Chapter Six: THE DRUG TAKERS 1920-1970

| Books - The Social Control of Drugs |

Drug Abuse

Chapter Six: THE DRUG TAKERS 1920-1970

Having now reached the point where the broad history of control has been catalogued, the next stage is to interpret this within a sociological framework. The basic questions are, firstly, why did the system change and, secondly, what produced the impetus for change. These questions lead us to consider the types of persons who were classified as the drug takers. This issue will be the subject of this chapter. Later we can consider the role of the medical profession and then examine a number of secondary factors which were instrumental in the changes although they may not have been of primary importance.

First the type of people who were classified as the drug takers. For information about this group of people we must examine two major areas; Home Office figures and the crime statistics.

Most of the evidence about the drug takers in Britain comes from the Home Office figures. They have had an enormous influence on policy decisions; almost every Parliamentary debate on drug taking has used them to support or refute an argument, whilst a number of research workers have tried to show how they underestimate the 'true' extent of drug taking. Although they may be viewed as defective, they are still seen as "the best that is available" and still used as a sort of moral barometer.

There are a number of separate issues here. One issue centres around the arguments put forward by the labelling theorists who see deviant behaviour as simply behaviour that people so label. They would argue that until recently it would have been usual to discuss the extent of addiction in Britain by quoting and analysing the official reports — in this case the Home Office register of known addicts and the crime statistics. It would also have been usual to note that these figures ought to be treated with caution, as all such statistics contain many defects for research purposes. They are, after all, prepared by officials as book keeping records, and provide meagre information about characteristics of either the offenders or the offences which they describe. As far as the means of obtaining the information is concerned, it is well known that different kinds of behaviour in different kinds of social situations have different probabilities of becoming officially known to those agencies. However, in spite of these numerous defects, the reader was asked to 'make do' with these figures.

In the last few years the limitations of this approach have become increasingly recognised, although there is still some reluctance to abandon it entirely. As Austin Turk has remarked, "It is genuinely puzzling that scientists have been so persistent in trying to carry on research using second-hand and for their purposes virtually useless data collected by non-scientists for non-scientific purposes, and they have for so long, in Sellin's words 'permitted non-scientists to define the basic terms of their enquiry'."1 Kitsuse and Cicourel have also criticized the use of official statistics, arguing that they are rates of deviant behaviour which are produced by the actions taken by persons in the social system, which define, classify and record certain behaviour as deviant. If a given form of behaviour is not interpreted as deviant by such persons it would not appear as a unit in whatever set of rates we might attempt to explain, e.g., in crimes known to the police or Court records, etc.2

Central to Kitsuse's and Cicourel's argument is the distinction they make between what they call the social conduct which produces a unit of behaviour, and the organizational activity which produces a unit in the rate of behaviour. The former they call the behaviour producing process, the latter the rate produc-ing processes. So for example we may be concerned with issues about a person's drug taking (the behaviour producing process) but it would require a separate research problem to account for that person's drug taking being recorded on the Home Office figures. Or, as Turk says, "the individuals found in any category of official statistics have in other words been so classified after passing through a series of interactions with a number of people where eventually someone may affix a deviant label."

Lest anyone should doubt the value of the labelling theorists argument that the deviant is one to whom the label has been successfully applied, the following quote from the column of the British Medical Journal entitled 'Any Questions?' offers one of the clearest examples of the process in operation. One of the questions asked by a doctor to the 'Any Questions?' panel was, "What procedures, therapeutic or statutory should a G.P. follow when confronted with an addict?" The reply was that "G.P.s are seldom called upon to do more than persuade the patient to enter a suitable institution . . . If the patient proves completely unco-operative it may be necessary to invoke the aid of the law to apply compulsion . . . Since most of the drugs concerned are included in the scope of the Dangerous Drugs Acts 1920-1925, it is often possible to prove an offence against these Acts for which the patient may be summoned before a Magistrate."! 3 (Italics mine.) In other words, if the patient is co-operative the label will not be applied — if he is not, we will call him criminal.

However, whilst acknowledging a debt to the labelling theorists for drawing attention to this phenemona, the point for our purposes is to examine the effect official figures have had on the legal framework. By 'effect' I mean that we can accept the labelling theorists' arguments as such and notice how official figures have been classified and then show how these have been used for policy decisions.

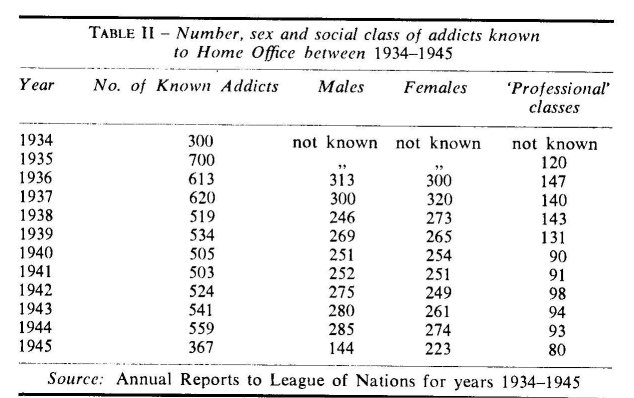

We can divide the period 1920-1970 roughly in two parts; from 1920-1945 and 1945-1970. First the period 1920-1945. Table II shows the number, sex and 'social class' of known addicts, and Table III shows the prosecutions for drug offences. There are no available figures for known addicts prior to 1934.

It will be seen from Table II that the period between 1934 and 1945 was one of steady decline in the number of known addicts. There was a slight rise in the latter half of the war followed by a decrease in 1945. It will also be seen that the male/female ratio is fairly even throughout with males being slightly more pre-dominant. In 1945 the position changed, for no very clear reason, but whereas the numbers of males appear to fall by about 50%, there was a much smaller decrease in female addicts. The per-centage of "professional classes" remained fairly steady through-out, from about 24% in 1936 to about 18% in 1940 and to about 22% in 1945. This group of "professional addicts" consists mainly of doctors, e.g., of the 143 professional addicts in 1938, 134 were medical practitioners, 5 were pharmacists, 2 were dentists and 2 veterinary surgeons.

The figures appear to justify the optimism of the Rolleston Committee as from 1935 the number of known addicts declined. The annual reports to the League of Nations in the 1930s always stated that "drug addiction is not prevalent in Great Britain" and from these figures it appears that this was so. No detailed records were kept of the drugs used during this period, but most appear to have been addicted to a single drug which in the majority of cases appears to have been morphine, e.g., in the Annual Reports for 1936, 72% were said to be addicted to morphine, 17% to heroin and 8.5% to cocaine.

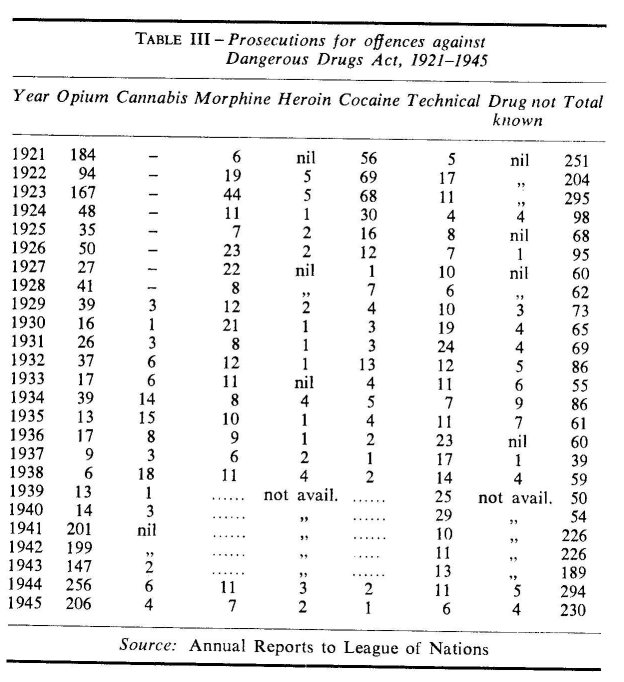

The other main source of information, the record of prosecu-tions, is shown in Table III. Here, official figures are available from 1921-1945, except for prosecution for offences involving morphine, heroin and cocaine during 1939-1943. No reasons were given for this omission in the Annual Reports, but it may have been one further element of caution during the early war years. It should also be noted that the figures in this table relate to prosecutions rather than convictions.

