furiously to prepare a suitable rebuttal before the subversive "findings" could settle into the public consciousness.

Drs. Kolansky and Moore described thirty-eight patients, ages thirteen to twenty-four, whom they had seen in the course of their private practice between 1965 and 1970. These individuals, who all used marihuana moderately to heavily but had not used other illicit drugs, "showed an onset of psychiatric problems shortly after the beginning of marihuana smoking; these individuals had either no premorbid psychiatric history or had premorbid psychiatric symptoms which were extremely mild or almost unnoticeable in contrast to the serious symptomatology which followed the known onset of marihuana smoking."29

Having stipulated that the patients were normal prior to mari-huana use, the authors concluded that the "serious psychological effects," including apathy, confusion, and passivity, shown by all patients had been caused by their marihuana use: "Our study showed no evidence of a predisposition to mental illness in these patients prior to the development of psychopathologic symptoms once moderate-to-heavy use of cannabis derivations had begun. It is our impression that our study demonstrates the pôssibility that moderate-to-heavy use of marihuana in adolescents and young people without predisposition to psychiatric illness may lead,to ego decompensation ranging from mild ego disturbance to psychosis."39

These findings had been widely publicized, and Drs. Kolansky and Moore testified that they had received hundreds of letters from practicing psychiatrists reporting similar clinical observations and confirming their conclusions. Yet, the authors had not anticipated the criticism to which they would be subjected by virtue of having deposited their controversial views in the public forum.

Drs. Kolansky and Moore were accused by fellow psychiatrists of publicity-seeking, bias and preconception, methodological naivete, and insufficient experience in the area of psychoactive drugs.Not once, however, did their colleagues question the authors' clinical observations. This is an extremely important point. Kolansky and Moore had anticipated criticism because their conclusions were based on clinical experience rather than controlled laboratory experimentation. In fact, they were so conscious of this possibility that they reversed the argument: "We are aware that claims are made that large numbers of adolescents and young adults smoke marihuana regularly without developing symptoms or changes in academic study, but since these claims are made without the necessary accompaniment of thorough psychiatric study of each individual, they remain unsupported by scientific evidence."31

Challenging neither the clinical method nor the authors' observa-tions, an impressive array of experts unanimously dismissed the conclUsions drawn from these observations. Of course, objectivity in drawing hypothesis from experience—whether clinical or experi-mental—had always been the casualty in the marihuana controversy. The Kolansky-Moore incident epitomized this issue.

Psychiatric experts in the drug field unanimously concluded that their Philadelphia colleagues had shown only an association between marihuana-smoking and mental illness, not a causal relationship. No less an authority than Dr. Bertram Brown, who succeeded Stanley Yolles as director of NIMH, noted in testimony before the Marihuana Commission:

I must say that we must always be cautious about any one study and the implications drawn from such a study, a point we've made over and over again.

More specifically, let me make a rather fundamental point. .. ? Let us assume that "X" study—not the one you are going to hear—showed that 50 people who smoked marihuana had an acute psychotic paranoid breakdown with homicidal tendencies. Let's assume that for a moment, the worst possible outcome.

I think if you are dealing with a university or a population sample of a million or 10 million or 4 million, you can find 30 or 46 of anything.

I hasten to say, for example, that if you look carefully, you might find 30 or 40 college students who graduate Phi Beta Kappa, summa cum laude, who use marihuana three or four times a week for their four years. But nobody goes looking for that particular phenomenon.

And the reason I make that point is to show how any one study must be seen in the context of the total problem, from an epidemiological or sample point of view.32

A professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Solomon Snyder, 33 observed that

[all] Drs. Kolansky and Moore have shown is that some mari-huana users have mental illness. From their study it is not at all possible to ascribe a cause and effect relationship.

I do not know whether or not the heavy use of marihuana can lead to emotional disturbance. However, it is quite clear that the type of case report study reported by Drs. Kolansky and Moore is not capable of providing the information that would enable one to draw any conclusion as to the dangers of marihuana.34

Other commentators, whose own opinions about marihuana prohibition were on record, tried to account for the authors' obliviousness to methodology. Joel Fort, one of the earliest pro-ponents of marihuana reform,35 was most outspoken:

No drug, whether aspirin, alcohol, or marihuana is harmless or affects everyone in the same way; and a pathological frame of reference (traditionally applied by doctors and particularly psychiatrists) as opposed to a normative or naturalistic one can make any phenomenon including intercourse, a tennis match, or drinking alcohol seem sick or abnormal. One-dimensional view-ing with alarm out of context is anunfortunately common human behavior widely practiced by politicians, ambitious physicians, and others seeking instant headlines and rescue from often well-deserved obscurity. I could write the scenario on marihuana for the next decade; a damaged chromosome here, a psychotic reaction there, impotency, violence, promiscuity, dropping out; and less often, inherent pleasure, aphrodisia, health, and harm-lessness. A review of the available biographical and publitations data (about Kolansky and Moore) combined with their own statements in the article in question show that they are both in their late 40s, practice child psychoanalysis in affluent suburbs, have never worked in the field of mind-altering drugs, took five years to collect the small sample of 38 "patients" (19 each) reported on in the article, saw them one or two times`(pre-sumably for fifty minutes) without any previous or future contact, and have as their previous "scientific" publications: "Treatment of a three year old girl's severe infantile neurosis" and "Bee sting in the case of a ten year old boy in analysis."36

Dr. Norman Zinberg, who conducted some of the first controlled experimental studies on the acute effects of marihuana in man,37 was more subtle:

