3 MARIHUANA BEFORE THE SIXTIES - AN OVERVIEW

| Books - The Strange Career of Marihuana |

Drug Abuse

3 MARIHUANA BEFORE THE SIXTIES - AN OVERVIEW

The marihuana issue prior to the mid-1960s was very different from the marihuana issue of today. Not only were the images of the drug and its users strikingly dissimilar but also the amount of attention given to the drug in those days was considerably less. Let us survey the pre-1960s period by examining these two issues, beginning with the attention given to the drug.

MAGNITUDE OF THE ISSUE

Marihuana use has been a major public issue in the United States since the mid-1960s. It has attracted front-page headlines, innumerable surveys of use and attitudes, a national commission report, and voluminous hearings. Few Americans would fail to recognize its name. This notoriety inevitably influences our efforts to understand the drug's prior history. We too easily assume that because marihuana use recently has been a major issue it always has been so. When we turn to the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, for example, we may decide too readily that it must have riveted the attention of the media, the policymakers, and the populace.

Such, at least, has been the cursory conclusion of many who have studied marihuana in the 1930s. "By the late 1920s and early 1930s," Henry Brill reports, "there was widespread alarm about this new drug problem." Marihuana use is said to have generated "mass hysteria," "front-page headlines," and "widespread journalistic interest and public anxiety."2 The Federal Bureau of Narcotics's efforts to produce national antimarihuana legislation is pictured as an "all-out attack," and its antimarihuana campaign is said to have reached "a high pitch" by the time of the congressional marihuana hearings in 1937.' Concern about marihuana use by Mexicans in the Southwest in the 1930s is described as having been "intense," and a "marihuana ideology" is pictured as having been an important part of anti-Mexican sentiment` Others who have studied the period make no explicit judgment on the magnitude of the issue, but their references to the bureau's "publicity campaign" seem to imply that marihuana did attract a great deal of attention.' The artificial grouping of newspaper articles, speeches, and hearings that inevitably occurs in any serious study of marihuana also conveys this impression.

In fact, however, the opposite was true. Prior to the 1960s, marihuana was a nonissue in the United States nationally and in most local areas. It hardly ever made headlines or became the subject of highly publicized hearings and reports. Few persons knew or cared about it, and marihuana laws were passed with minimal attention. To document these claims, let us take a more systematic look at the changing importance of the marihuana issue in the wider scope of public discussion. Our findings will help us to evaluate the Anslinger and the Mexican hypotheses.