The figures in Table III give a few more details about these offenders than there were for the known addicts shown in Table II. We know something about the ages and countries of origin of these offenders after 1926 when the Annual Reports were made public. Even so, the amount of information is still very limited. For example, no details are given about the areas of Britain in which the offenders for manufactured drugs occurred, or how many of those known addicts were ever prosecuted for drug offences. In other words, there is no way of linking the two tables.

It will be seen from Table III that the total number of prosecu-tions for all drugs fell considerably after the 1923 Act and it was not until the Second World War that they approached the pre-1920 figure. The increase in opium prosecutions during the war years has been attributed to an increase in the Chinese population in areas like Liverpool after shipping routes from the Far East had been diverted to United Kingdom ports. It had always been considered in Britain that opium offences were committed by persons of Chinese origin living in or near the large ports. An increase in prosecutions up to 1945 was therefore seen as a reflection of the increase in the Chinese population rather than an increase in the use of opium by the indigenous population. The Annual Reports for 1943 put the position clearly, if not a little complacently. "Opium smoking is essentially a habit of Eastern peoples and it is unlikely that a market can be found for the drug among Europeans in this country."

It will be seen also from Table III that prosecutions for can-nabis up to 1945 were low, even during the war years. Offenders were almost always foreign coloured seamen, although there were very occasionally a few white British citizens too.

Prosecutions involving manufactured drugs also declined after 1923. Table III shows that prosecutions for cocaine in the early 1920s were easily the most numerous. By 1926, however, there were more prosecutions for morphine and this pattern continued throughout the period. There were always a very small number of prosecutions for heroin, which fits in well with what the Home Office thought was the pattern of use during that period.

In Table III "technical offences" refer to offences such as failing to keep a register and apply mainly to doctors and pha'r-macists. The number of these also decreased after the 1923 Act in spite of the small increase in Regulations following the 1925 and 1932 Acts. Only rarely were these offenders sent to prison, the most usual penalty being a fine of less than £10.

Because of the relatively small numbers of prosecutions per year, especially for the manufactured drugs, it is perhaps more fruitful and simpler to see the period as a whole, rather than become involved in detailed analysis with a very small number of offenders. As it is there was no information on these offenders for the period 1920-1925, and that which is available after 1926 is confined to age and sex with some additional facts about the offenders' occupations. Altogether there were some 3,155 persons prosecuted for drug offences between 1920 and 1945, and 2,139 during the period 1926-1945. If we concentrate on the latter group of 2,139, then in terms of the sex distribution only 123, or 5.7% of these were women. About half of these were listed as nurses, doctors, dentists or chemists; the remainder were shown as being housekeepers or as having 'no occupation' which probably meant they were housewives. These women offenders were usually prosecuted for offences relating to manufactured drugs, such as morphine or heroin, but occasionally for cocaine. As far as the prosecutions for heroin and morphine were con-cerned, women accounted for nearly 50% of these during this period, and only rarely were they prosecuted for offences involv-ing opium or cannabis. On the odd occasions where this occurred, they were almost always in the younger age group: i.e., 20-40, in contrast to those prosecuted for morphine and heroin offences where they were usually aged 40 or over.

Taking the figures for both sexes together, the mean age of all offenders appears to have been about 40, e.g., only 11 of the 2,139 were under the age of 20 and only 299 were under 30. The age distribution appears to have remained steady throughout, and even during the war years there was no tendency for offenders to be younger.

The data on the occupations of these offenders do not appear to have been collected in any systematic way, and it is not possible to think in terms of classifying bv social class. The largest listed occupation group were 'seamen', but these included ships' officers as well as deck hands. This group was by far the largest, accounting for 1,300 or 65% of all offenders, or 75% of all male offenders. The next largest listed groups were chemists, 203 or 9% and doctors 143 or 6%—who were mainly prosecuted for 'technical offences'—but there was a group of 371 persons who were listed as being in 'other occupations'.

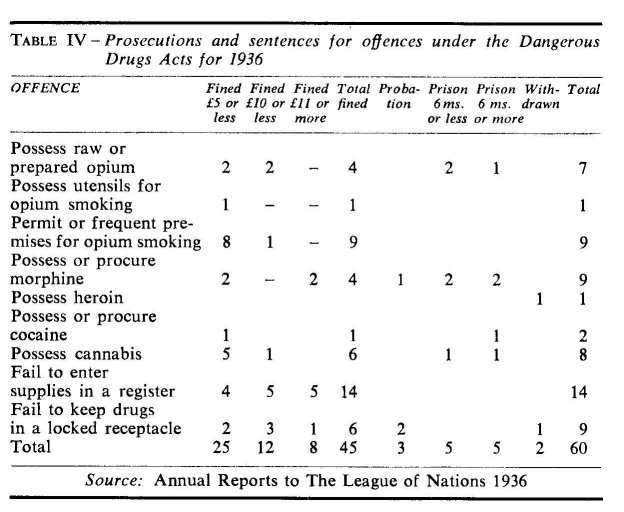

The pattern of sentencing remains fairly similar throughout this period, the majority of drug offenders being fined. If a sen-tence of imprisonment was passed it was unusual for it to be more than 6 months. Even during the war years when there was an exceptionally large increase in the number of opium offenders, there were no demands for more severe penalties as was the case in 1916 or in the 1960s. Most were fined £10 or less, and in many cases £5 or less, e.g., in 1942, out of 226 offenders for that year 171 or 75% were fined £5 or less. Table IV gives a more detailed breakdown of prosecutions and convictions for 1 selected year, in this case 1936, and it can be seen from this table that 45% were fined, most of these for amounts of £10 or less, and 10 were sentenced to imprisonment, but 5 of these for less than 6 months. In this year there were 57 males and 3 females prosecuted, and 9 offenders were under 30. Their occupations were listed as Seamen 24, Medical and allied professions 30, and Others 6. The year 1936 has no special significance and was chosen only because it is the mid-point of the period 1926-1945.

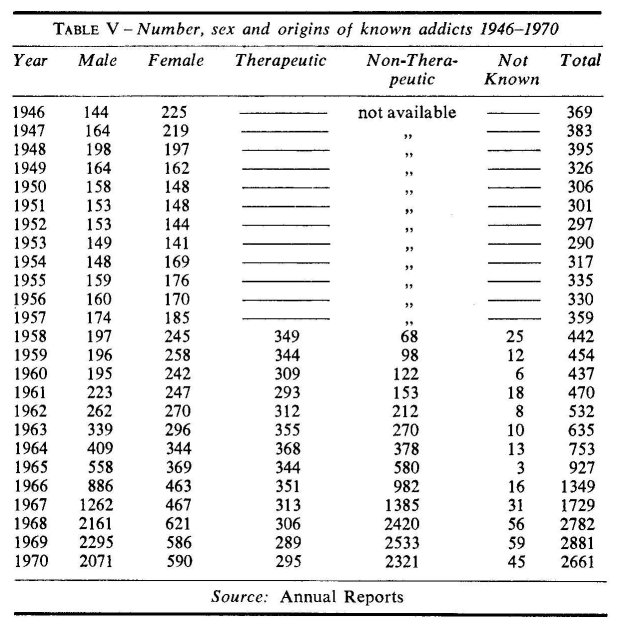

Table V gives the number, sex and origins of known addicts from 1946-1970.