Each case begins by saying that the patients began by smoking marijuana and then moved on to homosexuality, enormous promiscuity, paranoid psychoses, delusions and so on, without further question as to causal relationship. There is no effort in this article to describe how marijuana brings these changes about. When Drs. Kolansky and Moore move into more specific psycho-logical terms, they talk in terms of severe decompensation of the ego. How does marijuana bring that about? They do not describe any spedfic mechanisms although they continue to state in several places in the article that this severe decompensa-tion of the ego is the direct result of the "toxic" effect of cannabis. Further, there is considerable confusion in this article between the neurological and the psychological. It is hard for me to imagine that if marijuana were toxic per se to any specific part of the nervous system including the brain, we would not see frequent reports of neurological disturbances with 12 to 20 million regular smokers.38

Finally, Dr. Lester Grinspoon, whose Marzjuana Reconsidered39 was published earlier in 1971, placed Kolansky and Moore in a wider perspective:

All in all this paper is, from a scientific point of view, so un-sound as to be all but meaningless. Unfortunately, from a social point of view it will have great significance in that it confirms for those people who have a hyperemotional bias against mari-juana all the things that they would like to believe happen as a consequence of the use of marijuana and in turn it will enlarge the credibility gap which exists between young people and the medical profession. I am convinced that if the American Medical Association were less interested in the imposition of a moral hegemony with respect to this issue and more concerned with the scientific aspects of this drug this paper would not have been accepted for publication.°

Ideological factors undoubtedly influenced the Kolansky-Moore interpretations of their data. Suggesting that clinicians as a class may be especially susceptible to "ideological selection of certain classes of facts," sociologist Erich Goode has carefully documented the traces of bias and "overt moralism" which Kolansky and Moore in particular wove "throughout a supposedly detached clinical study." In Goode's view, "it is only because the authors . . . accept the common sense and taken-for-granted assumption that marijuana is harmful that their case descriptions are believed to be meaningful. To accept the validity of their data as demonstrating the medical pathology of marijuana use, it would be necessary to believe in these conclusions beforehand. To an unbiased observer, all they demonstrate are the prejudices of Kolansky and Moore." 41

Perhaps shell-shocked by the vehemence of these criticisms of the Kolansky-Moore article (and of itself as well), the editorial board of the Journal of the American Medical Association there-after published a full critique of the "study." 42

Fact-Finding at Last

The Kolansky-Moore episode ushered out the most unruly phase of marihuana prohibition. By the end of 1971 most of the facts were on the table; the medical experts, still cautious from the stand-point of social policy, had begun to speak up. Then the official governmental fact-finders simultaneously confirmed these facts in early 1972. NIMH issued its second annual Marihuana and Health Report43 in February, and the Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse issued its report— Marihuana: A Signal of Misunder-standing44—in March. These events did not de-fuse the political aspects of the marihuana issue, but as to science, at least, consensus had finally replaced conflict. The rhetoric now began to center on the underlying social issues.

Who Uses Marihuana and How Often?

The commission estimated that 24 million Americans had used marihuana at least once. The NIMH estimate was more cons'erva-tive—between 15 and 20 million. Both reports estimated that about half of these individuals had simply experimented with the drug out of curiosity and given it up. Another 40 percent of the "ever-users" continue to use the drug but on an intermittent basis—once a week or less—for recreational purposes. A small percentage of the more frequent users (about 2 percent of the ever-using population) use the drug more than once daily. (The commission's second report, in March 1973, reported that 26 million Americans had tried marihuana and that 13 million continued to use the drug.)

Both reports noted that use of the drug was continuing to in-crease, spreading to all socioeconomic and occupational groups, but emphasized that use was highly age-specific. Of all the ever-users, about half were in the sixteen to twenty-five age bracket. Both reports estimated that 44 percent of those persons currently in college or graduate school had used marihuana at least once.

Why Do People Smoke Marihuana?

Both reports dispelled the retrenchment stereotype of marihuana users as sick, emotionally maladjusted persons. Instead, both documents considered experimentation with and recreational use of the drug (thereby encompassing perhaps 90 percent of the ever-users) to be a social phenomenon. The NIMH report stated: "It is well recognized that marihuana use, like much other illegal drug use, occurs first in a social group, is supported by group norms, and functions as a shared social symbol. . . . The spread of marihuana through different segments of the society is aptly viewed as an example of adoption of an innovation. 45

The commission put it this way:

The most notable statement that can be made about the vast majority of marihuana users—experimenters and intermittent users—is that they are essentially indistinguishable from their non-marihuana using peers by any fundamental criterion other than their marihuana use. . . .

Experimentation with the drug is motivated primarily by curiosity and a desire to share a social experience. [E] xperi-menters are characteristically quite conventional and practically indistinguishable from the non-user in terms of life style, activities, social integration, and vocational or academic perfor-mance... .

The intermittent users are motivated to use marihuana for reasons similar to those of the experimenters. They use the drug irregularly and infrequently but generally continue to do so because of its socializing and recreational aspects.. . .

[For them] marihuana smoking is a social activity. 46

Both fact-finding bodies did suggest that the marihuana-using behavior of the heavy users is more likely to be symptomatic of underlying emotional difficulties, and that these individuals are most likely to be multi-drug users as well.

Acute Effects

As to the acute physical toxicity of marihuana, the commission found:

No conclusive evidence exists of any physical damage, distur-bances of bodily processes or proven human fatalities attributable solely to even very high doses of marihuana.

[Ml arihuana is 'a rather unexciting compound of negligible immediate toxicity at the doses usually consumed in this country.

