METHODOLOGICAL APPENDIX

| Books - The Strange Career of Marihuana |

Drug Abuse

METHODOLOGICAL APPENDIX

The present study has two important methodological features. First, it is comparative. It does not merely describe the historical development of marihuana law and ideology; it systematically compares what was said about marihuana at various times. This allows us to determine what was truly distinctive about marihuana ideology at any given point. Second, the study includes a quantitative content analysis of periodical articles to show that the historical picture of marihuana ideology it presents is indeed representative of what was said about marihuana at various times. This analysis allows us to document, for example, that violence was the effect most often imputed to marihuana in the 1930s not only with selected quotes (the representativeness of which much be accepted as given) but also with the statistical datum that x percent of articles from the 1930s mentioned violence compared to only y percent in the 1960s. The result is a much more systematic, rigorous account of marihuana ideology than otherwise possible.

Data used in this study comes from periodical articles indexed in the Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature (RG) and from a variety of other primary sources. The Readers' Guide materials have two uses: First, the relative frequency of articles on marihuana in the RG provides a measure of the magnitude of the marihuana issue over the years. Second, a content analysis of these articles gives us a representative picture of what was said about the drug. We shall call these the "magnitude study" and the "content study" respectively. Data from other primary sources are used to reinforce, refine, or modify the conclusions reached from the RG data.

READERS' GUIDE DATA

The Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature is the major index of articles appearing in general-interest periodicals in the United States. A successor to such nineteenth-century publications as Poole's Index to Periodical Literature, it has been published by the H. W. Wilson Company since 1900 with the assistance of the American Library Association (ALA). There is even a retrospective volume for the 1890s. Bound volumes of the RG initially appeared every five years, but the intervals have gradually decreased to one year. The RG has consistently sought to index major periodicals of a broad, general, and popular nature. The list of articles is selected by a vote of subscribers, supervised by the ALA Committee on Wilson Indexes, and revised at intervals to add new titles and drop others. In effect, then, the RG indexes those periodicals judged by major librarians to be the most useful and important. Despite the continual addition and deletion of titles, the RG is generally judged to have maintained a fairly constant scope throughout its existence.

Within this general consistency, there have been a number of changes in emphasis and content. Among other things, the number of periodicals indexed has increased continually from 66 in volume 1 (1900-1904) to 118 in volume 12 (1939-1941), 132 in volume 23 (1961-1963), and about 160 in recent volumes. This means that the total number of articles indexed has risen. The 1900-1904 volume contains 574 pages per year; the 1925- 1928 volume, 702 pages; the 1937-1939 volume, 1,020 pages; the 1945- 1947 volume, 1,138 pages; and the 1955-1957 volume, 1,385 pages. In subsequent years, the annual number of pages has remained fairly constant, the 1974-1975 volume containing 1,232 pages per year. Furthermore, the RG initially indexed books, government publications, and the annual reports of intellectual associations in addition to periodical articles. Books were discontinued after volume 3 (1910-1914), and the reports and government publications gradually dwindled. Subsequent to a 1952 ALA-sponsored policy change, scholarly publications (for example, The American Journal of Sociology) were transferred from the RG to the International Index, which was begun in 1913 as a supplement to the RG and currently appears in two volumes as the Social Science Index and the Humanities Index. An effort was made to reserve the RG for publications of more general interest; therefore, periodicals for specialists or for specific hobbies were explicitly excluded.'

In short, the major changes in the content of the RG since 1900 have been an increase in the number of periodicals covered, a gradual decrease in nonperiodical material, and the exclusion of scholarly and highly specialized periodicals. The first of these changes occasionally must be kept in mind in analyzing the data from the magnitude study. For example, since the RG contained about 20 percent more articles in the early 1970s than in the late 1930s (1,232 pages vs. 1,020 pages), a mere 20 percent increase in the annual frequency of marihuana articles in the later period over the earlier period would not indicate that more attention was being given to marihuana relative to other issues.

