HISTORICAL INTERPRETATIONS

| Books - The Peyote Cult |

Drug Abuse

HISTORICAL INTERPRETATIONS

THE PRE-PEYOTE MESCAL BEAN CULT

As we have noted in the section on the botany of peyote, the use of the term "mescal" is surrounded with considerable confusion, and is persistently used in the older literature to designate Lophophora williamsii or peyote. The true mescal is the Agave spp. whose cabbage-like center is baked by the tribes of the Southwest and northern Mexico as a food ; 'mescal" also refers to the brandy distilled from mescal beer or pulque. No doubt it is due to their intoxicating properties that two other distinct plants, Sophora secundifiora and Lophophora wilLiamsii, have been called, respectively, "mescal bean" and "mescal button." A further confusion of these last has been contributed to by the fact that both have been involved in Plains cult uses.

Sophophora secundiflora is an evergreen shrub bearing two or three tough-shelled red seeds in a bean-like pod. Known in Mexico as "toleselo" and elsewhere as mescal-bean, coral-bean,' frijolito, frijolillo and mountain laurel,' it contains the extremely toxic narcotic alka-loid sophorine or cytisine,' the physiological action of which accounts for its ceremonial use by natives. This is a powerful poison causing nausea, convulsions and finally death by asphyxiation; it is said4 to resemble nicotine closely in physiological action. A more complete botanical and physiological account appears in an appendix, and we are here con-cerned only with its ethnographic aspects.

Havard says that the Indians near San Antonio

formerly used the seed as an intoxicant, half of a seed producing a delirious exhilaration followed by a deep sleep lasting two or three days.

Opler tells a Chiricahua Apache coyote story in which the trickster pounded up a number of the beans and gave them to the people to eat:

So while the people were out of their minds, Coyote cut out their hair in patches the way Indians cut their hair. So there they were, crazy.

Lumholtz says that the Tarahumari added the root (?) of the frijolillo to their maguey wine "as a ferment," and Bennett and Zingg report an archaeological occurrence at a Rio Fuerte site in Chihuahua on a Basket-Maker horizon:

Containers found here and in another site held nothing but a few seeds of the poisonous wild "bean," which may have ceremonial significance.

This inference is not implausible when we recall the Mexican mode of keeping peyote.'

The use of peyote in racing and in ball games is noted for the Tarahumari and Tamauli-pecan groups, and in this connection it is interesting to learn that the Wichita used to eat mescal beans before they ran a race. A Cheyenne informant said that his tribe used the "red-berry" as an eye-wash long before they knew of peyote, though he never heard of their eating it; "it's poison," he said. The Comanche used to get mescal beans from near Fort Stanton, apparently for ornamental purposes only.' Like most of the Plains tribes, the Kickapoo used mescal beans chiefly as beads, but in common with the Cheyenne they used them medicinally: for earache they boiled, mashed and strained the beans through a cloth.

The Kiowa use the IbrikoX or mescal beans typically, as beads in peyote meetings, much as they formerly wore bandoliers of them on the warpath. One Kiowa is said to have chewed the inside of a mescal bean before breaking a bad wild horse bareback. A Kiowa peyote chief had several of the beans on his moccasin heel-fringe, to protect from the dangers of inadvertently stepping on menstrual blood, and another Kiowa "peyote boy" had a mescal bean attached to the thong of his gourd rattle. Mescal beans are clearly thought to possess great medicine-power.

The Iowa had leggings which Skinner thought might have been of a modified Kiowa• Comanche type, with a perforated scarlet mescal bean (Iowa, maka shutze, "red medicine") knotted on each thong of the fringe. The Omaha used as beads and good luck charms bright red beans which Gilmore thought were Erythrina, and which they called makan zhide or "red medicine" likewise. In adopting the use of chinaberries (Melia azerdache L.) as beads, they likened them to mescal beans and called them, curiously, makan-zhide sabe, "black red-medicine."' Pawnee informants said that long ago they used bat or mescal beans for medicine "to strengthen the body," but now use them only for decoration. The Oto used to eat "liar(?) berries" or mescal beans in one of their lodges; they had the inter, esting superstition that they breed (recalling the sex attributed to peyote) :

The two or three in a bundle, leave it a year or so, and when you open it again you'll have a dozen.

The inference that the Pawnee and Oto used the mescal bean ritually is borne out by the Iowa, who had a full-fledged ceremony called the "Red Bean Dance :"'

This is an ancient rite (maukácutzi waci) far antedating the modern peyote eating practice but on the same principle. The society was founded by a faster who dreamed that he received it from the deer, for red beans (mescal) are sometimes found in deer's stomachs, There are four assistant leaders, besides the leader, and it is their duty to strike the drum and sing during ceremonies.

In this society members were obliged to purchase admission from some one of the four assistant leaders. This was done in the regular ceremonial way. A candidate brought gifts and heaped them on the ground before the assistant leader and begged for the songs, etc., which he taught them and was then a leader. There was no initiation ceremony. During performances the members painted themselves white and wore a bunch of split owl-feathers on their heads. Small gourd rattles were used and the members while singing held a bow and arrow in the right hand which they waved back and forth in front of the body while they manipulated the rattle with the left.

This ceremony was held in the spring when the sunflowers were in blossom on the prairie, for then nearly all the vegetable foods given by wakanda were ripe. The leader, who was the owner of a medicine and war bundle called mankácutzi warfihawe connected with this society, had his men prepare by "killing" the beans" by placing them before the fire until they turned yellow. Then they are taken and pounded up fine" and made into a medicine brew. The members then danced all night, and just past midnight they commenced to drink the red bean decoction. They kept this up until about dawn when it began to work upon them so that they vomited" and prayed repeatedly, and were thus cleansed ceremonially, the evil having been driven from their bodies. Then a feast of the new vegetable foods" was given them and a prayer of thanks was made to wakanda for vegetable foods and tobacco.

The connection of the ma nkácutzi warfihawe, or red bean war bundle with the society is not altogether clear to me, save that it was a sacred object possessed by the society which brought success in war, hunting, especially for the buffalo, and in horse-racing." Members of this society tied red beans around their belts when they went to war, deeming them a protection against injury." Cedar berries and sagebrush were also used with this medicine." Sage was boiled and used to medicate sweat baths on the war trail .

Further information is afforded by Harrington," who collected a typical red bean bundle figured by Skinner, indicating a Pawnee parallel to the Iowa cult:

In addition to the two varieties of Ioway war bundles before described, a third sort was found, Mankanshudje oyu, or Red Medicine Bundles .... This was not discussed with the others, for the reason that the Ioways claim that it did not originate with them, but was derived from the Pawnee, who, in return for many presents, gave them authority to use it, and instructed them in its preparation and ritual. The legend of its origin among the Pawnee was not known to my informants.