Table V shows that the total number of known addicts declined from 1946 to 1953. From 1953 there was a steady increase until 1961, but then it became much more rapid until 1968 which showed the largest annual increase of all. 1970 shows a change; here the curve is beginning to level off. In fact, by 1970 there had been a decrease for the first time since 1960. The period after 1953 coincided with the increase in other types of drug taking, and provided the first concrete arguments for those who saw the beginnings of a changing picture. The tables also show that there were other important changes in the type of person who became a known addict, all of which fitted in with the events of the early 1950s.

a) Sex. Table V shows that from 1946 to 1964 females out-numbered males, apart from the 4 years 1949-1953. After 1963 the number of male addicts increased at a much faster rate, and by 1969 were 4 times greater. For the period 1961-1970 male addicts increased by about 10 times, whereas female addicts had only doubled. After 1969 when the curve begins to level off, the number of male addicts has still continued to increase, but there has been a fall in female addicts.

b) Medical origins. Table V shows the medical origins of addicts divided into therapeutic and non-therapeutic groups. Details were not available before 1958, but in that year over 80% of all known addicts were classified as "therapeutic" in origin. This therapeutic group has remained steady throughout, and if anything has tended to decrease. The increase in known addicts therefore was entirely accounted for by the non-therapeutic group which increased from 68 in 1958 to 2533 by 1969.

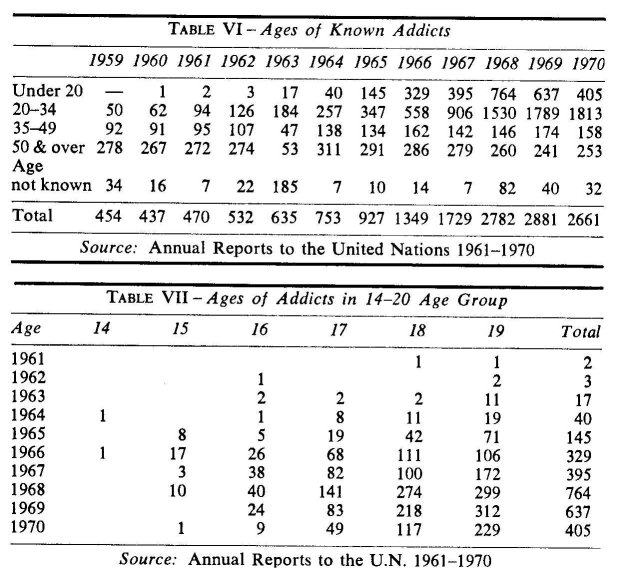

c) Age. Table VI gives the ages of the known addicts after 1959. In 1957 and 1958 the annual reports state that although "detailed information about age grouping is not available, the majority of addicts are over 30 years of age". The reason for not recording this information was said to be due to the small number of known addicts in the United Kingdom at that time. Table VII gives a breakdown of the ages of addicts in the 14-20 age group.

Table VI shows that in 1959 there were no known addicts under 20, the majority being in the age group 50 and over, but there were 50, or 11.1% in the 20-34 age group. By 1960 one addict was under 20 and those in the 20-34 age group had increased to 62, from 11.1% to 14.4%. Unfortunately it is not possible to break down the age grouping further as the Home Office did not keep detailed figures until 1967. Table VI shows that the age group below 35 almost entirely accounted for the increase in known addicts; in 1961 there were only 96 or 20% under the age of 35; by 1969 there were 2426 or 84%. There was also a small increase for those aged 35-49 during this period, but a decrease for those over 50. Table VII shows a steady increase in the number of addicts under 20 from 1960-1968. However, after 1968 there appears to be a fall, and for the first time since 1963 the 1969 and 1970 figures give no new young addicts aged 14 or 15. This table would be used to support that note of "cautious optimism" sounded by the Home Office in the 1969 report as it suggests that as there are no new young addicts being recruited, those already in the under 20 group will eventually work their way out through this age group.

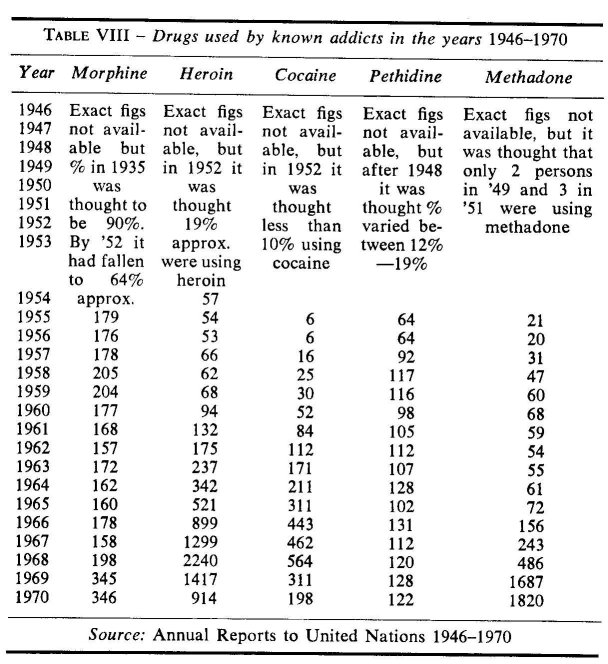

d) Drugs used. Finally, Table VIII shows the drugs used during this period.

Where a person has used more than one drug he has been listed under both headings. The annual totals for drugs used during each year will not therefore correspond to the numbers of known addicts. Table VIII shows that morphine was the drug most widely used up to 1957 and was by then used more often than all the others together. However, the number using heroin gradually increased after 1956 and a large increase occurred in 1960. There was a similarly large increase in those using cocaine, but this was almost entirely accounted for by the increase in heroin addicts who were also using cocaine, i.e., in 1959 18 addicts were using heroin with cocaine; in 1960 this number had increased to 44. Also in 1960 there was a corresponding decrease in those using the more 'traditional' drugs such as morphine and pethidine. The same pattern continued during the 1960s and by 1962 heroin had become the drug most widely used. However, in 1969 methadone (physeptone) became the drug most widely used and this almost certainly reflects the policy of the treatment centres of prescribing physeptone rather than heroin.

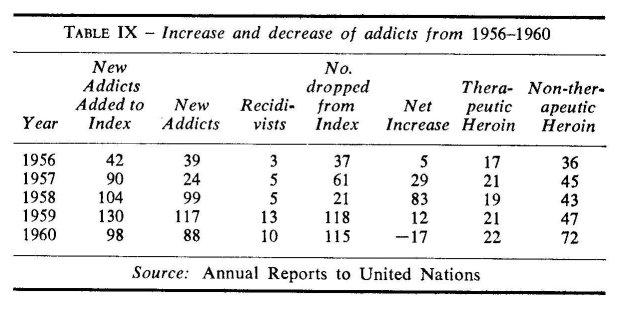

e) General. These tables show how the recorded increase in drug taking was accounted for during the 1960s by the non-therapeutic young male heroin addict group. They also show that the years 1965 to 1967 were crucial in the sense that this was the period when the percentage increase in known addicts was greatest, and it was then that a certain amount of government initiative was thought to have been lost by failing to implement quickly the recommendations of the second Brain Committee Report. Table IX shows the increase in the number of known addicts after 1956, but these are of course net increases, and stated this way mask the gross figure whilst still showing an increase. Table IX gives additional details showing how this gross increase was offset by similar increases in the large number of older addicts, mostly therapeutic in origin, who were classified in the Annual Reports as being "dropped from the Register" as a result of death or being cured. The last 2 columns list the new heroin addicts in terms of their origins. The total for column 5 is arrived at by deducting column 4 from column 1.

It can be seen from Table IX that the figures show an important increase in non-therapeutic heroin addicts after 1956 offset by an unprecedented number of addicts dropped from the Register in 1959/60. In the light of this table it is perhaps not surprising that the first Brain Committee's Report in 1960 was treated with such scepticism.

