|

THE TREASURY DEPARTMENT went to Capitol Hill to secure passage of the Marihuana Tax Act with an open-and-shut case. Anslinger and his colleagues stressed four points in their testimony before the House Ways and Means Committee and a subcommittee of the Senate Finance Committee: marihuana was a disastrous drug; its use was increasing alarmingly and had generated public hysteria; state legislation had proved incapable of meeting the threat posed by the weed, and federal action was therefore required; and, the government might best act through separate legislation rather than through an amendment to the Harrison Act.

For five mornings in the House and one morning in the Senate, the legislators and bureaucrats convinced one another of the need for this legislation. The selection and questioning of witnesses reflect clearly the consensus among the participants regarding the relative importance of the matters upon which the legislation was predicated. Of primary interest was the question of federal resRon-sibility. The New Deal Congress had been flexing its muscles for four years and resented any suggestion that any "national" problem was beyond its competence. If the Treasury "experts" contended that marihuana was a national menace, then the United States Congress was committed in principle to federal action. The threat of invalidation by the Supreme Court posed the only restraint, and even that issue was rapidly becoming one only of form.

What's Wrong with Marihuana?

The narcotics bureaucracy had no definitive scientific study of the effects of marihuana to present to the Congress. Even so, one might have thought the Treasury Department would have submitted a synthesis of available scientific information, or perhaps would have summoned a number of private investigators or the government's own public health experts to testify about the drug's effects. None of these things were done. No statement was submitted by the Public Health Service. Neither of the government's own public health experts, Drs. Treadway and Kolb, testified, nor did Drs. Bromberg and Siler who had recently published scientific articles on the effects of cannabis in humans.

Instead, the scientific aspects were summarized briefly by the FBN, a law enforcement agency. The bureau submitted a written statement which acknowledged some uncertainty within the scien-tific community. Then they dismissed it:

Despite the fact that medical men and scientists have disagreed iTon the properties of marihuana, and some are inclined to minimize the harmfulness of this drug, the records offer ample evidence that it has a disastrous effect upon many of its users. Recently we have received many reports showing crimes of violence committed by persons while under the influence of marihuana. . . .

The deleterious, even vicious, qualities of the drug render it highly dangerous to the mind and body upon which it operates to destroy the will, cause one to lose the power of connected thought, producing imaginary delectable situations and gradually weakening the physical powers. Its use frequently leads to insanity.

I have a statement here, giving an outline of cases reported to the Bureau or in the press, wherein the use of marihuana is connected with revolting crimes.1

Only the Gomila and Stanley articles were presented to support this statement.2 Stanley's article cited the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission report, and Gomila cited Bromberg's study, but neither of these reports were themselves presented, nor were the Canal Zone studies. The few hints of uncertainty in the bureau's written statement disappeared in Anslinger's oral testimony.

Mr. ANSLINGER. I have another letter from the prosecutor at a place in New Jersey.

It is as follows:

THE INTERSTATE COMMISSION ON CRIME,

March 18, 1937

CHARLES SCHWARZ,

Washington, D.C.

MY DEAR MR. SCHWARZ: That I fully appreciate the need for action, you may judge from the fact that last January I tried a murder case for several days, of a particularly brutal character in which one colored young man killed another, literally smash-ing his face and head to a pulp, as the enclosed photograph demonstrates. One of the defenses was that the defendant's intellect was so prostrated from his smoking marihuana cigarettes that he did not know what he was doing. The defendant was found guilty and sentenced to a long term of years. I am con-vinced that marihuana had been indulged in, that the smoking had occurred, and the brutality of the murder was accounted for by the narcotic, though the defendant's intellect had not been totally prostrate, so the verdict was legally correct. It seems to me that this instance might be of value to you in your campaign.

Sincerely yours,

RICHARD HARTSHORNE.

Mr. Hartshorne is a member of the Interstate Commission on Crime.

We have many cases of this kind.

Senator BROWN. It affects them that way?

Mr. ANSLINGER. Yes.

Senator DAVIS (viewing a photograph presented by Mr. Ans-linger). Was there in this case a blood or skin disease caused by marihuana?

Mr. ANSLINGER. No. this is a photograph of the murdered man, Senator. It shows the fury of the murderer.

Senator BROWN. That is terrible.

Mr. ANSLINGER.That is one of the worst cases that has come to my attention, and it is to show you its relation to crime that I am putting those two letters in the record. . . .

I have a few cases here that I would just like to tell the com-mittee about. In Alamoosa, Colorado, they seem to be having a lot of difficulty. The citizens petitioned Congress for help, in addition to the help that is given them under the State law. In Kansas and New Mexico also we have had a great deal of trouble.

Here is a typical illustration: A 15-year-old boy, found mentally deranged from smoking marihuana cigarettes, furnished enough information to the police officers to lead to the seizure of 15 pounds of marihuana. That was seized in a garage in an Ohio town. These boys had been getting marihuana at a play-ground, and the supervisors there had been peddling it to children, but they got rather alarmed when they saw these boys developing the habit, and particularly when this boy began to go insane.

