APPENDIX 7 : JOHN WILSON, THE REVEALER OF PEYOTE

| Books - The Peyote Cult |

Drug Abuse

APPENDIX 7 : JOHN WILSON, THE REVEALER OF PEYOTE

The life and career of a remarkable individual were successively involved in the several traditions of the Ghost Dance, mescalism, old Algonquian shamanistic "shooting" cere, monies and finally peyotism. Both for its intrinsic interest and its historical significance we give here in some detail the life of this man. Wilson appears first as a leader in the Ghost Dance movement of the 189o's. Mooney' writes :

The principal leader of the Ghost dance among the Caddo is NIshldintii, "Moon Head," known to the whites as John Wilson. Although considered a Caddo, and speaking only that language,2 he is very much of a mixture, being half Delaware, one-fourth Caddo, and one-fourth French. One of his grandfathers was a Frenchman. As the Caddo lived originally in Louisiana, there is a consid-erable mixture of French blood among them, which manifests itself in his case in a fairly heavy beard. He is about 5o years of age [in 1892—.93], rather tall and well built, and wears his hair at full length flowing loosely over his shoulders. With a good head and strong, intelligent features, he presents the appearance of a natural leader . . . . He was one of the first Caddo to go into a trance, the occa-sion being the great Ghost dance held by the Arapaho and Cheyenne near Darlington agency, at which Sitting Bull presided, in the fall of 189o. On his return to consciousness he had wonderful things to tell of his experiences in the spirit world, composed a new song, and from that time be-came the high priest of the Caddo dance. Since then his trances have been frequent, both in and out of the Ghost dance, and in addition to his leadership in this connection he assumes the occult powers and authority of a great medicine-man, all the powers claimed by him being freely conceded by his people.

Captain Scott, who visited the Caddo in 1890-91 during the period of their greatest excite, ment about the Ghost Dance, also met Wilson, of whom he writes:8

John Wilson, a Caddo man of much prominence, was especially affected [by the Ghost Dance], performing a series of gyrations that were most remarkable. At all hours of the day and night his cry could be heard all over camp, and when found he would be dancing in the ring, possibly upon one foot, with his eyes closed and the forefinger of his right hand pointed upward, or in some other ridiculous posture. Upon being asked his reasons for assuming these attitudes he replied that he could not help it; that it came over him just like cramps.

Wilson soon became a well,known doctor in this connection. Scott continues:

John Wilson had progressed finely, and was now a full-fledged doctor, a healer of diseases, and a finder of stolen property through supematural means. One day, while we were in the tent, a Wichita woman entered, led by the spirit. It was explained to us that she did not even know who lived there, but some force she could not account for brought her. Having stated her case to John, he went off into a fit of the jerks, in which his spirit went up and saw "his father" (i.e., God), and who directed him how to cure this woman. When he came to, he explained the cure to her, and sent her away rejoicing. Soon afterwards a Keechei man came in, who was blind of one eye, and who desired to have the vision restored. John again consulted his father, who informed him that nothing could be done for that eye because that man held aloof from the dance.

When Mooney visited the Caddo on Sugar Creek late in 1895,

John Wilson came down from his own camp to explain his part in the Ghost dance. He wore a wide-brim hat, with his hair flowing down to his shoulders, and on his breast, suspended from a cord, about his neck, was a curious amulet consisting of the polished end of a buffalo horn, sur, rounded by a circlet of downy red feathers, within another circle of badger and owl claws. He explained that this was the source of his prophetic and clairvoyant inspiration. The buffalo horn was "God's heart," the red feathers contained his own heart,4 and the circle of claws represented the world. When he prayed for help, his heart communed with "God's heart," and he learned what he wished to know. He had much to say also of the moon. Sometimes in his trances he went to the moon and the moon taught him secrets . . . He claimed an intimate acquaintance with the other world and asserted positively that he could tell me "just what heaven is like." Another man who accompanied him had a yellow sun with green rays painted on his forehead, with an elaborate rayed crescent in green, red, and yellow on his chin, and wore a necklace from which depended a crucifix and a brass clockwheel, the latter, as he stated, representing the sun.

