Chapter Five : THE MAJOR CHANGES SINCE 1945

| Books - The Social Control of Drugs |

Drug Abuse

Chapter Five : THE MAJOR CHANGES SINCE 1945

The first important change occurred in 1959 when an Inter-departmental Committee under the chairmanship of Lord (then Sir Russell) Brain, was appointed with terms of reference "to review in the light of more recent developments the advice given by the Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addic-tion in 1926; to consider whether any revised advice should also cover other drugs liable to produce addiction or be habit form-ing; to consider whether there is a medical need to provide special, including institutional, treatment outside the resources also available for persons addicted to drugs, and to make recom-mendations, including proposals for any administrative measures that may seen expedient to the Minister of Health and the Secre-tary of State for Scotland." 1 Like the Rolleston Committee be-fore it, apart from one pharmacist, all the other members were of the medical profession, although the terms of reference were not exclusively concerned with medical problems.

The background to the appointment of this Committee is still something of a mystery. Neither is it clear what is meant by the phrase, "in the light of more recent developments". What exactly were these "recent developments" that were considered important enough to require the appointment of the first committee for nearly 40 years? One possible explanation is that from 1953 to 1959 there had been an unprecedented increase in known addicts (from 290 to 454, i.e., about 80%) and this was almost entirely due to the emergence of a new group of non-therapeutic, young, male, heroin addicts. In addition, it was also believed that there had been an increase in cannabis smoking and in the use of amphetamines. The "recent developments" therefore were an increase in drug taking which needed a new committee to propose new lines of action.

The official view ignores this theory; this was that by 1959 it was recognised that new synthetic narcotics such as pethidine were being increasingly used by medical practitioners. The main questions which needed special consideration were, firstly, to what extent were these new narcotics able to replace the more traditional opiates as part of medical practice, and secondly, to what extent was the dependency created by these similar to that produced by the opiates. In the official version no mention was made of any increase in drug taking.

There is no information available with which to discount the official view, but it is unlikely that the Home Office could ignore an 80% increase in known addicts. They may well have had one eye on this when the Committee was appointed. They may also have had another eye on the Single Convention which was then almost ready for signature. Taken together, the increase in drug taking plus the activity surrounding the Single Convention, it seemed a particularly appropriate time to make a thorough review of existing procedures and perhaps offer a new approach. But anyone hoping for this new approach was to be sadly dis-appointed. When the Committee reported in 1961 they merely offered a bouquet to the British system and thought that every-one who was concerned with its administration was doing a grand job. They discounted any suggestions that there had been an increase in drug taking in the last few years, and were met with angry critics at the press conference in 1961 when they discussed their report. It so happened that the figures for 1960 had just been released and they showed another increase in the group of young male heroin addicts.

The Brain Committee believed that no new controls were needed as addiction to all dangerous drugs was "still very sinall". They thought that "the figures provided by the Home Office might suggest an extension of addiction", but thought that these reflected "an intensified activity for its detection and recognition over the post-war period." No question seemed to have been asked as to where the so-called newly detected addicts came from in the first place.2 The Committee believed that there was no cause to fear that any increase was occurring at that time, as one of the reasons was that the "professional addict though small in total remains disproportionately high." In fact the percentage of professional addicts, which by then included nurses, was lower than at any other time during the post-war period, and in the 4 years since 1956 it had steadily dropped from 30% to 13%.

The Committee were particularly impressed by what they called "the efficacy of the measures in Great Britain which keep the incidence of drug addiction to such small dimensions." These included the notion that addicts should receive constant medical attention with the doctor responsible for the case having the ultimate decision as to the continued provision of supplies. They believed that the right of doctors to continue supplying drugs to known addicts had not contributed to any increase in the total number of addicts receiving regular supplies. For these reasons the Committee saw no reason to change the system inaugurated by the Rolleston Committee some 35 years previously. They also reiterated the Rolleston Committee's attitudes that addiction should be regarded as an expression of mental disorder rather than a form of criminal behaviour. However, as the numbers of addicts were still seen to be very small, the Committee did not think that it was practicable to establish specialised institutions for the treatment of drug addiction. They thought that treatment could best be undertaken in the psychiatric ward of a general hospital. It was recognised that specialised centres would give medical and nursing staff an opportunity for training and research in the management of addicts, but it was also thought that very few patients would qualify for admission and so they would not be worth the expense.

