CHAPTER THIRTEEN: HALLUCINOGENIC SNUFFS AND ANIMAL SYMBOLISM

| Books - Hallucinogens and Culture |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: HALLUCINOGENIC SNUFFS AND ANIMAL SYMBOLISM

Thus far we have encountered deer, jaguars, birds, snakes and toads in relation to the sacred hallucinogens, either in some symbolic association, or in the imagery of the ecstatic trance, or even as avatar of a particular plant. Animal symbolism is clearly inseparable from the traditional psychedelic complexes of the Old and New Worlds, and its investigation of great culture-historical and psychological interest. These final chapters will concern themselves with some of these questions, and they will lead us in some surprising directions.

But I want to back into that fascinating arena by returning once more to the potent snuffs that greeted the early Spanish explorers as the first manifestation of the New World hallucinogens. For it is above all in the technology and symbolism of snuffing that a whole complex of animal imagery manifests itself in archaeological and ethnographic art.

In considering the major hallucinogenic snuffs, we should not forget that many of the scores of psychoactive plants of the New World could at least theoretically be used in this way, and that especially in South America there is much evidence for such experimentation. Even Ilex guayusa, the caffeine-containing holly that, along with its sister species, is widely utilized as a stimulating tea (e.g., mate = I. paraguayensis), served as snuff, at least for some shamans of ancient highland Bolivia, judging from a recently excavated shaman's grave dated to ca. A.D. 500, that contained bundles of hex leaves together with a complete kit for preparing and taking snuff. The kit also includes clysters, so that the same plant might even have been employed as enemas (Schultes, 1972b).

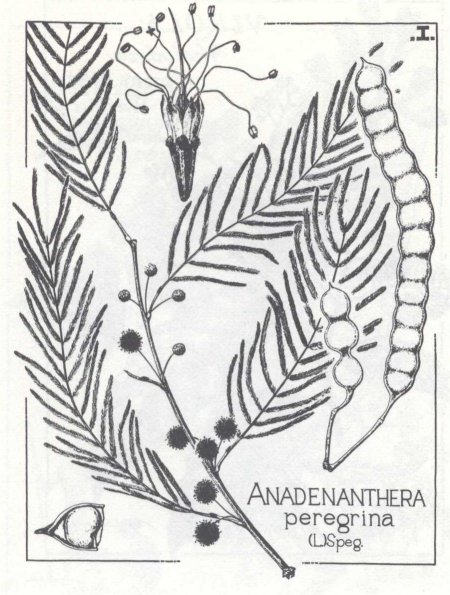

The principal snuffs are now well known, their botany and chemistry having at last emerged from a long period of taxonomical confusion and uncertainty. At first, as was mentioned earlier, tobacco was thought to be the source of the hallucinogenic snuff of the West Indies. Then, for a long time—in fact, until just a few years ago—all intoxicating snuffs, from the Antilles through much of South America, were almost uniformly ascribed to one species of Piptadenia, P. peregrina, closely related to the acacias and mimosas. Now, thanks to plant taxonomist Sin i von Reis Altschul (1964, 1972), a student of Schultes, P. peregrina has been removed from that genus and reclassified as one of two species belonging to a new, related, but clearly distinct hallucinogenic genus, Anadenanthera. The other is A. colubrina, a western South American species that is the source of the sacred huilca (wilka) seeds of the Andes, which were variously employed in the form of snuff, infusions, and even enemas.

