THE ETHNOLOGY OF PEYOTISM

| Books - The Peyote Cult |

Drug Abuse

THE ETHNOLOGY OF PEYOTISM

NON-RITUAL USES OF PEYOTE

An Oto in all seriousness informed the writer that "peyote doesn't work outside meetings, because I have tried it"—a belief understandable in a group whose sole acquaintance with the plant is through a recent ritual.'1 Nevertheless, owing to its marked physiological properties peyote is widely used both in Mexico and the Plains non-ritually, a fact which forms an interesting ethnological background to the rite proper.

One of the most important and striking of these uses is in prophecy and divination. We find the Spanish missionaries in Mexico early protesting against this abomination. The confessional of Padre Nicolás de Leon 2 contains the following questions for the priest to ask the penitent:

Art thou a sooth-sayer? Dost thou foretell events by reading omens, interpreting dreams, or by tracing circles and figures on water? Dost thou garnish with flower garlands the places where idols are kept? Dost thou suck the blood of others? Dost thou wander about at night, calling upon demons to help thee? Hast thou drunk peyotl, or given it to others to drink, in order to discover secrets, or to discover where stolen or lost articles were?

This last was no idle matter, as appears from other evidence; Hernandez' 3 says that

[the Peyotl Zacatensis] causes those [Chichimeca] devouring it to be able to foresee and to predict things; such, for instance, as whether on the following day the enemy will make an attack upon them; or whether the weather will continue favorable; or to discern who has stolen from them some utensil or anything else; and other things of like nature which the Chichimeca really believe they have found out.

Padre Arlegui,4 after mentioning the therapeutic uses to which the Zacatecans put peyote, complains that

this would not be 80 bad if they did not abuse its virtues, for, in order to have a knowledge of the future and find out how their battles will turn out, they drink it brewed in water, and, as it is very strong, it intoxicates them with a paroxysm of madness, and all the fantastic hallucinations that come over them with this horrible drink they seize upon as omens of the future, imagining that the root has revealed to them their future.

Prieto' says of a Tamaulipecan group that

often in these orgies was wont to impose silence, at the height of their drunkeness, the voice of some ancient, who, assuming a magisterial tone, prognosticated to them future events, usually depicting them as sad and unhappy, and in spite of the lugubriousness of his predictions, he usually ended his harangue by exhorting them to enjoy in the dance the interval between the present and the next unhappiness.

Alarcon6 adds other functions and relates of other drinks similarly used :7

If the consultation is about a lost or stolen article or concerning a woman who has absented her self from her husband, or some similar thing, here enters the gift of false prophecy, and the divining that has been pointed out in the preceding treatises; the divination is made in one of two ways, either by means of a trance or by drinking peyote or ololiuhqui or tobacco to attain this end, or commanding that another drink it, and ordering him to remain under its spell; and in all this goes implicitly hand in hand the pact with the devil who by means of said drinks appears to them and speaks to them, giving them to understand that he who speaks to them is the ololiuhqui or the peyote or whatever beverage that they had drunk for the said end; and the sorry part of it is that many put faith in [the drink] as in the very lying cheats themselves, [indeed] even more than in the evangelical predicators.

As we move farther north in Mexico the use of peyote in prophesying becomes valuable in warning of the approach of the enemy.8 For the Tarahumari Lumholte says that the various kinds of hikori were particularly good "to drive off wizards, robbers, and Apaches, and to ward off disease." Of Anhalonium fissuratum he says "robbers are powerless against it, for Sutlami calls soldiers to its aid," while the variety Rosapara "is particularly effective in frightening off Apaches and robbers."

In the Comanche version of the usual Plains origin tale of peyote, the leader of a group on the warpath goes up alone to an Apache camp where a peyote ceremony is in progress. Though an enemy, he is invited in, the leader telling him that peyote had predicted his coming in a vision.10 One Comanche informant said eating peyote enables one to hear an enemy coming, though still far away; peyote likewise predicted the success of one of the last Comanche horse-raids, and aided in its prosecution.

From these uses of peyote in war it is no jump to its fetishistic use as a protector in war 11 and in ordinary witchcraft. Sahagun 12 writes that peyote is a common food of the Chichimecas, for it stimulates them and gives them sufficient spirit to fight and have neither fear, thirst, nor hunger, and they say it guards them from all danger.

De la Serna"13 said that ololiuhqui and peyote were carried by persons "forsaken of God" as charms against all injuries, and Arlegui deplored the custom of parents to "hang little bags on their children, and inside of them in place of the four Evangels that they place around the necks of children in Spain, [to] place peyot or some other herb." Arias described a surreptitious worship of the fetish: the natives hung the herb in the choirs "as a special creation of the malignant spirit which they designate with the name of Naycuric," and they communicated with the numen by drinking an infusion of peyote instead of wine."14

Peyote is also a powerful protection against witchcraft in ritual foot-races. Rivals are liable to throw bones and herbs on the track and cause the Tarahumari runner to be bewitched and lose the race, which is run at night. For this contingency, however, "hikuli and the dried head of an eagle or a crow may be worn under the girdle as a protection."15 Peyote is a great protection too when traveling, both in war and on peyote-pilgrimages."16

The Comanche commonly wore peyotes in buckskin bags attached to beaded bandoliers, recalling the mescal bean bandolier which the Kiowa and others commonly wore in battle. Indeed, peyote was even a part of the Oawikila and Kispoko war bundles of the Shawnee, long before they knew the generalized peyote ritual—a custom similar to the Iowa use of mescal beans in their war bundles."17

But in Mexico and the Southwest war and witching are closely connected ideologically. As a matter of fact, peyote itself as well as the peyote shaman's rasp, is employed in Tarahumari witchcraft." 18 Among the Mescalero Apache," 19 however, witching within the tribe by rival peyote shamans was an ever-present anxiety, their feuds being conceived in terms of battles and war, with the "shooting" of arrows and struggles to see who had the more powerful and compelling songs. The Mescalero peyote leader was merely a shaman primus inter pares, whose major function was to prevent witching in meetings. The purpose of the Tonkawa peyote songs, it is said, was to ward off the enemies' witching. Witching with peyote is less in evidence in the Plains, save among the Kiowa, Comanche, and Cheyenne who early received it, but as late as the time when the Caddo-Delaware messiah John Wilson took peyote and the Ghost Dance to the Quapaw there was witching by "shooting" objects. The Northern Cheyenne feared the "trickiness" of peyote itself; and the Lipan fireman was chosen for his braveness because "he has to go out at night to get wood and it is a frightening job sometimes, especially when one is under the influence of peyote; peyote is sure a joker!"

Besides this fetishistic use in war, peyote was also used somewhat more "technologically" to cure wounds. Alegre writes that the Sonoran

manner of curing the wounds is with peyote, that they call peyori after it has been made into a powder, with which they fill the cut, cleaning it and renewing it three times every two days, or with a species of balm composed of [maguey].

Prieto says that, in Tamaulipecan war, among the provisions carried by the women in the rear were gourds full of peyote and water . . . and in addition to all these provisions they carry some plants, which, chosen and prepared beforehand serve to stop hemorrhages from the wounds, and to aid in their curing.

The Opata used pejori for arrow-wounds, cleaning them out with cotton squills on sticks dipped in the powder; the Lipan put peyote on wounds of all kinds."20

The other therapeutic uses of peyote are various. At Taos it was used for snake-bite. The Caxcanes of Teocaltiche employed peyote for cramps and fainting spells, the Chichimeca for relieving painful joints. The Tarahumari apply peyote externally for bruises, snake-bites and rheumatism. The Huichol use few remedies except hikuli, unlike the Tepecano who use many, but it is good for anything from a minor ache to a major wound. Medicinal uses are also recorded for the Tepecano, Yaqui, Opata, Pima, Papago, Cora and Lipan."21

In the Plains a Wichita case of blindness of fifteen years' standing was cured by the sole application of peyote-infusion." Radin cites a similar Winnebago case. The Kiowa use peyote as a panacea: uses are recorded for tooth-ache, hemorrhages, head-ache, consumption, fever, breast pains, skin disease, hiccough, rheumatism, childbirth, diabetes, colds and pulmonary diseases in general. Mooney records the further use as a "tonic aperitif." The Shawnee chew peyote into poultices for sores and snake-bites and eat it for colds, pneumonia, rheumatism, aches and pains."23

The remaining non-ritual uses of peyote are quite varied. The Acaxee employed it in some manner in their ball games, probably eating it in small doses, according to Beals. In Tlaxcala peyote was used by "the auxiliary forces of the conquistadores, in order not to feel fatigue on their marches"—a widespread use in Mexico; in the Plains the typical origin legend tells of peyote aiding a seriously wounded warrior or a woman and child left behind by their companions without food or drink. The legend is not unlike the common Plains stories of receiving power from animals in a stress-situation; Old Man Horse (Kiowa) said "peyote is the only plant from which one can get power," obviously thinking in terms of the old vision quest. Peyote in fact gave power to perform shamanistic tricks in the old days."24

The Tarahumari, among other things, left a hikuli plant with the corpse, the motive for which is unstated." A Wichita, captured in war and imprisoned, was aided in escaping unseen from the enemy camp by his fetish-plant; the lobbying power of peyote in influencing Federal bonus legislation has already been mentioned. Indeed, peyote has had a record of unbroken success in preventing Federal anti-peyote legislation."25

RITUAL USES OF PEYOTE

Despite the unsatisfactory state of the literature, it is clear that the ceremonial use of peyote in Mexico differs widely from that in the Plains. First we shall characterize the Mexican type by summarizing the Huichol and Tarahumari rites, and later adding comparative Mexican data.