There may be very good reasons as far as treatment is concerned for not having special "addict centres" unless they provided very special regimes such as Synanon;" however the Committee did not oppose them on these grounds, but because of "the small number of addicts in Britain." The result was that over the next few years there was very little research or information about the treatment of addiction or even of the addicts themselves. H. B. Spear admirably sums up the position—"Once the typical addict ceased to be a middle-aged housewife whose illness was treated, if not understood, with some measure of success by the family doctor; once the known mores of suburbia were exchanged for those of a youthful minority subculture . . . once the comforting solidarity of expert ignorance was exchanged for the frightening limits of a world where each expert's word contra-dicted that of the next, the doctor who ventured into the treatment of addicts had to be unusually brave, compassionate, skillful and lucky if he were to achieve success." 4

In one respect, however, the Brain Committee did change the system. The Rolleston Committee had carefully provided some safeguards against the activities of the overprescribing doctor by introducing the medical tribunals. However, after 1927 when 2 tribunals had already been set up, no further mention was made until 1951 when the Home Office suggested that they should become operative. This suggestion was accepted, and in 1953 a revision of the rules of procedure was taking place when new Regulations were being considered for the 1951 Act. It was decided to postpone temporarily any reference to tribunals in those Regulations, but new ones would be made as soon as possible. But by this time the Franks Committee was already set up with terms of reference to consider the working and constitu-tion of all tribunals and a further postponement was needed until that Committee reported. The Brain Committee in 1959 therefore provided an ideal opportunity to reopen the matter, and their terms of reference included proposals for the recommendation of any administrative measures that might seem expedient.

However, the Committee concluded in paragraph 11 that "after the most careful consideration" tribunals should not be set up in Britain. Their reasons for this were that they did not think there would be a large enough number of irregularities to justify the introduction of further statutory powers and they thought there were too many difficulties to overcome to implement them. "There would be need for powers to take evidence on oath, witnesses who are themselves addicts are notoriously unreliable and it might prove extremely hard to assess sufficient medical grounds in the face possibly of opposing medical opinions." These difficulties are certainly powerful and not to be minimised, but are surely not insurmountable since most of the evidence would simply depend on the number of prescriptions issued and the amounts of drugs on each prescription. There might not be any need to call addicts as witnesses as the prescriptions would speak for themselves. But having recommended that tribunals should not be set up the Brain Committee did not offer any alternative solutions. They also noted that "from time to time there have been doctors who were prepared to issue prescriptions to addicts without providing adequate medical supervision, without making any determined effort at withdrawal and notably without seeking another medical opinion." Having noted this, the Committee's response was merely to state that "such action cannot be too strongly condemned."

Whatever criticisms could have been levelled at the Rolleston Committee there was in a sense a certain logic and thoroughness about their arguments. They may have been over-optimistic about the future, or even tried too hard to please the medical profes-sion, but having taken that stand they at least followed their arguments through to some sort of conclusion. The Brain Com-mittee on the other hand accepted the principles of the Rolleston Committee, noted some of the drawbacks, i.e., over the imple-mentation of tribunals, but studiously avoided adopting the safeguards. They too were optimistic about the future, but unlike the Rolleston Committee had the advantage of government reports on which to base their study. The result was that Britain entered the 1960s with a system which allowed any doctor to prescribe as many dangerous drugs as he wished, justified on the grounds of treatment, but with few legal sanctions or require-ments except to fulfil certain fairly minor conditions such as keeping a register. There were of course the usual ethical standards of the profession as defined by the General Medical Council, but this depended on a complaint being made as to unprofessional conduct and the G.M.C.'s view that overprescrib-ing was contrary to ethical standards. The recommendations of the Brain Committee have not altogether meant the end of the, tribunals as they have at least been reintroduced in the 1970 Act.