The bundle, says Chief Tohee, belonged to a society, whose annual meeting was held about the time corn is ripe." There was but one main bundle, but each member had a "flute" or whistle, and a small package of medicine. When the time approached for the meeting, the member who was to give the feast sent a crier or "waiter" around to the different members, calling them to meet at a certain night in his bark house or tipi, whichever he was using at the time. All painted themselves and fixed themselves up in their best style for the occasion. Music was furnished by a number of singers, who kept time to the sound of drumming upon a tight bow-string," and the sound of small gourd rattles. During the ceremonies the singers seated themselves in four different places at the side of the lodge, corresponding to the four directions, and sang in each one the verses pre-scribed by tradition, the order being : east, south, west, and north.2° The dance is said to have con-sisted of peculiar jumping movements.

Now, the "Red Medicine" which forms the basis of the bundle, is the sacred red Mescal bean (Erythrina fiabelliformis) which seems to have narcotic or perhaps intoxicating properties when taken internally.21 Formerly widely used by the Indians of the Southern Plains22 to produce dreams or visions at certain ceremonies, it has now been supplanted by the more powerful "button" cut from the Peyote cactus, which is sometimes wrongly also called "mescal," thus taking the name of its predecessor.

When morning put an end to the dances of the ceremony under discussion, a large number of the red beans were broken up, or "killed" as the Indians say (regarding the beans as alive) and stirred up with water in a large kettle, together with certain herbs which are said to make the decoction milder in action. Then all the participants drank a cup or two of the mixture. The only description of the action of the drug was that everything looks red to the drinker for a while, when he vomits, and evacuates the bowels, which the Indians say, cleans out the system, and benefits the health, even in the case of children. The medicine drinking, and the stupor and purg-ing consequent upon it end the ceremony.

It is said that the bundle has been handed down for a number of generations, since it was obtained from the Pawnee, all in one family, which must have benefited considerably, one would think, from the valuable presents necessary to join the society . . . . The [bundle's] taboo was very strict, forbidding its owners to break the bones" of any animal under any circumstances. They must never allow the bundle to touch the ground either . . . .

When not in use, it was kept carefully wrapped in hides or canvas so as to exclude the weather, hanging on a pole standing just east of the owner's lodge, in front of the doorway. In addressing the bundle, they called it "Grandfather," and made offerings to it by throwing tobacco on the ground near the pole where it hung. On festal occasions the sweet smoke of burning cedar twigs was wafted upon it as an offering.

In time of war, a special man was appointed to carry it, as was the case with most war bundles.

Like them, too, it was opened when the enemy was sighted, when its enclosed amulets were put on by the warriors. Tooting their war-whistles, they rushed gaily into battle, confident of the Red Medicine's protection.

Mrs. Voegelinm quotes an informant on a Shawnee use of mescal in a war connection :

Calikwa's grandfather gave him one of these mescal beans (manitowimskaif Oa). This old man knew prayers about these beans . . He had four grandsons. He made a prayer to give each of these boys a bean—one apiece .... He made a prayer about how the Creator made these beans and how they're used, using tobacco . . . out in the woods; he built a fire, where he offered prayer. This old man wanted his grandsons to be warriors. So he told the first grandson to swallow one of those beans.

When the first boy swallowed the bean, the bean came out. He told the boy, "You can never be a powerful man or anything; there's something in the way, that that bean didn't want to stay (inside you)." This happened to three of the boys. The last grandson to take the bean was Calikwa; when he took it, the bean didn't come out. So when he saw his grandson keeping that bean, the old man was thankful. He told him, "Now you have a power; any time you see a battle you'll be the leader." [And so he was in 1865, when the Shawnee almost wiped out the Tonkawa in battle.]

HISTORY OF THE DIFFUSION OF PEYOTISM

Far too little is known—or probably ever will be known—about peyotism in Mexico to attempt to reconstruct its history; but our earliest Spanish sources indicate its pre-Columbian presence among the Aztec, and probably also the Cora-Huichol.25 But the latter do not live in the region of growth of the plant, whence Beals argues that they must cer-tainly have borrowed the cult. Rouhier claims immense antiquity for Huichol peyotism, but unconvincingly. If, indeed, as Beals with great plausibility argues, peyote is historically associated with shamanism, then it may have been involved in a late re-invigoration of shamanistic elements, at the expense of the priestly-saceradotal elements of an older, im-poverished culture stratum. Evidence is even less conclusive for other Mexican groups, but on the whole it appears that the ritualization of the use of peyote was already vigorous in many parts of Mexico at the time of the first Spanish contact.

The approximate age of the peyote cult among the Tarahumari is likewise unknown to us. It is not so integrated into their culture as in the case of the Huichol, and in nearly all respects the southern cult is more complex than the northern. Furthermore, Tarahumari peyotism has for some time been in decline, indicating perhaps a borrowing which was not sufficiently rooted—the neighboring Tubar, for example, did not use hikuli, though their customs otherwise much resembled the Tarahumari. Both Lumholtz and Bennett and Zingg consider Tarahumari peyotism a diffusion from the Coralluichol; certainly the Tarahumari themselves show very little indication of being a center of diffusion in Mexico in their lack of characteristic traits.26

Despite our comparative ignorance of the region, a much better case could be made for northeastern Mexico as a center of diffusion, for the region immediately south of the Rio Grande is one of the abundant growth of peyote. The oldest use in the United States is in this region, rather than in the Southwest as represented by the Mescalero. Tonkawan peyotism, for example, may be quite old: Velasco wrote in 1716 that many of the Indians of Texas drank "pellote" in connection with their dances. The Lipan got peyote from the Carrizo before white contact, according to Opler's informants. The Lipan used to go to a place called Bilsgulgai, which was "wide grass country beyond the Pecos in Texas," where the Mescalero came sometimes to meet them. Wagner says the Mescalero got peyote from the Lipan about 188o, but later Plains history of the cult as evidenced by the Kiowa leads us to accept the date 187o set by Opler, as more plausible. Opler has well accounted for the ready acceptance by the Mescalero of this shamanistically-colored complex, and its integration into their pattern of aggression by witchcraft; he believes that peyotism was brought to their door by the same movement which brought it to the Plains, though Mes-calero peyotism is appreciably older.27

From Dr. Parsons' careful account, it is clear that Taos practises the classical Plains rite. Contact with the Arapaho-Cheyenne version dates at least as far back as 1907, and tentative beginnings of this sort continued in later years.28 Interestingly, Cozio recorded in 172o the prosecution of a Taos Indian who had taken peyote and disturbed the town." In any case the history of peyote at Taos has been a stormy one." About 1918 the hierarchy became bitterly opposed to peyote, and turned three men out of their kiva membership in an attempt to rout it out. Dr. Parsons" believes that the weakness of the kachina cult at Taos accounts perhaps for peyote getting any foothold there at all. It is no coincidence that the Water Kiva, which has to do with the main elements of the kachina cult, the grimage, is the one most outstandingly opposed to peyote. Considerable political activity has erupted over the issue, and Dr. Parsons surmises that the protective influence of a recently deceased political figure in the pueblo was also of significance. It may well be that recent Federal legislation will so strengthen the hand of the civil authorities at Taos that the suppression of peyote can be accomplished; in 1923 the number of "peyote boys" was only 52 in a population of 635.

