The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia

The Mafia Restored: Fighters for Democracy in World War II

World War II gave the Mafia a new lease on life. In the United States, the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) became increasingly concerned over a series of sabotage incidents on the New York waterfront, which culminated with the burning of the French liner Normandie on the eve of its christening as an Allied troop ship.

Powerless to infiltrate the waterfront itself, the ONI very practically decided to fight fire with fire, and contacted Joseph Lanza, Mafia boss of the East Side docks, who agreed to organize effective antisabotage surveillance throughout his waterfront territory. When ONT decided to expand "Operation Underworld" to the West Side docks in 1943 they discovered they would have to deal with the man who controlled them: Lucky Luciano, unhappily languishing in the harsh Dannemora prison. After he promised full cooperation to naval intelligence officers, Luciano was rewarded by being transferred to a less austere state penitentiary near Albany, where he was regularly visited by military officers and underworld leaders such as Meyer Lansky (who had emerged as Luciano's chief assistant). (14)

While ONI enabled Luciano to resume active leadership of American organized crime, the Allied invasion of Italy returned the Sicilian Mafia to power.

On the night of July 9, 1943, 160,000 Allied troops landed on the extreme southwestern shore of Sicily.(15) After securing a beachhead, Gen. George Patton's U.S. Seventh Army launched an offensive into the island's western hills, Italy's Mafialand, and headed for the city of Palermo. (16) Although there were over sixty thousand Italian troops and a hundred miles of boobytrapped roads between Patton and Palermo, his troops covered the distance in a remarkable four days.(17)

The Defense Department has never offered any explanation for the remarkable lack of resistance in Patton's race through western Sicily and pointedly refused to provide any information to Sen. Estes Kefauver's Organized Crime Subcommittee in 1951.(18) However, Italian experts on the Sicilian Mafia have never been so reticent.

Five days after the Allies landed in Sicily an American fighter plane flew over the village of Villalba, about forty-five miles north of General Patton's beachhead on the road to Palermo, and jettisoned a canvas sack addressed to "Zu Calo." "Zu Calo," better known as Don Calogero Vizzini, was the unchallenged leader of the Sicilian Mafia and lord of the mountain region through which the American army would be passing. The sack contained a yellow silk scarf emblazoned with a large black L. The L, of course, stood for Lucky Luciano, and silk scarves were a common form of identification used by mafiosi traveling from Sicily to America. (19)

It was hardly surprising that Lucky Luciano should be communicating with Don Calogero under such circumstances; Luciano had been born less than fifteen miles from Villalba in Lercara Fridi, where his mafiosi relatives still worked for Don Calogero. (20) Two days later, three American tanks rolled into Villalba after driving thirty miles through enemy territory. Don Calogero climbed aboard and spent the next six days traveling through western Sicily organizing support for the advancing American troops. (21) As General Patton's Third Division moved onward into Don Calogero's mountain domain, the signs of its dependence on Mafia support were obvious to the local population. The Mafia protected the roads from snipers, arranged enthusiastic welcomes for the advancing troops, and provided guides through the confusing mountain terrain. (22)

While the role of the Mafia is little more than a historical footnote to the Allied conquest of Sicily, its cooperation with the American military occupation (AMGOT) was extremely important. Although there is room for speculation about Luciano's precise role in the invasion, there can be little doubt about the relationship between the Mafia and the American military occupation.

This alliance developed when, in the summer of 1943, the Allied occupation's primary concern was to release as many of their troops as possible from garrison duties on the island so they could be used in the offensive through southern Italy. Practicality was the order of the day, and in October the Pentagon advised occupation officers "that the carabinieri and Italian Army will be found satisfactory for local security purposes. (23) But the Fascist army had long since deserted, and Don Calogero's Mafia seemed far more reliable at guaranteeing public order than Mussolini's powerless carabinieri. So, in July the Civil Affairs Control Office of the U.S. army appointed Don Calogero mayor of Villalba. In addition, ANIGOT appointed loyal mafiosi as mayors in many of the towns and villages in western Sicily. (24)

As Allied forces crawled north through the Italian mainland, American intelligence officers became increasingly upset about the leftward drift of Italian politics. Between late 1943 and mid 1944, the Italian Communist party's membership had doubled, and in the German-occupied northern half of the country an extremely radical resistance movement was gathering strength; in the winter of 1944, over 500,000 Turin workers shut the factories for eight days despite brutal Gestapo repression, and the Italian underground grew to almost 150,000 armed men. Rather than being heartened by the underground's growing strength, the U.S. army became increasingly concerned about its radical politics and began to cut back its arms drops to the resistance in mid 1944. (25) "More than twenty years ago," Allied military commanders reported in 1944, "a similar situation provoked the March on Rome and gave birth to Fascism. We must make up our minds-and that quickly-whether we want this second march developing into another 'ism.' (26)

