Appendix 3

| Books - The Social Control of Drugs |

Drug Abuse

Appendix 3 PREVALENCE OF DRUG TAKING AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO CRIME

There have been various attempts to show that the official figures grossly under-rate the extent of drug use in Britain in the late 1960s. The methods used to dispute these or to provide a clearer picture have been a mixture of research, pure guesswork, and an occasional attempt to sample a small population and generalise from this sample. The eagerness to show prevalence and incidence has led to some quite extraordinary claims especially where generalisations have been made from small samples.

All epidemiological studies are basically concerned with three operations: first defining a case, second finding all those cases in a population, and finally obtaining reliable information about those cases. The first problem, that of defining a case, relates to all the problems mentioned in Chapter 1 concerning the defini-tion of drug abuse, i.e., what is a drug, and what is abuse? If abuse means taking any drugs controlled by the Dangerous Drugs Act, then everyone who has an injection of morphine for the relief of pain should be included. If it is defined as the non-medical use of drugs controlled by these Acts, then does this include taking 6 tablets a day when the doctor has only prescribed 4? Is a suicide attempt a non-medical use? Are users of ampheta-mines by definition drug takers whether they have been prescribed or not? At what point does the therapeutic addict become an 'addict'? These, and countless other questions often make for difficulties when one wants to make comparisons between various studies as it is seldom clear which definition has been used.

Sometimes research workers have concentrated on one drug, on other occasions they have dealt with a group of drugs such as the amphetamines or barbiturates, with no attempt being made to say which of these have been included. The latter point also makes it difficult to link their work with other similar studies.

The second problem, that of finding all those cases in a population, can be approached in the same way as studies of 'hidden delinquency', with of course the same problems present. If interviewing schedules are used, then the results will depend on the definition of the universe of behaviour to be studied, i.e., which drugs are to be included, how were they obtained and how were they taken?' It also depends on the ability to get subjects to accept guarantees of confidentiality. Whilst some subjects may be unwilling to recall or report the more 'unpleasant' deviant acts, such as introducing drugs to non-drug users, others will speak quite openly. The third problem, that of obtaining reliable information about the drug users, poses another difficulty. Information is reliable when repeated attempts made on the same respondents by the same measuring instrument would get the same result. Almost all social research eventually has to face the problem of reliability and interpretation of what constitutes drug abuse make it a particularly pertinent problem here. One technique has been to use a battery of screening methods to bring out information from varying sources, but as yet this approach has not demonstrated that it can test reliability, or even validity for that matter, which in this particular context amount to much the same thing.2

Partly because of these difficulties, there are as yet few epidemiological studies on the extent of drug abuse in Britain. A few have been attempted to try to show prevalence and incidence, but the remainder have used the 'informed guess' method. In one study in Crawley in 1967, 50 confirmed heroin users were contacted in the 15-20 age group, giving a prevalence rate of 8.50 per 1,000, and a rate of 14.75 per 1,000 if only males were considered." The numbers known to the Home Office at that time were 8, which would give a rate of 1.4 per 1,000. In 1968 the Addiction Research Unit of the Institute of Psychiatry in a study in a provincial town, found 31 confirmed heroin users, "six of whom were unknown to any of the authorities.'" The method used was to attempt to contact or gain information on all users in that town, and although by no means rigorous the results suggest that there was a considerable degree of "hidden addiction."5 Both studies, however, show that the 'hidden' addicts were young male heroin users, and in this sense point in the same direction as the Home Office figures. This is not of course conclusive evidence that all hidden addicts are in this group as the methods used were to first contact young male addicts and it is likely that their friends or associates would be of similar age.

Accurate data on the more casual user of heroin and cocaine or of drugs such as cannabis or amphetamines, are even more difficult to come by. The most comprehensive study by Dr. R. S. Weiner, using an interview schedule on a sample of 1,093 school children, found that up to 10% had taken drugs." There has been no other study for the older age group. Weiner's study included a large range of drugs; others have concentrated on one drug only. The Office of Health Economics quotes a study which used a questionnaire to a small sample of Oxford students, and the results suggested that 500 out of 10,000 students had smoked cannabis.7 No details were given as to whether this was regular or occasional use. A study at London University found that 4% of the students were currently using cannabis, while about 10% had smoked it at some time.8 Bewley in 1966 suggested that if convictions for cannabis represent only 10% of the users this would lead to a rate of 300 users per million of the population.9