HUICHOL

Though the most important of their fiestas, Huichol peyotism is a seasonal matter, the hikuli seldom being eaten outside the ceremonial period in January. In October a preliminary trip lasting fifteen days each way is made to Real Catorce (San Luis Potosi) to obtain the plants. The eight or twelve pilgrims bathe and sleep in the temple with their wives the night before leaving, not washing again until the feast some four months later. After receiving new names for the trip, the next morning they pray around a fire, wearing squirrel tails tied to their hats, and sacrifice five tortillas"27 to the fire. Then, after sprinkling their heads with a deer-tail dipped in water steeped with certain herbs, all weep as each man puts his right hand on his wife's left shoulder and bids her farewell."28

Their route is full of religious associations, since formerly the gods went out to seek peyote and now are met with in the shape of mountains, stones and springs; their dreams en route are also important in deciding religious arrangements for the coming year (who is to sacrifice cattle for rain, who is to be fire-maker, etc.). The pilgrims carry sacred hourglass shaped gourds and the leader also carries the yákwai, a ball of native-grown tobacco called macuchi, which is solemnly distributed after they pass Puerta de Cerda. In the afternoon they place ceremonial arrows toward the four corners of the world, and sit around a fire until midnight. Tobacco belongs to the personified fire; after much praying the leader touches the tobacco-ball with his plumes and wraps small portions in corn husks"29 "so that they look like diminutive tamales,"30 and each man puts one in a special tobacco-gourd tied to his quiver. This act symbolizes the birth of tobacco and henceforth they must preserve ritual order on the march, and only cease to be the "prisoner" of Grandfather Fire when the sacred bundles are given back to him, i.e., burned.

On the fourth afternoon the women at home gather to confess their sins to Grandfather Fire; they knot palm-leaves lest they forget the name of even a single lover and the men consequently find no hikuli. After this public confession each woman throws her leaf into the fire and becomes ritually clean. The men make a similar confession "to the five winds" a little beyond Zacatecas and burn their tallies in the fire. The hikuli-seekers are henceforth gods and the leaders fast (save for eating stray plants) until they reach the peyote country.30

Arrived, they line up, each man with an arrow on his bow-string which he points successively to the six regions of the world without letting it fly. As they march toward the mesa-"altar" where the leader has seen hikuli as a "deer," each man shoots two arrows each over five hikuli plants, crossing over their tops that they may be taken "alive." They make a ceremonial circuit of the mesa, but the "deer" assumes the form of a whirlwind and disappears, leaving two hikuli in his tracks; there they sacrifice votive bowls, arrows, paper flowers, beads, etc., and pray. After this they return to get their five hikuli, and eat and gather others. The whole ceremony is of hunting deer, and after five days they reverse the logs of their fireplace and return home with gourds of holy water, wood for the shaman's rasp, sotol for the "godseats," yellow paint material and the hikuli they have gathered. Their tobacco-gourds and faces are painted yellow, the color of the God of Fire. The face-painting represents the faces or masks of the gods, and expresses prayers for rain, luck in deer-hunting and good crops, symbolized as corn field, cloud, ear of corn, "rain-serpent," squash-vine and -flower designs."31

Approaching home, they must hunt deer until they have enough for the feast, before being freed from the ritual restrictions of continence, fasting, and non-use of salt, meanwhile being sustained by slices of green hikuli eaten from time to time. The deer meat is cooked and then cut into small cubes which are strung (precisely as peyote is) on cords." 32 The deer-killing is to obtain rain for the next growing season." 33 The hunting period over, men and women bathe for the first time since the beginning of the hikuli-pilgrimage.

For the hikuli feast the men deck their hats lavishly with brilliant macao and hawk feathers, and wear supernumerary girdle-pouches; the women wear strings of yellow and red plumes across the back. A temple fire, another at the east of the patio to "guard" the dancers, and a third at the north for visitors from the underworld are built in a special fashion: the shaman carefully brings an eighteen-inch billet of green wood, offers it to five directions and finally to the sixth by placing it on the ground, after which others place sticks pointing east and west on this molitáli or "pillow" of Grandfather Fire."34

Then the shaman and hikuli-seekers ceremonially circle the freshly white-plastered "god-house of the Sun," enter, pray aloud and give a long account of their journey until late at night. The temple fire place (áro) is a circular clay basin in the center with a slightly raised rim; the poker is the "arrow" of the God of Fire. The niches at the west of the temple behind the shaman are filled with god-images; the others sit on either side of him in a semi-circle on sotol or century-plant stools. Their wives, flower-garlanded and painted, sit farther back in the temple, while the pilgrims smoke and sing all night about Great-grandfather Deer-Tail, the Morning Star and all the other gods who, long ago, went out to seek hikuli. The next morning all wash their faces, heads and hands in water from the hikuli-country, and salute the rising sun with a bowl of burning incense, sprinkling water to the four corners of the world with a flower and praying for life and for luck in hunting deer.35

Meanwhile the patio has been prepared for dancing. Beside the fire are jars of holy water and tesvino, a stuffed fetish-skunk tied to a stick, and a stuffed grey squirrel decorated with dark green beetle wing-covers, small clay birds, feathers and a crucifix."36 The shaman, sitting west of the main fire (behind the usual ceremonial arrows, plumes, tamales, and a pot of hikuli-liquor) sacrifices water to the six regions with a stick; then, with assistants on either side who take turns helping him, the shaman sings the mythological songs, unaccompanied by a drum, and the long dance begins."37 Both sexes take part in the dance, "a quick, jumping walk with frequent jerky turns of the body," in a circle counter-clockwise around the shaman and the fire—though the circle tends to an ellipse as they approach the fetish-animals at the northwest."38

At sunrise of the third and last day comes the corn-roasting ceremony which gives its name to the entire festival, Rarikira (from raki, "toasted corn")."39 The shaman fastens a plume with a ribbon in the hair of the woman who is to do the toasting and gives her a coarse straw whisk to stir the corn on her comal, supported on three stones over the fire. The hikuli-seekers appear with large varicolored ears of corn in their pouches, and after ceremonial circuits they shell it, sacrificing five grains to the fire. The woman then prepares the esquite, and all eat this, together with deer meat and broth, thus ending the festivities.40

The Huichol ritual paraphernalia is heavily symbolized. With his eagle and hawk plumes the singing shaman can see and hear everything anywhere, cure the sick, transform the dead, and even call down the sun; they symbolize the antlers of deer, and deer-antlers in turn symbolize peyote and the "chair" of Grandfather Fire. Peyote itself symbolizes both corn and deer, while the flames of the greatest shaman of all, Grandfather Fire, are his plumes (the brilliantly-colored macao is his particular bird). Deer-antlers, furthermore, for the Huichol symbolize arrows,41 arrows being the symbol par excellence of prayer. Again, arrows symbolize a bird flying with outstretched neck, the feathered portion representing the heart. The peyote plant, finally, is considered the drinking-bowl of the god of fire and wind.42

This intricate symbolic complex (corn = peyote = drinking-bowl of Grandfather Fire = god of wind = whirlwind = deer = deer-tracks = peyote = deer-antlers = shaman's plumes = deer antlers = chair of Grandfather Fire = flames of fire = brilliant bird (macaoj plumes = flying bird = arrow = prayer for rain, corn and deer-hunting, etc.) is deeply rooted in Huichol religion, and each one of the symbolic equations has a ritual reflex."43

TARAHUMARI

Tarahumari peyotism is on the decline in Samachique, Quírara and Guadalupe, though still remaining around Narárachic; in Guadalupe the bakánawa cactus is valued instead. From two or three to a dozen men make the month-long trip to the region around the mouth of the Rio Conchos at any time of the year, though usually not in the rainy season. They first purify themselves with copal incense; on the way anything may be eaten, but in the hikuli country they eat only pifiole, and speech is forbidden. Arrived, they erect a cross near the first plants found, in order to find an abundance of others, and carefully cut off the tops with wooden sticks to leave the roots uninjured. They sing and eat green peyote while gathering it and in the evening they dance the dutubfiri around the cross and a fire. The harvesting lasts several days, some taking turns dancing while the others sleep. Each variety of hikuli is put in a separate bag, for they would fight if mixed."44