The Virola Tree as a Source of Snuff

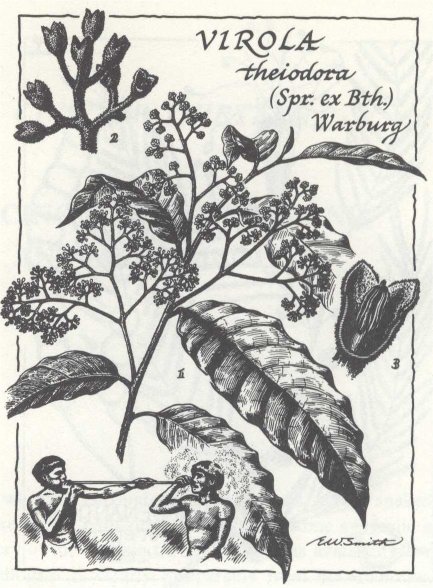

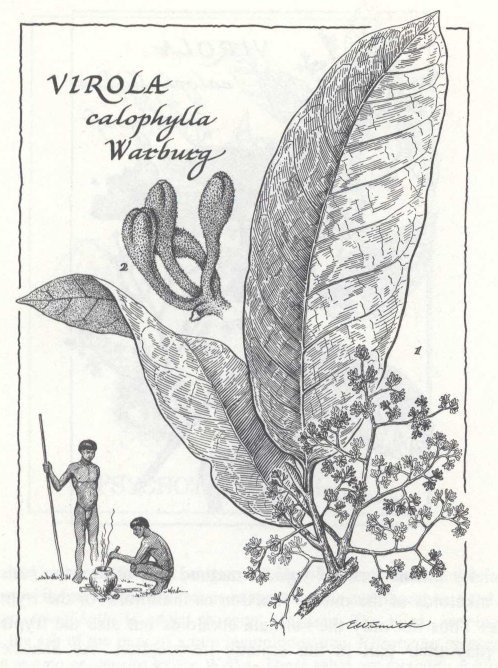

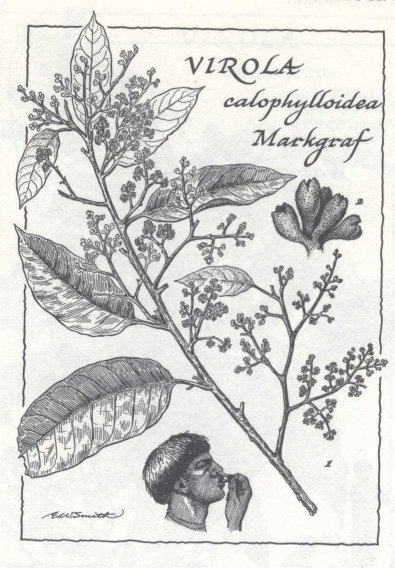

But even this corrected classification did not clear up all the confusion, because snuffs were attributed by many writers to Anadenanthera, whether or not that genus actually occurred locally, and even though the observed method of preparation suggested that several different and even unrelated species might be involved. The mystery was cleared up when several species of Virola, a tree belonging not, like Anadenanthera, to the Leguminoseae (pea family) but, like nutmeg, to the Myristicaceae, were confirmed as source of some of the snuffs once attributed solely to A. peregrina. Schultes was again prominently involved in settling this problem.

The principal hallucinogenic alkaloids in both Anadenanthera (peregrina and colubrina) and in the several species of Virola (V. theidora , V. callophylla, V. callophylloidea) are tryptamines, as they are also in one species of Banisteriopsis , and in the sacred mushrooms and other ritual hallucinogens of Mexico. In A. peregrina and colubrina, bufotenine (5-hydroxy-N,Ndimethyltryptamine) is present in large amounts, and for a time the central nervous activity of Anadenanthera snuffs was thought to be due mainly to this alkaloid, which these leguminous trees share with the toad (Bufo spp.). Recent analyses have shown, however, that other tryptamine derivatives are also present in the seeds—such as N,N-dimethyltryptamine, N-monomethyltryptamine,5-methoxy-N, 5-methoxy-N-monomethyltryptamine, N,N- dimethyltryptamine-N-oxide,5-hydroxy-N, and N-dimethyltryptamine-Noxide (Schultes, 1972a:28).

Snuff prepared from Virola theidora alone, without admixtures, contains 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine in concentrations of up to 8 percent, along with smaller amounts of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and related alkaloids. Alkaloid concentrations vary in different parts of the tree, but the bark generally contains the highest percentage.

Now, as we know, tryptamines require a monoamine oxidase inhibitor to become effective in man, a problem the Indians have solved in several known instances by mixing different hallucinogenic species together. For example, Banisteriopsis rusbyana is a chemical oddity among its sister species, in that in contrast to B. caapi and B. inebrians, whose active principles are betacarboline hannala alkaloids, its active constituents are tryptamines! This explains why the Tukanoan Indians of Colombian Amazonia, for example, never take B. rusbyana by itself but mix it with B. caapi or B. inebrians into an especially potent form of yaj, a method that allows the beta-carboline harmala alkaloids of the one to function as inhibitors for the tryptamines of the other. Thus not only the harmala alkaloids but also the tryptamines are able to play their part in the ecstatic intoxication. As Schultes (1972a) observes, here again one cannot help but wonder

how peoples in primitive societies, with no knowledge of chemistry or physiology, ever hit upon a solution to the activation of an alkaloid by a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. (p. 38)

