CHAPTER NINE: R. GORDON WASSON AND THE IDENTIFICATION OF THE DIVINE SOMA

| Books - Hallucinogens and Culture |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER NINE: R. GORDON WASSON AND THE IDENTIFICATION OF THE DIVINE SOMA

In the second millennium before our Christian era, a people who called themselves "Aryans" swept down from the Northwest into what is now Afghanistan and the Valley of the Indus. They were a warrior people, fighting with horse-drawn chariots; a grain-growing people; a people for whom animal breeding, especially cattle, was of primary importance; finally, a people whose language was Indo-European, the Vedic tongue, the parent of classical Sanskrit, a collateral ancestor of our European languages. They were also heirs to a tribal religion, with an hereditary priesthood, elaborate and sometimes bizarre rituals and sacrifices, a pantheon with a full complement of gods and other supernatural spirits, and a mythology rich with the doings of these deities. Indra, mighty with his thunderbolt, was their chief god, and Agni, the god of fire, also evoked conspicuous homage. There were other gods too numerous to mention here. Unique among these other gods was Soma. Soma was at the same time a god, a plant, and the juice of that plant.

So Wasson begins his remarkable work, Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality, first published in 1968 and republished in 1971 in a popular edition. The Soma sacrifice, in the words of the Vedic scholar Dr. Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty in her review of the post-Vedic history,

. was the focal point of Vedic religion. Indeed, if one accepts the point of view that the whole of Indic mystic practice from the Upanisads through the more mechanical methods of yoga is merely an attempt to replace the vision granted by the Soma plant, then the nature of that vision—and of that plant—underlies the whole of Indian religion, and everything of a mystical nature within that religion is pertinent to the identity of the plant. (quoted in Wasson, 1968:95)

The Elusive Soma Deity

But that was just the problem—however many species different Vedic scholars have identified with Soma in the nearly two centuries since Sanskrit was first translated into European languages, its true identity proved elusive. Soma and its sacrifice are celebrated in many hymns, but the Rig Veda was sung by the ancient poet-priests for their contemporaries, who did not need to be told what Soma was precisely, and they obscured the mysterious plant god's natural morphology with all sorts of poetic imagery and inspired metaphors that hardly qualify, nor were intended, as botanical descriptions (e.g. "mainstay of the sky," with his foot at the earth's navel and his crown in the heavens; "divine udder," "he has clothed himself with the fire-bursts in the Sun," and the like).

Among the plants which Vedic scholars have put forward as Soma have been Sarcostemma brevistigma and related species; Ephedra vulgaris; Ipomoea muricata; different species of Euphorbia; Tinospora cordifolia (a climbing shrub an extract of which is used as an aphrodisiac and a cure for gonorrhea in Indian folk medicine); Peganum harmala, Cannabis indica (in the form of bhang), and even rhubarb. Others have suggested that Soma might have been a fermented drink or a distilled liquor. But there is nothing in the Rig Veda to suggest a process of fermentation, and distilled alcohol was as unknown in ancient India as it was in the New World before the coming of the Spaniards, not to mention that liquor would have been anathema to the devout Hindu. As a matter of fact, the Rig Veda informs us exactly how the marvellous drink was prepared: the dried Soma plants were moistened with water to make them swell up again and pounded with pestles. After being filtered through a fine woolen cloth, the tawny yellow inebriating juice was imbibed by the Vedic priests in their sacrificial rites. The effects, as these emerge from the poetic imagery of the hymns, were clearly what we would now call hallucinogenic or psychedelic.

Of the numerous species that have been proposed over the years the most persistent had been the aforementioned Sarcostemma, a leafless sprawling herb with a milky juice that is employed as an emetic in Indian folk medicine. It is true that the Rig Veda describes Soma as having no leaves, but unlike the red-flowered Sarcostemma, the mysterious Soma plant also lacked roots and blossoms. Nor is there evidence that Sarcostemma has psychoactive properties, particularly of the kind implied in such Vedic hymns as one that speaks of the priestly imbiber of the divine Soma having the power of flight beyond the limits of heaven and earth and feeling strong enough to pick up the earth itself and move it about wherever he desired.