In the Plains the most important tribes in the diffusion of the peyote cult were the Kiowa, the Comanche, and to a lesser degree perhaps, the Caddo. Most Kiowa agree that they got peyote and the accompanying ritual from the Mescalero Apache. The usual story is that a raiding party came to the Apache country, and that during an Apache peyote meeting being held at the time, the leader by clairvoyant means was made aware of the approach of the war-party leader. He told his fireman to invite the man in, enemy though he was. In this manner the man learned the ceremony, and at the end he was presented with peyote and ritual paraphernalia to take back to his tribe.32

Pabo, or Big Horse, was the only user among the Kiowa about 1868 or 187o, and Mooney began to notice Kiowa peyote only around 1886, so the vigorous activity of a cult proper may be said to date from about this time (though friendly contacts with the Mescalero in his opinion dated as far back as 185o or before)." But the introduction of peyote was not exclusively the doing of one tribe, any more in the case of the Kiowa than of other groups. Tribal contacts have been multiple since the cessation of intertribal war-fare, and one is not at all inclined to discount the vague information from Kiowas that they knew of peyote from the Cáyeso, the Zé.bakieni or "Long Arrows," the Ywk'i (a loose designation for various north Mexican tribes) and the Kcon4co. These last so-called "bare-footed" people are probably the Carrizo, who ranged within the region of growth of peyote. The Tonkawa" also made visits to the Kiowa around 1890 and performed shaman, istic tricks in peyote meetings. We therefore set the date of Kiowa peyotism somewhat earlier than Shonle's" "before 1891" (her data were based on official Government sources which might not have become cognizant of the cult until late in its history), for Kiowa were holding meetings by 2880 or before. The Kiowa probably contributed little or nothing definitive to the general shape of the ceremony, most of whose features were already stand-ardized among the Lipan and the Mescalero."

At one time, however, there was intense opposition to peyote on the part of some Kiowa. In the winter of 1887-88 NigYä had a revelation on the strength of which he claimed to be the successor to Pate'te or "Buffalo-Bull-Coming-Out" (the "Buffalo Prophet" of 1881-82 who had promised to bring back the buffalo if his followers joined him in resisting the Whites and returning to the old customs). He organized a group of about thirty into an order called Baiyui or "Sons of the Sun," with a special costume, singing of guedwg31, or old "going-to-war" songs, smoking ceremony and dance. These he commanded to resume the old costume, weapons and customs, and distributed to them a sacred new fire made with a drill to take the place of fires kindled with flint-and-steel or matches. The Sons of the Sun were bitterly opposed to peyote on the ground that it was in conflict with the Ten Medi, cine Bundles, though since its introduction some years before there had been no special opposition to peyote. One of their rules was to drink always from an individual cup or bucket, in pointed contrast to the peyote custom.

B4igYä predicted that a great whirlwind would come in the spring, followed by a four-day prairie-fire in which the Whites and all their works would be destroyed and the buffalo and the old Indian life restored. He ordered all the Kiowa to gather at Elk Creek, where they would be safe when the catastrophe came. He claimed that his followers would be invulnerable to the white soldiers' bullets, and that he himself could kill the latter with the glance of his eye as far as he could see them. As the time grew near there was intense excit-ment and the whole tribe, save for a few skeptical chiefs and medicine men, assembled at the appointed spot. When the holocaust failed to materialize the people lost faith in him. He held his original group together until the coming of the Ghost Dance in the fall of 1899. Shortly before this his son had died, and when the Ghost Dance came he claimed to have seen the fresh tracks of this son on his grave, resurrected, and through this revelation at-tempted to identify his group with the Ghost Dance, without, however, any success. His disciples continued to ride around together in a group, and maintained their bitter hostility to peyote, but were not taken seriously. Finally, indeed, Lone Bear and other Sons of the Sun, became staunch peyote-users themselves and opposition vanished.

The first Comanche user of peyote was Buirat, who married an Apache woman and is said to have learned it from the Mescalero. Other early users were Degode ("Smart Man") and Tagipa, but by far the most important peyote leader among the Comanche was Quanah Parker. Previously opposed to it, he later changed his mind when peyote cured an illness of his. One of the earliest Comanche meetings was held east of Fort Sill in 1873 or 1874, about the time Kicking Bird was imprisoned there. Quanah subsequently visited the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ponca, Oto, Pawnee and Osage among others" and conducted meet, ings among them in the early 189o's. The Comanche origin legend is similar to that of the Kiowa, except that the White Mountain Apache were involved

Regardless of priority, the prestige of both these tribes as teachers of peyote is consid-erable." Due to their influence, peyote spread rapidly in Oklahoma until it assumed the proportions of an "international" religion such as the Ghost Dance had been. Distinctly a reservation phenomenon in the days following the cessation of inter-tribal warfare, peyot• ism was able to exploit the friendly contacts growing out of the Ghost Dance. As Opler writes, "The spread and increased prominence of peyote ceremonies coincided suggestively with the final triumph of white civilization over the tribes of our western plains, those very groups upon whom peyote obtained so strong a hold."

The express intention of Indian policy of the period was the deculturation of the na-tives, to be obtained by sending the children to white schools, away from the influence of tribal life." But this policy prepared the way for peyotism in several ways: it weakened the tradition of the older tribal religions without basically altering typical Plains religious attitudes, and multiplied friendly contacts between members of different tribes. Friend-ships made as school,boys account for considerable visiting and revisiting from tribe to tribe, and nearly ideal conditions for the diffusion of the cult were established. When Eagle Flying Above (Pawnee) got peyote from White Eyes (Arapaho) the sign language was the vehicle used, but in modern times the use of English as a lingua Franca is an enabling factor of great importance in the diffusion of the cult. Thus, ironically, the intended modes of deculturizing the Indian have contributed preëminently to the reinvig-oration of a basically aboriginal religion.