Now, in the case of Virola snuffs, no such activating admixture seems to be absolutely required, since two new carbolines have recently been discovered in V. theidora itself (Schultes, 1970). Nevertheless, admixtures that can themselves be psychodynamically effective are frequently employed. Schultes (1972a), who visited the Waika (Yanomam6) in 1967 with the Swedish pharmacologist Bo Holmstedt, describes their technique as follows:

There are a number of methods of preparing the snuff, which is called epena or nyakwana by the many "tribes" which I include under the generic term Waika. Some scrape the soft inner layer of the bark of the tree, dry the shavings by gentle roasting over a fire, and store them until they are needed for making the snuff. They are then crushed and pulverized, triturated and sifted. The resultant powder is fine, homogeneous, chocolate-brown, and highly pungent. Then, when the Indians desire it (but not always) a dust of the powdered dry leaves of the aromatic acanthaceous weed Justicia pectoralis var. stenophylla is added in equal amounts. The third, and invariable, ingredient is the ash of the bark of a rare leguminous tree, Elizabetha princeps. This tree is known as ama or amasita by the Waika. These ashes are mixed in approximately equal amounts with the resin, or resin and Justicia powder, to give a brownish-grey snuff.

Other Waikas follow a different procedure, at least when they are preparing the snuff for ceremonial purposes. The bark is stripped from the Virola tree, the strips laid over a gentle fire in the forest, and the copious blood-red resin is scraped into an earthenware pot. It is boiled down and allowed to sun-dry. Then, alone or mixed with the powdered Justicia leaves, it is sifted and is ready for use. (p. 43)

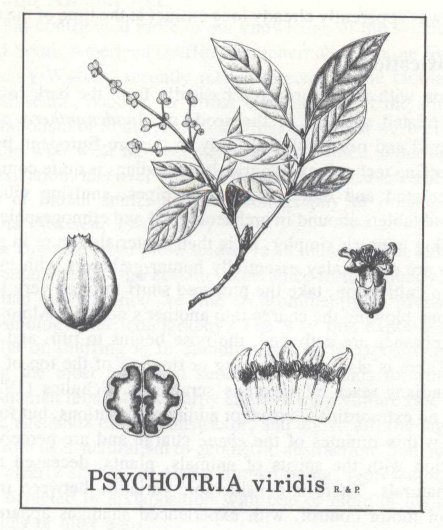

J. pectoralis appears to be itself a potent hallucinogen, containing, like Virola, tryptamine alkaloids. It is in fact cultivated by some of the Yanomamo groups studied by anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon and his colleagues on the Upper Orinoco and employed without any active admixtures in one variety of intoxicating ebene snuff (Chagnon et al., 1971). (It should be noted here that Justicia and another tryptamine-containing South American genus, Psychotria, occur also in Mexico, a circumstance to which I will return in connection with the recent discovery of a very ancient snuffing complex in Mexico that was apparently already long extinct at the time of the Conquest.)

Rapid Intoxication

Intoxication with snuffs prepared basically from the bark resin of Virola theidora or related species, or the seeds of Anadenanthera peregrina, is extremely rapid and powerful. Not only in the pre-European past but even today the snuffing technology of agricultural Indians is quite complex, and all sorts of decorated and undecorated nose pipes, snuffing tubes, mortars, containers and tablets abound in archaeological and ethnographic collections. Waika snuffing is much simpler, as is their material culture in general. The Waika, who are even today essentially hunter-gatherers with incipient tree-and root-crop cultivation, take the prepared snuff through very long bamboo tubes, one man blowing the charge into another's nostrils. Almost at once the mucous membranes are activated, the nose begins to run, and saliva flows copiously. There is also strong itching or tingling of the top of the skull, to which the Indians react by vigorous scratching. Schultes (1972a) himself experienced no extraordinary visual or auditory sensations, but for the Indians these occur within minutes of the ebene charge and are perceived as direct communication with the spirits of animals, plants, deceased relatives and other supernaturals. There is considerable variation between individuals in the degree of motor control, with experienced shamans apparently able to exercise much greater control over their movements than others. The intensity of the ecstatic trance also varies; the experience is usually of short duration, however, and in the course of ritual (and, nowadays, among more acculturated Waika, also recreational) intoxication repeated charges of snuff are customarily inhaled by the participants.

