4 THE RISE OF THE KILLER WEED

| Books - The Strange Career of Marihuana |

Drug Abuse

4 THE RISE OF THE KILLER WEED

The 1930s witnessed the consolidation of an image of marihuana as a "killer weed," the development of a consensus among those at all interested that the drug was a menace, and the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act. In this chapter we shall examine how all this came to pass.

INITIAL UNCERTAINTY

Prior to the 1930s, among those few who considered the issue, there was no consistent image of marihuana use and the problems it posed. The seven Readers' Guide articles before 1931 show few commonalities of perception and theme. Only three are concerned with nonmedical marihuana use in the United States. The other four include a clinical report by a physician of his own reactions to cannabis, an appropriately lurid account of "hachisch eating" in an unidentified European or Near Eastern setting, an editorial on the findings of the Indian Opium and Hemp commissions, and a discussion by the governor of the Sinai Province of Egypt on hashish smuggling in the area.'

There was, moreover, no one name for the drug itself. By the mid-1930s, it was known generally as "marihuana," but until then it had several identities. As a medical preparation and an object of scientific interest, it was "cannabis"; as an intoxicant found in Mexico and along the Texas border, it was "marihuana"; and as an Eastern drug identified with Arabs and Indians, it was "hashish" (or "hachisch" or "hash eesh") or "Indian hemp."

The multiplicity of terms implies that the drug had no settled social identity even in the accounts of domestic American use. To Alfred Lewis, a Hearst reporter and well-known writer on the Southwest, it was "marihuana" and very Mexican. To Carlton Simon, chief of New York City's narcotics division, it was "hash eesh," smuggled in by Turks and East Indians and rapidly becoming the latest "narcotics evil." In a 1926 Literary Digest account, the drug was both "hasheesh" and "marihuana."

Assessments of the drug's dangers also varied greatly. Some articles expressed no worry at all. The 1895 Spectator editorial applauded the Indian Hemp Commission's conclusion that the moderate use of hemp was harmless (and excessive use less dangerous than a similar indulgence in alcohol) and added its own dictum that the real problem lay not in the drug, but in the gluttony of the user. The 1926 Literary Digest article showed a similar lack of concern in reporting the Department of Agriculture's judgment that marihuana use "simply causes temporary elation, followed by depression and heavy sleep."

Other articles noted some negative or dangerous effects but did not generally condemn the drug. In his 1893 clinical report, Edward W. Scripture succinctly noted some "disagreeable effects," but managed, nevertheless, to regard cannabis simply as an object of scientific interest. E. B. Mawer described the widely unpredictable results of "hachisch eating" but concluded that "one may occasionally use it without any marked ill effect." Even Scudamore Jarvis, while describing his own efforts to quash hashish smuggling in the Sinai, regarded the drug as a "mild form of narcotic," which was dangerous only after "constant use."

Still other articles took a more negative view. Lewis recounted how marihuana made the user uncontrollably violent, and Simon described it as an unmitigated evil.

SOUTHWEST-NEW ORLEANS STEREOTYPE

The lack of consistency in subject matter, in the assessment of marihuana's dangers, and even in the names used to describe the drug suggests that for much of the first three decades of the century, there was no generally accepted conception of marihuana either as a drug or as a social problem. In the Southwest and New Orleans, however, such a unified image—tying together marihuana, violence, and Mexican laborers and other lower-class groups—had existed from the early 1910s.

Marihuana use, as we have shown in the previous chapter, was never a major issue in the Southwest at the time, nor was it an important part of anti-Mexican racial stereotypes. Mexican laborers, however, often were perceived by Anglos as "criminal types": They were noted for carrying knives and being drunk and disorderly. When marihuana was discussed, it was usually associated with Mexicans. As a result, marihuana also became associated with violence, a "killer weed."

The idea that marihuana use made Mexican laborers violent was well established among upper-strata Mexicans in both Mexico and the United States in the early 1900s.2 As Mexicans moved into the United States to take the cheap laboring jobs available in fields from Texas to California and as far north as Idaho and Montana, they brought marihuana with them. The Mexican-marihuanaviolence image then followed. Lewis's 1913 Cosmopolitan short story concerns the ill-fated adventures of an errant Harvard graduate who is attracted to Mexicans and marihuana in a border town and ultimately becomes so violent that he must be killed in self-defense. Lewis's narrator is quite clear that marihuana is a Mexican drug, and he is no less clear that marihuana induces violence and that Mexicans are worthless.

Once old marihuana wrops its tail about your intellects, you becomes voylent an' blood-hungry, an' goes on the onaccountable war-path, mighty deemoniac. . . .

Mexicans. . . ain't of no use in this world but to shoot at when you wants to unload an' clean your gun.'

The image of marihuana presented by Lewis was common whenever the drug was discussed in the Southwest in the 1910s and 1920s. Reports on marihuana by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1917 and by U.S. Canal Zone authorities in 1925 cite numerous accounts by law enforcement officials and newspapers in the Southwest regarding the connections between marihuana, Mexicans, and violence. The brief legislative discussions that preceded the passage of antimarihuana legislation in numerous southwestern and western states often made pointed references to the Mexican origins and violent effects of the drug. California crime studies in the 1920s noted the high rates of crime and delinquency among Mexicans, and the state's narcotics reports identified marihuana as a Mexican drug.'

The perception of marihuana as violence-producing also developed in places where Mexicans were not identified as the only users, principally in New Orleans. As we have noted, New Orleans was perhaps the one place in the 1920s and 1930s where marihuana was an issue of some importance. It is not surprising, then, that several local officials and citizens wrote pieces describing the evils of the drug: Frank Gomila, New Orleans commissioner of public safety; Eugene Stanley, New Orleans district attorney; and A. E. Fossier, a local physician. Their work had immense impact on the public discussion of marihuana in the 1930s and subsequent decades.' ;,5

The authors agreed that marihuana made the user violent. Indeed their perceptions are summed up neatly by the title of Stanley's article—"Marihuana as a Developer of Criminals." They did not, however, identify Mexicans as the sole users. Fossier and Stanley, whose articles were virtually identical, described the user simply as of the "criminal class." Gomila asserted that marihuana dealers were "Mexicans, Italians, Spanish-Americans, drifters from ships" and that users included dock workers and sailors, Negroes ("Practically every Negro in the city can give a recognizable description of the drug's effects"), Mexicans, and "vicious characters." The New Orleans image of marihuana and violence, in short, developed in tandem with a perception of the users as either members of racial minorities or as lower- and working-class whites.6