Among the groups of considerable secondary importance in this diffusion, the Caddo are perhaps outstanding. The variations which the Caddo-Delaware messiah John Wilson began, and taught to the Quapaw, Osage and other "Big Moon" worshippers, is a some, what special historical development and is treated in an appendix. The significance of the Oto in the development of the Christianized version among the Omaha, Winnebago and other Siouan groups is shown in another appendix on the history of the Church of the First-born and other peyote churches.

In the diffusion of the standard rite the Arapaho and the Cheyenne perhaps come next after the Kiowa and the Comanche. Jock Bullbear was one of the earliest Arapaho users, learning it from the Comanche when he returned from Carlisle° in 1884, and by 1891 Arapaho peyotism came to the attention of Mooney. A Cheyenne and Arapaho custom in connection with peyote meetings is the giving of presents to friends and visitors the next morning after a meeting." The sweat lodge doctoring modification of Arapaho peyotism has been described previously.

The Bannock of Idaho have used peyote since i906-1911, apparently against consider-able opposition. They formerly met in log-houses in the backwoods, and did not use the plant openly until the Oklahoma Native American Church was organized. The Cheyenne are believed by the writer to be the source of their cult.

The Blackfoot in 1913 were said to lack42 the peyote religion, but Wissler states that he heard them singing peyote songs within a hundred yards of the very agent who denied the existence of the cult among them. Alfred Wilson (Cheyenne), who as president of the Native American Church has occasion to know, says that the Blackfoot have peyote, though they were officially° listed as non-users in 1922.

The Five Civilized Tribes received peyote at a very late date. Wagner44 in 1932 said that the Creek, Choctaw and Chickasaw do not eat peyote; this agrees with the state-ments of Jim Aton (Kiowa) who said the Cherokee did not have it when he himself took peyote to the Creek in 1931. The Seminole have also taken it up recently, but some ac-quaintance with the plant must be postulated as early as 1922, since Newberne and Burke" list 4o users among the mi,5o6 population of the combined Five Tribes. The influence involved here is probably the Yuchi, who in turn got it from the Cheyenne."

The Cheyenne are currently a source for peyote among the Blood in Canada, who were being organized in the summer of 1936. The Canadian Cree and Chippewa are very recent partial converts too; the latter received it from the Chippewa of Minnesota.°

The Cheyenne in Oklahoma used peyote before 1885, the date of the first Government census. The Government scout Flacco was violently against it and said that it was used "to witch people and make them crazy." Cloud Chief, of the Snake Clan, also opposed the coming of peyote, as he had previously opposed the Ghost Dance. But Leonard Tylor and John Turtle went to the Kiowa country in 1884-85 and learned the ceremony. A little later, in 1889-90, Henry White Antelope and Standing Bird visited the Comanche and learned Quanah Parker's "way.'" Tylor later got a "heart moon" of his own (Caddo in-fluence?) some time after the allotment of lands.

Northern Cheyenne peyotism is largely parallel in its history to that of the Southern Cheyenne. It began among them around 'goo or before, some of them having learned it at Haskell; recently they have become affiliated with the Native American Church. Hoebel

writes :48

There has been a limited amount of friction between the religious conservatives and the Peyote worshippers, and a distinction is drawn between a Peyote leader and a medicine man For example, a ranking Peyote leader volunteered to give me much esoteric information on old cultural ways, explaining that he could talk to me about sacred things because he is not a medicine man. The Peyote people have taken over the entire leadership of tribal life. All members of the tribal council are Peyote worshippers and probably 8o per cent of the adults in the tribe are affiliated with the Peyote cult. Only the very old men abstained from Peyote and held to the old medicine beliefs. Among the Northern Cheyenne, Issiwin or theSacred Hat is still revered and is under the care of an old medi, cine man. The Peyote leaders took a sacred button to the hat keeper and asked him to put it in the ancient bundle with the old hat but they claim not to know whether the keeper had done so or not. My guess is that they did know but did not care to tell.

There is a tendency to separatism between the sections on the reservation, but nothing suggesting a schism in Northern Cheyenne peyotism; there is interparticipation in meetings of the various groups, though there is a mild rivalry between the Muddy Creek and the other territorially-defined groups.

The Delaware got peyote from the Kiowa and Comanche about 1886, the earliest users including Chief Charles Elkhair, Joe Washington, James C. Webber, George T. and John Anderson, Benjamin Hill, Reed and Frank Wilson, Mrs. Allie Anderson, Mrs. Ora Spy-buck and Mrs. Little Tethlies. Washington's family still has the original articles given them by the Comanche."

Iowa peyote° was in full swing in 1914, but is said to have died out since 1922. In this tribe the introduction of peyote

has driven out of existence almost all the other societies and ancient customs of the tribe; almost all of the Iowa in Oklahoma are ardent peyote disciples, and only . . . a few . . . still follow the older customs.

Peyotism has relaxed the rules of secrecy about the older medicine ceremonies also, and may perhaps be ultimately responsible for the final deculturation of the Iowa.

Kansa peyotism came from the Ponca about 1907. It was very strong among them by 1915, "having apparently superseded all of the old Kansa beliefs."

Henry Murdock (Kickapoo) brought the new religion from Quanah Parker and the Comanche in 1906; but he had personally known of peyote before, having gone to Mexico in 1864. Quanah had known Murdock before the peyote religion began spreading and in, vited his friend by letter to visit him. He put on a meeting in his honor, taught him the ceremony and presented him with peyote paraphernalia. The set songs in the Kickapoo rite are Comanche, and the custom of making the ashes into a bird likewise indicates a Comanche provenience for the ceremony. The Kickapoo were originally much against peyote."

Peyote began to have a limited adherence among the Menomini a little before 1914, owing largely to marital ties with Winnebago and Potawatomi users." The ritual has the Christian character of the Winnebagos' and membership in the peyote society not only precludes any in all the other societies, but also demands the abandonment of all ancient practices and destruction of their paraphernalia. Skinner believed that its success will mean the death-blow to all the ancient customs of the tribe, already decadent, with-out the compensation of any advantageous or progressive substitute.

The spread of the cult has been met with determined opposition among the Menomini, and some peyote users later sought and received reinstatement in the older tribal rites.

One Modoc in Oklahoma, Sam Ball, married a Quapaw woman and took up peyote as a result. At present he is the only one," but such marital ties have often before been the source of the spread of peyote.

Peyote was introduced to the Omaha"

in the winter of 1906—o7 by an Omaha returning from the Oto in Oklahoma. He had been much addicted to alcoholics, and was told by an Oto that the plant and the religious cult practiced there-with would be a cure. On his return he sought the advice and help of the leader of the Mescal Society of the Winnebago, next door neighbors tribe of the Omaha. He and a few other Omaha, who also suffered from alcoholism, formed a society which has since increased in numbers and influ-ence against much opposition, till it includes about half the tribe.