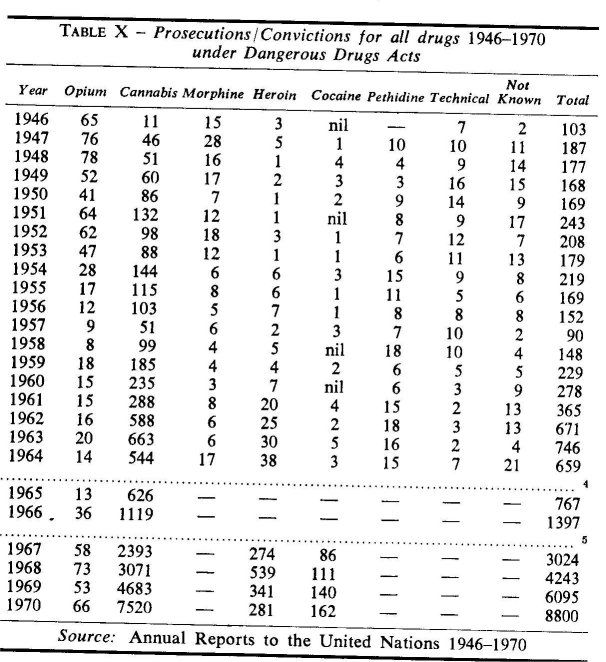

If we now examine the Criminal Statistics for drug offences (Table X), the first point to note is that like the Home Office figures these too offer a limited source of information. In the first place there are no figures for convictions for drugs such as morphine and pethidine, nor for the technical offences, after 1964. Secondly the figures for the years 1945-1954 are for prose-cutions, but from 1955-1970 they are listed as convictions. In the analysis that follows I have grouped morphine, heroin, cocaine and pethidine and called them manufactured drugs, but opium, cannabis and the technical offences have been examined separately. The category listed as "not known" also includes those cases where a person is charged with possessing more than one drug. It is not clear why the annual reports included these in this category, nor why having once included them no further details were given.

a) Opium. It will be seen that the number of opium offences show a steady fall throughout this period, especially when com-pared with the figures for the war years. In 1960 the annual report noted that "the use of this drug is confined mainly to persons of Chinese origin." 9 of those 15 convicted were Chinese, but 5 came from Pakistan and India, and 1 from Egypt. In 1966 there had been a further increase which was thought to reflect the poly-use amongst British drug takers rather than an increase amongst the Asiatic population.

b) Cannabis. In direct contrast, prosecutions/convictions for cannabis up to 1951 show an irregular but important rise. There-after the unevenness almost certainly reflects police activity, but the trend seems to be clear, especially after 1957. In 1950 it was believed that cannabis use was increasing, but some overall account must be taken of police activity as with other drugs, because in the last few years special drug squads have been formed due to public and Parliamentary pressure.° After 1965, however, the number of cannabis offenders increased at a rapid rate, the largest annual increase occurring in 1967 with over 100%, although the 1969 figures still showed an increase of 52%. Most of these convictions were for unlawful possession of cannabis; 4094 in 1969 or 85.2%, and 2663 in 1968 or 85.5%. The remainder were mainly for permitting premises to be used for smoking cannabis, for unlawful import and unlawful supply.7

A more detailed an'd comprehensive survey of cannabis offenders appears in a report by the Advisory Committee on Drug Dependence (the Wootton Reports) In their analysis, the Committee found that 2419 out of 2731 charged with possessing cannabis had less than 30 grams in their possession, and of these 2419 offenders, 373 or 15% were sentenced to imprisonment.° There were 1857 persons without previous convictions for any type of offence who were convicted of possessing less than 30 grammes, but 237 or 13% were sent to prison. The Committee noted that as far as sentencing was concerned there was a notable tendency to place greater emphasis on fines and imprisonment for possession of cannabis than for other dangerous drugs, but less on probation and discharge. As far as the ages of those charged with possession were concerned, 1791 or 66% were under 25, and of those over half (990) were under the age of 20. The Report also showed the pattern of the increase in white offenders to have continued during the early 1960s, and by 1964 for the first time white persons outnumbered coloured. Three years later there were almost 3 times as many white offenders as coloured, i.e., 1,737 white and 656 coloured.

c) Manufactured drugs. Convictions for manufactured drugs (i.e., morphine, heroin, cocaine and pethidine) up to 1960 show a less clear picture, but the numbers are still very small. As far as is known those convicted for heroin offences were then mainly known addicts who tried to get extra drugs by false prescriptions or extra supplies from more than one doctor. From 1950 to 1955, 18 persons were convicted of 24 offences and of these 18, 15 were known heroin addicts. It was not thought that there was a substantial hidden addict population." Similar details are not available for 1955-1960, but the annual reports state that offenders were still thought to be 'known addicts'. Some cases of illicit trafficking occurred, but these mainly involved drugs which were stolen in Britain as a result of breaking into chemist shops. The reports for the period note that "there was no evidence to suggest that manufactured drugs were illicitly imported into, or illicitly produced in the United Kingdom."" In this sense there was no evidence of organised crime on the American pattern.12

After 1960, convictions for heroin and cocaine steadily increased although as has already been pointed out the convic-tions for heroin fell in 1969 for the first time for over 10 years. This decrease was thought to be related to the policy of the treatment centres not to prescribe heroin, but it should be noted that there has been a corresponding increase in convictions for other drugs, particularly physeptone. The implication here is that convictions are related to domestic supplies, rather than to illicit imports. The Annual Report for 1969 states that "manu-factured drugs seized by the police during 1969 were almost entirely of licit manufactured origin", but in July 1969 the Home Secretary reported that "the police have reported 36 persons arrested for possessing heroin not licitly manufactured in this country as well as two seizures of heroin from Hong Kong sea-men." These were the first important seizures of illicit heroin ever reported and almost certainly reflect the treatment centres' policy of substituting physeptone for heroin. Convictions for other manufactured drugs such as morphine and pethidine have remained low and no other details are available.

d) Technical offences. The number of 'technical' offences almost always involved cases of failing to keep drugs in a locked receptacle, or maintaining appropriate records. As far as can be seen, all these convictions resulted in a fine. Those con-victed were always said to be "British subjects of European origin", i.e., white instead of coloured. The number of technical offences, like all other convictions, may also reflect police activity. Doctors' and pharmacists' records have been regularly inspected for 4 decades, but it is still not known what happens if an offence is discovered. Do the police employ a cautioning procedure, or is every offender immediately prosecuted? Neither is it known how strictly or regularly pharmacists' records have been inspected or how efficient the police have been in detecting offences. In 1920 when they first inspected records, there were less than 10 drugs controlled under the Act; in 1960 there were 65 and by 1970 over 100. Given the police orientation to 'crime', or as Dr. Chapman suggests, dealing mainly with working class property offenders, it is reasonable to suppose that inspecting these records would be likely to be unpopular with some police authorities." It might also be difficult for them to deal with persons of higher social class, who would be talking about a 'pro-fessional' and technical matter. In Canada, officers of the Central Government inspect pharmacists' records as well as manufac-turers' and wholesalers', who are required at fairly frequent intervals to submit details of all transactions involving dangerous drugs. This system at least avoids some of the problems which the police seem to experience in Britain.

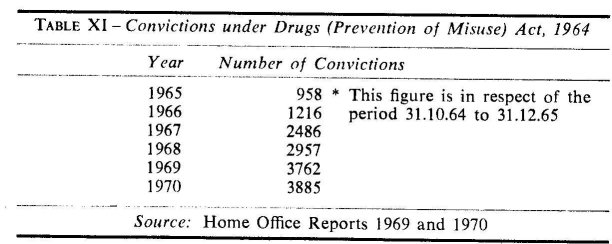

e) Convictions for offences under the 1964 Drugs (Prevention of Misuse) Act. One further group of offences not listed in the Annual Report is that involving offences under the 1964 (Pre-vention of Misuse) Act. Details are given in Table XI below.