Equally, little is known of the extent of use of other drugs, such as amphetamines or barbiturates. A survey in Newcastle suggested that 500 people from a population of 250,000 were dependent on amphetamines, which if applied to the urban population of Britain would mean 23,000.1" Bewley however has argued that the figure might be as high as 80,000. As far as barbiturates are concerned, over 17 million prescriptions were issued in England and Wales in 1965 and 10 million were issued in the first 6 months of 1966." Schofield reports that over 15 million were issued in 1970.12 He also quotes Glatt who notes that deaths from barbiturates by suicide have risen from 515 in 1956 to 1490 in 1966 and deaths from these drugs by accident have risen in these years from 140 to 525.'3 There have been no studies on the prevalence of use for L.S.D., but Bewley estimates the possible use as 1.5 per 100,000 people."

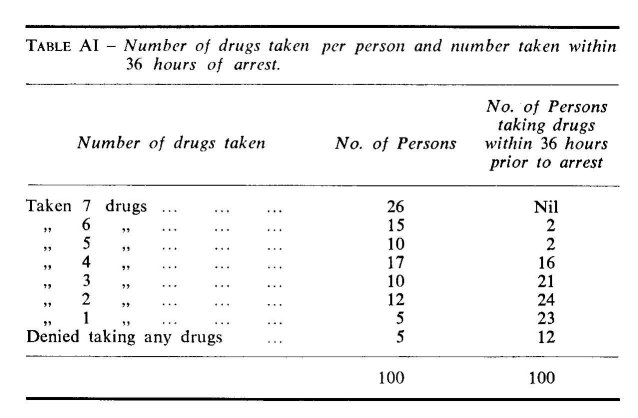

However, simply enumerating the number of persons using each drug will not necessarily give the total number of drug users in the population, as many have used more than one drug at the same time. The Annual Reports for 1969 show that over 1,000 known addicts were receiving two or more drugs and in 1968 there were over 800. These, of course, only refer to licit supplies; Dr. Ian James has referred to Britain as having a polydrug problem where wide ranges of drugs are used. This point can be illustrated in Table AI which is taken from a research study of 100 drug offenders convicted at 2 Central London Courts.15

It will be seen from this table that 68% had taken 4 or more drugs at some time and 20% had taken 4 or more in the previous 36 hours prior to arrest. The schedules which were used to gather the data were restricted to 7 drugs, but some offenders admitted taking other drugs which had not been included on the schedule, e.g., mescaline and opium, and some of these within the previous 36 hours. Other studies have noted similar findings. Hawks suggests that as large numbers of those designated as drug addicts are polydrug users anyway, their designation as being narcotic-dependent or barbiturate-dependent is therefore bound to be somewhat arbitrary."

Equally, little is known about the areas of Britain which produce the largest numbers of 'drug users'. The Home Office figures show that 80% of known addicts are in treatment in the London area and the Home Counties, and the treatment centres were planned with this in mind. By contrast, on 1.1.69 there were only 33 addicts in Scotland, 17 of whom were addicted to heroin. This does not of course mean that all became addicted whilst in London; it may mean that addicts came to London af ter they were addicted because of the better treatment facilities, or because they wanted the anonymity that London provides. It is not known which parts of London have a higher incidence, but it is thought the most likely areas are Piccadilly Circus, Notting Hill, Hammersmith and the East End.

Outside London there have been reports of groups of drug takers in New Towns such as Welwyn Garden City or Crawley, but relatively fewer reports for larger cities such as Manchester, Birmingham or Bristol (e.g. only 11 convictions under the Dangerous Drugs Acts were recorded in Bristol for the 3 years ending 31.12.62). There are no obvious reasons for these varia-tions; the distance from London may be important', but other towns nearer to London, e.g., Luton or Bedford, also report few drug takers.

Much more complex is the relationship between drug taking and crime. The crime figures for the 1930s seem to suggest that drug takers then were not given to much criminal activity; the question is were those in the 1960s more criminal? I am, of course, referring to those who were defined as criminal, mainly the younger drug takers who are, as far as is known, the group most likely to be labelled. The whole area of drug taking and crime is a complex one which is likely to receive considerable attention over the next few years. I shall not attempt to go into the wider theoretical issues, but rather locate the argument in terms of assessing the available research. This I think provides a background to the complexity of the issues and also illustrates the lack of information in this area.

