COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PLAINS PEYOTISM

| Books - The Peyote Cult |

Drug Abuse

COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PLAINS PEYOTISM

We have now compared the basic Plains rite with that of Mexico and the transitional Lipan-Mescalero. Yet an independent development of this basic rite in the Plains and a multiform flowering of the cult there, influenced by older cultural concepts of a different nature, necessitates a discussion of more minute variants within the region. In other words, we have determined in the previous section the major variations of the peyote ceremony as aboriginally constituted, and now trace the fate of the cult as it invaded a different cul-tural terrain and came under the influence of other culture patterns, including the Christian.' Trip for Peyote. A typical nine-day trip was made by the Cheyenne in 1914 from Wa-tonga, Oklahoma, to Laredo, Texas. Ten "peyote boys" contributed the total cost of $61.85, and several suitcases full of buttons were brought back (about 1,400 each); these were bought from a White dealer in Laredo.2 Another time a Southern Cheyenne, then Presi-dent of the Native American Church, brought back a special trailer full of peyote from Romer, Texas. The northern Plains tribes make infrequent pilgrimages for the plant, de-pending largely upon supplies shipped from Texas or bought from Indians nearer the source. One Wichita leader sold 4o acres of land to buy a car in which to make a trip to Mousquis, his fourth or fifth such trip in about ten years. An early Comanche party going for peyote in the Apache region had much the character of a war journey; as described by Hoebel it involved a clairvoyant discovery of the enemy, prophecy of the outcome, and a horse-raid. Typically, however, the Kickapoo "chip in" money for peyote pilgrimages, and precede this with prayers for the safe-keeping of the travellers.

Rite at Site. The Lipan3 say that

peyote is pretty hard to find when you are looking for it . . . a person who is not used to it doesn't recognize it though he is in the middle of a whole clump of peyote. Once he sees one, another al), pears and so on until they all come out just like stars. If you are having a hard time finding them you do this: when you find just one by itself you eat it. When it takes effect, when you get a little dizzy, you will hear a noise like the wind from a certain direction. Go over there . . . from the place where the noise is coming you will get many peyote plants.

Mrs. Voegelin4 reports an interesting Shawnee concept :

You can get power by visiting the peyote patch in Texas, and telling it at evening that you want help to cure people and get medicine. You sprinkle tobacco there. The next morning, when the Morning Star comes up, the person goes to the patch where he put the tobacco and when he comes close he hears a rattler rattling. If he has nerve enough to go over there, likely he does not find a snake there, but just something to scare him. If he does find a snake there, he grabs the rattlesnake (which is coiled up on top of the medicine) and takes it off and then he picks one peyote button from that place. Then he goes to another bunch and picks another button . . . . Perhaps at the fourth spot where he picks his fourth button, the snake is there again and he must remove it. . . . Jim Clark related this defying of a rattlesnake to the obtaining of another very powerful herb in the old days.'

'The typical Plains gathering ceremony has been described to the writer for the Kiowa, Wichita, and Kickapoo: one sits west of the first peyote found and makes a smoke-prayer before orienting the plant with a thorn or mark that it may be properly used as a "father peyote" later; this first plant shows the gatherer where to find more.

Vowing of Meetings. Spier has traced the pattern of "vowing" the Sun Dance in the Plains and it is interesting to note the persistence of this trait in the peyote ceremony. It is particularly a pattern of the Algonquian-speaking peoples; but we have recorded it for the Kiowa and Wichita as well as the Shawnee, Kickapoo, and Northern Cheyenne.'

Time of Meetings. Peyote meetings are generally held Saturday nights so that the fore-noon of the following Sunday may be spent relaxing and talking under a "shade"; but the Comanche and Seminole sometimes set theirs for Sunday night, following the White pattern for religious meetings.' The Caddo, Tonkawa and Lipan often had four meetings on suc-cessive nights, particularly for sick persons; the Caddo sometimes mark four birthdays with meetings a year apart. Holiday meetings on Easter, New Year's, Thanksgiving and Christmas are common; an Arapaho meeting was once held with a Christmas tree. Many tribes like the Northern Cheyenne drink tea outside meetings, when practising songs or "to sharpen one's mind" when solving some particularly knotty personal problem, but some groups maintain that it is forbidden to use peyote outside meetings, for it would be useless then, even for doctoring. The frequency of meetings throughout the year would be difficult to ascertain, though there is no seasonal restriction as in Mexico; perhaps one or two meetings a month in each tribe might be an average number when the whole year is considered.

Purpose. Doctoring of the sick is the commonest reason given for calling a meeting; but though infrequently expressed as an official motive, the vision-producing physiological effect of peyote is probably the major reason. However, so various are the stated purposes of meetings, that one is led to conclude that when a man wishes to have one, he ordinarily finds little difficulty in discovering a reason for it. A Lipan Apache said,

In the early days they just had a good time for one night. It was not used as a curing ceremony then . . . . At first they wanted to have good visions, that's what they were after. But then, re-cently, they began to use it as a medicine for sick people.8

The Kickapoo and Caddo do not doctor in meetings; the latter pray for the sick, however, and commonly have four meetings in close succession for this purpose, as well as on the first four anniversaries of a child's birth or a man's death.

The primary reason for Northern Cheyenne meetings is social, with doctoring second; they knew of meetings held for rain, but despite prolonged droughts in their region never made them themselves. Comanche formerly held meetings to exercise clairvoyance about the enemies' position, to obtain protection from them' and to ascertain by prophecy the outcome of battle; like the Mescalero they also held meetings to divine and combat sor-cery, and one meeting was held to celebrate the surveying of their lands. Delaware meetings were for the welfare of the community in general, to show hospitality to visiting friends and to mark the first four anniversaries of a death." Kickapoo hold meetings to obtain rain, in consolation for a death, to name a child" and for a dead person."

Mescalero ate peyote to locate the enemy, to find lost objects and to foretell the future as well as for curing." The Osage have funeral meetings, and meetings to "see the face of Jesus" or the faces of their dead relatives ;14 the Oto say they can see the deceased in meetings too. In the Oto Church of the First-born, Jonathan Koshiway baptized, married, and conducted funerals; the Pawnee have no funeral meetings but, celebrate birthdays, New Year's Eve, Christmas and Easter."

A typical Ponca meeting attended at White Eagle was to doctor a sick child with peyote tea. Another, a Shawnee meeting at McCloud, had been vowed if the soldiers' bonus legislation passed Congress. One Shawnee held meetings for his eldest daughter yearly for thirteen years; sometimes they hold purely social meetings and for health and doctoring, but not for rain. Wichita, on the other hand, set up meetings to pray for rain and good crops, on anniversaries, and for doctoring; and a Wichita "bonus" meeting was held in 1936. Proph-ecy has been present in Wichita meetings also. The Winnebago" have death-consolation meetings, death-anniversary meetings and meetings to doctor the sick. At Taos" meetings are for curing, or simply when "someone thinks they ought to have a peyote meeting."

Participants. The Carrizo had two women by the door to bring water into the meeting, but the Lipan permitted no women to be present or even erect the tipi. In the early days the Kiowa, Comanche, Tonkawa, Sauk, and Oto prohibited women from attending, and only old men used peyote, but forty or fifty years ago women started coming in to be doc-tored and gradually came in for other reasons, though they could not use the ritual para-phernalia; under no circumstances may a menstruant woman enter." The restriction against women appears to apply only to groups who early had peyote, when it still had much of the flavor of a warriors' society about it; for example, the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Ponca, Kickapoo, Mescalero, Shawnee, Taos and Wichita apparently always allowed women to attend." In the Iowa meeting the women formed the outer of two concentric circles, the men the inner, and the former were allowed only two buttons." Women never use eagle feather fans.

Some tribes, like the Caddo, still have a strong objection to the presence of White men in meetings, but other groups do not object to White men as such.2' A number of tribes have a bias against the attendance of Negroes, but this is not the case at least with the Kiowa, Wichita, and Kickapoo.22

Visiting. All Indians, however, of whatever tribe, are wekome in the meetings of all other tribes.23 For example, at a Shavvnee leader's meeting at McCloud there were 12 Kicka-poo, 6 Shawnee, 3 Caddo, 2 Kiowa, 2 Whites, a Wichita, a Seminole, a Sauk-and-Fox, an Oto, a Potawatomi and a Negro—a not untypical aggregate.24 Individual users visit around a great deal in trying to "learn about peyote"; an old Kickapoo user had been in meetings of the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Caddo, Delaware, Wichita, Apache, Kiowa, Osage, Yuchi, Sauk-and-Fox, Oto, Iowa, Shawnee, Comanche, Pawnee and Ponca. Indeed, the very origin legend of peyote indicates a period of beginning inter-tribal contacts, and peyotism in later days became the specific vehicle of inter-tribal friendships, when mutual warfare disappeared.