The Report of the Advisory Committee on Amphetamines and LSD notes in p aragraph 24 that the figures show "convincing evidence of the persistence of the nuisance which the Act was designed to combat." There are few details of these offenders, but it appears that 38% of the arrests in 1967 were made in the London area. The figures for 1968 show that convictions for amphetamine offenders were heavily concentrated in the younger age group with 78% being aged 25 or under. As the Advisory Committee points out, these figures do not necessarily reflect the pattern of amphetamine dependence amongst the general popu-lation, as it is the youthful drug taker who is likely to rely on illicit supplies and is likely to appear before the Courts, while his middle-aged counterpart has a better chance of obtaining supplies on medical prescription. It was noted, for example, that in a study of 498 hospital admissions for persons using amphetamines, 50% were under 25, compared with 78% under 25 who were convicted. Similarly, in 1968 there were 72 convictions for possessing LSD, 52 of which were for people in the under 25 age group.

f) General. Although it may be accepted that drug takers in Britain tend to be 'poly-users', it is not known how many of those convicted for drug offences have other convictions for different drugs. The annual reports and the figures for convictions under the 1964 Act do not relate these to persons, yet of the 72 con-victed for LSD, 9, or 12% had convictions for previous drug offences, not necessarily for LSD. It is not known how many of the known addicts have drug convictions, either for their drug of addiction or for different drugs, but it is important to ask if some drug users are more prone to conviction for drug offences than others. Perhaps homeless drug users are more likely to be convicted than those living with their parents, not because they give away or even sell more of their prescribed drugs, but because their offences have high visibility. The main features of those tables are firstly, that the drug takers who had been labelled 'addicts' or 'criminals' are predominantly those coming from the younger age group, and secondly the vast increases in the numbers involved, the changes in the sex distribution, and the types of drugs used.

These then are some of the features of the known addicts and the drug takers who were labelled criminal deviants. We are not concerned here to establish how the labelling process operated but to point to this group as being the one about whom legal decisions were made, which in this sense is to make a fine distinction between the sociology of deviancy and the sociology of law. The Home Office figures and the Criminal Statistics pro-duced the background to the legal norms although of course the way they were collected, and presented too for that matter, has had some influence. In the remainder of this chapter I want to link the Official Statistics with the legal process and compare the drug takers in the pre-war period with those of the post-war era.

The data presented on the drug takers during the 1930s shows that they were mainly middle aged, predominantly from the professional classes and were usually addicted to morphine. They were evenly distributed in terms of sex and were incidentally thought to be secretive in their habit and widely scattered throughout the country. They were relatively infrequently con-victed for drug offences; the drug offenders themselves were predominantly Chinese seamen who smoked opium.

Compare this group with the post-war era. Up to 1960 the pattern remained as before but thereafter the majority were heroin addicts, or young amphetamine, LSD and cannabis users who tended to be convicted for drug offences (see also Appendix III), and to congregate in certain selected areas—particularly Piccadilly Circus and Notting Hill. They were much younger, and predominantly male. They did not come from the profes-sional classes. In short they were in every way the antithesis of their pre-war counterparts. These factors in themselves were important enough to suggest a change in the pattern, but when these are added to the inferences that were drawn about the pre-war drug takers the link between the official statistics and the legal norms can be drawn.

My argument then is that changes in the system of control occurred as a result of the new type of known drug taker. Inevitably such an argument will be attacked on the grounds that the composition of the drug taking population was less important than the quantity of drug takers in the 1960s. Whilst sympathising with this point of view it is important to note that demands for controls occurred long before the numbers of known addicts reached the 1930s figure, and it was not until 1964 that they had overtaken the figures for 1937. With 500-600 known addicts in the 1930s, drug taking, according to the official reports, was not a problem in Great Britain.

As far back as 1950 some authorities believed that a new type of drug taker was beginning to emerge. The annual reports for that year noted that "the traffic in hemp is of much greater importance in the United Kingdom than the traffic in opium." It was thought that an increase in the number of prosecutions in 1950 was in part "a reflection of increased realisation by the police of the problems involved", but it was also believed that the traffic had spread for the first time away from the dockland areas to other parts of the country where there was a large coloured population. In 1950 there was also evidence that can-nabis was being smoked by the white population in the West End of London. The first piece of information was given when a ship's steward was arrested in Southampton for possessing can-nabis and said that he usually smoked it in a particular West End dub. This club was subsequently raided by the police; 10 men were charged with possessing cannabis and cocaine, and a further 23 packets containing cannabis were found on the floor. All but one of those charged were between 22 and 29 years of age and, contrary to the normal experience, only one was coloured. H. B. Spear reports that the first teenage offender to come to the notice of the Home Office was arrested in 1952 for póssessing cannabis. He was then 18 and said he had been smoking it since he was 16+. Over the next 8 years there was a steady increase in convictions amongst the white population. Nevertheless, by 1960 the annual report still said that most of the offenders were of African or West Indian origin.

There was some pressure to bring to the public's attention this "rapidly developing craze by the young people for doped cigar-ettes." In the House of Commons in 1951 the Secretary of State for the Home Department was asked if he was aware of "the public concern at the increased practice in trafficking in drugged cigarettes." A book published in 1952 entitled "Indian Hemp—A Social Menace" 14 was aimed at arousing public interest in what one reviewer in the British Medical Journal called "the possibility of an increase in the dope peddling of Indian Hemp in this country." In spite of this agitation, only a few people regarded the warnings as serious.

Many of these fears were confirmed by an earlier incident in 1949 when approximately 1,200 grains of morphine and 14 ounces of cocaine were stolen from a wholesale chemist in the Midlands.15 Most of these drugs were subsequently sold to known addicts in the West End who were already receiving legitimate supplies. Important though this case may be, there did not appear to be any attempt by those known addicts to resell any of the drugs, nor did the person who stole them appear to sell to anyone who was not already addicted. Spear reports that "a careful examination of the background of those morphine addicts who did appear in 1950 and 1951 failed to reveal any connection with him." 16 Much more important was the second case of trafficking which occurred in 1951 when approximately 2,400 grains of morphine, 500 grains of heroin and 2 ounces of cocaine were stolen from a hospital dispensary near London. Although the full extent of this offender's activities will probably never be known, the police were able to name 14 persons who were believed to have obtained drugs from him. In contrast to the earlier case, only 2 of these had previously been recorded as known heroin addicts, although some were known to have used cannabis and cocaine. This appeared to be the first example of large scale trafficking which involved selling drugs to non-addicts; prior to this the addict population was thought to have been content to retain their drugs within their own drug taking group. It is also of interest to note that the police recovered all the stolen morphine but very little of the heroin and cocaine, suggest-ing that the latter drugs were now becoming more popular than morphine.

Another important change was the increase in the use of amphetamines. Evidence of widespread illicit use began to reach the Home Office by 1962, but some authorities believe that the increase occurred in the early 1950s. In fact some signs appeared as far back as 1939 when benzedrine was placed on Part I of the Poisons List under the 1933 Pharmacy and Poisons Act, due to an increase in demand. In 1954 as a result of a further increase, all amphetamines and their salts were placed on Schedule 4 of the Poisons List which meant they could then only be sold by retail chemists on a doctor's prescription. This increase in use was thought to be part of a world wide pattern, as in 1956 the W.H.O. Expert Committee on Drugs Liable to Produce Addic-tion reported that the abuse of amphetamines had already begun to constitute a hazard to public health in some areas." Finally, in the second half of the 1950s, there was also the increase in known addicts which occurred at about the time the first Brain Committee reported but which the Brain Committee decided to ignore.

It could of course also be argued that the method of collecting the figures underestimated the extent of addiction in Britain in the 1960s. If this is so, and many research workers have attempted to give incidence and prevalence (see Appendix III) then the same position applied in the 1930s too. In fact the method of recording in the 1930s was probably worse than for the 1960s, and where attempts were made to provide data on the extent of addiction they were made in a half hearted way. The first official estimate was in 1931 when it was reported in a discussion on drug addiction that "the Home Office *know the names of 250 addicts and the number was probably not much greater." In 1934 it was thought to be about 300, but an estimate in 1935 put the number at 700.