In Florida some years ago we had the case of a 20-year-old boy who killed his brothers, a sister, and his parents while under the influence of marihuana.

Recently, in Ohio, there was a gang of very young men, all under 20 years of age; every one of whom confessed that they had committed some 38 holdups while under the influence of the drug.

In another place in Ohio a young man shot the hotel clerk while trying to hold him up. His defense was that he was under the influence of marihuana. .. .

Senator BROWN. There is the impression that it is stimulating to a certain extent? It is used by criminals when they want to go out and perform some deed that they would not commit in their ordinary frame of mind?

Mr. ANSLINGER. That was demonstrated by these seven boys, who said they did not know what they were doing after they smoked marihuana. They conceived the series of crimes while in a state of marihuana intoxication.

Senator DAVIS. How many cigarettes would you have to smoke bef6re you got this vicious mental attitude toward your neighbor? Mr. ANSLINGER. I believe in some cases one cigarette might develop a homicidal mania, probably to kill his brother. It de-pends on the physical characteristics of the individual. Every indi.vidual reacts differently to the drug. It stimulates some and others it depresses. It is impossible to say just what the action of the drug will be on a given individual, or the amount. Probably some people could smoke five before it would take effect, but all the experts agree that the continued use leads to insanity. There are many cases of insanity.3

Anslinger's testimony was the only information on effects which was presented to the Senate subcommittee.

In the House, Anslinger brought along a representative from the scientific community. Instead of presenting one of the few re-searchers who had done any significant research into the effects of cannabis on humans, however, the bureau chose a Temple Univer-sity pharmacologist, Dr. James Munch, whose experience was confined to limited experimentation of the effects of cannabis on dogs. One participating committeeman, Congressman McCormack (later the Speaker), soon realized how little Dr. Munch could contribute, and with his questions began to assume the role of the expert witness on the effects of cannabis in man:

Dr. MUNCH. In connection with my studies of Cannabis, or marihuana, I have followed its effects on animals and also, so far as possible, its effect upon humans.

Continuous use will tend to cause the degeneration of one part of the brain, that part that is useful for higher or physic reasoning, or the memory. Functions of that type are localized in the cerebral cortex of the brain. Those are the disturbing and harmful effects that follow continued exposure to marihuana....

I have found in studying the action on dogs that only about 1 dog in 300 is very sensitive to the test. The effects on dogs are extremely variable, although they vary little in their suscepti-.bility. The same thing is true for other animals and for humans.

Animals which show a particular susceptibility, that is, which show a response to a given dose, when they begin to show it will acquire a tolerance. We have to give larger doses as the animals are used over a period of 6 months or a year. This means that the animal is becoming habituated, and finally the animal must be discarded because it is no longer serviceable.

Mr. McCORMACK. We are more concerned with human beings than with animals. Of course, I realize that those experiments are necessary and valuable, because so far as the effect is concerned, they have a significance also. But we would like to have whatever evidence you have as to the conditions existing in the courttry, as to what the effect is upon human beings. Not that we are not concerned about the animals, but the important matter before us concerns the use of this drug by human beings.

Mr. McCORMACK. I take it that the effect is different upon different persons.

Dr. MUNCH. Yes, sir.

Mr. McCORMACK. There is no question but what this is a drug, is there?

Dr. MUNCH. None at all.

Mr. McCORMACK. There is no dispute about that?

Dr. MUNCH. No.

Mr. McCORMACK. Is it a harmful drug?

Dr. MUNCH. Any drug that produces the degeneration of the brain is harmful. Yes; it is.

Mr. McCORMACK. I agree with you on that, but I want to ask you some questions and have your answers for the record, because they will assist us in passing upon this legislation. Dr. MUNCH. I have said it is a harmful drug.

Mr. McCORMACK. In some cases does it not bring about ex-treme amnesia?

Dr. MUNCH. Yes; it does.

Mr. McCORMACK. And in other cases it causes violent irrita-bility?

Dr. MUNCH. Yes, sir.

Mr. McCORMACK. And those results lead to a disintegration of personality, do they not?

Dr. MUNCH. Yes, sir.

Mr, McCORMACK. That is really the net result of the use of that drug, no matter what other effects there may be; its continued use means the disintegration of the personality of the person who uses it?

Dr. MUNCH. Yes; that is true.

Mr. McCORMACK. Can you give us any idea as to the period of continued use that occurs before this disintegration takes place ? Dr. MUNCH. I can only speak from my knowledge of animals. In some animals we see the effect after about 3 months, while in others it requies more than a year, when they are given the same dose.

Mr. McCORMACK. Are there not some animals on which it reacted, as I understand it, in a manner similar to its reaction on human beings? Is that right?

Dr. MUNCH. Yes, sir.

Mr. McCORMACK. Have you experimented upon any animals whose reaction to this drug would be similar to that of human beings?