Experiments with the drug in monkeys demonstrated that the dose required for overdose death was enormous and for all practical purposes unachievable by humans smoking marihuana. This is in marked contrast to other substances in common use, most notably alcohol and barbiturate sleeping pills.+7

The NIMH report noted that "acute toxic physical reactions to marihuana are relatively rare," and that "evidence from acute toxicity studies in animals and human case reports of overdose seems to indicate that the ratio of lethal dose to effective dose is quite large and is much more favorable than that of other common psychoactive drugs such as alcohol and barbiturates."48

With regard to acute mental effects, the commission stated:

The immediate effect of marihuana on normal mental pr6cesses is a subtle alteration in state of consciousness probably related to a change in short-term memory, mood, emotion and volition. This effect on the mind produces a varying influence on cogni-tive and psychomotor task performance which is highly individu-alized, as well as related to dosage, time, complexity of the task and experience of the user. The effect on personal, sociaf and vocational functions is difficult to predict. In most instances, the marihuana intoxication is pleasurable. In rare cases, the experi-ence may lead to unpleasant anxiety and panic, and in a predisposed few, to psychosis:49

The NIMH report echoed this finding:

It seems clear that marihuana use can precipitate certain less serious adverse reactions, such as simple depressive and panic reactions, particularly in inexperienced users. However, non-drug factors may be the most important determinants in these cases. In addition, there is some reason to believe that it may precipi-tate psychotic episodes in persons with a preexisting borderline personality or psychotic disorder. There is considerable similarity in clinical description between the "acute toxic psychoses" re-ported in the Eastern literature and the acute psychoses described in a number of Western reports. All seem to occur primarily after heavy usage which is greater than that to which the individual is accustomed. These psychoses have some characteristics of an acute brain syndrome. They seem to be self-limited and short-lived if the drug is removed. Some reports have described a more prolonged psychotic course after such an initial acute phase, but the possibility of other psychopathology in these cases has not been ruled out. 5°

Long-Term Effects

Both the Marihuana Commission and NIMH emphasized the paucity of research regarding the effects of long-term use of marihuana. Truly reliable findings would have to await controlled longitudinal studies with matched samples of long-term heavy users and non-users. The American experience is too recent to have deposited a sufficiently large population of long-term heavy users. Consequently, initial data must be gathered from studies of the heavy hashish-using populations in Jamaica, Greece, Afghanistan, and other cannabis-origin countries. Yet the vastly different standards of medical care and économic development in these countries make the data extremely difficult to evaluate in terms of cause and effect.

As to the long-term effects on the body of intermittent or moderate use (once a day or less), both reports found no disturbing evidence. The commission stated on the basis of an experimental study O'f Americans who had used the drug intermittently or moderately on an average of five years: "No significant physical, biochemical or mental abnormalities could be attributed solely to their marihuana smoking."51 NIMH concluded from "both Eastern and Western literature" that there was "little evidence at this time that light to moderate use of cannabis [over a long term] has deleterious physical effects. Almost all reports of physical harm from cannabis use are based on observations of moderate to heavy, chronic use of the drug." "

On the basis of preliminary findings from studies of long-term heavy hashish users in Greece and Jamaica, both reports indicated that nothing disturbing had yet appeared other than the chronic bronchitis and respiratory problems associated with heavy smoking of any substance. Mild liver injury and decrement of pulmonary lung function had been associated with heavy marihuana use in some studies, but no conclusions were justified. The Marihuana and Health Report warned in this connection, however, that

[t] he difficulty of proving a causal relationship between chronic use of any drug and a resulting illness should be kept in mind. Observation for many years is often necessary with heavy reliance on epidemiologic and statistical methods. The recent example of the role of cigarette smoking in certain illnesses illustrates many of the problems involved. For these reasons it is likely to take many years before the full story on possible physical effects from chronic use of marihuana will be complete. 53

As to the effect of long-term, heavy use on mental functioning, NIMH concluded that: "At the present time evidence that mari-huana is a sufficient or contributory cause of chronic psychosis is weak and rests primarily on temporal association. Further epidemi-ological and controlled clinical studies are necessary in order to clarify this important issue."54

The Marihuana Commission concluded from the Eastern data that:

The incidence of psychiatric hospitalizations for acute psychoses and of use of drugs other than alcohol is not significantly higher than among the non-using population. The existence of a specific long-lasting, cannabis-related psychosis is poorly defined. If heavy cannabis use produces a specific psychosis, it must be quite rare or else exceedingly difficult to distmguish from other acute or chronic psychoses.

Recent studies suggest that the occurrence of any form of psychosis in heavy cannabis users is no higher than in the general population. Although such use is often quite prevalent in hos-pitalized mental patients, the drug could only be considered a causal factor in a few cases. Most of these were short-term reactions or toxic overdoses. In addition, a concurrent use of alcohol often played a role in the episode causing hospitalization55.

In this connection, it is instructive to note the NIMH commen-tary on the Kolansky and Moore article:

In a widely publicized report, Kolansky and Moore described behavior problems, suicide attempts, sexual promiscuity and psychoses in 38 adolescent psychiatric patients who used mari-huana. They attributed all of these problems to marihuana use and on the basis of retrospective information felt that there was no evidence of prior psychopathology. This study illustrates the difficulty in interpretation of attempts to establish a causal role for marihuana using retrospective analysis, biased sampling, and ignoring the prevalance of psychopathology in a comparable population:56

Similarly, both reports noted some concern about the persistent suggestions in both Western and Eastern literature that marihuana use caused an "amotivational syndrome" involving lethargy, insta-bility, social and personal deterioration, and loss of interest in activities other than drug use. Nonetheless, both reports concluded that a causal relationship between heavy cannabis use and this syndrome had not been established. NIMH, for example, observed that:

The relevant question would seem to be whether or not the regular use of marihuana at a level below chronic intoxication may bring about personality changes through mechanisms other than the immediate pharmacological effects of the drug.