The first difficulty is that most research workers have never been clear about the relationship they are examining. Does drug taking for example 'cause' other crimes, and if so, in what way? Whatever the answer, the few studies that have been concerned with this question have failed either to clarify the issues or to supply us with very much information.

Prior to 1960 there was hardly any research at all on drug users in Britain, and only one or 2 studies concerned themselves with the relationship between drug taking and crime. One notable exception to this was a study by Norwood East in 1937. Of 4,000 youths admitted to Wormwood Scrubs during the previous 7 years, East found that in 200 of these drunkenness was present in one or more close relatives, giving a rate of 50 per 1,000. The proportion with a family history of drug addiction was only 2.25 per 1,000." By the middle 1960s a small number of studies attempted to examine the relationship more closely. It was noted by Dr. Ian James in 1967/68 that over 200 heroin addicts were remanded in one prison in the London area. This represented over one quarter of all male adult heroin addicts known to the Home Office.18 Urine samples from 972 youths on admission to Ashford Remand Centre between April 1967 and 1968 showed ingestion of amphetamines within the previous 24 hours in 6.9% of the cases,1° and Scott and Willcox in a study of amphetamine use in a London boy's remand home found 18% had taken amphetamines prior to admission.2°

The major difficulty in reviewing these studies is that most investigations have been asking different questions and using different types of drug users. Some have concentrated on heroin addicts, others on varying types of users, whilst others again have simply implied a relationship between drug taking and crime, and left it at that. In some cases a few drug users have appeared in different studies which were being conducted at the same time. In an attempt to clarify as far as possible this relationship, a number of separate questions will be asked which although in no way attempting to be exhaustive, nevertheless cover most of the work that has been done.

The first question is, to what extent is the licit medical supply of drugs related to convictions, or in other words, do many drug users illegally sell or give away their prescribed drugs and involve themselves in what we can call primary drug offences? James notes that many British addicts sell heroin and other drugs obtained on prescription, but he gives no figures to substantiate this. The second Brain Report noted that the increase in addicts resulted from the activities of the overprescribing doctor who created surplus supplies that could be given to other addicts. Although no figures were given, the annual increase in new addicts was sufficient to suggest that unlawful supplying was taking place on a fairly large scale. The Annual Reports however, show that for 1967-1969 a total of 204 persons were convicted for unlawfully supplying manufactured drugs, more than half of those (110) in 1969. This is still a fairly small number compared with the 1715 who were convicted for unlawful possession in this same period, but it could be argued that unlawful possession is a less difficult offence to detect than unlawful supply, and the increase in unlawful possession of drugs merely reflects the extent of unlawful supplying. What we do not know are the details about those who supply drugs; for example, do these drug users differ in any way in terms of age, sex or social class from those who do not supply? Are there any differences between those who lend drugs to other users, which is itself an offence, or those who sell them, which is the same offence but could be seen to be qualitatively different? Some answers to these questions may affect the future system of control.

The second main question relates to what we can call secondary drug offences; it is to what extent are drug takers involved in further crimes as a result of using drugs? This question can be examined in a number of different ways. One approach is to consider the style of life and values of the drug taker and to try to show if these have changed as a result of taking drugs. Such changes in values could of course take place for many different reasons, one of which could be as a result of the economic position in which drug takers find themselves after a period of time. James in his study reports that most of his population were "full time addicts whose daily routine was involved in scoring and fixing, and this allowed little time for anything but occasional work." In this sense they had no regular full time employment or earned income, but no details are given as to how they lived.2'