Dr. MUNCH. The reason we use dogs is because the reaction of dogs to this drug closely resembles the reaction of human beings. Mr. McCORMACK. And the continued use of it, as you have observed the reaction on dogs, has resulted in the disintegration of personality?

Dr. MUNCH. Yes. So far as I can tell, not being a dog psychologist, the effects will develop in from 3 months to a year. Mr. McCORMACK. The recognition of the effects of the use of this drug is only of comparatively recent origin, is it not?

Dr. MUNCH. Yes; comparatively recent.

Mr. McCORMACK. I suppose one reason was that it was not used very much.

Dr. MUNCH. That is right.

Mr. McCORMACK. I understand this drug came in from, or was originally grown in, Mexico and Latin American countries.

Dr. MUNCH. "Marihuana" is the name for Cannabis in the Mexican Pharmacopoeia. It was originally grown in Asia.

Mr. McCORMACK. That was way back in the oriental days. The word "assassin" is derived from an oriental word or name by which the drug was called; is not that true?

Dr. MUNCH. Yes, sir.

Mr. McCORMACK. So it goes way back to those years when hashish was just a species of the same class which is identified by the English translation of an okiental word; that is, the word "assassin"; is that right?

Dr. MUNCH. That is my understanding... .

Mr. McCORMACK. Can you give us any information about the growth in recent years of the use of it as a drug, in connection with the purposes that this bill was introduced to meet?

Dr. MUNCH. You mean the illicit use rather than the medicinal use?

Mr. McCORMACK. Exactly.

Dr. MUNCH. The knowledge I have in that connection is based on contacts with police officers as they collected material, even in Philadelphia. They tell me that until 10 years ago they had no knowledge of it, but now it is growing wild in a number of different places.

I was in Colorado about 3 years ago, going there as a witness in a prosecution brought under the Colorado act in connection with the use of marihuana. The police officers there told me its use developed there only within the last 3 or 4 years, starting about 1932 or 1933.

Mr. McCORMACK. Has there been a rapid increase in the use of marihuana for illicit purposes—and I use the word "illicit" to describe the situation we have in mind?

Dr. MUNCH. It is my understanding that there has been. Mr. McCORMACK. There is no question about that, is there? Dr. MUNCH. No, sir; there is not.

Mr. CULLEN. We thank you for the statement you have given to the committee.4

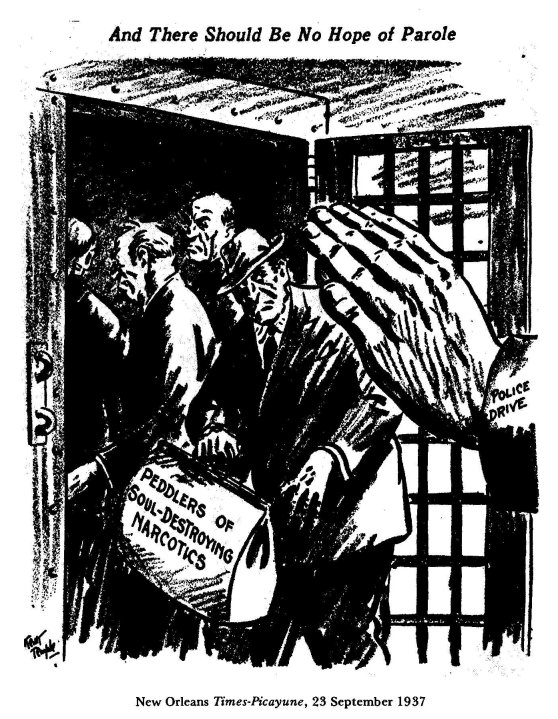

The Birth of a Menace

The second component of the bureau's case was the contention that marihuana use had spread alarmingly in recent years, provok-ing a public outcry. To demonstrate this, the bureau submitted only the 1936 letter from the city editor of the Alamoosa Daily Courier and the Gomila article, hardly firm evidence of any such alarming increase.5 The Congress, however, was neither in the mood nor in a position to question Anslinger's contentions. What did interest legislators, however, was why use suddenly increased in 1935. In both houses Anslinger dismissed the suggestion that drug users turn to marihuana when other drugs are not available:

Senator BROWN. Do you think that the recent great increase in the use of it that has taken place in the United States is probably due to the heavy hand of the law, in its effect upon the use of other drugs, and that persons who desire a stimulant are turning to this because of enforcement of the Harrison Narcotics Act and the State laws?

Mr. ANSLINGER. We do not know of any cases where the opium user has transferred to marihuana. There is an entirely new class of people using marihuana. The opium user is around 35 to 50 years old. These users are 20 years old, and know noihing of heroin or morphine.

Senator BROWN. What has caused the new dissemination of it? We did not hear anything of it until the last year or so. Mr. ANSLINGER. I do not think that the war against opium has very much bearing upon the situation. That same question has ,been discussed in other countries; in Egypt particularly, where a great deal of hasheesh is used, they tried to show that the marihuana user went to heroin, and when heroin got short he jumped back to hasheesh, but that is not true. This is an entirely different class. I do not know just why the abuse ot marihuana has spread like wildfire in the last 4 or 5 years.6

When asked to estimate the number of users, Anslinger reported that the states had made about 800 marihuana arrests, 400 in California alone, the previous year. He suggested that the California authorities had cracked down and that if the other states were more efficient, there would have been more arrests, although he admitted that use probably was not as prevalent anywhere else as in California?