The medicine-men were particularly opposed to the use of peyote; one native Omaha, Thomas L. Sloan, prepared a bill against peyote and presented it to the Nebraska State Legislature, but later suffered a change of heart.

The Osage are a typical example of the multiple origins for peyotism in one tribe. Chief Lookout testified" that the Osage had peyote about 1896, and in a petition to Con-gress signed by him and Eves Tallchief, Edgar McCarthy and Arthur Bonnecastle, it was stated that Chief Black Dog and Chief Clermont established lodges among them in 1898. The source was Caddo, and nearly all the 800 full-bloods were ultimately peyote users; the Quapaw ceremony may also have had an influence upon them. The Caddo-Dela-ware messiah, John Wilson, came to the Osage in i9o2, after most of them around Hominy and elsewhere had known of it.57 The younger Osage who embraced the new religion could be distinguished from the conservatives in their wearing of braids decorated with ribbons and colored yarn, in place of the older roached style of headdress. In the last year or so an Osage named Morell has invited the Caddos Alfred Taylor and Ben Carter to bring the "Enoch" (Caddo) moon to his home; he already had a Wilson moon on his place, but his sons wanted to have the more basic Caddoan moon."

The Tonkawa first brought peyote to the Oto very long ago; Koshiway places this as far back as 1876 (which is not implausible in view of the earliest Kiowa and Comanche contacts with the plant). This must not be regarded, however, as the date of the vigorous functioning of the cult, but it is well to recall here the Oto mescal bean cult which may have facilitated the borrowing of the later narcotic.°

We have elaborated in an appendix the origin of the Christian elements in Oto peyo-tism, which spread to other Siouan groups (Omaha and Winnebago). The Church of the First-born embodied Russellite doctrines familiar to the Oto teacher Koshiway.° It was incorporated in 1914, though its roots may have gone back as far as 1896, apparently with some consultation with the Shawnee," and the consent of White Horn (Oto) leader of the older and already established native peyote ceremony. Its influence on the Native American Church and the Negro Church of the First,born is elsewhere discussed, as are also the specific Christian elements in peyotism as a whole. The famous meeting 14 miles east of Red Rock at which the Kiowa leaders Belo Kozad and Jack Sandkadote and an Apache named Star visited the Oto, was responsible for the amalgamation of the Church of the First-bom and the Native American Church. Dugan Black, leader of the first Oto meeting attended, is stated to have gotten his "road" from Little Henry (Kiowa) and uses Kiowa songs; another Oto leader uses Conklin Hummingbird's fireplace.

The Ponca are said by Shonle" to have gotten peyote from the Southern Cheyenne in 19o2-o4, but native information indicates that there were Comanche sources too (Ponca songs, e.g., are frequently Comanche). The Cheyenne, White Horse, brought them the cult in September, i9o4, but when they heard that it was recent among this group, they went to Quanah Parker among the Comanche "to get to the bottom of it." The late Robert Buffalolead was the earliest leader of the Cheyenne rite. A suggestion of Caddo influence appears again in the rules surrounding the drum; the typical Ponca peyote drum has a handle made of the twisted rope-end of the lacing. "The old people are strict, and you're not allowed to put your hand on the drum [head]," we were told.

Eagle Flying Above, who later became oil-wealthy, was the first Pawnee user of peyote, obtaining it from White Eyes, an Arapaho friend, about 1890 or a little later. Several months later Sun Chief, the writer's informant, took it up. At the death of Eagle Flying Above, Sun Chief was the only Pawnee leader, and all the others leamed the rite from him; he has eaten peyote since 1892-94, but only later became a leader. A still earlier source appears to be the Quapaw," whom two Pawnee youths visited in 189o, but the cult be-came vigorous only after further instruction from the visiting Arapaho. There was some opposition to peyote among the Pawnee in the early days: "they didn't understand it." The leaders of the opposition were Sky Chief, head of the Kuyau or "Doctor Dancers," and Good Buffalo, leader of the Buffalo Dance ceremonialists; later, however, both joined the peyote,users. The cult is found chiefly among the Pitahaufrata, where the form orig-inated, but found a later following among the Chauí, then the latkahlxki and a few Skidi.

It is interesting to note that, as with the Shawnee and others, Pawnee peyote was early involved in the Ghost Dance excitement. The leader claimed from peyote the same sort of revelations acquired in the Ghost Dance trance, and taught that while under the influence of peyote one could learn the rituals belonging to bundles and societies; in this manner he himself amassed considerable star lore. One unusual Pawnee feature was the use of a special Ghost Dance form of painted tipi for peyote meetings; minor changes were made in the type of drum and rattle also."

The Potawatomi first had peyote sometime between 1908 and 1914, but little else is known about it there. Quapaw peyotism derives from the Caddo-Delaware. The Ree" [Arikara] were strongly against the cult, and it apparently died out among them by 1924. Ed Butler brought Sauk" peyote directly from the Tonkawa :

In the early days women were not allowed to be members, and the manitou who gave the man this medicine made it a rule that it should be used [only] in wantime . . . It is only a war-bundle among other tribes.

But the Sauk have been tenacious of their older religion and its fetishes," though peyotism is now strong among them; indeed, about 1923, attempted affiliation with the Native American Church failed because five rival chiefs ran different meetings."

The Seminole have started the religion only recently, about the same time as the Chero‘ kee; they have learned it through the Yuchi, Caddo and Kiowa. George Anderson (Dela-ware) brought the Wilson moon to the Seneca in 1907, when eighteen men and women be-came members. One of the Seneca had a Quapaw wife, who gave him the idea of obtaining the moon; they were too poor to pay Anderson's usual fee, and merely gave him car-fare home."

The Shawnee Jim Clark received peyote from the Comanche in the late i89o's. Infor-mants say the Shawnee have had peyote as a plant for a long time, using it to keep from getting tired on the march, for moistening the mouth when dry-camping and to relieve hunger. The first Absentee Shawnee meeting was held by the Scotts in woo, under the tutelage of the Kickapoo. John Wilson was among the Shawnee about 1894, and George

Fourleaf (Delaware) brought peyote to White Oak from Mexico about 1898. Ernest Spy-buck got his moon from the Delaware near Dewey, while the Panthers are said to use the Yuchi manner. The majority of the Shawnee, however, use the standard Kiowa-Arapaho moon. Some Shawnee liken the leader's staff to the staff in the Green Corn Dance, and there is a legend of getting power from peyote which some say was not peyote but another plant which preceded it."