In the early 1930s, the New Orleans and Southwest image of marihuana use found its way into the discourse of federal law enforcement officials, and by 1935 it dominated media discussions of the drug as well. Prior to that time, marihuana had received little federal attention, and when it had, the Mexican-marihuanaviolence connection was not evident. In 1929, both the federal act establishing "narcotics farms" for treating addicts and the surgeon general's report referred to the drug as "Indian hemp," not "marihuana." The surgeon general's discussion in particular seemed to draw its image of the drug solely from various Oriental legends and thus presented a dual image of its effects. From legends of amok Malays and Islamic assassins came an image of crime and violence; from stories of decadent, declining civilizations came an image of passivity and deterioration.7

In contrast, the 1931 "Report on Crime and the Foreign Born" by the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement (the Wickersham Commission) reflected but did not consistently endorse the New Orleans-Southwest stereotype of Mexicans-violencemarihuana. The report was concerned with whether or not the foreign born had higher crime rates than native-born white Americans. A review of official crime reports satisfied the researchers that nearly all foreign-born groups had lower crime rates than native-born whites. The exception was Mexicans, whose official crime rates were exceedingly high, and the report spent considerable time pondering this matter. Although it concluded that the high crime rates had more to do with social conditions, differential arrest rates, and cultural differences than with an inherent Mexican tendency to violence, the very attention given the Mexican-violence issue attests to the strength of the stereotype. Indeed, the researchers documented the prevalence of the prejudice with quotes from judges and police officials in areas with high Mexican populations.

The report also noted that Mexicans were tied closely to drug use, particularly marihuana use. Mexicans, it reported, constituted only 2.7 percent of all offenders in state and federal prisons, but 27.1 percent of all drug offenders. Marihuana was described as "a drug the use of which has spread with the dispersion of Mexican immigrants" and whose "use is widespread throughout Southern California among the Mexican population."8

Finally, marihuana was described as a violent drug in a citation from a publication of the California State Narcotics Committee: "If continued, the drug develops a delirious rage, causing the smoker to commit atrocious crimes."9

It was the New Orleans-Southwest stereotype that insinuated itself into the perceptions of federal narcotics officials. The Wickersham study and the 1917 Department of Agriculture investigation made their way into the bureau's files, and a New Orleans FBN agent forwarded Stanley's article to his superiors in Washington.10 FBN Commissioner Harry Anslinger reported that his first perceptions of marihuana were based reports from southwestern and western states where there was concern about the behavior of Mexicans who "sheriffs and local police departments claimed got loaded on the stuff and caused a lot of trouble, stabbings, assaults, and so on.11

It is not surprising, then, that when federal narcotics officials first referred to marihuana, they described its users as "Spanish-speaking" and "Latin Americans." 12 Several years later, when the FBN began publicizing the effects of the drug, it stressed violent crime.13

In short, a stereotype connecting marihuana use, Mexican laborers and other lower-class groups, and violence developed in the Southwest and New Orleans in the 1910s and 1920s. This stereotype made its way into the federal bureaucracy through clear avenues of diffusion and from there into the national media. By the 1930s, whenever the drug was discussed, the intoxicating products of the hemp plant were clearly identified as "marihuana," which was perceived as a violence-inducing drug, first used in the United States by Mexican laborers and other marginal social groups. When the drug was seen to be spreading to "school children" in the mid-1930s, the Mexican component of the image became vestigial. Marihuana's reputation as a violence-producing weed, however, remained strong. Detached from its original social moorings, the image of marihuana as a "killer weed" became the mainstay of the bureau's case against the drug and through the bureau's efforts came to dominate virtually all discussion of marihuana for a considerable time.

THE BUREAU TAKES ON MARIHUANA

Once the bureau decided to act on marihuana, therefore, it had a ready-made image of the drug to disseminate. The bureau's decision, however, was the result of a complex set of events, and its relationship to marihuana was anything but simple or constant.

Prior to 1929, federal narcotics officials virtually ignored marihuana. Their semiannual and annual reports for 1926 through 1928 do not even mention it. In 1928, however, Congressman James O'Connor of New Orleans requested the inclusion of marihuana in the Harrison Act, and the next year, Senator Morris Sheppard of Texas proposed a bill to add the drug to the Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act. These actions, coupled with the surgeon general's report and the new federal classification of marihuana as a narcotic, brought the drug to the attention of narcotics officials.''14

Their initial official response, however, was cold indifference. The narcotics reports for 1929 and 1930 presented a perfunctory assessment of the drug and showed no recognition of its use bothering anyone. They noted the erstwhile domestic hemp industry, the widespread wild growth of the plant, the modest imports for legitimate medical use and occasionally for nonmedical use, and the availability of treatment for addicts at the federal narcotics farms. Finally, the reports briefly discussed marihuana "abuse":

The abuse of this drug consists principally in the smoking thereof, in the form of cigarettes for the narcotic effect. This abuse of the drug is noted particularly among the Latin-American or Spanish-speaking population. The sale of cannabis cigarettes occurs to a considerable degree in states along the Mexican border and in cities of the Southwest and West, as well as in New York City, and in fact wherever there are settlements of Latin Americans.'15

There was no alarm and hardly a hint that there was a problem requiring the intervention of the fledging Federal Bureau of Narcotics. In the reports for 1931 through 1934, the bureau's official tone became defensive; rather than simply ignoring any marihuana problem, it explicitly denied that there was one. In 1930, the bureau had been content simply to note the possibility of illicit imports; in 1931, it took pains to argue that these imports were minuscule and that federal controls were not yet needed. It also argued that the publicity given to the drug by unnamed "newspaper articles" was exaggerated.

A great deal of public interest has been aroused by newspaper articles appearing from time to time on the evils of the abuse of marihuana, or Indian hemp, and more attention has been focused upon specific cases reported of the abuse of the drug than would otherwise have been the case. This publicity tends to magnify the extent of the evil and lends color to an inference that there is an alarming spread of the improper use of the drug, whereas the actual increase in such use may not have been inordinately large.'16

The bureau's official reluctance to regard marihuana use as a problem requiring immediate federal attention is interesting in light of the claims of the Anslinger and Mexican hypotheses. Had the bureau's eventual concern with marihuana derived simply from local political pressure (as the Mexican Hypothesis suggests) or from a moralistic desire to suppress a vice (as some versions of the Anslinger Hypothesis argue), it would have acted in the early 1930s. Its reports from those years clearly show that it sensed pressure for a national law, and Commissioner Anslinger personally regarded marihuana use as a vice requiring federal attention. From his first year as head of the FBN, his correspondence advocated eventual national controls." The FBN, however, was neither a moral-crusading, expansion-seeking bureaucracy nor a simple pawn of external political pressure. It was primarily an organization attempting to survive in a basically inhospitable environment, and it did so by strictly limiting its purview. In a sense, it was thrice chastened—first by the failure of Prohibition, second by the court challenges to the Harrison Act, and third by the heavy weight of the Depression.