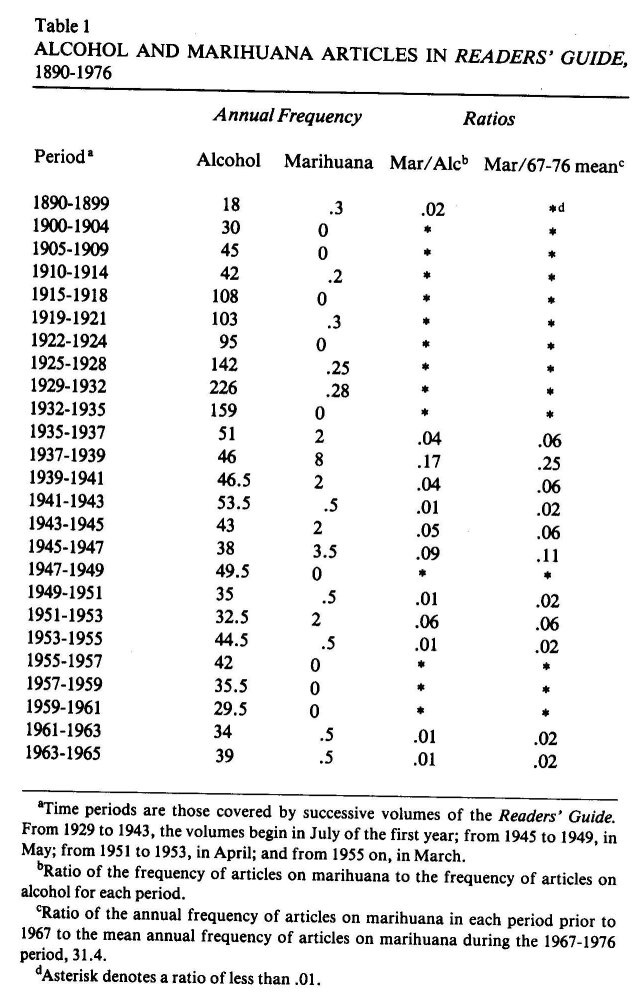

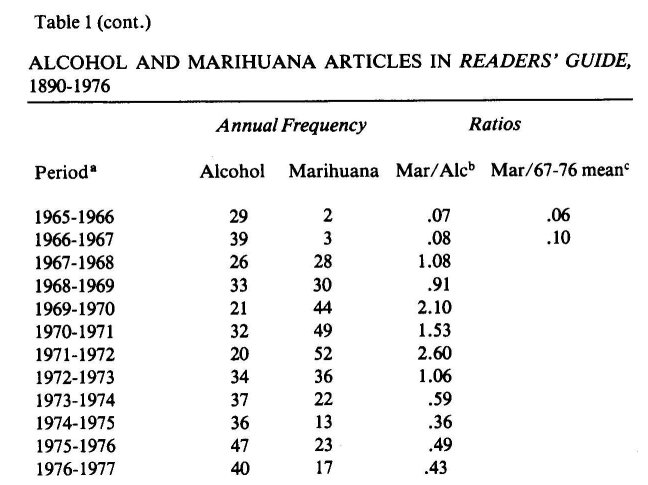

We can begin by taking the relative frequency of articles on marihuana in the Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature (to be cited as RG) as an indicator of the overall amount of attention given to the drug in public discussion. By comparing the frequency of articles on marihuana in a particular time period with the frequency of articles on alcohol in the same period and the frequency of articles on marihuana in other periods, we can ascertain how important the marihuana issue was during that period.6

Table 1 presents the relevant data. The time periods given are those covered by successive bound volumes of the Readers' Guide. The first two columns list the annual frequency of articles on alcohol and marihuana respectively in each period. The third column presents the ratio of marihuana articles to alcohol articles (the "marihuana/alcohol" ratio) in each period and the fourth column, the ratio of the annual frequency of marihuana articles in the time periods prior to 1967 to the average number of articles appearing yearly between 1967 and 1976, 31.4—the "marihuana/1967-1976 mean" ratio. The greater these ratios, the more important the marihuana issue was at any particular time prior to the mid-1960s.

As the table shows, the annual frequency of articles on alcohol in the RG increased dramatically from 30 in 1900-1904 to 108 in 1915-1918 and reached an apex of 226 in 1929-1932. With the repeal of Prohibition, it dwindled from 159 in 1932-1935 to roughly one-third that number, 51, in 1935-1937. In subsequent decades, the annual frequency varied erratically from 53.5 in 1941-1943 to 21 in 1969-1970 to 47 in 1975-1976 but never again approached the average for the Prohibition period-147 articles per year between 1919 and 1935.

Between 1890 and 1966, the RG indexed only fifty-five articles on marihuana, with twenty-four, or nearly half, appearing between 1935 and 1941, around the time of the Marihuana Tax Act. Even during that time, however, the annual frequency never went above eight. In the 1950s, despite a general concern with drug use and a rash of congressional hearings and special symposia, a mere six articles appeared in the RG. Only with the increase in use by middle-class youth in the late 1960s and the associated rise of the antiwar movement and the Counterculture did marihuana receive much attention. The annual frequency of marihuana articles indexed in the RG jumped from three in 1966 to twenty-eight in 1967 and reached a peak of fifty-two in 1971 (almost equal to the total number of marihuana articles appearing in the RG prior to 1967).

