CHAPTER 1 The legislation of morality

| Books - The Legislation of Morality |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER 1 The legislation of morality

Introduction

THERE WAS ONCE A TIME WHEN ANYONE COULD GO TO his corner druggist and buy grams of morphine or heroin for just a few pennies. There was no need to have a prescription from a physician. The middle and upper classes purchased more than the lower and working classes, and there was no moral stigma attached to such narcotics use. The year was 190o, and the country was the United States.

Suddenly, there came the enlightenment of the twentieth century, full with moral insight and moral indignation, a smattering of knowledge of physiology, and the force of law. By 192o, the purchase of narcotics was not only criminal (that happened overnight in 1914), but some men had become assured that the purchase was immoral.

An important contemporary shibboleth is "You can't legislate morality." Its importance is not determined by the frequency of its use, but by the intensity of belief that Americans seem to invest in it and by the firmness with which they reject legal attempts to resolve certain moral issues. This single phrase is called forth to squelch arguments about issues from civil rights to temperance. The failure of Prohibition is usually cited dramatically as the final demonstration of the point. Its simplicity is matched by its deceptiveness; it is a short and concise statement containing only two elements. The first element is "legislate," whose meaning is quite clear. A bill passes in a legislative body and becomes a statute. The second part is "morality," and that is much less clear. Many things will be said later about the meaning of morality, but here we may sacrifice elaborated precision for quick agreement by asserting that morality refers to the strong feelings which people have about right and wrong. If we put these two together we can rephrase: "Passing a law can not change the strong feelings that people have about right and wrong."

The rephrasing is instructive because it frees the mind from the thought-channeling properties of the cliché. With the newly formed construction of the old idea, we find glaring problems that reveal inconsistency and confusion. For example, the moral middle classes will assert at one point that the legislation of morality is impossible, then turn around and take a passionate stand against the legalization of prostitution on the grounds that positive state sanction would undermine the moral structure of society. The belief is firm that the statutes greatly affect the way in which people will feel morally about prostitution. However, if one is capable of opposing, say, racial discrimination and extramarital sex on moral grounds, support of laws prohibiting both would be consistent and logical. Yet some will obviously support one kind of "moral" legislation and not another.

The relationship between law and morality is both complicated and subtle. This is true even in a situation where a society is very homogeneous and where one might find a large degree of consensus about moral behavior. Those who argue that law is simply the empirical operation of morality are tempted to use homogeneous situations as examples. In discussing this relationship, Selznick asserts that laws are secondary in nature.' They arc secondary in the scnse that they obtain their legitimacy in terms of some other more primary reference point.

The distinctively legal emerges with the development of secondary rules, that is, rules of authoritative determination. These rules, selectively applied, "raise up" the primary norms and give them a legal status.... The appeal from an asserted rule, however coercively enforced, to a justified rule is the elementary legal act. This presumes at least a dim awareness that some reason lies behind the impulse to conform, a reason founded not in conscience, habit, or fear alone, but in the decision to uphold an authoritative order. The rule of legal recognition may be quite blunt and crude: the law is what the king or priest says it is. But this initial reference of a primary norm to a ground of obligation breeds the complex elaboration of authoritative rules that marks a developed legal order.2

The most primary of reference points is, of course, the moral order. One can explain why he does something for just so long, before he is driven to a position where he simply must assert that it is "right" or "wrong." With narcotics usage and addiction, the issue in contemporary times is typically raised in the form of a moral directive, irrespective of the physiological and physical aspects of addiction. The laws concerning narcotics usage may now be said to be a secondary set held up against the existing primary or moral view of drugs. However, the drug laws have been on the books for half a century, during which time, as we shall see, this country has undergone a remarkable transformation in its moral interpretation of narcotics usage. Clearly, if we want to understand the ongoing relationship between the law and morality, we are misled by assuming one has some fixed relationship to the other. To put it another way, if a set of laws remains unchanged while the moral order undergoes a drastic transformation, it follows that the relationship of law to morality must be a changing thing, and cannot be static. If narcotics law was simply the empirical element of narcotics morality, a change in the moral judgment of narcotics use should be accompanied by its counterpart in the law, and vice versa. As Selznick points out:

In recent years, the great social effects of legal change have been too obvious to ignore. The question is no longer whether law is a significant vehicle of social change but rather how it so functions and what special problems arise.'

Selznick goes on to suggest explorations into substantive problems of "change." The connection of law to change is clearly demonstrable. If a society undergoes rapid technological development, new social relationships will emerge, and so too, will a set of laws to handle them. The gradual disintegration of the old caste relationships in India has been and will be largely attributable to the development of new occupations which contain no traditional forms regulating how one caste should respond to another.

The relationship of law to morality is not quite so clear. It is more specific, but more abstract. The sociological study of the narcotics problem is critical to discussion of this relationship, because it provides a specific empirical case where one can observe historically the interplay between the two essential components. More than any other form of deviance, the history of drug use contains an abundance of material on both questions of legislation and morality, and of the relationship between them.