Place of Meeting. The typical place of meeting for the Plains, as well as Taos, Mescalero, and Lipan, is the tipi. The Arapaho-Winnebago peyote tipi has twelve poles, symbolizing the earth." The Pawnee have special painted tipis for peyote, as in the Ghost Dance; and, like the Pawnee, the Wichita and Winnebago dismantle the tipi immediately at the end of a meeting." The Osage, Quapaw, Omaha, Northern Winnebago and others" have special peyote churches, or "round houses" (really polygonal), and many, like the Taos, hold winter meetings in the home of some member.

But meetings were held elsewhere too in the past. The Carrizo had meetings in the open within a circle of sticks. The first Kiowa meetings took place within a circle of upright poles with canvas stretched around it, open to the sky; Comanche also used simple wind-breaks as do even now the Northern Cheyenne, who sometimes also hold the ceremony on a hill-top in the open.28 The Caddo have held meetings in a canvas-covered subconical "stick house" holding over forty people in two rows; and the Bannock of Idaho, on account of opposition to peyotism, have held meetings in backwoods log-houses—in short, the holding of the meeting in a tipi, while common and typical, is not ritually required.

Bathing. The Lipan customarily washed their hair in yucca suds before a meeting, and perfumed themselves with mint. In the Plains and at Mescalero they take a sweatbath or a bath with water; the Arapaho" plunge once against the current and once with it, then rub themselves with teaxuwinen or waxuwahan and other scented plants. The Osage build a sweat lodge as an integral part of their church, in a direct line east of it. A man in Hominy specializes in giving Osage old-style sweat baths, but some of them somewhat ostentatiously travel to Claremore, a hundred miles away, to take "radium baths" before meetings.

Painting. Face and body painting is recorded for the Arapaho, Comanche, Delaware, Kiowa, Oto, Shawnee, Tonkawa, Wichita and Winnebago, yellow being the commonest color used by the Arapaho and Comanche." A Kiowa story tells of the acquiring of an individual paint design in a vision of a red bird which turned into a man. The Tonkawa even painted the fuzz on the top of the fetish peyote red, according to Opler. Painted stripes symbolize for the Wichita the extent of one's experience with peyote: a beginner paints the part of the hair yellow and puts one blue line on his face, adding up to four finally: "He's supposed to know something then." Both men and women painted for Winnebago meetings."

Clothing and Headdress. Formerly native dress was prescribed for Plains peyote meet-ings, and even now a blanket (in summer a folded sheet) among male communicants and a shawl among female is common—to symbolize affiliation with "blanket Indians." Younger men, otherwise in ordinary White dress, often wear a "peyote-necktie" made of an old-fashioned trade blanket, beaded, and with the selvage-stripes as a design; soft neckerchiefs drawn through rings with "water-bird" and "Morning-Star" designs are also common. The Arapaho" water-woman wears a symbolically painted buckskin dress; men wear special wrist-bands and headdresses of yellow hammer and woodpecker feathers. Carrizo men wore only a loincloth in meetings, not even moccasins; the women attendants wore red blankets, the one to the north with woodpecker feathers and the one to the south with a red flicker feather." Iowa wear Kiowa-Comanche style leggings, the thongs of which are knotted with "red medicine" or mescal beans."

A turban or head-scarf has been observed among the Delaware, Shawnee, Kickapoo, Wichita and Winnebago," but the otterskin cap of the Kiowa and Winnebago is optional. At Taos the variant dress of the "peyote boys" has become a symbol of the strife of the old and the new. The young men who use peyote cut out the seats of their trousers, thus converting them into a G-string and leggings and necessitating a blanket, and let their hair grow in Plains fashion." Among older Osage men the "roached" style of scalp lock was formerly still in vogue, but the younger men who have adopted the peyote religion wear their hair long, parted and braided on each side with ribbons and yarn." Among the Winnebago, on the other hand, the progressivism of the peyote cult demands that long hair be cut, and Crashing Thunder discovered that it was a "shame to wear long hair.""

Ritual Restrictions. Salt may not be eaten on the day that peyote is consumed among the Huichol, Tarahumari, Arapaho, Comanche, Kickapoo, Wichita, etc.; the distributional gaps are more likely gaps in our information than lack of the taboo, which is probably universal at least among the early Plains users of peyote." It is also considered hygenically if not ethically unwise to use peyote in connection with alcoholic drinks; indeed, many insist that the former cures addiction to the latter. The Arapaho" did not bring sharp instruments into a peyote meeting, a taboo elsewhere unreported.

Officials. The "road chief'' is the most important individual in a meeting. Kroeber writes-of the Arapaho leader in a manner which might apply to any Plains leader :4'

The leader of each ceremony is sole director of it. He may . . . base [his ceremony] partly on visions during previous ceremonies. In other cases, he follows ceremonies that he has participated in, changing or adding details to suit his personal ideas. No two ceremonies conducted by different individuals are therefore exactly alike; but the general course of all is quite similar.

We do not agree with Petrullo that the leader is a mere "figurehead." Indeed, as we shall see later, the variation in ceremonies is a function of leadership far more than of tribal affiliation. The leader has full authority to change the ceremony in any way he wishes, and his permission must be asked and secured even in such little matters as leaving the tipi temporarily; even the fireman, his chief assistant, constantly consults with him and re-ceives directions.42

In fact, peyote leadership is a matter bringing much prestige, and in these days is a major means of advancement among one's fellows. John Rave, Albert Hensley, Jonathan Koshiway, Quanah Parker and John Wilson find parallels to a less degree in all peyote leaders, and rare is the man who does not seize the apportunity presented by his authority to introduce some change, however trifling, into the ceremony.43 Each tribe has a limited number of recognized peyote leaders which can be named. The Shawnee, for example, have nine only and the Pawnee have only eight recognized leaders in a population of eight hundred. In the case of the Osage the number of leaders is further limited by the number of permanent "churches" available; Murphy lists eighteen "East Moons" on the reserva-tion and three "West Moons."

Originally the officials in a peyote meeting appear to have been limited to the "road-chief," drummer, and "fire-chief."" The "cedar-chief" is a later development. Among the Winnebago the leader, drummer and cedar-man symbolize respectively the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, and the leader gives the drummer his staff even as God delegated au-thority to Jesus." In the Quapaw "Big Moon" the officials number eight: three firemen north of the door (required since every person must be fanned with feathers every time he reënters the tipi), the leader, drummer and cedar-man west of the altar, and in addition "one good man" at each arm of the altar-crucifix cross-piece.

Economics. On the basis of 3,3oo peyote users in 1922 (and the number has since sub-stantially increased) in the United States alone, it is clear that the cult is of economic significance in a number of ways. The price of peyote from dealers in Laredo, who supply most of the northern Plains and Great Basin users, is from $2.5o to $5.00 a thousand but-tons; it is said that "the inhabitants of the small town of Nuevo Laredo, on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande, derive their livelihood almost exclusively from the peyote trade." Schultes estimates $2o,000 as the annual commercial transactions in.volved north of the Rio Grande.46

The Tarahumari used to combine their peyote journeys with trading and other com-mercial transactions, but the trip was otherwise profitable since peyote itself commanded a good price; Lumholtz says one plant cost a sheep at one time in Tarahumariland, and he himself was asked $io for a dozen plants.47 The Huichol sold part of their harvest sometimes to non-pilgrims.48

In the Plains the sponsor usually meets the expense of a meeting himself, but some groups like the Oto pass around a vessel in the morning for a "free-will offering." At Taos the peyote chief bears the expense, though others may make contributions to help defray the cost. The chief expense at Tarahumari, as elsewhere, is the sacrificial beef. The total cost of a meeting varies considerably, according to the number of persons fed at the secular meal the next day. Meetings that Mooney attended in 1918 cost $1 5, $58 (including a beef costing $35), and $8o respectively, but these amounts seem excessive. The writer has sponsored an average meeting costing only about $15, and Hoebel has supplied "groceries" for meetings at from $6 to $10 only."