The plants are left on a blanket in the mountains near home, and the blood of a slaughtered sheep or goat is sprinkled on them to -feed- them, with a special song. After drying they are placed in covered ollas away from the house. The hikuli-seekers are met on their return with singing, and a fiesta is held with the sacrificial sheep or goat. The dutubilri and the hikuli-dance are then danced all night around a large open-air fire, much green peyote and tesvino being consumed. This ceremony is to "cure" the pilgrims: the shaman's necklace of Coix lachrymajobi seeds is dipped into a bowl of agua-miel, sotoli, or mescal, each one receiving a spoonful, while the shaman sings of hikuli standing on a Job's Tears seed as big as a mountain."45

Tarahumari hikuli-feasts are held at other times also. The women grind the plants with water on a metate into a thickish brown liquid. The dancing-patio is carefully swept with a straw broom and several crosses are planted, and near one of these the peyote is piled with jars of "tea" and tesvino, baskets of unsalted tamales and bowls of meat and "medicine." A large fire is built with logs in an east-west position and hikuli and yumari are danced all night."46

Near the shaman and his assistants who sit west of the fire is a leaf-covered hole into which they carefully spit; the olla-cuspidor of the men to one side and the women to the other is passed around and emptied here also. With a drinking-gourd rim the shaman makes a circle on the ground and in it the right-angled cross of the world-symbol. Then he inverts a gourd over a hikuli placed on the cross, as a resonator for his rasp; hikuli enjoys this music and manifests his strength by the noise produced.47 The shaman's headdress is of bird-plumes, which prevent the wind from entering and causing illness; through them the birds impart to him all their wisdom. The assistants, of both sexes, carry incense bowls of copal, kneeling and crossing themselves at the cross, and then pass out the peyote.48

At times the shaman dances, at times his assistants, and women may dance either separately or simultaneously with the other men participants. The bare-footed men are wrapped to the chin in white blankets; the women wear clean skirts and tunics. The clockwise dancing (with a turn of the body at the shaman's place) consists in a "peculiar quick, jumping march, with short steps, the dancers moving forward one after another, on their toes, and making sharp, jerky movements, without, however, turning around." The men have deer-hoof sonajas, and the rasping and singing are continuous save when the shaman politely excuses himself to the fetish hikuli; others must also ask permission to leave the patio. In the intermittent dancing they beat their mouths with the palm imitating hikuli's talk, or cry "Hikuli vava! (Hikuli over yonder!)" in shrill falsetto.49

At dawn the dancing stops at three raps on the shaman's rasp. All rise and gather at the east cross. Then the shaman, followed by a boy with a gourd of palo hediondo medicine (ohnoa roots steeped in water), "cures" each one with his rasp wetted in the medicine, as they cry, "Thank you!" The shaman makes three long raspings with his stick on the man's head; its dust is so potent in curing that it is carefully gathered from around the resonator and preserved in buckskin bags. A spoonful of other medicines is sometimes swallowed as the shaman blows and makes passes; sometimes tesvino exclusively is used. Blankets are also smoked with copal now. Then, facing the' rising sun, the shaman makes three raspings at arms' length, waving home hikuli who had come from the east early in the morning, riding on green doves, to prevent sorcery in the meeting; now he turns into a ball and returns, accompanied by the owl. Doctoring of the sick as well as "curing" may now occur. Then all wash carefully, and after the shaman sacrifices tortillas and tesvino as they stand in a line facing east, they all participate in a feast.50

COMPARISON OF MEXICAN PEYOTE RITUALS

Huichol peyotism is more intricate and important than Tarahumari, though it is seasonal only and the latter venerated several varieties of cactus. The state of the literature advises caution, but a far better case could be made for the Huichol as a center of diffusion: the neighboring Cora, for example, had a vigorous peyote rite, while the Tubar, who share tesvino and the yohe dance with the Tarahumari and otherwise resemble them culturally, lack it. 51 Beals, however, points out that since the Cora-Huichol do not live within the region of growth of peyote, they must have borrowed it; our sole knowledge of Huichol peyotism is modern, unfortunately, but the Cora rite is known from 1754. On the whole, the gaps in our knowledge are too great to discuss possible centers of diffusion of Mexican peyotism; they may, indeed, lie in the little known area to the northeast.52

A relatively full account of the Tamaulipecan rite is extant :53

One of the Tamaulipecan tribes would usually hold feasts for only those of its own community, or it would invite some of those that were neighbors and friends. They took place generally by night. Devoting two or three previous days to the preparation of a sufficient quantity of peyote, and the gathering of fruits of the season, and in allotting certain fruits of the chase, which, broiled on the hearth that illuminated the feast, were served at a common banquet. The feast always had an object among these peoples. With feasts they celebrated the beginning of summer, which was the season least rigorous for these nude people, or the abundant harvests of corn, or of forest fruits, or their victory in some attack on their enemies. When these feasts were held for one tribe alone they took place commonly in the rancherlas where they lived permanently. But when one who was promoting the feast invited some of his neighbors, then he chose an intermediate point between the two places that they inhabited, and that was picked out generally in the most inaccessible or hidden places in the mountains. As soon as everything was prepared for the banquet and the guests had collected, a great bonfire was lighted. They placed around it the fruits of the hunt prepared before hand. Those that took part in the dance immediately formed a circle around the fire, and to the measured beats of the drum (the drum was made of an aro of wood over which they attached the parchment of a deer or a coyote) which, united with the voices, composed the music. They took part in the dance alternately raising one foot and then the other, or the whole circle started circling around the fire. During the dance dancers and spectators broke out in discordant howls, each one reciting in his own strophes, alluding to the cause that was motivating the feast. Of this versification I have already previously given you an idea: relative to the celebration of some triumph gained in their skirmishes; and in the same way they directed their phrases to the sun, to the moon, and to the clouds, when they were enjoying good weather; to the earth and to the rain when they had an abundance of fruit; and finally to their strength and bravery when they recalled their hunts in the mountains or their wars. The poetic enthusiasm of the guests became more animated with the first fumes of the peyote, which, placed on a counter that was improvised on the trunk of a tree, was served to them by young Indian girls and the old men, and in the same gourds, jars, or rude baked clay vases. This class of feast always used to end with the complete drunkenness of all the guests, who, exhausted moreover by the dance, fell asleep around the almost burnt-out fire. [As previously noted, prophecy was a feature of these rites]. In addition to these feasts that are called mitotes, they also have other games and recreation during the hours of the day, such as ball, fighting, and foot-racing; and these games are often that which gives the motive for their mutual discontent, and sometimes precipitates formal wars among them.

We note in this account the connection of peyote with corn harvests, deer hunting and war; and dancing, racing and a morning ceremony are also mentioned. Regarding the ball-game :54

Among the Acaxee [peyote] was reported to have been placed on one side of a ball ground during a game; its further use here is unknown, but it is likely that it was taken in small doses by the players during the game, as is done in the kicking race of the Tarahumare in modern times.

Chichimecan peyote-eating appears to be connected with war:

Those that eat it or drink it see frightening and laughable visions. This spree lasts two or three days and then stops. It is a common food of the Chichimecas, for it stimulates them and it gives them sufficient spirit to fight and have neither fear, thirst, nor hunger, and they say it guards them from all danger.

The Zacatecan use of peyote seems likewise to pertain to war, since they eat it to learn the outcome of battles. The drugging and ceremonial wounding of the father of a newborn male child, further, is to augur its valor in war. The Caxcane used peyote ceremonially, with associations unknown to us, but the Tlaxcaltecan use points again, though uncertainly, to war. Preuss writes that "the god of the Morning-Star has a close relationship to this cactus, among the Huichol," and the Morning Star has definite war associations.55

Dancing is commonly associated with peyotism in the Mexican area, being recorded for the Comecrudo, Chichimeca, Cora, Huichol, Tamaulipecan, Tarahumari and Lipan."56 Use in ritual racing is known for the Tarahumari, Huichol and Tamaulipecan tribes; and the Acaxee tied strips of deer-hide or -hooves (the word used means either) on the instep as an aid in climbing hills—a custom recalling the carrying of hikuli-deer in racing and the Wichita use of mescal beans. The ritualized journey for peyote is recorded for the Cora, Huichol, Tarahumari, Tepecano and somewhat doubtfully for the Tlaxcaltecan."57