A Sioux introduced peyote to the Uintah and Ouray Agency."' The Ute around Fort Duchesne have used peyote "on the sly" since before 1916; the cult was vigorous around Randlette, Utah, by the spring of 1916. Mrs. Cooke attended a Ute meeting in 1937 about ten miles from Whiterocks; an informant told her that

sometimes they have a half moon instead of a crescent—depending on the size of the moon in the sky at that time. . . . They had twice had a moon which had eyes and a mouth made in it—this is "God peeping."

This last suggests a Caddoan "Big Moon" influence, but the motif of the changing moon must be Ute, as it is not encountered elsewhere. The Gosiute near the Salt Lake Desert began about i92i, as did the Paiute west of Salt Lake City. Little is known of these groups, but possibly Cheyenne teaching is responsible; Southern Ute visited Oklahoma peyote groups as early as 19io according to information of Dr. Parsons."

The Wichita, like the Shawnee, claim to have had peyote long before they learned to eat it in meetings. In one of their rain ceremonies they used a medicine bundle containing four objects: feathers, a little buckskin doll, a piece of flint and peyote. The ceremony was called hä.ctiag, "fire-people-around," and they sang all night for four nights to bring rain. The coming of the peyote ritual, therefore, aroused no hostility:

No Wichita was ever against it [Sly Picard says]; they couldn't be, as all our medicine men and women had peyote in their medicine—the whole tribe.

Yellow Bird (Wichita-Kichai) may have eaten peyote as early as 1889, before the Washita bridge between Anadarko and Gracemont was built, and Sly's father used it in 1892, learning it from the Caddo. But they were dissatisfied with the Caddo moon, and invited Frank Moitah (Comanche) and Salo (Kiowa) to teach them. Old Man Horse (Kiowa) is usually credited, however, with bringing peyote to the Wichita about 19°2.

In 1893 and 1894 the Winnebago John Rave visited peyote eaters in Oklahoma (though he had eaten it as early as 1889,) and again in 1901. On the return from his second trip he tried to introduce the religion, but without success save among a few of his own relatives.

In 1903 or 19°4 R.ave went to South Dakota, Minnesota and Wisconsin to preach the new religion; he had been visiting the Kiowa and Comanche, as well as the Oto. Somewhat later Jesse Clay was taught the rite at Winnebago by a visitor called Arapaho Bull, and Dick Griffin learned another version from the Osage at Pawhuska, at a time when John Wilson was there. Yellowbank said that the Winnebago of Nebraska got peyote from the Arapaho, and thence it came to the Winnebago of Wisconsin. Thunder Cloud was among those opposing it, but by 1914 nearly half the tribe were adherents."

The Yankton of South Dakota by 1916 had a peyote cult strong enough to warrant the sending to Congress of a petition to pass an anti-peyote bill signed with ninety-two names. The Yuchi affiliated with the Creek around Sapulpa and Kellyville, received peyote from the Cheyenne. Shonle cites three additional groups we have not yet included. These are the Shoshoni, who received peyote in 1919, the Sioux (19o9—to) and the Crow (1912). Comparisons of the present list with Shonle's gives on the whole earlier dates, yet this need not be considered in any sense a discrepancy. Shonle's data were based on govern-ment sources, and should stand as indicating the dates when the various cults became virile enough to attract official notice. Our own data, based on native sources, give on the other hand what are probably the earliest contacts and introductions of the rite, without reference to the number or percentage of adherents in any tribe. It is evident from them too that tentative starts and multiple origins are the rule rather than the exception, and Shonle's information and our own should be regarded as supplementary rather than contradictory.74

Although peyotism is gone or decadent among the Tarahumari and the Mescalero, it is still vigorously spreading in the United States and southern Canada. Conceivably it could spread until it embraced all Plains, Basin and Woodlands groups whose earlier cul-ture is sufficiently consonant with its concepts, and it may have soMe slender chance of spreading in the southern and eastern Pueblos and Plateau, but scarcely elsewhere, for both geographical and cultural reasons. The cult may be expected to spread for some time in the future, but when its inevitable decadence and probable ultimate disappearance will have been accomplished, we may have witnessed in it the last of the great intertribal reli-gious movements of the American Indian.

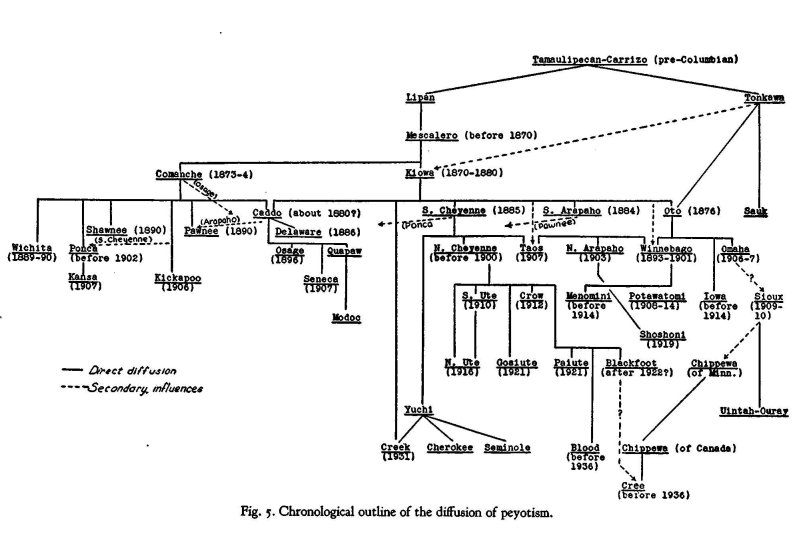

The present section sums up the external history of the diffusion of peyotism so far as it can be known from our Mexican sources, and in the Plains, where it appears that the pre-peyote mescal bean cult prepared the way somewhat for the use of the narcotic cactus.

The Plains rites are basically derived from the Kiowa, Comanche and Caddo peyote ceremonies, which in turn derive from the Mescalero Apache (whence the diffusion traces back to the Lipan and Tonkawa through the Carrizo perhaps to Tamaulipecan groups).

The Kiowa and the Comanche led in the diffusion of the standard aboriginal ceremony, but the Caddo variant was powerfully influenced by the individual, John Wilson, and diffused to the Osage, Quapaw, Delaware and others in a somewhat modified form. This is the subject of a special appendix.

The Oto are probably the crucial group in the diffusion of the later Christianized ver-sion of peyotism among such Siouan groups as the Winnebago and Omaha. Here again an individual gave a new turn to the ceremony by summing up in himself two streams of culture, the aboriginal and the Christian. Jonathan Koshiway is discussed in an appendix on the Native American Church, and a special appendix is devoted to the matter of Christian elements in the cult. The diagram on the opposite page sums up the external history of peyotism succinctly.

1. "These beans are often confused with those of a certain species of Erythrina, which are sometimes sold in their place in the markets of Mexico, but which are not at all narcotic" (Safford, Narcotic Plants, 397).