After 1960 the increase in known addicts continued. By 1964 the Annual Reports noted that there had been a marked increase in the number of persons addicted to heroin, especially in the younger age group. In 1961 there were 470 known addicts; by 1964 this figure had increased to 753. Predictions were being made that there would be about 11,000 heroin addicts by 1972 if that rate continued, whilst Peter Laurie pointed out that on the Home Office figures there would be about 1 million new addicts in 1984 for that year alone.5 Considerable pressure was placed on the Government to take action, and in July 1964 the Brain Committee was reconvened.° Again, it is not known who were the main initiators of this move, whether it was from Par-liamentary pressure, the Press or even from the Home Office, but the Committee's new terms of reference were to "consider whether, in the light of recent experience, the advice they [the Committee] gave in 1961 in relation to the prescribing of addictive drugs by doctors needs revising, and if so to make recommendations." The Committee interpreted their terms of reference to mean that they should pay particular attention to the part played by medical practitioners in the supply of heroin and cocaine rather than survey the whole field of drug addiction. Pressure from Parliament may have encouraged them to limit their enquiry as it was widely believed that some restraint should be placed on certain medical practitioners who were thought to be taking advantage of the system with N.H.S. and private patients.

After reviewing the position in terms of the increase in known addicts the Committee considered how these addicts had obtained their supplies. After discounting the possibility that "an organised traffic has produced a wave of addiction", they concluded that "the major source of supply has been the activity of a very few doctors who have prescribed excessively for addicts." In what has now become an oft-quoted passage, the Committee were informed that "in 1962 one doctor alone prescribed almost 6 kgms for addicts"—(this incidently was one-sixth of all heroin produced in Britain in 1962)—and that "2 doctors each issued a single prescription for 1,000 tablets (i.e., 10 grammes) [but] these are only the more startling examples. We have heard of other instances of prescriptions for considerable, if less spectacular, quantities of dangerous drugs over a long period of time. Supplies on such a scale can easily provoke a surplus that will attract new recruits to the ranks of addicts."

Although the Committee saw themselves as having a special concern with heroin and cocaine they recognised what they called the dilemma which faces the authorities responsible for the control of all dangerous drugs in this country. On the one hand they thought insufficient control might lead to the spread of addiction as was happening at present. On the other hand, if the restrictions were so severe as to prevent or seriously discourage the addict from obtaining drugs legitimately, he might resort to acquiring these illegitimately, which would lead to the growth of an organised traffic. Their proposals, which they thought would prevent abuse without sacrificing the obvious basic advantages of the present arrangements, were to provide treatment centres for addicts. These they thought would restrict supplies and provide advice where there was some doubt about whether a person was in fact addicted. The Committee also proposed that there should be a system of notification of addicts, a proposal which even the Rolleston Committee had rejected.

The first 2 proposals can be linked. The establishment of treat-ment centres was a radical departure from the precepts laid down by the Rolleston Committee. These centres were expected to be located in part of a psychiatric hospital and it was recom-mended that all Regional Hospital Boards should make suitable provisions. The prescribing, administering and supply of heroin and cocaine would be confined to the doctors in the treatment centres who would determine the course of treatment and if necessary provide the addict with drugs. These proposals, which applied to National Health Service and private patients alike, were to be restricted to heroin and cocaine. It was thought to be impracticable to limit the supply of other narcotic drugs to treatment centres as they were extensively used in the treatment of organic diseases. Such a limitation was thought to be unjusti-fied in the circumstances. But, for the first time in the history of medicine in Britain, most doctors lost the right to prescribe heroin and cocaine for addicts.

The Committee also recommended that any medical practi-tioner should notify a central authority of any new addicts he treated. This recommendation, which had been rejected by the Rolleston Committee and the first Brain Committee, was at last seen to be of value. The second Brain Committee thought the term 'notification' should be seen in the same light as the duty placed on doctors under the Public Health Act to notify the Medical Officer of Health of patients suffering from certain infectious diseases. They thought "this analogy to addiction apt, for addiction is after all a socially infectious condition and its notification may offer a means for epidemiological assessment and control." The reasoning here was unprovocative and likely to appeal to the medical profession; the difficulty is to explain why it took nearly 50 years to bring it about.

Some critics of the second Brain Report argued that the measures did not restrict supplies enough. They argued that maintenance doses of heroin or cocaine, irrespective of who prescribes them, are no bona fide cure for addiction. The primary aim of all treatment for addiction is abstinence, and to supply maintenance doses is equivalent to supplying an alcoholic with daily supplies of alcohol. As such a position cannot be justified on purely medical grounds, the reasons for prescribing must be social. In this sense they should be recognised as such, and to call the new centres 'treatment centres' was, they considered, dishonest; they should be called maintenance clinics.