Addiction: Snuff, No; Tobacco, Yes

In light of the frequency with which these powerful tryptamine preparations are employed and the intensity of the experience, it is worth quoting the following observation:

. . none of the hallucinogens used by the Yanomam6 are habit-forming, missionary opinions notwithstanding . . . Yanomamo can and do abstain from them for weeks and do not mention it or complain about it. Tobacco-chewing, on the other hand, is habitual: they cannot go several hours without it, and the entire village is in a state of crisis when the tobacco crop fails. In this connection the Yanomamo have discovered a number of tobacco substitutes, from both domestic and feral plant sources, to rely on when they run short of tobacco. When questioned on the possible substitutes for their hallucinogens, one informant summarized the drug-tobacco situation as follows:

"When we are out of tobacco we crave it intensely and we say we are h5ri—in utter poverty. We do not crave ebene in the same way and therefore never say that we are "in poverty" when there is none. But yakoana (Virola) is everywhere, and we can always find some if we want to take ebene." (Chagnon et al., 1971:74)

Snuffing and Animal Art

No one has contributed more to our knowledge of the symbolic content of Central and South American snuffing paraphernalia than the Swedish ethnologist S. Henry Wassen, recently retired director of the Gothenburg Ethnographical Museum. Wassen, to whose early studies of the ethnopharmacology and symbolism of South American frogs and toads we will shortly return in connection with what has recently been discovered about toad- and frog-poison intoxication, has over the past decade published several major studies on the use of Indian snuffs and the iconography of ornamented snuffing paraphernalia (Wassen, 1963-1967).

What has emerged from these studies is an unmistakable symbol complex that ties shamanism and the ecstatic experience to the already familiar birdfeline-reptilian configuration we find so prominently in Mesoamerican and Andean cosmology and iconography. The way this expresses itself in the paraphernalia of snuffing is in combinations or juxtapositions of elements representing the most important supernatural animals to which the South American shaman relates—the harpy eagle or king vulture (the condor in the Andes), the anaconda or boa constrictor, and above all, the jaguar, in styles that range from near-naturalism to geometric abstraction. Sometimes only one of these is clearly shown, or else a human being, representing the shaman himself, is depicted in juxtaposition with one or more of his principal zoomorphic allies or alter egos.

On occasion the complementary opposition of the bird and jaguar, or birdjaguar-serpent, is symbolized not in the form of a two- or three-dimensional image but rather in the materials employed in the making or ornamentation of the implements—e.g. bird-bone snuffing tube juxtaposed with wooden snuff trays decorated with feline and snake motifs or else bird feathers and snake skin used as symbolic adornments (see Wassen, 1967, for numerous illustrations of these motifs).

The juxtaposition of bird and mammal in the material culture of snuffing has a respectable pedigree, since it is already evident in the oldest snuff paraphernalia thus far known—a bone tray and tubes which Junius B. Bird of the American Museum of Natural History excavated in the ancient Peruvian coastal site of Huaca Prieta, and which are dated to about 1600 B.C.

The point is that analogous arrangements of certain animals and human beings in the symbolic art of the snuffing complex are not limited to one region or one period but extend through space and time from the Caribbean to the Andes and from prehistory to the present.

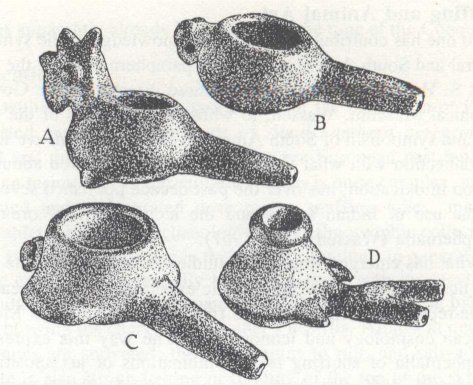

Bird-shaped snuffing pipes. Fired-clay objects from archaeological sites in Costa Rica. A. Guanacaste; B-D, Linea Vieja. Average length, 5-6 inches. Collection of the Gothenburg Ethnographic Museum. Drawing courtesy of S. Henry Wassen.