Commissioner Anslinger and many of the bureau's other top officials had been employees of the Prohibition Bureau, when it had had the responsibility for narcotics law enforcement in the 1920s. They thus had had a close look at the failure of alcohol control and had come away with a set of powerful lessons: Federal narcotics officials should not directly meddle in the lives of private citizens or seek to control any but the most clearly dangerous drugs. If they did, they risked fomenting public discontent and undermining their own legitimacy.18

The judicial history of the Harrison Act also predisposed the bureau to be circumspect in its activities. The Harrison Act was formally a revenue measure that sought to control narcotics by taxing transfers between registered parties and forbidding all transfers to those ineligible to register (virtually everyone but drug companies, physicians, and pharmacists). Between 1915 and 1930, the U.S. Supreme Court had been called on several times to interpret the act's intent." In a few of these cases, the constitutionality of a tax law forbidding transfers of a taxed substance had become an issue, especially when the provision was used to prosecute physicians attempting to provide opiate addicts with maintenance doses of their drug. Although the act was never overturned, the bureau was reluctant to add a new drug to it or do anything else that could occasion yet another court challenge. The problems involved were discussed extensively by narcotics officials after the 1929 surgeon general's report on marihuana and were officially analyzed at the 1937 House hearings on the Marihuana Tax Act.20

Finally, the Bureau was hemmed in by the Depression. It faced the prospect of years of minimal budgets that could not support expanded activities. Indeed, its budget reached a peak of $1.7 million for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1933, and declined thereafter.2'

Federal control of marihuana, moreover, presented its own special problems; in the early 1930s, no one could find a constitutional way to include it in either the Harrison Act or the Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act. Since the former used the federal taxing power to control drug use, its constitutionality was based on the assumption that it generated significant revenue. By 1929, however, marihuana had virtually no medical uses and hence there was little licit trade to be taxed. The Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act used the federal power over foreign commerce to control domestic drug use by employing the presumption that possession of a drug implied illegal importation. Marihuana, however, was grown largely domestically, so the presumption of importation would have been irrational and hence unconstitutional. Furthermore, any effort to control marihuana evoked opposition from pharmaceutical companies, the hemp industry, and the medical profession.22

For all these reasons, the bureau in the early 1930s attempted to limit its responsibility for day-to-day narcotics enforcement and to resist proposals for federal marihuana legislation. All things considered, it was often a resolutely reticent organization, not an aggressively expansionistic one. Its strategy was to have the states handle marihuana and deal with small-time narcotics offenders, while it made general policy and took care of large-scale trafficking.

The bureau sought to accomplish this governmental division of labor by getting the states to pass the Uniform Narcotic Drugs Act. The act had been under consideration for some seven years by a committee appointed by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, when Commissioner Anslinger led the newly created FBN into the drafting process in 1931. He initially urged the inclusion of marihuana in the act but backed down in response to opposition from pharmaceutical companies, physicians, and the hemp industry. A final draft of the act, with a marihuana provision included only as a supplement, was approved in late 1932.

The bureau immediately began to lobby for state adoption of the act by sending its agents directly to legislators and by enlisting the help of sympathetic organizations—the Women's Christian Temperance Union, the World Narcotic Defense Association, the General Federation of Women's Clubs, and the Hearst press. Its efforts met with little success initially. By the end of 1934, only ten states had passed the act; opponents effectively pointed to its expense, its red tape, and its pretensions to control the medical profession and the pharmaceutical industry.

In response to this impasse, the bureau changed the thrust of its arguments and reversed its stand on the marihuana problem: Rather than insisting that the extent of marihuana use was exaggerated, it began to publicize the marihuana "menace" in its arguments for the Uniform Narcotic Drugs Act. The reversal is reflected in the bureau's reports for 1935 and 1936:

A problem which has proved most disquieting to the Bureau during the year is the rapid development of a widespread traffic in Indian hemp, or marihuana, throughout the country."

The rapid development during the past several years, particularly during 1935 and 1936, of a widespread traffic in cannabis, or marihuana, as it is more commonly known in the United States, is regarded with much concern by the Bureau of Narcotics. Ten years ago there was little traffic in this drug except in parts of the Southwest. The weed now grows wild in almost every State in the Union, is easily obtainable, and has come into wide abuse."

The emphasis on the marihuana menace appears to have been successful. Within a year, eighteen additional states had adopted the act, and those without previous legislation included the marihuana provision. At the same time, however, it undermined the bureau's effort to deflect pressure for federal controls. The modest increase in the attention given to marihuana as a result of the bureau's propaganda stimulated new demands for federal legislation and broke down bureaucratic resistance. In 1935, Senator Carl Hatch and Congressman John Dempsey of New Mexico introduced bills to prohibit the shipment and transportation of marihuana in interstate and foreign commerce. The bureau readied the usual objections, but this time it was overruled by the Treasury Department.

Consequently, by early 1936 the bureau had begun to search for an appropriate piece of legislation. Noting a recent Supreme Court decision upholding the National Firearms Act, which attempted to prohibit sales of machine guns by placing a $200 tax on each transfer, it settled on what would ultimately become the Marihuana Tax Act in early 1937: a proposal to place a prohibitive $100 per ounce tax on all sales of marihuana to nonmedical users, thus avoiding the constitutional objections to the Harrison Act.

Thus, the bureau became concerned with the marihuana problem and began to press for a federal law in a circuitous, paradoxical manner. Its general strategy was to survive in an unsupportive environment by strictly limiting its purview and not taking on any enforcement activities that might destroy its legitimacy or strain its resources. To these ends, it sought to make the states take responsibility for marihuana control as well as for day-to-day narcotics enforcement in general. Its efforts took the form of lobbying for state adoption of the Uniform Narcotic Drugs Act. To secure passage of this act, however, it had to conjure up the specter of a marihuana "menace." The added publicity given the drug made federal controls appear all the more necessary. In short, the bureau's efforts to avoid federal marihuana controls eventually led to its having to embrace them.