Background and Setting

Despite the public clamor of the 196os about LSD and marijuana, the drug that has most dominated and colored the American conception of narcotics is opium. Among the most effective of painkillers, opium has been known and used in some form for thousands of years. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, opium was taken orally, either smoked or ingested. The Far East monopolized both production and consumption until the hypodermic needle was discovered as an extremely effective way of injecting the drug instantly into the bloodstream. It was soon to become a widely used analgesic. The first hypodermic injections of morphine, an opium derivative used to relieve pain, occurred in this country in 1856.4

Medial journals were enthusiastic in endorsing the new therapeutic usages that were possible, and morphine was the suggested remedy for an endless variety of physical sufferings. It was during the Civil War, however, that morphine injection really spread extensively. Then wholesale usage and addiction became sufficiently pronounced so that one could speak of an American problem for the first time.5 Soldiers were given morphine to deaden the pain from all kinds of battle injuries and illnesses. After the war, ex-soldiers by the thousands continued using the drug, and recommending it to friends and relatives.

Within a decade, medical companies began to include morphine in a vast number of medications that were sold directly to consumers as household remedies. This was the period before governmental regulation, and the layman was subjected to a barrage of newspaper and billboard advertisements claiming cures for everything from the common cold to cholera. "Soothing Syrups" with morphine often contained no mention of their contents, and many men moved along the path to the purer morphine through this route.

It is not surprising that many persons became dependent on these preparations and later turned to the active drug itself when accidentally or otherwise they learned of its presence in the "medicine" they had been taking.... The peak of the patent medicine industry was reached just prior to the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906.6

It must be remembered that there were no state or federal laws concerning the sale and distribution of medicinal narcotic drugs during this period under discussion, and pharmacists sold morphine simply when it was requested by a customer. There is no way to accurately assess the extent of addiction at that time, nor is there now, for that matter. However, there are some informed estimates by scholars who have studied many facets of the period. Among the better guesses many will settle for is that from 2 to 4 per cent of the population was addicted in 1895.' Studies of pharmaceutical dispensaries, druggists, and physicians' records were carried out in the 188os and 189os which relate to this problem. The widespread use of morphine was demonstrated by Hartwell's survey of Massachusetts druggists in 1888,9 Hull's study of Iowa druggists in 1885,9 Earle's work in Chicago in 188o,1O and Grinnell's survey of Vermont in 190o." The methodological techniques of investigation do not meet present-day standards, but even if certain systematic biases are assumed, the 3 per cent figure is an acceptable guess of the extent of addiction.

The large numbers of addicts alarmed a growing number of medical men The American press, which had been so vocal in its denunciation of the sensational but far less common opium smoking in opium dens in the i86os and 18705, was strangely if typically silent on morphine medication and its addicting effects. Just as the present-day press adroitly avoids making news of very newsworthy government proceedings on false advertising (an issue in which there may also be some question of the accomplice), newspapers of that time did not want to alienate the advertisers, because they were a major source of revenue. Nonetheless, the knowledge of the addicting qualities of morphine became more and more common among a sizable minority of physicians.

It was in this setting, in i 898, that a German pharmacological researcher named Dreser produced a new substance from a morphine base, diacetylmorphin, otherwise known as heroin. The medical community was enthusiastic in its reception of the new drug. It had three times the strength of morphine, and it was believed to be free from addicting qualities. The most respectable medical journals of Germany and the United States carried articles and reports lauding heroin as a cure for morphine addiction.12

Within five short years, the first definitive serious warnings about the addicting qualities of heroin appeared in an American medical journal.13 The marvelous success of heroin as a painkiller and sedative, however, made the drug popular with both physician and patient. It should be remembered that one did not need a prescription to buy it. The news of the new warnings traveled slowly, and heroin joined morphine as one of the most frequently used pain remedies for the ailing and suffering.

From 1865 to 1900, then, addiction to narcotics was relatively w ide-spread. This is documented in an early survey of material by Terry and Pellens, a treatise which remains the classic work on late nineteenth-and early twentieth-century problems of addiction.14 In proportion to the population, addiction was probably eight times more prevalent then than now, despite the large increase in the general population.

It is remarkable, therefore, that addiction is regarded today as a problem of far greater moral, legal, and social significance than it was then. As we shall see directly, the problem at the turn of the century was conceived in very different terms, treated in a vastly different manner, and located in opposite places in the social order.

The first task is to illustrate how dramatic and complete was the shift of addicts from one social category to another during a critical twenty-year period. The second task is to examine the legal activity which affected that shift Finally, the task will be to examine the changing moral judgments that coincided with these developments.

It is now taken for granted that narcotic addicts come primarily from the working and lower classes. (In Chapter 7, a description of the contemporary addict population corroborates this for the number known and apprehended.) This has not always been true. The evidence clearly indicates that the upper and middle classes predominated among narcotic addicts in the period up to 1914. In 1903, the American Pharmaceutical Association conducted a study of selected communities in the United States and Canada. They sent out mailed questionnaires to physicians and druggists, and from the responses, concluded that

while the increase is most evident with the lower classes, the statistics of institutes devoted to the cure of habitues show that their patients are principally drawn from those in the higher walks of life. ...1 s

From a report on Massachusetts druggists published in 1889 and cited by Terry and Pellens, the sale of opium derivatives to those of higher incomes exceeded the amount sold to lower-income persons.16 This is all the more striking if we take into account the fact that the working and lower classes comprised a far greater percentage of the population of the country in 1890 than they do today. (With the 196o census figures, the population of the United States becomes predominantly white collar for the first time in history.) In view of the fact that the middle-class comprised proportionately less of the population, the incidence of its addiction rate can be seen as even more significant.

