CHAPTER ELEVEN*: "TO FIND OUR LIFE": PEYOTE HUNT OF THE HUICHOLS OF MEXICO

| Books - Hallucinogens and Culture |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER ELEVEN*: "TO FIND OUR LIFE": PEYOTE HUNT OF THE HUICHOLS OF MEXICO

Wiriklita is typical Chihuahuan-type desert, with an average altitude of 5000 feet, covered with creosote bush, mesquite, tar bush, yucca, agave, and many other kinds of cactus. It does the Huichols no favor to pinpoint the peyote country more precisely than to say that it overlaps more or less with the old mining Real of Catorce in northwestern San Luis Potosi; as it is, we were told by a railroad crew close to the sacred mountains that the year before a group of bearded young men and their girls had pitched tents nearby and lived there for several weeks, harvesting and eating peyote. This intelligence disturbed RamOn greatly, because the cactus grows slowly and such mass consumption by non-Indians was bound to have serious consequences for the success of future peyote hunts by those to whom the little cactus is, quite literally, the "source of life." Between the Place of Our Mothers and the peyote country proper there were to be two more camps. The second was only ten miles (in this rugged desert, two hours' driving time) from the area Ramon had selected in his mind for the hunt of Elder Brother Wawatsari, the "Principal Deer," who is animal avatar of peyote. We broke camp before dawn, in bitter cold, waiting only for the first red glow in the east so that the pilgrims might pay their proper respect to the rising Sun Father and ask his protection. There was little conversation on this final stretch. Everyone remained still, except for the times when the vehicles had to be emptied of passengers to get past a particularly difficult spot in the trail. Even then there were few unnecessary words. Ramón's wife Lupe and her uncle Jose lit candles the moment we started out and held them the entire distance.

A Time to Walk

It was just past 7:00 a.m. when Ramon stopped the cars and told the Indians to get out and assemble in single file by the side of the trail. It was time to walk. For no matter how one had traveled thus far, one must enter and leave the "Patio of the Grandfathers" exactly as had Tatewarl and his ancient pilgrims—on foot, blowing a horn and beating the hunting bow. In former times, and occasionally today, the horn was a conch shell; Jose's was goat horn, and one of the others used a cow-horn trumpet.

As the hikuri seekers walked they picked up bits of dry wood and branches of creosote. Little Francisco, age ten, who was carrying his two-year-old brother, stopped to break off a green branch for himself and also stuck a long dry stick in the little boy's hand. This was the food of Tatewari. It is another mark of the total unity of the hikuritamete (peyoteros) that each companion, down to the youngest, is expected to participate in the first "feeding" of the ceremonial Fire when it is brought to life by the mara'akáme.

This happened so quickly that we almost missed it. The line stopped, Ramon squatted, and seconds later there was a wisp of blue smoke and a tiny flame. Tatewarl had been "brought out" (fire is inherent in wood and only needs "bringing out"). Now more than at any other time on the pilgrimage, speed and skill in starting the fire are of the essence, for one is in precarious balance in this sacred land and urgently requires the manifestation of Tatewari for protection. The fire is allowed to go out only at the end, when sacred water is poured on the hot ashes, after which the mara'akme selects a coal, the kuptiri (soul, life force) of Tatewari, and places it in the little ceremonial bag around his neck. Since the ritual is repeated at each campsite there is an accumulation of magic coals, which become part of the mara'akme's array of power objects.

Food for Grandfather

Chanting and praying, Ramon piled up bits of brush which quickly caught fire. The others, meanwhile, arranged themselves in a circle with their pieces of firewood and began to pray with great fervor and obvious emotion. We saw tears course down Lupe's face, and there was much sobbing also among the others. Such ritualized manifestations of joy mixed with sorrow were to recur several times during our stay in Wiriküta, especially at the successful conclusion of the "hunt," and again when we were getting ready to take our final leave. After much praying, chanting, and gesturing with firewood in the sacred directions, and a countersunwise ceremonial circuit around the fire, the individual gifts of "food" were given to Tatewarl and everyone went off to prepare for the crucial pursuit of the Deer-Peyote.

