7 FROM KILLER WEED TO DROP-OUT DRUG

| Books - The Strange Career of Marihuana |

Drug Abuse

7 FROM KILLER WEED TO DROP-OUT DRUG

Among those who persisted in seeing marihuana as a dangerous drug, the characterization of that danger changed dramatically in the mid-1960s. What had once been regarded as a "killer weed" became seen as a "drop-out drug." This change can get lost easily amid the loud debates over the legality and morality of marihuana use, but it is nonetheless significant. It involved a shift not only in the specific dangers claimed for marihuana use but also, and more importantly, in the general image of the drug and its users. It entailed nothing less than a transformation of the assumptions framing the public discussion of marihuana.

We have traced the emergence of the image of marihuana as a drug that made its users violent, criminal, and aggressive. Perhaps the clearest statement of this pre-1960s "killer weed" image was made by antidrug crusaders Earle and Robert Rowell in 1939: "While opium Kills ambition and Deadens initiative, marihuana incites to immorality and crime."

In the turbulent debate over marihuana beginning in the 1960s, this image was widely replaced by the opposite assertion that marihuana induced passivity and destroyed motivation. What the Rowells had once said about opium in contrast to marihuana now was said about marihuana itself: It killed ambition and deadened initiative; it created an amotivational syndrome; it was a "drop-out drug."

Thus, in summarizing the drug's effects, Time argued in 1965 that marihuana "affects user's judgment and if used daily will dull a student's initiative"; and Benjamin Spock, the pediatrician and political activist, noted in 1971 that "a small percentage of users, the 'potheads', make its frequent use the focus of their existence and lose some of their ambition and aim."2

We shall document the rise of the "drop-out drug" image and explain its emergence in terms of three social conditions: the declining influence of narcotics officials on public discussion, the proliferation of marihuana use among middle-class youth, and the new role of marihuana as a symbol of the Counterculture. These three conditions correspond respectively to the three guiding concepts presented in chapter 1: entrepreneurship, social locus, and symbolic politics. The symbolic meaning of marihuana was especially important in shaping the image of the drug, and we shall accordingly dwell upon it.

A discussion of the "drop-out drug" image inevitably leads to a consideration of what we have called the "Hippie Hypothesis." This argues that in the late 1960s, marihuana became a symbol of intergenerational conflict and thus of hedonism, radicalism, permissiveness, rejection of authority, and other features of the period's youthful Counterculture. Objections to the drug became based on what it represented, not on its effects. Opposing marihuana use and supporting antimarihuana laws became a symbolic way of condemning the Counterculture and asserting the validity of the dominant culture.

The "Hippie Hypothesis" is partly right. It is undoubtedly correct to see marihuana as a symbol in the wider cultural and political conflict of the day, but it is misleading to argue that marihuana was rejected for what it represented, not because of its effects. To draw so sharp a distinction between the drug's meaning and its perceived effects does not do justice to the complexity of the public discussion of marihuana at the time. The two were inextricably mixed together, for what the drug symbolized helped to shape the effects imputed to it. We can understand the dynamics of symbolism at work here by examining the "drop-out drug" image and its causal roots.

RISE OF THE DROP-OUT DRUG

The once common belief that marihuana made the user aggressive and violent virtually disappeared in the late 1960s. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics and its various organizational successors did attempt to purvey the violence image, but few accepted it. During the 1966 Senate Judiciary Committee hearings on the Narcotic Rehabilitation Act, FBN Commissioner Henry Giordano, who had succeeded Harry Anslinger in 1962, offered the following time-honored assessment of the dangers of marihuana use:

From my studies and experience, one theme emerges—that marihuana is capable of inducing acts of violence, even murder. The drug frees the unconscious tendencies of the individual user, the result being reflected in frequent quarrels, fights, and assaults.'

To support this contention, Giordano offered the standard FBN data—examples of marihuana-induced individual violence in the United States and collective violence in non-Western countries.