In Sicily the decision had already been made. To combat expected Communist gains, occupation authorities used Mafia officials in the AMGOT administration. Since any changes in the island's feudal social structure would cost the Mafia money and power, the "honored society" was a natural anti-Communist ally. So confident was Don Calogero of his importance to AMGOT that he killed Villalba's overly inquisitive police chief to free himself of all restraints. (27) In Naples, one of Luciano's lieutenants, Vito Genovese, was appointed to a position of interpreterliaison officer in American army headquarters and quickly became one of AMGOT's most trusted employees. It was a remarkable turnabout; less than a year before, Genovese had arranged the murder of Carlo Tresca, editor of an anti-Fascist Italian-language newspaper in New York, to please the Mussolini government. (28)

Images: Carlo Tresca (left). Carlo Tresa dead on the street (Archives of Labor Urban Affairs, Wayne State University) (center). Carmine Galante (UPI Bettman) (rigth) Carlo Tresca (1879-1943), was born in Italy in 1879. After being active in the Italian Railroad Workers' Federation, Tresca moved to the United States in 1904. Elected secretary of the Italian Socialist Federation of North America and a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), he took part in strikes of Pennsylvania coal miners before becoming involved in the important industrial disputes in Lawrence and Paterson. Tresca, who lived with Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, was editor of the anti-fascist newspaper, Il Martello (The Hammer) for over 20 years. Carlo Tresco was leader of the Anti-Fascist Alliance and was assassinated in New York City in 1943. Many of Tresca's comrades believed that his murder had been ordered by Generoso Pope, the ex-fascist publisher of Il Progresso Italo-Americano, as Tresca had attacked him relentlessly throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. One plausible theory said that Tresca was killed at the order of an Italian underworld figure named Frank Garofalo, identified as a member of the Mafia. Another theory said that Carmine Galante was the man who undoubtedly killed him. Galante was to become one of the most significant figures in a criminal group that has operated in New York, and beyond, for seventy years. On that dark, miserable January night when he gunned down his target, the probable killer Galante was already associated with or indeed possibly a member of a Mafia organization that is known today as the Bonanno Crime Family. ()

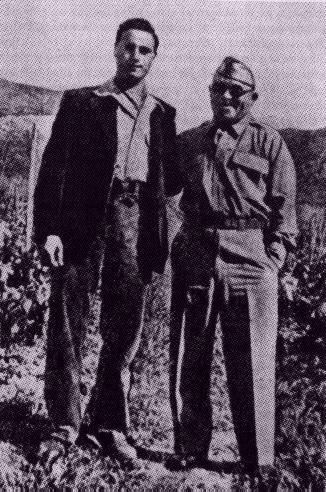

Image: Vito Genovese (rigth) with Salvatore Giuliano (left). Genovese was Colonel Poletti's driver, interpreter and consiglieri (adviser).

Genovese and Don Calogero were old friends, and they used their official positions to establish one of the largest black market operations in all of southern Italy. Don Calogero sent enormous truck caravans loaded with all the basic food commodities necessary for the Italian diet rolling northward to hungry Naples, where their cargoes were distributed by Genovese's organization (29) All of the trucks were issued passes and export papers by the AMGOT administration in Naples and Sicily, and some corrupt American army officers even made contributions of gasoline and trucks to the operation.

In exchange for these favors, Don Calogero became one of the major supporters of the Sicilian Independence Movement, which was enjoying the covert support of the OSS. As Italy veered to the left in 1943-1944, the American military became alarmed about their future position in Italy and felt that the island's naval bases and strategic location in the Mediterranean might provide a possible future counterbalance to a Communist mainland. (30) Don Calogero supported this separatist movement by recruiting most of western Sicily's mountain bandits for its volunteer army, but quietly abandoned it shortly after the OSS dropped it in 1945.

Don Calogero rendered other services to the anti-Communist effort by breaking up leftist political rallies. On September 16, 1944, for example, the Communist leader Girolama Li Causi held a rally in Villalba that ended abruptly in a hail of gunfire as Don Calogero's men fired into the crowd and wounded nineteen spectators. (31) Michele Pantaleone, who observed the Mafia's revival in his native village of Villalba, described the consequences of AMGOT's occupation policies:

By the beginning of the

Second World War, the Mafia was restricted to a few isolated and scattered

groups and could have been completely wiped out if the social problems of the

island had been dealt with . . . the Allied occupation and the subsequent slow

restoration of democracy reinstated the Mafia with its full powers, put it once

more on the way to becoming a political force, and returned to the Onorata

Societa the weapons which Fascism had snatched from it.

(32)