Considering their importance and authority, it is not surprising that the peyote chiefs come in for some financial recompense. The Tarahumari peyotero was given a quarter of the slaughtered beef, and one peyote doctor at Narázachic made his entire living by peyote cures. Several Kiowa doctors nearly or completely match this. A Sioux doctor at Taos was given a silk dress of the patient's wife, a belt and $5 cash. Indeed, one of the complaints against Wilson, the Caddo-Delaware peyote messiah, was that he over-exploited the financial opportunities afforded by peyote leadership." Victor Griffin (Quapaw) claims to be the only man authorized by Wilson to make Big Moons, and for the building of a small Quapaw "round house" near Miami, Oklahoma, he and his assistant, Charles Tyner (Quapaw) received $75o. There was and is considerable exchanging of gifts in connection with peyote meetings and inter-tribal visiting; feathers, drum sticks, etc. are common gifts, as well as "father peyotes" which have become heirlooms."

Amount of Peyote Eaten. The minimum number of buttons eaten by each participant is usually four. Several persons claim to have eaten 75 to ioo or more, but the average is nearer a third or a fourth of this." Personal observations tend to confirm Mooney's estimate of 12 to 2o as a night's average consumption; he said that go was the most any Kiowa had ever eaten, and he believed this was possible since the individual was powerfully built —although that number would amount to about a pound and a half. This may be so, but one is skeptical of alleged consumptions of more than 3o or 4o average-sized buttons in the dry form. For the green form we should set the maximum at considerably fewer, perhaps 15 or 20 good,sized plants, which even so is a liberal estimate About 3oo each was the average for two Winnebago meetings, and assuming an ordinary group of 2o communi cants this amounts to only 15 buttons apiece. We should call this a fair estimate of the average for beginners and old users combined in a meeting; before accepting larger esti-mates it should be recalled that there is a certain prestige in eating and retaining large amounts of peyote, a fact which may color statements somewhat. Peyote is also consumed as tea, especially by the old and the sick; in one case 24 discs made 15 cups of tea, and in another 3o made 2 quarts of the infusion. A pneumonia patient drank the latter, one cupful every two hours, to induce perspiration deemed necessary for his cure.

Peyote Paraphernalia in General. Typical Plains peyote paraphernalia includes minimally the leader's satchel, gourd rattle, water drum, drum stick, staff, feathers, eagle wing-bone whistle, corn shucks and loose tobacco, bags for peyote and cedar incense, altar cloth, sage, water bucket and ritual-breakfast containers. The rasp is not used by the Lipan or Mes, calero or in the Plains, and the whistle is recent for the two former. The Lipan previously used a bow struck with a stick in place of the later one-sided tambourine drum; the kettle drum, from Mexico, is still more recent." Mescalero shamans sometimes added the use of pollen, which they used to trace a cross on the father peyote, and like the Tonkawa, occa-sionally served the peyote on woven trays instead of in bags. Taos paraphernalia is standard Plains in type. A common color for Arapaho peyote objects is yellow; Skinner thought the beadwork on Iowa gourds and magpie feather fans indicated a Kiowa or Kiowa-Apache provenience. Among the Delaware and others each devotee has his own gourd rattle, but this (like personal drum sticks and feathers) may not be used until after midnight.54

Staff . From ancient times, and possibly before Columbus, the cane or staff was a symbol of authority in Mexico," and for this reason we should hesitate before labeling this feature of peyote an Hispanicism. Again, Opler equates the staff of the Mescalero shaman (which he holds throughout the ceremony, not passing it around with the drum) with the "old age stick'' held by the singer in the aboriginal girl's puberty rite.

Similar syncretism with older patterns seems to have occurred also in the Plains. The Comanche used a bow for a staff when holding peyote meetings on the war path, but the term naci-htta means literally "resting stick-to walk," according to White Wolf. In the Iowa Red Bean war bundle ceremony, the rattle was held in the left hand [sic] while the bow and arrow were waved in the right as the person sang. The Delaware call the leader's staff "arrow," and so also do the Osage, Quapaw and Oto; the Ponca, on the other hand, call it a "bow." The Kiowa suggest that a bow was formerly used, but the term DO'Deid means "brace-to hold-stick"; it must be of bois d'arc (Maclura pomifera C. K. Schneider), however, and some are nocked at the top and bottom like a bow. The Lipan "cane" was called ilkibenatsi'e or "ram-rod."56

The Shawnee, according to Mrs. Voegelin, called the peyote staff the walking stick of the old, but the red tassel at the top symbolized the head-dress worn with a single feather at the war dance. The t'owayennemö of Taos was held in the left hand "for the strength of life," and the red and white horsehair tufts encircling the top (so Dr. White was told) were there "because the White man is above the Indian." A Delaware staff which Dr. Speck saw contained designs representing a tipi, water, the door of the lodge, the blue sky and fire, symbolized by the colors of the bead-work.

Reinterpretations of the meaning of the staff are common. A Wichita called it the "staff of life." The Iowa staff represents the staff of the Saviour, while the Winnebago variously interpret it as a shepherd's crook and the rod with which Moses smote the rock (in obvious reference to the leader's calling for water in the ceremony). Differences in the staff have even come to symbolize a schism in the Winnebago church: that used by Rave was deco-rated, as elsewhere in the Plains, but Clay used a simple undecorated staff, lacking even feathers, calling attention to the fact that Moses staff was undecorated.57

Gourd Rattles. Rattles made of gourds (Lagenaria spp.) have become universal in the Plains since the spread of peyotism; but the Iowa had a small gourd rattle with beaded handle in their Red Bean war bundle dance, and the peripheral-Plains distribution of this trait in pre-peyote times has been traced elsewhere. Some groups (Delaware, Osage, Ute, etc.) have individual rattles for each participant." A large one seen at Apache, Oklahoma, made by Spotted Crow (Cheyenne) had drawn on it a moon with a fire and a Morning Star in negative, together with the following "Jesus talk :""

Help me 0 Lord

My God 0 save me

According to thy Mercy

0 God my heart is fixed.

I will sing And give praise

Even with my glory.

A Wichita gourd was said by one informant to represent the world or sun; the beads are "people talking" and the bead-work in general is "things on the earth," while the horse-hair tuft dyed red on the top represents the rays of the rising sun. A Delaware gourd of Dr. Speck's has bead-work on its handle symbolizing morning (blue), fire (red) and a row of X X X 's (the songs sun).6°

Drum. The standard peyote drum, already described for the Kiowa, made of a small iron kettle with seven bosses in the lacing, is found also among the Arapaho, Comanche, Iowa, Cheyenne, Lipan, Pawnee, Ute, Shawnee, Kickapoo, etc." The Kickapoo say the seven marbles represent the days of the week, just as the twelve eagle feathers of the fan symbolize the twelve months of the year; the four coals which are dropped into the water of the drum are lightning, the water rain and the drumming itself thunder."

In drumming, the vessel is given an occasional shake to wet the head with the contained water, and the left thumb is used to test the tone and tighten the head: sometimes too the head is sucked or blown upon, so that the water is forced to ooze through the skin. The Ponca, however, do not permit the drum head to be touched—"peyote makes the sound, not the hand,"" tlaey say—and hence make a handle of the lacing-rope twisted upon itself.

Old Man Sack (Caddo) also forbade blowing on the drum, "even when it cups up and sounds like a tin can," a Kiowa peyote-boy said; in the stricter Caddo moons no water is drunk until the drum has made four rounds, with the result that some of their meetings consequently last well into the forenoon of the next day—a genuine ordeal according to informants. Among the Iowa, and possibly also in some Caddo Delaware "Big Moons" the drum chief accompanies the drum around the circle, drumming for each singer. The Jesse Clay style of drumming among the Winnebago, described by Densmore, is common among the southern tribes: a rapid unaccented beating before the beginning of the singing, gradually slackening to match the speed of the voice. Another mannerism may be noted at the end of each song, when the rattle is shaken unrhythmically as fast as possible during the last few bars of the song, then suddenly stopped with the last drum beat." The water drum is typically Southeastern in distribution, but its presence in the Plains peyote cult must be accounted another Southwestern feature, inasmuch as it was standardized and diffused over the Plains before Southeastern groups in Oklahoma received peyote and hence could have introduced the trait into it.65

Feathers. Feathers are important in peyote symbolism. In the original Comanche rite only the leader brought in a medicine fan with him; "now many young men bring them who have no special business to." Skinner wrote that eagle feathers were "badges of the society" among peyote,using Iowa; women were never allowed to use eagle feathers in meetings, however. Younger Oto men carry modern ribbed folding-fans, older ones com-monly an entire wing. The individual fans of the Northern Cheyenne, as elsewhere, are not produced until the full effects of the peyote come on, some time after midnight. The eagle feather fans of the Winnebago represent the wings of birds mentioned in Revelations, while the Kickapoo state that the twelve feathers of the eagle fan symbolize the twelve months of the year; twelve is a common Delaware ritual number also."