Giordano repeated his claim at the 1968 House hearings on control of LSD, but this was the last time that any major witness mentioned the connection between marihuana and violence.' Testimony at Senate hearings on juvenile delinquency and drug use in the same year and on narcotic addiction and drug abuse in 1969 linked marihuana use to automobile accidents, acute psychotic reactions, and the amotivational syndrome but not to violence.' The violence claim was absent also from the series of hearings in 1969 and 1970 on the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act and was ignored even by the 1974 hearings on the "marihuana-hashish epidemic," which made a concerted effort to publicize every possible marihuana-related danger. The National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse concluded that "marihuana does not cause violent or aggressive behavor."6

The bureau's view of marihuana, in short, no longer dominated public discussion as it once had. Quite the contrary; narcotics officials now seemed to be pushed along in a wider flow. By 1971, John Ingersoll, head of the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, had largely given up the violence claim and was describing marihuana as "psychologically habituating, often resulting in an amotivational syndrome."7

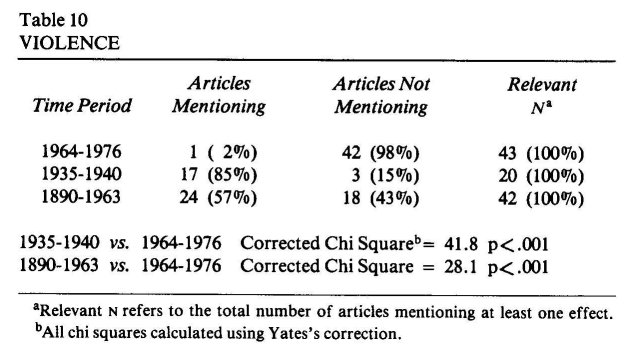

The violence claim disappeared from the media as well. In the Readers' Guide sample from the 1964-1976 period, only one (2 percent) of the forty-three articles that discussed the effects of marihuana mentioned violence, compared to 57 percent in the pre-1964 period and

85 percent in the late 1930s (see Table 10). At the same time, numerous articles explicitly denied that marihuana made the user violent.

The Stepping-stone Hypothesis, which formed the basis of the case against marihuana in the 1950s, fared only somewhat better. To be sure, progression to "harder" drugs was mentioned as a danger of marihuana use by 16 percent of the articles, and the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse heard testimony in 1971 that lax enforcement of marihuana laws inevitably would engender a heroin epidemic in the near future.' This claim, however, was losing popularity too. The Stepping-stone Hypothesis was denied more often than it was affirmed and was rarely the focus of attention.

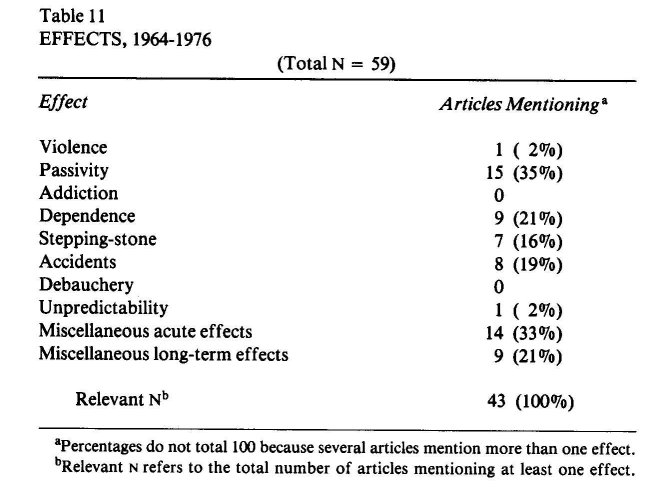

As the violence and stepping-stone claims declined in importance, other alleged dangers of marihuana became prominent. Marihuana intoxication was said to cause "acute psychotic reactions" (roughly equivalent to the "temporary insanity" of the pre-1964 period but without any hint of violence) and to impair driving ability by interfering with psychomotor functioning. The time-honored belief that chronic marihuana use caused wholesale mental and physical deterioration was recast with the help of a wealth of new research into a number of more specific claims. Witnesses at Senator East-land's 1974 hearings on the "marihuana-hashish epidemic" argued that chronic use caused brain damage, lung disease, fetal deaths and abnormalities, chromosome damage, lowered testosterone levels, and impaired immune response.9 Finally, it was routinely asserted that although marihuana definitely was not physically addicting, it did lead to a psychological habituation (or emotional dependence) in which the user became totally involved in drug use (see Table 11).