Others in similar vein saw the whole process of supplying addicts with dangerous drugs and allowing them to use them at will as medically or morally wrong. They argued that addicts were often unstable, either before, or as a result of their addiction, and to supply them with quantities of dangerous drugs such as heroin was virtually inviting them to give away or sell some of these drugs, thereby always increasing the number of new addicts. Also, to provide the addict with drugs and a syringe and allow him to inject it himself in unhygienic conditions and with no previous training was a danger to his health and to other people's. As addicts were known to meet in such places as Piccadilly Circus underground station and use unsterilised water with their injections, it was inevitable that a high incidence of disease and death would follow.

Other critics saw the move to take away the doctors' right to prescribe heroin and cocaine as a panic measure and a retrograde step. They argued that the Brain Committee had concluded that since only a very few doctors were responsible for excessive prescribing the matter should be dealt with by restricting those few rather than taking away the right to prescribe from all. They also thought the treatment centres would mainly be staffed by junior hospital doctors who might not be particularly interested in these types of patients anyway, nor would it be likely that they would be specialists in this field. This would mean that the addict would not get the full care or attention he required. The G.P., on the other hand, who accepted patients because he wanted them, was likely to be a more permanent figure who could experiment with treatment and not be tied to hospital policy. Furthermore, as he was only prohibited from supplying heroin and cocaine he could still supply other drugs. This would inevit-ably produce some duplication of treatment and would not solve the problem of the doctor who overprescribed any other drugs. This could only be done by the tribunals which the Rolleston Committee proposed, but which both Brain Committees had not thought fit to introduce.

The treatment centres fail to answer either set of criticisms. On the one hand if they concentrate on heroin and cocaine they may simply be making an artificial distinction if overprescribing of other drugs continues unchecked. This incidently occurred with the increased use of methedrine in 1968 and drinamyl in 1969. On the other hand, the treatment centres, by prescribing heroin and cocaine, fail to meet the problem of allowing the addict to have and administer his own drugs.

There is a good deal of evidence to support this view that to allow drug takers to administer their own supplies produces a large number of secondary complications. In a recent report on a sample of addicts who were being prescribed heroin at the London clinics, 37% said they sold, exchanged, or loaned some of the drugs they were prescribed. This study also looked at injection practices in their sample of 111 subjects, and if injection practices are defined as 'sterile' when normal medical procedure is followed, then only 11% were using sterile practices. 49% had at some times during the previous week used ordinary unboiled tap water, and 11% had used water from a lavatory basin. Nine subjects reported sharing a syringe with another addict during that week.8 Another study by Bewley, Ben-Arie and James° examined the death rates of known heroin addicts from 1945-1966. During this period 969 males and 303 females became addicted to heroin, only 35 of whom were therapeutic addicts. Sixty-nine deaths were recorded amongst the non-therapeutic group which meant that 1 in 37 heroin addicts had died since 1947, most deaths being attributed to self administra-tion of drugs or the direct consequences of chronic drug intoxication. Or, put another way, they had a mortality rate 28 times the normal for their age groups. These authors also concluded in another study that to supply addicts with syringes had not reduced the incidence of diseases such as hepatitis caused by dirty needles.'° There does not seem any way of reducing these difficulties, and it may not be advisable anyway if the addict is to continue to be encouraged to seek some form of 'treatment', even if it is only maintenance doses of addictive drugs, but it does illustrate the point that the attempt to achieve a balance is going to produce a compromise of sorts which is still open to criticism. The compromise which the second Brain Committee sought was one between reducing overprescribing but doing this in a way which still encouraged the addict to receive legitimate supplies. The fear of organised crime and the so-called Mafia has been an ever present vision which should allow the addict to feel sufficiently confident that legal supplies will never dry up completely.

Most of the changes proposed by the second Brain Committee Report were accepted by the Government and implemented in the Dangerous Drugs Act, 1967. It is difficult to know why this Act should have taken over 2 years to implement in the light of the Committee's findings about overprescribing. During these 2 years the known addicts increased by more than 100% from the time the Committee reported to the time the Act was operative on 27th October 1967. Some M.P.s agitated for quicker action, arguing that few structural changes were required to introduce the treatment centres or to remove the right of doctors to prescribe heroin or cocaine, but the delay was said to be caused by serious matters involving extensive consultation as "profes-sional interests" were involved»

The 1967 Act, in addition to providing Regulations for the establishment of treatment centres and for G.P.s to be prohibited from supplying heroin and cocaine — (these Regulations inciden-tally came into force on 16th April 1968) — also required all medical practitioners who attend a person and have reasonable grounds to suspect that he is addicted to drugs to furnish such particulars as may be specified to the central authority. These particulars include name, address, sex, date of birth, N.H.S. number, the date of attendance and the name of the relevant drugs. These Regulations came into operation on 22nd February 1968.