Arrest figures are singularly unhelpful in ascertaining incidence of use, being a function more of enforcement policy, investigative activity, and statistical reporting than of the size of the using population. But even if a significant leap in arrest figures could be taken to indicate increased incidence of use, Anslinger's figures were meaningless. There was no systematic reporting of state arrests, so Anslinger could not possibly have compiled a reliable figure. Even so, he did not present figures for prior years for comparative purposes, and 800 arrests in a year could not have been much of an increase. Some perspective is provided by the fact that in 1970, when statistical reporting was still primitive, there were an estimated 200,000 marihuana arrests and perhaps 60,000 were in California.

All in all, Anslinger's bold assertion that marihuana use had markedly increased was entirely unsupported. But that, of course, did not make any difference. Anslinger used the newspaper cam-paigns of 1935 to paint a credible picture of public hysteria. Just as such propaganda generated interest in the Uniform Act among state legislatures, it created a "felt need" for federal legislation in the Congress, despite the fact that there is no evidence this public hysteria about marihuana really existed on any signficant scale.8

The Need for National Legislation

The third component of the bureau's case was that even though every state now had marihuana legislation, local authorities could not cope with the marihuana menace. To support this proposition the bureau offered editorial pleas from the Washington newspapers and Anslinger's testimony that officials of several states had re-quested federal help. The FBN offered no information on why the states needed help. Was there a major interstate trafficking network which could not be broken by local authorities?

Senator Brown realized the importance of this question and asked Anslinger to "make clear the need for federal legislation. You say the states have asked you to do that. I presume it is because of the freedom of interstate traffic that the States require the legislation." Anslinger agreed: "We have had requests from the States to step in because they claimed it was not growing in that State, but that it was coming in from another state."9 He presented nothing to support this statement, no letters from local authorities and no investigative reports by FBN agents describing the trafficking apparatus. Although absence of recorded evidentiary support is not necessarily conclusive on this matter, nothing remains today in the FBN's files which would have supported the contention.

The bureau's implicit attitude was that most of the states were not trying very hard to enforce their marihuana legislation, due to either inadequate resources or simple lack of interest. The need for federal legislation did not arise from the limitations imposed by state boundaries but from the inefficiency of state authorities within their own jurisdictions, as perceived by the bureau. If the bureau was given statutory responsibility through a federal law on marihuana, Anslinger hoped to spark state and local enforcement in those jurisdictions which had not yet taken the problem seriously. In the states which had already begun to suppress marihuana—New York, Louisiana, Colorado, and California—the bureau would assist by supplying additional manpower and money.")

The congressmen and senators participating in the hearings accepted the bureau's argument. In fact, Senator Brown, chairman of the subcommittee which considered the legislation in the Senate, and Chairman Doughton of the Ways and Means Committee had been thoroughly briefed by the bureau in advance of the hearings. Again and again, Anslinger, Doughton, Brown, and McCormack seemed merely to be reinforcing each others' convictions. There was no probing of the government witnesses. In fact, the govern-ment made its case in the House in one session, and the next three sessions were devoted to countering technical objections of the oilseed, birdseed, and hemp industries.11

On the last morning of scheduled hearings, however, the final witness introduced some suspense into these otherwise pro forma proceedings. Dr. William C. Woodward, the bureau's sometime ally, appeared on behalf of the AMA to oppose the bill. Dr. Woodward methodically challenged the validity of each of the assump‘tions upon which the legislation was based, noting again and again that he had no objection to amendment of the Harrison Act. Yet the congressmen were in no mood for the AMA or Dr. Woodward, and they roundly insulted his audacity in daring to question the wis-dom of the bill (an attitude that might not have surfaced had Woodward not been standing alone while his medical colleagues stood on the sidelines).

How Dare You Dissent!

Dr. Woodward objected to H.R. 6385 because he believed that its ultimate effect would be to strangle any medical use of marihuana.

Although there were admittedly few recognized therapeutic appli-cations, the bill, in his view, inhibited further research which might bear fruit. He implied that the bill was designed with this objective in mind. Dr. Woodward was, in fact, quite correct in both respects. Anslinger had desired since 1930 to eliminate any medical use, and the Marihuana Tax Act had exactly that effect for thirty years.

It was not characteristic of Dr. Woodward to raise objections without presenting alternatives. He patiently noted that if federal legislation was considered necessary, it could be achieved without sacrificing medical usage by simply amending the Harrison Act. The bureau had drafted the Marihuana Tax Act in secret12 without consulting him or any other representative of the AMA, and he did not hesitate to point out deficiencies in the bureau's case.