The other changes do not seem to affect our findings in any way. Non-periodical material never constituted more than a small fraction of the entries in the RG, and the exclusion of scholarly publications in 1952 does not appear to have caused any abrupt change in the frequency or content of articles on marihuana.

The Magnitude Study

Variations in the frequencies of articles on marihuana and alcohol that are indexed in the Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature from 1890 to 1976 are used as indicators of the relative amount of attention given marihuana during various time periods. Assessments of the relative importance of the marihuana issue are based on comparisons of the frequency of articles on marihuana at a particular time with both the frequency of articles on alcohol at the same time period and the frequencies of articles on marihuana at other periods.

This methodology need not assume that the frequency of articles in the RG at any one time is an accurate indicator of the magnitude of the marihuana issue at the same time. Rather, since the analysis is comparative, it must make the somewhat less exacting assumption that the relationship between the article frequency in the RG and the magnitude of the issue in broader public discussion remains constant over time.

A count was made of articles in the RG on alcohol and marihuana. Included among the alcohol articles were all those indexed in the following categories: alcohol, alcoholics, alcoholism, alcohol and youth, alcohol and servicemen, alcohol education, liquor laws, liquor problem, liquor traffic, Prohibition, and temperance. Marihuana articles included those indexed under the marihuana, cannabis, hashish, and THC headings.

In choosing the alcohol categories, an effort was made to include all and only those articles that appeared to discuss the substance either as a social problem or as a matter of scientific interest. Articles under those headings concerning alcohol as a beverage or the alcoholic beverage industry were excluded, because a brief survey of titles showed them to be oriented to the alcohol consumer (that is, how to mix better drinks) or investor (that is, how to invest wisely in the industry), not to a discussion of alcohol as a social problem or matter of scientific interest.

The annual frequencies of articles on alcohol and marihuana were computed for each time period covered by a volume of the RG. The following ratios were then calculated to allow for comparison:

1. marihuana/alcohol ratio: the ratio of the annual frequency of articles on marihuana to the annual frequency of articles on alcohol for each time period.

2. marihuana/1967-76 mean: the ratio of the annual frequency of articles on marihuana for each time period prior to 1967 to the average annual frequency of articles on marihuana from 1967 to 1976 (31.4).

The use of these ratios is straightforward, given the assumptions we have made. The larger the marihuana/alcohol ratio for any time period, the greater the amount of attention given marihuana relative to alcohol at the time. The larger the marihuana/1967-76 mean ratio, the closer the amount of attention given marihuana in a pre-1967 time period comes to approximating the amount of attention given the drug in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a period in which marihuana was irrefutably an important issue. Both ratios thus provide a measure of the relative importance of marihuana as a public issue at any given time.

The Content Study

Periodical articles on marihuana are studied to determine what beliefs about the drug have been presented in the printed media. Periodical, rather than newspaper, articles are used for two reasons. First, periodical articles are more accessible, since a wide range of periodicals are indexed in the RG. In contrast, hardly any newspapers besides the New York Times are indexed for more than a decade or two. Second, newspaper accounts of marihuana use usually report specific arrests or seizures rather than generally discussing the drug. They are thus not suited for our inquiry.

The sample of articles was taken from the marihuana, THC, hashish, and cannabis categories in the Readers' Guide from 1890 to 1976. Articles indexed under "hemp," mostly from the early 1900s, were ignored because they invariably concerned the production of hemp for rope, hempseed, and hemp oil and thus did not discuss the psychoactive uses of the plant.

The initial sample consisted of all articles in the four categories from 1890 to 1966 (N = 56) and a random selection of one-fifth of the articles from 1967 to 1976 (N ..= 65). The latter group actually turned out to be slightly more than 20 percent of the 314 articles indexed during the decade. The limited selection of articles after 1966 was necessary because the frequency of articles on marihuana increased sharply at the time, as noted in chapter 3.