It was acknowledged in medical journals that a morphine addict could not be detected as an addict so long as he maintained his supply." Some of the most respectable citizens of the community, pillars of middle-class morality, were addicted. In cases where this was known, the victim was regarded as one afflicted with a physiological problem, in much the same way as we presently regard the need of a diabetic for insulin. Family histories later indicated that many went through their daily tasks, their occupations, completely undetected by friends and relatives.18

There are two points of considerable significance that deserve more careful consideration. The first is the fact that some friends and relatives could and did know about an addiction and still did not make a judgment, either moral or psychological, of the person addicted. The second is that the lower classes were not those primarily associated with morphine or heroin usage in woo.

The moral interpretation of addiction in the twentieth century is especially interesting in view of the larger historical trend. Western man has, on the whole, developed increasing tolerance and compassion for problems that were previously dogmatically treated as moral issues, such as epilepsy, organic and functional mental disorders, polio, diabetes, and so on. There was a time when most were convinced that the afflicted were possessed by devils, were morally evil, and inferior. Both medical opinion and literature of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were replete with the moral interpretation of countless physiological problems which have now been reinterpreted in an almost totally nonmoral fashion. The only moral issue now attendant to these questions is whether persons suffering should receive treatment from physicians. Even venereal diseases, which retain a stigma, are unanimously conceived as physiological problems that should be treated physiologically irrespective of the moral conditions under which they were contracted.

The narcotic addict of the 1890s was in a situation almost the reverse of those suffering from the above problems. His acquaintances and his community could know of his addiction, feel somewhat sorry for his dependence upon medication, but admit him to a position of respect and authority. If the heroin addict of 590o was getting a willful thrill out of his injection, no one was talking about either the willful element or the thrill, not even the drug companies. If the thrill was to be had, there was no reason for manufacturers not to take advantage of this in their advertisements. They had no moral compunctions about patently false claims for a cure, or about including an opium derivative without so stating on the label.

Despite the fact that all social classes had their share of addicts, there was a difference in the way lower class addicts were regarded. This difference was exacerbated when legislation drove heroin underground, predominantly to the lower classes. Writing in the American Journal of Clinical Medicine in 1918, G. Swaine made an arbitrary social classification of addicts, about which he offered the following distinction:

In Class one, we can include all of the physical, mental and moral defectives, the tramps, hoboes, idlers, loaders, irresponsibles, criminals, and denizens of the underworld.... In these cases, morphine addition is a vice, as well as a disorder resulting from narcotic poisoning. These are the "drug fiends." In Class two, we have many types of good citizens who have become addicted to the use of the drug innocently, and who are in every sense of the word `victims." Morphine is no respecter of persons, and the victims are doctors, lawyers, ministers, artists, actors, judges, congressmen, senators, priests, authors, women, girls, all of who realize their conditions and want to be cured. In these cases, morphine-addiction is not a vice, but, an incubus, and, when they are cured they stay cured.19

This may seem to jump ahead of the task of this section, which is simply to portray as accurately as possible the dramatic shift of addicts from one social category to another during this period. However, the shift itself carried with it more than a description. These were the beginnings of moral interpretations for the meaning of that shift. By 192o, a medical journal reported cases treated at Riverside Hospital in New York City in the following manner:

Drug addicts may be divided into two general classes. The first class is composed of people who have become addicted to the use of drugs through illness, associated probably with an underlying neurotic temperament. The second class, which is overwhelmingly in the majority [italics mine], is at the present time giving municipal authorities the greatest concern. These persons are largely from the underworld, or channels leading directly to it. They have become addicted to the use of narcotic drugs largely through association with habitues and they find in the drug a panacea for the physical and mental ills that are the result of the lives they are leading. Late hours, dance halls, and unwholesome cabarets do much to bring about this condition of body and mind. ...20

Whereas in 1900 the addict population was spread relatively evenly over the social classes (with the higher classes having slightly more), by 1920, medical journals could speak of the "overwhelming" majority from the "unrespectable" parts of society. The same pattern can be seen with the shift from the predominantly middle-aged to the young, and with the shift from a predominance of women to an overwhelming majority of men.

In a study reported in 1880 and cited by Terry and Pellens, addiction to drugs was said to be "a vice of middle life, the larger number, by far, being from 3o to 4o years of age."21 By 192o, Hubbard's study of New York's clinic could let him conclude that:

Most, in fact 70 per cent of the addicts in our clinic, are young people ... the one and only conclusion that we can arrive at, is that acquirements of this practice—drug addiction—is incident to propinquity, bad associates, taken together with weak vacillating dispositions, making a successful combination in favor of the acquirement of such a habit.22

A report of a study of addiction to the Michigan State Board of Health in 1878 stated that, of 1,313 addicts, 803 were females, SIo males.23 This is corroborated by Earle's study of Chicago, reported in 1880:

Among the 235 habitual opium-eaters, 169 were found to be females, a proportion of about 3-to-I. Of these 169 females, about one-third belong to that class known as prostitutes. Deducting these, we still have among those taking the different kinds of opiates, 2 females to I male.24

Similarly, a report by Hull in 1885 on addiction in Iowa lists the distribution by sex as two-thirds female, and Terry's research in Florida in 1913 reported that 6o per cent of the cases were women.25 Suddenly, as if in magical correspondence to the trend cited above on social class and age, the sex distribution reversed itself, and in 1914, McIver and Price report that 7o per cent of the addicts at Philadelphia General Hospital were males.2ó A governmental report to the Treasury Department in 1918 found addicts about equally divided between both sexes in the country, but a 192o report for New York conclusively demonstrated that males were by then the predominant sex among drug addicts. Hubbard's report indicated that almost 80 per cent of the New York Clinic's population of addicts were male.27 The Los Angeles Clinic had a similar distribution for 192o and 1921. The picture is clear. Taking only the three variables of age, sex, and social class into account, there is a sharp and remarkable transformation to be noticed in the two-decade period at the turn of the century. Let us examine now the legal turn of events of the period.