The danger most commonly attributed to marihuana in the 1964- 1976 period, however, was the "amotivational syndrome." Longterm marihuana use was said to destroy ambition and initiative, to interfere with the effort to cope with the world, and to facilitate withdrawal from reality. It led, in the words of the commission, to "lethargy, instability, social deterioration, a loss of interest in virtually all activities other than drug use."

Like the violence claim of an earlier day, the amotivational syndrome claim implied that marihuana use destroyed the user's self-control and released the basically antisocial human nature previously held in check. The difference lay in how this underlying human nature was pictured. According to the violence claim, marihuana released a fundamentally destructive, aggressive human nature and thus caused a failure of restraint. According to the amotivational syndrome claim, marihuana uncovered an essentially passive, ambitionless human nature and thus produced a failure of achievement. In short, the central characterization of the adverse effects of marihuana use shifted in the mid-1960s from a failure of restraint to a failure of achievement.

It is tempting to see in the shift from violence to amotivational syndrome a change from a "public safety" perspective to a "public health" perspective. This is accurate to an extent. According to the violence claim, users were primarily threats to others and hence constituted a law enforcement problem. In contrast, according to the amotivational syndrome, they were primarily threats to themselves and hence represented a health problem. The public safety/ public health distinction, however, also implies a shift in characterization of the user from sinner to victim that did not occur. Whether considered a violent criminal or a drop-out, the marihuana user was viewed ambivalently as partially culpable for his condition and partially a victim of the wiles of the drug.

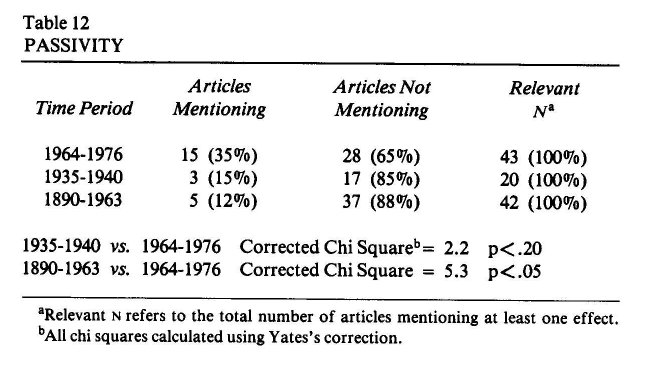

The amotivational syndrome appeared in 35 percent of the periodical articles from 1964 to 1976, substantially more than the 12 percent figure for the pre-1964 period and the 15 percent figure for the late 1930s. Although found in less than a majority of articles, it was still the most cited adverse effect of marihuana. No one claim dominated the periodical discussion of marihuana in the 1964- 1976 period as violence had in the 1930s, because no one organization monopolized the social definition of reality as the Federal Bureau of Narcotics had in that previous era (see Table 12)."

Despite the plurality of authorities and opinions, however, the amotivational syndrome did dominate judicial deliberations, congressional hearings, and federal reports on marihuana. In his landmark 1967 decision upholding the constitutionality of Massachusetts's marihuana law, Judge G. Joseph Tauro described marihuana use as follows:

Many succumb to the drug as a handy means of withdrawing from the inevitable stresses and legitimate demands of society. The evasion of problems and escape from reality seem to be among the desired effects of the use of marijuana. '2

The charge of passivity and withdrawal was first voiced in congressional hearings in 1968 by Dr. Donald Louria of the New York State Council on Drug Addiction:

Drug-induced withdrawal is a problem of increasing severity in our society, and LSD is only one vehicle for this. Even marihuana in heavy doses can, after repeated use, produce the same loss of ambition, rejection of previously established goals, and retreat into a solipsistic, drug-oriented cocoon."

In the 1969-1970 hearings on drug control reorganization, the amotivational syndrome was the major claim made against marihuana; it was mentioned in eight of the eleven pieces of testimony that discussed adverse effects." It was, moreover, the only danger that was stressed or discussed at length. For example, Roger Egeberg, assistant secretary for health and scientific affairs in HEW, made the following point:

Marihuana use particularly because it starts at such an early age is apt to make many people go off into a pleasant euphoria or other means of evading reality at a time, 15, 16, 17, 18 years when they should be setting their aims. . . . This I would say is the tragedy to all of society with respect to the use of marihuana [emphasis added]."