It was midmorning when Ramon signaled the beginning of the hunt. To my question how far we would have to walk to find peyote, he replied, "Far, very far. Tamatsi Wawatsâri, the Principal Deer, waits for us up there, on the slopes of the mountain." I judged the distance to be about three miles.

Everyone gathered up his offerings and stuffed them in bags and baskets. Bowstrings were tested. Catarino Rios, the personator of Tatutsi (Great-grandfather), one of the principal supernaturals, stopped playing his bow to help his wife Veradera (Our Mother Haramara, the Pacific Ocean) cut a few loose strings from the little votive design she had made from colored yarn on a piece of wood coated with beeswax, to be given as a petition to the sacrificed Deer-Peyote. The design depicted a calf. Catarino's bow music, we were told, was to make the deer happy before his impending death. Ramon conducted the pilgrims in another circuit around the fire, during which everyone laid more "food" on the flames and pleaded for protection. RamOn entreated Tatewari not to go out and to greet them on their return. Then he led the companions away from camp toward the distant hills.

The Ritual Kill

About 300 feet from camp we crossed a railroad track and beyond it a barbed-wire fence. The men had their bows and arrows ready. Everyone had shoulder bags and some had baskets as well, containing offerings. We had walked perhaps 500 feet when RamOn lifted his fingers to his lips in a warning of silence, placed an arrow on his bowstring, and motioned to the others to fan out quickly and quietly in a wide arc. I pointed to the distant rise—was that not where we would find the peyote? He shook his head and smiled. Of course, I had forgotten the reversals of meaning that are a part of ritual language on the peyote pilgrimage. When he had said, "Far, very far," he really meant "very close." Ramon now crept forward, crouching low, intently watching the ground. Catarino's bow, which he had sounded by beating the string with an arrow along the route "to please Elder Brother," fell silent. The women hung back. Ramon halted suddenly, pointed to the ground, and whispered urgently, "His tracks, his tracks!" I could see nothing. Jose, personator of Tayaupa, Sun Father, sneaked up close and nodded happy assent: "Yes, yes, mara'akáme, there amid the new maize, there are his tracks, there at the first level." (There are five conceptual levels, corresponding to the four cardinal points—east, south, west, and north, with zenith and nadir combined into a single fifth direction rather than being counted separately as among the Zuni. For a man to reach the fifth level, as Ramon was to do here in Wiriküta, means he has "completed himself"—i.e., become shaman.) The "new maize" was a sad little stand of dried-up twigs. The hunters look for any growth that can be associated with stands of maize, for the deer is not only peyote but maize as well. Likewise, peyote is differentiated by "color," corresponding to the five sacred colors of maize—blue, red, yellow, white, and multicolored.