Indeed, not one of the plants identified with Soma before Wasson's flyagaric theory burst upon the scene of Vedic scholarship

. . . has carried any conviction, and all are implausible philologically, botanically, and pharmacodynamically. It is no wonder that most ranking twentieth-century scholars have come to regard the problem of soma as insoluble. (La Barre, 1970c:370)

Multidisciplinary Quest

Wasson initiated his quest for Soma in 1963, and he did so from entirely different points of view than had the Vedists. Above all, he recognized his own limitations and drew on a wide variety of disciplines and international experts in their respective fields to assist him. Basically his problem was this: Soma was clearly a hallucinogenic plant with certain well-defined subjective effects but lacking a botanical identity. As early as the first millennium B.C. the real Soma plant disappeared from Vedic ritual and the name came to be applied to various substitutes, of which none had the same psychic effects as the original Soma and all of which were known at least to the priestly caste to be substitutes. This assumption cannot be proven, admits Wasson, but must have been a fact from the very beginning:

The contrast between the ecstasy of Soma inebriation as sung in the hymns and the effects, often vile, of any of the many substitutes was always too glaring to be ignored. (1968:7)

But it is the substitutes with which the commentaries on the Vedas, the Brahmanas, written after 800 B.C., concern themselves, and it is they, not the original Vedas, that form the basis for all the plants that have been identified with Soma by western as well as Indian scholars. Wasson's methodological astuteness, writes La Barre (1970c),

has been to use the Rig Veda evidence alone, eschewing the tempting but wholly irrelevant prolixity of the Brahmanas. When taken all together and respected literally for what they say, the Vedic apostrophes to Soma turn out to be quite exact and mutually consistent botanical descriptions of the mushroom Amanita muscaria. . . the fly agaric. (p. 370)

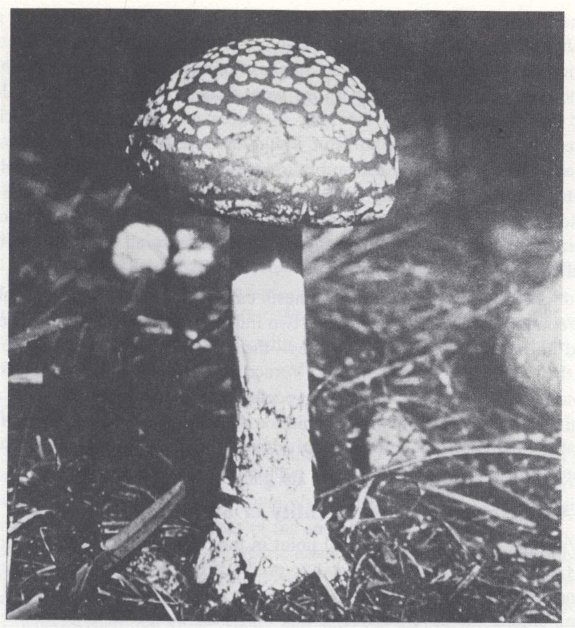

Amanita muscaria. The divine Soma of the ancient Indo-Europeans and magic hallucinogenic mushroom of Siberian shamanism. Courtesy R. Gordon Wasson.

Wasson proposed that the "Aryans" arrived in the Indus Valley from their homeland to the northwest with a well-integrated ancestral cult of the sacred fly-agaric, and that what remained of archaic Siberian mushroom ritual in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries actually represents a kind of fossil of the ancient ecstatic-shamanistic stratum in which the Vedic rites of the early second millennium B.C. had their ultimate roots. If so, then the Vedic priests would from the start have had to wrestle with the problem of substitutes for the divine plant, for the fly-agaric is not always and everywhere available and like most mushroom species cannot be cultivated. It can, of course, be dried and preserved. And here the Rig Veda's description of Soma's preparation—a dried, leafless, rootless, blossomless plant to which water was added to make it swell up again—certainly suggests dried mushrooms. Similarly, the effects of the divine inebriant—including sensations of enormous strength, already mentioned in the Koryak myth, and of flight to the ends of the universe—fit precisely those of Amanita muscaria. Likewise, once one accepts the idea that Soma was the fly-agaric, many previously obscure Vedic passages that allude with poetic metaphors to Soma's appearance fit remarkably well those of the fly-agaric in its different stages.