Before the mid-1960s, the marihuana/alcohol ratio exceeded .10 only once, during 1937-1939. Even then, right after the Marihuana Tax Act, marihuana articles appeared only 17 percent as often as articles on alcohol. In thirteen of the twenty-seven time periods prior to 1967, the marihuana/alcohol ratio failed to reach .01. In 1967 this changed dramatically. The marihuana/alcohol ratio jumped to 1.08; and for the ensuing five years, marihuana articles appeared in the RG as often as or more often than articles on alcohol, the ratio reaching a peak of 2.60 in 1971. The ratio subsequently declined to .43, but still remained 2.5 times greater than the highest pre-1967 ratio.

The marihuana/1967-1976 mean ratio tells a similar story. It was less than .01 for fourteen of the twenty-seven time periods prior to 1967. It exceeded .05 in only eight periods and reached a maximum of a mere .25 in 1937-1939. Marihuana articles appeared prior to 1967 at only a small fraction of the rate of the 1967-1976 period.

In short, the RG data clearly imply that marihuana was an insignificant issue prior to the mid-1960s, at least when compared to either alcohol at the same time or marihuana after the mid-1960s. A closer look at the historical record confirms this conclusion.

Prior to the efforts of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics to publicize the evils of marihuana in the mid-1930s, the drug was virtually ignored on the national level. It was overlooked by two seminal pieces of federal drug legislation, the 1914 Harrison Act and the 1922 Narcotic Drugs Import-Export Act, and was not mentioned in the major drug studies of the late 1910s and the 1920s.7 Although it was the subject of reports by the Department of Agriculture in 1917, a U.S. Canal Zone committee in 1925, and the surgeon general in 1929, none of these gained much attention or reflected widespread concern. Neither marihuana nor the Canal Zone report, for example, was mentioned anywhere in the annual reports of the Canal Zone's governor.'

On the local level, marihuana received just sporadic press attention. Only one episode in New Orleans in 1926 appears to have been of any significance. On October 17 of that year, the report of a major police attack on "vice and marihuana" made the front page of the New Orleans Times-Picayune as well as other local newspapers. Moreover, unlike newspapers elsewhere, the Times-Picayune did not feel compelled to define marihuana, thus clearly assuming its readers' knowledge of the substance.

Contrary to the Mexican Hypothesis, marihuana was not a major public issue in the Southwest in the 1920s or early 1930s. The numerous state antimarihuana laws in that region, for example, were usually passed in a perfunctory way with little attention or publicity. Floor debate was minimal and occasionally jocular; newspaper coverage was slight.9

Even in California, the drug appears to have been a nonissue during the 1920s and 1930s. Marihuana rarely was mentioned in anti-Mexican propaganda or in discussions of Mexicans and crime. It received little press coverage, and the few articles that appeared showed little familiarity with the drug. During the 1930s, for example, the San Francisco Chronicle printed about two articles per year on marihuana. Only one made the first page, and only two were feature articles in the magazine section. One of these, Bushnell Diamond's "Shocking New Menace to Nation's Youth" on January 24, 1937, described marihuana as a new drug, previously unknown to California: "Until last year, addiction seemed to be confined chiefly to New York, where it had been introduced by foreigners." The California Division of Narcotics Enforcement published its first marihuana pamphlet (Marihuana—Our Newest Narcotic Menace) only in 1939. It too stressed that marihuana use was unknown in California prior to the "last few

Despite the bureau's publicity efforts, the notoriety of marihuana barely increased in the mid-1930s. The claims of advancing menace and the heated rhetoric that marked the bureau's publications, periodical articles, and the congressional hearings on the Marihuana Tax Act at the time belied the minuscule amount of attention actually given to the drug. In the year prior to the hearings held by the House of Representatives on the tax act in April 1937, five major newspapers—the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Denver Post, and Dallas Morning News—published only one article apiece per month on marihuana, and only two of these sixty-one pieces made the front pages."