The ceremonial fire has no definitive association with peyotism in Mexico,"58 though it is a prerequisite of the Plains rite even on the hottest summer nights; nor has the copal incense of the Huichol and Tarahumari any relation to the Plains use of sage and cedar."59 The corn shuck cigarette among the Huichol and Tarahumari is, furthermore, in a somewhat different context, though Plains ceremonial cigarettes are certainly Mexico-Southwest in origin." 60 The gourd rattle is Mayo, Tarahumari, Gila River Pima, Walapai, Havasupai, Pueblo, Mescalero, Lipan, Karankawa, Wichita, Seri, Chitimacha, Cherokee, Creek, Koasati and Yuchi (i.e., southern Mexico, the Southwest, peripheral Plains and Southeast) and therefore has no special association with peyote, though again, it may be the origin of the gourd rattle in the central and northern Plains."61 Though the staff is a constant feature in the Plains ceremony, in Mexico 62 this is decidedly not the case. The shaman's rasp among peyote-using tribes is noted only for the Cora, Huichol and Tarahumari—and has a far wider distribution among non-users of peyote, while being absent in the Plains rite."63 The Tamaulipecan aro with drum-head of coyote- or deer-skin is unlike the peyote drum of the north, and further, the use of the drum is untypical in the Mexican rite."64

On the other hand, the use of parched corn is more clearly a part of Mexican peyotism, as is also deer-hunting." 65 "Plant-worship" is most evident perhaps for the Tarahumari, who revere hikuli, bakanawa, mulato, rosapara, sunami, ocoyomi and dekuba; the Tepecano sometimes substitute marihuana or rosa maria (Cannabis sativa) for peyote in their worship, and elsewhere other plants are involved."66 Birds are a recognizable feature in Mexican peyotism: the Huichol macao, humming-bird and swift are noted, and the Tarahumari humming-bird, green dove and owl."67

Bennett and Zingg on the Tarahumari would as well apply to all Mexican peyotism:"68

• . . the use of peyote resembles an elaborate curing ceremony rather than a cult. There is nothing to suggest a society centered around peyote-eating .. The group of peyote-eaters does not involve any exclusiveness, requirements, or ritual pertaining to individuals. The peyote ceremonies are not given for the pleasure of eating the plant, but to cure some disease.

Properly speaking, then, Mexican peyotism is a tribal affair, centering around the shaman, on whose shoulders rests the whole tribal welfare as involved in abundant corn harvests, successful deer-hunting, and success in war (which he may prognosticate)."69 Shamanistic curing is conspicuous in both Huichol and Tarahumari peyotism. Beals,"70 writing of northern Mexico says that

the degree of shamanistic influence apparent at present is greater than at some time in the past. . • Possibly the use of peyote also had some influence in extending and reviving shamanistic concepts. . . . Visionary experiences reach their highest development ordinarily in religions of the shamanistic type.

These remarks go far toward explaining the differential diffusion of peyotism. Peyote never penetrated the Yuman Southwest, perhaps because the dream performed the psychological function of the peyote vision (which, moreover, was not very significant in Mexico). Again, the ritual use of peyote failed to penetrate the Pueblo Southwest or the Aztec, both strongholds of priestly religion; perhaps the stereotyped institutional rituals of these regions stifled such orgiastic individual emotional experiences as peyote is calculated to induce. On the other hand, peyotism entered the shamanistic Southwest (the Mescalero) and one Pueblo, Taos, where the kachina cult was weak, and once it reached the individualistic vision-valuing Plains, it fairly ran riot.

MESCALERO APACHE AND TRANSITIONAL FORMS OF RITUAL

Peyote came to the Mescalero" 71 about 1870, in the same "general movement which resulted in its adoption by a large number of the tribes of the United States."72 Like other Apache ceremonies its origin was attributed to an individual's encounter with a power, but the tribe involved was the Tonkawa, Lipan or "Yaqui." Like the Plains groups, the Mescalero made a trip south to get peyote,"73 which was kept by the shaman for ceremonial use only, lest private individual users who did not "know" and have the right to use the power go mad. The primary purpose of meetings was for doctoring,74 though "occasionally a peyote meeting was called for some other purpose—for peyote, like other sources of supernatural power, was believed to be efficacious for locating the enemy, finding lost objects, foretelling the results of a venture, etc."

The news that a peyote shaman is conducting a meeting for a sick person spreads rapidly, and all who are to attend bathe at noon of the appointed day.75 At nightfall they enter the tipi, where the peyote chief is sitting west of the fire facing the door, with a gourd rattle in one hand and an incised wooden staff in the other."76 The staff is his protection against witchcraft, and he "sings to it"; he exchanges the gourd for the drum of his assistant, but retains the staff in his left hand. In front of him on an eagle feather or piece of buckskin lies the large talismanic "chief peyote" or "Old Man Peyote."77

He is assisted by a door-keeper and a fire-tender, who builds a crescent mound of earth around the fire-pit with the horns east, and keeps the fire going all night."78 Once having entered, one is not supposed to leave the tipi until morning save briefly, taking one of the eagle feathers lying on either side of the door, and replacing it as soon as possible. The peyote,"79 in a sack or on a woven tray, is first eaten by the peyote chief, who then ad, ministers their first buttons to novices, using two eagle-tail feathers as a spoon, with three ritual feints, after which these "fly" into their mouths. Then after smoking"80 the peyote is passed around by the assistants as the leader prays. Beginning at the southeast the drum is passed clockwise as each person sings four songs, his own ceremonial songs or songs received in visions, while the leader or his assistants shakes the rattle. The leader sings most of the songs.

There was a mild bias against women"81 among the Mescalero; they received medicine power, but could not become a peyote chief, because the responsibilities of the office were too great—for a leader must prevent anything happening between even the greatest of rival shamans in meetings." In this he was aided by the chief peyote which "he frequently consulted. . . to ascertain whether anything were amiss; any evil thoughts or efforts at witchcraft were said to 'show' on this 'chief peyote'." A favorite device of witches to weaken the leader was to make his assistants vomit the peyote.

Peyotism was readily accepted by the Mescalero, in whose older culture were patterns of receiving supernatural power from animals, etc. Indeed, Opler calls the Mescalero

a tribe of shamans, active or potentially active [and peyote became another among many sources of power for them]. It will be readily grasped, however, that since peyote leadership and the conduct of peyote rites were open to any one who claimed a supernatural experience with the plant, since, in other words, an individualistic, shamanistic premise underlay the utilization of peyote for religious purposes, centralized leadership and definite organization could not be achieved. The Mescalero use of peyote never developed into a cult or society with a regular membership and place of meeting, with officers and principals selected or agreeable to the entire body of devotees . . . [even with the] emphasis on curative rites. . . .

This, in Mexico, made the rite tend to be tribal in character, the shaman quasi-priest. Mescalero peyotism, therefore, is truly transitional between the Mexican all-inclusive rite of tribal cure and the individualistic Plains societal ceremony; no equilibrium was permanently reached between the two, and Opler adduces abundant evidence of the rival nature of peyotism among competing shamans.83 The concept was that everyone was to get in rapport with his power(s) via peyote, with the peyote shaman, however, remaining the figurehead leader—a multiple "working together" of powers, peyote being the power par excellence that worked with other powers. The Mescalero, then, attempted to force the physiologically somewhat refractory individual peyote experience into the shamanistic mold. The leader remained the arbiter and mediator, and held special symbols of authority, the staff and the rattle, to compensate for his real loss of status as cynosure, when participants in the curing rite were enlarged beyond the patient and his relatives.

Notable is the lack of Christian elements in Mescalero peyotism, in contrast with some Plains groups; indeed, "far from becoming a weakened and Christianized version of native beliefs, the Mescalero Apache acceptance of peyote resulted instead in an intensification of the aboriginal religious values at many points."" On the other hand, when we recalled the history of their relations with Whites and such psychologically similar cults as the Ghost Dance of the Plateau, Great Basin and Plains, it is somewhat surprising that a warlike and predatory group like the Mescalero did not associate peyote and anti-White feeling. Opler has recorded a Tonkawa peyote ceremony with clear anti-White features; but the Mescalero had an aboriginal ceremony before peyote whose function was the consternation and defeat of enemies, and this, directed toward the whites, usurped the function of ritual opposition through peyote.85

KIOWA, COMANCHE TYPE RITE

Aside from the John Wilson, John Rave, and Church of the First-born variants, the basic Plains ceremony is remarkably homogeneous in various tribes. Since the Kiowa and the Comanche, historically considered, were the center of this diffusion86" in the interests of economy we choose their ceremony to detail as the "Plains type-rite." In the following account care is taken that every statement be specifically true of the Kiowa and at the same time representative of the Plains; minor Comanche differences are shown in footnotes.