The Arapaho hang bunches of feathers on the northeast, northwest, southeast and southwest tipi poles to brush off the bodies of tired worshippers. The Mescalero use eagle feathers as a spoon to feed their first peyote to neophytes. The Winnebago, like other tribes, pass a feather around with the staff in its circuit. The Kiowa, Ponca and others use feathers in the water rites: the former make a cross in the midnight water with the feathers of all present, held in a bunch, while the latter place a single feather across the top of the bucket and whistle along the feather. The use of feathers among the Ponca, where cedar incensing is not a strong trait, is especially conspicuous: a feather is passed to the fireman as a symbol of authority, allowing him to leave the tipi without express permission each time from the "road-man," and there is a "baptism" with feathers in the water ceremonies too. The vanes of Ponca feathers are often notched. The red blankets of the two Carrizo women helpers were fastened with a woodpecker and a flicker feather respectively."

Feathers are common in visions too. A Kiowa envisaged his barred hawk-feathers as a ladder rising through the smoke hole of the tipi to heaven, like a Jacob's Ladder, and an-other time as rippling water. Feathers are commonly arranged and cut, colored and tufted, etc., in accordance with visions seen during meetings." Jonathan Koshiway (Oto) had assembled a favorite fan from individual gift feathers, each of which had a different history —one from an old Osage woman who wished for him her long life, two from Hunting-horse (Kiowa), and the like. An interesting development in the Big Moon ceremony is the ritual necessity for each person to be fanned at the fire by the fireman or others every time he re-enters the tipi. This trait is Delaware, Caddo, Osage and Quapaw" in distribution, the latter having two special "guards" at the north and south arms of the altar cross who are charged with fanning each entrant; ordinary incensing with cedar has been reported even among the Ute and is probably universal in peyotism. Perhaps with the same purpose in mind, protection from dangerous influences, the Mescalero takes an eagle feather from either side of the door as he makes his exit, returning as soon as possible."

Birds. We have already noted the importance of birds in Huichol and Tarahumari peyote symbolism, and are to discover that they are equally significant in the Plains. Here the "water-bird" somewhat ambiguously suggests a bird that lives in the water or the bird involved with the whistling for the midnight water. Arapaho songs refer to peyote and the birds which are its messengers, and sparrow hawk, yellow hammer and other woodpecker feathers are common in their meetings. When the fireman goes to get the water he carries an eagle wing, and the whistling which he makes is said to imitate the cry of a bird in search of water (the end of the eagle wing-bone whistle is finally dipped into the water bucket, as though it were the bird drinking)."

The Comanche peyote bird is the "sun-eagle," said to be just under the rising morning sun; "Comanches always mention that bird in their meeting." This bird, the lovina-6hap (literally, "eagle-yellow"), which is represented in the shaped ashes west of the peyote fire, "flashes like the sun; . . . water bird feathers are used just because they are pretty." In this connection it is interesting to recall the Tarahumari place name Couwipigöchi, "place of the wapieri," from the name of a fishing bird, "a cross between an eagle and a hawk, with feet like an eagle," which the Mexicans call aquillala, and the brilliantly colored macao and other birds belonging to the Huichol "Grandfather Fire."'"

The Kiowa represent their "water-bird" on peyote tie-slides as a long-necked bird like a kingfisher or crane; these have been traded all over the Plains. If a Kiowa peyote-user sees an eagle in a vision, he thereafter carries his eagle-feather fan in his left hand as a sign of this." The peyote bird is prominent in symbolic Kiowa paintings also. Jonathan Koshiway, the Oto peyote teacher, said:

The peyote spirit is like a little humming bird. When you are quiet and nothing is disturbing it, it will come to a flower and get the sweet flavor. But if it is disturbed, it goes quick.

Hence the admonitions to sit quietly in meetings and "study" to see if you can "maybe learn something." Tom Panther, a Shawnee leader, called the ash-bird

a holy bird; it drinks as well as we do of the holy water [i.e. some of the ritual water is poured on the ash,figure in the morning] and it gets alive a little when people drink, and from then on is lively until morning.

The martin is said to be the Shawnee peyote bird, as indicated perhaps in the "scissors-tail" shape of some ashes. A Mexican who had long lived with the Wichita had an interesting vision during the water-ceremonies of an Arapaho meeting, when he saw a white feather of the leader "turn into Christ and boss the bald,eagle feather of the fireman around." The association of birds with peyotism, therefore, appears to be universal in the Plains and Mexico alike.

Fetish Peyote. Peyote is the only plant toward which the Kiowa and other typical non-agricultural Plains tribes have a religious attitude and from which they can get "power." Yet the fetishistic attitude as a psychological phenomenon is not unknown in the Plains of pre-peyote times; the Kiowa taime or Sun Dance image and the "Ten-Medicine" bundles have widespread parallels in the Plains—the Cheyenne fetish-arrows and sacred heart, the Iowa red bean war-bundles, and the ubiquitous medicine-bundles of which the Blackfoot are a type." The Arapaho wore the fetish-plant in an amulet pouch covered with beads, and when placed on the altar a head-plume was sometiraes put nearby. The Cheyenne also carry exceptionally large specimens in beaded buckskin cases,"

the beadwork being in the form of a star to represent the sun [?] and the case being suspended from his neck by four strands of beads "to represent the four thoughts that lead to peyote."

A Wichita informant carried a peyote button with him to France in the late War, and the fetish miraculously escaped detection during the sterilizing of uniforms; it protected him until he could return to collect his soldier's bonus in 1936, when a special meeting was held to thank peyote for these boons.

Some Shawnee call the hogim6, or "peyote chief ' the messenger between humans and God; others call it the "interpreter" or the Holy Ghost. Crashing Thunder addressed the most holy peyote medicine as "grandfather," but the usual designation of the fetish is peyote chief" or "father peyote." While Wolf (Comanche) called it "elder brother" because as a child one specific plant had protected him during an illness.

The Winnebago are evidently influenced by an older tribal pattern in their use of two sacred peyotes, one "male" and the other "female." John Wilson in an early Caddo meeting near Fort Cobb, Oklahoma, "before the country opened," placed three peyote buttons on the moon (symbolizing the Trinity of leaders?) ; his drummer saw one of these turn into a person he had known in life. The Lipan usually had only one hucdjiya'isia, or "big peyote lying," but sometimes put buttons in a circle around the fire pit, somewhat like the Comanche who placed them in the sage crescent west of the fire."

The Osage, with their usual flair for ostentation, place the "chief peyote" "within the marked outline of a heart and set upon a beaded cylinder support," according to Dr. Speck. Iowa father peyotes are notable for their size. The Tonkawa sometimes painted the fuzz on the plant red, as though it were a person. The Taos addressed the peyote chief as "Father Ear," probably carrying over to peyote a common Pueblo fetishistic attitude toward corn. Lipan and Mescalero father peyotes were an active ally of the shaman leading the meeting, as any attempt at witchcraft would "show" on it and inform him of something amiss."

Some individuals particularly cherish and prize their "father peyotes." A well-known Wichita leader showed the writer his private collection of them one forenoon after a meeting." Some famous "peyote chiefs" are almost heirlooms. Belo Kozad, a prominent Kiowa peyote leader, has one which once belonged to the famous Comanche chieftain, Quanah Parker. This was passed around at the end of the meeting and handled with the utmost reverence.79

Bible. Peyote-users have also taken over the typical Protestant fetishism of the Bible, but this Christian element in peyote meetings is confined exclusively to Siouan-speaking groups. Radin states categorically that "the use of the Bible is an entirely new element introduced by the Winnebago," but there is good reason to believe that Hensley borrowed this trait from more southerly Oklahoma groups which he visited in the early days of Winnebago peyotism. The Omaha placing of an open Bible near the father peyote may indeed have been influenced by the Winnebago (who put the peyote directly on the open book), and so too the Iowa, but the Oto use of the Bible in the Church of the First-born probably preceded it in Oklahoma, where, indeed, John Wilson's Big Moon cult embodied Christian elements. Further, the reading of the Bible is a feature of the Rave rite only, not of the Clay version, a more aboriginal form."