THE BUREAU'S CONSENSUS: MENACE, VIOLENCE, AND YOUTH

Once the bureau decided to act, it did so with little reserve, and its reticence gave way to a moral crusading fervor. Its antimarihuana publicity effort, though minuscule in the wider scheme of things, dominated public discussion of marihuana in the mid-1930s. Policymakers and the media faithfully adopted the bureau's image of marihuana, repeating the bureau's examples of marihuana-related violence and ignoring the data that the bureau chose to ignore.

The result was a striking consensus among those who discussed the drug. Marihuana was believed to be not just dangerous but a menace. Its myriad effects on consciousness were said to lead in various ways to a maniacal frenzy in which the user was likely to commit all kinds of unspeakable crimes. Users were identified both as Mexicans, who were the original users, and as youth to whom the drug was spreading. Concern focused on what the drug did to the latter group. High-school students were seen as the innocent victims of a drug that ultimately turned them into the worst kinds of criminals and ruined their lives. Indeed, the titles of articles from the period tell the whole story: "Marihuana Menaces Youth," "Marihuana: Assassin of Youth," "Youth Gone Loco," and "One More Peril for Youth." 25

We can understand this consensus by looking at its various components—menace, violence, and youth—and by examining the nature of the bureau's hegemony.

The Menace

By the time they testified at the House hearings on the Marihuana Tax Act, federal narcotics officials were claiming that the whole nation was threatened by the marihuana "menace." Noting that "leading newspapers" had "recognized the seriousness of this problem," Clinton Hester, assistant general counsel for the Department of Treasury, opened the House hearings on the Marihuana Tax Act in April of 1937 by citing the following editorial from the Washington Times:

The marihuana cigaret is one of the most insidious of all forms of dope, largely because of the failure of the public to understand its fatal qualities. . . .

The nation is almost defenseless against it, having no Federal laws to cope with it and virtually no organized campaign for combatting it."

Commissioner Anslinger underlined his portrayal of the drug as a "national menace" by contrasting it with opium, which could be both beneficial and harmful:

But here we have a drug that is not like opium. Opium has all of the good of Dr. Jekyll and all of the evil of Mr. Hyde. This drug is entirely the monster Hyde.27

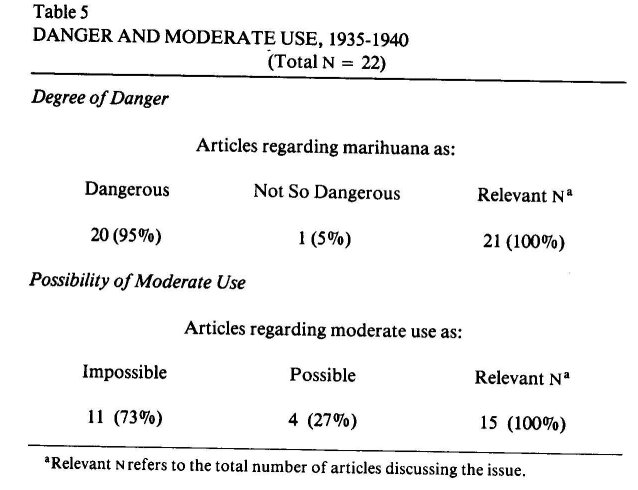

The House Ways and Means Committee accepted Anslinger's portrait of marihuana and received with hostility the testimony of William Woodward, the AMA representative, who minimized the extent of the problem. Anslinger's view also dominated periodical articles during the period. All but one of the twenty-one articles that discussed the matter agreed that the drug was dangerous.

Marihuana was said to be a "serious menace" and "more dangerous than cocaine or heroin" by Scientific American and a "dangerous and devastating narcotic" by Newsweek." The articles were almost equally as adamant that safe or moderate use of the drug was impossible; eleven of the fifteen articles that referred to the issue took this position. Indeed, only one article from the period, a 1936 Literary Digest piece, conveyed the sense that marihuana was fairly innocuous." It described "sensuous pleasure" as the "beginning and end" of marihuana use and reported that Harlem reefer parties were generally affable and peaceful in contrast to the average alcohol party (see Table 5).

Violence

Although marihuana was said to produce a myriad of effects and was condemned as "unpredictable" in this regard, violence was the mainstay of arguments against the drug. In contrast to the claims of passivity that would dominate antimarihuana beliefs in the 1960s, marihuana was said to produce aggressive actions against self and others. Earl and Robert Rowell, in their 1939 antimarihuana tract, captured this image quite well: "While opium Kills ambition and Deadens initiative, marihuana incites to immorality and crime.'"° In the 1960s, marihuana would be said to "Kill ambition" and "Deaden initiative."

In one of its first detailed descriptions of the effects of marihuana, the FBN enumerated the drug's various effects on consciousness—euphoria, stimulation of the imagination, kaleidoscopic visions, distortions of time and space perception—and then argued:

The principal effect of the drug is upon the mind which seems to lose the power of directing and controlling thought. Its continued use produces pronounced mental deterioration in many cases. Its more immediate effect apparently is to remove the normal inhibitions of the individual and release any antisocial tendencies which may be present. Those who indulge in its habitual use eventually develop a delirious rage after its administration, during which time they are, temporarily at least, irresponsible and prone to commit violent crimes."

While mental deterioration received no further attention, the violence theme was supported by quotes from appropriate authorities and by examples of "marihuana crimes."

At the House hearings, a large number of dangers again were noted, including unpredictability, degeneration of the brain, insanity, distortions of perception, automobile accidents, addiction, and death. Indeed, the only effect not imputed to marihuana was progression to harder drugs. The stepping-stone claim, which became the basis of the bureau's case against marihuana in the 1950s, was specifically denied by Anslinger.

Mr. Dingell. I am just wondering whether the marihuana addict graduates into a heroin, an opium, or a cocaine user.

Mr. Anslinger. No sir; I have not heard of a case of that kind. I think it is an entirely different class. The marihuana addict does not go in that direction."

The hearings clearly stressed violence, however. Anslinger argued that marihuana use stimulated violent behavior by dissolving moral restraints, destroying the ability to judge right and wrong, stimulating grandiose fantasies, and making the user highly suggestible. He supported his case with a half-dozen examples of marihuana-related crimes, a study (from Stanley) that concluded that 125 of 450 inmates in a New Orleans jail were "marihuana addicts," and several Old World marihuana legends from Fossier and Stanley: that hashish was used by the Islamic sect of Assassins to fortify themselves for political murders, that it made the Malays run "amok," and that it was the "nepenthe" that Homer said "made men forget their homes." Violence was also the central theme of the three articles (including the Stanley and Gomila pieces) submitted as exhibits to the committee and two of the four letters submitted." No other allegation received even a fraction of this attention.