Prior to 1897, there was no significant legislation in any state concerning the manufacture or distribution of narcotics. As we have seen, the medical profession was becoming increasingly aware of the nature of morphine addiction when heroin was discovered in 1898. The alarm over the common practice of using morphine for a myriad of ills was insufficient to stem the tide of the great enthusiasm with which physicians greeted heroin. Nonetheless, a small band of dedicated doctors who had been disturbed by the widespread ignorance of morphine in the profession (warnings about addiction did not appear in medical texts until about 1900) began to agitate for governmental intervention and regulation.28

From 1887 to 1908, many states passed individual laws aimed at curbing some aspect of the distribution of narcotics. Opium smoking was a favorite target of most of these laws, a development occasioned by the more concentrated treatment given this issue in the American press. Nonetheless, many of the state legislatures listened to medical men who insisted on the need for more control on the widespread distribution of the medicinally used opium derivatives. New York's state legislature passed the first comprehensive piece of legislation in the country concerning this problem in 2904, the Boylan Act.

As with many other problems of this kind, the lack of uniform state laws meant that control was virtually impossible. There is great variety in the law-making ability of each state, and sometimes it seems as though each state reviews the others carefully in order not to duplicate the provisions of their laws. If New York wanted registration of pharmacists, Massachusetts would want the registration of the central distributing warehouses, Illinois might want only physicians' prescriptions, and so forth. It soon became clear that only national and even international centralized control would be effective.

At the request of the United States, an international conference on opium was called in early 1909. Among countries accepting the invitation to this convention held in Shanghai were China, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Japan. Prior to this time, there had been a few attempts at control by individual nations in treaties, but this was the first concerted action on a truly international level. The major purpose of this first conference, as well as two other international conventions that were called within the next four years, was to insure that opium and related drugs be distributed only for expressly medical purposes, and ultimately distributed to the consumer through medical channels. The conferences called for regulation of the traffic at ports of entry, especially, but also tried to deal with the complicated problem of mail traffic. The handful of nations represented at the first Shanghai conference recognized the need for obtaining agreement and compliance from every nation in the world. The United States found itself in the embarrassing position of being the only major power without any control law covering distribution of medicinal narcotics within its borders. (The 1909 federal law was directed at opium smoking.) It was very much as a direct result of participation in the international conventions, then, that this country found itself being pressed for congressional action on the problem.

In this climate of both internal and international concern for the medicinal uses of the opium derivatives, Congress passed the Harrison Narcotic Act, approved December 17, 1914.

The Harrison Act stipulated that anyone engaged in the production or distribution of narcotics must register with the federal government and keep records of all transactions with drugs. This was the first of the three central provisions of the act. It gave the government precise knowledge of the legal traffic, and for the first time, the various uses and avenues of distribution could be traced.

The second major provision required that all parties handling the drugs through either purchase or sale pay a tax. This was a critical portion, because it meant that enforcement would reside with the tax collector, the Treasury Department, and more specifically, its Bureau of Internal Revenue. The Bureau set up a subsidiary organization to deal with affairs related to surveillance of activities covered by the new law. The immediate task was to insure that drugs were registered and passed through legitimate channels, beginning with importation and ending with the consumer. Since everyone was required to keep a record, the Bureau could demand and survey documentary material at every stage of the market operation.

Finally, the third major provision of the Harrison Act was a subtle "sleeper" that was not to obtain importance until the Supreme Court made a critical interpretation in 1919. This was the provision that unregistered persons could purchase drugs only upon the prescription of a physician, and that such a prescription must be for legitimate medical use. It seemed innocent enough a provision, one that was clearly included so that the physician retained the only control over the dispensation of narcotics to the consumer. As such, the bill was designed by its framers to place the addict completely in the hands of the medical profession.

It is one of those ironic twists that this third provision, intended for one purpose, was to be used in such a way as to thwart that purpose. As a direct consequence of it, the medical profession abandoned the drug addict. The key revolved around the stipulation that doctors could issue a prescription only to addicts for legitimate medical purposes. The decision about what is legitimate medical practice rests ultimately outside the medical profession in the moral consensus which members of society achieve about legitimacy. Even if the medical profession were to agree that experimental injections of a new drug on a random sample of babies would do most to advance medical science, the moral response against experimentation would be so strong as to destroy its claim to legitimacy. Thus, it is only in arbitrary and confined hypothetical instances that we can cogently argue that the medical profession determines legitimate practice.

So it was that the germ of a moral conception, the difference between good and evil or right and wrong, was to gain a place in the exercise of the new law.

Since the Harrison Act said nothing explicitly about the basis upon which physicians could prescribe narcotics for addicts, the only theoretical change that was forseeable was the new status of the prescription at the drug counter. All sales were to be registered, and a signed prescription from a physician was required. But when the physician became the only legal source of the drug supply, hundreds of thousands of law-abiding addicts suddenly materialized outside of doctors' offices. It was inconceivable that the relatively small number of doctors in the country could so suddenly handle over half a million new patients in any manner, and certainly it was impossible that they might handle them individually. The doctor's office became little more than a dispensing station for the addict, with only an infinitesimal fraction of addicts receiving personal care. In most cases, this was simply a continuation of the small number who had already been under regular care.