But why would the priests have abandoned so miraculous and divine a plant in favor of substitutes that lacked the marvellous properties of the original Soma? Even this falls into place as a function of environmental adaptation once one accepts Wasson's thesis. The fly-agaric, as he points out, is a mycorrhizal mushroom which in Eurasia, including the ancient homeland of the Indo-European Vedic-speakers, grows only in an underground relationship with the pines, the firs, and above all, the birches. Where there are no such trees there is no fly-agaric. Stands of conifers were not inaccessible to the northern settlers of India but they were distant; the mushrooms could be dried and transported but the long distances and other factors, such as unpredictable seasonal availability, would have made substitution necessary and acceptable—certainly preferable to total abandonment of the traditional rituals themselves. Eventually, and perhaps even deliberately, the real Soma would have come to be forsaken altogether and its identity, though not its sacred meaning and its psychic effects, forgotten by all but the innermost privileged circle of priests.

I might add here that Wasson's thesis can be supported with an analogy from contemporary Mexico. At least two Indian populations that traditionally relied on peyote for their curing rites—the Tepehuanos of western Mexico and the (unrelated) Tepecanos of Veracruz—are known to have recently adopted a post-Hispanic import, a species of Cannabis (marihuana), as a substitute, because peyote has become too difficult and costly to obtain from its natural habitat in the north-central Mexican desert, several hundred miles distant from both these indigenous populations.

Fly-Agaric Urine and the Identity of Soma

With this we come to a crucial point in the development of the argument for Amanita muscaria, one that has predictably caused no end of debate among scholars. The psychoactive properties of the fly-agaric, we recall, are unique among the psychedelics in that they pass unaltered through the kidneys, which explains why in Siberia it was customarily taken in two forms:

First Form: Taken directly, and by "directly" I mean by eating the raw mushroom, or by drinking its juice squeezed out and taken neat, or mixed with water, or with water and milk or curds, and perhaps barley in some form, and honey; also mixed with herbs such as Epilobium spp.

Second Form: Taken in the urine of the person who has ingested the fly-agaric in the First Form. (Wasson, 1968:25)

Now, Wasson points out, the Rig Veda refers unmistakably to two forms of Soma. This in itself is not a new discovery, but as he notes, the interpreters of the sacred hymns, knowing nothing of the ethnobotany and chemistry of Amanita muscaria, always assumed that the first form was Soma juice alone and the second Soma mixed with curds or milk. Wasson demonstrates that the two forms parallel rather precisely the two forms of the fly-agaric in Siberian shamanism. For the god Indra and the priests are actually spoken of by the poets as drinking Soma and pissing it. One famous verse, cited by the noted Sanskrit scholar Daniel H. H. Ingalls (1971) of Harvard in a review of Wasson's Soma, addresses the god Indra thusly:

Like a thirsty stag, come here to drink. Drink Soma, as much as you want.

Pissing it out day by day, 0 generous one,

You have assumed your most mighty force.

This cannot but remind us of the close association between fly-agaric and reindeer in Siberia. The same can also be said of passages that refer to the Rudras, zoomorphic storm deities that protected cattle, drinking and pissing Soma in the form of brilliantly shining and colored horses.

Wasson does not assert that the Vedic priests actually drank Soma-urine, but he cites passages from early sacred texts as well as later ones that at least allude to such a Siberian-like practice—e.g. Zarathustra's excoriation in the Gatha of the Avesta, Yasna 48.10: "When will you (0 Mazdah) do away with the urine of this drunkenness with which the priests evilly delude the people?"

The Controversy Lives On

As might be expected, the identification of Soma as a mushroom was not greeted with equal enthusiasm among all Vedic scholars, nor has everyone who accepts his basic thrust—that Soma was the fly-agaric—agreed with each and every one of his interpretations of the ancient texts. Professor Ingalls, for example, fully agrees with the fly-agaric identification but not with his theory of urinated Soma. The most vehement criticism came from an eminent British scholar, John Brough, Professor of Sanskrit at the University of Cambridge (1971), who insisted that Soma cannot and must not be identified on any but internal evidence from the Rig Veda itself—a task that has proved insoluble to Vedic scholars—and that any parallel data from outside the Indo-Iranian sphere, such as those from Siberia, are extraneous and irrelevant. Wasson's detailed rejoinder (1972c) published in November by Harvard's Botanical Museum, makes a point that is as applicable to all the sciences—hard, social, natural, or humane—as it is to the discipline to which it is specifically addressed:

Let the Vedists leave off feeding exclusively on the Rig Veda and each other. Let them be on easy terms with the outside world, with botanists, chemists, pharmacologists, physiologists: with anthropologists, prehistorians, and students of religion among early cultures, living and moribund and dead. Brough's paper on every page shouts his need (unfelt by him) for those interdisciplinary contacts to which on principle he closes his eyes and ears. If the older generation of Vedists includes many for whom this expanded opportunity is disturbing, younger scholars will certainly seize on it with enthusiasm. (p. 41)

And not just younger scholars either. The greatness of a discovery, writes Professor Ingalls in the aforementioned comment on Wasson's book,

• . lies in the further discoveries that it may render possible. To my mind the identification of the Soma with an hallucinogenic mushroom is more than a solution of an ancient puzzle. I can imagine numerous roads of inquiry on which, with this new knowledge in hand, one may set out. In a few paragraphs I shall indicate only one such road, a road on which I have traveled a short distance. (1971:190)

Reading Wasson, he writes, inspired him to study Rig Veda Book 9, which deals primarily with Soma. As a result he began to perceive a qualitative difference between the Soma hymns and certain other hymns of the Rig Veda:

The two poles seem to me to be the Soma hymns and the Agni hymns. The two gods represent the two great roads between this world and the other world. . . . They run straight through; they are the great channels of communication between the human and the divine: the sacred fire and the sacred drink.* Greatly to simplify matters, I would put the difference between the Agni hymns and the Soma hymns this way. The typical Agni hymn juxtaposes a given ritual with a mythical prototype, with the "prathamani dharmani." The ritual is intended to reactivate the prototype and to give to the participants the strength of their semi-divine ancestors. The Soma hymns, on the other hand, employ their imagery quite differently. The ascent of Soma to the river of heaven is not an act in the mythical past. It is happening right now, as the Soma juice cascades through the trough. (p. 191)

The Agni hymns are reflective, mythological, seeking for harmony between this world and the sacred but always aware of the distinction, while the Soma hymns concentrate on the immediate experience:

I am speaking of two sorts of religious expression and religious feeling, one built about the hearth fire, with a daily ritual: calm, reflective, almost rational; the other built around the Soma experience which was never regularized into the calendar, which was always an extraordinary event, exciting, immediate, transcending the logic of space and time. (p. 191)

Much of this parallels in the most exciting and specific way the peyote ceremony of the Huichols of Mexico. For there again we find the same juxtaposition: on the one hand, the fire god, at once sacred hearth and mediator between the everyday world and the world beyond, the great fire shaman who leads the peyoteros into the mythic past, and on the other the divine hallucinogen, Deer-Peyote, and the immediate, ecstatic experience that transcends the boundaries between the here and now and the there and then. But this takes us a bit ahead of ourselves (see Chapters Ten and Eleven).

A New Road of Inquiry

Wasson (1972b) himself also embarked on a "new road of inquiry" that led him to make the intriguing suggestion that the very concept of the Tree of Life and the Marvelous Herb that grows at its base in the folklore of many peoples might have had its genesis in the mycorrhizal relationship between the fly-agaric and certain trees, above all the birch and the pine. Throughout Siberia, he points out, the birch is revered as the shaman's sacred tree, which he ascends in his trance to reach the Upperworld:

Uno Holmberg, in the Mythology of all Races, has summarized for us the folk beliefs that surround the birch. The spirit of the birch is a middle-aged woman who sometimes appears from the roots or trunk of the tree in response to the prayer of her devotee. She emerges to the waist, eyes grave, locks flowing, bosom bare, breasts swelling. She offers milk to the suppliant. He drinks, and his strength forthwith grows a hundredfold. . . . In another version the tree yields "heavenly yellow liquor." What is this but the "tawny yellow pavamana" of the Rig-Veda? Repeatedly we hear of the Food of Life, the Water of Life, the Lake of Milk that is hidden, ready to be tapped near the roots of the Tree of Life. There where the Tree grows near the Navel of the Earth, the Axis Mundi, the Cosmic Tree, the Pillar of the World. What is this but the Mainstay-of-the-Sky that we find in the Rig-Veda? The imagery is rich in synonyms and doublets. The Pool of "heavenly liquor" is often guarded by the chthonic spirit, a Serpent, and surmounting the tree we hear of a spectacular bird, capable of soaring to the heights, where the gods meet in conclave. (pp. 211-213)