More recently Stimson and Ogbourne reported that 38%. of their population used shoplifting, stealing or selling drugs as a means of support in the month prior to the research interview, and only 22% relied solely on their own earnings. As one of the conditions of receiving Social Security benefits is to establish an address, and as few addicts work regularly enough to pay the rent, the alternative must often be to rely on crime or semi-criminal activities if they are to live. In both of these studies, the addicts' style of life suggests that crime is a necessary means of existence. However, both were concerned with central London populations and the position may not be the same for other drug users, or even for those addicts living out of London. There is some evidence to suggest they are more often living with their parents, and more often in regular work. Another possible reason for a change in values could be that the drug taker has entered a social milieu in which the values are essentially criminal; alternatively he held criminal values before taking drugs and so has merely extended his original value system. It is, of course, extremely difficult to conduct research into these particular areas, and most research workers have been content to ask whether crime increased, decreased or remained the same, without con-centrating on changes in value systems. They have relied on an implication that changes in criminal activity reflect changes in values, although of course they may only be discussing changes in other circumstances such as police activity, and they infer a change towards criminal values simply because the drug taker more often gets prosecuted. However, in a study of 290 boys between 14 and 16 years admitted to Send Detention Centre in 1967, only 3 were convicted on drug charges, but 31 or 12% admitted to having taken drugs.22 In the study of the 972 admissions to Ashford Remand Centre, most of the drug users were charged with non-drug offences. Studies which have not used convicted offenders show a more varied pattern. Bewley and Ben-Arie, in a study of 100 male heroin addicts at Tooting Bec Hospital, found that 75% had convictions for non-drug offences postdating their addiction. The authors point out that these may not be a representative sample of heroin addicts since Tooting Bec Hospital tends to take patients from the Courts, or those who are already ill or have a history of complications. Kosviner et al. showed that only 7 out of 37 heroin takers had been convicted of an offence after drug taking began, but they concluded that their population bore little resemblance to others studied elsewhere, due to the high social class of the drug users' parents. The extra difficulties with these studies are that in examining different types of drug users different value systems may emerge which vary according to the type of drug taken. Perhaps in the circumstances all that one can say is that in some instances—though precisely which are still not known—drug taking may lead to further crime, but more sophisticated ques-tions need to be asked before a less tentative conclusion can be offered.

The final question, which also relates to secondary offences, is to what extent are drug takers "basically criminal"? Schur in 1959 without defining what he meant by "basically criminal" concluded that British addicts differed in this respect from their American counterparts. In this context "basically criminal" meant nothing more than having previous convictions before taking drugs. In a study of 100 drug offenders in the London Courts 39% had a conviction of indictable offences before drug taking began and delinquency prior to drug use was associated with lower social class. Hines in a study of heroin addicts from lower social class origins in the East End of London reported a high incidence of delinquency prior to heroin addiction. The boys had usually embarked on a criminal career in their early teens, and many had been to Approved Schools. Many of the girls were engaged in casual prostitution or were lesbians. Hines felt that his heroin addicts were "basically delinquent" and their addiction was part of the wider problem of juvenile delinquency.23 P. T. D'Orban found, in his study of female addicts, that 60% had convictions prior to becoming addicted to heroin and I. P. James found that 76% of his population also had convictions prior to heroin addiction. But Schofield reports that for all cannabis offenders in 1967 only one-third had convictions of any kind for non-drug offences.24

It seems clear from these studies that between one half and two-thirds of those addicted to heroin can be described as "basically criminal" using the definition of having previous convictions before taking drugs. However, these studies again cover the whole spectrum of drug offences; and some report convictions before taking any drug, others only before taking one particular drug, usually heroin. Some studies draw their samples from prisons, others from the Courts and others from traditionally criminal areas such as the East End of London. It is difficult to come to any conclusions in these circumstances, except to note that more addicts or drug takers had convictions in the 1960s than apparently they had in the 1950s. What is now needed is to relate these factors to others, such as social class. It may for example be that convictions prior to addiction or drug use were correlated with low social class. An interesting feature of some of the studies is that they show an over-representation in Social Classes 1, 2 and 5, but less in Social Class 5 than for other non-drug offenders. In this sense drug offenders appear to differ from the population at large, and from other offenders also. One suggested hypothesis is that drug offenders come from 2 groups, the first being typical working class delinquents and the second typical middle class youngsters who are antecedently less generally delinquent and subsequently slightly more discriminate in their drug taking. Another interest-ing hypothesis comes from a study by Charles Reeves who found that the drug takers in his sample who were labelled as criminal almost always came from Social Class 5. The implication here is that a shift in. the social class distribution automatically means an increase in 'criminals' since traditionally Social Class 5 is the happy hunting ground for police prosecutions.25