The articles were read to determine whether or not they expressed or reported opinions on the following items:

1. Degree of Danger: How dangerous is marihuana?

2. Possibility of Moderate Use: Is moderate (that is, limited, safe) use possible?

3. Effects: What kinds of harm does marihuana use cause to users and those around them?

4. Users: From which social groups is the typical marihuana user drawn?

Items one through three are central to any characterization of marihuana. "Degree of danger" is probably the most important explicit issue in any public discussion of drug use. The belief that a drug can be used in moderate doses without ill effect, whatever the danger of heavier use, has been crucial in the differential perception of narcotic and nonnarcotic drugs. Central to the American condemnation of "narcotics" has been the argument that their use invariably leads to abuse, while the contemporary defense of alcohol is that despite the clear danger of protracted use, moderate use clearly can be distinguished from abuse. Finally, the specific effects imputed to marihuana have changed strikingly over time and thus constitute an important variable in the drug's image. Item four helps to indicate how public perceptions of who uses marihuana have developed. All four items are relevant to our assessment of the hypotheses presented in chapter 2 and to our examination of marihuana ideology.

Fourteen of the articles in the periodical sample provided no data on any of the four items and were excluded from further study. Eleven were reports from Science on efforts to isolate the active constituents of marihuana or on observations of the effects of marihuana on nonhuman animals. The three others included a history of marihuana with no references to the twentieth century, a 1969 report of Mexican efforts to crack down on marihuana cultivation, and a defense of the Consumer Union's 1972 drug report. A fifteenth article was removed because it turned out to be a series of letters to the editor that expressed a variety of viewpoints and hence could not be easily coded. The deletions reduced the actual sample N to 106-47 from the 1890-1963 period and 59 from the 1964-1976 period.'

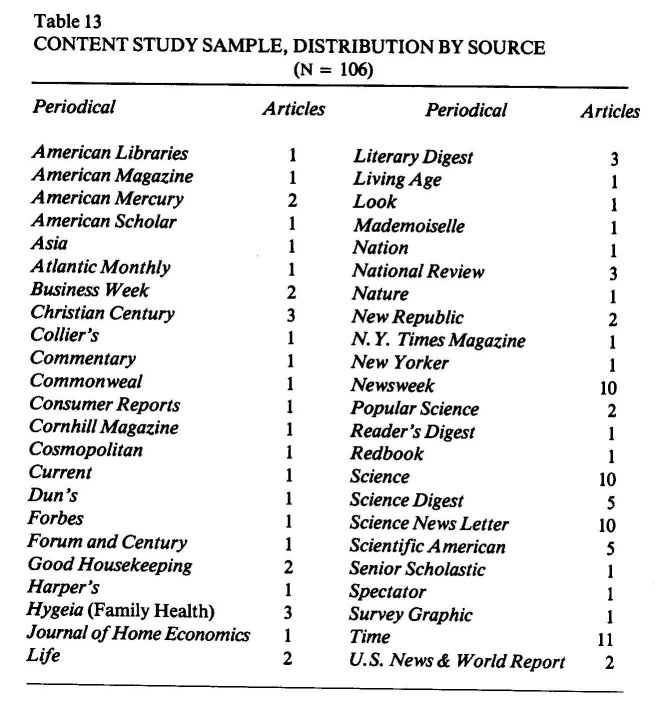

As Table 13 shows, the articles appeared in a wide range of publications and included a disproportionate number from popular and professional science journals. The most represented publications were Time (eleven), Science (ten), Newsweek (ten), Science News Letter (ten), Scientific American (five), and Science Digest (five). The particular publication or kind of publication in which an article appeared generally had little effect on how marihuana was characterized in regard to the items relevant here.

Articles were read and coded for the opinions they expressed on each of the four items. The coding criteria were these:

1. Degree of Danger. An article was said to describe marihuana as "dangerous" if it explicitly referred to use as a "menace," "peril," or "problem" or if it paid preponderant attention to at least some of the negative effects of the drug. An article was classified as describing marihuana as "not so dangerous" if it explicitly denied that use was a problem, de-emphasized or questioned reported dangers, or paid preponderant attention to the harmlessness or the positive uses of the drug. In all, fifty-three articles were classified as "dangerous," thirty-five as "not so dangerous," and the remaining eighteen as expressing no opinion.