In New York City for example, it was impossible for a doctor with even a small practice to do anything more than sign prescriptions for his suddenly created large clientele. The government agents were alarmed at what they regarded as cavalier treatment of the prescription by the medical profession, and were concerned that the spirit and intent of the new drug law were being violated. They decided to prosecute some physicians who were prescribing to addicts en masse. They succeeded in convicting them, and appeals took the cases up to the Supreme Court. In a remarkable case (Webb vs. U.S., 1919) the Supreme Court made a decision that was to have far-reaching effects on the narcotics traffic, ruling that:

a prescription of drugs for an addict "not in the course of professional treatment in the attempted cure of the habit, but being issued for the purpose of providing the user with morphine sufficient to keep him comfortable by maintaining his customary use" was not a prescription in the meaning of the law and was not included within the exemption for the doctor-patient relationship.29

Doctors who continued to prescribe to addicts on anything but the most personal and individual basis found themselves faced with the real, demonstrated possibility of fines and prison sentences. As I have indicated, there were hundreds of thousands of addicts, and only a few thousand physicians to handle them. If there were thirty or forty addicts outside a doctor's office waiting for prescriptions, or even waiting fora chance to go through withdrawal, the Supreme Court decision and the Treasury Department's actions made it almost certain that the doctor would turn them away. A minority of doctors, some for humanitarian reasons, some from the profit-motive of a much higher fee, continued to prescribe. Scores of them were arrested, prosecuted, fined, imprisoned, and set forth as an example to others. The addict found himself being cut off gradually but surely from all legal sources, and he began to turn gradually but surely to the welcome arms of the black marketeers.

And so it was that the law and its interpretation by the Supreme Court provided the final condition and context for a moral reassessment of what had previously been regarded as a physiological problem. The country could begin to connect all addicts with their new-found underworld associates, and could now begin to talk about a different class of men who were consorting with criminals. The step was only a small one to the imputation of criminal intent. The bridge between law and morality was drawn.

At this time, there were some men in the Treasury Department who momentarily recognized the impossible situation of the addict, and the government moved to allow temporary clinics in various cities throughout the country. The purpose at the outset, according to a Bureau report, was to provide an interim period where the addict could get his supply under some kind of medical supervision and not fall prey to the exhorbitant prices of the drug peddlers. Thus were born the controversial Narcotics Clinics that would total forty-four in only sixteen months, and spread to almost every major city in the nation. Closed abruptly by government order in 1922, they have remained as the focal point of the most heated disputes in the United States narcotic policy for the last forty years.

The clinics opened in 1918, and very little is known about most of them, a condition extremely conducive to passionate debate. Those who are against clinics usually cite the literature of the Federal Narcotics Bureau (established in 193o), a literature which is sketchy, poorly documented, and full of moralistic condemnation. In a 1920 report, the Treasury Department had this to say about the problem:

Some of the so-called clinics that have since been established throughout the country without the knowledge or sanction of this Bureau apparently were established for mercenary purposes or for the sole purpose of providing applicants with whatever narcotic drugs they required for the satisfaction of their morbid appetites. Little or no attempt was made by some of these private clinics to effect cures, and prominent physicians and scientists who have made a study of drug addiction are practically unanimous in the opinion- that such clinics accomplish no good and that the cure of narcotic addiction is an impossibility unless accompanied by institutional treatment."

There is no documentation given for these "studies" by prominent physicians and scientists who all agreed upon the issue in question. The reference to "morbid" appetites of addicts reflects a judgment of addiction from an agency of government, not from medicine.

Those in favor of the clinics have equally little evidence from the history of the period upon which to base their position. But as Linde-smith points out, where there is information available, and where there is conflict between the two camps, those who claim that the clinics were a relative success have the better of ií.31 The best case in point is the Shreveport, Louisiana clinic. Markedly conflicting reports from the Narcotics Bureau and Terry and Pellens give a clear indication that distortion and falsification are common in the former.32

Undoubtedly, some of the clinics were bad ones, guilty of the abuses that the Bureau cites. Some physicians were unscrupulous and prescribed drugs for an extra fee, taking advantage of the addict's inability to obtain the drugs at a lower price on the black market. But some of the clinics were good ones in the sense that the abuses were few, and that men were able to continue their normal lives without being drawn into illegal associations with peddlers, and perhaps driven to a life of crime.

Abuses in the New York City clinic and the attendant newspaper sensationalism brought about an atmosphere of panic in the general public. The large number of addicts in New York made it impossible for the clinic to handle each case individually. This was a fault of the available facilities, of course, and not of the clinic system. Hundreds and hundreds of addicts would line up outside the clinic in the early morning for their supply, the queue stretching for several city blocks on some days. The staff physicians simply prescribed as quickly as they could, not being able to afford to take the necessary time to check records thoroughly for complete identification, registration, and the like. So, some addicts would get their supply for the day, then go back and get in line a few more times so that they would not have to come back so often. The New York newspapers of the time, in the heyday of yellow journalism, sent out reporters. They documented some of the abuses of the New York clinic, but gave such sensational accounts that clinics in general were portrayed as sinful places where the addict could go to satisfy his "morbid" desires and pursue the thrills and pleasures of narcotics. The stories were picked up by papers in various parts of the country, and the public responded with moral outrage.