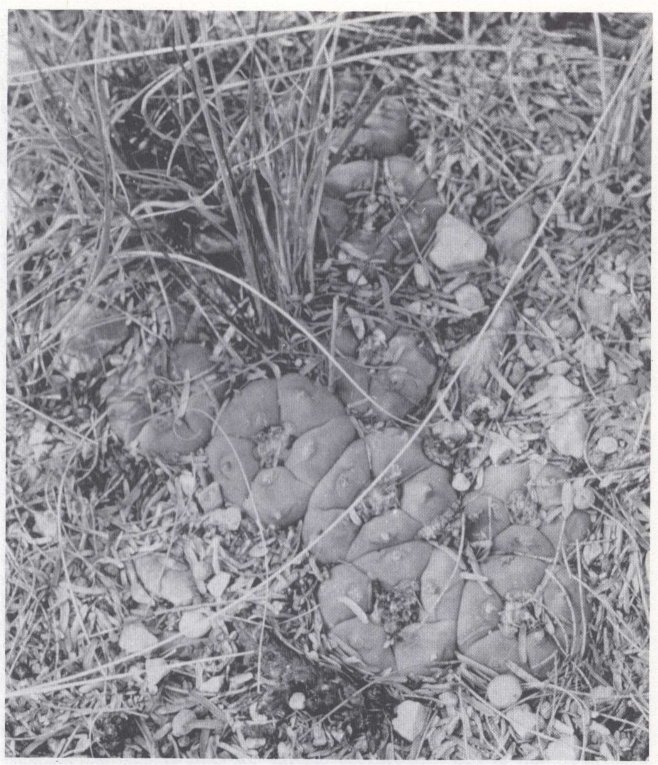

"There, there, the deer!" A clone of peyote, the gray-green crowns barely extending above ground. Photographed in the north-central desert of Mexico.

Ramon moved forward once more, Jose following close behind and to one side, his face lit up with the pleasure of discovery and anticipation. All at once Ramon stopped, motioning urgently to the others to come close. About 20 feet ahead stood a small shrub. He pointed: "There, there, the Deer!" Barely visible above ground under the bush were some flecks of dusty green—evidently a whole cluster of Lophophora williamsii . Although I have seen peyote plants growing in full sunlight, more often it is found like this—in a thicket of mesquite or creosote, shaded by a yucca or Euphorbia (especially Euphorbia antisyphilitica), or close to some well-armed Opuntia cactus, such as rabbit ear or cholla. Its broad, flat crown is usually almost level with the earth and so is easily missed by the inexperienced eye).

Ramon took aim, and the first of his arrows buried itself a fraction of an inch from the crown of the nearest hikuri. He let fly with a second, which hit slightly to one side. Jose ran forward and fired a third, almost straight down. Ramon completed the "kill' by sticking a ceremonial arrow with pendant hawk feathers into the ground on the far side, so that the sacred plant was now enclosed by arrows in each of the world quarters. The mara'aectme bent down to examine the peyote. "Look there," he said, "how sacred it is, how beautiful, the five-pointed deer!" Remarkably, every one of the peyotes in the cluster had the same number of ribs—five, the sacred number of completion! Later on, Ramon was to string a whole series of "five-pointed" peyotes on a sisal fiber cord and drape it over the horns of Kauyumarie mounted on the vehicles.

The companions formed a circle around the place where Elder Brother lay "dying." Many sobbed. All prayed loudly. The one called Tatutsi, Great-grandfather, unwrapped Ramón's basket of power objects, the takwatsi, from the red kerchief in which it was kept and laid it open for Ramón's use in the complex and lengthy rituals of propitiation of the dead deer (peyote) and division of its flesh among the communicants. Ramon explained how the kupltri, the life essence of the deer, which, as with humans, resides in the fontanelle, was "rising, rising, rising, like a brilliantly colored rainbow, seeking to escape to the top of the sacred mountains." "Do not be angry, Elder Brother," Ramon implored, "do not punish us for killing you, for you have not really died. You will rise again." Ramon was echoed by the pilgrims. "We will feed you well, for we have brought you many offerings, we have brought you tobacco, we have brought you water from Our Mothers, we have brought you arrows, we have brought you votive gourds, we have brought you maize and your favorite grasses, we have brought you tamales, we have brought you our prayers. We honor you and we give you our devotion. Take them, Elder Brother, take them and give us our life. We offer our devotion to the Kakauyarixi who live here in Wiriküta; we have come to be received by them, for we know they await us. We have come from afar to greet you."