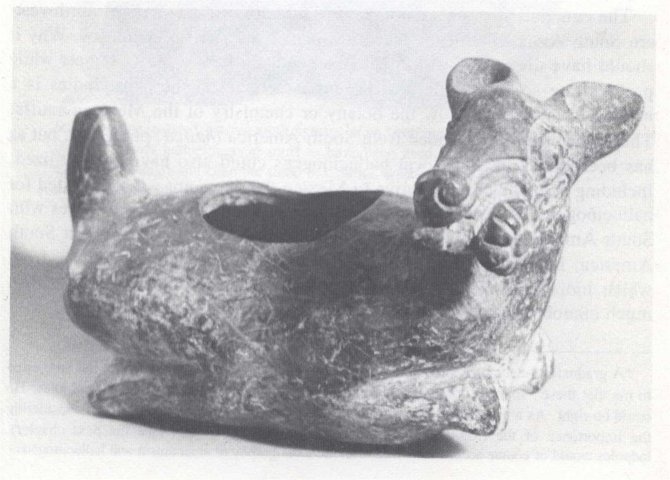

Of special interest are decorated snuff containers, mortars, tubes, nose pipes, and related implements that depict the jaguar as guardian or alter ego of the shaman—a dominant theme, we recall, in tropical American shamanism that can be recognized in archaeological snuffing paraphernalia from Argentina and Chile as well as Mesoamerica (Wassen, 1967; Figures 8, 11, 13-14, 30-31). Not surprisingly we also find it symbolized in other artifacts connected with the practice of shamanism.

Quite apart from the frequent resort to bird bone for snuffing tubes (a choice that must have been motivated at least as much by symbolic as by practical considerations), the avian motif predominates also in the representational or abstract art of the snuffing complex. Where the bird motif is specific, it usually represents the harpy eagle or its Andean cousin, the condor, or else some other bird selected for special characteristics that relate it symbolically to the phenomenology of shamanism. Typically these birds include waterfowl or diving birds, presumably because their unique ability to transcend the boundaries of different planes of existence is seen to be analogous to that of the shaman. As a matter of fact, it is axiomatic of shamanic symbology that it selects precisely those animals that can shift between different environments or that by virtue of unusual life histories or habits are perceived as mediators between disparate states. Where the bird motif is unspecific, it seems to stand for the power of flight that is the shaman's special gift and that is activated by the hallucinogen. It should also be noted that birds are often regarded as guardian spirits or even manifestations of specific psychoactive plants, especially tobacco; this observation provides one clue for the meaning of bird-shaped tobacco pipes in North American Indian art. Among the many known archaeological examples of the bird motif in snuff paraphernalia are numerous nose pipes of fired clay from archaeological sites in Costa Rica and a series of small bird-shaped polished stone mortars from ancient shell middens on the coast of Brazil. (See Wassen, 1967: Figures 4 and 12. Figure 34 in the same publication depicts some interesting wooden or bamboo snuffing tubes from several South American localities with nose pieces shaped like bird's heads, which make them resemble the well-known bird-headed staffs associated with shamanism as symbols of the shaman's tree and his ascent to the Upperworld. Such a staff was also found in the shaman's burial in highland Bolivia. (Schultes, 1972b)

Snuffing in Mexico

Now we give attention to Mexico and the archaeological evidence for an ancient snuffing complex that dates back at least to the second millennium B.C., apparently became extinct as a major technique of ritual intoxication before A.D. 1000, and today survives only in remote mountain areas of Oaxaca and Guerrero, where some curers are said to inhale the pulverized seeds of the morning glory (T. Knab, personal communication, based on the unpublished field notes of the late botanist Thomas McDougall). It has always seemed puzzling that the early Spanish missionaries, who were certainly alert to the many manifestations of ritual intoxication, seem not to have seen any evidence of snuffing, even in areas adjacent to the well-developed snuffing complex of the Caribbean island cultures. Powdered tobacco is mentioned, but there is nothing to suggest that it, or any other hallucinogen, was inhaled as snuff.

Deer, holding peyote cactus in its mouth. A snuffing pipe about 2500 years old, from Monte Alban, Mexico. Length 5 inches; private collection.