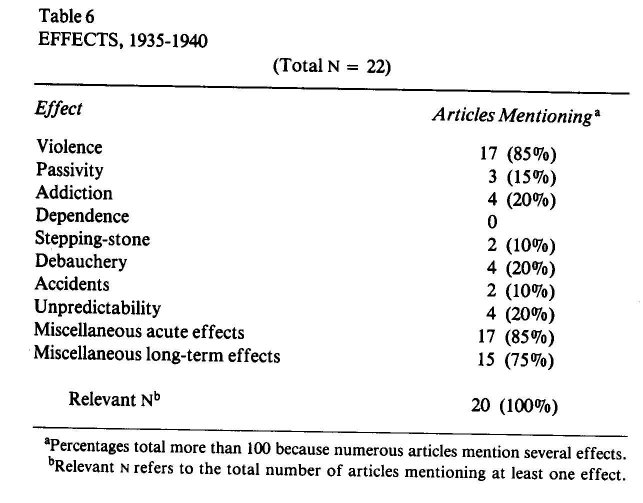

Violence was the mainstay of periodical articles during the era also (see Table 6). Eighty-five percent of the twenty Readers' Guide articles that discussed effects mentioned violence. In contrast, only a few referred to addiction, passivity, stepping-stone, accidents, or other specific effects. More importantly, violence was virtually the only theme that received detailed attention. The claim was discussed at length and was buttressed by various legends and alleged cases of marihuana-induced crime.

We cannot adequately appreciate the importance of the violence claim in discussions of marihuana in the late 1930s, however, simply by noting how often the allegation was mentioned. Violence was not simply quantitatively predominant; it also provided the basis of the gestalt that organized perceptions of both the user and use.

Violence was seen not simply as the major effect of marihuana use but as the essential characteristic of the user as well. When periodicals described the user, they pictured either a violent fiend or an innocent victim turned violent fiend. None described him as either normal or essentially withdrawn and passive. Marihuana users were "criminals, degenerates, maniacs" in the words of Survey Graphic and Forum and Century.34

The violence claim also was a way of conceptually organizing and understanding the many other effects imputed to marihuana; each was primarily seen as a way in which marihuana made the user violent. As the 1936 FBN report put it, marihuana use generated violence by removing normal inhibitions and releasing antisocial tendencies. This twin theme of irresistible impulses and destruction of the will pervaded the literature." In a 1937 article Anslinger restated this proposition in a way that linked violence to insanity:

Addicts may often develop a delirious rage during which they are temporarily and violently insane; . . . this insanity may take the form of a desire for self-destruction or a persecution complex to be satisfied only by the commission of some heinous crime."

The persecution complex mentioned by Anslinger was said by others to arise from the delusions and hallucinations brought on by the drug. In his confusion, a user was likely to perceive imaginary threats from others and even fear that his best friend was out to kill him. He would naturally turn to violence to protect himself. Those not subject to delusions of persecution might be prone to "acute erotic visions," which would lead them to commit forcible rape."

Even the most elementary effects of marihuana on consciousness took on a sinister cast. Simple distortions of time and space perception and disturbances of connected thought were said to confuse the mind in such a way that the "slightest impulse or suggestion carries it away." Heightened suggestibility itself was also regarded as a cause of violence, because it was used by "leaders of gangs and criminals" to lure the innocent into crime."

In short, nearly every effect imputed to marihuana was also linked to violence and was interpreted in its light. Insanity, destruction of the will, suggestibility, distortions of perception, and alterations of consciousness all carried the connotations of violence and crime. The image of the violent criminal tied these disparate effects together and gave them coherence.

From Mexicans to Youth

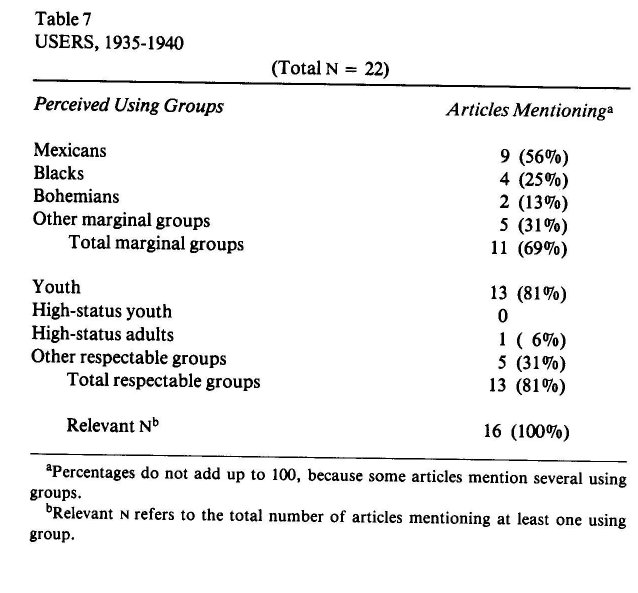

The late 1930s had a dual image of the user. He was said to be on the one hand a Mexican or Spanish-speaking laborer, a black, or bohemian, or a member of the criminal classes—all low-status groups—and on the other hand, a youth of indeterminate social stratum. Eleven of the sixteen periodical articles that discussed the user's social identity mentioned one or more low-status groups, usually Mexicans, while thirteen mentioned youth or school children or high-school students (see Table 7).

The emphasis, however, was clearly on youth. The concern was with what marihuana was doing to young people, not to Mexicans. "It is the useless destruction of youth which is so heartbreaking to all of us," said Anslinger." While Mexicans were directly or indirectly identified as the source of the drug, they were then largely ignored. There were hardly any references to violent, degenerate Mexicans.

The FBN report for 1933 was the last to identify Spanish-speaking persons as marihuana users and the first to note youthful use: "A disconcerting development in quite a number of states is found in the apparently increasing use of marihuana by the younger element in the larger cities."4° The concern with youthful use continued throughout the 1930s.

Concern for the youthful user also dominated the Marihuana Tax Act hearings.

[Marihuana] is now being used extensively by high-school children.. . . The fatal marihuana cigarette must be recognized as a deadly drug and American children must be protected against it. . . . The great majority of indulgers are ignorant and inexperienced youngsters. . . . We have had numerous reports of school children and young people using cigarettes made from this weed. . . . The National Congress of Parents and Teachers. . . is deeply concerned with increasing use of marihuana by children and youth."