Furthermore, under Sections 4 and 6 of the 1967 Act, Regula-tions were made requiring extra precautions for the safe custody of drugs and giving to all police officers further powers of search to obtain evidence. The Act also increased penalties and gave authority to Magistrates Courts to pass heavier sentences. These sections will be discussed in more detail in a later chapter. One recommendation not implemented was the Committee's proposals relating to the compulsory detention of addicts. The Committee thought that the treatment centres should have powers to detain an addict during a crisis in the treatment because of what they called the "obstinacy of some addicts and the likelihood that some will not attend the treatment centres or that others may break off treatment after they have embarked on it." Somewhat understandably this has been widely interpreted as being a recom-mendation for the compulsory detention of all addicts for treat-ment, but it is also clear as C. G. Jeffery says that, "if effect were given to it, the great majority of addicts would shun the proposed treatment centres entirely."12 It also sounded a little like a panic reaction, after the absence of any recommendation for change in the previous report.

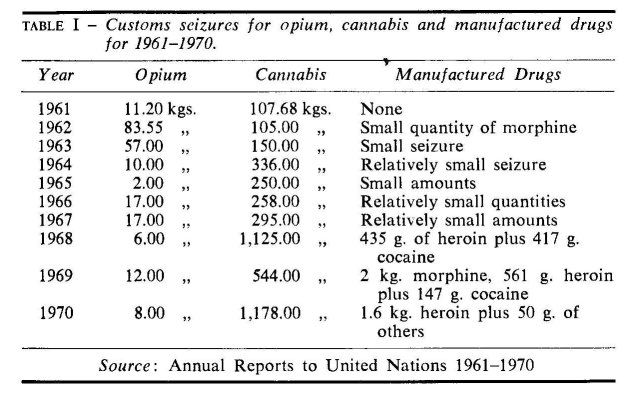

The effect of the 1967 Act is not yet fully understood. It was expected to bring to notice large numbers of new addicts who had previously become and remained addicted from illicit supplies. When the treatment centres began to reduce the overprescribing, these addicts would then be forced to attend the centres for further supplies and thereby be notified to the Home Office. This largely happened, and the number of new addicts for 1968 was a record 1,476, giving a net increase of over 1,000. But after 1968 the curve of known addicts began to level off and the 1969 figures showed a net increase of only 99, or 3.5% compared with 50% for the preceding year. The number of new addicts also dropped to 1,030. These figures have led the Home Office to state in their Annual Report for 1969 that they are "cautiously optimistic", although it is too soon to know how much this may be an artefact created by the 1967 Act. A similar trend occurred in 1970 and the same note of cautious optimism was given. Whether this means a reduction in addiction or a reduction in known addicts is still not clear, but some authorities argue that the treatment centres have been too strict about supplies and the addicts are now turning to illegally imported heroin. There is some evidence to support this view, and Table I lists the customs seizures of some drugs for the period 1961-1970. Notice how 1968 was the first year when large quantities of morphine and heroin were seized.

It was not until 1968 that precise quantities of customs seizures were recorded for manufactured drugs. Prior to that the reports usually noted that 'small quantities' were seized. After 1968 there appears to have been an increase in customs seizure — that is if we assume that these quantities were greater than the previous 'relatively small amounts' so that by 1970 the seizures for heroin had risen to 1.6 kg. It is this type of evidence which supports the view that the treatment centres were being too cautious in prescribing heroin, thereby diverting the addicts to the illicit traffic.

It is interesting to note that customs seizures for cannabis and opium have fluctuated widely in the last 10 years, though it is impossible to say how much these figures reflect fluctuations in the use of cannabis or opium." The reports always stated that trafficking did not exist on any organised scale, but this of course depends on what is meant by 'organised'. But an Advisory Committee set up after the 2nd Brain Report noted that "recently a more sinister element seems to have appeared." They were informed by the police that one team of professional criminals were believed to be organising the purchase, sale and transport of drugs via London, France and Ireland, whilst a second team had been running drugs from the Farnham area to Portsmouth.