Letters severely critical of the clinic system flooded into magazines and newspapers, and few people had enough positive information to defend it. The American Medical Association officially deplored the situation, and took a firm position against ambulatory treatment of addicts. It was opposed to addicts coming to and going from hospitals or clinics while under treatment. The only alternative was complete institutionalization of the addict, since physicians could hardly be expected to treat the patient in his home, and police his actions to make sure he remained there. The government began closing the clinics in 192o, and had closed all but one by the middle of 1921.

Even while the clinics were open, the illicit traffic in narcotics was gaining ground. With the closing date, many more addicts were eligible prey for the black market peddlers.

The Federal Narcotics Bureau claims that the clinics aggravated the problem of drug addiction. Since there is no evidence of addiction spreading during the clinic period, one wonders what kind of criteria are used.

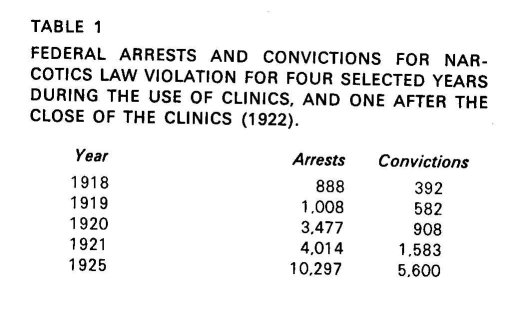

In 1918, the year before any clinics were opened, 888 federal arrests and 392 convictions for narcotics offenses were reported. In 1919, the year in which the New York Clinic operated and others were opened, arrests totaled 1,008 and convictions 582. In 1920, when the clinics, including the one in New York, were being closed, arrests rose to 3,477 and convictions to 908. In 1921, when the Prohibition Commissioner reported in June that all clinics were closed (one exception), arrests had risen further to 4,014 and convictions to 1,583. The yearly rise continued to a peak in 1925, when the clinics had been closed for several years with 10,297 federal arrests and 5,600 convictions.33

Today, men make an almost complete association of the addict with criminality. When we hear that someone is addicted to drugs, we seldom think of the physiological problem first. Instead, we conceive of an immoral, weak, psychologically inadequate criminal who preys upon an unsuspecting population to supply his "morbid" appetite. There is no exaggeration here. A pamphlet put out by the Public Health Service of the federal government in 1951, entitled "What to Know about Drug Addiction," had this to say of the addicts the society has come to think of as typical:

Usually, they are irresponsible, selfish, immature, thrill-seeking individuals who are constantly in trouble—the type of person who acts first and thinks afterward. The majority of addicts do not fall clearly into either the neurotic or character disorder groups but have characteristics of both classes.34

This is the character-disorder addict, and as the pamphlet indicates, the line between this type and the neurotic is very hard to draw, especially when conceived primarily in moral terms.

The maximum penalty under the Harrison Act was ten years imprisonment. The issues had so shifted in four decades, however, that Congress could pass two bills in the 195os drastically increasing the punishment. Under the old law, the judge could be flexible in sentencing, but the Boggs Amendment in 1951 set mandatory minimums that increased the prison sentence to ten years with repeated offenses. Then in 1956, Congress passed the Narcotic Drug Control Act that allowed the death penalty for sale to minors. This law also made distinctions between the user and the seller, with the latter singled out for harsher treatment. However, since a very large proportion of addicts sell at some time in order to help supply their habit, judges often have the option of invoking whichever provision they regard as appropriate.

Individual states were very busy during this period passing laws of their own on the sale and distribution of heroin. Many states even went so far as to make laws which made being an addict a crime. Despite a recent Supreme Court decision in 1962 ruling this unconstitutional, there is some confusion about this, especially when it comes down to the practice of the police. Illegal possession is a crime, and an addict would almost have to be in possession by definition. The police need only observe him for a period of twenty-four hours to make their case.

Certain social categories lend themselves more to moral condemnation than others. Whereas the lower and working classes had the smallest proportion of addicts in 1900, in 1969 they constituted the overwhelming majority of known addicts. Whereas Blacks were less than w per cent of the addict population in 1900, they are now more than half of the addicts known to law enforcement agencies. Whereas there were formerly more women than men addicted, the ratio is now at least seven to one for men. Whereas the middle-aged predominated in 1900, youth is now far and away the most likely of known offenders. The list could go on, but the point is simply that middle America's moral hostility comes faster and easier when directed toward a young, lower-class Negro male, than toward a middle-aged, middle-class white female.

The law drastically altered the conditions that produced the shifts in these categories. It is a short trip across the bridge to a moral judgment.

The present morality is so strong that it lets local policy justify apprehending an addict, putting him behind bars for hours upon hours, and forcing him to go through the most excruciating kinds of agony without medical treatment, in order that he inform on his supplier. In a later section, some time will be spent on the physiology of addiction and withdrawal. For the time, it is sufficient to call attention to the fact that for an addict to go through withdrawal from the drug with no treatment is a hell he wants to avoid so badly that he may cheat, steal, prostitute himself, sometimes even kill. The police know this, and take full advantage of it when a local crime has been committed for which some local addicts may have information. The moral judgment is so serious that it allowed a state's attorney of a major city who is a former law professor to say in open hearings:

In view of my background as a law professor, I am very jealous of civil rights, civil rights of individuals. One of the things I determined when I got in here was that I was going to be particularly careful about that. I must say this to you, that where narcotics addicts are concerned, I haven't many complaints, though I do know the police are a little prone to pick up these men. They have protection of an ordinance, and I must say that the problem is so serious that even if we must admit some of their civil laws or civil rights are being violated, you have to go along with a certain amount of fringe violation, if you see what I mean.3 5

The man speaking was John Gutknecht, State's Attorney for Cook County, Illinois, a man who handled the prosecution of addicts for Chicago. Gutknecht was talking to Senator Price Daniel in the above exchange, and went on to say:

So I think you will find that a lot of these arrests and subsequent discharges are in the form of a security measure that possibly we should not countenance, but I don't know how else you can function.