Wasson proposes that this well-known theme had its origin in the Eurasiatic forest belt and not, as has sometimes been suggested, in Mesopotamia and the ancient Near East, where it is found in the Sumerian Gilgamesh epic and, in somewhat different but obviously related form, the Book of Genesis. If his reconstruction holds good, Wasson concludes,

. . . the Soma of the Rig-Veda becomes incorporated into the religious history and prehistory of Eurasia, its parentage well established, its siblings numerous. Its role in human culture may go back far, to the time when our ancestors first lived with the birch and the fly-agaric, back perhaps through the Mesolithic and into the Paleolithic. (p. 213)

If it is indeed that ancient, it would also help explain why the same motif is found in strikingly similar form in Maya art as well as in shamanic tradition and ritual of other indigenous peoples of the New World.

Antiquity and Origins of the Mushroom Cult

It can of course be argued that the two great mushroom traditions, that of New World Indians and that of the peoples of Eurasia, are historically unconnected and autonomous, having arisen spontaneously in the two regions from similar requirements of the human psyche and similar environmental opportunities. But are they really unrelated?

A good though controversial case has been made by some prehistorians for sporadic early contacts across the Pacific between the budding civilizations of the New World and their contemporaries in eastern and southern Asia, perhaps as early as the second millennium B.C. The West, until very recently, consistently underrated the maritime capabilities of the early Chinese, whose ships more than 2000 years ago were not only already considerably larger and more seaworthy than those of medieval Europe but were equipped with an effective rudder of a type adopted by the Europeans only shortly before Columbus embarked on his first voyage of discovery. Moreover, it was the Chinese who invented the compass. So we must at least grant them the potential of having crossed the Pacific, whether they ever did so or not. Now if, as seems likely, the Chinese once worshiped an hallucinogenic mushroom and employed it in religious ritual and medicine,* and if some of their sages reached the New World, by accident or design, they could of course have introduced some of their own advanced pharmacological knowledge, or at least the idea of sacred mushrooms, to the ancient Mexicans. The same would apply to early India, whose calendrical system, like that of China, bears a perplexing resemblance to its pre-Hispanic Mexican counterpart. But these are very big ifs indeed.

Considering the proven antiquity of hallucinogens in the New World, it seems more reasonable to refer back to La Barre's argument and consider the problem in the context of the ecstatic-shamanistic phenomenon as a whole. The roots of the New World mushroom complex, as of the other ritual hallucinogens, would then have to be sought in a common pan-EurasiaticAmerican Paleo-Mesolithic substratum, predating not just the evolution of advanced transoceanic sailing capabilities in ancient China or southern Asia, but even the first peopling of the New World. In that case, we could see the sacred mushroom of Paleo-Siberian tribes as prototype for all the ritual hallucinogens that proliferated so spectacularly among New World Indians, and the sacred mushrooms of Middle America as linear descendants of the fly-agaric.

This approach is the more plausible in that Wasson himself has traced some of the common names for the fly-agaric in Indo-European languages to Proto-Uralic, which ceased to be spoken around 6000 B.C. (the Proto-Uralic term was *panx, ancestral to the Ob-Ugricpango, the Gilyakpangkh, as well as our fungus or punk). The seventh millennium B.C. is obviously substantially later than the major movements of the proto-American hunters who carried their north Asian intellectual and material heritage from Siberia to Alaska across the Bering land connection, the thousand-mile-wide corridor of low-lying tundra that was submerged when the sea level rose by 200-300 feet with the melting of the Pleistocene glaciers about 12,000 years ago.

But old though it is, we might imagine that Proto-Uralic was probably still a language of the distant future when the psychodynamic properties of the flyagaric were first discovered by some venturesome shaman of an unknown Paleo-Eurasiatic hunting people exploring his environment not only for medicinal species but also for plants capable of transporting him to different, non-ordinary, planes of existence.

Discovery of Hallucinogens: Deliberate or Accidental?