On entering the room where I sat awaiting him, NIshkiantii approached and performed mystic passes in front of my face with his hands, after the manner of the hypnotist priests in the Ghost dance, blowing upon me the while, as he afterward explained to blow evil things away from me be, fore beginning to talk on religious subjects. . . .5 Laying one hand on my head, and grasping my own hand with the other, he prayed silently for some time with bowed head, and then lifting his hand from my head, he passed it over my face, down my shoulder and arm to the hand, which he grasped and pressed slightly, and then released the fingers with a graceful upward sweep. 6

A curious mixture of Caddoan (?) mescalism, Ghost Dance, Delaware "shooting" ceremonies and early peyotism occurred among the Shawnee when Wilson came to them about 1889. The Quapaw were being taught the Ghost Dance, in which a small water drum was used to accompany the circling of the dancers, alternately men and women. Wilson showed them how to swallow mescal beans, and also how to "shoot" them into a person so that he or she would fall down. Then he doctored the person with peyote to bring him back to consciousness. A number of tribes were involved in these doings, ac-cording to Mrs. Voegelin, the Shawnee, Delaware, Mohawk, Peoria, Caddo (?), Quapaw, Iowa and Oto. Gradually, however, Wilson turned from the Ghost Dance to peyote. Al-ready in Mooney's time he was "prominent in the mescal [i.e., peyote] rite, which has recently come to his tribe [the Caddo] from the Kiowa and Comanche."'

Both mescalism and the Ghost Dance, in his person, have traceable influence upon peyc ism. This syncretism of cultures in one personality is of considerable interest.

Before Wilson had quite reached the age of forty, he had lived the life of an ordinary Indian of Oklahoma. He was addicted to moderate drinking. He frequented the social dances and gambling gatherings usual among reservation groups of his type. He had participated likewise in the contem-porary religious ceremonies performed by the Delaware. . . . As a vagrant, not however in the condemning sense of the term, he had wandered as most Oklahoma Indians do, from tribe to tribe and inevitably also among the whites experiencing the wide range of personal and social contacts which might be inferred from the statement. Anderson states, in short, that his uncle had lived a sinful life but adds in effect that he had not been guilty of any major offences. He was married to a woman of Delaware and Caddo descent and had an adopted son, Black Wolf, reputed to be also part Delaware part Caddo, and who is still living (1932) and carrying out Wilson's teachings and ministrations.

About this time he attended a Comanche dance, where a Comanche man presented him with a peyote button and told him to give it a trial—which he did in an unusually thorough manner. Speck continues:

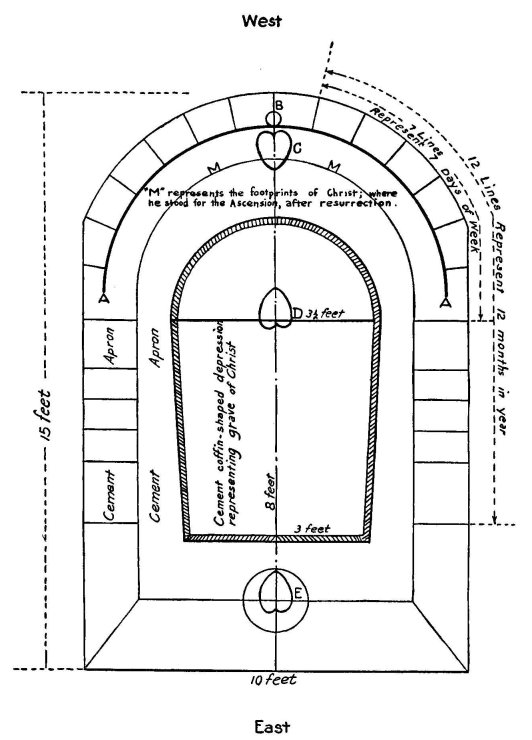

Fig. 6. An Osage altar of the John Wilson Big Moon type. A, "Peyote path," or Moonaead (Wilson's name); B, hole for "arrow" when not in use; C, "Heart of Goodness" where father peyote is placed; D, Heart of the World above which the ritual fire is built ; E, the Sun, giver of life. The east-west line is the "straight road" the way to heaven, or "thinking straight"; the north-south line represents "the road across the world"; together they form a cross symbolic of the crucifixion.