The Winnebago use the New Testament, especially Revelations. Hensley used to have the singing stop at intervals, so that the younger educated men might translate and interpret portions for non-reading members. For some individuals at least, the Bible was the touchstone of behavior:

Then we went home [says Crashing Thunder] and they showed me a passage in the Bible where it said that it was a shame for any man to wear long hair. I looked at the passage. I was not a man learned in books, but I wanted to give them the impression that I knew how to read so I told them to cut my hair. I was still wearing it long at the time. After my hair was cut I took out a lot of medicines, many small bundles of them. These and my shorn hair I gave to my brother-in-law. Then I cried and my brother-in-law also cried. He thanked rne, told me that I understood and that I had done Well.

Another time, in a peyote vision, his body deserted Crashing Thunder and turned the leaves of the Bible until it came to Matthew 16 and read81 that "Peter did not give himself up''; this meant that the peyote was troubling him because he was stubborn and would not acquiesce to its power.82

The Bible was also used to support rationalizations after the fact :83

At first our meetings were started without following any rule laid down by the Bible, but after-wards we found a very good reason for holding our meetings at night. We searched the Bible and asked many ministers for any evidence of Christ's ever having held any meetings in the day-time but we could find nothing to that effect. We did, however, find evidence that he had been out all night in prayer. As it is our desire to follow as closely as we can in the footsteps of Christ, we hold our meetings at night.

The Bible is said to mention peyote in several places:

And they shall eat the flesh in that night, roast with fire, and unleavened bread; and with bitter herbs they shall eat it (Exodus 12.8).

And this day shall be unto you for a memorial; and ye shall keep it as a feast by an ordinance forever (Exodus '2.14).

Mrs. Voegelin cites a Shawnee belief in a Bible reference to peyote, but it is somewhat ambiguous and obscure."

Altars or "Moons.- Peyote altars range in complexity from the simple war-shield of a Comanche war-party leader on which the peyote was laid, to the elaborate permanent symbolic concrete altars in the Big Moon round-house churches. All the Plains variants are built on the standard crescent altar, grooved from tip to tip by the "peyote road" which devotees must follow to a knowledge of peyote.85 Interpretations of the moon symbolism are almost as numerous as individual users; for, given the physiological effects of peyote and the acceptance in Plains culture of the individual vision "authority,- stand-ardized meanings are not to be expected. One Shawnee, for instance, said the mound rep-resented the mountain of the origin story where "Peyote Woman'' first found peyote; another that the place of the peyote on the moon represented the space between Jesus Christ's eyes, just over the brain, and the arms of the crescent his arms as he lay face downward on the cross: "If we eat the peyote which is on his brain, maybe it will make us think too."

Again, given these factors and the nature of peyote leadership, it is not surprising to find variations run riot; sometimes even the same leader does not conduct two meetings exactly alike, or construct the moon precisely the same (changing the ashes, etc.) Three Osage leaders, for example, change the tribal altar by simply turning everything through 18o° to make a "West Moon." John Elcare (Delaware) is said to have a unique "fish moon,'' north of the fire and facing east, which he feeds and gives to drink. The Omaha" dug a heart-shaped fireplace eight to twelve inches deep to represent the heart of Jesus. We were unable to discover the exact nature of Leonard Taylor's (Cheyenne) "Heart Moon,- no longer conducted, but it appears rather to resemble a Winnebago altar figured by Densmore: a heart superimposed on a cross in the fireplace, under the fire, with a small mound to the east representing the earth.

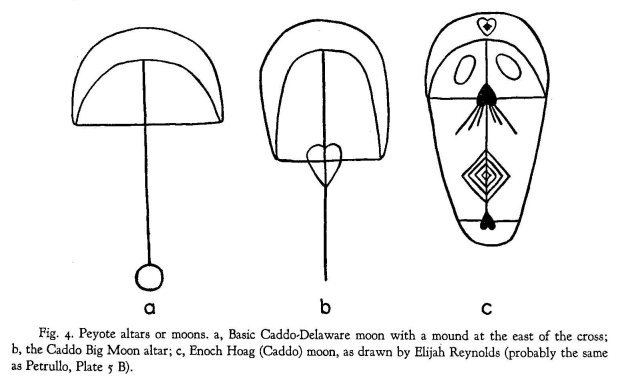

This mound opposite and to the east of the crescent appears to be of Caddoan origin." Jimmy Hunter's moon shows this in perhaps its earliest, and certainly its simplest form: a line joining the mound and the center of the crescent, with another crossing this from hom to hom of the crescent. Bob Dunlap's moon has a further minor addition, a heart at the juncture of the crossed lines. The moon of Ernest Spybuck, pictured in Harrington, is Shawnee rather than Delaware,Caddo, but shows definite Big Moon influence; it is inter-mediate in complexity, perhaps, between the Caddoan small moons and the elaborately symbolic John Wilson Big Moon. The Enoch Hoag moon" (a favorite among the Caddo nowadays) shows features parallel with the Wilson moon: it has a star and a heart at the hair-parting or forehead of the altar "face," ash mounds simulating eyes, an inverted heart at the crossing of the altar-lines as a nose, four concentric lozenges for an oracular mouth, and another heart east of this resembling a cleft chin; the moon itself is the figure's hair. Moonhead's (i.e. John Wilson's) altar similarly represents a man's head, and contains the leader's initials or "foot-prints" and his "grave" alongside that of Jesus. The Black Wolf moon is another elaboration of the Big Moon type.

It must not be thought, however, that the bold innovations begun by John Wilson and others have resulted in a complete chaos of individualism. It requires considerable prestige and force of personality to vision a moon impressively enough to gain an adequate follow, ing. In recent years leaders in the Native American Church have expressed themselves un, favorably on the growing variety and profusion of rival moons, and have urged a return to the standardized simplicity of the older more deeply entrenched forms. Perhaps for this reason, and personality factors as well, several new "moons" have been considerably less than complete successes. A case in point is that of Albert Stamp (Seminole). His design is not strikingly original or different from the moons of the Caddo among whom he lives: he has six concentric lozenges to Hoag's four and has added three concentric triangles. That is all. But his moon has not found acceptance, and he has dismantled his cement altar, removing the entire central symbolic portion, leaving only the crescent and simple polyg-onal apron."

This is only a single instance of a general movement back to more "pure" original forms, stimulated perhaps by the standardizing influence of the Native American Church. This sentiment has had its effect even upon followers of the Wilson Big Moon rite, which is apparently dying out among the Caddo-Delaware (though still strong among the Osage and Quapaw), in favor of the "more Caddo" Hoag moon. If a generalization might be made about the influence of the three tribes most important in the diffusion of Plains peyotism—the Kiowa, the Comanche and the Caddo (who because of their southerly position first received the new religion)"—we might call the Kiowa the original standardizers and teachers, who have departed only in the most minute ways from earlier forms; the Co-manche the proselytizers and missionaries of the new religion; and the Caddo"- the innovators.

Fire. Nowhere is the kind of wood for the fire ritually prescribed. Mulberry, slippery elm, cottonwood and black jack are said not to be good because they pop and give off sparks, tending to scatter the carefully piled,up ashes. Red bud, which gives off much light and little heat, is a favorite for summer use, while box alder is considered good for winter. But "Grandfather Fire" (as the Delaware, Winnebago, Kickapoo and Shawnee address it) is built in a ritually prescribed way, like the angle of a worm-fence with the apex to the west. The Shawnee say the first four sticks represent tipi poles. The ritual number of peyotism, seven, appears in the number of sticks prescribed for the Northern Cheyenne and Taos."

The fire stick at a Kickapoo-Shawnee meeting attended near McCloud, Oklahoma, was elaborately carved with a crescent, a bird, a father peyote on a rosette, the word "Christ" and crossed sticks." The Caddo say this fire stick is the "heart,'' while the twelve interlac, ing sticks of the fire are the "ribs" and the two ash mounds the "lungs" of Jesus; in some Caddo moons two fireman put sticks on alternately." The Wilson moon of the Quapaw and Delaware has three firemen who sit by the door to fan entrants. The Arapaho" leader chooses his hictänälitcä or "fire chief" by silently pointing an eagle wing-feather at him, which the latter uses as a fan during the ceremony; the feather of the Ponca fireman is a symbol of authority. The ceremonial fire as a trait is Mexican, Southwestern, Southeastern and southern Plains (e.g., Caddo and Hasinai), but as involved in peyotism it is a Mexican-Southwestern borrowing rather than Southeastern."

