CHAPTER 7 The moral implications of psychic maladjustment in the deviant

| Books - The Legislation of Morality |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER 7 The moral implications of psychic maladjustment in the deviant

THE PRESENT-DAY PHYSIOLOGIST HAS A RATHER EASY TIME a clear separation between physiological illness and moral jucigment. The known fact that a man is suffering from cancer or diabetes does not affect his standing as a responsible, respectable,

or "good" citizen. (It has not always been so. Within the last century, those with certain physical illnesses were believed to be possessed by devils and were shunned and ostracized by "decent" men.)1 The present day psychiatrist or psychologist has a much harder time purging the analysis of certain psychic illnesses of implications of moral judgment. Whether he wants it that way or not, his assessment of certain normal mental adjustments is intricately interwoven into the community's conception of what constitutes a good man. For example, to say that one is unreliable, can not bear to face reality, "retreats into a world of fantasy, gives up, runs away from problems," is perhaps to accurately assess his psychic state and behavior, but it is simultaneously to characterize him in terms that undermine his status as a moral and responsible citizen.2

The reason is simple enough. A "moral" or "good" man in Western society is responsible, independent, respectful of the rights of others, and in the conventional wisdom, able to face the reality the rest of us have come to know.3 At this juncture the intention is not to challenge the professional integrity or accuracy of one who might so judge a specific social deviant, in this case a drug addict. Instead, the goal is to point to a side effect of such a judgment that has its own consequences: that to question the ability of the individual to face reality without a crutch is also to impugn his right to take his place in a community of normal men—men who in their turn see that ability as moral fibre and courage. In Chapter 4, the problem of moral judgment was separated into three levels of analysis: the individual, the community, and the larger culture. Placing the present discussion in that framework, the community consensus of appropriate behavior is the standard by which individual adjustment or maladjustment is set. Whether we are talking about the American who adjusts to his tribe's ritual expectations that he grow grass around his suburban home, shave every day, and support napalm bombing, or whether we speak of the Tchambuli's adjustments to the vicissitudes of his tribe's rituals and hostilities, the psychologist's measuring stick of adjustment must be within the context of the existing social environment. That is necessary because his unit of analysis is the individual, and varying the culture simply changes the substance in the issue of adjustment. Unless or until the psychiatrist and psychologist raise the issue of the moral order at the second or third level, then " . . . a citizen of the Third Reich was well-adjusted in his lack of rebellion and hostility to authority when he did not seek inquisitively and skeptically into why authority purged his neighborhood of the Jews." Yet the moral resistance to admitting to the psychological health in this instance is understandable even in "value-free" scientific circles. Studies of a certain kind of personality (authoritarian) emerged to explain the pathological character of the adjustment.'

But to the extent that the authoritarian personality is capable of an analysis approaching culture-free dimensions, to that extent it has nothing to do per se with adjustment. Adjustments are made to social and cultural conditions and systems. Despite analyses of personality types that successfully leap above the substantive issues, the point remains that a well-adjusted individual is one who does not defy the community consensus of appropriate behavior. It follows that to be well-adjusted is also to be morally acceptable within that community. What has been less well appreciated and explored is its opposite, that to be maladjusted is in this sense to defy consensus and often totter on the perimeters of morality. It is to this problem that attention should now be turned.

We have seen that the dominant interpretation of addiction regards it as a consequence of some defect of the personality. In discussing the "inadequate personality" of the addict, Ausubel quotes the following passage from a Mental Health publication on the inadequate personality:

By the time an individual reaches late adolescence in our culture we can normally expect certain evidences of goal maturation to take place. We can expect him to aspire to a status that he attains through his own efforts rather than to one that he holds merely by virtue of a dependent relationship to his parents. We can expect him to formulate his own goals and reach decisions independently; to be less dependent on parental approval; to be able to postpone immediate pleasure-seeking goals for the sake of advancing long-range objectives; to continue striving despite initial set backs. We can expect him to aspire to realistic goals; to be capable of judging himself his accomplishments, and his prospects with a certain amount of critical ability; to have acquired a sense of moral obligation and responsibility.'