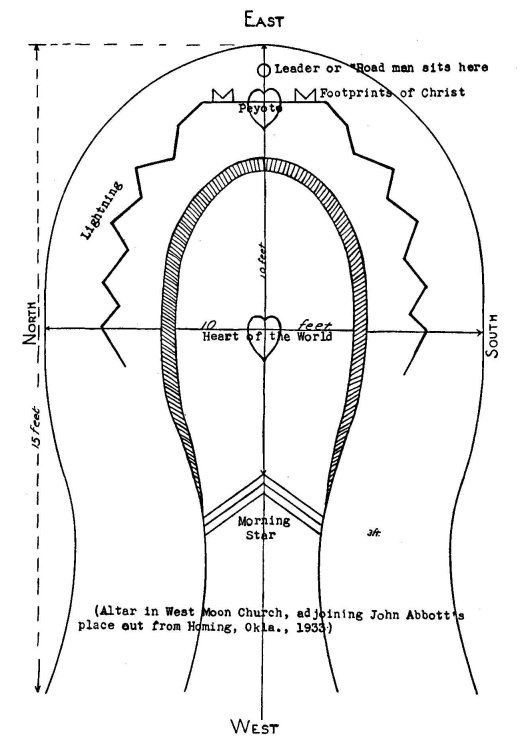

Fig. 7. A variant Osage moon of somewhat esoteric symbolism. This and the Osage moon in Figure 6 are reproduced through the courtesy of Mr. D. F. Murphy.

Before long he concluded to adopt the advice given and to retire from worldly companionship, to make the trial and to study its outcome. With this objective in mind he informed his wife, secured provisions for a few weeks stay in camp and together they drove away in a wagon to a little creek where an abundant supply of fresh drinkable water might be had. The place he selected was a secluded "clean and open place" where they would be alone free from intrusion and worldly dis-tractions. Anderson thinks that Wilson remained there about two or three weeks but he does not remember hearing him say how long. When all was ready he began his innovation to the mysteries of Peyote the first night by eating 8 or 9 "buttons." We learn that during the period of self ex-posure to the power of Peyote he took the medicine at frequent intervals during the day or night as the impulse prompted him using about the same quantity each time it was taken. As soon as he began, using the words of the informant, "Peyote took pity on him" for his humble mien and sincere desire to learn it,s power. During the whole period he allowed nothing to distract him, giving his entire thought and wish to learn what Peyote might teach him. The outcome was the revelation that motivated him for the rest of his life and made him a teacher of the Peyote doctrines, which he himself exclusively evolved through the revelations given him at this time.

During the time of his sojourn, Wilson did not fast or undergo other abnegations but lived normally. . . . Each time Wilson took peyote during those days and nights of seclusion he ate about fifteen peyote "buttons." . . . During the two weeks or so of his experimental seclusion, Wilson was continually translated in spirit to the sky realm where he was conducted by Peyote. In this estate he was shown the figures in the sky and the celestial landmarks which represented the events in the life of Christ, and also the relative positions of the Spiritual Forces, the Moon, Sun, Fire, which had long been known to the Delawares, through native traditional teachings, as Grandfather and Elder Brothers. Here, too, he was shown the grave of Christ, now empty, "where Christ had rolled away the rocks at the door of the grave and risen to the sky." He was shown, always under the guidance of Peyote, the "Road" which led from the grave of Christ to the Moon in the Sky which Christ had taken in his ascent. He was told by Peyote to walk in this path or "Road" for the rest of his life, advancing step by step as his knowledge would increase through the use of peyote, remaining faithful to its teachings . . . [and if he did] he would finally, just before his death, bring him into the actual presence of Christ and of Peyote . . . . The details of construction of the earth works to form the "Moon" which he was to construct in the Peyote tent were all revealed to him with their meanings as Peyote continued his instructions to Wilson during his visits to the sky. . . . Also came revelations as to how the face should be painted, the hair dressed. Of major importance, however, was the complete course of instruction given to Wilson by Peyote in the singing and syllabization of the numerous Peyote songs which were to form the principal parts of the ceremony of worship. Anderson felt certain that Wilson possessed and used no less than two hundred of these songs.'

Wilson's original moon, however, passed through an evolution, for Anderson's drawing in Speck is considerably simpler in design than those depicted for the Osage by Murphy, or photographed by the author for the Quapaw. An early version, apparently, is one collected from Henry Hunt (Wichita) near Anadarko. In this the crescent or "moon" is elongated to imitate the parted hair of an Indian, whose eyes are the two mounds of ashes between its horns; a line runs from the father-peyote to the east, terminating in a mound with five circles concentrically zoning it like a globe-map, with another line at right angles to this drawn from tip to tip of the crescent, making a cross, at the intersection of which is drawn a heart resembling a man's nose. There is also a heart at the "parting" of the hair, on which the fetish peyote rests, and a third one on the top of the zoned mound at the east. This altar is said to symbolize Moonhead's face, and indeed it much resembles one when seen from the eastern door. Speck says in confirmation of our conjecture that

at first, he said, he made a small "Moon," increasing its size day by day symbolical of his progress in spiritual knowledge. By the end of his sojourn amid spiritual environment, he came to make the so-called large "Moon," the Wilson "Moon" which has become typical of his followers.'