Mexicans, in contrast, were seldom mentioned at the hearings and then only in passing. At several points, marihuana was described as a drug introduced into the United States by Mexicans." The violent behavior of Mexicans was described as the major issue only once and then in a letter from Floyd K. Baskette, city editor of the Alamosa (Colorado) Daily Courier. Baskette linked marihuana use to "hundreds" of violent crimes committed by Mexicans." Though often quoted as characteristic of perceptions of marihuana at the time, the letter is important precisely because it was so unrepresentative. Indeed, what had turned marihuana use from a Southwest problem to a "national menace" was the perception not only of geographical expansion but also of spread of use to a new group—youth. The Marihuana Tax Act was passed not to punish Mexican users but to save youthful ones.

Although Mexicans were not the main object of concern, they still figured in the discussion of marihuana in other ways. They were identified as the original users of the drug and at times were implicated in its dissemination.

The Mexican laborers have brought seeds of this plant into Montana and it is fast becoming a terrible menace. . . . We have numerous reports of school children and young people using cigarettes made from this weed."

Properly speaking, moreover, marihuana was seen not as a "youthful drug" (as in the 1960s) but as a "drug infecting youth." It was seen not as indigenous to youthful culture and experience but as an alien intrusion. Youth were regarded not as the willful instigators of use but as innocent, ignorant victims seduced and destroyed by the drug and its wily peddlers.

School children are the prey of peddlers who infest school neighborhoods. . . .High-school boys and girls buy the destructive weed without knowledge of its capacity for harm, and conscienceless dealers sell it with impunity. . . .The fatal marihuana cigarette must be recognized as a deadly drug and American children must be protected against it."

That youth has been selected by the peddlers of this poison as an especially fertile field makes it a problem of serious concern to every man and woman in America."

In general, youthful marihuana users were seen as innocent victims who became violent fiends only after use.

In contrast, the images of infection and seduction of the innocent were rarely used in regard to Mexican laborers or other low-status users. Marihuana instead was seen as indigenous and appropriate to them. If anything, low-status users were seen as the carriers of infection and as the seducers.

Despite the emphasis on youthful marihuana users, therefore, perceptions of Mexican users still exerted a significant indirect influence on perceptions of the marihuana menace. Although concern focused on youthful use, the drug itself was seen as essentially belonging to low-status groups, and it accordingly was perceived as dangerous and criminogenic, alien and infecting.

FBN Hegemony

There was a wide consensus about marihuana in the late 1930s among those few who discussed the drug: It was dangerous; it caused violent crime; it threatened the nation's youth. This consensus did not reflect a simple convergence of several independent assessments of the available evidence. Instead, it was largely created by the FBN, which effectively dominated public discussion of marihuana. The periodical articles of the period drew explicitly or implicitly on the bureau's own information and the sources that it favored, while ignoring what the bureau ignored. This happened precisely because there was no "national menace" and hence few persons knew about the drug. In such circumstances, the bureau was one of the only sources of information.

The clearest manifestation of the bureau's hegemony is that all of the articles sound the same. They make the same claims in virtually the same language. Marihuana, we are told again and again, was a problem only in the Southwest until "three or four" years ago, when it became a "national menace." It is the same as hashish, the Oriental drug of assassins. It is "more dangerous than cocaine or heroin." It is spread by evil peddlers to thrill-seeking youth and so on. One cannot read through the literature of the period without a recurring feeling of deja vu.

When we examine this uniformity closely, we can identify specific lines of influence. We have already seen that the New Orleans articles by Stanley, Fossier, and Gomila figured heavily in the FBN's arguments against marihuana. The Gomila and Stanley articles found their way into the Marihuana Tax Act hearings, and Anslinger incorporated a prisoner study and the various Old World myths recounted by Stanley into his own writing and testimony.°'

The periodical articles of the period were also influenced heavily by the New Orleans information, either directly or indirectly through the bureau. Several repeated almost verbatim the Old World marihuana legends, while others cited the Stanley prisoner study. A twofold crime theory presented by Gomila—that marihuana both caused unpremeditated violence and was used by criminals to fortify themselves for premeditated crimes—also was mentioned."

New Orleans, moreover, was the home of Robert P. Walton, a professor at the Tulane University School of Medicine, whose Marihuana: America's New Drug Problem was the decade's most comprehensive work on marihuana. Walton acknowledged learning about marihuana in New Orleans and reprinted the Gomila article as a definitive statement of the current state of the marihuana problem in the United States. His analysis followed the New Orleans-FBN assumptions by stressing menace, crime, and youthful use. Walton, in turn, directly influenced at least two articles, which reviewed his work and endorsed his conclusions."

The direct influence of the FBN is just as clear. Besides the one article actually coauthored by Anslinger, seven articles explicitly credited the bureau or its commissioner as a source of information. The bureau's examples of marihuana crimes, moreover, were repeated incessantly—the Texas hitchhiker who murdered a motorist, the West Virginia man who raped a nine-year-old girl, the Florida youth who murdered his family with an ax, the Ohio juvenile gang that committed thirty-eight armed robberies, the Michigan man who killed a state trooper, and other equally bloodcurdling tales. The frequent repetition of the same criminal cases, most of which first appeared in Anslinger's 1937 article, is one of the clearest pieces of evidence that the articles drew upon a common source. Finally, the bureau's idiosyncratic insistence on informing the public that Mexican marihuana was indeed the same as Oriental hashish was mirrored in several additional articles."

In sum, sixteen of the twenty-two articles in the Readers' Guide sample from 1935 to 1940 bear the mark of the FBN or its favored sources in one or more of the ways described above. The six that do not, moreover, serve to underline the bureau's importance in shaping marihuana beliefs. One of the articles was not about marihuana use in the United States at all but instead reported on hashish smuggling in Egypt. Another three discussed marihuana use in America but deviated from the established consensus in some way: Two drew on the work of Walter Bromberg of New York's Bellevue Hospital and described marihuana as fairly innocuous; a third characterized marihuana as dangerous but found claims of youthful use "unfounded.'" In short, the exceptions merely prove the rule. The pervasive belief that marihuana use in America was dangerous, violent, and a threat to youth was decisively shaped by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. The articles not influenced by the bureau either do not discuss American use or stand outside the dominant consensus about that use.