A Huichol Communion

To push the rainbow-kupitri, which only he could see, back into the Deer, Ramon lifted his muvieri (shaman's prayer arrow), first to the sky and the world directions, and then pressed it slowly downward, as though with great force, until the hawk feathers touched the crown of the sacred plant. In his chant he described how all around the dead deer peyotes were springing up, growing from his horns, his back, his tail, his shins, his hooves. "Tamatsi Wawatsári," he said, "is giving us our life." He took his knife from the basket and began to cut away the earth around the cactus. Then, instead of taking it out whole, he cut it off at the base, leaving a bit of the root in the ground. This is done so that Elder Brother can grow again from his "bones."* Ramon sliced off the tough bottom half of the cactus and peeled away the rough brown skin, carefully preserving the waste for ritual disposition later. Then he divided the cactus into five pieces by cutting along the natural ridges and placed these pieces in a votive gourd. The process was repeated by Ramon and Lupe with several additional plants, for there had to be enough to give each of the companions a part of "Elder Brother's flesh." Those who had made previous pilgrimages came first. One by one they squatted or knelt before Ramon, who removed a section of peyote from the gourd and, after touching it to the pilgrim's forehead (in lieu of the fontanelle hidden under the hat or scarf), eyes, larynx, and heart, placed it into his or her mouth. The pilgrim was told to "chew it well, chew it well, for thus you will see your life." Then he summoned the non-Huichol observers and repeated the same ritual for them (as he had also included them in the knotting-in ceremony).

In the meantime Ramon had gathered up all the tobacco gourds (yaw&e) belonging to the pilgrims and placed them near the sacred cavities from which the peyote had been taken. As Lumholtz (1900:190) noted, these gourds are an indispensable part of the outfit of the hikuri seeker, giving him, as it were, priestly status (the tobacco gourd was also a priestly insignia in Aztec times). I have heard it said that )4, tobacco, was once a hawk and the ki4 , gourd, a snake. The tobacco is always the so-called wild species, Nicotiani rusticathe "tobacco of Tatewarl—which contains nicotine in far greater amounts than some domestic brands. Tobacco gourds are specially raised for the purpose. Those with numerous natural excrescences are highly valued, although smooth ones are also employed, sometimes with a covering of skin from the scrotum of a deer. This, of course, makes them especially powerful.

All the hikuri that had "grown from the horns and body of Elder Brother" had been dug up and set on the ground. Bows and arrows were stacked against a nearby cactus. Votive offerings and prayers addressed to the Deer and the Kakauyarixi were placed in a pile in front of the holes where the peyote had been. The pilgrims were seated on the ground in a circle. Ramon touched the offerings with his muvii.ri , prayed, and set fire to one of the little wool yarn paintings he had made, depicting Elder Brother. As the wax melted, the flames licked at the ceremonial arrows, and soon the entire pile of offerings and the dry creosote bush itself were ablaze. Ramon muttered incantations and with his nzuvibl wafted some of the smoke toward the sacred mountains. Then he rose and with a gourd filled with peyote passed in a ceremonial circuit from right to left on the inside of the circle to give each his portion of "Elder Brother's flesh." Forehead, eyes, larynx, and heart were touched and the peyote placed into the mouth of each pilgrim in turn. The matewamete especially were exhorted over and over to "chew it well, brother [or sister], so that you will see your life, so that it will appear to you with clarity." When Ramon came to ten-year-old Francisco, all turned to watch. Peyote is not given in any quantity to young children, but after the age of three it can be a sign whether or not the child has the disposition to become a mara' akemte . If he or she likes the taste, which is exceedingly bitter and difficult to tolerate, it is taken as a positive omen. If it is rejected, it is a negative sign—though not necessarily definitive. RamOn touched Francisco on the head, eyes, throat, . and heart and placed a small piece between his lips. "Chew, little brother," he admonished, "and we will see how you like it. Chew well, chew well, for it is sweet, it is delicious to the taste." There were smiles at this obvious reversal but no laughter—this was not a time for hilarity. After slight hesitation Francisco, who had not tasted peyote before, began to chew vigorously. He nodded—yes, he liked it. Later he participated with great enthusiasm in the search for peyote and that night ate a goodly amount himself, with no visible ill effect. He danced for hours, fell asleep smiling happily, and next morning was his old self. One matewáme who was obviously greatly moved by the whole experience was Veradera, a strikingly handsome young woman apparently under twenty. Veradera ate more peyote than anyone with the exception of Ramon and Lupe, and later that night fell into a deep trance that lasted for many hours and caused everyone to regard her as especially sacred.