Living beyond the habitat of peyote, all Plains tribes have to make pilgrimages for it or buy it. The journey is not ritualized, but there is a modest ceremony at the site: on finding the first plant, a Kiowa pilgrim sits west of it, rolls a cornshuck cigarette and prays, "I have found you, now open up, show me where the rest of you are;87 I want to use you to pray for the health of my people." He sings and eats green plants while harvesting them; only the tops are taken, that the root may regenerate buds, a fine large one being saved as a "father peyote" for meetings later."88

Many groups, like the Kiowa, "vow" meetings as in the Sun Dance. They may be held in gratitude for recovery from illness, on a child's first four birthdays, for doctoring the sick, to pray for the successful delivery of a child, or for the health of the participants in general. Present too is the possibility of instruction and power through a peyote vision; in the Plains this is the primary motive, with doctoring second. In the last twenty years "holiday meetings" have been introduced."89

In preparation, the Kiowa commonly take a sweatbath."90 In the old days buckskin dress was prescribed, but nowadays a "blanket" or folded sheet for men and a shawl for women satisfies this requirement; buckskin moccasins are more comfortable than stiff-soled shoes during a night spent sitting cross-legged. Older men still paint for meetings; one leader for example had a yellow hair-part with a short red forehead line perpendicular to this, vertical red lines in front of the ears, and yellow around the eyes.91

The sponsor selects his leader (nOtki) or himself acts as one; a leader usually has his own drummer (o'n'asodeki) and fireman (n'in'uki), and some a "cedar man" also. The sponsor's womenfolk erect the tipi, prepare and bring the food and water the next morning. The floor is carefully cleaned and plumes of sagebrush are spread around the inside of the tipi, as in a sweat-lodge, for a seat. The sponsor stands the cost of the meeting (from twenty-five to fifty dollars), or others may help in paying; he also supplies the peyote or pays the leader for it, but communicants often bring their own buttons also.

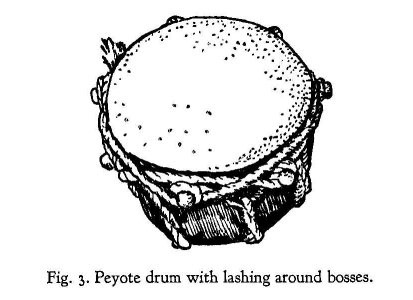

The leader supplies the paraphernalia: the staff (no'q a, "brace-to hold-stick") of bois d'arc, the gourd rattle, eagle wing-bone whistle, cedar incense, altar cloth, drum, and perhaps his personal "feathers" for doctoring. The drum (ncafnco or sc'oXkcaucoasnco) is a No. 6 cast-iron three-legged trade-kettle with the bail-ears filed off. The buckskin head is well soaked and tied over the kettle, a third- or half-filled with water into which ten or a dozen live coals (and sometimes herb-perfumes) have been dropped; the Kiowa say the drum represents thunder, the water in it rain, and the coals lightning. Seven marbles are put under the buckskin around the outside kettle rim to serve as bosses for the thong wound once-anda-half times round them; the same thong is passed through each loop and laced criss-cross seven times under the kettle, unknotted, to tighten the head and form on the bottom the seven-pointed "Morning Star." The single drumstick (scAkatcon) is straight, carved, beaded, and embellished with a buckskin tassel or fringe on the handle end. The gourd-handle is also beaded and fringed, and tufted with red horse-hair (nuXks'ggYä) at the top end passing through the gourd, the neck of which is plugged with half a spool; the gourd itself may be covered with texts or symbolical drawings.92 Participants are free after midnight to use the cult drumstick and gourd or their individual ones as they choose. Formerly "only the leader brought in the medicine fan with him, but now many young men bring them in who have no special business to."93 These have a beaded and fringed cylindrical handle, with feathers loosely supported in individual buckskin sockets sewed around the shafts; often they are notched, tipped with horse-hair, or down feathers are added at the base—as individual "visions" dictate. The leader also supplies the fetish "father peyote," but no Bible is used in the Kiowa or usual Plains ceremony.93 Formerly only old men and warriors attended meetings, but now women and girls over thirteen come in, when not menstruating, though they may not sing the songs or use the paraphernalia.94

The tipi is entered any time after nightfall, with a preliminary clockwise circuit outside as in the sweatbath (all circuits inside must be clockwise also). Sometimes several line up behind the leader, who prays briefly: "I am going into my place of worship. Be with us tonight." Entrance however is often informal and made one by one, before the leader comes in with his rattle and staff in one hand, and his paraphernalia-satche 95 in the other; he sits west of the fire, which has been started by the fireman, north of the door, who comes in first of all. His drummer is south of him, to his right, his cedar-man (if there is one) north and left. Others enter and informally take places, but after he is seated they kneel on the right knee at the door for a moment, looking to him for permission to enter and be assigned a place; the sponsor meanwhile may call out, "Come in! So-and-so," to these, informally welcoming them. A tipi some twenty-five feet in diameter seats thirty people comfortably. In summer the sides are raised to allow a breeze to blow through.

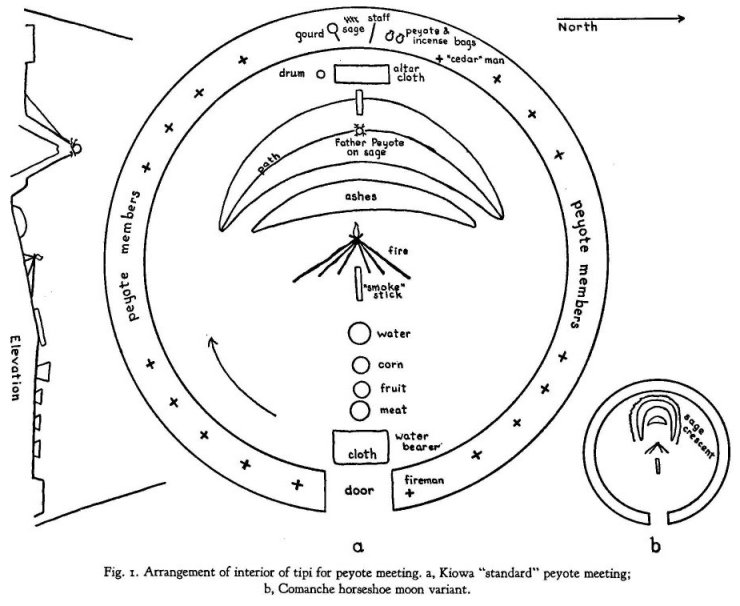

At the west center, horns to the east, is the crescent altar 96 (piktbw) with a groove or "path" (G'comhon.) along it from horn to horn, interrupted by a flat space in the center where the "father peyote" is later to rest on sprigs of sage. The "path" symbolizes man's path from birth (southern tip) to the crest of maturity and knowledge (at the place of the peyote) and thence downward again to the ground through old age to death (northern tip). The crescent, carefully shaped beforehand by the fireman out of clayey earth, also represents the mountain range of the origin story where sgriqyi or "Peyote Woman" first discovered the plant. East of it in a shelving depression is a fire, constantly mended by the "fire-chief" during the night to keep it in a worm-fence arrangement, the closest approximation to the ritual crescent-shape possible with straight sticks The accumulating ashes are shaped with great care into another crescent between fire and altar. A "smokestick"97 is kept smoldering in an east-west position close to the fire to light all cigarettes.

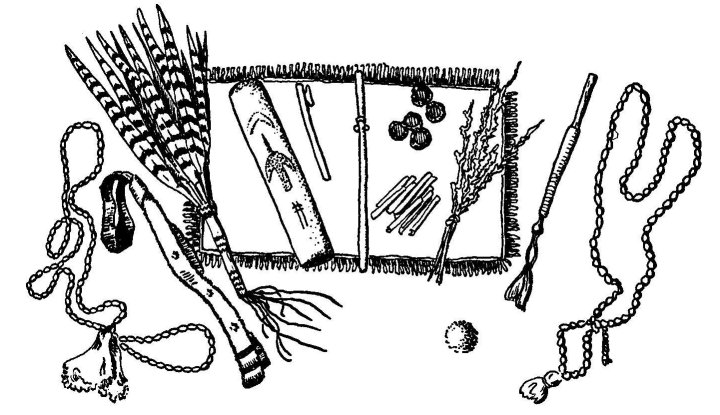

Fig. a. Peyote paraphernalia. Left to right, Mescal bean necklace; "peyote" necktie from a strip of trade, blanket with selvage stripes, and beadwork representing peyote buttons; beaded and fringed pheasant feather fan; black velvet, gold,fringed altar cloth; smokestick carved with water bird, etc., eagle bone whistle; drumstick; peyote buttons; corn husk cigarette "papers"; bundle of sage plumes; pile of powdered cedar incense; a beaded, fringed, and carved drumstick; mescal bean necklace.

All seated, the leader places the father peyote on the sage sprigs, orienting it by the thorn or mark made when he cut it."98 After this the ceremony is considered begun, all informal talking and joking ceases, and others entering are late-comers. Everyone begins to stare at the fetish peyote and the flickering fire." Then the leader leans his eagle-humerus whistle against the west outside of the moon, mouth end up, takes out his cedar incense bag, gourd, tobacco, etc., and arranges them conveniently near him.