One explanation for the lack of figures in the 1930s is that Britain was not required to provide annual statistics on the number of opiate and cocaine addicts to the League of Nations until 1937 although the Advisory Committee began to show an interest in annual returns as far back as 1930. However, after 1937 annual returns were made to the League although it is extremely doubtful if the figures have very much value, largely due to the manner in which they were collected or recorded. In 1934 a card index system was started which had a small amount of information recorded either as a result of regional medical reports following the inspection of doctors' records, or as a result of the Home Office Drugs Branch's own inspections. From 1934 it was the practice to record the names of addicts for the annual returns as long as some new information about their drug taking was available within the last 10 years. After 1944 this policy was changed and names were removed if nothing new was heard for a period of 1 year from the time they were said to be cured. The result was a large fall in the number of recorded addicts from 599 in 1944 to 367 in 1945, but there are grounds for believing that this policy was still not strictly adhered to as it was discovered that some addicts were still being recorded although nothing had been heard of them for at least 5 years. It is therefore extremely doubtful if the new index was very much more accurate than its predecessor, and it was not until 1957 that clearly defined procedures were introduced and carried out.

Apart from the Home Office itself, other officials such as the police did not appear to concern themselves with helping to produce a more accurate record system. The police had a duty to inspect retail chemists' records, but no general request was made until 1939 for them to notify the Home Office. Then a manual entitled "Notes for the guidance of police officers" asked them "to keep the Home Office informed of all persons who are having regular supplies of dangerous drugs." 18 The reason given was that "this information is of vital importance to the full control of the use of drugs in the United Kingdom." Guidance was also given as to the types of supplies which were to be reported. Even so instances still occasionally came to the notice of the Home Office in which supplies had been made regularly for several years without being reported. In the 1950s another manual was produced giving sterner and more concise instructions.

How then did the Home Office get its information at all? Mainly, it seems by drug takers reporting themselves, but their reasons for doing so remain obscure. No apparent benefits were available after they had told the Home Office as they could receive their supplies whether the Home Office knew or not. More important, however, is the point that the addicts did report themselves, as this shows a trust and an affinity with government agencies which suggests a form of consensus about the addicts' position and the social control agents.

After 1945 the Home Office still had to rely on information given to them by the police as a result of inspection of records or by their other contacts with drug takers. Occasionally infor-mation was given by other agencies such as the Probation Service, but this depended on the decisions of individual Probation Officers. After 1945 and right up to 1970 some drug takers con-tinued to report themselves, sometimes in the mistaken belief that if the Home Office knew they were receiving drugs from a doctor they were 'registered' and could not be prosecuted for having these drugs in their possession. No such registration pro-cedure ever existed; if drugs were being received from a doctor there could be no prosecution anyway. It was not until 1968 that new regulations became operative, so that until then the method of compiling the Home Office figures was still fairly haphazard.

After 1967, when the Act introduced compulsory notification, "any medical practitioner who attends a person whom he con-siders, or reasonably suspects to be addicted to any drug specified in the Schedule to the Dangerous Drugs Act 1951 [is required] to furnish particulars of that person to the Chief Medical Officer, Home Office." This regulation at least provided a standard for-mat for notification, but whether it was faithfully adhered to is another matter. Notification is still dependent on the user coming into contact with a notifying authority and that authority defin-ing the user as a suitable case for notification.

It is interesting to compare these requirements with the Rolleston Committee's views on notification, as they had rejected it on the grounds that it was 'unnecessary'. It seems to be one of the features of giving official recognition to a new social problem that the agents of social control invariably require 'more infor-mation'. Whether this is for the sake of future decision making or a device for avoiding present decision making is as yet un-clear, but it seems to be a factor which social theorists might well consider.

It is also important to note that the numbers of drug takers have never been the sole criteria for control. Apart from alcohol and tobacco, barbiturates are, after all, still the most widely used drugs—but the 1970 Act did not include those in spite of their addictive propensities being well known. As far back as 1950 there was evidence that barbiturates produce very serious physiological effects. "The abstinence syndrome is characteristic and dangerous . . . [compared with morphine] . . . barbiturate addiction is a more serious public health and medical problem because it produces greater mental, emotional and neurological impairment and because withdrawal entails real hazards". In 1968 there were 15-17 million prescriptions for barbiturates with an average of 80 tablets per prescription—or 4 times the fatal dose. The total number of barbiturates prescribed per year then is 1,360 million tablets. The number of amphetamines used by young people was never thought to be anywhere near this figure, nor were the amounts of opiates, yet amphetamines were strictly controlled in the 1960s.

The agitations for change in 1959 were not then based solely on a view that addiction was increasing but that alterations were taking place in the patterns of drug taking. Those agitating for change did so in ways similar to that of all moral entrepreneurs; they wanted 'action' and something done about a new social problem. By the mid-1960s when the numbers of known addicts had gone far beyond the totals for the 1930s there were justifica-tions for change but, even so, changes still occurred amongst a highly selected group, i.e., the young drug takers rather than the older barbiturate addict.

It is not my intention here to invoke a generation gap type argument, although such an argument would not be without its merits. Rather I am concerned to link the change in legislation and the change in the composition of drug takers with Joseph Gusfield's notion of moral passage.1° Gusfield's argument is similar to the point made by David Downes and Paul Rock when they state that "where hostility to the very basis of social norm is imputed to the deviant, societal reaction of a much more puni-tive kind is seen to be justified. Conversely contriteness on the part of the offender and co-operation with the police and welfare agencies can promote re-categorization of the deviant into a more acceptable role." 2°

Gusfield's analysis of deviant behaviour in terms of the re-action of the designators to different norm sustaining implications of an act is particularly pertinent here. He classifies behaviour into 4 types based on the symbolic character of the norm itself.

The first type is the repentant deviant. Deviation for this type is seen as a moral lapse, a fall from grace to which the deviants aspire. The repentant deviant admits the legitimacy of the norms and by so doing produces a consensus between the designator and the deviant. In other words this repentance confirms the norms.

The second type is the cynical deviant. His basic orientation is self seeking but he does not threaten the legitimacy of the normative order. His behaviour calls more for social manage-ment and repression.

The third type is the sick deviant. He neither attacks nor defends the norms as his behaviour is neutralized by being seen as uncontrolled and therefore irrelevant.

Finally there is the enemy deviant. He accepts his own behaviour as proper and derogates the public norms as being illegitimate. He refuses to internalize the public norm into his self definitions.21

It is the fourth type, the "enemy" deviant who particularly concerns us here, although the "sick" deviant is not without interest for our purposes. The importance of the enemy deviant is that his refusal to accept the public norms as legitimate means that when the public norms are attacked the designators need to strengthen and reinforce them. They can do this by a variety of methods, one of which is to strengthen them by legal changes, reinforced by moral sanctions.

We can illustrate Gusfield's argument by pointing to the shift in designation of the drug takers from being repentant deviants in the 1930s to being the enemy deviants of the 1960s.

To some extent the Chinese seamen convicted for opium were nearer to the cynical deviant in the sense that their behaviour was self-seeking without threatening the legitimacy of the nor-mative order. Their behaviour was not seen as being a product of British society anyway since they had acquired the habit elsewhere. They were often transients, and according to the official reports had no interest in converting the indigenous population to drug taking. In other words they simply wanted to be left alone. To describe them as 'cynical' is perhaps in-accurate, they really constitute a fifth type of deviant, the cultural isolates, so that their behaviour was condemned but also excused on cultural grounds. Had they proselytised drug taking amongst the indigenous prpulation, as did the West Indians with cannabis in the West End clubs, then they could easily have been transformed into enemy deviants.

The 'real' drug takers of the pre-war period, the middle aged housewives and the group from medical and allied professions, were no threat to the value system either—though for different reasons. As members of the medical and allied professions they 120

obviously wanted to keep their habit secret and be allowed to continue with their work. Interpretations and explanations of their addiction are an important indication of societal reaction—a point we shall return to later when we examine classificatory systems—the point here is that this group of addicts were seen as having become addicted through contact with drugs rather than contact with drug users and drug values, particularly sub-terranean values which were imputed to the post-war group. The housewives were seen as 'therapeutic' addicts, but both groups had their behaviour interpreted as typical of repentant deviants who were good citizens in all other respects but had unfortunately become addicted. They were pitied rather than condemned, and like all repentant deviants were seen as having fallen from grace, or having had a series of moral lapses.