But Wilson, no doubt, made still later additions, for these early moons entirely lack the elaborate apron symbolism of the Osage and Quapaw altars.

A Delaware informant said Wilson's moon was first used north of Lookeba, Oklahoma. Black Wolf and George Caddo were early converts to his version—which, indeed may initially have been not so different from the older Caddo moon with a cross and mound east of the crescent (the Wilson division of the tipi into north and south side, for example, is an old one in Caddoan ceremonial organization)." The symbolism of the Wilson "Big Moon" receives varied interpretations nowadays. The Osage call the three hearts of the altar the "Heart of Goodness," the "Heart of the World," and the "Heart of Jesus ;" others interpret the "world" as the "sun." The ashes are the graves of Christ and Wilson for some, the dividing of the Red Sea for others. Some say the whole firepit is the grave of Christ, and the ash mounds his lungs, as the figure under the fire is his heart. The twelve lines of the altar apron are variously the twelve steps to heaven, the twelve heavens of Delaware mythology, the twelve months of the year, the twelve feathers of the eagle's tail, etc. The symbolism of seven for the "days of the week" is possibly Southwestern in origin (cf. the seven bosses of the drum). Diamond-shaped figures close to the sun-mound represent Christ's foot-prints, according to Petrullo," while the "WW" or "MM" at the west of the altar are said to mean this for the Quapaw ("Moonhead" or "Wilson" depending on one's position while reading the initials). The cross of the altar, of course, is symbolical of the Crucifixion. The cigarette of corn husk is known as the "Pipe of Jesus" among the Delaware."

Peyote taught Wilson many variations in the ceremony as well. He used a crock in-stead of a kettle for the peyote drum. At one period in the development of the ritual only the firemen did the drununing besides the leader and his assistant (i.e., four men, three firemen and the leader's assistant, proceeded clockwise around the tipi with the drum, drumming for each singer in turn, instead of the standard method of passing the drum for all to use); Wilson did not require the drum to make four rounds, for this might occasionally have interfered with the morning rite of filing out of the tipi "to meet the sun" with raised arms and prayer. In his rite only the leader made the initial prayer-smoke, though older men might ask for smokes later in the night if they so desired. Cigarettes could be made only at one of four places, one informant stated : at the leader's place, at the north or south at the ends of the cross, and at the fireman's place, and the leader had to smoke all of them first. Upon reentering after a recess, each person was incensed and fanned by the firemen and others to blow away whatever evil influences might cling to him from the outside night. In time Wilson added special functionaries at the cross-bars of the crucifix to perform this fanning, making eight officials: two fanners, three firemen-drummers and three leaders (road man, drummer and cedar man) symbolizing the Father, Son and Holy Ghost of the Christian Trinity. In the Wilson rite there was much touching of the father peyote as communicants made their circuit of the altar on reentering. It is said that water could be asked for at any time, and permission to leave was not necessary if the rules about passing in front of an eater or smoker were observed.

Wilson himself took his "moon" to the tribes of northeastern Oklahoma. The Shawnee were influenced impermanently, and today only Ernest Spybuck has a modified Big Moon. The Seneca were influenced through the Quapaw, whom Wilson first succeeded in deeply influencing. The Quapaw leader, Victor Griffin, made a moon at Devil's Promenade which was modified around 1906 or 1907 from Wilson's moon." The Delaware around Dewey were much influenced by Wilson from 189o-9z on." But the Osage were the most important converts. By 1902 "most of the Indians at the Hominy camp and elsewhere in the Nation [had] taken it up and become devoted to it."'5 Black Dog, one of the first Osage converts, introduced the "West Moon" in which the door is at the west and the altar similarly reversed; most of the Osage moons today, however, are the standard Clermont east moons. The Potawatomi may have been influenced by the teachings of Wilson somewhat also." Wilson's nephew, Anderson, brought the Seneca peyote in 19°7 on the request of a Seneca married to a Quapaw woman."