'Sociological factors add to the problems of interpretation since much drug use is associated with a youth counterculture which often rejects the more conventional orientation. The fact that heavy marihuana users may have a high incidence of pre-existing psychopathology raises the question of whether or not any,decreased interest and motivation observed in them may be a function of the psychopathological condition rather than of the drug. Therefore, the question of whether or not there exists a causal relationship between cannabis and an amotivational syndrome or only an associative relationship remains to be answered:57

Genetic Damage

Neither the commission nor NIMH found, in the commission's words, any "reliable evidence . .. that marihuana causes genetic defects in man.58

Dependence Liability

The two reports also agreed that marihuana use does not induce physical dependence and, in the commission's words, that "no torturous withdrawal syndrome follows the sudden cessation of chronic, heavy use."9 NIMH noted that Eastern studies have suggested a psychological dependence in heavy users, but that U.S. studies using much lower doses for shorter time periods had not found any such evidence1.60 The commission noted in this connec-tion that: "Although evidence indicates that heavy, long-term cannabis users may develop psychological dependence, even then the level of psychological dependence is no different from the syndrome of anxiety and restlessness seen when an American stops smoking tobacco cigarettes." 61

Progression to Other Drugs

Each report devoted many pages to the alleged causal relationship between marihuana use and use of other drugs, and each affirmed the clear correlation between increasing frequency of marihuana use and use of other illicit drugs. But both reports concludea that the relationship was definitely not a causal one, and that the over-whelming majority of marihuana users use no other illicit drug.

NIMH concluded: "While heavier marihuana use is clearly associ-ated with the use of other drugs as well—those who use it regularly are far more likely than nonusers to have experimented with other illicit drugs—there is no evidence that the drug itself "causes" such use. More frequent users are likely to find drug use appealing or to spend time with others who do so or in settings where other drugs are readily available.62

The commission meandered through the statistical maze sur-rounding the issue, noting:

If any one statement can characterize why persons in the United States escalate their drug use patterns and become polydrug users, it is peer pressure. Indeed, if any drug is associated with the use of other drugs, including marihuana, it is tobacco, followed closely by alcohol.

The overwhelming majority of marihuana users do not progress to other drugs. They either remain with marihuana or forsake its use in favor of alcohol. In addition, the largest number of mari-huana users in the United States today are experimenters or intermittent users, and 2% of those who have ever used it are presently heavy users. Only moderate and heavy use of marihuana is significantly associated with persistent use of other drugs.

Marihuana use per se does not dictate whether other drugs will be used; nor does it determine the rate of progression, if and when it occurs, or which drugs might be used.

Whether or not marihuana leads to other drug use depends on the individual, on the social and cultural setting in which the drug use takes place, and on the nature of the drug market.63

Crime

Both reports dismissed the crime thesis. NIMH equivocated a little: "There continues to be little evidence that marihuana use in itself causes criminal behavior. It is still questionable whether marihuana tends to loosen inhibitions and encourage immoral behavior, and whether marihuana tranquilizes users and thus deters violence." 64

The commission was quite direct:

The weight of the evidence is that marihuana does not cause violent or aggressive behavior; if anything, marihuana generally serves to inhibit the expression of such behavior. Marihuana-induced relaxation of inhibitions is not ordinarily accompanied by an exaggeration of aggressive tendencies.

In essence, neither informed current professional opinion nor empirical research, ranging from the 1930's to the present, has produced systematic evidence to support the thesis that mari-huana use, by itself, either invariably or generally leads to or causes crime, including acts of violence, juvenile delinquency or aggressive behavior. Instead the evidence suggests that sociolegal and the cultural variables account for the apparent statistical correlation between marihuana use and crime or delinquency."

What Do the Findings Mean?

The Marihuana Commission had been assigned a broader role than simply assessing the individual health consequences of marihuana use. To place this information in its wider social context, the commission generalized its findings for purposes of social policy. First and foremost, it concluded that marihuana use in contempor-ary American society is not a problem. "From what is known now about the effects of marihuana," the commission concluded, "its use at the present level does not constitute a major threat to public health." 66 This conclusion was based primarily on the fact that "there is little proven danger of physical or psychological harm from the experimental or intermittent use of the natural prepara-tions of cannabis."67 This, of course, includes 90 percent of those persons who have ever used the drug.

"The risk of harm," the commission continued, "lies instead in the heavy, long-term use of the drug, particularly of its more potent preparations." And that risk, of course, was itself of uncertain dimensions since the commission's major concern—the psychologi-cal consequences of long-term heavy use—remained speculative. Since the at-risk population is no more than half a million, at present, the public health orientation counsels a concern for prevention: "A significant increase in the at-risk population could convert what is now a minor public health concern in this country to one of major proportions." 68

The Dam Breaks: The Authorities Recommend a Change

Together, the Marihuana Commission Report and the HEW Report finally debunked the marihuana myths. Turning its attention to social and legal policy, the commission recommended that Ameri-can society adopt a policy of seeking to discourage marihuana use, while concentrating primarily on the prevention of heavy and very heavy use.69 With regard to the law, the commission urged that the criminal sanction be withdrawn from all private consumption-related activity, including possession for personal use and casual nonprofit distribution. As far as commercial activities were concerned, how-ever, the commission rejected a regulatory (alcohol model) approach, preferring instead to retain the prohibitory model. About the same time (February 1972), Dr. Bertram Brown, director of NIMH re-marked in a press conference attending release of the second Marihuana and Health Report that he, too, opposed "legalization" but favored "decriminalization" of marihuana use:7° In so doing, Dr. Brovvn maintained a stance he had first taken a year earlier—one which was a bit more liberal than that espoused by his col-leagues in the executive branch.71 For example, Surgeon General Steinfeld refused to endorse the commission recommendations, and Dr. Jerome Jaffe, director of the White House Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention (SAODAP), refused to say any-thing at all. Yet both men privately agreed with the commission approach.

The commission's disenchantment with the possession penalty rested on both philosophical and practical arguments. First, the report took cognizance of "the nation's philosophical preference for individual privacy" and the "high place traditionally occupied by the value of privacy in our constitutional scheme," and noted that possession penalties in the "narcotics" area represented a departure from tradition. "Accordingly," the commission con-tended,

[w] e believe that government must show a compelling reason to justify invasion of the home in order to prevent personal use of marihuana. We find little in marihuana's effects or in its social impact to support such a determination. Legislators enacting Prohibition did not find such a compelling reason 40 years ago; an,d we do not find the situation any more compelling for marihuana today. 72

Then the commission recited the practical costs and functional disutilities associated with prohibition of possession. Selective enforcement, selective prosecution, frustration of other social con-trol ins'titutions, misallocation of resources, collision with constitu-tional limitations, and disrespect for law among the young, overwhelmingly outweighed the minimal "deterrent" and symbolic values of the possession laws. In essence, law enforcement authori-ties had already adopted a passive containment policy aimed only at indiscretion; in the commission's view, such a result could be achieved more honestly, artfully, and fairly without the possession penalty.