Dana Fornsworth of the Harvard University Health Services also focused on the amotivational syndrome.

But I am very much concerned about what has come to be called the "amotivational syndrome" [emphasis added]. I am certain as I can be. . . that when an individual becomes dependent upon marihuana. . . he becomes preoccupied with it. His attitude changes toward endorsement of values which he had not before; he tends to become very easily satisfied with what is immediately present, in such a way that he seems to have been robbed of his ability to make appropriate choices.'

The 1972 report of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse took the amotivational syndrome more seriously than any other potential adverse effect of marihuana. It denied that marihuana use led to acute psychotic reactions except in "rare cases" or among a "predisposed few" and doubted that "significant physical, biochemical, or mental abnormalities could be attributed solely to . . . marihuana smoking." It concluded that the "weight of evidence is that marihuana does not cause violent or aggressive behavior" and that "recent research has not yet proven that marihuana use significantly impairs driving ability or performance." It also found no evidence of addiction, progression to harder drugs, or chromosome damage and birth defects. In contrast, the report was careful to stress that the amotivational syndrome was the real danger for heavy users and might become a major problem in the United States as use increased.''

More importantly, the commission was sensitive to the fact that Americans were particularly worried about the amotivational syndrome. In discussing "why society feels threatened," the report noted that parents were concerned that "marihuana will undermine or interfere with academic and vocational career development and achievement" or even worse, that it will lead to "amotivation" and "dropping out."" The commission itself denied that marihuana as then used was an important causal factor in either "dropping down" or "dropping out," but the very fact that it took time to do so indicates the social importance of these claims.

Senator Eastland's 1974 hearings pictured the amotivational syndrome as the most significant behavioral effect of marihuana use.

The most notable and consistent clinical changes that have been reported in heavy marihuana smokers include apathy approaching indolence, lack of motivation . . . reduced interest in socializing, and attraction to intense sensory stimuli.

Possibly the issue of greatest importance in the area of behavioral toxicity of marihuana is the question of the amotivational syndrome."

The amotivational syndrome was mentioned by twelve of the fourteen witnesses who testified on the behavioral effects of marihuana—several times as often as any other adverse effect—and it was the only behavioral effect to be systematically discussed.2°

Beyond its mere quantitative predominance, the amotivational syndrome also provided a basis for understanding the other adverse effects of marihuana and for constructing an image of the user as a person. It thus played the same pivotal cognitive role that violence did in the 1930s. Psychological dependence, the second most frequently mentioned adverse effect in the late 1960s and early 1970s, was basically a synonym for the amotivational syndrome: Both claims implied that the heavy marihuana user became totally wrapped up in drug use and lost interest in everything else. The lowered testosterone levels in males and brain damage caused by marihuana use were partly interpreted as the direct causes of the amotivational syndrome. The latter was said to limit the user's cognitive ability to deal with the world and the former to lead to a general reduction in drive.2' The putative link between marihuana use and automobile accidents was understood to result from the user's reduced desire and ability to cope with the world.

Those who sought to typify users implicitly described them as embodiments of the amotivational syndrome. Passivity, lack of motivation, withdrawal from reality, and an inability to cope were seen not as some of the user's many traits, but as master traits that defined his very being. In Judge Tauro's adjectival overkill, marihuana users were "the disaffiliated, the neurotic and psychotic, the confused, the anxious, the alienated, the inadequate, the weak.' 22 For University of California, Berkeley, medical physicist Hardin Jones, the amotivational syndrome was nothing less than a whole lifestyle of "dropping out, indolence, lowering of goals, alienation," and " kookiness." 23

In short, the amotivational syndrome was not simply one important effect imputed to marihuana. It formed the core of the dominant image of both drug and user. Marihuana did not simply cause an amotivatonal syndrome among other things; it was in essence a "drop-out drug."

MARIHUANA AND THE COUNTERCULTURE

The rise of the "drop-out drug" image can be seen as the result of the demise of the dominance of narcotics officials over public discussion, the increase in middle-class marihuana use, and most importantly, the emergence of marihuana as a symbol of the Counterculture.