The economic motive seems evident in much of Wilson's behavior. Speck tells of the introduction of peyote among the Osage as follows:"

[About 1891] John Wilson was on his way from Anadarko to conduct meetings among the Delawares around Copan. While passing through the Osage nation he visited Tall Chief, a Quapaw married to an Osage woman. While here Wilson was stopped by an Osage who had previously attended Peyote meetings among the Delawares and requested to meet a group of Osage and tell them about his revelations and his convictions and instruct them in its rules. He consented and complied with their wishes. The Osage in attendance at his meeting were convinced and converted. He accordingly stayed on with them about three weeks. Black Dog was at the time Chief of the Osage. His tribe was won over in force to the Wilson sect of Peyote worshippers. . . . J. Wilson then returned to Anadarko, leaving behind him among the Osage two young Delawares who stayed back attracted by the prospects of fortune offered by the wealthy Osage. Wilson had received pres-ents from the tribe of new converts amounting to considerable value, a wagon, a carriage, a buggy and teams of good horses and harness for each and other horses, fourteen in all, not to mention blankets, goods and money.

His death occurred after a similar mission to the Quapaw. He had been among them to conduct a meeting and was returning to Anadarko in a buggy with a Quapaw woman and another woman. Wilson's wife was still living at the time, and he was either offered the Quapaw woman or demanded her while among the tribe. Speck quotes his nephew :1°

Anderson said he did not like to think this but that the Quapaw were not all good people and had possibly been actuated by a desire to establish a home for Wilson in order to keep him and his ministry in their midst.

In any event, Wilson had been given a number of horses, which were tied to the back of his buggy. While crossing a railroad track, these horses pulled back and prevented their crossing just as a locomotive bore down upon them. Wilson was instantly killed. His detractors maintain that this was just punishment for his failure to live up to his own teachings. Since this period many communicants have fallen away from his "moon," for his own 20

moral instructions . . . referred to abstinence from liquor, to restraint [in] sexual matters and fidelity to matrimony.

Though influenced by Catholic teachings, Wilson had a peculiar and specific attitude toward the Bible.2' According to Speck,22 he

instructed the Indians to seek knowledge by direct communion and to avoid consulting the Bible or the Gospels for the purpose of moral instructions. He insisted that the Bible was intended for the white man who had been guilty of the crucifixion of Christ and that the Indian who had not been a party to the deed was exempt from guilt on this score and that therefore, the Indian was to re-ceive his religious influences directly and in person from God through the Peyote Spirit, whereas Christ was sent for this mission to the white man.

He nevertheless embodied in his person many of the messianic characteristics of his several native prophet predecessors; a Delaware informant said "John Wilson used to perform miracles" in meetings, such as divining what was in a man's mind, and telling him who the persons were that he saw in a vision. The Osage, at least formerly, had a marked reverence for Wilson. Speck wrote in 1907 that (23) pictures of Wilson are in demand among the devotees, who kiss them on sight. The man has been deified since his death.

There is much variation of opinion about Wilson among Indians of various tribes, but perhaps the statements of his nephew, George Anderson, are authoritative if not entirely disinterested. Speck says:24

An idea seems to have become current, either through the rumors of designing persons who opposed him or through exaggeration among his followers, that Wilson is responsible for having told his associates that he would return to life again after death and also that they should pray to him in the Peyote meetings . ... Anderson denies that Wilson made either assertion. He had heard Wilson tell in his meetings that at times the worshippers when taking peyote might see him, as some are said since to have done, his face appearing to their vision over the fire. [With reference to the second statement Wilson on the contrary warned them not to pray to him, but through peyote to God.] .... This warning has not, however, prevented the practice of praying directly to and through John Wilson from becoming frequent among some of the Osages . . . and probably among the Quapaw.

In both the latter groups [Anderson] has seen Wilson's portrait placed on the "moon" in the Peyote lodge near the peyote "button" and the crucifix. Some who do this, he is convinced, ac-tually concentrate thought upon Wilson instead of Peyote. And Anderson regards both practices as contrary to the teachings of Wilson. A custom has also spread among the Osage to wear a por-trait button of John Wilson on the coat or, when in native dress, upon one of the fur or feather ornaments . . . Anderson's testimony [was] that John Wilson told his followers that he was not sent by God to fulfill a mission, but that he was shown by Peyote how to conduct religious worship in the Peyote meetings in order to cure disease, heal injury, purge the body from the effects of sin26 and to lead the Indians to reach the regions "above" hukweyun in Delaware, or heaven, where they would see Peyote and the Creator.