Ashes. An interesting feature, remotely suggesting the Southwest, is the building up of the ashes of the peyote fire into a figure. The commonest form is a crescent, smaller than and parallel to the crescent of the earthen moon, which is nearly universal in the Plains. At an early date the Comanche began making the ashes into the shape of a "sun eagle" and the Kiowa into a "hummingbird." The Shawnee and Kickapoo call it a "water bird"; one Shawnee leader occasionally makes buffalo heads. A Pawnee leader, Good Sun, makes an "eagle" in the ashes. Jonathan Koshiway (Oto) says the bird is "the holy spirit when Jesus was baptized; it's got good eyes like an eagle—you can't fool it.""

The separation of the ashes into two piles in the Big Moon rite comes in for similarly varying interpretations. A Delaware informant said that on one's journey in life toward the peyote "if you're the right kind of fellow you can pass the fire and everything opens up" like the Red Sea. Some say the two ash piles are the lungs of Jesus; others that one is the grave of John Wilson and the other the grave of Jesus Christ. Some Osage say the whole interior of the altar represents a grave.

Smoking. Most of the variations in this ceremony are rather minor. In some groups like the Kiowa only the leader or an older man prays; in others like the Oto all pray aloud at the same time with individual prayers. The Kickapoo ask permission of the leader to make a smoke prayer. The Caddo stop the singing while a prayer is going on, but this is not universal elsewhere. The rule not to pass a smoker or a person chewing peyote appears everywhere, save in the Wilson rite; in this only the leader smoked, and "show-offs" who made requests for tobacco were frowned upon. This descriptive fact is minuscule in im-portance, save in pointing out the authority of the leader and personality traits of Wilson himself. The original ceremony, as indicated by the Lipan, was a communal smoke at the beginning. The Osage are said to smoke cigars in their peyote meetings, but the usual insistence is on native materials, the corn shuck or, occasionally, the oak leaf cigarette.98

In view of the nearly universal ritual use of tobacco in the Americas, the negative cases which occur are interesting. This is traceable to the influence of White Protestantism of the "Russellite" sect in Kansas upon the founder of the Church of the First-born, Jonathan Koshiway. Persuaded by the Kiowa, however, Koshiway and the Oto later abandoned this prohibition, but meanwhile it had spread to other groups. The Iowa" "threw away" smok-ing along with liquor, and did not smoke in peyote meetings. The conjectured Oto origin of Winnebago peyotism is seemingly confirmed by their rejection of smoking in the Jesse Clay meetings:too

My elder brother [says Crashing Thunder upon conversion to peyote] hereafter I shall only regard Earthmaker as holy. I will make no more offerings of tobacco. I will not use any more tobacco. I will not smoke, nor will I chew tobacco. I have no further interest in these things.

The non-use of tobacco in peyote meetings appears to be Pawnee"' as well. Nowadays, as though in compensation for his earlier defection from the pure native rite, Koshiway uses extraordinarily long six-inch corn shucks.

Sage. Sagebrush is used in several ways in peyote meetings: around the periphery of the tipi as a seat, in a cross or rosette under the father peyote on the altar, and in the perfuming ceremony before eating peyote, when it is rubbed between the palms, smelled and rubbed over the head and arms, body and legs.'" Sometimes a bunch of sage tied to-gether is passed around with the singing-staff also.'" Dr. Parsons says that at Taos"' the perfuming is done "to keep the smell of it [on us] so we won't feel weak or dizzy-; and as a similar protective function of sage is reported by Opler for the Lipan and the "Sun Dance weed" by Mrs. Cooke for the Ute, it is evidently wide-spread. The Ute sometimes place a willow rope around the tipi, about four feet in from its circumference.

Passing of Objects. The standard clockwise circuit of tobacco, sage, peyote, para-phernalia, water, food and persons has already been described. This trivial ritual has never-theless been made the vehicle of expression of the leader's authority to change it. Some-times the circuit begins at the door (Lipan), sometimes at the leader or cedar chief (Iowa), and elsewhere smokes may begin at the leader but food and water at the southeast.1" In the morning after the untying of the drum the ritual paraphernalia and the father peyote are commonly passed around for participants to handle (Kickapoo, Kiowa, Ponca, etc.) The Ponca make a point of passing the water between the fire and the paraphernalia at the altar-cloth in the midnight ceremony.

The obsessive, involutional quality of ritualism is nowhere better illustrated than in the minutiae of these rules for passing. We have particularized for the ICiowa the standard modes of passing paraphernalia,1°6 but even experienced "peyote boys" are in need of instruction concerning the "way" of an unfamiliar leader when they visit other tribes. The Northern Cheyenne, for example, may not pass the drum in his clockwise circuit to leave the tipi, save in grave emetgencies when pennission is asked of the leader through the fireman. One may not pass a person praying or smoking or eating peyote, and must again consult the leader to see if the way out is clear; there is still another obstacle in the fireman, for no one may exit between him and his seat while he is fixing the fire (the smoker may temporarily put his smoke on the ground before him, or the fireman temporarily take his seat in these cases).

The Clay rite of the Winnebago has a unique method of passing objects: clockwise along the north from the leader to the fireman at the east, then counter-clockwise back to the leader and around along the south to the door, and again clockwise to the leader. The Caddo meticulously observe another rule in entering and leaving the tipi, as though the interior were divided into north and south sides : those on the south enter clockwise and exit counter-clockwise, while those on the north enter counter-clockwise and exit clock-wise.

These sometimes complicated "rules" are not the least part of "learning about peyote," and the ordering of them by the leader reflects similarly complex psychological transactions among individuals. For instance, the simple matter of leaving the tipi at recesses is involved in schism among the Caddo. Translating the terms, they dte the full-blood Caddo, Enoch Hoag's, as the "systematic way," or "pure tribal way," to which they are currently return-ing (because the leader must be consulted before leaving); the half-Caddo, John Wilson's, is "any kind of way" (because he is said to have abrogated some of these rules). The Seminole, Stamp, attempted a compromise, allowing persons to exit without permission if they observed the rules about not passing in front of a smoker or eater of peyote; "I'm right in the middle," he said. But Elijah Reynolds says, "The older men were skeptical. He just made it up to gain influence among others. It's a kind of racial feeling there."

Praying. Minor variations occur in this procedure too. The Cheyerme are said to pray at great length—"an hour or more sometimes," a Comanche told me. The Oto use cedar in-cense instead of tobacco when they pray. The Ponca pray in unison and audibly before the meeting, seated. The Winnebago stand up together to pray, and the leader stands up to pray with a confessant west of the altar. The Shawnee pray on getting the dirt for the moon," getting the sage, making the mom, putting a cross on it, cutting the com shucks, when the food is brought in, etc. The door-man in Pavvnee meetings makes a special prayer of dismissal. Often, as with the Kiowa and Oto, the "tribal priest" or curator of the tribal palladium is asked to make an official prayer at some time in the meeting. At Taos the chief prays before the line of worshippers enters inside, and all pray inside. Murie says all the Pawnee pray after the closing song, when the sun's first rays strike the altar through the opened door.'"

Mrs. Voegelin gives a typical Shawnee prayer :

My prayer is that of a pitiful man. And also these people here, visitors, I wish my creator to answer my prayer to take pity on those visitors. They came to my daughter's meeting for some good reason to leam something about my daughter's meeting. So each of us give blessing, and bless the water that was brought in this morning. So let our friendship purify it, that we might drink this water, to give us long life, and a better life; and I ask our father to bless all my children, and my wife, and all of us who are in this meeting tonight. I am glad my friends came here to help me with my prayer tonight, my daughter's birthday meeting, and we thank thee for this food she brought in, that our friends who are going to eat this food, that they might feel better from now on in every-day life. We ask in the name of Jesus, Amen. (He then cried ceremonially at the finish of the prayer ; a few tears ran down his cheeks.)

Praying in peyote meetings appears to have much of the psychological flavor of the old vision quest. The speaker's voice becomes louder as he proceeds, earnest and quavering as he sways with the fullness of his emotion and stretches out his hands toward the peyote and the fire. Sometimes his speech is wholly interrupted by uninhibited broken sobbing as he cries out for the pity of the supernaturals. John Rave, the Winnebago teacher, said that "only if you weep and repent will you be able to attain knowledge." Several of the Delaware face-paintings collected by Dr. Speck represent "crying for repentance."

Incense. Cedar incense is invariably placed on the fire at the beginning of the ceremony to purify the paraphernalia and to "bless" the participants before they eat peyote. A pa-tient or one sick from eating peyote is incensed and fanned with an eagle wing, and incense is burnt for the fireman at midnight when he returns with the water, for the leader on re-turning from the whistling ceremony outside, and for the water woman in the morning. Others extend the incensing and fanning to every person who re-enters the tipi after a recess, and the Wilson rite" has special officials to perform this duty. Many leaders about midnight provide for the cedar smoking of personally-owned feathers, drum sticks, gourds, etc., and permit individuals to use their own after midnight until morning in place of the equipment provided by the leader.