"You Will See Your Life"

When every one of the companions had chewed a piece of the first sacrificial hikuri, Ramon took out his fiddle and one of the others a guitar (both homemade), and the veterans stood aside in a group to sing and dance the matew6mete into a -receptive condition." In the meantime, another gourd had been filled with peyote cut into small pieces, and the initiates were not allowed to rise until they had emptied it. As the bowl was handed around, the others, led by Ramon, exhorted them over and over to "chew well, companion, chew well, for that is how you will see your life." Lupe then took a

sizable whole plant, sliced off the bottom, lifted her long, magnificently embroidered skirt (like Ramón's clothes, it had been made specially for this journey), and rubbed the moist end of the cactus on her legs, especially on the numerous small scratches and cuts inflicted by spines and thorns during the trek through the desert. The others followed her example. Lupe explained that peyote not only discourages hunger and thirst and restores one's spirit but heals wounds and prevents infection.

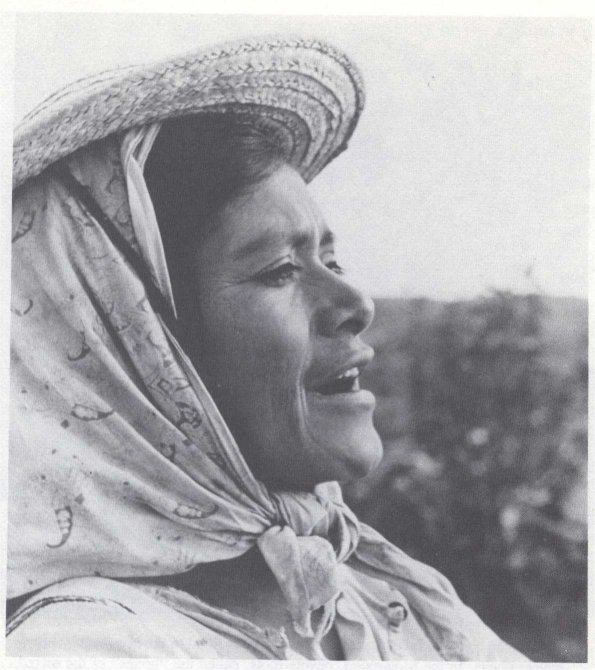

Veradera. "We are all the children of a brilliantly colored flower, a flaming flower. . . ."