Ausubel then goes on to describe failures of the inadequate personality and tries to tie it in to the behavior of the addict:

The inadequate personality fails to conceive of himself as an independent adult and fails to identify with such normal adult goals as financial independence, stable employment, and the establishment of his own home and family He is passive, dependent, unreliable, and unwilling to postpone immediate gratification of pleasurable impulses. He demonstrates no desire to persevere in the face of environmental difficulties, or to accept responsibilities which he finds distasteful.6

This description treats "immaturity" as a total quality of the personality rather than a selective one which emerges in some situations and not in others. Yet, using the criteria listed above, all of us are mature in some situations and immature in others. Where lies the compelling set of criteria which determine why certain situations are more important than others in indicating whether the personality is immature or inadequate? From the account above, the set of criteria used comes from a single social class's view of appropriate behavior: note the use of "financial independence, stable employment, and the establishment of his own home and family." There is remarkable bias here toward labeling of one social segment of the society as mature and adequate at the expense of another. Sociologists have long since established empirically that the most important determinant of a man's social, financial, and educational status is his father's occupation.' The child from a financially stable home is far more likely to find himself financially independent at age twenty-one than the child from the slums. The same goes for stable employment. But there is an apparent contradiction between the relationship between the "inadequate personality" and drug use if we recall the history of the problem. In the first chapter it was pointed out that the upper and middle classes had more addicts than the lower classes from 1870 to 1904. It was not until the 1920s that the shift in the predominance of those known to be addicted moved from the upper to the lower classes. Is this to be explained by some dramatic transformation in the personalities of the privileged classes in this short decade, and an equally strange transformation in the personality make-up of the lower classes? Did each class inexplicably take on the characterstics of the other in so short a time? Hardly. Rather, the explanation lies more closely to the fact that the social meaning of addiction changed, as did its detection.8

Ausubel is quite correct in his implication that it requires a psychologist to explain why certain persons in a given social group with equal exposure choose or refuse drugs.9 That has never been at issue in this work. What has been heavily questioned and criticized is the conclusion that men have drawn from this, namely, that therefore the psychological interpretation of drug use can be used to provide solutions to the cultural and social problems that emanate from the cultural and social meaning of drug use. The anthropologist or sociologist must raise a different order of question, not of the propensity to addiction of given individuals in certain classes or groups, but of the meaning of addiction in the culture, of why certain classes of persons use drugs more than others, and why differential sanctions are used on these populations. I have suggested and have tried to demonstrate that when the center of society (the middle class is the solid base of social morality in America and the West) engages in a form of behavior, it is safe from strong negatively sanctioned moral judgment. Morphine use in the United States from 1870 to 1900 is an example. But when it is commonly believed that such behavior is the property of those outside the center, it is susceptible to negative moral judgment. With LSD, we are now witnessing a certain manifestation of this. Because it is being more frequently used by university students from the middle classes than by high-school drop-outs from the working classes, LSD use is only attacked as a "dangerous drug," and its use is not treated as an act which qualitatively sets apart the user as a different kind of moral person. One could easily venture the suggestion, however, that had LSD use begun with the less-privileged classes of youth, it would have been categorically treated as a character-defining act. There is something of this in the tendency to castigate the users as bearded hippies, but the fear is now widespread that even the clean-shaven will be tempted.

Background and Qualifiers

There is a hidden danger in attempting to describe and analyze the drug addict who has been apprehended by authorities. Even though one may issue many warnings that the description applies only to known addicts, it is almost inevitable that the cautionary note will be forgotten or repressed in the mounting pressures to explain and understand the general problems of addiction. The warning is worth repeating even for this manuscript, where the term "the addict" is used to signify "the typical addict known to authorities." The following study pertains only to apprehended addicts. It is possible that they are less than one tenth of all addicts." The purpose of this study is not to describe the drug addict, but to realize some greater understanding of the consequences of the moral interpretation of addiction on a select group of addicts. This select group is of particular relevance and intercst because it constitutes an addict population that is the target of a program that tries to work with the commonly believed cause of addiction. The California Rehabilitation Center is explicitly aiming at the psychic problems of the addict. Up to this point, the central thesis has been that the legal shifts, the consequent market conditions, and the social vulnerability of the visible addict in the twentieth century have transformed his problem into a moral one. The moral interpretation of narcotics addiction, it has been argued, is stronger than any other, and greatly influences the psychological and physiological view of the addict. Now we reach a point of direct empirical investigation of this matter to see to what extent the moral versus psychological and physiological views predominate in the treatment of known addicts.