First, he criticized the nature of the testimony in general:

That there is a certain amount of narcotic addiction of an objectionable character no one will deny. The newspapers have called attention to it so prominently that there must be some grounds for their statements. It has surprised me, however, that the facts on which these statements have been based have not been brought before this committee by competent primary evidence. We are referred to newspaper publications concerning the prevalence of marihuana addiction. We are told that the use of marihuana causes crime.

But yet no one has been produced from the Bureau of Prisons to show the number of prisoners who have been found addicted to the marihuana habit. An informal inquiry shows that the Bureau of prisons has no evidence on that point.

You have been told that school children are great users of marihuana cigarettes. No one has been summoned from the Children's Bureau to show the nature and extent of the habit among children.

Inquiry of the Children's Bureau shows that they have had no occasion to investigate it and know nothing particularly of it.

Inquiry of the Office of Education—and they certainly should know something of the prevalence of the habit among the school children of the country, if there is a prevalent habit—indicates that they have had no occasion to investigate and know nothing of it.

Moreover, there is in the Treasury Department itself, the Public Health Service, with its Division of Mental Hygiene. The Division of Mental Hygiene was, in the first place, the Division of Narcotics. It was converted into the Division of Mental Hygiene, I think, about 1930. That particular Bureau has control at the present time of the narcotics farms that were created about 1929 and 1930 and came into operation a few years later. No one has been summoned from that Bureau to give evidence on that point.

Informal inquiry by me indicates that they have had no record of any marihuana or Cannabis addicts who have even been com-mitted to those farms.

The Bureau of the Public Health Service has also a division of pharmacology. If you desire evidence as to the pharmacology of Cannabis, that obviously is the place where you can get direct and primary evidence, rather than the indirect hearsay evidence.13

Woodward noted with regard to the alleged evil effects of the drug, that during the drafting of the Uniform Act, the participants "could not . .. find evidence that would lead it to incorporate in the model act a [marihuana] provision."14 Dr. Woodward also pointed out that there was no evidence to believe there had been an increase in the use of the drug.

Mr. McCORMACK. There is no question but that the drug habit has been increasing rapidly in recent years.

Dr. WOODWARD. There is no evidence to show whether or h not it has been.

Mr. McCORMACK. In your opinion, has it increased?

Dr. WOODWARD. I should say it has increased slightly. News-paper exploitation of the habit has done more to increase it than anything else.15

Dr. Woodward's most pointed attack was directed againk the assumption that federal legislation was needed to control the marihuana habit. He argued that existing state legislation was more than sufficient, if properly enforced, and that if lack of coordina-tion was the problem, that was the FBN's fault. Noting that the FBN already had the authority under its establishing act to "ar-range for the exchange of information concerning the use and abuse of narcotic drugs in [the] states and for cooperation in the institution and prosecution of suits. . . ,"16 he asserted that the bureau had not done its job: "If there is at the present time any weakness in our state laws relating to Cannabis, or to marihuana, a fair share of the blame, if not all of it, rests on the Secretary of the Treasury and his assistants who have had this duty imposed upon them for 6 and more years." 17

Quoting denials of federal responsibility in the 1929 Cummings Report and Anslinger's 1934 submission to the League of Nations, Woodward observed that "it has only been very recently, apparently, that there has been any discovery by the Federal Government of the supposed fact that Federal legislation rather than state legislation is desirable."18 In short, Woodward suggested that the federal legislation was contrived and that it would serve no useful purpose beyond that which could be served by the exercise of leadership in the coordinated enforcement of state laws.

Dr. Woodward also contended that the law would be a useless expense to the medical profession and would be unenforceable as well. Since marihuana grows so freely, and every landowner was a potential "producer," whether wittingly or unwittingly, full enforcement would require inspection of the entire land area of the country, a task which would be unseemly for the federal govern-ment ,to undertake.19 Further, the assumption of federal respon-sibility would exacerbate the "general tendency to evade responsibility on the part of the states, .. . a thing that many of us think ought not to be tolerated." 2°

Finally, Dr. Woodward wondered why, if federal legislation was considered necessary, the Congress did not simply amend the Harrison Act. To the bureau's argument that such a course would be unconstitutional, he inquired how Treasury's counsel could argue that the present bill was constitutional since the technique was identical. Dr. Woodward's own view was that amendment of the Harrison Act would be constitutional and that such a course would dispel the professional objections which he had raised.21

As soon as Dr. Woodward completed his testimony, he was met with objections. First, Congressman Vinson suggested that Wood-ward was not speaking for the AMA, and he engaged the doctor in a contentious dialogue about the impact of a recent AMA Journal editorial which appeared to support the bill.22 Vinson argued that it reflected AMA policy. Woodward contended that it merely para-phrased Anslinger. Then Vinson embarked on a thinly veiled diatribe against the AMA's opposition to New Deal legislation, suggesting that Woodward's position on H.R. 6385 was the kind of obstructionism which he had come to expect from the association?3 When the subject turned to the AMA's position on the Harrison Act, Congressman Cooper joined the fray:

Mr. COOPER. I understood you to state a few moments ago, in answer to a question asked by Mr. Vinson, that you did not favor the passage of the Harrison Narcotic Act, because you entertained the view that the control should be exercised by the States.