The actual passage and signing of the antimarihuana legislation was greeted with nonchalance: The New York Times's terse wire-service report on the signing outdid the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, and the New Orleans Times-Picayune, all of which ignored both the passage and the signing. The San Francisco Examiner paid somewhat more attention, giving the House vote seven paragraphs on page two and the signing a five-line dispatch on the front page.' 2 Neither the American Year Book, Americana Annual, nor Britannica Book of the Year, however, mentioned the Marihuana Tax Act in its summary of congressional activity for 1937. Compared to the growth of fascism abroad and conflicts over New Deal policies at home, marihuana simply was not newsworthy.' 3

In the decade or so following passage of the Marihuana Tax Act, the only major indication of concern over the drug came in 1939, when Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia appointed a special committee to investigate the marihuana problem in New York City. The LaGuardia Committee and its eventual report received little attention outside law enforcement and medical circles, however; and even in New York City, marihuana was not a major issue. The New York Times carried only a handful of articles per year on the drug, and most of these were perfunctory reports of arrests and seizures buried on the inside pages. It ignored the establishment of the LaGuardia Committee and relegated a summary of its 1945 report to the last page.' 4

The 1950s and early 1960s witnessed numerous congressional hearings, White House conferences, and special panels on drug use in general, but marihuana did not share the attention, as only two examples will prove. In April of 1951, the House Committee on Ways and Means held hearings on legislation to increase and consolidate the penalties for trafficking in illicit drugs—what became known as the Boggs Act. In 238 pages of testimony, there were only two discussions of marihuana, both of which occurred as brief digressions." Eleven years later, at President Kennedy's White House Conference on Narcotic and Drug Abuse, marihuana again was conspicuous by its absence from the deliberations. Although it was mentioned at several points, there were only two sustained discussions of it: a two-page description of marihuana smuggling from Mexico and a short exchange over the dangers of marihuana. A comment during the conference by Alfred Lindesmith, a sociologist, accurately described the amount of attention given the drug:

Nothing has been said about marihuana, and my impression of marihuana has been that it is generally agreed that it presents a relatively trivial problem from a number of points of view."

No one leapt to disagree.

Marihuana use thus was a very minor issue in the United States during the entire first six-and-a-half decades of the twentieth century. Between 1890 and 1966 periodical articles on marihuana appeared only a fraction as often as articles on alcohol during the same period or articles on marihuana in subsequent years. The drug was roundly ignored by newspapers and official hearings and reports. Even at the height of the marihuana "menace" in the late 1930s, the drug made hardly a ripple. The marihuana issue of the 1930s or 1950s was quantitatively far different from the marihuana issue of the late 1960s. The former was an obscure matter, the province of a few law enforcement officials and moralists; the latter was a major public issue.

This conclusion has implications for our discussion of both the Mexican and the Anslinger Hypotheses. Any effort to root the Marihuana Tax Act in political pressure arising from antimarihuana and anti-Mexican sentiment in the Southwest must take into account the fact that marihuana was not a major issue in that area in the 1920s and 1930s. There was no major surge of concern in the mid-1930s and little interest in the fate of the bureau's legislative efforts. The association of marihuana with Mexicans may have influenced discussion and policymaking on the national level in some way, but neither concern about marihuana in the Southwest nor pressure from that region on the bureau was very intense. Marihuana was not a prominent part of any anti-Mexican crusade nor central to any racial stereotype of Mexicans.

Any discussion of the successful entrepreneurship of the Bureau of Narcotics must also recognize the insignificance of the marihuana issue in the mid-1930s. The fact that marihuana was such a nonissue was a crucial factor in the success with which the relatively small, underfunded Narcotics Bureau shaped national marihuana policy. The less that people know or care about an issue, the more likely it is that a small organization can decisively shape the laws concerning that issue without trouble or resistance.