So far changes in control of the more 'traditional' drugs controlled by the Dangerous Drugs Act have been discussed. However, after World War II other substances became defined as drugs, some of which produced addiction, others psychological dependency whilst others did not appear to produce either. Some of these new drugs are taken orally, others injected and others again are used either way. By 1970 the range was so wide as to defy any attempt at classification, and it was then that the World Health Organisation stated that "It must be empha-sised that risk to public health is the prime determining factor in deciding for or against control of a particular type of drug."

In 1954 the amphetamines were controlled by the Pharmacy and Poisons Act. Possession of these drugs was nöt an offence unless it could be proved that they had been sold contrary to the provisions of the Act, and supply other than by a sale was no offence. The police were not able to take action against suspected traffickers in amphetamines unless a cash transaction could be proved.

It is not altogether clear if the Pharmacy and Poisons Act was designed to control amphetamines in the first place. In 1933, in the Parliamentary debates on the Act, it was said to be designed "to assist in inspecting, organising and making regulations for proper sale and supply of medicine and drugs in a way that would be safe to the public."14 Barbiturates were to be included "because of the alleged increase in fatalities due to the use of these drugs", but by this criterion it is doubtful if amphetamines would qualify. However, Parliamentary pressure 15 in the 1960s began to demand more restrictive measures than were given by the Pharmacy and Poisons Act — perhaps as a result of a series of articles by Anne Sharpley in the Evening Standard where she drew attention to the increased use of amphetamines by teenagers in Soho. In 1964 the Drugs (Prevention of Misuse) Act was passed applying to amphetamines and related drugs such as phen-metrazine (preludin). It created the offence of unauthorised possession of these drugs, and offences against this Act were punishable on summary conviction by a fine not exceeding £200 or imprisonment not exceeding 6 months or both, and on indict-ment by an unlimited fine or by imprisonment not exceeding 2 years or both. The Act prohibited imports of the drug except under licence. The Act itself was a radical departure from previous legislation as for the first time it controlled drugs not related to international treaties. During the debate in the House of Commons, one member noted this change in principle, but it was not taken up, so keen was the House to introduce fresh legislation. One Member even wanted the provisions to apply to local authorities having control over coffee bars.

However, as C. G. Jeffery points out, "While these new measures had the intended effect of enabling the police to prefer a charge against anyone found in unauthorised possession . . . it soon became apparent that it was defective in a number of ways, the most important being the absence of any provisions relating to security of storage on the premises of manufacturers."1° The 1967 Dangerous Drugs Bill was amended to include security and storage of drugs under the 1964 Act.

One other feature of this Act is that it provided machinery for bringing substances other than amphetamines under control, but it did not have any provisions for the effective control of their distribution. By 1965 there was evidence of the increasing use of L.S.D. and other hallucinogenic drugs such as mescaline and psilocybin. These were later controlled in 1966 under the Drugs (Prevention of Misuse) Act by a Modification Order. At about the same time there was a rapid increase in the prescribing of methylamphetamine (methedrine) which was being used with heroin and often preferred to cocaine. When the Supply to Addicts Regulations under the 1967 Act became operative, some doctors who were no longer allowed to prescribe heroin or cocaine continued to supply methedrine. As there was no way of preventing this under existing legislation, a purely voluntary agreement was reached in October 1968 between the pharma-ceutical manufacturers and the medical profession that methe-drine should only be supplied to hospital pharmacists or in strictly limited quantities to medical practitioners. This move was given complete support by the British Medical Association.

By 1970 the varieties of both drugs and Acts required more comprehensive and consolidating legislation. The Misuse of Drugs Bill was presented to Parliament on I 1 th March 1970 and had its second reading on the 25th March. The Bill lapsed with the change of government, but was reintroduced in almost exactly the same form and had the second reading under the Conservative Government on the 16th July 1970. It came into operation in 1972.

