CHAPTER TEN: THE "DIABOLIC ROOT"

| Books - Hallucinogens and Culture |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER TEN: THE "DIABOLIC ROOT"

The earliest hallucinogenic cactus depicted in ancient American art is a tall, columnar member of the Cereus family, Trichocereus pachanoi, the mescaline-containing San Pedro of the folk healers of coastal Peru (Sharon, 1972). San Pedro has been identified in the funerary effigy pottery and painted textiles of Chãvin, the oldest of a long succession of Andean civilizations, dating to ca. 1000 B.C., and also in the ceremonial art of the later Moche and Nazca cultures, which gives this sacred psychedelic cactus of western South America a cultural pedigree of at least 3000 years.

But the most important, chemically and ethnographically most complex, hallucinogenic member of the cactus family—in terms of its history, the popular, scientific, religious, and legal attention it has drawn, and its cultural utilization from early times to the present—is a small spineless North American native of the Chihuahuan desert, Lophophora williamsii , better known as "peyote."

Despite its relatively restricted desert habitat, extending from the Rio Grande drainage basin in Texas southward into the high central plateau of northern Mexico between the eastern and western Sierra Madre mountains, to the approximate latitude of the Tropic of Cancer, peyote was held in great esteem over much of ancient Mesoamerica, where its earliest artistic representation—in mortuary ceramics found in western Mexico—dates to 100 B.C.-A.D. 200. It is still highly valued by many Indians, and for one indigenous population, the Huichols, it stands as it did in pre-Hispanic times at the very center of a shamanistic system of religion and ritual that has remained uniquely free of major Christian influences.

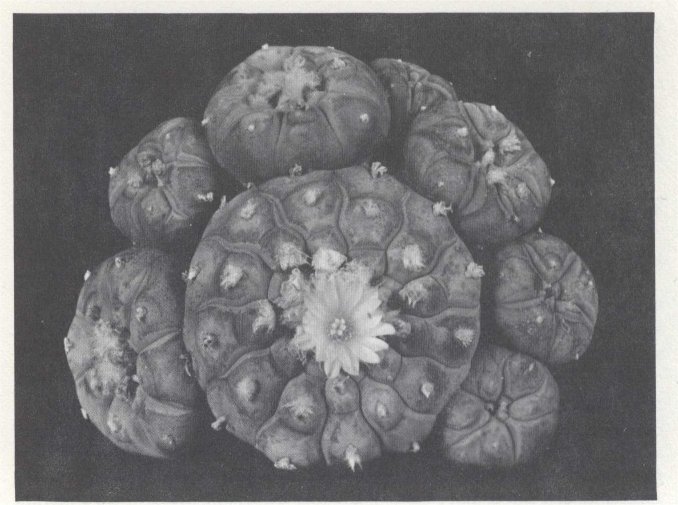

Lophophora williamsii. Peyote in flower; cultivated material from the Rio Grande of Mexico.

Finally, the divine cactus of the Huichols and of earlier peoples has evolved into the sacrament of a new religious phenomenon, the pan-Indian peyote cult which, born out of profound spiritual and sociocultural crisis in the nineteenth century, spread northward from the Texas border as far as the Canadian Plains. Now it is incorporated as the Native American Church, with an estimated 225,000 adherents. Its remarkable history, and that of the long struggle of Indians, anthropologists, and civil libertarians to win legal status for peyote in the face of scientifically absurd and constitutionally questionable state and federal narcotics laws, is documented by La Barre in The Peyote Cult. First published in 1938, this classic anthropological work has been repeatedly brought up to date and republished, most recently in 1969 and again in 1974.* In this chapter and the next, I will attempt from personal experience to convey something of the form and the meaning of "peyotism" in an aboriginal Mexican setting that certainly contributed, if it was not ultimately ancestral to, its North American manifestation.

A "Factory of Alkaloids"

Peyote is popularly identified with its best-known alkaloid, mescaline, but in fact mescaline is only one of more than thirty different alkaloids that have so far been isolated, together with their amine derivatives, from this remarkable plant, which Schultes (1972a) aptly calls "a veritable factory of alkaloids." Most of these constituents belong to the phenylethylamines and biogenetically related simple isoquinolines; and almost all are in one way or another biodynamically active, with mescaline as the principal vision-inducing agent (p. 15).* But peyote is a very complex hallucinogenic plant, whose effects include not only brilliantly colored images as well as shimmering auras that appear to surround objects in the natural world, but also auditory, gustatory, olfactory, and tactile sensations, together with feelings of weightlessness, macroscopia, and alteration of space and time perception. Because of the physiological interaction of the different alkaloids in the whole plant, Schultes cautions against too close an equation of the effects of synthetic mescaline, such as those described so eloquently by Aldous Huxley, with the psychic experiences of Indian peyotists.