Dr. WOODWARD. I think you are probably correct. But we cooperated in securing its passage.

Mr. COOPER. You did not favor it, though?

Dr. WOODWARD. Did not favor the principle; no.

Mr. COOPER. Are you prepared to state now that that act has produced beneficial results?

Dr. WOODWARD. I think it has

Mr. COOPER. You think it has?

Dr. WOODWARD. I think it has.

Mr. COOPER. You appeared before this committee, the Ways and Means Committee of the House, in 1930, when the bill was under consideration to establish the Bureau of Narcotics, did you not?

Dr. WOODWARD. I did.

Mr. COOPER. And at that time, did you not state that "the physicians are required by law to register in one form or another, either by taking out a license or by a system of registration that is provided for in the Harrison Narcotic Act; they are required to keep records of everything they do in relation to the profes-sional and commercial use of narcotic drugs. To that, I think we can enter no fair objection, because I see no other way by which the situation can be controlled."

That was your view then, was it not?

Dr. WOODWARD. It was; and if I may interject, to that—that same method of regulating Cannabis, insofar as it is a medical problem, tying it in with the Harrison Narcotic Act—I think you will find that our board of trustees and house of delegates will [not] object....

Mr. COOPER. .. . [D] o you state now before this committee that there is no difficulty involved—that there is no trouble presented because of marihuana?

Dr. WOODWARD. I do not.

Mr. COOPER. What is your position on that?

Dr. WOODWARD. My position is that if the Secretary of the Treasury will cooperate with the States in procuring the enact-ment of adequate State legislation, as he is charged with doing under the law, and will cooperate with the States in the enforce-ment of the State laws and the Federal law, as likewise he is charged with doing, the problem will be solved through local police officers, local inspectors, and so forth.

Mr. COOPER. With all due deference and respect to you, you have not touched, top, side, or bottom, the question that I asked you. I asked you: Do you recognize that a difficulty is involved and regulation necessary in connection with marihuana?

Dr. WOODWARD. I do. I have tried to explain that it is a State matter.

Mr. COOPER. Regardless whether it is a State or a Federal matter, there is trouble?

Dr. WOODWARD. There is trouble.

Mr. COOPER. There is trouble existing now, and something should be done about it. It is a menace, is it not?

Dr. WOODWARD. A menace for which there is adequate remedy.

Mr. COOPER. Well, it probably comes within our province as to what action should be taken about it. I am trying to get from you some view, if you will be kind enough to give it. To what do you object in this particular bill, in the method that is sought to be employed here?

Dr. WOODWARD. My interest is primarily, of course, in the medical aspects. We object to the imposing of an additional tax on physicians, pharmacists, and others, catering to the sick; to require that they register and reregister; that they have special order forms to be used for this particular drug, when the matter can just as well be covered by an amendment to the Harrison Narcotic Act.

If you are referring to the particular problem, I object to the act because it is utterly unsusceptible of execution, and an act that is not susceptible of execution is a bad thing on the statute books.

Mr. COOPER . I understood you to say a few moments ago, in response to a question that I asked you, that you recognize there is an evil existing with reference to this marihuana drug.

Dr. WOODWARD. I will agree as to that.

Mr. COOPER. Then I understood you to say just now, in response to a question by Mr. Robertson of Virginia, that some of the State laws are inadequate and the Federal law is inade-quate to meet the problem.

Dr. WOODWARD. Yes, sir.

Mr. COOPER. That is true?

Dr. WOODWARD. I think that is clear.

Mr. COOPER. And, as you recall, there are two States that have no law at all?

Dr. WOODWARD. That is the best of my recollection.

Mr. COOPER. Taking your statement, just as you made it here that the evil exists and that the problem is not being properly met by State laws, do you recommend that we just continue to sit by idly and attempt to do nothing?

Dr. WOODWARD. No; I do not. I recommend that the Secre-tary of the Treasury get together with the State people who can enforce the law and procure the enactment of adequate State laws. They can enforce it on the ground.

Mr. COOPER. Years have passed and effective results have not been accomplished in that way.

Dr. WOODWARD. It has never been done.

Mr. COOPER. And you recommend that the thing for us to do is to yet continue the doctrine of laissez-faire and do nothing? Dr. WOODWARD. It has never been done.24

This exchange captures vividly what was at issue. Dr. Woodward was opposed to federal legislation which, in his view, would impose severe burdens without achieving any benefits. The New Deal Congress, on the other hand, was disposed to legislate on any colorably "national" evil, whatever its scope. It could be said, indeed, that the Congress was psychologically habituated to the enactment of federal legislation. Several minutes later Chairman Doughton began:

The CHAIRMAN. If [marihuana's] use as a medicine has fallen off to a point where it is practically negligible, and its use as a dope has increased until it has become serious and a menace to the public, as has been testified here—and the testimony here has been that it causes people to lose their mental balance, causes them to become criminals so that they do not seem to realize right from wrong after they become addicts of this drug—taking into consideration the growth in its injurious effects and its diminution in its use so far as any beneficial effect is concerned, you realize, do you not, that some good may be accomplished by this proposed legislation?