This group fitted in well with Rolleston's definition of addiction and the Committee's interpretation of addictive behaviour. Rolleston saw addiction as occurring amongst people who had work which involved much nervous strain, rather than amongst groups who pursued the habit for pleasure or who were members of the 'criminal classes'. Such a view could lead to an overall impression that drug taking was not a problem and permit a complete lack of interest as far as drug taking was concerned. In this way those addicted or prosecuted could be dealt with in an unemotional way and labelled in a way which appeared to produce very little stigma. Societal reaction was then one of sympathy mixed with indifference. In this sense, where the Home Office reports stated that drug taking was not a problem, they could equally have said that the drug takers themselves were not a problem either. Their repentance confirmed the norms.

An examination of the reports and convictions confirms this view. Moral condemnation was rarely levelled at the drug taker and sentences of imprisonment were passed only in the last resort. Even during the war years when drug offences increased rapidly there were no demands either for additional punishments or for more information or even changes in the system. Societal definitions of the problem remained consistent and having once defined it in this way it is understandable that the recommenda-tions of the Rolleston Committee were never challenged, nor was there pressure to implement the safeguards of the medical tribunals. Additional protection was seen as unnecessary for this type of repentant deviant. Protection was, however, necessary for the enemy deviant some twenty years later.

Great play was made of the lack of involvement in the illicit trafficking and the drug users in Britain were not thought to be involved in this either. For example, in 1932 the leaders of a gang of drug smugglers visited London. It was thought they had been dealing in enormous quantities on the Continent, running into thousands of kilograms of drugs, but they appeared to have come to Britain only for a holiday! Their business interests were in France, Switzerland, Germany, Turkey, the Far East and the U.S.A. In 1933 a Spaniard, named Gandarillas, was arrested in Southampton in possession of 140 lbs. of opium. He had arrived from Germany on a transatlantic liner and was hoping to transfer the opium to a contact on board, but the plan misfired, and he was left with the goods and no alternative plans for their disposal in Britain.

By the late 1950s the drug takers according to E. M. Schur still came mainly from the middle classes.22 He reported a study of 73 patient addicts at a mental hospital from 1950-1957 and noted that 74% were from middle class professions; there was no predominance of working class addicts. In his discussion with people whom he called "specialists who provided general infor-mation", they too reported a high incidence of middle class addicts. Schur concluded from these studies that age and social class of addicts were closely related, as age was dependent on which class was exposed to drugs. Where drug use began by association with other drug users, as in the U.S.A., the age and social class of the drug taker would be low. Where drug use began as a result of medical prescribing, as in Britain, the age and social class would be higher. In some respects Schur's hypothesis has been validated, but by the late 1950s he was unable to discern a trend already apparent to a number of people who opposed the first Brain Committee. Patterns were changing and producing a shift to the enemy deviant who was prepared to attack the public norm.

Jock Young in his perceptive analysis of drug taking in the 1960s has argued that drug taking is highly correlated with Bohemian Youth Culture where drug use is exalted to a paramount position ideologically and morally buttressed against the criticisms of the outside world.23 Bohemian cultures are according to Young the major growth area as far as illegal drug use is concerned. The Delinquent Youth Culture is also an area of high drug use but Young suggests this is for different reasons. With this group drug use is not only a vehicle for the emergence of subterranean values but, because of the taboos surrounding drugs, is a method of kicking over the traces and seeking forbidden pleasures. The delinquent youth culture centres itself around the various ways available to create a world of adventure, hedonism, 'kicks' and excitement. Drugs, like delinquency, provide the avenues.

This view of drug taking as being located in two distinct youth cultures not only fits in with the changing patterns of drug taking as provided by the official figures but with another piece of research which suggests that drug takers come from two distinct groups, one middle class youngsters, who are ideologically committed to drug taking, and the other working class youngsters who are more antecedently delinquent.24 There may, of course, be some over-lapping here and the typology is crude but the point is still valid. By identifying drug taking in these areas the shift from the 1930s image is almost complete.

To be classified as an enemy it is not enough to be identified with a group, there must be an interaction between the group and the designators. This interaction can take place at varying levels although one important area is the high visibility of the deviancy. The addicts of the 1930s were secretive, and in many cases their families did not know they were addicted. The 'pro-fessional' addict, such as the medical practitioner having probably acquired his habit through contact with drugs rather than drug users, would take his drugs, and continue working as before. In the 1960s addicts were no longer secretive, nor did they continue as before.

Peter Laurie has somewhat graphically described the way in which addicts in 1967 openly advertised their dependency on drug use. He says, "It has been remarked that the most striking characteristic of the new adolescent addicts is their desire for publicity. The enquirer thinking that it is going to be difficult to meet drug users, is immediately overwhelmed by their showing off their spiritual sores like mediaeval beggars; willing to discuss their most intimate affairs at exhaustive, and soon tedious length. It has clearly no use being drug dependent in London unless one is seen to be so. . . . It is easy enough by sleeping rough and eating irregularly, wearing dirty clothes and not bothering to shave or comb one's hair to look adequately dilapi-dated. wear these dark glasses' said one who came to tea with me in December 'just so people know I'm a junkie. You've got to work at the image man.' And another, who refused to be photographed with her dark glasses off in case her parents should identify her, insisted on having a picture taken of her eyes—'Them's real junkie's eyes, man' she cried, as she whipped off her shades." 23 Other reporters have noted how easy it is to interview addicts, and few research workers have had difficulty in obtaining a 'sample'. This is not only due to the large numbers, but because there is seldom a reluctance to talk about drug taking. Schur in the late 1950s, however, found it difficult to find people who were prepared to be interviewed.

Laurie also points to the rather dramatic queue of addicts around the all-night chemists in central London as part of the need to be seen and defined as drug takers. He might also have mentioned the ease with which drug takers are caught com-mitting offences against the Dangerous Drugs Act in Piccadilly. It is not quite as Schur suggests that victimless crimes allow both parties to arrange a mutually convenient meeting place away from the gaze of law enforcement officers, otherwise fewer drug takers would be arrested in public places. It may be as important to be defined as a drug taker as to define, both receiving status from the definition. Once visibility is established it then becomes important to establish hostility to the very basis of established norms. Unlike the 1930 drug taker, the 1960 counterpart argues that the 'system' is wrong; cannabis ought to be legalised—it is not as bad as some other drugs, such as tobacco or alcohol, and he is often unrepentant after being convicted. His values are rarely those of the Protestant Ethic which in terms of drug use becomes what one authority has called a form of "pharma-cological Calvinism" or "if a drug makes you feel good it must be bad." 26 Supporters of this ethic stressed the need for indi-vidual achievement and insisted that qualifications, rewards and pleasures should be obtained by social action. Short cuts by means of drugs were 'evil' since they produced the pleasure without the corresponding effort. Drug takers of the 1960s did not appear to support these values; they sought their pleasures and wanted the short cuts. They even wasted these substances when they ought to have been kept for medical use—another anathema to the ethic supporters.

Drug takers in the 1960s use the 'junkie' argot, another feature which was absent in the 1930s. Harold Finestone has described the American negro addict, whom he calls 'the cat', in terms which apply to so many young British drug takers in the 1960s. He sees 'the cat' as one who relates to people by outsmarting them, and with a sense of superiority which stems from his aristocratic disdain for work. In contrast, the 'square' toils for regular wages, and takes orders from his superiors without com-plaint." That few addicts work is a common experience of every Court or social work agency and in one study of a variety of drug users at 2 London Courts, only 21 out of a possible 92 were working at the time of arrest, 18 had not worked for at least 6 months and 9 others had not worked for at least 3 years.28 In a society which stresses the Puritan Ethic, such behaviour is easily seen as attacking a fundamental value.

The drug taker in his quest for the kick'—and especially the kick on heroin— pursues a way of life which provides, according to Finestone, "an instantaneous intensification of the immediate moment of experience".2" This is a further attack on conven-tional society by engaging in pleasure without having had the appropriate previous drudgery. Society's response is either to warn of the dangers of such immediate pleasure, or to attempt to protect the user from himself.