The commission approach had its own symbols, of course. The commission labeled its scheme "partial prohibition" in an attempt to avoid the implication that it was urging the "legalization" of marihuana use. More important, under the commission's proposed scheme, criminal liability would still attach to public activities, such as use, possession of more than one ounce, and distribution of any amount. Finally, any amount of marihuana possessed in public would be contraband—this was the most concrete symbol of the discouragement policy. All in all, these recommendations were clearly designed to ameliorate only the worst excesses of a pro-hibitory scheme while retaining the trappings of illegality.

The game of symbol selection was played out in a footnote, where five commissioners qualified their assent to the decriminaliza-tion scheme." Three members of the commission (Congressmen Rogers and Carter and Attorney Mitchell Ware) thought "contra-band" was not a potent enough symbol; they would have levied a civil fine on anyone possessing any amount of marihuana in public, even if for their own use. Senators Hughes and Javits, on the other hand, would have removed a larger sphere of consump-tion-related conduct from the criminal law:

The contraband device, the not-for-profit sale, and public pos-session of some reasonable amount which should be presumed to be necessarily incident to private use should all be removed from the ambit of legal sanction. To do so would be to strike down "symbols" of a public policy which has never been ade-quately justified in the first instance. Such steps would in no way jeopardize the firm determination of the Commission that the use of marihuana ought to be discouraged.

Politics was not an irrelevant consideration in this game ot symbols. Four of the footnote dissenters were federal legislators and the fifth was also a political figure. For the benefit of their respective constituencies, the two liberal senators staked out a position slightly to the left of the commission, while the two Southern congressmen insisted on being slightly to the right.

It is also interesting to note that the commission unanimously rejected the regulatory alternative (legalization). Numerous critics of the Marihuana Commission Report have detected in this fact a compromise to secure unanimity on a decriminalization recom-mendation or to escape the shackles of the president's May Day statement.74‘ Others have seen it instead as a reflection of the basically conservative composition of the panel. In any case, the commission's rationale is classically conservative—solicitous of the prevailing order and wary of disruption of the social fabric. The rejection of legalization was premised entirely on preventive considerations: avoidance of cultural dislocation and social conflict and prevention of a public health problem. The commission did not rule out a regulatory approach at some later time. Instead, in an aside well hidden in the report, the commission noted:

Our doubts about the efficacy of existing regulatory schemes, together with an uncertainty about the permanence of social interest in marihuana and the approval inevitably implied by adoption of such a scheme, all impel us to reject the regulatory approach as an appropriate implementation of a discouragement policy at the present time.

Future policy planners might well come to a different conclu-sion if further study of existing schemes suggests a feasible model; if responsible use of the drug does indeed take root in our society; if continuing scientific and medical research un-covers no long-term ill effects; if potency control appears feasi-ble; and if the passage of time and the adoption of a rational social policy sufficiently desymbolize marihuana so that avail-ability is not equated in the public mind with approval:75

Politics and Symbolism

Among national politicians the Marihuana Commission Report provoked predictable reactions. Two days after the report was issued, President Nixon expressed his continuing preference for the status-quo: "I oppose the legalization of marihuana and that in-cludes sale, possession and use. I do not believe you can have effective criminal justice based on a philosophy that something is half-legal and half-illegal."76 Both the commission and NIMH had expressed the hope that the factual issues would be neutralized in the continuing public debate about marihuana policy. The presi-dent complied with this request by confining his objection only to the commission's policy recommendations. He noted that this was the "one aspect" of the report with which he disagreed, adding that "it is a report which deserves consideration and it will receive it." President Nixon did not indicate explicitly whether this meant he now had rejected the stepping-stone hypothesis which he had publicly embraced the year before.

The commission, in response to the president's statement, pointed out that there was ample precedent in American law for a partial prohibition scheme, and that this was actually the tradi-tional way of dealing with sumptuary behaviors: the criminal sanction extends to the gambling entrepreneur, not the gambler; to the distributor of pornographic material, not the private consumer; to the person who sells alcohol and tobacco to underage consumers, not the youths themselves. And the commission also recalled that during alcohol prohibition, it was the bootlegger, not the individual consumer, who was the criminal. 77

Other administration officials were more vociferous in their opposition to the commission's recommendations. BNDD's Director Ingersoll noted that removal of the criminal sanction from mari-huana and other drugs would mean the fight against drug abuse had been "lost altogether." He added, somewhat obliquely: "It is our duty not only to protect the public in the streets from vicious criminals but to protect the public from harmful ideas."78 Vice-President Agnew thought it was "wrong of us to in any way en-courage the use of marihuana." The commission's recommendations "frightened" him, he said, "because no nation in world history has ever legitimated the use of marihuana." Use of the drug in Eastern countries, he noted further, "has really debilitated those societies.'"

