The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia

The Mafia in America

At first the American Mafia ignored this new business opportunity. Steeped in the traditions of the Sicilian "honored society," which absolutely forbade involvement in either narcotics or prostitution, the Mafia left the heroin business to the powerful Jewish gangsters-such as "Legs" Diamond, "Dutch" Schultz, and Meyer Lansky-who dominated organized crime in the 1920s. The Mafia contented itself with the substantial profits to be gained from controlling the bootleg liquor industry.(8)However, in 1930-1931, only seven years after heroin was legally banned, a war erupted in the Mafia ranks. Out of the violence that left more than sixty gangsters dead came a new generation of leaders with little respect for the traditional code of honor."

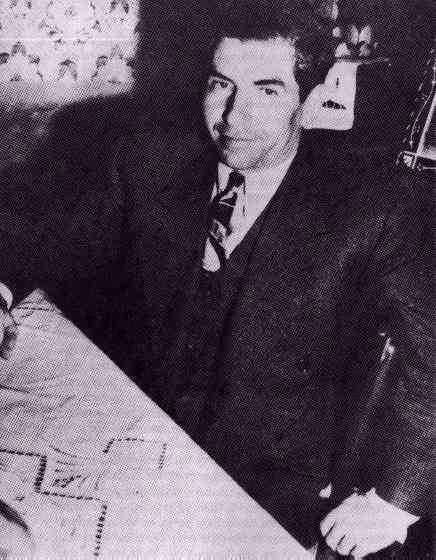

Image: Salvatore Lucania, alias Lucky Luciano.

The leader of this mafioso youth movement was the legendary Salvatore C. Luciana, known to the world as Charles "Lucky" Luciano. Charming and strikingly handsome, Luciano must rank as one of the most brilliant criminal executives of the modern age. For, at a series of meetings shortly following the last of the bloodbaths that completely eliminated the old guard, Luciano outlined his plans for a modern, nationwide crime cartel. His modernization scheme quickly won total support from the leaders of America's twenty-four Mafia "families," and within a few months the National Commission was functioning smoothly. This was an event of historic proportions: almost singlehandedly, Luciano built the Mafia into the most powerful criminal syndicate in the United States and pioneered organizational techniques that are still the basis of organized crime today. Luciano also forged an alliance between the Mafia and Meyer Lansky's Jewish gangs that has survived for almost 40 years and even today is the dominant characteristic of organized crime in the United States.

With the end of Prohibition in sight, Luciano made the decision to take the Mafia into the lucrative prostitution and heroin rackets. This decision was determined more by financial considerations than anything else. The predominance of the Mafia over its Jewish and Irish rivals had been built on its success in illegal distilling and rumrunning. Its continued preeminence, which Luciano hoped to maintain through superior organization, could only be sustained by developing new sources of income.

Heroin was an attractive substitute because its relatively recent prohibition had left a large market that could be exploited and expanded easily. Although heroin addicts in no way compared with drinkers in numbers, heroin profits could be just as substantial: heroin's light weight made it less expensive to smuggle than liquor, and its relatively limited number of sources made it more easy to monopolize.

Heroin, moreover, complemented Luciano's other new business venture-the organization of prostitution on an unprecedented scale. Luciano forced many small-time pimps out of business as he found that addicting his prostitute labor force to heroin kept them quiescent, steady workers, with a habit to support and only one way to gain enough money to support it. This combination of organized prostitution and drug addiction, which later became so commonplace, was Luciano's trademark in the 1930s. By 1935 he controlled 200 New York City brothels with twelve hundred prostitutes, providing him with an estimated income of more than $10 million a year. (9) Supplemented by growing profits from gambling and the labor movement (gangsters seemed to find a good deal of work as strikebreakers during the depression years of the 1930s) as well, organized crime was once again on a secure financial footing.But in the late 1930s the American Mafia fell on hard times. Federal and state investigators launched a major crackdown on organized crime that produced one spectacular narcotics conviction and forced a number of powerful mafiosi to flee the country. In 1936 Thomas Dewey's organized crime investigators indicted Luciano himself on sixty-two counts of forced prostitution. Although the Federal Bureau of Narcotics had gathered enough evidence on Luciano's involvement in the drug traffic to indict him on a narcotics charge, both the bureau and Dewey's investigators felt that the forced prostitution charge would be more likely to offend public sensibilities and secure a conviction. They were right. While Luciano's modernization of the profession had resulted in greater profits, he had lost control over his employees, and three of his prostitutes testified against him. The New York courts awarded him a thirtyto fifty-year jail term. (10)

Luciano's arrest and conviction was a major setback for organized crime: it removed the underworld's most influential mediator from active leadership and probably represented a severe psychological shock for lower-ranking gangsters.

However, the Mafia suffered even more severe shocks on the mother island of Sicily. Although Dewey's reputation as a "racket-busting" district attorney was rewarded by a governorship and later by a presidential nomination, his efforts seem feeble indeed compared to Mussolini's personal vendetta against the Sicilian Mafia. During a state visit to a small town in western Sicily in 1924, the Italian dictator offended a local Mafia boss by treating him with the same condescension he usually reserved for minor municipal officials. The mafioso made the foolish mistake of retaliating by emptying the piazza of everyone but twenty beggars during Mussolini's speech to the "assembled populace."(11) Upon his return to Rome, the outraged Mussolini appeared before the Fascist parliament and declared total war on the Mafia. Cesare Mori was appointed prefect of Palermo and for two years conducted a reign of terror in western Sicily that surpassed even the Holy Inquisition. Combining traditional torture with the most modern innovations, Mori secured confessions and long prison sentences for thousands of mafiosi and succeeded in reducing the venerable society to its weakest state in a hundred years."(12) Although the campaign ended officially in 1927 as Mori accepted the accolades of the Fascist parliament, local Fascist officials continued to harass the Mafia. By the beginning of World War II, the Mafia had been driven out of the cities and was surviving only in the mountain areas of western Sicily.(13)