The first ceremony is smoking or praying together. The leader makes himself a cigarette of Bull Durham with corn husk "papers" dried and cut to shape, and passes the makings clockwise to the rest, including women.'" His own made, the fireman presents the smoke-stick to the leader (who may first offer it courteously to his drummer) and this too is passed to the left. While all smoke, the leader prays: "beha'be sti'Doki (smoke, peyote power). Be with us when we pray tonight. Tell your father to look at us and listen to our prayers." He holds his cigarette mouth end toward the peyote and motions upward that it may smoke as he prays:

We are just beginning our prayer meeting. We want you to be with us tonight and help us. We want no one to be sick at this meeting from eating peyote. I will pause again at midmight to pray to you. I will pause again in the morning to pray to you. [Then he prays for the person who is sick or whose birthday the meeting celebrates or for relatives and participants.] If there are any rules connected with you, peyote, that we don't know of, forgive us if we should break them, as we are ignorant.

All pray silently to o6mooki, "earth-creator" or "earth-lord," and older men may add their prayers aloud after the leader. Then, following the leader, all snuff their cigarettes in the ground and place them on the west curve of the altar, outside, or at either horn; the fireman may gather those of women, old people or visitors.

The incense-blessing ceremony immediately follows. The leader (or his "cedar-man") sprinkles some dried and rubbed cedar on the fire; then he makes four clockwise motions of the peyote bag toward the fire, takes out four buttons and passes the bag. Kneeling on both knees, he reaches down beneath the hides or blankets of the seat, and bruises a tuft of sage between his palms, and smelling it with deep inhalations, rubs his hands over and down his head, breast, shoulders and arms, with outward downward movements, ending with the thighs. Though the peyote may not yet have reached them, the others follow suit, reaching out their palms to absorb the blessing of the incense and rubbing themselves.

This done, all eat"' their peyote, to the accompaniment of much spitting out of the woolly center of the buttons; hereafter during the night in the intermissions of singing, anyone can call for the peyote bag (the incense burning may or may not be repeated). Then more cedar is sprinkled on the fire and the leader makes four motions with the staff in his left hand and the rattle in his right toward the rising incense smoke.' °2 The drummer motions similarly with the drumstick, pulling smoke from the fire to the drum. The leader takes a bunch of sagebrush from between the tipi-cover and pole behind him (previously prepared by the fireman), holds it with his staff and the singing begins."3 The drummer shifts his left thumb over the drumhead or sloshes the water inside on it or blows on it to get the proper tension and tone, then the leader holds his staff and sage at arm's length between himself and the fire and rattles for the Hayainayo or Opening Song.'" The leader exchanges his staff and rattle for the drum the latter always passing under the staff,"5 and the drummer sings four songs of his own choosing. The paraphernalia, staff preceding drum, are then passed to the left; each man sings to the drumming of the man on his right, and then himself drums for the man on his left."' This singing, rattling, and drumming forms the bulk of the ceremony during the night. At intervals older men pray aloud, with affecting sincerity, often with tears running down their cheeks, their voices choked with emotion, and their bodies swaying with earnestness as they gesture and stretch out their arms to invoke the aid of Peyote. The tone is of a poor and pitiful person humbly asking the aid and pity of a great power, and absolutely no shame whatever is felt by anyone when a grown man breaks down into loud sobbing during his prayer.'"

About midnight the leader announces that he is going to put incense on the fire after the next four songs, and when he does, everyone blesses himself in the smoke. The announcement gives the fireman time to mend the fire and build up the ash moon'" and sweep the cigarette butts into the fire. If the paraphernalia are north of the door they are passed backwards to the leader drum first, if at the south (i.e. past the door) clockwise and staff first as usual. Smoking stops, and the leader, to the drumming of his assistant, sings the Midnight Song."9 When the first of the four is finished, the fireman (sometimes given a feather for this errand by the leader) leaves, gets a bucket of water, returns, sets it in front of the fire and unfolds a blanket on which he sits in line with it facing west. The leader, finishing the second song, blows four increasingly loud blasts on the eagle wing-bone whistle (to imitate the water bird) then replaces it by the peyote and sings the last two songs. While his assistant holds the staff and gourd, he spreads an altar cloth just west of the fetish, and places on this the staff, gourd, sage and his fan, together with the "feathers" of communicants passed to him for this purpose; the drum is to the south of this, the drumstick, etc., on the cloth.

After cedar-incensing, the fireman makes a smoke, puffs four times and prays, thanking those responsible for the honor of being chosen fire-chief, and praying for the leader and his family, the sick and the absent. Next the leader prays, then the drummer, using the same cigarette, and to complete the figure of a cross, the man to the north or "cedar-man" prays. When the butt is placed by the altar, the fireman makes a circuit of the altar and passes the bucket to the man south of the door. Quiet conversation is permitted in the somewhat informal drinking period."° When the fireman has drunk, the leader passes back the fans and the paraphernalia to where the singing had been interrupted, and leaves the tipi. He goes about thirty feet east of the tipi, whistles four times and prays, repeating this at the south, west and north." When four songs are completed, he returns, blessing himself in the incense smoke which the drummer throws on the fire."2 Now is the preferred time to leave the tipi and stretch cramped legs. Singing continues as before until dawn.

As the first grey light appears, the leader tells the fireman to waken or notify the woman who is to bring the water (she has no special seat, if she has attended the meeting). The fireman always brings the midnight water, a woman that at dawn."' The leader whistles four times, even in the middle of a song, when the fireman tells him she has arrived outside. When the singer finishes his four songs, the leader calls for the paraphernalia and sings the four Morning Songs; after the first of these the woman enters, arranges a blanket and sits as did the fireman. Finishing the three remaining songs, the leader calls for feathers and spreads them with the paraphernalia on the altar cloth, as at midnight. A smoke is made for the woman, who thereupon prays, after which the leader and his assistants smoke it. Doctoring114 is best done at this time; the leader may do this, or he may ask an older man to fan the patient with consecrated feathers from the altar cloth.

Then the fireman spills a little water before the fire, the woman drinks, and the bucket moves clockwise as before from south of the door. The woman makes a circuit of the altar, picks up her blanket and takes the bucket out. The feathers are passed out again, and the paraphernalia returned to the place of the next singers in the circle (because of such ritual interruptions, praying, passing of peyote, etc., a complete round of the drum requires two or three hours).

While waiting for the ritual breakfast, the meeting is again somewhat informal. Several women may leave to help the water-woman prepare the food, and younger men may go outside for a stroll and a secular smoke. Old men often lecture younger members on behavior at this time, "preaching" directly to a relative, and more indirectly to others.115 When he has finished another old man may exhort: "You must do as that old man has said. He's had experience. What he's telling you is good." At this time too visitors are given opportunity to express gratitude for the hospitality of their host, who in turn thanks them for coming.

When the food arrives outside, the fireman notifies the leader, who calls for the paraphernalia and sings four songs, the last of which is the Quitting Song. The food meanwhile is passed in and placed in line with the father-peyote and fire, west-to-east thus: water, parched corn in syrup, fruit and meat."6 No one sits east of it as in the water ceremonies. The four songs completed, the leader tells the drummer to unlace the drum, and all the paraphernalia are passed around (between the food and the fire at the east) for everyone to handle,"7 as an older woman ("because food is their life-work") or a Ten-Medicine keeper, who typically functions at such Kiowa group-prayers, asks a blessing. The leader then removes the father peyote from the altar, and when he puts it in his satchel with the rest of the paraphernalia the meeting is ended.

Complete social informality now reigns as the food is passed to the man south of the door and thence clockwise. Much joking"8 goes on during this meal, which has none of the seriousness of the Christian partaking of the Host. When the fireman has finished eating, at the leader's instruction, he leads the line out of the tipi."9 The tipi may be taken down immediately, or moved bodily a little, but the older men drift back into its shade and lie around talking and exchanging peyote experiences."° As meetings are ordinarily held on Saturday nights, Sunday forenoon is free for such visiting, talking and dozing under arbors. Nearly everyone stays for a secular dinner at noon, and they take home what they cannot eat; sometimes other guests come who have not attended the meeting.

COMPARISON OP MEXICAN, TRANSITIONAL, AND PLAINS PEYOTISM

Having now characterized the Huichol-Tarahumari type-rite for Mexico, the LipanMescalero for the transitional nomad Southwest, and the Kiowa-Comanche as the historical prototype for the Plains, we may attempt a comparison and contrasting of them.

In Mexico as a whole "curing" is perhaps the most salient characteristic, while both curing and doctoring are conspicuous in Mescalero. In the Plains, while doctoring is an important feature it is by no means indispensable.'" Peyotism in Mexico, therefore, has a tribal character, while in Mescalero the ceremony is a forum for rival shamans—a trait not altogether absent in early Plains rites—and in the Plains peyotism has a societal nature. These facts have an important bearing on the cultural manifestations of the physiological action of peyote. In Mexico visions are turned to the uses of prophecy ;122 in Mescalero they enable a shaman to detect rival witchcraft; while in the Plains, visions are a source of individual power. These categories should not be made too rigid, however, for clairvoy • ance, if not prophecy, as well as witchcraft anxiety are known for early Plains peyotism, and on the other hand, peyote medicine-power is a source of Mescalero shamanistic rivalry. Yet as indications of relative emphasis these statements might be allowed to stand.