Throughout the country law enforcement officials condemned the report, either ridiculing what they perceived to be a logical inconsistency or lambasting the commission and its findings. For example, Mayor Frank Rizzo of Philadelphia, former police com-missioner of the nation's fourth largest city, stated that "somewhere, sometime, we're going to have to clear the cobwebs from the minds of do-gooders who write reports like this." He was "absolutely opposed to sanctioning the private smoking of marihuana," he said, because in his "experience, marihuana has been only a vehicle to the use of harder drugs."a°

Mayor Rizzo was of the same mind as Harry Anslinger, who branded the commission's recommendations "terrifying," predict-ing that their adoption would have "very serious national reper-cussions." If society were to allow "smoking in secret without any penalty," he explained, "then I think in a couple of years well have about a million lunatics filling up the mental hospitals and a couple of hundred thousand more deaths on the highways—just plain slaughter on the highways." 81

On the other side of the political spectrum, liberal public officials from both parties welcomed the Marihuana Commission Report. Senator Percy of Illinois, a Republican, agreed that "substantial public use of marihuana, coupled with the fact that research to date has uncovered relatively few harmful effects to the individual or society" justified removal of criminal penalties. He hoped that this society would now deal "honestly" with the marihuana issue on the basis of the "evidence and sound conclu-sions of the Commission."82 Senator Muskie, Democrat from Maine, said he supported the commission's "progressive approach."R8

The "acceptable middle ground" embodied in the commission's recommendations appealed to Senators Percy and Muskie. But the "middle ground" of "decriminalization" was not yet perceived by all politicians to be "acceptable," a realization which had some effect on the presidential campaign of South Dakota Senator George McGovern. All of the Democratic and Republican candidates had been polled on the marihuana issue by the National Organization for Reform of the Marijuana Laws (NORML), a Washington-based lobby funded primarily by the Playboy Foundation. Together with Senators Humphrey, Muskie, and Hartke, New York City Mayor Lindsay, former Senator McCarthy, Congressman McCloskey (Calif-ornia), and Congresswoman Chisholm (New York), Senator Mc Govern expressed support for decriminalization. With regard to legalization, all but McCarthy, Chisholm, and McGovern backed off." The South Dakota senator had also publicly expressed his inclin-ations toward legalization. 85

When the Democratic nomination fight heated up in the late spring, McGovern's candor on the marihuana issue, as well as on other civil libertarian matters such as amnesty for draft resisters and legalized abortion, came back to haunt him. First, Senator Jackson and later Senator Humphrey labeled their rival as "the Triple A candidate,'' a proponent of "acid, amnesty and abortion." "Acid" of course referred to nothing more than the senator's stand on marihuana, and reflected the persistent attempt to associate marihuana law reform with approval of all drug use. Pretty soon, en route to his party's nomination, the candidate retreated and began urging only a "reduction of harsh penalties" for marihuana use.

Well before the McGovern episode, Republican Senator Dominick of Colorado had exclaimed: "Coming out for legalized pot is like putting your head right on the chopping block. .. . I think this (Commission) Report is two years ahead of itself. What is needed is a massive selling job across the country because anybody who proposes something like this is really headed for trouble right now."' 86 The marihuana issue dropped out of the presidential campaign.

There were those, of course, who did not want the issue to recede. The advocates of legalization had mixed reactions to the Marihuana Commission Report. John Kaplan, law professor and author of Marijuana: The New Prohibition, hailed the decriminali-zation proposal as a "step in the right direction" although an insufficient one. He added: "I think Nixon did his best to appoint a Commission which was biased toward his views against the legalization of marihuana, but I am overjoyed to see they gave him an honest Report."87 Lester Grinspoon, Kaplan's alter ego from the medical profession and author of Marijuana Reconsidered, was not so kind. He lambasted the commission for its writing style, "sermon-like tone," inconsistencies, and "wishful thinking." Ac-knowledging that the commission deserved "credit" for moving the marihuana issue "in the right direction," Grinspoon nevertheless thought it had "produced only, at most, a half a loaf," and he thought he knew why: -

After my testimony before the Commission last May (1971) .. . I got the impression that [one of the commissioners] saw as an important aspect of the Commission's task that of finding a policy which offended the fewest people. Indeed, the Commis-sion in its surveys did much to learn how people thought and felt about marihuana. The only way I can reconcile some of the inconsistencies in its report is to believe that its policy recom-mendations derive not solely from medical, psychological, and social considerations, but as well from the political reality.88

Some advocates were not so disrespectful of the "political reality." The two major lobbying organizations both praised the commission. AMORPHIA, based in California, had been formed in 1969 by Michael Aldrich, one of the original proponents of legal marihuana. Upon release of the Marihuana Commission Report, Amorphia applauded "the greatest single step in alleviating a 40 year accumulation of official myths and falsehoods in this area." As to politics, the group noted that decriminalization is a "politically inescapable step in reeducating the public," although "completely untenable as a long-term policy." 89

Similarly, NORML, which had been bankrolled by the Playboy Foundation in January 1971, praised the commission for "taking a courageous step in light of the prevalence of misinformation and fear" and promised to lobby for the decriminalization scheme, "in every way possible." " NORML had not always been so apprecia-tive of the commission. In the early days when marihuana advocates were sniping at the commission's credibility, NORML was a fledg-ling group attempting to establish some clout of its own. Its executive director, Keith Stroup, requested an opportunity to testify before the commission at its initial hearings in Washington. He was told by Michael Sonnenreich, the commission's staff director, that the commission was carefully selecting a group of experts in the area to present all viewpoints. Since the commission could make available only a limited number of slots, he did not think NORML would be an appropriate choice. When Stroup countered with the possibility that former Attorney General Ramsey Clark might be willing to represent the group, Sonnenreich viewed this as publicity-hunting, noting that the reform viewpoint would be adequately represented without the former attorney general.

Stroup reported these events to muckraking journalist Jack Anderson, who called Sonnenreich and then printed the story.94 Ultimately, the commission did call Clark, who claimed that he had rio intention of representing NORML and did not desire to testify. For the remainder of the commission's first year, Stroup—who did testify at a later public hearing—carefully scrutinized commission activities, freely predicting that the commission would recommend nothing more substantial than a further reduction in penalties.