In the early 1960s, President Kennedy initiated a series of White House conferences, panels, and commissions on "narcotics and drug abuse" that effectively opened up the discussion of marihuana to other government agencies and interested groups." Later in the decade, the rapid increase in marihuana use made the drug a major social issue for the first time. It became the subject of widespread popular debate, headlines, and endless hearings and reports. The basis of the dominance of the marihuana issue by narcotics officials was thus undermined Marihuana became an important matter; other interested groups (notably scientists, physicians, and public health officials) became involved; users themselves became a force in their own right; and the general populace was aroused. What once had been a small-scale, uninterrupted monologue became a wide-ranging, raucous cacophony of voices, and narcotics officials could not hope to dominate a public discussion of such scale and diversity. The main proponent of the "killer weed" image thus lost ground, while the diversity of voices created the opportunity for a new image of marihuana to emerge.

The emergence of this new image was brought about partly by the rise of youthful middle-class marihuana users. In the 1920s and 1930s, when Mexican laborers and other lower-strata groups had been perceived as the primary users of marihuana, the drug had been seen as creating the kind of deviant behavior regarded as typical of those groups—aggression or a failure of restraint. As marihuana use among middle-class youth increased rapidly in the 1960s, the image of the drug shifted accordingly. If violence was the kind of deviance expected from lower-strata groups, then a failure to achieve, a loss of motivation and initiative, appeared to be the typical way that middle-class kids went bad and the ultimate failure of middle-class socialization. They were expected not to commit violent crimes or go insane in any spectacular way but rather to drop out or squander their potential. The dangers attributed to marihuana changed from the deviance expected from the older using group to that expected from the newer group. The "killer weed" became a "drop-out drug."

Above all, the image of marihuana changed because the drug became a symbol in the wider struggle between the dominant society and the Counterculture. As used here, "Counterculture" refers to the political and cultural rebellion of middle-class youth during the late 1960s and early 1970s, as well as to those who participated in this rebellion in its widest sense—not only those who became involved in radical politics or experimented with alternative lifestyles but also the much larger number who shared the sense of alienation and the value commitments that fostered these activities.

"Symbol" has two quite different meanings. In one sense, a symbol is something that refers conceptually to something else. Thus rain is a symbol for precipitation of a certain kind, horse a symbol for a particular species of four-legged animal, and Counterculture a symbol of the youthful rebellion of the late 1960s, early 1970s. In each case, the word is a conceptual designation of the object. In a second sense, a symbol is something that not only refers to but also embodies something else and thus is responded to as if it were that other thing. It evokes in us the same experience as the object it symbolizes. This usage is nicely described by Gertrude Jaeger and Philip Selznick:

The symbol itself takes on the human significance possessed by its referent. To the naturalist, the flock of birds may be a sign of land, and nothing more. To the sailor long at sea, the flock of birds may acquire symbolic status and he may respond to them much as he will later respond to his actual homecoming. Black may be merely a denotative sign of death, death merely a natural sign of disease. But when black is a true symbol of death, we respond to it much as we would humanly respond in the presence of death."

We are concerned here about marihuana as a symbol in this second sense. For many persons in the late 1960s and early 1970s, marihuana not only was associated with the Counterculture but also came to embody it: They responded to the one as if it were the other.

The symbolic status of marihuana was sometimes directly acknowledged in public discussion, and an effort was occasionally made to distinguish the drug's effects from its meaning. As a 1971 National Review article put it, "That appears to me to be the nub of the pot problem: The weed is an adjunct, forcing tool and instrument of initiation for a lifestyle that generally rejects or seeks to bring down 'ordered life as we know it.' "26 The following year in the same journal, Jeffrey Hart was even more explicit, arguing that the evils of marihuana lay in its meaning, not its effects ("I care not a fig for its physical effects"): Marihuana symbolized the Counterculture, and the main purpose of antimarihuana laws was "to lean on, to penalize the Counterculture."27

For their part, proponents of penalty reduction often took pains to argue that marihuana should not be regarded as anything more than a drug. The national commission explicitly "tried to desymbolize" marihuana so as to build support for decriminalization."