Which brings up a point that was raised in the Introduction in relation to the plant hallucinogens in general: it is almost impossible to conceive that the discovery of the transformational qualities of certain acrid mushrooms that were clearly unsuitable as ordinary food could have been anything but the result of conscious search for psychodynamic agents and even deliberate experimentation for different ways to activate or heighten their effects. As we saw, this requirement applies especially to the fly-agaric, since it was dried, preferably in the sun, to have the desired effect.

That the Mexican mushrooms, on the other hand, can be eaten fresh* could, I suppose, mean that their magical properties were accidentally discovered when people already accustomed to wild mushrooms in their diet tried them as food. Perhaps so. Certainly it could have been the case in some very remote, primordial time. But to suppose this of the ancestors of the Indians of Oaxaca, one would have to conjure up a vision of the most primitive kinds of humans scavenging almost indiscriminately for anything that appeared edible—a picture that squares with absolutely nothing we know of the food-gathering behavior of the most technologically primitive hunters still left on earth and even less of incipient cultivators. Moreover, an environment in which mushrooms grow is not likely to have been deficient in all kinds of edible resources with far greater food value than the characteristically small and fragile sacred fungi.

What we must also remember is that traditional or pre-industrial people who live in harmony with their environment are the inheritors of a far more sophisticated level of knowledge than ours of the natural world on which their lives depend, and that they discriminate much more decisively and often more accurately than do we between its different phenomena. In the present case this reminder implies that ordinary and magic mushrooms should not even belong to the same category. And that is precisely the situation as we find it among present-day Indians.

As mentioned earlier, the Matlatzincas, who live about a hundred miles southwest of Mexico City, in a valley surrounded by pine forests and towered over by the majestic 15,000-foot-high Toluca volcano, have recently been added to the growing list of sacred-mushroom-using populations. Ordinary wild species also figure importantly in their diet, so that they would certainly fall into Wasson's category of "mycophiles." However, the sacred fungi and ordinary kinds are not simply lumped together under an all-embracing category of "mushroom." Rather, the hallucinogenic species is considered entirely separately, being grouped with such supernatural phenomena as God, the Virgin Mary, saints, ancestors, mountain spirits, and the like.

The Matlatzincas' highly complex mushroom taxonomy has been studied in detail by the Mexican linguist Roberto Escalante, and I am indebted to him for the data that follow. (Also see Escalante, 1973; Escalante and Lopez, 1971.)

To the Matlatzincas, as to other Indians of Mesoamerica, edible mushrooms are of great dietary importance because they sprout during periods of scarcity, when the maize is growing in the fields but when it is still too early for the harvest. During the rainy season, when little work is required in the fields, mushroom gathering involves the entire family, regardless of sex or age, so that it is essential that the criteria of identification be thoroughly familiar to everyone.

A Mexican Indian Mushroom Taxonomy

No less than 57 different species or varieties are distinguished, named, and classified down to the last detail, including external characteristics and extending even to specific use or uselessness of each variety. Two principal nonhallucinogenic groups are recognized, one identified by the generic prefix xi (the smuts), the other by chho , followed by more specific phrases or terms that identify the species respectively by habitat, color, form, texture, similarity to other objects, and the like—for example, Green Mushroom of Maize, Mushroom (like) Gourd, Mushroom of the Birch. The Matlatzincas also know exactly which species are "companions"—i.e. sprout at the same time—which can contribute to identification where an edible species closely resembles a poisonous one. Over-all, mushrooms are considered to be formed of three parts—the cap, called "its little face," the stem or stalk, "its little foot," and the gills, "its inside," although some species utilized by the Matlatzinca may, like the puffballs, be recognized as consisting only of the "little face." In any event, in order to identify the mushrooms the Indians first observe the whole, then the "little face," then "the little foot," and finally the interior. Needless to say, such careful observation is especially important where an edible species is closely related and similar to a dangerously toxic one, as in the case of the edible Amanita species.