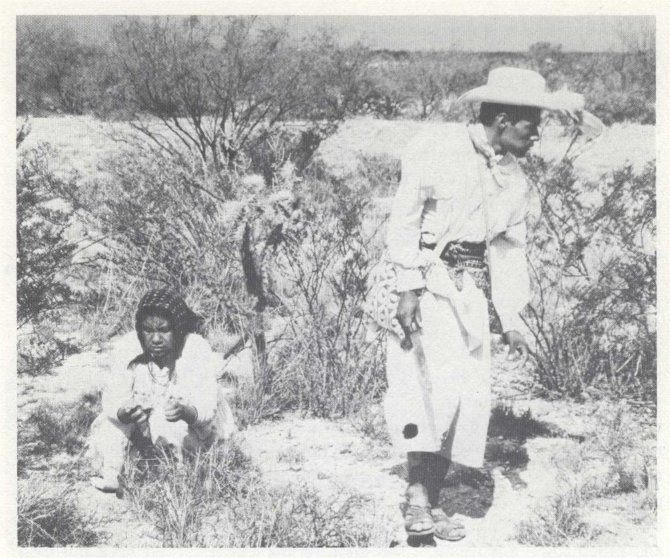

Ramon having admonished the companions repeatedly to "be of a pure heart," the actual hikuri harvest was ready to commence, and the pilgrims went off into the desert, alone or in pairs. Hikuri "hides itself well," and several of the companions had to walk a considerable distance before seeing their first peyote. Lupe, on the other hand, almost at once discovered a thicket of cactus and mesquite so rich in peyote that in a couple of hours she had filled her tall collecting basket. Occasionally she would stop to admire and speak quietly to an especially beautiful hikuri and to touch it to her forehead, face, throat, and heart before adding it to the others. We also saw people exchanging gifts of peyote. This seemed to us a very beautiful aspect of the pilgrimage. No ceremony in which peyote was eaten communally went by without this kind of ritual exchange, in which each participant is expected to share his peyote with every companion. A man or a woman would carefully divide a peyote, rise, and walk from individual to individual, handing over a piece and receiving one in return. Often an older participant would place his gift directly into the mouth of a younger one, urging him to "chew well, younger brother, chew well, so that you will see your life." But most often these ritual exchanges took place in silence as they were also to do in the concluding ceremony of "unknotting" that marked the formal end of the pilgrimage.

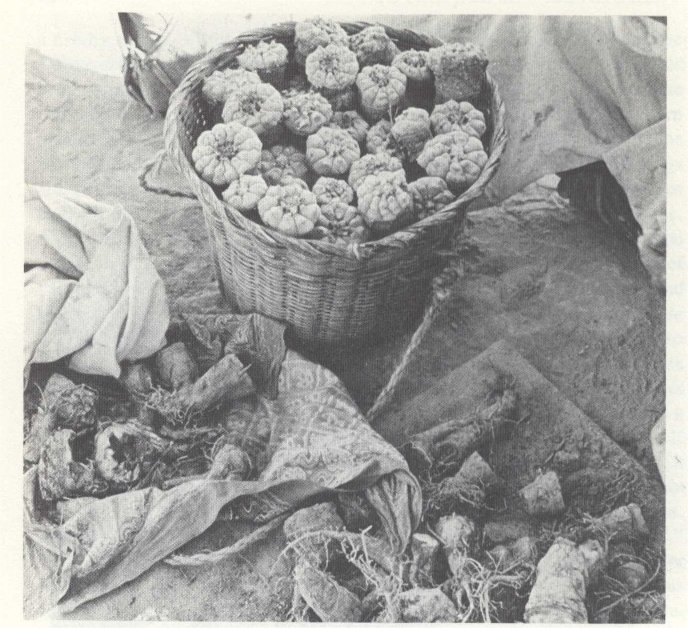

"Our game bags are full." Lupe's carrying basket filled to the brim with mature peyote plants. In the foreground, peyote roots, called the "bones" of the sacred cactus, cut off to be ritually deposited in the desert in the hope that new plants will grow from them. This accords with the widespread belief of hunting peoples in rebirth from the bones, which are believed to contain the life force or soul.

No hikuri was ever dug carelessly or dropped casually on the ground or into a basket or bag. On the contrary, it was handled with tenderness and respect and addressed soothingly by the hikuri seeker, who would thank it for allowing itself to be seen, call it by endearing names, and apologize for removing it from its home. As mentioned, small, tender, five-ribbed ("five-pointed") plants are considered especially desirable. Being young, they are also less disagreeable to the taste. Some plants were cleaned and popped directly into the mouth—after first being held to forehead, face, and heart. Lupe sometimes wept when she did this. She was also chewing incessantly, as was Ramon.

Toward four in the afternoon RamOn rose from where he had been digging peyotes and called out that it was time to return to camp. One of the hikuri seekers had just spotted a sizable cluster and was reluctant to abandon so rich a find. Ramon admonished him: "Our game bags are full. One must not take more than one needs." If one did, if one did not leave gifts and propitiate the slain Deer-Peyote (just as one should propitiate the spirits of animals one hunts, the maize one harvests, and the trees one cuts). Elder Brother would be offended and would conceal the hikuri or withdraw them altogether, so that next time the seekers would walk away empty-handed. We would call this practice conservation; to the Huichol it is part of the principle of reciprocity by which he orders his social relationships and his relationship to the natural and supernatural environment. So the pilgrims gathered their gear and their bags and baskets, now heavy with peyote, and after a tearful farewell returned to camp as they had come, walking single file to the sound of the bow. On the way they stopped here and there to pick up "food" for Tatewari.