Finestone also notes that the drug user possesses a large, colourful and discriminating vocabulary which deals with all phases of drug experience. As one of the functions of argot according to Ulla Bondeson is to serve as a common emblem, which also serves as a means of identification,"° it defines the drug user's world from the non-user's. Finestone sees drug argot as being more concrete and earthy than the conventional world's, and as such reveals an attitude of subtle ridicule towards the dignity and conventionality inherent in the common usage.

Finally, the drug user's personal appearance seems to be carefully designed to show that he is as far removed as possible from the conventional clean shaven world of suits and polished shoes, which appear to him to be personified in middle class or military values with the corresponding restriction of movement and decisions. It is easy therefore to see why the police are seen as participators in a para-military machine, attending parades, wearing military medals, addressing senior officers as `Sir' and appearing in public in uniform looking smart and purposeful. They appear to represent the antithesis of all the drug user stands for, and for the same reasons the drug user is seen as attacking those very standards which the police must themselves accept and which they represent as "right and correct values". It may be wrong to see these two groups as totally hostile, for each may have a functional dependence on the other and each may respect the other's point of view; the police sometimes may envy the drug taker's 'freedom' and the drug taker may envy the policeman's steady job and freedom from drugs. But at one level both represent opposing value systems and the one is inimical to the other.

It may also be wrong to categorise all drug users in terms of 'the cat'; recent studies in America have shown that there are a wide variety of groups. Alan Sutter's study distinguishes between "The Mellow Dude", "The Pot head", "The Player" and "The Hustler", whilst another study of physician narcotic addicts illustrates that they have little in common with those of Sutter's study." However, the point still remains that whereas the 1930 addict could be seen as a victim of circumstance, the 1960 addict is now seen as having only himself to blame. Equally it would be wrong I think to see all drug takers as having been classified as enemy deviants. Some would be cast as 'sick' although as Jock Young points out humanitarianism at this level can often be a cloak for greater control and a way of neutralizing rebellion. Occasionally the drug taker may be prepared to accept the 'sick' role, but difficulties occur if the acceptance was only temporary and designed to escape a more punitive sanction such as imprisonment. When this happens the designators assisted by members of the helping professions may be misled into thinking the role is permanent. Inevitably designators and treatment officials feel let down when there is no obvious response to long term treatment. Such a reaction will produce secondary effects, one of which is for designators to change their explanation of drug taking and see treatment "as a waste of time". A new designation is then given in terms of the drug taker being "more sick than was at first realized" or as having "more deep seated personality problems than were once apparent". Either way the effect is a redefinition of the classification which in practical terms means that other drug takers appearing at Court wanting the sick classification may find treatment avenues closed.

I have suggested in this chapter that the legislative changes which occurred in the 1960s were primarily the result of a new type of drug taker and that these changes were proposed before drug taking reached what was called "epidemic proportions". I have tried to show that the designation of the drug takers shifted with the changes in the drug takers themselves so that a redefinition of their role was inevitable. David Downes and Paul Rock have argued that where hostility to the very basis of established social arrangements is imputed to the deviant, or where the career possibilities or potential for rapid escalation are perceived as particularly threatening, societal reaction of a much more punitive kind than that measured by the objective character of the offences committed is seen as justified. Although the authors use the work of Dr. Stan Cohen on 'Mods and Rockers', to some extent the same applies to certain types of drug users, especially those in the younger age group. Downes and Rock have made an important point here as most drug taking is now seen as being hostile to the very basis of social arrangements. It is also important to note that the early Drugs Acts imported a system of control, but the agents of social control have not been any less reluctant to deal with infringements; there is much evidence to suggest that international control has been widely accepted in Britain and readily incorporated into the value system and normative structure. In fact, judging by the Home Secretary's refusal to implement the Wootton Report as being part of a "permissive society", it would seem that drug taking has been seen to require considerable controls. Recent Press reports linking illegal Pakistani immigrants with drug traffick-ing—which were later denied— would also suggest that behaviour with drugs opens the way for stronger sanctions against that behaviour. Some sympathy may once have been given to illegal immigrants, but as soon as they have been linked with drug taking this rapidly evaporates. The implications here are enormous, for all deviant behaviour, political or otherwise, can then be neutralised or condemned as being excessively threaten-ing and thus the credibility of what has been said on other matters is reduced.

And yet, this seems to be only part of the picture. We need to examine the drug takers and make links between the way in which some other control agents have contributed to the drug taking problem. I am not thinking here of the police, against whom allegations of 'planting' have been common in recent years, but rather of the medical profession who, after all, have always been the main suppliers of drugs.

REFERENCES

1. Turk, A. T. Criminality and Legal Order, Rand McNally, 1969, p. 8.

2. Kitsuse, J. I. and Cicourel, A. V. 'A note on the use of Official Statis-tics', Social Problems, Vol. 11, 1936, p. 131-138.

3. Letter to Brit. med. J., 1948, Vol 1, p. 133.

4. Details are not available for manufactured drugs for 1965 and 1966. Totals for those years were 101 and 128 respectively.

5. The method of recording was further changed classifying into Heroin Cocaine and others. Figures for others for 1967, 1968, 1969 and 1970 were 213, 449, 878 and 771 respectively.

6. It was announced in the House of Commons or. 24.6.66 that the Drug Squad in London was to be increased to 20 officers. Hansard 1966, Vol. 730, p. 163.

7. In 1969, 225 persons were convicted for premises offences, 122 for unlawful import and 147 for unlawful supply with 95 for other offences. The 1968 figures were 193, 77, 87 and 51 respectively.

8. Cannabis, H.M.S.O., 1968, op. cit.

9. Ibid, Table C, pp. 26-7.

10. Hansard, 16.6.54.

11. Annual Report for 1959, para. 45.

12. In one of the few reports that give ages of offenders for this period of the 208 prosecutions only 62 were under 30, 47 of which were for possession of cannabis. Annual Report for /952, p. 2.

13. Chapman, D. Sociology and the Stereotype of the Criminal, Tavistock, 1970.

14. Johnson, D. Indian Hemp, a Social Menace, London, 1952.

15. See also Spear, H. B. 'The Growth of Heroin Addiction in the U.K.' British Journal of Addiction, 1969, Vol. 64, p. 245-256, op. cit.

16. Ibid.

17. Leech, K. reports that amphetamines were introduced in 1897 and methylamphetamine in 1919, op. cit., p. 21. See also Kalant, O. J. The Amphetamines, Toronto University Press, 1966.

18. Similar manuals have been published in 1947 and 1957.

19. Gusfield, J. 'Moral Passage' in Crime and Delinquency, Bersani, C. A. (ed.) Macmillan, 1970.

20. Downes, D. and Rock, P. 'Social Reaction to Deviance', mimeo paper read to 4th National Conference on Research and Teaching in Criminology, Cambridge, 1970.

21. Gusfield, J. op. cit.

22. Schur, E. M. Narcotic Addiction in Britain and America, S.S.P., 1936, op. cit.

23. Young, J. The Drug Takers, Paladin, 1971, p. 143.

24. Bean, Philip 'Social Aspects of Drug Abuse' Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science, Vol. 62 No. 1, March, 1971.

25. Laurie, P. Drugs, Penguin, p. 51-56.

26. Klernaw, G. 'Drugs and Social Values' International Journal of Nar-cotics, 1970, Vol, 5 No. 2, p. 317.

27. Finestone, H. 'Cats, Kicks and Colour' in Cressey, D. and Ward, D., op. cit., p. 790.

28. The other eight were students or school children. Bean, Philip, op. cit.

29. Op. cit., p. 792.

30. Bondeson, U. 'Argot Knowledge and Criminal Socialization' in Scan-dinavian Studies in Criminology, Vol. 1, Tavistock, 1965.

31. Winick, C. 'Physician Narcotic Addicts' and Sutter, A. 'Worlds of Drug Use', both in Cressey, D. and Ward, D., op. cit.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|