The FBN's hegemony also can be demonstrated by noting the evidence that generally was not cited. Just as periodical articles generally used the information propagated by the bureau, they virtually ignored the information that the bureau ignored. Studies by the Indian Hemp Commission in 1894, the U.S. Canal Zone Committee in 1926 and 1933, and Walter Bromberg in 1934, all of which distinctly downplayed the dangers of marihuana use, were rarely mentioned during the period. Walton alluded to the first two in his marihuana volume but did not take them seriously. Only two articles made use of Bromberg's findings. This may seem odd, since the three studies not only were available and obviously known but also constituted the most systematic work done on marihuana use to that time. The bureau, however, found their findings uncongenial to its own position and was able to drown them with silence. It never mentioned either the Indian or the Canal Zone study, and Anslinger made only one questionable reference to Bromberg in response to the questions of the House Committee on Ways and Means. Asked if Bromberg validated the marihuanacrime link, Anslinger argued that Bromberg hedged his conclusions and that his study, based as it was on a prison population, was unreliable. Both arguments were misleading. Anslinger himself accepted a secondhand report of the New Orleans study, which also was based on a limited sample of prisoners. Bromberg did not hedge his conclusions: He explicitly argued that the contribution of marihuana use to crime was greatly exaggerated."

The most important consequence of the bureau's domination over marihuana beliefs was that no one really opposed its efforts to procure a federal antimarihuana law. At the House hearings on the Marihuana Tax Act, for example, the opposition that surfaced was largely technical. Manufacturers of rope, hempseed, and hemp oil were concerned that their industries would be hampered by the law and were mollified by some minor changes in the text." William Woodward, the American Medical Association representative, seemed to object to the act on the wider grounds that marihuana use was not really a problem and that a federal law would unduly restrict future research on marihuana. These issues, however, were not the central concern of the AMA. Woodward used most of his testimony to object to the additional tax and registration burdens that a separate marihuana law would place on physicians. In his letter to the Senate hearings, moreover, these burdens were the only objections that he raised to the act. The narrow, technical nature of the AMA's objection to the act becomes even clearer when we realize that Woodward advocated including marihuana in the already existing Harrison Act. Such a move would have restricted research as much as a separate marihuana act and would have been just as irrational if marihuana use were not a real problem. Clearly, neither of these points was basic to the AMA's objection. Physicians did not oppose a federal law against marihuana; they merely wanted it in a form that would place the least financial and administrative burden on them» The bureau's dominance of the marihuana issue was complete.

NOTES

1. Edward W. Scripture, "Consciousness Under the Influence of Cannabis," Science, 27 October 1893, pp. 233-234; E. B. Mawer, "Hachisch Eating," Cornhill Magazine, May 1894, pp. 500-505; "Reports on Opium and Hemp," Spectator, 27 April 1895, pp. 570-571; Alfred H. Lewis, "Marihuana," Cosmopolitan, October 1913, pp. 645-655; Carlton Simon, "From Opium to Hash Eesh: Startling Facts Regarding the Narcotics Evil and Its Many Ramifications Throughout the World," Scientific American, November 1921, pp. 14-15; "Our Home Hasheesh Crop," Literary Digest, 3 April 1926, pp. 64-65; Scudamore Jarvis, "Hashish Smugglers of Egypt," Asia, June 1930, pp. 440-444. Both Spectator and Cornhill Magazine are British publications, but their presence in the Readers' Guide suggests that they were available to the reading public in the United States.

2. Richard J. Bonnie and Charles Whitebread II, The Marihuana Conviction (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1974), pp. 35-36; David F. Musto, The American Disease (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), p. 330.

3. Lewis, "Marihuana," p. 648.

4. Bonnie and Whitebread, Marihuana Conviction, pp. 32-38; Patricia A. Morgan, "The Political Uses of Moral Reform" (Ph.D. diss., University of California at Santa Barbara, 1978), pp. 82-83. The Agriculture Department, charged with enforcing the domestic provisions of the Food and Drug Act, commissioned its 1917 investigation to determine what effect the Treasury Department's 1915 ban on importation of cannabis for nonmedical use (under the import-export provisions of the same act) had had on domestic use. The Canal Zone report was made by a special committee established to study marihuana use in the Canal Zone. The committee took a wider view of the issue and gathered information on use elsewhere as well.

5. A. E. Fossier, "The Marihuana Menace," New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal 84 (1931):247-252; Frank Gomila and Madeline Lambou, "Present Status of the Marihuana Vice in the United States," c. 1931, reprint in Marihuana, ed. Robert P. Walton (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1938), pp. 27-39; Eugene Stanley, "Marihuana as a Developer of Criminals," Journal of Police Science 2 (1931):256. The Gomila article originally appeared sometime in the early 1930s and was reprinted later by Walton.

6. The New Orleans articles also warned that marihuana use was spreading from these groups to school children, thus conveying an image of infection that would become important in marihuana consensus of the 1930s.

7. Oriental legends are recounted also by Stanley and Fossier and figure heavily in the bureau's case against marihuana in the 1930s and later. These legends by themselves, however, cannot account for the dominant image of marihuana as a violence-producing drug, since they provide "evidence" for a number of stereotypes about the drug. The predominance of the violence stereotype was the unique contribution of New Orleans and the Southwest.

8. U.S., National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement, Crime and the Foreign Born (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1931), pp. 154, 205.

9. Ibid., p. 205.

10. Bonnie and Whitebread, Marihuana Conviction, pp. 70-77, 312.

11. Cited in Musto, American Disease, p. 222.

12. U.S., Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs, 1929 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office), p. 15. The annual reports of the bureau are identified by the year they cover, not the year they were published.

13. Ibid., 1936, pp. 59-60.

14. Bonnie and Whitebread, Marihuana Conviction, pp. 56-59.

15. Bureau of Narcotics, Traffic, 1929, p. 15.

16. Ibid., 1931, p.51.

17. Bonnie and Whitebread, Marihuana Conviction, p. 63.

18. Musto, American Disease, p.213.

19. Alfred Lindesmith, The Addict and the Law (New York: Random House, 1965); Musto, American Disease.

20. Bonnie and Whitebread, Marihuana Conviction, pp. 60-61; U.S., House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, Taxation of Marihuana, 75th Cong., ist sess., 1937, pp. 7-8.

21. Donald T. Dickson, "Bureaucracy and Morality," Social Problems 16 (1968):143-156.

22. This and the following paragraphs draw upon Bonnie and White-bread, Marihuana Conviction, pp. 56-126; and Morgan, "Moral Reform."