2. Possibility of Moderate Use. An article was said to assert that moderate use was "impossible" if it explicitly said that using marihuana even once or twice was dangerous or if it described any condition that would make limited, safe use impossible. These conditions included addiction, which implies that the user is likely to lose control over use; subtlety of danger, which implies that negative effects occur without the user realizing them; immediacy of danger, which implies that negative effects (violence, acute psychotic reaction) can occur after even one use; and unpredictability of effect, which implies that users have no way of predicting effects and thus limiting their use accordingly. In contrast, an article was said to describe moderate use as "possible" if it explicitly stated that marihuana could be used one or more times without ill effect, if it distinguished "experimental," "social," or "weekend" use from heavier use, or if it compared marihuana favorably to drugs like alcohol, the moderate use of which is generally deemed possible. Twenty-five articles were classified as "impossible," thirty-nine as "possible," and forty-two as expressing no opinion.

3. Effects. An article was coded for each effect that it reported that marihuana had on the user and/or on others. Effects were categorized as follows:

violence—violent crimes against self or others (homicide, rape, robbery, suicide) or the predisposition to commit such acts.

passivity—loss of ability or desire to participate in the world; heightened desire to escape or withdraw.

addiction—physical dependence (tolerance and/or withdrawal symptoms). dependence—psychological or emotional habituation without physical dependence.

stepping-stone—progression to more dangerous drugs.

debauchery—socially disapproved erotic activity.

accidents—impaired psychomotor abilities leading to motor vehicle accidents. unpredictability—no consistent pattern of effects.

miscellaneous acute effects—unspecified or numerous immediate effects. miscellaneous chronic effects—general long-term debilitation.

In all, eighty-five articles mentioned at least one effect of marihuana use.

4. Users. Fifty-nine of the articles referred to social groups believed to be the predominant users of marihuana. Articles were coded for each group mentioned according to the following categories: (1) Mexicans and other Spanish-speaking groups; (2) blacks; (3) bohemians and aesthetes; (4) hippies and rebels; (5) other marginal groups (East Indians, Orientals, criminals, the "idle and dissolute"); (6) youth in general (teenagers, adolescents, high-school students); (7) youth of the upper and middle strata (college students, middle-class youth, prep school students, children of professionals, politicians, and businessmen); (8) adults of the upper and middle strata (suburbanites, businessmen, professionals); (9) musicians and writers. The first five categories, which consist of groups that historically have been socially marginal in some sense, were also combined into a larger, "marginal" caregory; groups six through eight were combined into a larger, "respectable" category. In this way, groups likely to be perceived as inherently immoral were distinguished from those that would not. "Musicians and writers," rarely mentioned in any case, were left out as ambiguous.

Articles that reported the belief of a person other than the author were coded as though they had expressed the belief directly if they did not offer substantial criticism or cite contrary evidence. Thus a 1970 Time report of John Kaplan's argument that marihuana was relatively innocuous was coded as describing marihuana as "not so dangerous" since it cited his position at length and mentioned criticisms only as amending, not refuting, his case. Similarly, a 1974 Newsweek report of Robert Kolodny's finding that marihuana use reduced testosterone levels in men was coded as describing marihuana as "dangerous" since it offered no contrary arguments and described the study as a "jolt to pot smokers."'

Tabulations were made for each item for the 1890-1963 and 1964-1976 periods as well as for the 1935-1940 subperiod. 1964 was taken as a convenient cutting point, since the first drugs-on-campus, drugs-in-the-suburbs articles appeared in that year, heralding the rise of middle-class marihuana use. The 1935-1940 subperiod, which included the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act, was singled out, because it represented the height of concern over marihuana in the pre-1964 period. The tabulations allow for a general characterization of each period and for comparisons between periods. Such comparisons were made between 1964-1976 and both 1890- 1963 and 1935-1940, using Chi square modified by Yates's correction for continuity as a test of significance. This statistical analysis gives us a clear sense of the distinctiveness of marihuana beliefs in each time period.