Although the Church did not hesitate to employ the harshest measures to banish peyote from native use as "the diabolic root," at one point going so far as to equate its consumption with cannibalism (!), the cult of the sacred cactus survived Colonial repression; the supernatural and therapeutic powers anciently attributed to it remained intact. One reason certainly was the physical isolation of some of the groups that most esteemed peyote. The Huichols and their close cousins the Coras, for example, continued to enjoy relative freedom from Spanish overlordship even after their rugged territory in the western Sierra Madre was nominally brought under Colonial military and ecclesiastical sway about 1722. Missions were established but the Indians successfully resisted conversion. There was some acculturation, but ideologically and physically the Huichols continued to be relatively autonomous, a condition that became even more pronounced after Mexican independence. It is this isolation from the sociological and religious mainstream of post-Conquest Mexico that largely explains why the 10,000 Huichols preserved so much more of their pre-European religious heritage than did other Mesoamerican Indians.

In modern Mexico peyote has long been available in many herbal markets as a highly esteemed medicinal plant. Nor do the Huichols (who more than any other indigenous population consider peyote sacred—indeed, divine—and who take it mainly in ceremonial contexts) have any sanctions, legal or ethical, against its extraritual use. It is employed by them therapeutically against a variety of physical ills, it is taken for relief from fatigue, and it is often consumed just for its pleasurable psychic sensations. But it is never regarded simply as a "drug," never deemed on a par with other chemicals with which the Huichols have become increasingly familiar through the Government's medical services to even the most remote Indians. A newspaper reporter who made the mistake of calling peyote a "drug" while interviewing a Huichol shaman in my presence was indignantly told, "Aspirina is a drug, peyote is sacred," and warned not to confuse such important matters.

"Mescaline": A Misnomer

I should mention here that not only "mescaline" but also "peyote" are actually misnomers. Lophophora williamsii, sometimes called "mescal button" (hence "mescaline") has nothing whatever to do with the species of agave from which the potent liquors known as mescal and tequila are distilled. "Peyote" itself derives from the Aztec peyótl, a term that was applied not just to Lophopora williamsii but also to several other unrelated plants with medicinal properties. The Huichols call the sacred cactus hikuri, and since they share this term with several other peoples belonging to the Uto-Aztecan or Nahua language family, hikuri is probably the correct aboriginal name.

That peyote, like coca (Erythroxylon coca) in the Andes, is an effective stimulant against fatigue has been known for some time. For this we have, among others, the testimony of Carl Lumholtz (1902), the Norwegian pioneer ethnographer of the Huichols and other Mexican Indians, who traveled widely in the Sierra Madre in the 1890's. On one occasion, totally exhausted at the bottom of a deep canyon after a long trek and unable to walk another step (to make matters worse he had just recovered from a bout with malaria), he was given a single hikuri by his Huichol friends:

The effect was almost instantaneous, and! ascended the hill quite easily, resting now and then to draw a full breath of air. (pp. 178-179)

More interesting still are recent laboratory tests confirming that when the Indians call peyote "medicine" it was not in terms just of supernatural power ("medicine power" in Plains Indian terminology) but rather of actual medication. Researchers at the University of Arizona isolated a crystalline substance from an ethanol extract of peyote which, they found, exhibited antibiotic activity against a wide spectrum of bacteria and a species of the imperfect fungi, including strains of penicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (McLeary, et al., 1960:247-249).

The Huichols, to whom peyote is synonymous with and qualitatively equivalent to the divine deer or supernatural Master of the Deer Species, take the hallucinogenic plant mainly in two forms. One is the fresh cactus itself, whole or cut into pieces, in which form it is equivalent to the flesh of the deer. The other is the cactus macerated or ground on a metate and mixed with water. The latter combination symbolizes, among other meanings, the symbiosis or interdependence of the dry season and the wet, hunting and agriculture, and male and female (cactus and deer being male and water female).