Method of Eating. Peyote is most commonly eaten in the raw dried state as "buttons," but when obtainable, in the green form also, which is said to be more potent in action. Sometimes both are provided in the same ceremony, as well as peyote "tea," a dark-brown infusion made of soaked and boiled buttons. For the old and sick the buttons may be soaked and softened in water, or pounded dry in mortars and molded into small moist balls; the latter form is reported for the Arapaho, Caddo, Delaware, Lipan, Osage and Winne-bago. In chewing the dry buttons the Kiowa, Mescalero and others take care to pick off the fuzz on the top lest it cause sore eyes and blindness."9

Singing. The leader always sings the four sets of Esikwita or Mescalero Apache songs as his assistant drums: Hayätinayo (Opening Song), Yahiyano (Midnight Song), Wakaho (Daylight Song) and Gayatina (Closing Song). All the other songs, sung by the partic-ipants during the rounds of the drum, are entirely optional. But the standard set songs are not everywhere used: those of the Ponca are said to be Comanche. The ritual songs of the Pawnee are in the Pawnee language, and those of the John Rave rite are in Winnebago (though the followers of Jesse Clay still use the Apache songs.) The circumstances of the origin of some famous songs by Quanah Parker, John Wilson (e.g., Heyowiniho) and Enoch Hoag (e.g., Yanahiano) are widely known.'"

Many show Christian influence. The Iowa, for example, sing the following songs with Indian vocables, but in a high-pitched style which makes the English words nearly unrec-ognizable:

i. Jesus' way is the only way.

ii. Saviour Jesus is the only Saviour.

iii. Oh, Lord, Lord, Lord! It is not everyone who says that who shall be saved.

iv. I know Jesus now.

v. You must be born again.

The closing song of the Winnebago varies; Yellowbank gave this one:

This is the road that Jesus showed us to walk in.

The followers of Rave close with the Lord's prayer and a song about wings:

There are many wings [repeated five times]

It is God's will that there should be many wings.

The first of these is said to have come from the Arapaho, the second from Isaiah 6. 2, although a New Testament explanation is offered.111 The last song of the Pawnee meeting refers to Christ.112

Other Winnebago songs (with repetitions omitted) are as follows:

God, I thank you for all you have done for me through Jesus' name.

(This is an opening song, according to Yellowbank. Another opening song:)

God's Son says, "Get up and follow Me." Jesus said, "You shall enter into the kindgdom of God."

The following are two morning songs:

Jesus said, "Whoever asks Me for water, I will give him the water of life. If I give him water he will never thirst again.

The sun is coming up now. God made that light for us. We are living now. God made us. To God is the glory.

Other peyote songs are not sung at ritually-set times:

Jesus, how do we know, Jesus, how do we know [him]? We think about Jesus wherever we are.

How did I know, How did I know Jesus?

When I die I will be at the door of heaven and Jesus will take me in.

God said in the beginning, "Let there be light," He meant it for you.

Son of God, have pity on us [repeat]

Son of God, when you come again,

Where your people (the angels) are, let us be.

This is God's way [repeat]

Whosoever believeth in Him will have everlasting life. This is God's way.

We are living humbly on this earth [five times]

Our Heavenly Father, we want everlasting life through Jesus Christ. We are living humbly on this earth.

He is the only way, Christ is the Way of Life,

He is the only aw y.113

Radin"4 adds the following Winnebago songs:

Ask God for life and he will give it to us.

God created us, so pray to him.

To the home of Jesus we are going, pray to him.

Come ye to the road of the son of God; come ye to the road.

Midnight Ceremonies. The whistling outside the tipi at the four quarters is variously rationalized. The Kickapoo say the leader's circuit follows that of the singing inside, the Shawnee that he whistles at the cardinal points "on account of the four different winds." The Northern Cheyenne, according to Hoebel, say they are following the instructions of their culture-hero Sweet Medicine in this, while the Comanche say the whistling is to "notify all things in all directions that we are having a meeting here in the center of the cross, and calling the great power to be with us while we drink so that it could hear our prayers." The Winnebago "flute" blown at this time is to "announce the birth of Christ to all the world"; it also represents the trumpet of the Day of Judgment, and the leader's otter skin hat symbolizes Christ's crown of glory. Other Winnebagol" say the whistling symbolizes the song of praise of the birds in heaven whom God created. The Arapaho say the whistling is an eagle's cry when it is searching for water, and imitates its coming from a great distance until it dips its beak into the water."6

The midnight songs of the Pawnee are said to be for the protection of the man who fetches the water. Old-time Comanche used a paunch for the water, but a bucket is every-where now used; Comanche and Iowa drinking begin at the cedar chief, rather than south of the door as is usual. The Ponca leader dips a feather in the water and sprinkles patients and those nearby with it; and Shawnee sacrifice a cupful to the earth before drinking. The Kickapoo and others drink directly from the bucket when the fireman brings the midnight water, but use a cup when the woman brings the morning water, in graceful symbolism. Some say the woman represents "Peyote Woman"; others, like the Wichita, identify her with older native powers.117

The Lipan have no midnight water ceremony. The Hoag (Caddo) rite has no water ceremonies until the drura has made four rounds of the tipi, but water is brought in for visitors who might call for it or provided outside to be drunk at recesses.u8 In Moonhead's meeting the fireman gets a feather from the leader on leaving and touches the peyote on his return as he is fanned and incensed with cedar.

Recess. After the midnight water ceremony anyone can leave on permission of the leader when he has returned from the whistling ritual outside and been incensed with cedar smoke. People usually leave in twos and threes, as the meeting continues, but they return promptly since others may wish to go out. The Pawnee are apparently unique in their midnight re-cess: after the water ceremony all leave for a ten to twenty-five minute period, the para-phernalia meanwhile resting on the altar cloth.

Doctoring. Doctoring in peyote meetings (save those of the Kickapoo, Caddo and pos.- sibly the Osage)i" is of prime importance, and in a majority of cases is the expressed pm, pose of calling a meeting. The supposed therapeutic virtues of peyote, or in the less tech-nological view, its "power," have been important in the history of the cult. Quanah Parker, the great Comanche proselytizer of peyote, at first opposed to it, was cured of a stomach ailment in 1884 and became one of the most enthusiastic proponents of the herb. Peyote doctoring has been the occasion many times of the spread of peyotism from tribe to tribe (e.g., the Kiowa bringing it to the Creek). Kiowa doctoring was also probably influential in modifying the Church of the First-born on Koshiway's visit in their country, and in bringing it into the fold of the Native American Church.

The motives for the spread of peyotism in the Plains could perhaps be equally divided between doctoring and power-seeking, but the dichotomy is somewhat artificial in terms of native ideologies: indeed, the chief "power" one gets in meetings is for doctoring.120 Winnebago attitudes recorded by Radinizi find parallels elsewhere:

The first and foremost virtue predicated by Rave for the peyote was its curative power. He gives a number of instances in which hopeless venereal diseases and consumption were cured by its use; and this to the present day is the first thing one hears about it. In the early days of the peyote cult it appears that Rave relied principally for new converts upon the knowledge of this great cura-tive virtue of the peyote . . . . Along this line lay unquestionably its appeal for the first converts. Its spread was due to a large number of interacting factors. One informant claims that there was little religion connected with it at first, and that people drank the peyote on account of its peculiar effects.

Densmore122 says that prayer during Winnebago peyote doctoring "are petitions to God for the recovery of the sick person, not affirmations of his recovery.-

Opler quotes a Lipan informant on doctoring:123

In the early days they just had a good time for one night. It was not used as a curing ceremony then . . . . At first they wanted to have good visions, that's what they were after. But then, re-cently, they began to use it as a medicine for sick people . . . . If a sick person comes in the tipi, they see what is the matter with him. Perhaps a witch has shot something into him, a bone or some-thing like that. It is seen. Then the sick one rolls a cigarette and gives it to someone there who he thinks can cure him. Perhaps some man says, "I think I can take that out with the help of peyote and these other men." So he does his ceremonial work in there and extracts what is bothering the patient . . . . He sucks it out usually with his own lips, not with a tube. It is nasty work right there. It might be dirty and full of pus. But the medicine man doesn't think of it in that way. To them it is just as if they were sucking nice juice out of something. Yet it will look terrible to others . . . All the bad things have to go into the fire and burn down to ashes . . . . Sometimes they suck out things like insects which have been shot into people and these things pop. Some-times when they throw the evil object in the fire it blazes up blue but does not pop.