Following is a summary review of what are commonly regarded by the CRC treatment staff as the causes of addiction. Rather than try to obtain a single formal statement of the way in which the CRC treatment staff conceives the causes of narcotic addiction, an examination of the written directives and clarifications of the treatment program will provide a clearer picture. These programs reveal the nature of the staff's conception of the addict in a penetrating manner. Following is an excerpt from a Treatment Model drawn up by one of the staff members, describing what are commonly regarded by the staff as the characteristics of the adult addict:

I. He withdraws from stressful or difficult situations, gives up, retreats, runs away.

2. He feels inadequate, worthless.

3. He can not relate comfortably with authority figures, is fearfully distrusting and hostile.

4. He is very dependent on others.

5. He blames others for his problems.

6. He attempts to manipulate everyone to serve his own ends.

7. He doubts his manhood.

8. He has difficulty in verbally expressing his feelings, especially about himself.

9. He rarely feels or exhibits interest in the welfare of others at the expense of himself.

10. He is fearful of others.

11. He sets up situations that get him punished or rejected.

12. He identifies with delinquent values, delinquent behavior, and rejects those who pursue socially acceptable adjustments and behavior.

I reprint these items of the treatment model not because they are exceptional or unique views of the addict, but because they represent the more typical treatment staff's conception of the problem. It is taken for granted that the addict is a psychologically abnormal individual with a personality disorder:

We try to keep a few psychotic patients on hand if they fit into the program somehow so that they can be used as teaching subjects for both staff and for the "resident" body. For the most part, however, we are dealing with a whole diverse number of personality disorders running the whole gamut of this classification from the schizoid personality to the several categories of sociopathy and passive aggressive personality.'

The following statement is from a staff position paper as represented to a legislator who visited the grounds. Acknowledging that performance in the group is an important part of the judgment of his ability at self-help and coping with his own problems, the position paper went on to say:

Not just by what he does in treatment group . . . A man may look like a real winner, sitting there and talking a lot, but does it follow through on his job? What sort of work traits does he have? Has he availed himself to the educational opportunities in the institution? We try to find out what is happening with the family ties. Is he receiving visits; what are his plans regarding his children? Has he had any disciplinary action? How is his conduct outside the group? How has he been running his life here in the institution? Can he adhere to our institutional regulations?' 2

Not only does the correctional counselor in the living unit write a report on the resident and his conduct in the group sessions and in the dormitory, but written reports come from a variety of sources:

Work supervisors, for example provide reports: a man might get on a work crew—a laboring crew outside, working on ditch-digging, planting lawns, clean-up crew, or something like that. His work supervisor will submit a report on his performance at least quarterly. Too, we follow the normal semester curriculum and we have school grades by the instructor in addition to comments about the man's conduct in the classrooms."

It is made clear to the addict that his life in the institution is under constant surveillance as to his rehabilitation and adjustment. He is not permitted to simply "play the game of therapy" in the group sessions, but he must also demonstrate that this therapeutic aid relates to other aspects of his daily life. The causes of his addiction, as the treatment staff presents the problem to him, are in his psychic disturbance, unnatural and abnormal dependence, and inability to manage the world without drugs. To demonstrate that he is ready for release, he must show evidence to the staff in the many areas of his institutional life that he understands these problems being pointed out to him, that he seriously accepts the analysis, and that he is committed to the task of working out himself the psychic difficulties which afflict him, for which he is responsible, and which he must conquer.

Aims of the Study

The major purpose of the study to be reported here is to ascertain to what extent the moral interpretation of narcotics use exists in a setting where the participants are self-consciously and deliberately committed to a psychological view of addiction. The next purpose is the answer to the question of how the moral interpretation, or lack of it, affects the addict's self-conception, the treatment he receives, and his relationship with the society.

Another purpose of the study is to produce a social profile of the resident addict population at the Rehabilitation Center. The task is to detail such things as the age range among the addicts, ethnic and racial identification, family status, and occupational and sex distributions. After finding those places in the social order where addiction (or apprehension of addicts) is most likely to occur, the next problem is to achieve some explanation of why those particular places in the society should be overrepresented. It may be that further insights into the problem of addiction can be obtained from observing why certain categories are most frequently represented among apprehended addicts. Perhaps a basis of explanation of why particular social categories appear while others do not can be established. From a social profile, patterns and recurrent themes emerge, and the burden of the analysis is to find these patterns and arrange them in a coherent form.