The Sacred Quest for Peyote

Peyote is not native to the Sierra Madre, so that the Indians have to travel long distances to obtain the necessary supplies—for the ceremonies, personal use, and trade to Indian neighbors. While this pilgrimage is by far the most sacred enterprise in the annual ceremonial cycle and also serves as a rite of initiation, not every Huichol adult has been a participant, nor can it even be said that everyone has tasted peyote. The pilgrimage is not required, but like that of the devout Moslem to Mecca, it is a sacred task, fraught with enormous potential benefit for one's own life and the welfare of one's kin, a task to which many Indians aspire at least once, to which would-be shamans must commit themselves a minimum of five times, and which some of the oldest and most traditional have repeated as many as ten, twenty, or, in rare instances, even thirty times over their lifetime.

For at the end of that long and arduous trail, 300 miles northeast of Huichol territory, in the high desert of San Luis Potosi, lies Wirikuta, the mythic place of origin. Here dwell the supernaturals known as the Kakauyarixi, the Ancient Ones, divine ancestors, in their sacred places. Here the hikuri, the magic cactus, manifests itself as Elder Brother Deer, the mediator whose divine flesh enables not just the elect, the shaman, but also the ordinary Huichol to transcend the limitations of the human condition—"to find his life," as the Indians say.

Mythic Origins of Peyote

I remember one elderly mara'akizme (the Huichol term meaning both curing and singing shaman and sacrificing priest) of great renown, of whom it was said that he had made this difficult journey no less than 32 times—on foot! Walking in both directions was the traditional way, but nowadays most Huichol peyoteros make use of whatever transportation is available—autos, trucks, buses, horse-drawn wagons, even the train. This is acceptable so long as all the sacred places along the way are properly acknowledged with offerings and prayer, and all other ritual requirements are fulfilled. The pattern was established long ago, in mythic times, when the Great Shaman,

Fire, addressed as Tatewari, Our Grandfather, led the ancestral gods on the first peyote quest. It is told that the fire god came upon them as they sat in a circle in the Huichol temple, each complaining of a different ailment. Asked to divine the cause of their ills, the Great Shaman, Fire, said they were suffering because they had not gone to hunt the divine Deer (Peyote) in Wiriktita, as their own ancestors had done, and so had been deprived of the healing powers of its miraculous flesh. It was decided to take up bow and arrow and to follow TatewarI to "find their lives" in the distant land of the Deer-Peyote.

These gods were male, but true to Huichol belief that only unification and proper balance of male and female guarantees life, along the way, at the sacred water holes in the desert the Huichols call Tateimatinieri, Place of Our Mothers, they were joined by the female component of the Huichol pantheon, the Mother Goddesses of terrestrial water and rain, and of the fertility and fecundity of the earth and all the phenomena of nature, including humanity. In their animal aspect these mother goddesses are snakes, a symbolic identification the present-day Huichols share with pre-Hispanic peoples.

Every Huichol is completely familiar with this peyote tradition and the sacred itinerary. Each year, when the first ears of maize and the first young squashes have ripened in the fields, a lengthy ceremony is held for the youngest children, who are equated with the first fruits of agriculture, and for whom the shaman-elder of the kin group recites the story in repetitive song to the accompaniment of his magic drum.

I participated in two peyote pilgrimages, in 1966 and again in 1968. What follows is essentially based on the second of these, when we transported sixteen Huichols, including four women and three children, the youngest only seven days old at the outset, from Nayarit in western Mexico to Wiriktita in two motor vehicles.* Both these pilgrimages were led by the late Raman Medina Silva, a charismatic, gifted artist and shaman who had lived for some years on the fringes of traditional Huichol subsistence-farming society but who was nonetheless firmly committed to the validity of Huichol religion and tradition. The 1968 pilgrimage was his fifth, culminating his self-training as a mara'alaime . He was to lead two more, one entirely on foot (in fulfillment of a commitment to the divine ancestors for curing his wife Lupe of rheumatoid arthritis), before his tragic death in June 1971 in a shooting incident during a fiesta to celebrate the clearing of Sierra forest land for a new maize plot. Such fiestas customarily involve much drinking and it was this that led to his death. He was then about 45 years old.