Dr. WOODWARD. Some legislation: yes, Mr. Chairman.

The CHAIRMAN. If that is admitted, let us get down to a few concrete facts. With the experience in the Bureau of Narcotics and with the State governments trying to enforce the laws that are now on the State statute books against the use of this deleterious drug, and the Federal Government has realized that the State laws are ineffective, don't you think some Federal' legislation necessary?

Dr. WOODWARD. I do not.

The CHAIRMAN. You do not.

Dr. WOODWARD. No. I think it is the usual tendency to— —

The CHAIRMAN. I believe you did say in response to Mr. Cooper that you believed that some legislation or some change in the present law would be helpful. If that be true, why have you not been here before this bill was introduced proposing some remedy for this evil?

Dr. WOODWARD. Mr. Chairman, I have visited the Commis-sioner of Narcotics on various occasions--

The CHAIRMAN. That is not an answer to my question at all. Dr. WOODWARD. I have not been here because--

The CHAIRMAN. You are here representing the medical asso-ciation. If your association has realized the necessity, the impor-tance of some legislation—which you now admit—why did you wait until this bill was introduced to come here and make mention of it? Why did you not come here voluntarily and suggest to this committee some legislation?

Dr.WOODWARD. I have talked these matters over many times with the --

The CHAIRMAN. That does not do us any good to talk matters over. I have talked over a lot of things. The States do not seem to be able to deal with it effectively, nor is the Federal Govern-ment dealing with it at all. Why do you wait until now and then come in here to oppose something that is presented to us. You propose nothing whatever to correct the evil that exists.

Now, I do not like to have a round-about answer, but I would like to have a definite, straight, clean-cut answer to that question.

Dr. WOODWARD. We do not propose legislation directly to Congress when the same end can be reached through one of the executive departments of the Government.

The CHAIRMAN. You admit that it has not been done. You said that you thought some legislation would be helpful. That is what I am trying to hold you down to. Now, why have you not proposed any legislation? That is what I want a clean-cut, definite, clear answer to.

Dr. WOODWARD. In the first place, it is not a medical addic-tion that is involved and the data do not come before the medical society. You may absolutely forbid the use of Cannabis by any physician, or the disposition of Cannabis by any pharmacist in the country, and you would not have touched your Cannabis addiction as it stands today, because there is no relation between it and the practice of medicine or pharmacy. It is entirely out-side of those two branches.

The CHAIRMAN. If the statement that you have just made has any relation to the question that I asked, I just do not have the mind to understand it; I am sorry.

Dr. WOODWARD. I say that we do not ordinarily come directly to Congress if a department can take care of the matter. I have talked with the Commissioner, with Commissioner Anslinger. The CHAIRMAN. If you want to advise us on legislation, you ought to come here with some constructive proposals, rather than criticism, rather than trying to throw obstacles in the way of something that the Federal Government is trying to do. It has not only an unselfish motive in this, but they have a serious re sponsibility.

Dr. WOODWARD. We cannot understand yet, Mr. Chairman, why this bill should have been prepared in secret for two years without any intimation, even, to the profession, that it was being prepared.

The CHAIRMAN. Is not the fact that you were not consulted your real objection to this bill?

Dr. WOODWARD. Not at all.

The CHAIRMAN. Just because you were not consulted? Dr. WOODWARD. Not at all.

Mr. CHAIRMAN. No matter how much good there is in the proposal?

Dr. WOODWARD. Not at all.

The CHAIRMAN. This is not it?

Dr. WOODWARD. Not at all. We always try to be helpful.25

After accusing Dr. Woodward of obstructionism, evasiveness, and bad faith, the committee did not even thank him for his testi-mony. When the Senate Finance Committee conducted hearings on the bill—now styled H.R. 6906—two months later, Dr.Woodward must have decided to spare himself the grief of a personal appear-ance. He submitted instead a short letter which stated the AMA's reasons for opposing the bill. 26

Both committees reported the bill favorably despite Woodward's objections. The Ways and Means report raised the FBN assertions against marihuana to the level of congressional findings:

Under the influence of this drug the will is destroyed and all power of directing and controlling thought is lost. Inhibitions are released. As a result of these effects, it appeared from testi-mony produced at the hearings that many violent crimes have been and are being committed by persons under the influence of this drug. Not only is marihuana used by hardened criminals to steel them to commit violent crimes, but it is also being placed in the hands of high-school children in the form of marihuana cigarettes by unscrupulous peddlers. Cases were cited at the hearings of school children who have been driven to crime and insanity through the use of this drug. Its continued use results many times in impotency and insanity. 27

Congressional "Deliberation" and Action

The marihuana "problem" and the proposed federal cure went virtually unnoticed by the general public. Having failed to arouse public opinion on any significant scale through its educational campaign, the Bureau of Narcotics nevertheless pushed the proposed legislation through congressional committees. The committee mem-bers were convinced by inaccurate, unscientific evidence that federal action was urgently needed to suppress a problem that was no greater and probably less severe than it had been in the preced-ing six years when every state had passed legislation to suppress it. The committee was also convinced, incorrectly, that the public was aware of the evil and that it demanded federal action.