Articles categorized as expressing no opinion on a particular item were excluded from the statistical analyses of that item. Percentage calculations were based on the number of cases expressing a clear opinion (the Relevant N referred to in the various tables in the text), not on the total number of cases. This may seem a questionable move since it removes from eighteen to forty-seven cases, depending on the item. It makes sense, however, when we realize that the high number of "no opinions" reflects nothing more than the narrow focus of many of the articles. Some articles report on marihuana use among a particular group without discussing effects. Others discuss effects without mentioning specific users. Still others discuss the magnitude of danger without specifying either effects or users. Depending on the focus of the article, some matters are relevant, others are not. The high rate of missing data reflects nothing more profound than this simple fact. Given this problem, one could have simply restricted the sample to general, all-inclusive articles on marihuana, but that would have excluded the vast majority of articles in the sample and removed many valuable bits of data. Instead it was decided to include for each item only those articles from the sample that addressed the item with the recognition that the Relevant N thus created differed somewhat from item to item.

DATA FROM OTHER PRIMARY SOURCES

A variety of other primary sources are cited in this study to augment the findings of the RG studies. The most important of these are various federal government documents.

Congressional hearings and federal reports on psychoactive drug use are used to study marihuana ideology as it directly influenced and was used to justify changes in the law. A list of major hearings and reports was compiled from the major histories of American drug controls and from several anthologies.' The reports include material from the 1931 Wickersham Commission volume, entitled Report on Crime and the Foreign Born, the 1956 interdepartmental committee on narcotics, a series of inquiries into "narcotics and drug abuse" commissioned by President Kennedy in the early 1960s, President Johnson's 1966 crime commission, the 1972 marihuana report of the National Commission of Marihuana and Drug Abuse, and the annual assessments of marihuana and health by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Included among the hearings are the 1937 House and Senate hearings on the Marihuana Tax Act, the various hearings on the 1951 Boggs Act and the Narcotics Control Act of 1956, the 1950 Kefauver organized crime hearings, various mid-1960s hearings on LSD and marihuana, the numerous hearings on the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, the Eastland subcommittee's 1974 hearings on the so-called marihuana-hashish epidemic, and the 1975 hearings on marihuana decriminalization.

The annual reports of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (Traffic in Opium and Other Dangerous Drugs) from 1926 to 1962 were examined to facilitate our understanding of the vicissitudes of the bureau's stance toward marihuana and its role in shaping marihuana ideology and law. This time period was chosen to cover the heyday of the bureau's control over federal drug policy—from the bureau's creation in 1930 to the retirement of Commissioner Harry Anslinger in 1962. With the election of John F. Kennedy and his establishment of a White House conference and a presidential commission to study narcotics and drug abuse, drug policy became a wider government concern and ceased to be the relatively private domain of any one federal agency.' The marihuana ideology of federal narcotics officials after 1962 was studied along with those of other policymakers through testimony at congressional hearings as well as through official pamphlets and speeches.

NOTES

1. The discussion of the Readers' Guide is drawn from Esther J. Bone, "The Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature: A Study" (MLS thesis, Kent State University, 1965); Frances W. Cheney, Fundamental Reference Sources (Chicago: American Library Association, 1971); and Paul Vesenyi, An Introduction to Periodical Bibliography (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Pierean Press, 1974).

2. The 106 articles in the sample are listed in the bibliography with an RG after the entry.

3. "If Pot Were Legal," Time, 20 July 1970, p. 41; "Pot and Sexuality," Newsweek, 29 April 1974, p.57.

4. Richard J. Bonnie and Charles Whitebread II, The Marihuana Conviction (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1974); David F. Musto, The American Disease (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973); Rufus King, The Drug Hangup (Springfield, Ill.: Charles Thomas, 1974); Erich Goode, ed., Marihuana (New York: Atherton Press, 1970); Stanley E. Grupp, ed., Marihuana (Columbus, Ohio: Charles E. Merrill, 1971); and K. Austin Kerr, The Politics of Moral Behavior (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1973). A full list of the hearings and reports studied is included in the bibliography.

5. King, Drug Hang-up.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|