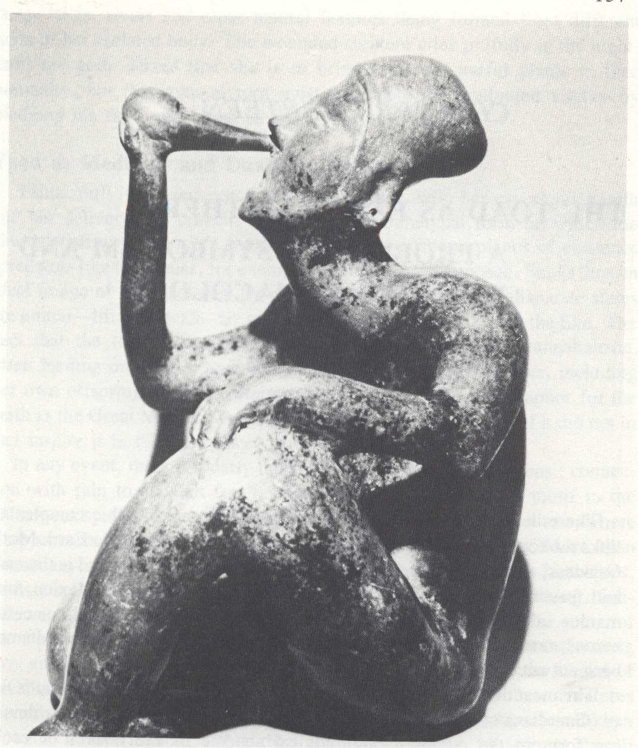

The negative evidence from the sixteenth century notwithstanding, Mexico once did have a well-developed snuffing complex (Furst, 1974b). Individuals holding nose pipes to their nostrils are depicted in trance-like states in Colima mortuary art from western Mexico, dated ca. 100 B.C.-A.D. 200. Also, there are in the archaeological art of Oaxaca numerous small ceramic effigy bowls with short, perforated stems, dating from 500 B.C. to the first centuries A.D. Their purpose becomes obvious once one knows that snuffing was practiced: they are not "sacrificial" or "libation" bowls, as they are often described, but nose pipes, decorated with such typically shamanistic themes as flight and transformation.

The earliest Mesoamerican ceramic nose pipes, dating to about 1300-1500 B.C., were found at Xochipala, Guerrero, in association with finely made figurines of men and women in a remarkably sophisticated and naturalistic style. Among the Xochipala snuffers from this early site, one simple bowl with a hollow stem is virtually indistinguishable from many that have been found in Costa Rica. So also is a double-stemmed bird-effigy nose pipe from a deep shaft-and-chamber tomb in Nayarit, dated ca. A.D. 100.

Finally, there are the famous Olmec jade artifacts, nicknamed "spoons," that could have served as snuff tablets. Some of these finely carved and highly polished objects, sometimes decorated with incised bird-jaguar motifs in the typical Olmec style of 1200-900 B.C., resemble, with their long tails and slightly rounded bodies, stylized profile birds in flight—symbolism that would fit comfortably into the animal art of hallucinogens, and especially the flight motif in the iconography of shamanic snuffing (Furst, 1968:162-63).*

The cumulative evidence points to a southern origin—perhaps northwestern South America—for the early Mesoamerican snuffing complex. Why it should have disappeared from Mexico centuries before the Conquest while proliferating so spectacularly in South America and the West Indies is a mystery. Nor do we know the botany or chemistry of the Mexican snuffs. They could have been traded from South America (huilca, perhaps?), but as has been noted, various local hallucinogens could also have been utilized, including acacia-like trees native to Mexico that have not yet been tested for hallucinogenic alkaloids. Apart from these possibilities, Mexico shares with South America not only tobacco, which was and is used as snuff in South America, but also at least one tryptamine-containing genus, Justicia, from which Indians on the Upper Orinoco make an intoxicating snuff. Clearly, much ethnobotanical and phytochemical work remains to be done.

*A graduate student specializing in Olmec iconography, Anatole Pohorilenko, has suggested to me that these "spoons" may represent not conventionalized birds in flight but tadpoles. He could be right. As a transitional stage in an ongoing process of metamorphosis, and considering the importance of the frog/toad motif in Mesoamerican symbolism (see the next chapter), tadpoles would of course accord very well with the iconography of shamanism and hallucinogens.

Snuffing pipe in use. Ceramic tomb figurine of an "entranced" man with a snuffing pipe shows hallucinogenic snuff to have been used in Mexico 2000 years ago. From a shaft-and-chamber tomb in Colima, western Mexico, ca. 100 B .C.- A.D. 200. Height 10 inches. Collection of Kurt Stavenhagen, Mexico.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|