The debate on the floor of Congress illustrates the nonchalance of the legislators. The bill passed the House of Representatives in the very late afternoon of a long session. Many members were un-familiar either with marihuana or with the purpose of the act. When file bill came to the House floor on 10 June 1937, one congressman objected to considering the measure at such a late hour:

Mr. DOUGHTON. I ask unanimous consent for the present consideration of the bill [H.R. 69061 to impose an occupational excise tax upon certain dealers in marihuana, to impose a trans-fer tax upon certain dealings in marihuana, and to safeguard the revenue therefrom by registry and recording.

The Clerk read the title of the bill.

Mr. SNELL. Mr. Speaker, reserving the right to object, and notwithstanding the fact that my friend, Reed, is in favor of it, is this a matter we should bring up at this late hour of the after-noon? I do not know anything about the bill. It may be all right and it may be that everyone is for it, but as a general principle, I am against bringing up any important legislation, and I sup-pose this is important, since it comes from the Ways and Means Committee, at this late hour of the day.

Mr. RAYBURN. Mr. Speaker, if the gentleman will yield,Imay say that the gentleman from North Carolina has stated to me that this bill has a unanimous report from the committee and that there is no controversy about it.

Mr. SNELL. What is the bill?

Mr. RAYBURN. It has something to do with something that is called marihuana. I believe it is a narcotic of some kind. Mr. FRED M. VINSON. Marihuana is the same as hashish.

Mr. SNELL. Mr. Speaker, I am not going to object but I think it is wrong to consider legislation of this character at this time of night.28

On 14 June, when the bill finally emerged on the House floor, four congressmen in one way or another asked that the proponents explain the provisions of the act. Instead of a detailed analysis, they received a statement of one of the members of the Ways and Means Committee which repeated reflexively the lurid criminal acts Anslinger had attributed to marihuana users at the hearings. After less than two pages of debate, the act passed without a roll call. 29 When the bill returned as amended from the Senate, the House considered it again and adopted as quickly as possible the Senate suggestions, which were all minor.3° The only question was whether the AMA agreed with the bill. Congressman Vinson not only said they did not object, but he also claimed that the Bill had AMA support. After turning Dr. Woodward's testimony on its head, he also called him by another name—Wharton.31

The act passed Congress with little debate and even less public attention. Although the Federal Bureau of' Narcotics had not sought legislation, the bureau's efforts on behalf of the Uniform Narcotic Drug Act had created a climate of fear which provoked insistent cries for a federal remedy, particularly by a few state law enforcement agents hoping to get federal support for their activities. As a result, the law was tied neither to scientific study nor to en-forcement need. The Marihuana Tax Act was hastily drawn, heard, debated, and passed. It was a paradigm of the uncontroversial law.

Notes

1. House, Hearings on H.R. 6385, p. 30.

2. Ibid., pp. 32-42.

3. U.S., Congress, Senate, Finance Committee Subcommittee, Hearings on H.R.

6906, 75th Cong., 1st sess., 1937, pp. 11-14 (hereafter cited as Senate, Hearings on H.R. 6906).

4. House, Hearings on H.R. 6385, pp. 48-52.

5. Ibid., pp. 32-37.

6. Senate, Hearings on H.R. 6906, pp. 14-15.

7. Ibid.

8. See generally H. S. Becker, Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance (London: Free Press of Glencoe, 1963).

9. Senate, Hearings on H.R. 6906, p. 16.

10. House, Hearings on H.R. 6385, p. 26.

11. Ibid., pp. 59-65, 67-86.

12. Ibid., pp. 87-88.

13. Ibid., p. 92.

14. Ibid., p. 100.

15. Ibid., p. 118. See also pp. 117, 120.

16. Act of 14 June 1930, ch. 488, 46 Stat. 585.

17. House, Hearings on H.R. 6385, p. 93.

18. Ibid., p. 94.

19. Ibid., pp. 94-95.

20. Ibid., p. 95.

21. Ibid., p. 97.

22. Ibid., pp. 100-102.

23. Ibid., pp. 102-5.

24. Ibid., pp. 105-6, 110.

25. Ibid., pp. 115-16.

26. Senate, Hearings on H.R. 6906, pp. 33-34.

27. U.S., Congress, House, Committee on Ways and Means, 75th Cong., 1st sess., 11 May 1937, H. Rept. 292, pp. 1-2.

28. 81 Congressional Record (1937), p. 5575.

29. Ibid., pp. 5689-92.

30. Ibid., pp. 7624-25.

31. Ibid., p. 7625.

|