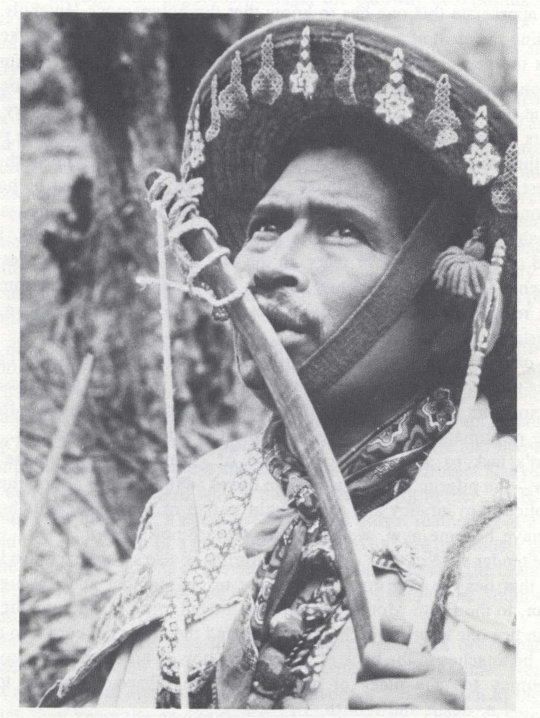

Ramon. The leader of the peyote quest described in these pages, using his hunting bow as ritual musical instrument. This is the same weapon with which the sacred cactus, identified with the deer deity, is "hunted" and sacrificially slain.

As the German ethnographer Konrad Theodor Preuss (1908) observed earlier in this century, Huichol shamanism and ritual, while sharing many basic elements, tend toward the idiosyncratic in actual performance, and no two shamans, even from the same community, are likely to agree entirely on a single rendition of a particular tradition. Nonetheless, the basic structure remains. So it was with Ramón's version of the peyote quest: here and there it differed from others that have been described to me, but in its essentials it conforms remarkably well to those recounted, on the basis of informants' statements, by Lumholtz and more recent students of Huichol culture.

"We Are Newly Born"

Absolutely essential to the physical and metaphysical success of the sacred peyote enterprise is a rite of sexual purification, intended to return the pilgrims to a state of prenatal innocence. It requires all those present, men and women, to identify by name and in public each and every sexual partner since puberty. This applies even to those who will not actually make the journey but remain behind to keep the divine hearth fire—one of the manifestations of the fire deity—burning for the duration of the pilgrimage.

To appreciate this one has to know that the polygamous Huichols, while espousing the ideal of marital fidelity, are not especially noted for adhering to it, that the participants are usually drawn from the same small community, commonly from households more or less closely related by blood or marriage, and that the attentive audience more likely than not includes the very sexual partners whose names are publicly proclaimed. Yet it is an absolute requirement that no one present, be it husband, wife, or lover, must show the slightest sign of anger or jealousy. Indeed, such feelings must be banished from one's innermost being—"one's heart," as the Indians say—and the confessions must be received with good humor, even high spirits. Hence, instead of recriminations or tears, in the two sexual purification rites which we attended there were laughter, shouts of encouragement, and sometimes joking reminders from husbands, wives, and other relatives of love affairs inadvertently or deliberately omitted.

As officiating shaman and manifestation of the old Fire God Tatewari (who is also present in the ceremonial fire around which the group assembles as personators of the original, divine pilgrims of mythic times—for each peyote pilgrimage reenacts the first quest for the divine cactus), it was Ramon's task to accept the confession of sexuality and "unmake"—i.e. reverse—the pilgrim's passage through life to adulthood and return him or her symbolically to infancy and a state akin to that of spirit. The Huichols say: "We have become new, we are clean, we are newly born."

The tender state of the "newborn" pilgrims is also symbolized in a knotted string that ties the pilgrims symbolically to one another and, through their shaman, to the Earth Mother herself. As though tying off the umbilicus, the shaman ties one knot for each companion and then rolls the cord into a spiral which he attaches to the back of his hunting bow. This spiral is metaphor for the journey to "the place of origin" and the subsequent return to "this world"—i.e. death and rebirth.

The symbolic navel cord whose knots will be untied upon their return from Wiriktita must not be confused either with the knotted calendar cord mentioned by Lumholtz (but omitted in our two pilgrimages), or with yet another knotted string that plays a crucial role in the obliteration of adult sexuality. This cord is one into which the shaman has "tied" everyone's sexual experience and whose sacrifice by fire completes the purification rite.

The Dangerous Passage

Having symbolically shed their adulthood and human identity the pilgrims can now truly assume the identity of spirits, for just as their leader is Tatewari, the Fire God and First Shaman, so they become the ancestral deities who followed him on the primordial hunt for the Deer-Peyote. In fact, it is only when one has become spirit that one is able to "cross over"—that is, pass safely through the dangerous passage, the gateway of Clashing Clouds that divides the ordinary from the nonordinary world. This is one of several Huichol versions of a near-universal theme in funerary, heroic, and shamanistic mythology.