Now, in contrast to the edible species identified by the generic prefixes xi or chho, meaning mushroom, the sacred hallucinogenic species, Psilocybe muliercula—which are gathered near the river bank and which must always be replaced by an offering of wild flowers—are not called "mushroom" at all but are identified as divine personages: ne-to-chu-tata = (dear) little sacred lords, or, in Spanish, santitos, literally saints but also signifying ancestors, divine ancient ones, and the like.*

Matlatzinca mushroom taxonomy, which places edible mushrooms in one category and the hallucinogenic kind into a wholly different metaphysical one, alongside deities and spirits, illustrates not only how thorough must be knowledge of the plant world when survival itself depends on it, but also that we must not assume a functional relationship between mushrooms in the daily diet and mushrooms as divine beings or mediators between man and the supernatural. To most of us, all mushrooms, sacred or culinary, may look more or less alike, but to the Indians they are wholly different experiential phenomena.

Hallucinogenic Mushrooms North of Mexico

As a matter of fact, the ethnographic and ethnobotanical situation in North America proves just that. While we have as yet no conclusive evidence that any kind of psychoactive mushroom was employed by Native Americans north of Mexico, however important edible mushrooms might have been to their diet, it is a fact that, as was noted in a previous chapter, a number of varieties containing psilocybine and other hallucinogenic compounds occur in North America, including species of Psilocybe. Moreover, as La Barre (1970c) has pointed out, the flaming-red variety of Amanita muscaria—the sacred species of the northern Eurasians—is native not only to Asia and Europe but to British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and Colorado, as well as the Sierra Madre of Mexico. The yellow variety occurs elsewhere in North America, including the northeast, especially in coniferous and birch forests—precisely the favorite habitat of Amanita muscaria also in the Old World.

We shall never know whether any memory of its wondrous properties remained with the first Americans to encounter the fly-agaric in their new northern environment, or indeed if any of their descendants ever tried it.

There is no direct mention of fly-agaric use in any of the oral traditions of which we have records. Yet in historic times the urine of shamans was considered to possess great magical and therapeutic powers by some of the Northwest Coast tribes; shamans preserved their urine carefully in containers reserved for that purpose and employed it to guard themselves and others against malevolent beings, by such techniques as blowing it through tubes in the direction of supernatural danger. Alaskan Eskimos, whose culture originated in Siberia some 13,000 years ago, likewise respect urine for its magical properties, and hold the bladder in high regard as the seat of special powers. Could such beliefs be survivals of a more ancient fly-agaric urine-drinking tradition?

If so, all knowledge of it has certainly long been lost, while in Mexico Amanita muscaria's Eurasiatic role as the mushroom of divine knowledge was assumed—when, we do not know—by fungi of very different appearance and pharmacology.

What we do know is that when the hunters of bison and mammoth in the Late Pleistocene reached and settled the country of the Rio Grande, they also discovered a new ritual inebriant, the highly toxic, red beanlike seed of Sophora secundiflora, which their descendants were to employ for the next 10,000 years in ecstatic-shamanistic medicine cults, until autonomous Indian culture succumbed to Anglo-American expansionism and the more benign peyote was adopted as the sacrament of a new, syncretistic pan-Indian religion.

*As the threefold fire god—earthly fire, lightning, and solar fire—Agni is second only to Indra in ancient Vedic and Hindu worship. He is the offspring of the vertical and horizontal sticks of the fire drill, sometimes called Agni's "two mothers." The Vedic word Agni is cognate to the Latin ignis = fire, and of course also to the English ignite.

*Wasson (1968:80-92) makes a persuasive case that the celebrated Ling Chih, the supernatural fungus of immortality and spiritual potency, endlessly represented in Chinese art from early times, had its genesis in the Eurasiatic cult of the divine hallucinogenic mushroom—i.e. Soma = Amanita musearia—even through its abundant artistic forms came to be based on Ganoderma lucidum, an inedible species of woody fungus.

*As was pointed out to me by Wasson, anciently a common method of consuming the sacred mushrooms was to press them out and drink their juice--i.e., the same way Soma was taken in Asia. However, they could also be eaten raw, often with honey, as indeed they often are today by Mexican Indians.

*Ne-to-chu-tizta, it is said, will diagnose the cause of the illness and prescribe the medicine, and even give a massage to the afflicted organ. Beautiful visions are also reported, including flowers, stars, and gardens, as well as terrible ones, such as blood oozing from cornstalks, serpents, skeletons, and dismembered bodies. The last is especially significant in that visions of dismemberment and skeletonization are related by the Matlatzincas—as by other traditional peoples—to shamanic initiation.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|