23. Bureau of Narcotics, Traffic, 1935, p. v.

24. Ibid., 1936, p. 57.

25. "Marihuana Menaces Youth," Scientific American, March 1936, pp. 150-151; Harry J. Anslinger and Courtney R. Cooper, "Marihuana: Assassin of Youth," American Magazine, July 1937, pp. 18-19, 150-153; Wayne Gard, "Youth Gone Loco," The Christian Century, 29 June 1938, pp. 812-813; Henry G. Leach, "One More Peril for Youth," Forum and Century, January 1939, pp. 1-2.

26. House of Representatives, Taxation of Marihuana, p. 6.

27. Ibid., p. 19.

28. "Marihuana Menaces Youth," Scientific American; "Marihuana More Dangerous Than Heroin or Cocaine," Scientific American, May 1938, p. 293; "New Federal Tax Hits Dealings in Potent Weed," Newsweek, 14 August 1937, pp. 22-23.

29. "Facts and Fancies About Marihuana," Literary Digest, 24 October 1936, pp. '7-8.

30. Earl A. Rowell and Robert Rowell, On the Trail of Marihuana: The Weed of Madness (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1939), p. 83.

31. Bureau of Narcotics, Traffic, 1936, pp. 59-60.

32. House of Representatives, Taxation of Marihuana, p. 24. At the shorter Senate hearings, Anslinger added that the marihuana user was much younger than the opium user. U.S., Senate, Finance Committee, Taxation of Marihuana, 75th Cong., ist sess., 1937, pp. 14-15.

33. House of Representatives, Taxation of Marihuana, pp. 18-45, 123- 124.

34. "Danger," Survey Graphic, April 1938, p. 221; Leach, "Peril for Youth."

35. George R. McCormack, "Marihuana," Hygeia, October 1937, pp. 898-899; "Marihuana More Dangerous Than Cocaine or Heroin," Scientific American, p. 293; "Marihuana," Journal of Home Economics, September 1938, pp. 477-479; "Marihuana Smoking Seen as Epidemic Among the Idle," Science News Letter, 26 November 1938, p. 340; Maud A. Marshall, "Marihuana," American Scholar, January 1939, pp. 95-101; Roger Adams, "Marihuana," Science, 9 August 1940, pp. 115-119.

36. Anslinger and Cooper, "Assassin of Youth," p. 150.

37. McCormack, "Marihuana," p. 899; Rowell and Rowell, Trail of Marihuana, p. 39.

38. "Marihuana More Dangerous Than Heroin or Cocaine," Scientific American, p. 293; Rowell and Rowell, Trail of Marihuana, p. 41.

39. Anslinger and Cooper, "Assassin of Youth," p. 150.

40. Bureau of Narcotics, Traffic, 1933, p. 36; 1937, p. 54; 1938, pp. 51-52.

41. House of Representatives, Taxation of Marihuana, pp. 6, 35, 45.

42. Ibid., pp. 18, 45, 123.

43. Ibid., p. 32. The Baskette letter and a 1935 letter to the New York Times from C. M. Goethe of Sacramento are the two pieces of evidence cited by Musto (American Disease, pp. 220, 223) to support his contention that anti-Mexican sentiment was behind the Marihuana Tax Act.

44. House of Representatives, Taxation of Marihuana, p. 45. See also Albert Parry, "The Menace of Marihuana," The American Mercury, December 1935, pp. 487-490; William Wolf, "Uncle Sam Fights a New Drug Menace . . . Marijuana," Popular Science Monthly, May 1936, pp. 14-15; Anslinger and Cooper, "Assassin of Youth"; McCormack, "Marihuana"; Gard, "Youth Gone Loco"; "Marihuana," Journal of Home Economics.

45. House of Representatives, Taxation of Marihuana, p. 6.

46. Anslinger and Cooper, "Assassin of Youth," p. 18. For other references to youth as innocent victims, see McCormack, "Marihuana"; "Danger," Survey Graphic; Clair A. Brown, "Marihuana," Nature, May 1938, pp. 271-272; Marshall, "Marihuana"; Adams, "Marihuana."

47. House of Representatives, Taxation of Marihuana, pp. 18-31; Anslinger and Cooper, "Assassin of Youth."

48. Parry, "Menace of Marihuana"; "Marihuana Menaces Youth," Scientific American; Wolf, "Uncle Sam Fights a New Drug Menace"; Anslinger and Cooper, "Assassin of Youth"; Clarence W. Beck, "Marijuana Menace," Literary Digest, 1 January 1938, p. 26; Gard, "Youth Gone Loco"; Marshall, "Marihuana."

49. Walton, Marihuana; "Marihuana Smoking Seen as Epidemic," Science News Letter; "The History of Marihuana," Newsweek, 28 November 1938, p. 29.

50. Articles directly crediting the bureau or Anslinger: McCormack, "Marihuana"; "Marihuana More Dangerous Than Heroin or Cocaine," Scientific American; Brown, "Marihuana"; Gard, "Youth Gone Loco"; "Marihuana," Journal of Home Economics; Leach, "One More Peril for Youth"; S. R. Winters, "Marihuana," Hygeia, October 1940, pp. 885- 887. Among the articles repeating examples of crimes are Parry, "Menace of Marihuana"; Beck, "Marihuana Menace"; "Danger," Survey Graphic; "Marihuana Smoking Seen as Epidemic Among the Idle," Science News Letter; Marshall, "Marihuana."

51. C. S. Jarvis, "Hashish Smuggling in Egypt," The Living Age, January 1938, pp. 442-447; "Facts and Fancies About Marihuana," Literary Digest; "Marihuana Gives Some a Jag," Science News Letter, 14 January 1939, p. 30; "Potent Weed," Newsweek.

52. House of Representatives, Taxation of Marihuana, p. 24; Walter

The Rise of the Killer Weed 75

Bromberg, "Marihuana Intoxication," American Journal of Psychiatry 91 (1934):303-330 (see especially pp. 307-309).

53. House of Representatives, Taxation of Marihuana, pp. 59-64, 67-86.

54. Ibid., pp. 87-121; Senate, Taxation of Marihuana, pp. 33-34. Bonnie and Whitebread (Marihuana Conviction, pp. 164-169) and almost everyone else have erroneously painted Woodward as a patron of science and a major opponent of the bureau's hysterical view of marihuana. A closer reading of his House testimony and his Senate letter clearly shows that he was no such thing.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|