Northern Cheyenne and Shawnee patients sit in special places in the peyote tipi, as in the sweat lodge, suggesting that older patterns of doctoring are involved; as we have seen, the sweat lodge is an integral part of the Osage peyote round-house plan. That asso-ciations of curing by peyote and curing in the sweat lodge lie close to the surface finds affirmation in an interesting Arapaho case:124

One of the recent modifications of the peyote ceremonial was devised by a firm devotee, to cure a sick person. The originator of this new form of the worship believes himself to have been cured by the drug. In this ceremonial, which was repeated four times, the tent seems to have represented a sweat house, and a path led from the entrance to a fire outside, as before a sweat lodge. The ritual, while remaining a peyote ceremony, conformed more or less to the ordinary processes of doctoring a sick person.

One could easily over-emphasize the novelty of such a procedure, considering the wide-spread use of peyote in doctoring, yet even the Caddo, who do not doctor with peyote, often have four meetings to pray for the recovery of the sick person; certainly cures by peyote do not rest entirely on the "technological" procedure of the patient's eating and drinking peyote, but others present "help" by eating in the name of the sufferer and pray-ing. This is not at all unlike the presence of relatives and others in the sweat bath praying for the patient's recovery; the various uses of sage, the fire pits in some altars, and the ritual necessity for a fire even on the hottest summer nights further suggest sweat bath parallels."'

Peyote is a panacea in doctoring. A Cheyenne woman was cured of a cancer of the liver which had been pronounced hopeless at a White hospital. Such invidious distinctions be-tween White and peyote doctoring are common; for the former represents merely human skill, and is not the unmodified herb the direct creation of God? Belo Kozad, himself a well-known Kiowa peyote doctor, spoke as follows:

When my sick wife was in there I chewed peyote for her. Her skin got like wood bark—the hair come out. The doctors couldn't make it. We give it up, can't do anything. [It was] diabetes, and we shoot him every time she eats. That spoils the people; they lose the mind and the skin gets bad. That morphine for Howard [Sankadote, who was ill the night of the meeting and could not be present] make him talk funny. It just ruin the people in the mind. Come to peyote! God knows more than any people!

Perhaps Belo had every "pragmatic" right to talk thus : had he not himself cured a boy's hemorrhage by eating one hundred green peyotes for him? Peyote indeed is a famous cure for tuberculosis and respiratory diseases.

John Bearskin (Winnebago) knew of two cures by "Sister Etta" in meetings: one a woman with goitre, the other a boy who had previously been dumb.'" Pneumonia also readily yields to peyote, producing beneficial perspiration when thirty buttons are drunk over a period of hours in two quarts of water. The writer has seen doctoring with peyote for a crushed thigh, tuberculosis, and malnutrition (?) in a two,year-old child; this last cried fretfully in the early part of the meeting, but was fed "tea" until it was blue and quiet in strychnine tetanus by morning. The wife of our Quapaw host had also been "operated on in church."

A Sioux doctor, who had gotten his power from a vision in which peyote turned into a man, doctored at Taos; but an acquaintance of Dr. Parsons imputed his trachoma to witchcraft on the part of "foreigners" who came to large meetings. He found that peyote water prevented the inflammation of his eyes. Another boy's leg was "all gone, rotten," and the boy himself emaciated. Peyote men prayed over him for a month, whereupon he became well and fat, though his leg remained drawn up because he had taken too much White man's medicine. The wife of a peyote man, herself cured of neck sores by the plant, asserted that witch sickness is lacking nowadays, in Taos because of the power of peyote in exorcizing witchcraft ; a peyote chief, however, holding a button in his hand, had had to remove a porcupine quill which some witch had shot into her nose. At Taos even anti, peyotists consider it good for cures, and Dr. Parsons, no doubt with some reason, makes the query : "Will peyote find its character of witch prophylaxis an introduction to the southern pueblos'?" in

Peyote is equally successful in treating mental cases. An Oto informant told of four suc, cessive meetings held for a man who had "gone crazy" when his wife left him. Formerly under observation at Norman, he was afraid people were coming for him during the meet, ing; he could hardly talk, wanted to run out and people had to wrestle with him. Old Man White Horn gave him a peyote and told him it would protect him; finally, in the third sue, cessive meeting the man "came to" and asked what had been happening. Another Oto patient chopped wood incessantly, rolled and unrolled strings, etc., and used to have "meet, ings" by himself, drumming, singing and eating peyote all alone. An Oto told me of a Taos boy who had "gone crazy"; some said it was peyote that was doing this. But a doctor from west of Albuquerque came and pulled a snake and a dead water dog out of him; these had been his medicines, taught him by his father, and it was decided that he had clearly broken some taboo surrounding his father's medicine.

"Preaching." An interesting feature of peyotism, probably deriving from earlier pat, terns, is the moral lecture in the morning. In one Caddo "moon" the leader "talks to the boys, teaches them, just like a preacher, telling them to do the right thing through life, and the consequences if they didn't do the right things." White Wolf (Comanche) says Quanah Parker lectured younger people in the morning; so too did Kickapoo, Carrizo, Shawnee and Wichita leaders.

After passing peyote, the Delaware leader "addresses the peyote and the fire, prays, and often delivers a regular sermon or moral lecture." In the Iowa meeting:128

The peyote chief . . leads in the preaching and Bible reading . . . . The leader (or, as the writer understands it) perhaps some visiting preacher of the faith, gets up and delivers a sermon, while the cedar chief casts some more incense on the fire. [He commonly exhorts them to confession.] The leader then calls on other preachers to talk, and then asks the fire chief [to pass the peyote again] . . . Meanwhile he continues to read the Bible and exhort all sinners to repent. He points out that all the old ways have been given up, and with them their "idols," such as the great drum of the religious dance.

John Wilson ordinarily began his meetings with a talk by himself; the Oto are commonly addressed in meetings by their "tribal priest." 'The estrangement of the lively J. S. (Kiowa) and his young wife was composed through moral homilies delivered by older relatives in a peyote meeting—a typical occurrence.

At the end of the Pawnee meetine

the members . . . sit in their places and talk over their experiences . . . . The leader closes the meeting at noon with a lecture, or sermon, on ethical matters, speaking especially against the use of alcohol.

Possibly Osage "testimony" may have some relation to this.'" The Winnebago"'

ceremony is opened by a prayer by the founder and leader, this being followed by an introductory speech . . . . During the early hours . . . speeches by people in the audience [are made], and the reading and explanation of part of the Bible.

The midnight sermon, after the midnight water, also occurs:"2

Then the leader asks anyone he desires to make a speech. This may emphasize any point in regard to peyote.

The moral harangue is no doubt derived from earlier Plains patterns, though it is a South, western feature as well, among the Rio Grande Pueblos and elsewhere."'

Prophecy. The gift of prophecy has often been claimed by individuals in native America. The first well-known such was Popé of the Pueblo Revolt in 168o, but his successors were many: Wabokieshiek, or "White Cloud," the Winnebago-Sauk prophet of the Black Hawk War; the Delaware prophet of Pontiac's Conspiracy (1762); Tenskwatawa, twin brother of Tecumseh, and the well-known "Shawnee Prophet" (1805); Kanakuk, the Kickapoola4 reformer (1827); Smohalla, the Sokulk dreamer of the Columbia (187o—x885); Tavibo, the Paiute; Nakaidoklini, the Apache (1880 ; Wovoka, or Jack Wilson, the Paiute prophet of the Ghost Dance of 1889 and later; Skaniadariio, or "Handsome Lake," the Seneca teacher, etc."'

Save for the revelations of the Caddo-Delaware John Wilson, and the teachings of John Rave and Jonathan Koshiway, this tradition has become much attenuated as regards peyotism. Large-scale prophecies can no longer be made to skeptical and disillusioned audit ences, but prophecy in minor matters still occurs via peyote (e.g., the Delaware case in which a serious industrial accident might have been avoided if he had only been able to interpret correctly a warning peyote gave him). Old-time Comanche could hear the enemy while still away off when they ate peyote, and in making raids could discover the where-abouts of horses, etc. White Wolf, again, visioned Charley Seminole's face all bloody at a peyote meeting, but was unable to interpret the prophecy; somewhat later, sure enough, the Seminole accidentally shot himself under the eye.