Public discussion of marihuana, however, rarely drew such a neat distinction between meaning and effects, and the most significant consequence of the transformation of marihuana into a symbol lay in the way the effects themselves were reconceptualized. The relationship of marihuana to the Counterculture was not in itself a major issue in the discussion of the drug's dangers or in the debate over penalty reduction. Contrary to the Hippie Hypothesis, the objection to marihuana and to marihuana law reform was based primarily on the harmful physical and psychological effects of the drug as policymakers and the media perceived them, not on the lifestyle associated with it. Opposition to the drug was conceptualized in terms of what it did, not in terms of the culture it symbolized or was tied to. The relationship between marihuana and the Counterculture was rarely raised in congressional hearings or periodical articles. When it was mentioned, it was usually a matter of fact, not as a major reason to oppose the drug.

In short, the symbolic status of marihuana did not render its effects as a drug unimportant in public discussion; rather it shaped how these effects were discussed. Here lies the truly important consequence of the transformation of marihuana into a symbol. When the harmful effects of the drug upon the individual were discussed, they were described in a way determined by the fact that marihuana was the symbolic embodiment of the Counterculture. The social characteristics of the Counterculture, as perceived by the dominant society, were projected onto marihuana and then said to be psychological effects inherent in the drug. Because the Counterculture was characterized as passive and escapist, marihuana became seen as a producer of passivity and escape on the individual level. The amotivational syndrome, in other words, was simply the Counterculture writ small and turned into a psychiatric diagnosis.

Once established, this new image of marihuana persisted because it was functional: It reinforced a way of explaining the Counterculture that was simultaneously a way of explaining it away, of accounting for it without having to come to terms with it. The easiest way to condemn youthful rebellion was to describe it in purely negative terms—as dropping out from organized social life, as escaping from reality, as failure. In this way, the adult generation and the dominant society did not have to acknowledge and deal with what youth were doing, but only with what youth were not doing. They did not have to confront the youthful rebels' philosophical, moral, and political commitments or the alternative world that they were trying to build in however halting, half-hearted, and incomplete a way.

The image of marihuana as a source of an amotivational syndrome facilitated this purely negative view of the Counterculture, because if the amotivational syndrome was simply the Counterculture writ small, the Counterculture could be seen simply as the amotivational syndrome writ large. The amotivational syndrome provided a seemingly simple, delimited model on the psychological level for understanding a more complex, diffuse, and thus harderto-grasp phenomenon on the cultural level.

Contemplated in itself, the Counterculture might have been too complex to support a simple image of it as a mere negation or dropping out. Viewed as a giant version of the amotivational syndrome, it was easier to understand and dismiss. The assessment of the amotivational syndrome was unassailable. It was unambiguously negative—loss of motivation, escape from reality, passivity. As a syndrome, moreover, it was a psychiatric condition with clear overtones of pathology. As the amotivational syndrome writ large, the Counterculture too appeared as unquestionably negative, and its negativity appeared as something specific and palpable—a mass psychiatric syndrome. The discrediting view of the Counterculture thus was reinforced by its association with marihuana, conceived as the source of the amotivational syndrome.

To restate this in a sentence: Marihuana functioned effectively as a cultural symbol. To use Clifford Geertz's terminology, it provided a template for organizing and making sense of a multitude of impressions of the Counterculture. It served as a "sensuous embodiment of what is abstract and ineffable" in Jaeger's and Selznick's phrase.29

The public images of drug and culture thus were mutually reinforcing. Because it symbolized a cultural phenomenon that was widely seen as a mere passive withdrawal from reality, marihuana use ceased to be seen primarily as a creator of violent criminals or as a stepping-stone to heroin and became instead a source of the amotivational syndrome. Because the Counterculture was symbolized by a "drop-out drug," its reputation as a pathological denial of society was made palpable and thus reinforced. Symbol and referent, marihuana and Counterculture, became confounded in public discussion.

NOTES

1. Earl Rowell and Robert Rowell, On the Trail of Marihuana: The Weed of Madness (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press, 1939), P. 83.