The Misuse of Drugs Act replaced all previous Acts. It was considered to be a piece of "machinery for consolidating legis-lation", and the Home Secretaries of both Governments stressed the deficiencies of the previous legislation which they thought was either too inflexible to cope with the changing patterns of drug use, or in some cases simply inadequate. In addition, previous Acts had preserved an artificial distinction between narcotics and other drugs which was now thought to be outmoded. The old Acts were also inflexible because they automatically gave the right to all authorised personnel to supply any new drugs that were listed on the schedules whether this was necessary or not.

The Conservative Home Secretary saw the Bill as having 4 main aims. The first was to distinguish between possessing drugs and trafficking; the second was to have power to operate without consulting international bodies, so that by an Order in Council new drugs could quickly be brought under control. The third aim was to stamp out overprescribing which was to be achieved by banning doctors from prescribing specific drugs, if it could be established that they had been prescribing irresponsibly. Finally the Home Secretary was to have a Council to advise on policy matters from which he was empowered to demand information about the supply of any new drugs (see Sec. 17).

To achieve these aims, drugs were divided into 3 classes, and the severity of punishment varied with each class. The most important group were the Group A drugs which included almost all the drugs controlled internationally under the Single Conven-tion with the exception of 6 drugs, 2 of which were cannabis and cannabis resin, which together with other important central nervous system stimulants came into Group B. Group C contained the least serious, which were the less potent C.N.S. stimulants. The maximum penalties on indictment for possessing drugs in Group A is 7 years imprisonment, for Group B 5 years, and for Group C 2 years.

The effect of this new classification has been to increase the penalties for some drugs and decrease them for others. For example, for possessing L.S.D. the penalties have increased from 2 years to 7 years imprisonment and for possessing amphetamines from 2 years to 5 years. For possessing heroin penalties have decreased from 10 years to 7 years imprisonment and for possess-ing cannabis from 10 years to 5 years.

A distinction is made in the Act between possessing and trafficking, the latter being defined as "possession with intent to supply unlawfully". For those convicted under this section there are special penalties related to the drugs in the three groups. For example, a conviction for trafficking Group A drugs carries a maximum sentence of a fine or 14 years imprisonment or both, compared with 7 years imprisonment for possessing drugs in that group.

The third major change in the Act is that the Government have at last introduced the tribunal system. Some consideration will be given in Part II to the general problem of sanctions for over-prescribing, but at this stage it is only necessary to note that these tribunals will have the power to remove the right to prescribe certain drugs, and that the maximum penalty for continuing to prescribe under these circumstances in the case of, say, a Class A drug, is a fine or 14 years imprisonment, or both.

When the Bill was before Parliament it was, generally speaking, greeted with signs of approval. Some critics however pointed out certain anomalies, some of which have existed since the first Act was passed in 1920. One amendment asked the House to reject the Bill because "it omits any reference to the most dangerous drug currently available, namely tobacco . . . [even though] some 75,000 deaths occur a year as a result of smoking."" Other critics wanted to know why barbiturates were not included. The reply from the Labour Home Secretary was that the schedules under the Act were aimed at "maintaining the present lists" and that widespread use of drugs such as barbiturates made effective prevention very difficult to achieve. This is a curious argument to say the least; cannabis has widespread use, but this did not stop Governments or even the League of Nations from including it on their prohibited list.

There was a considerable amount of criticism at the Govern-ment's decision to classify cannabis as a Group B drug with maximum penalties of 5 years imprisonment for possessing it. Few Members seemed to want to legalise it altogether, but one suggested it could be listed in a class of its own with severely reduced penalties. His reasons for this were the lack of unanimity as to its harmfulness, and the fact that it involved too many social and political judgements. Another Member believed there were worse dangers to society than taking drugs; one was the deepening antagonism between the police and certain groups of young people which could soon lead to the point where the latter had no respect for the police. In spite of these criticisms, cannabis remained a Class B drug, a tribute perhaps to fears about the validity of the escalation argument that cannabis leads to heroin addiction. It was also perhaps a tribute to the political implica-tions of a government being labelled permissive.