By March 1972 when the Marihuana Commission Report was issued, NORMI, had gotten its feet on the ground and realized the political importance of the panel's recommendations. Naturally, the group did wish the commission had gone further:

The Commission did balk at setting up a regulatory scheme. They reasoned that to do so would serve to institutionalize mari-juana use at a time when they were still hoping marijuana would prove a mere fad and disappear. It is on this point we most strenuously disagree. There is absolutely no evidence that mari-juana use will disappear. In fact, it has been around for centuries, and its popularity continues to grow at a great rate in this country. It appears likely that marijuana use will be as much a part of our future culture as will the use of cigarettes and even the Commission recognizes that if this is the case, then a regulatory scheme, with controls over the drug and who gets it, would be preferable. This is why NORML favors legalization. We believe the Commission is aware of this inherent weakness in their report, but chose to avoid the possible political reper-cussions of such far reaching recommendations. We regret this failure.92

The Politics of Repeal

Legislators everywhere had held the marihuana issue at arms' length pending a definitive scientific determination of marihuana's harm-fulness. Publication of the Marihuana Commission Report in the spring naturally loosed an army of marihuana reformers on the state houses. Despite the addition to their ranks of the former deputy director of BNDD, John Finlator,93 the going was rough. This was, after all, a political year, and the summer adjournments came without any reform.

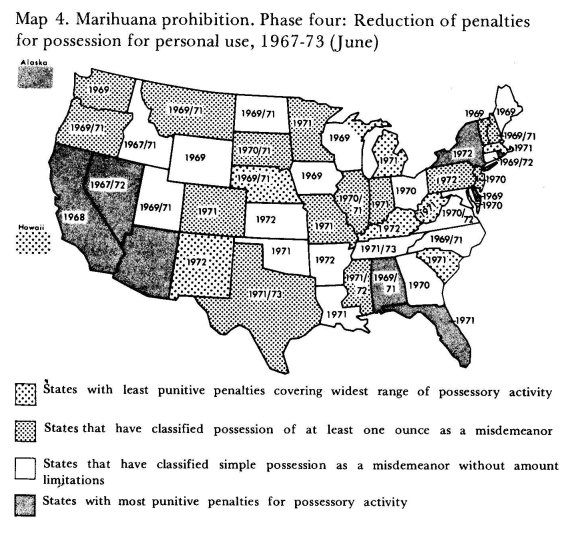

The penalty reduction phase of marihuana prohibition had been all but completed in 1971. In that year sanctions were ameliorated by fifteen states that had not already done so in the three previous years and were reduced even more by fourteen other states. By the end of 1971 only three states (Texas, Pennsylvania, and Rhcade Island) maintained mandatory felony penalties for possession, al-though four other states (California, Arizona, Mississippi, and Nevada) allowed prosecution as a misdemeanor or a felony in the discretion of the prosecutor.94

Meanwhile, bills that would have reduced possession penalties were actually defeated in New York and California:95 The New York measure was defeated in face of endorsement by the governor, the state District Attorney's Association, and a state Advisory Commission on Drugs. In California, the proposed reduction of possession to a nondiscretionary misdemeanor passed the general assembly before it was defeated in the senate.

Despite the Marihuana Commission Report, the political obstacle to substantial legislative change of the marihuana laws was still a formidable one. Senators Hughes and Javits and Congressman Koch introduced identical decriminalization measures in both houses of Congress. No action was anticipated and none was taken. An attempt by a Special State Committee in Texas to force reconsideration of the marihuana issue aborted when the governor would not open the call of a special legislative session beyond budgetary issues.

The only exception to the political stalemate in 1972 was not too surprising: on 16 May the city council of Ann Arbor, Michigan, a city of 110,000 and home of the sprawling 34,000-student University of Michigan, enacted an ordinance setting a $5 fine for use, possession, or sale of marihuana. 96 Under a ruling by the Michigan attorney general localities are permitted to deviate from the state penalty structure upon a demonstration of "special circumstances." That Ann Arbor is a special location is clearly established by the fact that the ordinance was passed by a six-to-five majority coalition composed of four Democrats and two mem-bers of the Human Rights Party (aged twenty-two and twenty-six).97

Outside Ann Arbor, however, a legislative consideration of the merits—rather than the politics—of decriminalization was impossi-ble until 1973. In response, reformers sought to bypass the legisla-tive process altogether—through the judiciary, through administrative action, and by appealing directly to the people.

We noted earlier that appellate courts had become restless about the marihuana laws during the retrenchment and penalty-reduction phases, but had refused to invalidate them on constitutional grounds. In 1971, however, two state courts and a federal court held that it was unconstitutional to classify marihuana as a narcotic, and several judges in Illinois, Michigan, and Hawaii concluded that the marihuana possession penalty was itself unconstitutional."

The vehicle for such a declaration is the right of privacy on which the Supreme Court based its 1965 decision invalidating Connecticut's prohibition of the use of birth control devices, its 1969 decision overturning prohibitions of the private possessiron of obscene literature, and its 1973 decision severely limiting the function of antiabortion statutes.99 If the right of privacy is thought to be involved, the burden of proof is shifted to the government to demonstrate a compelling state interest in intruding into the private lives of marihuana smokers. Whatever the merits of such an ar'gu-ment from the standpoint of constitutional jurisprudence, it is appealing to those courts who are otherwise inclined to overturn the marihuana laws. 'The reformers have correctly surmised that the judiciary is unlikely to remain oblivious to perceived injustices under the marihuana laws, especially if the political process does not respond. Such a judicial perspective motivated the American Civil Liberties Union to launch a full-scale attack on the marihuana laws in early 1972.