SENATOR DANIEL: You completely answered my next question. My next question was going to be this: How do you reconcile the large number of arrests for Chicago for the period 1953 and 1954, 6,643 with convictions 3,35o, just barely over fifty per cent of the arrests, and I believe you have answered it already.

MR. GUTKNECHT I think you will also have to agree that neither Mr. Tieken in his capacity nor I in my capacity—and we both have civil rights laws to enforce—can, with our multiple jobs, get too excited if a known addict has been unlawfully arrested and then discharged, knowing that because he is a known addict the police have to take little extra measures.3e

Here we see a swing of the full circle. Up until this point, I have attempted to demonstrate the dynamic relationship between legislation and morality. The circle is closed when agents of law enforcement take moral positions that influence differential legal treatment of the population. We "can't get too excited," said the State's Attorney, if drug addicts have their civil rights violated.

In view of these later developments, perhaps the most interesting feature of the early federal legislation was that its proponents did not advocate it out of a moral zeal. The medical men who pressed so forcefully for control on narcotics did not do so out of the moral conviction that addicts should be cut off from their supply of narcotics. Rather, their explicit intention was to prevent the widespread distribution of morphine and heroin to a public that was unsuspecting of its addicting qualities. The scholarly, lay, and medical literature of the period contained warnings about the physiological and sometimes psychological problems that were associated with drugs, and only on rare instances did it engage or address the moral issue of addiction.

The legislation brought about the conditions that were conducive to a reinterpretation of narcotics usage into almost purely moral terms. As long as the sale of morphine and heroin was legitimate, it was not in the interest of any man, or any entrepreneurial class of men, to make a large profit by hiking their own price of the drug above that of the going market. The laws, in pushing heroin into the underworld, suddenly made it extremely profitable to raise the price to an exhorbi- tant level because the addict would pay any price to keep from going through withdrawal from the drug. Consequently, any addict dealing with the black market was automatically placed in a class of lawbreakers, and he was associated with the underworld and its "immoral" non middle-class elements. Overnight, the conditions were ripe for treating the addict in moral terms. As soon as he could be classed with the undesirables, the nature of his problem could be transformed in the minds of men who were not addicts and who could not understand it.

Suggested Relationship Between Effects of Law in "Moral Areas"

This concluding section will present an introductory theoretical statement suggesting the different effects of law in different kinds of "moral" situations in which the law is violated. At the beginning of this chapter, it was pointed out that those who argue that morality can not be legislated are inconsistent in their observation of the moral-legal issues in the three social problem areas of prostitution, drug addiction, and racial discrimination. One may challenge the comparability of these three problems with some justification. With racial prejudice and discrimination, for example, men already have strong feelings by definition, and the issue is whether law would achieve a change in the direction desired by the legislators. Prior to 190o, quite the opposite state of affairs existed as to drug use, in that men did not feel strongly about heroin consumption. The federal law of 1914 was therefore enacted prior to strong moral judgment about heroin use per se. However, it did have the effect of pushing heroin into an arena where strong moralistic feelings existed. (Heroin use came to be associated with the "dregs of the cities" and sensual gratification; it came to be thought of in the same moralistic manner as the opium dens.) By the 193os, narcotics had joined prostitution and alcoholism as major moral problems in the minds of Americans.

Those who take the position that morality can not be legislated usually favor laws that support the existing moral order, such as their support of laws against prostitution and heroin use. The law is thereby conceived to be a kind of dam that is constructed after moral judgments are developed. The dam acts to hold back the floodtides of a contrary morality (its source unaccounted for), and consequently is seen as necessary to preserve the existing moral order.

This position, summarized immediately below, assumes that once moral judgments are firm, law cannot change morality, but that law can contain and prevent existing morality from changing.

1. Laws which supplement the existing moral order may be effective in preventing the spread of behavior that is immoral (prostitution);

2. laws which create the conditions for the development of a new morality may be successful in creating a new set of moral attitudes about behavior (e.g., drug use in 1914); but

3. laws which attempt to change the existing moral order are doomed to failure (e.g., Prohibition and racial discrimination).

Various modifications are required with points one and two preceding, but for the most part there is substantial agreement about their validity and they have some empirical basis. A major issue to be examined theoretically and empirically in the work is whether the third position stated is an accurate assessment of what men believe, or whether it is an empirical regularity itself that may prove to be a generalization about the way law and morality are related. It is a sociological axiom that what men believe is intricately interwoven with the patterns of their behavior. A primary concern of this book is a clarification of the law-morality issues now clouded by this question.

Raymond Mack once proposed that the effectiveness of a new law directed at a change of social behavior was dependent upon how strongly people felt about the object of the change.37 He used the example of legislation outlawing the use of a certain kind of match compared with legislation outlawing discrimination. People are not likely to rise up in arms if they are prohibited from buying cardboard matches in favor of wooden ones, or vice versa. The strong historical resistance to civil rights legislation was his opposite case in point. Mack's example of people's reaction to match-buying laws was admittedly not a case of a moral area of behavior, since it was chosen to make that point. Emotional investments are insignificant in this case. But what of instances where there is a question of altering the moral order? What other things can be said to influence the effectiveness of legislation?