2. "Pot Problem," Time, 12 March 1965, p. 49; Benjamin Spock, "Preventing Drug Abuse in Children," Redbook, May 1971, p. 36.

3. U.S., Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Narcotic Rehabilitation Act of 1966, 89th Cong., 2d sess., 1966, p. 459.

4. U.S., House of Representatives, Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, Subcommittee on Public Health and Welfare, Increased Control Over Hallucinogens and Other Dangerous Drugs, 90th Cong., 2d sess., 1968, pp. 101-103.

5. U.S., Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Juvenile Delinquency, 90th Cong., 2d sess., 1968, pp. 4561, 4687; U.S., Senate, Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, Subcommittee on Alcoholism and Narcotics, Narcotics Addiction and Drug Abuse, 91st Cong., ist sess., 1969, pp. 31-40, 95-100, 136, 197.

6. U.S., National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding (1972), p. 73.

7. "More Controversy About Pot," Time, 31 May 1971, p. 65.

8. Ibid.

9. U.S., Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws, Marihuana-Hashish Epidemic and Its Impact on United States Security, 94th Cong., ist sess., 1975.

10. National Commission, Marihuana, pp. 86-87.

11. The level of significance for the 1935-1940 vs. 1964-1976 comparison was greater than .05. The difference, however, was in the predicted direction. More importantly, references to passivity prior to the mid-1960s were perfunctory, and the effect was rarely said to be the distinguishing or central feature of the drug.

12. "Commonwealth vs. Leis and Weiss," in Marihuana, ed. Stanley Grupp (Columbus, Ohio: Charles E. Merrill, 1971), p. 295.

13. House of Representatives, Hallucinogens, p. 158.

14. The passages included here are the following: U.S., Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency, Narcotic Legislation, 91st Cong., ist sess., 1969, pp. 501, 516, 530-537, 571-609; U.S., Senate, Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, Special Committee on Alcoholism and Narcotics, Federal Drug Abuse and Drug Dependence Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Act of 1970, 91st Cong., 2d sess., 1970, p. 143; U.S., House of Representatives, Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, Subcommittee on Public Health and Welfare, Drug Abuse Control Amendments-1970, 91st Cong., 2d sess., 1970, pp. 180-181, 188, 551-554; U.S., House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, Controlled Dangerous Substances, Narcotics, and Drug Control Laws, 91st Cong., 2d sess., 1970, pp. 280ff., 331-334, 449. They include testimony from public health officials, the House Select Committee on Crime, the National Congress of Parents and Teachers, the 1969 Presidential Task Force on Narcotics, Marihuana, and Dangerous Drugs, the National Association of Retail Druggists, and others.

15. House of Representatives, Controlled Dangerous Substances, p. 280.

16. House of Representatives, Drug Abuse Control Amendments, p. 554.

17. National Commission, Marihuana, pp. 59, 61, 73, 79, 84-89.

18. Ibid., pp. 97, 99.

19. Senate, Marihuana-Hashish Epidemic, pp. 51, 193. The hearings included much testimony on the physiological and biochemical effects of marihuana as well.

20. Ibid., pp. 18-30, 154-169, 206-250.

21. Ibid., pp. 154-169, 206-250.

22. U.S., House of Representatives, Select Committee on Crime, Crime in America—Drug Abuse and Criminal Justice, 91st Cong., 1st sess., 1969, p. 172.

23. Senate, Marihuana-Hashish Epidemic, pp. 214, 232.

24. U.S., President's Ad Hoc Panel on Drug Abuse, Progress Report (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962); White House Conference on Narcotic and Drug Abuse, Proceedings (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962); U.S., President's Advisory Commission on Narcotic and Drug Abuse, Final Report (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1963).

25. Gertrude Jaeger and Philip Selznick, "A Normative Theory of Culture," American Sociological Review 29 (1964):653-669.

26. S. K. Oberdeck, "Problems of Pot," National Review, 1 June 1971, p. 597.

27. Jeffrey Hart, "Marijuana and the Counter Culture," National Review, 8 December 1972, p. 1348.

28. National Commission, Marihuana, p. 167.

29. Clifford Geertz, "Ideology as a Cultural System," in The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973), pp. 193-233; Jaeger and Selznick, "Normative Theory of Culture."

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|