IMAGES OF DRUG AND USER

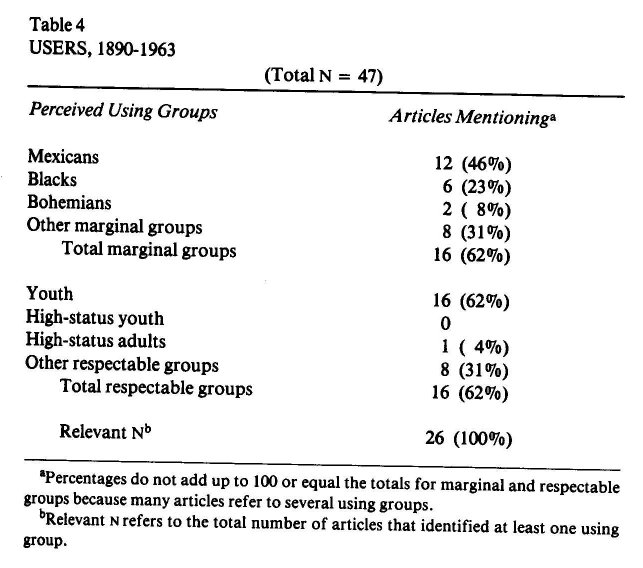

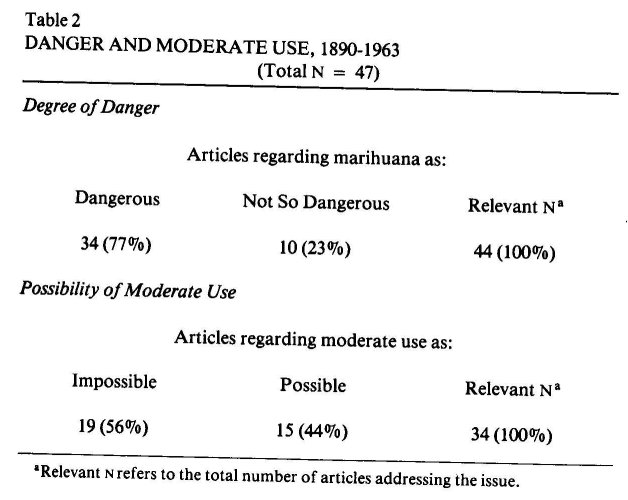

Although conceptions of marihuana and its users changed greatly between the late 1890s and the early 1960s, certain themes do mark the period as a whole. We can review these briefly by turning to our content analysis of the Readers' Guide articles for the period. Forty-seven articles were included in the sample for the 1890-1963 period. How they characterized marihuana and its users can be taken as representative of public discussion as a whole.

Marihuana was most commonly seen as dangerous and moderate use as impossible (see Table 2). Seventy-seven percent of the forty-four articles that addressed the issue regarded marihuana as dangerous, while 56 percent of the thirty-four articles that referred to moderate use deemed it impossible.

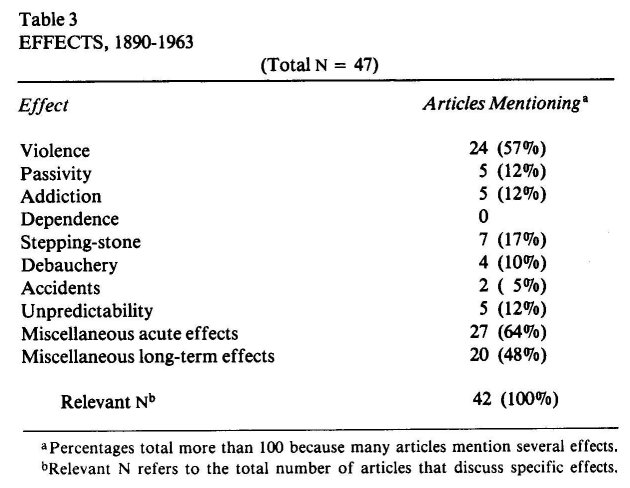

Marihuana was said to have a wide array of effects (see Table 3). Sixty-four percent of the forty-two articles that discussed specific effects mentioned a panoply of acute physical and psychological consequences—distortions of time and space perception, uncontrollable laughter, rapid movement of ideas, stimulation of the imagination, delusions of grandeur, hallucinations, loss of inhibitions, suggestibility, seizures, raving fits, irresistible impulses, and so forth. About 48 percent referred to the general effects of chronic use—"weakening of moral fiber," "disintegration of personality," "general instability, mental weakness, and finally insanity," and physical deterioration. Other effects such as addiction, passivity, stepping-stone, accidents, and debauchery were mentioned less often.