The Caddo and Delaware, nevertheless, display considerable "touchiness" on the subject of John Wilson even today, since other tribes have ridiculed his real or supposed claims to divinity. Native criticism is not lacking either on the score of his economic exploitation of peyote leadership." Petrullo27 writes that his enemies claim that in the course of his life he professed to have had fresh visions which always were interpreted to his personal gain

However, his followers staunchly deny these allegations. Perhaps in answer to the accusa-tion of being mercenary, Wilson, with one of his followers named Wolf, themselves set up a meeting once, at which they showed their generosity by giving away all their clothes with other gifts until they were clad only in breechclouts. 28 Yet even so the belief is widespread that his death was due to his exploitation of the gift-giving pattern to the extreme of de-manding a Quapaw woman for his wife."

The Wilson sect is still strong among the Osage and the Quapaw, but elsewhere, even among the Delaware and Caddo, it is waning considerably. The Caddo show a disposition to return to the Enoch Hoag "moon," which is considered more "pure" and aboriginal.3° But antagonisms to new elements Wilson sought to introduce date as far back as 1885. About this time Elk Hair was hunting in Comanche territory and learned a ritual he has since kept without change:3'

Elk Hair preferred the Comanche way because it was the pure Indian way .... We brought back to our people the pure Peyote rite and we have used Peyote in the right way ever since.

Elk Hair, according to Petrullo," "has barely managed to keep a following among the Delawares of Dewey," but this region is the stronghold of the Anderson family and if defection of the Anadarko groups to the Hoag moon is any indication, we may expect a reinvigoration of the Elk Hair rite. Indeed, War Eagle wrote from Dewey in 1932 that"

Bacon Rind [whose recent death is mentioned in the letter] was one of the last of the old people who beli[e]ved in [the] Wilson cult; these first followers of peyote are about all gone. [The] small moon now prevales in the Osage. It will be a blessing to the world when all the Quapaws and what few Delawares [are left practicing it] will change [to the standard peyote rite].

1 Mooney, The Ghost Dance, 9o1-9o5.

2 Capt. Hugh L. Scott, in Mooney, The Ghost Dance, 9o4.

3 We have elsewhere expressed the opinion that the Caddo had an historical significance in the spread of peyotism second only to that of the Kiowa-Comanche, and that Wilson represents this Caddoan influence pre-dominantly. Though he had Delaware blood, this numerically small group could scarcely have wielded the in-fluence or exercised the prestige necessary to account for the spread of his "moon:" the Caddo, on the other hand, who early had peyote, did have this prestige. We therefore believe Petrullo in error in claiming Wilson as a Delaware. Speck (Notes on the Life, 54o) writes that "His associations with the Comanche and Caddo, to whom he was related by blood, were close." Petrullo himself, indeed (The Diabolic Root, 44) indicates Caddoan influences on Wilson: "John Wilson, the originator of the Big Moon, was living among the Caddo. He was one of the first Delaware to eat peyote. He belonged to the Black Beaver band . . . held by the Government at the Wichita and Caddo reservations. It was there that Wilson was born and raised." Petrullo also says Wilson made visits to Arizona and New Mexico before returning to make his moon on the Caddo reservation.

4 Note the prominence of hearts in the altar elaborated by Wilson. According to Petrullo (The Diabolic Root, 45) "John Wilson . . . had received some Catholic instruction." These probably derive, therefore, from the Catholic "Sacred Heart." (The heart is present in Huichol religion, but even if not wholly aboriginal [Az-tecan influence?' and Catholic-influenced there too, it is quite independent of the Wilson heart motifs.)

5 Cf. the prominence in Wilson's moon of brushing each person entering with feathers.

6 Cf. the Winnebago leader's similar praying with confessants in peyote meetings.

7 Speck, Notes on the Life, 540-42; cf. also Petrullo, The Diabolic Root, 80.

8 "In response to the question as to whether Wilson ever spoke of the Peyote songs as symbolizing the singing of birds, Anderson asserted that he had heard of this among other Peyote sects but had never heard Wit, son express it." (Speck, op. cit., 542 note.)