That this extraordinary symbolic passage is today located only a few yards from a heavily traveled highway on the outskirts of the city of Zacatecas seemed to matter not at all to the Huichols, who in any case acted throughout the sacred journey as though the twentieth century and all its technological wonders had never happened, even when they themselves were traveling by motor vehicle rather than on foot! Indeed, to us nothing illustrated more dramatically the time-out-of-life quality of the whole peyote experience than this ritual of passing through a perilous gateway that existed only in the emotions of the participants, but that was to them no less real for its physical invisibility.

We arrived at the outskirts of Zacatecas in midmorning. Assembling in their proper order as decreed in ancient times by Tatewarl, the pilgrims proceeded in single file to a grove of low-growing cactus and thorn bushes a few hundred feet from the highway. They listened with rapt attention as Ramon related the relevant passages of the peyote tradition and invoked for the coming ordeal the protection and assistance of Elder Brother Kauyumarie, a deer deity and culture hero who is the shaman's spirit helper. At Ramón's direction, each then took a small green and red parrot feather from a bunch attached to the straw hat of a mateweime (one who has not previously gone on a peyote pilgrimage, i.e. an unitiated neophyte), and tied it to the branches of a thorn bush in a propitiatory rite that has analogies among the Southwestern Pueblos

Some distance up the road the pilgrims were led to an open space that commanded a fine view of the valley from which we had come. Here they formed a semicircle; men to Ramón's left, women and children to the right. Although they knew the peyote traditions by heart they listened carefully as he told them how, with the assistance of Kauyumarie's antlers, they would soon pass through the dangerous Gateway of Clashing Clouds. But from now until they arrived at the Place Where Our Mothers Dwell, the matewámete (pl.) among them would have to "walk in darkness," for they were "new and very delicate." Beginning with the women at the tail end of the line, Ramón proceeded to blindfold the novices. Even the children had their eyes covered, down to the baby.

Everyone took the blindfolding very seriously, some actually wept, but there were also the quick shifts between solemnity and humor that are so characteristic of Huichol ceremonial. Spirited and comical dialogues ensued between Ramon and veterans of previous pilgrimages: was the companion well fed, had he quenched his thirst? Oh yes, one's stomach was full to bursting with all manner of good things to eat and drink. Did one's feet hurt after so much walking? Oh no, one walked well, in comfort. (In reality none had had more than the most meager nourishment, only five dry tortillas per day and no water at all being permitted on the road to Wiriktita. As for walking, we were of course traveling by car, although the proper acknowledgement of various sacred places along the way repeatedly required single-file marches in and out of the desert).

Following the ritual blindfolding, Ramon led the pilgrims a few hundred years northeastward. Here, a place entirely unremarkable to the untutored eye, was the mystical divide, the threshold to the divine peyote country. The pilgrims remained rooted where they stood, intently watching Ramon's every move. Some lit candles they had stored in their carrying bags and baskets. Lips moved in silent or barely audible supplication. Ramón bent down and laid his bow and arrows crosswise over his oblong takwátsi, the plaited shaman's basket—bow and deerskin quiver pointing east in the direction of Wiriküta.

There are two stages to the crossing of the critical threshold. The first is called Gateway to the Clouds; the second, Where the Clouds Open. They are only a few steps apart, but the emotional impact on the participants as they passed from one to the other was unmistakable. Once safely "on the other side," they knew they would travel through a series of ancestral stopping places to the sacred maternal water holes, where one asks for fertility and fecundity and from where the novices, their blindfolds removed, are allowed to have their first glimpse of the distant mountains of Wiriktita. Of course, one would search in vain on any official map for places that bear such names as Where the Clouds Open, The Vagina, Where Our Mothers Dwell, or even Wirikiita itself, either in Huichol or Spanish. Like other sacred spots on the peyote itinerary, these are landmarks only in the geography of the mind.

Visually, the passage through the Gateway of Clashing Clouds was undramatic. Ramón stepped forward, lifted the bow and, placing one end against the mouth while rhythmically beating the taut string with a composite wooden-tipped hunting arrow, walked straight ahead. He stopped once, gestured (to Kauyumarie, we were later told, to thank him for holding the cloud gates back with his powerful antlers), and set out again at a more rapid pace, all the while beating his bow. The others followed close behind in single file. Some of the blindfolded neophytes held fearfully on to those in front, others made it by themselves.