The one specific effect that received the most attention by itself, however, was violence, which was mentioned by 57 percent of the articles. It was virtually the only effect to receive protracted attention. It was often explicitly said to be the main or most important danger of marihuana use. Examples of marihuana-induced crimes were recited and ancient legends about marihuana and violence were recounted.

The marihuana user had two very different social identities (see Table 4). On the one hand, he was seen as a member of one of a number of marginal social groups; 46 percent of the twenty-six articles that spoke to this issue described him as Mexican or Spanish-speaking (often a laborer), while others described him as black, Oriental, East Indian, or white déclassé. On the other hand, the marihuana user was seen by 62 percent of the articles as a youth, a school child, or a high-school student of indeterminate social class and race. The reason for this ambiguity is simply that particularly in the 1935-1940 period, marihuana was perceived to be spreading from the former groups to the latter groups.

This is but a survey. The details of the development of marihuana law and ideology prior to the mid-1960s is the subject of the next two chapters.

NOTES

I. Henry Brill, "Recurrent Patterns in the History of Drug Dependence and Some Interpretations," in Drugs and Youth: Proceedings of the Rutgers Symposium on Drug Abuse, ed. J. R. Wittenborn et al. (Springfield, Ill.: Charles Thomas, 1968), p. 22.

2. Lester Grinspoon, Marihuana Reconsidered (New York: Bantam, 1971), p. 23; David Solomon, ed., The Marihuana Papers (New York: New American Library, 1966), pp. xv-xvi; Richard M. Blum and associates, Society and Drugs (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1969), p. 71.

3. David Smith, ed., The New Social Drug (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1970), p. 1; Roger Smith, "U.S. Marihuana Legislation and the Creation of a Social Problem," in New Social Drug, ed. D. Smith, p. 110.

4. David F. Musto, The American Disease (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), P. 219; John Helmer, Drugs and Minority Oppression (New York: Seabury Press, 1975), p. 75.

5. Alfred Lindesmith, The Addict and the Law (New York: Random House, 1965), p. 228; Edward M. Brecher et al., Licit and Illicit Drugs (Boston: Little, Brown, 1972), pp. 413-419.

6. See the Methodological Appendix for a more detailed discussion of the magnitude study.

7. Richard J. Bonnie and Charles Whitebread II, The Marihuana Conviction (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1974), pp. 49-56.

8. United States Canal Zone Governor, Annual Report of the Governor of the Panama Canal Zone (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1923-1930).

9. Richard J. Bonnie and Charles Whitebread II, "History of Marihuana Legislation," in Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding, ed. U.S. National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1972), Appendix I, pp. 491-498.

10. Patricia A. Morgan, "The Political Uses of Moral Reform" (Ph.D. diss., University of California at Santa Barbara, 1978); California Division of Narcotics Enforcement, Marihuana—Our Newest Narcotics Menace (Sacramento: California State Printing Office, 1939).

11. Donald T. Dickson, "Bureaucracy and Morality," Social Problems 16 (1968):143-156; John F. Gainer and Allyn Walker, "The Puzzle of the Social Origins of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937," Social Problems 24 (1977):367-376.

12. New York Times, 3 August 1937; San Francisco Examiner, 15 June 1937 and 3 August 1937.

13. In contrast, forty years later to the day, President Jimmy Carter's - advocacy of marihuana decriminalization made front page headlines. See, for example, San Francisco Chronicle, 3 August 1977.

14. New York Times, 12 January 1945.

15. U.S., House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, Control of Narcotics, Marihuana, and Barbiturates, 82d Cong., ist sess., 1951.

16. White House Conference on Narcotic and Drug Abuse, Proceedings (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962), p. 165.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|