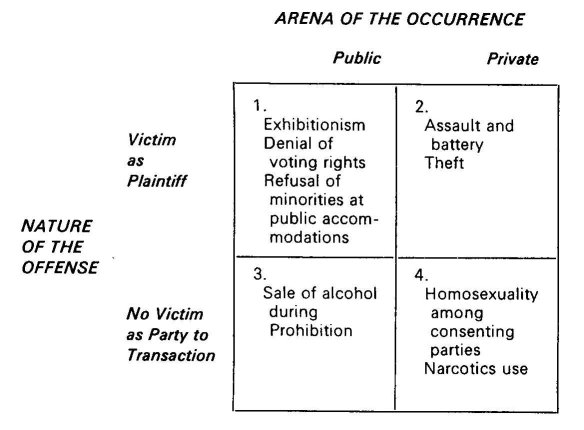

There are two dimensions that I would like to suggest as critical to these questions. The first concerns whether or not the violation involves a victim who can act as a plaintiff. Edwin Schur has examined this dimension in another context.38 His analysis of many aspects of "victimless" crimes is extensive and thorough. It suits the purpose here to explore further the question of victims of crimes as it relates to the issue of the possibility of effective law. In a case of assault and battery, the reaction of the society can be swift and firm for the simple reason that an individual can come forward, press charges, and demand redress of his grievance. Contrast this with the behavior of consenting adult homosexuals. There is no plaintiff to protest the action, even though it is just as much in violation of the written law as assault. Some of the consequences of this for law enforcement are immediately obvious, but some are not. Lindesmith has made the same point about the transaction between buyer and sellers of black market narcotics.39 Neither party to the transaction has it in his self-interest to inform legal authorities, and so the action could ordinarily go undetected and thus unpunished. However, where there is no victim who will act as plaintiff, the police feel forced to enter into the transactions by means of subterfuge. Thus, police will play the role of a "trick" in order to trap the prostitute; they will act as though they are addicted in order to trap the drug peddler; they will play the role of a homosexual in the public men's toilets in order to trap the homosexual, and so forth.

The law enforcement agencies have a much easier time when some individual feels wronged, and will present his detailed version of the violation. Many victimless crimes are solved by a partner dissatisfied with the outcome of the illegal behavior. (Police files are full of cases solved by partners in a robbery who were angered by the way in which the money was divided.) The first important dimension then, concerns the possibility of a plaintiff.

The second dimension is almost as critical, and cuts across the first in the manner diagrammed in the accompanying chart. It concerns the arena in which the behavior occurs, namely, whether the circumstances are public or private. The ability of the society to react with sanctions is very dependent upon the visibility of the violation. Exhibitionism is far easier to sanction than is petty theft. Even though both involve a plaintiff, the former is by definition performed in a public arena.40 Law enforcement is most easily achieved, therefore, when there is a public violation and a victim to protest the act. Cell I of the diagram presents some examples of this combination.

It is in Cell I that we can now begin to make a more systematic analysis of the legislation of morality. Laws which affect both the public arena and concern victimization will be most effective in changing the existing moral order. Thus, civil rights legislation is placed in a new light. As we shall see momentarily, it is at the exact opposite pole of discussions about moral legislation on prostitution and drug addiction.

Note that in all four areas represented in the cells, people have strong commitments and feelings. These are all four moral areas, and so it is not simply a question of being able to predict the effectiveness of legislation on the basis of degree of emotional commitment, the substance and nature of values, and the like. An assessment of the possible effectiveness of the law is based here entirely upon such clearly visible and measurable properties as public or private, victim or victimless. The ability of the law to control externally the behavior of consenting homosexuals is minimal. The ability of the law to control externally the behavior of the exhibitionist or the discriminator is maximal. Intermediate between these two extremes are the cases represented in the second and third cells of the diagram. Private violations where there are victims are easier to sanction, and thereby enforce, than public violations where there are no victims to act as plaintiff

It can now be seen that even though the refusal of the right to vote and narcotics use are both in "moral areas," the probable effectiveness of legislation in these moral areas is dramatically different. A black man who is refused the right to register and vote is thus confronted in the public arena. Further, he is victimized and has "recourse" to agencies of law enforcement where he can press his grievances. In this kind of situation, the morality of a social order can be altered by legislation. In more popular ternis, there can be and have been instances of this sense of the legislation of morality. In contrast, the heroin user is no more likely to have his morality legislated than the consumer of alcohol would have been during Prohibition. Both engage in violations of the private sector, and neither case involves a party to the transaction who will act as plaintiff.

The history of narcotics use in the United States sketched earlier has illustrated how the law can shift neutral behavior into that which is strongly overladen with moral condemnation. I have now proposed that the effect of present narcotics legislation, directed as it is to a moral area that is private and "victimless," can not be sufficient to alter the behavior of the drug user in the direction desired by the legislators. What kinds of changes in the behavior of the drug user and his society might be expected from various possible changes in narcotics legislation? So far, there has been an implicit suggestion that more stringent repressive measures cannot produce the results intended. What then, are some of the theoretical and practical considerations that might lead one to propose legal changes; changes that can be expected to alter the moral order even in instances of private and victimless violations? Since it is the narcotics problem that will serve as the specific example of this kind of violation, some background information on the nature of drugs themselves is required before turning to a direct consideration of the larger question just raised.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|