2 Not to be confused with the "mountain laurel" Kalmia latifolia.

3 Henry, The Plant Alkaloids, 395, 398.

4 Henry, op. cit., 397; cf. Safford, Narcotic Plants, 397.

5 Bellanger, in Havard (Bulletin 519: 6); Opler, The Autobiography; Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, r: 256; Bennett and Zingg, The Tarahumara, 358. The use of frijolillo in maguey liquor (which equates with mescal) probably accounts for the usage "mescal bean." Since the text was written further Apache material has ap-peared (Castetter and Opler, Ethnobiology of the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache, 54-55)-

6 Mooney, Miscellaneous Notes, 6. Schultes figures a Kiowa necklace of true mescal beans (Sophora secundiflora Ortega, Lag. ex DC.) strung on buckskin, with a piece of red ribbon, beaver fur and a child's ring enclosing a bundle of dried beaver-testis "medicine" in a lace handkerchief, as trinkets or amulets.

7 Skinner, Ethnology of the Ioway, 261; Gilmore, Uses of Plants, 99.

8 Skinner, Societies of the Iowa, 718-19.

9 Cf. the origin of peyote in deer's foot-prints or hooves.

10 "The mek6cutzi beans were supposed to be alive. Those I have seen in the possession of various Iowa were kept in a buckskin wrapper which was carefully perforated that they might see out." Cf. the ability of the father peyote to see.

11 Cf. the preparation of peyote by grinding on metates like com.

12 Cf. the black drink ceremony to the east, and the Plains Sun Dance.

13 Early peyotism was likewise an agricultural "first-fruits" rite.

14 The Wichita used mescal beans in horse-racing too. Cf. the use of peyote in racing and deer-hunting, and the use of datura in deer-hunting.

15 Cf. the fetishistic use of the father peyote in war.

16 Cedar and sage are likewise involved in peyotism.

17 Harrington, quoted by Skinner, Ethnology of the Ioway, 244-47.

18 Compare note 13.

19 The Delaware, Osage, Quapaw and Oto call the leader's peyote staff an "arrow," the Ponca a "bow."

20 Cf. peyotism's four ritual songs, and the whistling outside at midnight at the four points of the compass.

21 But Erythrina flabellifarmis contains no toxic alkaloids; see Appendix 2..

22 Did that truculent and little-known group, the Caddo, have the mescal cult?

23 Has this taboo any reference to the boneless meat of the peyote ritual breakfast?

24 Voegelin, Shawnee Field Notes.

25 The Huichol, for whatever such evidence is worth, in the mythological songs of their shamans, recite how the world began and how they were taught to hunt deer, to seek hikuli and to raise com (Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 2: 8). The route they take in gathering peyote is from beginning to end full of religious and mythological associations, and they meet their deities on the way in the shape of mountains, stones, springs, etc. (idem, 2: 132,). According to their traditions, they originated in the south, but got lost under the earth as they wandered northward, reappearing in the country of the hikuli (idem, 2: 23). Such deep-rooted symbolisms as theirs argues age.

26 Bennett and Zingg, The Tarahumara, 36o, 366-67, 379, 383, 386; Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, : 357— 358, 444 (but see I: 378).

27 Velasco, Dictamen Fiscal, 194; Opler, The Autobiography; Lipan Field Notes; The Influence of Aboriginal Pattern; Wagner, Entwicklung und Verbreitung. Opler says that peyote was introduced within the memory of the oldest living Mescalero; after 19io it was in decided decline.

28 Parsons, Taos Pueblo, 62-63. The origin legend is Kiowa. Mooney received a letter dated July 18, 1921 from the Taos Indian, Star Road, relative to trials of "peyote boys."

29 CoZio, Proceso.

30 In 1921 on the orders of the Governor, Manuel Cordova, a peyote meeting was raided and the blankets and shawls of all participants somewhat highhandedly confiscated. Prominent medicine-men refused to doctor "peyote boys" because the new religion was prejudicial to their vested interests. In 1923 two adherents of the cult were whipped, one twenty-five lashes, by the Lieutenant-Governor. Three men were fined $7oo, $800 and $rnoo, and the case ultimately reached the American court; the judge decided that the Governor had no right to impose such heavy fines, reversed the judgment and ordered the return of the property. This done, the officers resigned from office, and for a time there were no secular officers at Taos because no one wanted to take up the controversy. In 1931 the confiscated property taken ten years before had still not been returned, the Coun, cil refusing even to consider a $io fine in compensation; $21 was demanded for the return of each shawl and blanket.

31 Parsons, Taos Pueblo, 8o, note 64; 99, note 166; x 18; John Collier, in Peyote as Used in Religious Worship.

32 This widespread origin legend of the Plains is also Mescalero and Lipan, and from certain indications I suspect that it is Tamaulipecan also.

33 Mooney, in Handbook of the American Indians, 1: ryox, "Kiowa Apache."

34 MooneY, Peru Notebook, Ia.

35 Shonle, Peyote; The Giver of Visions, 54. Jack Sankadote, for example, was carried into a meeting as a baby by his father, and he is in his fifties.

36 Several older Kiowa patterns parallel peyote usages (e.g. the smoking ceremony of the Old Women's Society: leader west of central fire, lieutenants on either side of the door, five dishes of food from the fire east-ward; the Buffalo Medicine Men's Society bundle-repair meeting with a sage "stage," etc.), and the Kiowa-Comanche had the all night singing and beating on a rolled-up hide on the eve of departure on the war-path. But such parallels from the tribes one knows best lead to often naive particularistic explanations and should be guarded against. As a matter of fact it is the wide distribution of sweat bath doctoring and society meetings which accounts for the ease with which peyotism made its way in the Plains. The following two paragraphs are partly based on data gathered by Donald Collier, a colleague of the Laboratory of Anthropology Kiowa trip.

37 In judging the relative importance of the Kiowa and the Comanche in the diffusion of peyotism, one should recall that Comanche was historically the lingua Franca of the southern Plains. Quanah took peyote to the Caddo and Wichita it is said, though he was not the first to do so; he led meetings among the Cheyenne and the Arapaho in 1884. Petrullo (The Diabolic Root, 129) says he learned peyote about 1868 in Arizona, New Mexico and Old Mexico.

38 "it desirable to eat with the Comanche or the Kiowa because they are reputed to have learned of Peyote many years before the others." (Petrullo op. cit., 33.)

39 Handbook of the American Indians, 2: 87ob; cf. Mooney, in Peyote as Used in Religious Warship, 13-14, 15; Rouhier, Monographie, 102.