9 Some of Wilson's Caddoan teachings were sufficiently unlike those of the Delaware to antagonize them.

A Delaware informant of Petrullo (The Diabolic Root, 66) said, "It [peyote] should be eaten in order to get well, not to have visions." (Benedict's study indicated, one recalls, that in the Woodlands only puberty-visions oc, curred, while in the Plains adults too may obtain them.) Again (p. 68) "Wilson was wrong. Peyote is good, but it is good and powerful medicine, not a religion like the Big House. [For instance] four boiled Peyote placed on top of the head will help in cases of insanity."

10 Cf. the Pawnee (Murie, Pawnee Indian Societies, 642).

11 Petrullo, The Diabolic Root, 172.

12 Petrullo, op. cit., 56-59, 67, 96, note 29.

13 Petrullo (The Diabolic Root, 103). He claims to be Wilson's authorized successor and has revised his moon. Petrullo (op. cit., 4) says John Quapaw is Wilson's real successor.

14 Harrington (Religion and Ceremonies, 156) says Wilson brought the Lenape peyote from the Washita River Caddo as well as the Ghost Dance in t89o-92, which died out with him among the Delaware (idem, 19°- 90.

15 Speck, Notes on the Ethnology, 171.

16 On the mere score of Christian elements we do not agree, however, that Wilson's influence necessarily extended to the Wichita, Winnebago, Kickapoo, and Omaha (Petrullo, The Diabolic Root, 79). See following appendices.

17 Speck, Notes an the Life, 554-

18 Idem, 553.

19 Idem, 544.

20 Idem, 546-

21 For this reason we doubt the soundness of Petrullo's inference that the Omaha, Winnebago, etc., were influenced by Wilson. These groups actually used the Bible in meetings and read from it. This influence, we be. lieve, traces to another teacher, the Oto Jonathan Koshiway.

22 Speck, Notes on the Life, 547-

23 Speck, Notes on the Ethnology, 171.

24 Speck, Notes on the Life, 549.

25 Wilson taught that the number of peyote required to be eaten varies according to the amount of impurity in the "heart" and stomach of the individual, "which impurity resulting from sins committed he likened to 'dirt'" (Speck, Notes on the Life, 545). The more frequently the communicant attended peyote meetings, the less dirt, obviously, there could accumulate. The degree of nausea, Wilson taught, is the punishment meted out for sin (cf. John Rave's teaching)

26 To be sure the pattern of gift-giving is deep-rooted in the Plains, yet it is a curious coincidence at least that Wilson should have taken peyote to the Quapaw, who own the largest lead and zinc mining fields in the world, and the Osage, made notoriously wealthy through oil. Anderson told Speck that the Osage had given Wilson $zoo for building them a moon, and Charles Tyner (Quapaw) told me that he and Victor Griffin (Qua-paw) had received $5oo for an altar in one sum and some hundreds of dollars in money gifts later. The Osage once gave Anderson $zo and his wife $to because his uncle, John Wilson, had built their moon (Speck, op. cit., 554 Wilson even used to charge $1 per person for the sweatbaths he gave before meetings.

27 Petrullo, The Diabolic Root, 81; cf. 45, 95'.

28 Petrullo, op. cit., 45; cf. 104-

29 His followers, in any case, betray their expectancy of financial reward. It was remarked, for example, that the impecunious Seneca gave Anderson only his trainfare when he brought peyote to them. Griffin, more business-like, always arranges beforehand the amount of compensation he is to receive.

30 Cf. the case of the Caddo Alfred Taylor whom the Osage invited to introduce the basic Caddo moon—even the Osage are turning from the Wilson rite.

31 Petrullo, op. cit., 43.

32 Idem, 31-32.

33 War Eagle, letter to Speck from Dewey, Oklahoma April 1, 1932. We believe Petrullo, as shown by this letter, has over-emphasized the decadence of the basic rite at Dewey. The Wilson-Elk Hair antagonism is shown in even trivial ways. The latter use the feathers of swift-flying birds to "hurry up" the medicine cure, the faster the singing of songs, the quicker the cure. The Wilson cultists, who sing slowly, accuse the little moon followers of "putting too much vigor and speed into their healing and praying meetings as is typified by their inclination to decorate their Peyote paraphernalia with Hummingbird feathers, symbolical of the acme of speed." (Speck, Notes on the Life, 551; thanks are due to the University of Pennsylvania Committee of Faculty Research, for Grant No. 93 on which his work was done.)

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|