At the administrative level, NORML, together with the American Public Health Association and the Institute for the Study of Health and Society, petitioned BNDD to remove marihuana from the list of controlled substances under the CSA, thereby legalizing it under federal law. There was, of course, no possibility that BNDD would do so. As an alternative, the petitioners asked that marihuana be removed from Schedule I (with heroin and LSD) and placed in Schedule V together with over-the-counter preparations such as codeine cough syrups. In that event, all nonmedical marihuana distribution and use would be a misdemeanor. BNDD refused even to accept the petition for filing on the ground that the CSA rescheduling procedures do not apply when control of a substance is required by United States obligations under international law in effect at the time the CSA was passed."° Since the United States was obligated to control marihuana by the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, administrative action was, under the bureau's reasoning, impossible. NORML's appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals was pending when this book went to press:1°1

The challengers also went to the people. In a move initiated as an "educational tool" in the summer of 1971, the leaders of the California Marihuana Initiative collected 382,095 signatures on an initiative petition placing the following proposition on the ballot in November 1972:

No person in the State of California 18 years of age or older shall be punished criminally, or be denied any right or privilege, by reason of such person's planting, cultivating, harvesting, drying, processing, otherwise preparing, transporting, or posses-sing marijuana for personal use, or by reason of that use.

This provision shall in no way be construed to repeal existing legislation, or limit the enactment of future legislation, prohibit-ing persons under the influence of marijuana from engaging in conduct that endangers others.

Support by Amorphia and NORML, together with the Commis-sion's endorsement of a similar decriminalization scheme, raised the hopes of the CMI organizers. Their effort had gained political respectability over the course of a year and "Proposition 19" was endorsed by the Los Angeles Democratic Central Committee, the California Bar Association, the San Francisco Bar Association, and the Los Angeles County Grand Jury. CMI leaders felt that decrimi-nalization was inevitable: "If we lose this time, we will keep trying until we get it passed."1°2 CMI did lose—by a 2 to 1 margin—al-though it actually passed in San Francisco County and got 49 percent ot the vote in Marin County and 38 percent in Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties.`103

Similar initiative campaigns in Arizona, Florida, Oregon, Wash-ington, and Michigan were aborted for lack of signatures. In Arizona, where 23,000 of the required 40,000 signatures were obtained, Senator Barry Goldwater noted that the decriminaliza-tion proposal would not have had a chance on his state's ballot anyway: "Pot is like gambling. People in my state have voted down legalized gambling at least six times, even though most people like to gamble. I think the only chance for new marihuana laws is through the legislatures."104

Senator Goldwater's remark and the CMI defeat highlight an important point. Repeal of a criminal law by political action is a rare occurrence. Disapproval by one generation of a particular behavior, once embodied in a criminal prohibition, fixes a deep imprint on the attitude of those that follow. As long as the domi-nant social group continues to disapprove the behavior, however mildly, removal of a criminal proscription is unlikely; for it is perceived that removal of the symbol of disapprobation will symbolize an approval of the behavior itself. And this will be true regardless of the social costs of the criminal law or whether the law is enforced at all. Perpetuation of unenforced criminal sanciions against fornication, adultery, homosexuality, and gambling are illustrative of the potency of symbols.

Criminal prohibitions have been successfully repealed by politi-cal action only when the dominant group no longer disapproves. of the behavior (gambling); when the behavior is so widespread and visible that enforcement becomes intolerable, and must be replaced by some overt regulation (alcohol prohibition); when the moral premise underlying societal disapproval can be neutralized by counteracting social benefits (abortion, gambling); or when the law may be changed without attracting public attention(homosexuality).

On the marihuana issue, as Senator Goldwater implied, the dominant social group simply could not bring itself to remove the symbol of disapproval. Through formal reduction of penalties and emergence of enforcement desuetude, the most excessive social costs of prohibition were slowly being minimized. Yet, since 200,000 persons a year were still being arrested for possession of mari-huana, these costs had not been eliminated. Pointing in the long run for some formal regulation of distributional activity, the re-formers aimed in 1972 to generate the necessary changes in public opinion to support a new consensus. They viewed decriminalization as a major step in this regard because a willingness to remove the symbolic possession offenses would itself reflect a weakening of social antipathy toward use of the drug. If this were true, the final step in the reform program, adoption of a regulatory model, would be easy.

Public opinion does not change overnight, however, as the CMI illustrated. Many opinion makers and professional groups such as the National Council of Churches, the National Education Associa-tion, the American Public Health Association, and the New York State Bar Association endorsed decriminalization. When the National Coordinating Council on Drug Information polled its membership, which includes groups like the American Legion and the Boy Scouts, it found that substantially more than half its 133- member organizations officially favored either decriminalization or legalization.1135 The Consumers Union sponsored and published a study by Brecher that recommended a regulatory approach.106

Among editorial writers and columnists, a healthy proportion endorsed the commission proposals, induding the New York Times, Newsday (Long Island, New York), the San FranciscoExaminer and the San Francisco Chronicle, the Miami News, the Louisville Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Knoxville News-Sentinel, the Chicago. News, the Minneapolis Star, the Portland Oregonian, the Birmingham Post-Herald, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Washington Evening Star, and the Cincinnati Enquirer.1°7 Others, including the Charlotte (N.C.) Observer and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch , prefen-ed a regulatory model and accused the commission of compromise.'" Of particular interest in this regard was the strong endorsement of William F. Buckley, Jr., and several other com-mentators from the National Review, who urged "American Conservatives [to] revise their position on Marijuana." 109

Despite the breadth of reform sentiment in the press, the possession penalty was too firmly entrenched to be uprooted so suddenly. A small percentage of editorial opinion, particularly in the South, branded the Marihuana Commission Report and its decriminalization proposal "worthless" and "permissive," alleging, for example, that it was "tantamount to encouraging and sanction-ing use" of the drug.tio A more common thrust of editorial opinion opposing the proposed policy was to question its logic and plead instead for further reduction in penalties.n4 Of this group, only the Los Angeles Times faced the symbolism issue head on, ac-knowledging that the symbol carried its costs and proposing desuetude instead:

Should legal restrictions on private use of the drug ... be eliminated entirely? We think not, first because scientific evi-dence about marijuana's dangers remains inconclusive, second because such a move might well encourage a spread in use. The real legal issue, it seems to us, is how vigorously should existing prohibitions be enforced.