On arriving at camp they made the usual ceremonial circuit around the fire and offered thanks for its protection, without laying down their burdens. Again there was much weeping. RamOn's basket, held in one arm while he gestured in the sacred directions with the other, must have weighed a good thirty pounds. Though dormant, the ashes were still aglow, and new flames quickly licked through the growing pile of brush as each deposited some "food" for Tatewarl. The green branches, wet with dew, sent thick clouds of white smoke billowing to the leaden sky. It was turning cold and damp.

Hikuri seekers. A Huichol peyotero and his wife searching the desert for the sacred cactus.

The night was passed in singing and dancing around the ceremonial fire, chewing peyote in astounding quantities, and listening to the ancient stories. Considering the lack of food, the long days on the road, the bitterly cold nights with little sleep (by now, Ramon had not closed his eyes to sleep for six days and nights!), and above all the high emotional pitch of the sacred drama, with its succession of increasingly intense and exalted encounters, one might have expected the pilgrims to feel some letdown now that they had successfully "hunted the deer" and to lapse into a dream state induced by the considerable quantities of hikuri they had already consumed. True, after their return from the hunt they were, for the most part, somewhat subdued and quiet. Some had actually entered trances. Veradera had been sitting motionless for hours, arms clasped around her knees, eyes closed. When night fell Lupe placed candles around her to protect her against attacks by sorcerers while her soul was traveling outside her body. But most of the others were wide awake, in varying states of exaltation, supremely happy and possessed of seemingly boundless energy. If the dancing and singing stopped it was only because Ramon laid down his fiddle to commune quietly with the ceremonial fire or to chant the stories of the first peyote pilgrims and the primordial hunt of the divine Deer-Peyote. It is also in this semi-conscious peyote dream state that the mara'alcame "obtains" the new peyote names for the pilgrims in his charge (e.g. Offering of the Blue Maize, Votive Gourd of the Sun, Arrows of Tatewari). These names, I was told, emerge from the core of the fire in the manner of brilliantly colored, luminous ribbons, and it is in this form that Ramon subsequently depicted them in his superbly fashioned "paintings" of wool yarn, an art form for which the Huichols are justly famed and in which he in particular excelled far beyond most other Huichol artists of his time. The special peyote names are conferred on the hikuri-seekers on the last day in Wiriluita and are evidently preserved by them at least until they are formally released from their sacred bonds and restrictions by the ceremonial circuit to the sacred places and the deer hunt that follow their return to the Sierra.

Uniqueness of the Shaman's Visions

The Huichols say their peyote experiences are very private things and they do not often discuss them with outsiders except in the most general terms ("there were many beautiful colors," "I saw maize in brilliant hues, much maize," or simply, "I saw my life"). Under certain conditions the mara'akitme might be called upon to assist in giving form and meaning to a vision, especially for one who is a matewitme (novice) or in the context of a cure. This much is clear, however: beyond certain "universal" visual and auditory sensations, which may be laid to the chemistry of the plant and its effect on the central nervous system, there are powerful cultural factors at work that here as elsewhere influence, if they do not actually determine, both content and interpretation of the drug experience. Huichols told me they were convinced that the mara'akme , or one preparing himself to become a mara'akitme, and the ordinary person have different kinds of peyote experiences. Certainly a mara'akáme embarks on the pilgrimage and the drug experience itself with a somewhat different set of expectations than the ordinary Huichol. He seeks to experience a catharsis that allows him to enter upon a ptisonal encounter with Tatewari and travel to "the fifth level" to meet the supreme spirits at the ends of the world. And so he does. Ordinary Huichols also "experience" the supernaturals, but they do so essentially through the medium of their shaman. In any event, I have met no one who was not convinced of this essential difference or who laid claim to the same kinds of exalted and illuminating confrontations with the Otherworld as the mara'akame . In an objective sense his visions might be similar, but subjectively they are differently perceived and interpreted. Certainly this applies to the mara'akame or aspiring mara'akitme who leads the peyoteros as the personification of Tatewari, the First Mara'akitme, and who is so addressed by his companions for the duration of the pilgrimage.