The Mexican symbolisms point to an association with hunting, agriculture and gathering activities, and the typical anxiety expressed in the religion is the desire for rain. In Mescalero, peyote is the focal point for the warfare of antagonistic powers, and expresses the mutal suspicion of formerly small local groups; the intense and ever-present anxiety is the fear of aggression and reprisal by witchcraft. In the early Plains peyote ceremonies, associations with warfare were prominent (influenced no doubt by a forerunner of peyotism there, the mescal bean ceremonialism), though in later times this element had become so nearly absent that Mooney could point quite properly to the "international" character of the cult in his time.123

Areal contrasts in minor points are no less striking. Dancing was conspicuous in Mexico, less important transitionally, and on the whole lacking in the Plains Painting of a symbolic nature was ritually significant in Mexico; in the Plains individual styles were dictated by peyote visions. Peyotism in Mexico is a seasonal matter, but in the Plains the rite occurs the year around (in the south the trip for peyote may have been associated more with the ritual salt pilgrimage, in the north with the ritualized war journeys; parallels are also suggested in the Maricopa ritualized mountain-sheep hunting and Navaho deer hunting).

In Mexico peyote wag a tribal affair and women participated on equal terms with the men in dancing, etc. In Mescalero, women were excluded from meetings, as in the Plains also originally. The rite was held principally outdoors in Mexico, and in a tipi transitionally and in the Plains—a patio arrangement in Mexico, and an altar centering around the "moon" in the Plains. Ritual racing and ball games.'" are part of Mexican peyotism, but not elsewhere. Smoking is inconspicuous in Mexico, but in the Plains it has been important enough to involve church schisms.'25 Huichol peyote had no drum, though elsewhere in Mexico a wooden drum was used, while in the Plains the water-drum (intrusive from the Southwest) is universal. The rasp is Mexican, but the Plains rite has the gourd rattle and eagle wing-bone whistle in addition to the drum. The "staff" is a special problem in the Plains.

The Huichol and Tarahumari have a squirrel fetish in addition to the fetish plant; the Plains have only the latter. Ceremonial drunkenness with tesvino, etc., is an integral part of Mexican "curing"; in the Plains peyote and alcohol are so far mutually exclusive that the familiar propaganda calls the first a specific against the second. The alleged aphrodisiac virtue of peyote is a Mexican belief; but curiously enough in Mexico, where many "peyotes" were said by natives to be aphrodisiac, Lumholtz pronounced Lophophora wil/iamsii definitely anaphrodisiac; while in the Plains, where the natives most strenuously deny this virtue for peyote, enemies of the cult most consistently claim that it produces aphrodisiac orgies.'"

In Mexico the shaman alone sings, though his assistants may "spell" him; in the Plains all male participants drum and rattle. In Mescalero, though the drum circles the tipi, the staff and gourd remain with the leader. Finally, Mexican and Mescalero peyotism are almost wholly free of Christian elements; so too were the early Plains rites diffusing from the Kiowa-Comanche, though in the John Wilson rite, the Oto Church of the First-born (and its successor, the Native American Church) and the Winnebago Rave-Hensley variant, Christian symbolism and interpretations are frequent.

Common elements are numerous: the ceremonial trip for peyote (more elaborate in Mexico, to be sure), the meeting held at night, the fetish peyote, the use of feathers and the abundance of symbolisms connected with birds, the ritual circuit, ceremonial fire and incensing, water ceremonies, the "Peyote Woman," morning "baptism" or "curing" rites, "talking" peyote, abstinence from salt, ritual breakfast, singing, tobacco ceremonials, public confession of sins, Morning Star symbolisms, and (for nothern Mexico) the crescent moon"' altar. The fear of being blinded by the peyote-fuzz is Mescalero, Lipan and Plains, and the water-drum is shared by both non-peyote Southwestern groups and those of the Plains who have the peyote rite. The use of parched corn in sugar water, boneless, sweetened meat and fruit for the "peyote breakfast- may be regarded as universal for peyotism, wherever found.

1 Rouhier (Monographie, 91, n. i) argues immense antiquity for peyotism, circa 300 years B.C., among the Chichimeca on quasi-historical grounds. Our knowledge of peyote from Spanish documents goes back to the sixteenth century in Mexico. A manuscript in the Library of Congress reports the trial of a Taos Indian, February 3-8, 1719, for having "taken peyote and disturbed the town" (cf. Twitchell, Spanish Archives, a: 188). See Bandelier, Manuscript; Mooney, Tarumari-Guayachic.

2 Adapted from Lewin, Phantastica, 96, and Nicolas de León in Brinton, Nagualism, 6.

3 Hernandez, De Historia Plantarum, 3: 70.

4 Arlegui, Crkica, 154-55 in Urbina, El Peyote y el Ololiuhqui, 26.

5 Prieto, Historia y Estadistica, 123-24, in Mooney, Peyote Notebook.

6 Alarcón, Tratado de los supersticiones, 195.

7 Lindquist, The Red Man, 70-71, is in error in stating that the Zurii use peyote for religious purposes; moreover the document of 1720 cited refers to Taos, not Zurii. Mr. An-che Li assures me that the Zurii lack peyote even today. Lindquist has evidently confused peyote with datura; see for example Safford, Narcotic Plants, 405, 406. Still other plants, e.g., datura, cohoba snuff, coca, yahé, aya-huasca, etc., were used in Middle America as prophetic aids; see for example Safford, op. cit., 393; Gayton, Narcotic Plant Datura.

8 Bennett and Zingg (The Tarahumara, 135) write that "in a culture where animals are thought to talk and cattle are supposed to warn their masters of impending drought or plague, it is not surprising that plants also are imbued with personality and harmful or helpful attributes. The small ball of cacti is especially revered by the Tarahumara." Some Mammillaria spp. have a striking resemblance to a head of hair; one figured in Higgins with flowing white "hair" is called "Old Man Cactus"; again, natives have an intense fear of even touching these plants—an attitude recalling the Pima belief that even one drop of Apache blood falling on a person would make him ill (Hrdli&a, Physiological and Medical Observations, 243). In this connection it is interesting to note that Spier has collected evidence bearing on the magical use of enemies' scalps. The magical malevolence of the enemy or his scalp is cited (Warfare) for the Maricopa, Yuman and Piman groups, Navaho, Jicarilla, and Pueblo. The Yumans and Pimans required stringent purification from contact with the enemy or his scalp; the Pimans, again, along with the Navaho and Pueblos turned this power to account in curing and rain-bringing. Spier states that for the Pima-Papago the scalp is turned into an ally against the enemy, and made a specific prophylactic against such enemy-engendered dangers as paralysis, swooning at the sight of blood or a violent death; the Maricopa, indeed, convert a scalp into one of themselves, much as a captive is ceremonially converted and purified. Further still, according to Spier, the Maricopa and Yumans received prophetic foreknowledge of the enemy from these scalps, which therefore they carried with them to war. Still more strikingly, scalps are thought to laugh and cry and babble incessantly, much as the noisily talkative peyote plant is supposed to do.

9 Lumholtz, Tarahumari Dances, 452; also Unknown Mexico, 1:372-74.

10 Spier (Warfare) writes that "Clairvoyance on the part of the shaman who accompanied a war party is noted for Maricopa, Yuma, Pima, and Papago [as well as] in the Plains and Plateau." Zutii war chiefs, he adds, sought sound-omens on the eve of setting out on the warpath. In this last connection the detailed similarities in attitude and conduct of war-expeditions, peyote-pilgrimages, and salt-gathering expeditions in Mexico and the Southwest should not be overlooked. (The Huichol shooting of the peyote plant, however, is a hunting rather than a war symbolism, that of hunting the hikuli-deer of the peyote origin legend.) Information on the Comanche horse-raid is from E. A. Hoebel; unfortunately the Government took most of these peyote-given horses back again.

In the 1850's the only Kiowa who ate peyote was Big Horse. When he wished to know the whereabouts of an absent war party he would take a drum and a rattle into a tipi, saying "rägllnbonta" (I am going to look for medicine), eating peyote and afterward telling what he had seen; sometimes he made the sound of an eagle, the bird that flies high above the earth and sees afar.

C. W., president of the Kickapoo Native American Church, often has prophetic peyote visions; Kishkaton says they are of "Judgment Day" when the "new world" will come, and makes them a proselytizing argument for peyote. The debt to earlier Kickapoo prophets is obvious. A specific Caddo prophecy among the visions collected would have prevented a serious industrial accident if it had been properly interpreted.