From these studies it appears that there is a great deal of evidence to suggest that the legal and medical prescribing of drugs is related to convictions against the Dangerous Drugs Acts, but it is not known to what extent drug taking leads to further crime. However, some heroin addicts, mainly from central London or the East End, appear to be "basically criminal". Further than this we cannot go at this stage except to acknowledge that this is an area from which we cannot expect easy or simple answers. In the U.S.A., where considerable attention has been given to these questions, the results are still inconclusive. Professor Chien argues that the relationship between drug taking and crime is complex, whilst the White House Convention on Narcotics and Drug Abuse in 1962 estimated that property valued at $500 million was stolen each year by addicts in the New York area alone. Harold Finestone sums up the position when he says that "for those holding the view that criminality generally precedes addiction, addiction is regarded as incidental and not a problem separate from criminality. Conversely, those holding that addiction is usually the antecedent event tend to regard criminality as a by-product."26

In a similar vein the Advisory Committee's report on Amphetamines and L.S.D. warns against the use of available research studies from which to draw general conclusions: " . . . it appears to us that all generalisations about the personalities and histories of drug takers and the factors conducive to drug taking must be treated with considerable reserve." Most of the available evidence consists of unsystematic observations and subjective impressions of those drug takers who happen to have come to the notice of doctors, social workers and the Courts, whilst the few scientific surveys that have been undertaken have been restricted in scope." Faced with this obvious lack of reliable data, it appears that, at least as far as research studies are concerned, we must not expect these to give us very much help in this area.

REFERENCES

1. There are many studies on hidden delinquency but see particularly Gibson, H. B. Self Reported Delinquency, and Christie, N. in paper given at the 3rd National Conference on Research and Teaching in Criminology, Cambridge, 1968.

2. de Alarcon, R., personal communication.

3. de Alarcon, R. and Rathod, N. 'Prevalence and Early Detection of Heroin Abuse', Brit. med. J., 1968, 549.

4. Kosviner et al, 'Heroin use in a provincial town' Lancet, 1968, ii, 1189.

5. Yet in 1963 in reply to a question concerning the likely underestima-tion of known addicts, the Secretary of State said that experience showed that when statements are made of underestimation and evidence is sought, very little progress is made in adding to the evidence already known.

6. Weiner, R. S., op. cit., p. 111.

7. Office of Health Economics, op. cit., p. 13.

8. Ibid., p. 13.

9. Bewley, T. H. 'Recent changes in the pattern of drug abuse in the U.K.' Bulletin on Narcotics, Vol. 18 (4), p. 1.

10. Kiloh, L. and Brandan, S. 'Habituation and addiction to amphetamines', Brit. med. I., 1962, ii, 40.

11. Hansard, 1966, Vol. 734, p. 23.

12. Schofield, M. The Strange Case of Pot, Pelican, 1971, p. 23.

13. Ibid, p. 23.

14. Bewley, T. Bulletin on Narcotics, op, cit., p. 1-9.

15. Bean, Philip, op. cit., p. 81. Table AI reprinted by special permission of the Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science, copy-right C 1971 by Northwestern University School of Law, Vol. 62, No. 1.

16. Hawks, D. W. 'The Epidemiology of Drug Dependence in the U.K.' Bulletin on Narcotics, 1970, Vol. 22, No. 3, p. 15.

17. Quoted in Brit. med. J., 1939, ii, 192.

18. James, I. P. 'Heroin Addiction in Britain' British Journal of Crimi-nology, 1969, Vol. 9, op. cit.

19. The Amphetamines and L.S.D., H.M.S.O., op. cit., para. 46.

20. Scott, P. D. and Willcox, D. R. 'Delinquency and the Amphetamines' British Journal of Psychiatry, 1965, iii, 865-875.

21. James, I. P., op. cit., p. 120.

22. Quoted by the Advisory Committee's Report on Amphetamines and L.S.D., op. cit., p. 10.

23. Quoted by James, I. P. and D'Orban, P. T. 'Patterns of Delinquency amongst British Heroin Addicts' Bulletin on Narcotics, June 1970, Vol. 22.

24. Schofield, M. op. cit., p. 52.

25. Reeves, C. University of Southampton, personal communication.

26. Finestone, H. 'Narcotics and Criminality' in O'Donnell, J. and Ball, J. (eds.), op. cit.

| < Prev |

|---|