40 Jock Bullbear's and Mooney's testimonies in Peyote as Used in Religious Worship, 4o, 48, 57.

41. Kroeber, The Arapaho, 41o. The practice apparently is also Kiowa and Oto.

42 Wissler, Societies and Dance Associations, 436; the statement was made in conversation.

43 Newberne and Burke, Peyote: An Abridged Compilation, table.

44 Wagner, Entwicklung und Verbreitung, 84, footnote.

45 Newberne and Burke, op. Cit., 13 ff.

46 Petrullo, The Diabolic Root, 71-72.

47 Wilson said that one Smith had been in Oklahoma from a group on the Yukon River in southern Alaska; they were said to have used it for fifteen years. Jenness Oetter to Schultes) reported a rumor that a little peyote had filtered into Salishan groups of British Columbia but Gunther (letter to Schultes) reported its absence among the Flathead and Kutenai.

48 Hoebel, Northern Cheyenne Field Notes.

49 Letter from Fred Washington to Dr. F. G. Speck, April 1932.. Petrullo (The Diabolic Root, 165) says the Delaware got peyote from the Kiowa; there is obvious Caddo influence too, via John Wilson.

50 Skinner, Societies of the Iowa, 693-94, 724; Medicine Ceremony of the Menomini; Ethnology of the Ioway, no, 217, 248-49.

51 Skinner, Societies of the Iowa, 758.

52 "We the undersigned members of the Kickapoo Tribe of Indians in Kansas most earnestly petition you to help us keep out the pellote, or mescal, from our people. We realize that it is bad for us Indians to indulge in that stuff. It makes them indolent, keeps them from working on their farms, and taking care of their stock. It makes men and women neglect their families. We think it will be a great calamity for our people to begin to use the stuff . . . . We most urgently petition you that immediate action must be taken before the stuff gets hold of our people" (Seymour, Peyote Worship, 183).

53 Skinner, Medicine Ceremony of the Menomini, 24, 42-43, 97.

54 Speck, Delaware Peyote Symbolism.

55 Gilmore, The Mescal Society, 163-67; The Uses of Plants, to4-1o6; Mooney, Tarumari.Guayachic; Speck, Delaware Peyote Symbolism; testimony of Sloan in Peyote as Used in Religious Worship, 15. Murie, Pawnee Indian Societies, 637.

56 Peyote as Used in Religious Worship, ro—r 1, 3o-1 1, 43, 44-45. This booklet was compiled after rot 1, giving for "twenty years [agol" a maximally early date of 1891; but other internal evidence indicates a publica, tion date of 1916, giving the date 1896 as quoted.

57 Speck, Notes on the Ethnology, iv.

58 No doubt with the memory of the fate of Albert Stamp's attempted "moon" among the Caddo, Taylor exhibited considerable modesty when this flattering offer was made "I appreciate that offer," he said, "but I'm just Alfred Taylor, that's all I am, and I never did run a meeting, and I would rather you'd get somebody else from down home who runs meetings to do it for you." Several weeks later my informant said he didn't think Taylor would accept, though he might drum or build the fire "like a servant"—"He's afraid the Caddos will think he is pushing himself ahead too much, but he has even drummed for Enoch Hoag; he just don't like to jump ahead of everybody too much away from home." This abnegation is all the greater when it is understood that the Osage are accustomed to make handsome money gifts on such occasions.

59 Koshiway compared the smoke,meeting before the war path to peyote: "They have a meeting and smoke the pipe together and leave the next day. This clears up the enemies, and you can prophesy then. Peyote is similar to this—all night." Another older pattern interestingly survives among the Oto: in the informal morning period in the tipi, joking relationship seems to function.

60 One wonders if the Russellite eschatology was not made more acceptable historically among the Oto be, cause of an approximation to certain Ghost Dance notions. In any case, the curious prohibition on smoking may have symbolized, on the one hand, the rejection of older patterns of religious smoking, reinforced by the prohibi, tion of secular smoking too.

61 Mooney, Tarumari,Guayachic, 38.

62 Shonle, Peyote: The Giver of Visions, 55.

63 Murie, Pawnee Indian Societies, 636-37. Wagner (Entwicklung und Verbreitung, 75) disputes Shonle's statement that they got it from the. Quapaw, on the ground of the greater complexity of the Quapaw rite. His argument is unimpressive and a priori: John Wilson was the source of that complexity. Cf. Opler, The Auto, biography.

64 There may be Doctor Dance parallels in peyotism (e.g., an earthen altar, a fire in a round hole in the center of the tipi, doctoring at night with coals, fan or sucking horn, presence of the relatives of the patient in the meeting, etc.); another older Pawnee pattern in peyote may be the special morning prayer-maker south of the door.

65 "PEYOTE FAILS. It is a good thing that peyote is stopped for it was doing more harm than good. Our young men of the reservation were just beginning to start in eating the devil's root . . . Peyote fails because it has no mouth so can not speak to its followers of their origin and destiny, nor as to sin, repentance, forgive, ness, salvation nor of anything else. It has no ears, so can not hear prayer; it has no eyes, so it can not see a per, son's needs; no hands so can not help; no mind, so can not think. It is therefore unable to ask God for the thing which its worshipers need, and which they plead with it to implore God for. Our boys tried to make others be, lieve that peyote is a God and a religion, but if one wants to believe in mysterious things it must be Christ or peyote." (Sam Newman, Ree[Arikarab in The Indian Leader.)

66 Michelson, Sauk and Fox Myths.

67 Skinner, Observations on the Ethnology, 85.

68 Native American Church, President's Report, 1915.

69 Speck, Delaware Peyote Symbolism,

70 Voegelin, Shawnee Field Notes.

71 Peyote, An Insidious Evil, 3-4; Office of Indian Affairs, Discussion Concerning Peyote, 13.

72 Much of this information is from Alfred Wilson, a Southern Cheyenne'. His presidential report for 1925 (Sixth Annual Convention of the Native American Church) cites "locals" for the Caddo, Wichita, Pawnee, Arapaho, Yuchi, Kiowa, Oto, Shawnee, Ponca, Sauk and Fox, Cheyenne, and Omaha. Parsons, Taos Pueblo, 62; Willard Park informed me in 1936 that the Paviotso lacked peyote.

73 Radin, A Sketch of the Peyote Cult, 4-5, 7; The Winnebago Tribe, 394, 400, 415, 421; Crashing Thunder, 169—'70, in, t85; Lowie, Notes Concerning New Collections,289; Densmore, The Peyote Cult; Winnebago Songs of the Peyote Ceremony; Speck, Delaware Peyote Symbolism.

74 Seymour, Peyote Worship, 184; Petrullo, The Diabolic Root, 71-72; Shonle, Peyote; The Giver of ViSi071S, 55.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|