However, a rather surprising number of Huichol adult men, and some women too, consider themselves, and are considered by their fellows, to be shamans, so that the more intense peyote experience attributed to shamans can be assumed to be relatively widely shared. The pervasiveness of shamanism among the Huichols was first noted by Lumholtz in the 1890's (Lumholtz, 1900). His estimate of perhaps half the adult males as shamans seemed to me at first improbably high for an agricultural people like the Huichols, however incipient and primitive their agricultural economy may be in cornparison to that of other peoples with a longer tradition of farming and a more advanced agricultural technology. But Lumholtz turned out to be right, at least in the sense that all household heads really are family shamans, some with considerable prestige that extends far beyond their immediate kinfolk, and that at least half the men, and some women, possess a good deal of shamanic and ritual knowledge and presumably have had profound ecstatic trance experiences with peyote. Some shamans, of course, are considered to have much greater mystical powers than others, and their counsel carries correspondingly greater weight.

The Children of Peyote

The hikuri seekers left as they had entered—on foot, single file, blowing their horns. Their once-white clothing was caked with the yellow earth of the desert, for during the night it had begun to drizzle—an astonishing event at the height of the dry season and an auspicious omen. Behind them a thin plume of blue smoke rose from the ceremonial fire. They had circled it as required. They had made their offerings of tobacco and bits of food and sacred water from the springs of Our Mothers. They had purified their sandals. They had wept bitter tears as they bade farewell to Tatewari, to Elder Brother, to the Kakauyarixi . They had found their life. They had confirmed the sacred truths with their own senses, the inner vision that comes only when one eats the flesh of the divine Deer-Peyote. Now they were truly Vixorika (Huichol).

A few hundred yards down the trail they halted once more. Facing the mountains and the sun, they shouted their pleasure at having found their life, and their pain at having to depart so soon. "Do not leave," they implored the supematurals, "do not abandon your places, for we will come again another year." And they sang, song after song—their parting gift to the Kakauyarixi:

What pretty hills, what pretty hills,

So very green where we are.

Now I don't even feel, Now I don't even feel,

Now I don't even feel like going to my rancho.

For there at my rancho it is so ugly,

So terribly ugly there at my rancho,

And here in Wirikilta so green, so green.

And eating in comfort as one likes,

Amid the flowers (peyote), so pretty.

Nothing but flowers here,

Pretty flowers, with brilliant colors,

So pretty, so pretty.

And eating one's fill of everything,

Everyone so full here, so full with food.

The hills very pretty for walking,

For shouting and laughing,

So comfortable, as one desires,

And being together with all one's companions.

Do not weep, brothers, do not weep.

For we came to enjoy it,

We came on this trek,

To find our life.

For we are all,

We are all,

We are all the children of,

We are all the sons of

A brilliantly colored flower,

A flaming flower.

And there is no one,

There is no one,

Who regrets what we are.

*The description of the peyote pilgrimage in Chapters Ten and Eleven appeared earlier in somewhat different form in Flesh of the Gods: The Ritual Use of Hallucinogens, Peter T. Furst, ed. (C) 1972 by Praeger Publishers, Inc.), and in a briefer version in 1973 in Natural History, Vol. LXXXII, No. 4, pp. 34-43, and is included here with the permission of the publishers.

*Anderson (1969), who has been engaged in extensive field studies of Lophophora throughout its natural range from Texas to San Luis Potosi and Queretaro since 1957, reports that "injury or harvesting by man induces the formation of many stems from a single rootstock. Single clones of more than 1.5 m. across have been observed in San Luis Potosi, for example" (p. 302). The ritual practice of leaving part of the rootstock in the ground to induce new growth "from Elder Brother's bones" is common among Huichol peyote seekers. Clones growing from a single rootstock are considered especially sacred and powerful and are treated accordingly. Ramon, for example, would not allow anyone else to touch one such clone he had removed from the ground until it had been propitiated in the proper manner. Characteristically, he left part of the root where it grew.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|