11 In the Plains the "father peyote" is often carried as a fetish. Kroeber (Arapaho, 406) cites a typical case: "The pouches used to contain the peyote plant have room for only one of the disks, which is usually carried more or less as a personal amulet, in addition to being the center of worship during ceremonies. A circular area of beadwork covering the front of the pouch itself, is said to represent the appearance of a peyote-plant while being worshipped. In the center a cross of red beads represents the morning star. Around the edge of this circular beadwork are eight small triangular figures, which denote the vomitings deposited by the ring of worshippers around the inside of the tent in the course of the night. The yellow fringe around the pouch represents the sun's rays."

War Eagle, Delaware (Speck, Delaware Peyote Symbolism) told of a man gassed in the World War whom peyote cured after his case had been pronounced hopeless. Quanah Parker, the famous Comanche chief, used to carry a peyote on his chest as protection in battle. A Ponca story tells of J. W. and his wife returning home as a cyclone was coming up; when they finally arrived the house was destroyed, but in an undisturbed drawer they found four articles still intact: a "peyote chief," a bag of peyotes, a Bible, and a peyote drum-stick.

12 Sahagan, Historia general, 3: 41; Histoire générale, 737. Lumholtz (Unknown Mexico, 2: 354) adds marihuana to the list of plants which protect against witchcraft injury: the doctor comes on a Tuesday, Thursday or Friday, reverses the ill person's sandals, shirt and drawers, recites the credo backwards to summon the owl, and burns a heap of marihuana and old rags in the house. Many persons also carry marihuana in their girdles as a protection against sorcery. The Cocopa and Yuma uses of an unidentified plant (awimimedje) to offset fatigue and give luck suggests peyote (Gifford, Cocopa, 268).

13 De la Serna, in Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 39o; Arlegui in Urbina, El Peyote y el Ololiuhqui, 26; Arias, in Urbina, loc. cit.

14 See the modern Tepecano votive bowl altar used with peyote or marihuana (Lumholtz, Unknown

Mexico, 2: 124-25)•

15 Lumholtz, op. cit., I: 284-85. The Wichita use the "mescal bean" in racing, and the Kiowa as a prophylactic against stepping on menstrual blood. Peyote is associated with racing in Mexico by the Huichol, Tamaulipecans, and Tarahumari (Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 2:49-50; Prieto, Historia y Estadistica, 123-24; Lumholtz, op. cit., : 372; Bennett and Zingg, Tarahumara, x36-37, 295, 338).

16 A Wichita leader envisioned a flag three months before being drafted into the army; the fetish-peyote he carried over-seas miraculously escaped confiscation during an inspection and disinfection of clothing, and because of it he was only slightly wounded in battle. One meeting I attended was in performance of a vow if the Bonus legislation then pending would pass. This same leader prophetically dreamt of how peyote would protect him on a pilgrimage to Mexico and aid him through the customs with a supply of plants, and all happened as predicted.

The Tarahumari dare not touch the deküba (datura) plant lest they go crazy or die; this presents a problem since the plants are common in their winter caves. The peyote shaman, however, armed with the more powerful plant uproots the datura with impunity. Peyote is the only cure for the otherwise fatal disease which comes from touching deküba (Bennett and Zingg, op. cit., 138, 294).

17 Hoebel, Comanche Field Notes; Voegelin, Shawnee Field Notes. The Iowa Red Bean medicine bundle was used for war, horse stealing, hunting and horse racing (Skinner, Ethnology of the loway Indians, 245-47, Societies of the Iowa, 718-19). A similar mescal war bundle and cult was present among the neighboring and related Oto. The Red Medicine bundles of the Pawnee contained mescal beans likewise; indeed the Pawnee are thought to be the origin of the Iowa bundle and associated war-dance. The Pawnee "kill" the beans by breaking and stirring them in a large kettle, drinking the concoction toward morning until they vomit, to "clean out" the body. There is an unmistakable similarity to the "black drink" ritual vomiting here (see Appendix 4).

18 Mulato, sunami, and rosapara cacti, however, protect against Apache machinations; Mooney (TarumariGuayachic) cites a Chalája arroyo near Conaguchi (from chärä or chälä, "squirrel," the epithet of witches) where witches were formerly burned; cf. the use of the squirrel-fetish in the Tarahumari peyote ritual. In Tamaulipas intertribal peace was so precarious that peyote mitotes were commonly held in remote and inaccessible intermediate mountain regions; the recital of war deeds was sometimes part of the rite (Prieto, in Mooney, TarumariGuayachic). De la Serna (in Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 3 io) describes the use of teomanacatl in witching. For Tarahumari witching with hikuli see Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 1:314, 323-24, 371-72.

19 A favorite diversion of witches to weaken the leader was to make his assistants vomit (Opler, The Influence of Aboriginal Pattern). My Kiowa companion vomited in a Ponca meeting, the first he had ever attended in that tribe. He attributed it to their unfriendly feeling and felt considerably relieved when we visited next morning a meeting held by old friends among the Oto; but he himself had once witched a Comanche in a meeting (Autobiography of a Kiowa Indian). Tonkawa data is from Opler, Autobiography of a Chiricahua Apache. The exploits of the Kiowa witch Tonakat have already been mentioned. The Comanche "used it in the old times, but not rightly; the medicine men used it for sorcery, so people got scared and stopped using it" (Hoebel, Comanche Field Notes). Among the Cheyenne, Flacco and Cloud Chief strongly opposed the introduction of peyote; the former said "it was used to witch people and make them crazy." The Northern Cheyenne (Hoebel, Field Notes) and Lipan (Opler, The Use of Peyote) and Winnebago -fear states" may have a physiological basis.

Mrs. Voegelin (Shawnee Field Notes) quotes an informant: "Wilson showed them how to swallow mescal beads . . . N. S. didn't go; she was afraid of them. The Delaware had it too; she never wanted to go look. John Wilson also taught them how to shoot a person with red beads two inches long; the person would fall down, hard; then John Wilson doctored on them with medicine. [Several Shawnee] crept up in the grass when the Quapaws were holding a Ghost Dance once, at night. S's wife got shot. . . . Finally some one spoke to John Wilson, "You men, you abuse the women." An old Peoria woman who went all the time, and swallowed those red beads—she was kind of crazy—told Wilson that. The agent finally stopped it . . . When they were shot, John Wilson used peyote to bring them back."

20 Alegre, Historia de la Comparda, 2: 2'9-20; Prieto, Historia y Estadistica, 131. It is not proven that peyote applied externally has an anaesthetic or anodyne action (the Zacatecan use in the child-birth ceremony is internal); but natives recognize the ability of peyote to induce a stuporous state. The Aztec (Gerste, Notes sur le medicine, p) used peyote to stupify sacrificial victims. But peyote does not cause sleepiness, and the following Maratine Indian battle song (in Prieto, op. cit., 219-2o; Mooney, Peyote Notebook) should perhaps be translated "become stuporous:" "The women and ourselves shouting with pleasure, Shall drink peyote and shall fall asleep." For Opata data see Ensayo, in Mooney, Tarumari-Guayachic; for Lipan see Opler, The Use of Peyote.

21 Parsons, Taos Pueblo, 59; Flores, in Urbina, El Peyote y el Oloiiuhqui, 26; Rouhier (Monographic, 9ó) adds the Caxcane use "for swellings and spasms"; Hernandez, De Historia Plantarum, 3: 70; Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 295; Bennett and Zingg, The Tarahumara, 294; Hrdli6ka, Physiological and Medical Observations, In, 242, 244, 250, 251; Lumholtz, The Huichol, 9; Unknown Mexico, 2: 141-42.

22 Would pupil-dilation from peyote cause temporary "cures" satisfying the uncritical?

23 Radin, Crashing Thunder, 183, 19ó; Mooney, The Mescal Plant, 9. Lumholtz (Unknown Mexico, 2: 157) himself confidently prescribed peyote for a scorpion-sting.

24 Beals, Comparative Ethnology, i3i (Acaxee); Rouhier, Monographie, 12, fn. 3 (Tlaxcala). The Kiowa witch Tonakat fixed a fireplace in the form of a turtle, the source of his power, and used a meeting once for shamanistic display, being shot with a cartridge and remaining unharmed, etc. A Caddo-Delaware tells of a famous Kiowa doctor who used similar tricks in doctoring a woman. He held a black handkerchief over her to see the location of the disease, dipped a feather in water, cut the skin and removed two ii" bugs, the wound healing immediately. Both popped when thrown into the fire, thus prognosticating her recovery from a twenty years' illness. Wild Horse (Caddo-Delaware) said doctors did "wizard sleight-of-hand tricks" in meetings; "some Indians can make you believe you see things." Some Tonkawa who visited the Kiowa about 1890 performed tricks in meeting like eating fire (Mooney, Peyote Notebook).

25 Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 2:241-42.