"Where Our Mothers Dwell"

It was in the afternoon of the following day that we reached the sacred water holes of Our Mothers, the novices having remained blindfolded all the while. The physical setting again was hardly inspiring: an impoverished mestizo pueblo and beyond it a small cluster of obviously polluted springs surrounded by marsh—all that remained of a former lake long since gone dry. Cattle and a pig or two browsing amid the sacred water holes hardly helped inspire confidence in the physical—as opposed to spiritual—purity of the water the Huichols considered the very wellspring of fertility and fecundity. On the peyote quest, however, it is not what we would consider the real world that matters but only the reality of the mind's eye. "It is beautiful here," say the Huichols, "because this is where Our Mothers dwell, this is the water of life."

For some time, while the veteran peyoteros busied themselves in ritual activities, the blindfolded matewitmete were made to sit quietly on the earth in a row, knees drawn up and arms held tightly against the body—the fetal position. Then at last the moment came when they could emerge into the light—i.e. be born—by the removal of their blindfolds. As Ramón did this in a separate ritual for each that included the same sort of jocular dialogue as had marked the dangerous passage, he also poured an ice-cold bowl of water taken from one of the springs over their heads, instructing them to rub the fecund fluid deeply into scalp and face. A second gourdful was handed them to drink, along with presoaked animal crackers and bits of tortilla, "for they are new, they can only eat tender food."

Offerings were left in the springs and numerous bottles and other containers filled with the precious water. The manner in which this filling was accomplished unmistakably celebrated the union of male and female, for Ramón and other peyoteros would dip a hunting arrow into a water hole and on its hardwood tip withdraw a few drops; the arrow would then be inserted into a waiting bottle and the drops shaken off in a motion simulating sexual intercourse. With this all ritual requirements preparatory to the actual hunt—bow and arrow in hand—for Elder Brother Deer-Peyote had been fulfilled. The water would first be taken to Wiriktita and then home, for use in the peyote rites and other ceremonies, and to be sprinkled with sprays of flowers over the women and even female livestock by the returning pilgrims, a symbolic act of fertilization that reminds one of the pre-Hispanic tradition in which the Toltec ruler Mixcóatl fathers the priest-king and culture hero Quetzalcóatl by impregnating his wife with the spray of flowers (an alternate version speaks of a jewel of jade). The contents of the springs of Our Mothers are thus seen to embody both male and female aspects.

*The anthropological literature is rich in North American peyote studies, outstanding among them the writings of Omer C. Stewart on Ute and Paiute peyotism, David F. Aberle's The Peyote Religion among the Navaho (1966), and J. S. Slotkin's The Peyote Religion (1956). The latter is especially interesting because Slotkin, an anthropologist, himself joined the Native American Church of North America and became one of its elected officials. His book was intended, he wrote (1956:v), as a "documented exposition of Peyotism for Whites, from the Peyotist point of view." For public support by anthropologists for religious freedom for Indian peyotists see, for example, La Barre et al. , "Statement on Peyote," in Science (1951:582-583).

*The giant saguaro cactus (Carneglea glgantea, also known as Cereus glganteus) of the Sonoran desert in Arizona and northern Mexico has been found to contain three alkaloids closely related to the tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids in Lophophora willlamsll (peyote). These are camegine, salsoidine, and gigantine, the latter said to cause hallucinogenic reactions (Bruhn, 1971:320-329). As noted elsewhere, dopamine has also been isolated in the stems of the saguaro. Saguaro fruit was a favorite food of the Indians of the region, who also used it to make a potent alcoholic beverage consumed at an annual festival called, in Pima, Navalta, from navait. intoxicating drink or wine (the Huichols call their fermented maize drink by the related term nawá). Whether the Pima, Papago and other peoples of the area, or their prehistoric ancestors, ever made use of the alkaloid-containing saguaro stem, for curing or other ritual purposes, is not known, but Mexican Indians to this day value close relatives of the saguaro for their curative powers.

*For other first-hand data on the peyote pilgrimage see Barbara G. Myerhoff s The Peyote Hunt (1974), an excellent anthropological analysis of the whole deer-corn-peyote symbol complex, and Fernando Benitez, In the Magic Land of Peyote (1975), a sympathetic and insightful chronicle of the pilgrimage and its meaning by a well-known Mexican historian-journalist. Dr. Myerhoff s book deals with the 1966 peyote hunt, in which we were both privileged to be "participant observers."

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|