There were few criticisms about 2 other sections in the Act, both of which seem highly contentious. One section retained the police power of arrest and search which had been introduced in the 1967 Act. The other was the distinction made in the Act between possessing drugs and trafficking. It is doubtful if such a distinction has much value, either as an analytical tool, or as a deterrent argument, and Baroness Wootton also doubted if professional racketeers calculated that it may have been worth trafficking in drugs when the penalties were 10 years imprison-ment, but the extra 4 years would be just that bit too much. She did not think the issue was as simple as this. The arguments employed to support the possession/trafficking distinction were a mixture of deterrence and "emphatic denunciation of the crime" type of approach. The latter of course fits in well with a view of drug taking which sees the 'pusher' as the main villian in the piece. It may well be a simplistic approach, but it allows a certain sympathy for the addict and retains the righteous indignation for the pusher who 'enslaved' him or first peddled him his drugs. It is a view remarkably similar to the American philosophy which sees the problem as being somewhere else; either in the Turkish poppy fields or the French heroin factories. Parliament is cer-tainly right to concern itself with trafficking, but the new Act, if it is radically to alter the course of events, can only be based on a triumph of hope over experience. Yet as long as there are demands for drugs within Britain coupled with restrictions on supply, there will inevitably be trafficking. Herbert Packer puts the point forcibly in relation to the U.S.A. "Regardless of what we think we are trying to do, if we make it illegal to traffic in commodities for which there is an inelastic demand, the actual effect is to secure a kind of monopoly profit to the entrepreneur who is willing to break the law."'s Total prohibition of drugs in the U.S.A. may have decreased the number of narcotic addicts if Commissioner Anslinger is to be believed, but at the cost of a lucrative illicit traffic and criminal drug subculture. No one has seriously considered that Britain should adopt the American system whose defects are much too obvious to be overlooked. In the last resort the extent of the illicit traffic will be determined by such factors as legitimate availability and societal reaction to the drug user. Following Lindesmith it is more relevant to see the problem as being within Britain than just to blame the illicit importer and the countries named in the Annual Reports from whence the illicit drugs came. The then Home Secretary, Mr. Callaghan, claimed to have discussed some of his ideas with a group of drug takers who, he said, had been firmly convinced that he should not legalise cannabis. During the Parliamentary debate on the 1970 Bill it was reported that a B.B.C. T.V. team interviewed a group of drug takers in Piccadilly Circus and asked them about the likely effects of the Act. None of them thought it would make the slightest difference. In one sense they were right — there are limits to what the law can do. The difficult question is to assess the extent of its influence, both for good and ill.

REFERENCES

1. Interdepartmental Committee on Drug Addiction, H.M.S.O., 1961, para. 1.

2. See also Jeffery, C. G. Drug Control in the U.K., Phillipson, op. cit., p. 69.

3. See Yablonsky, L. The Tunnel Back; Penguin, 1967.

4. Spear, H. B., 'Dangerous Drugs Legislation 1967', in Police Journal, June 1968.

5. Quoted in Drug Addiction, 0.H.E., 1967, p. 9.

6. The only changes in the membership of the reconvened Committee were Dr. Henry Matthew and Dr. A. J. Pikheathly in place of Sir Derrick Dunlop and Dr. A. H. Macklin.

7. Drug Addiction, the Second Report of the Interdepartmental Com-mittee, H.M.S.O., 1967.

8. Stimson, G. V. and Ogbourne, A. C. 'A survey of a representative sample of addicts prescribed heroin at London clinics', Bulletin on Narcotics, Vol. XX, No. 4, p. 17.

9. Bewley, T., Ben-Arie and James, I. P., 'Morbidity and Mortality from Heroin Dependence', Brit. med. J., 1968, i, 725.

10. Bewley, T., Ben-Arie and Marks, V., 'Relations of Hepatitis to Self Injection Techniques', Brit. med. J., 1968, i. 730.

11. Hansard, 1966, Vol. 728, p. 10.

12. Jeffery, C. G. op. cit., p. 72.

13. The reports for 1970 stated that " traffickers [in cannabis] used many ingenious methods of concealment . . . the parcel post was extensively used . . . the device of hollowed out books being frequently en-countered".

14. At 3rd reading of the Bill in 1933, see Parliamentary Reports for 1933, and Report on the Departmental Committee in 1930.

15. See Parliamentary Reports for December 1959 and February and March, 1960.

16. Jeffery, C. G. op. cit., p. 73.

17. Hansard, 16.3.70.

18. Packer, H. L., 'The Crime Tariff' in The American Scholar, Vol. 33, 1964, p. 551-557, quoted by Skolnick, J. H. in Justice without Trial, John Wiley and Sons, 1967, p. 207.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|