The Sample

The universe for this study was the resident addict population of the California Rehabilitation Center, from early 1964 through the spring of 1965. Because of some continual entries and departures from the institution, there is no static population figure. However, the institution stabilizes around the figure 1,300 for the period of the analysis, with some few score fluctuations over time in both directions. The first study was carried out on a random sample of approximately io per cent, stratified for the male-female distribution." A total of 155 were included in the sample for the purpose of being interviewed in the first segment of the study. There are approximately 1, ioo males in the institution and 200 females. In the sample, there are 103 males and 52 females. The greater proportion of females selected for the study than in the institution was required in order to have enough cases to compare with males. Sex was chosen as an important variable because of the systematically differential treatment accorded male and female addicts both within the institution and on the outside.

The second segment consisted ofa sample of about half of those interviewed. Information was collected from the files on seventy of the interviewed residents. These files were reviewed for the purpose of collecting information that could be used to cross-check some of the responses given in the interview, and also for an independent evaluation of the interviewed residents by the staff. At short periodic intervals, the counselors submit reports and evaluations of the residents. These reports assess progress in the program and indicate the counselor's evaluation of (a) the likelihood of successful rehabilitation and therefore (b) a possible recommendation to the evaluating board for release.

The recommendation is typically honored, and is therefore an important documentary piece for research on the substantive issues in release to the community

Finally, in the third segment there is summary census data collected and presented on the total population of the study, 1,303 residents of the Rehabilitation Center during the last months of 1964. The research report will therefore contain three different populations: (1) the total population of the institution, (2) the ro per cent interview sample, and (3) the cross-check sample whose files were analyzed against the interview material. The assumption is made that the samples are representative of the universe of the study (total resident addict population), but no claim is made about the generalizability of the findings to the total addict population of the United States, or even of California. Quite to the contrary, as has been pointed out earlier, the total addict population across social classes is unknown and unknowable, and the shortcomings of many theories of addiction are traceable to the refusal to acknowledge this critical point. The empirical basis for any theory about addiction is limited to observable behavior. This is truer for social deviance of this kind than for ordinary and typical problems in society (e.g., striving for higher status) since deviants have stronger reasons for concealing themselves.

Methods of Data Collection

THE INTERVIEW

The most important single method of collecting data for this segment of the study was an extensive and intensive interview. All questions were open-ended, although many required only simple responses of one or two words. A cursory review of the schedule reveals that several questions required probes of some depth and considerable skill in eliciting a response with substance. Trained interviewers were therefore necessary, even in the exploratory stages of the research. A serious problem presented itself. Trained interviewers asking residents questions about drug use would clearly be seen by the residents as aligned with the staff. In an earlier discussion, a portrait of the institution suggested how vulnerable residents feel about the staffs judgment and evaluation. The vulnerability is caused by the ambiguous quality of what is meant by psychic integration, coping successfully, and so on, as the resident sees these things existing independent of specific situations in which he finds himself. An inquisitive staff-approved questioner is obviously to be seen as a threat to parole chances, regardless of the objective conditions in the past or the present. The point is simply that the resident can never "know" the specific criteria because they are never given to him as rules (or criteria) that apply across-the-board.

With staff-aligned interviewers ruled out, there was the serious problem of obtaining even remotely reliable data by the interview method, since whoever conducted the interview would be correctly perceived by the residents as staff-appointed and therefore aligned with the staff and its interests and goals. Strategic reasons therefore impelled the research in new directions. Equally important to the strategy problem was the theoretical-methodological issue of how to best establish and maintain rapport with a subject population of men regarded in the society as moral deviants. Part of the answer came from reviewing selected successes of the Synanon program, and part was dictated by traditional sociological knowledge about the behavior of in-groups and reference groups. What success Synanon has enjoyed is based upon the rapport between men and women who are, or have been drug addicts. A basic principle of social exchange is that those in communication have a common point of reference. These are compelling arguments in favor of using addicts themselves as the interviewers. Eight of the residents were selected for training as interviewers. The principal investigator conducted these training sessions, familiarizing the interviewers with the larger aims of the questions and the study and instructing them on how to probe intensively in selected areas. These sessions were invaluable not only for the reason that the interviewers could find out precisely the nature and source of the questions from the person conducting the research, but also because the latter could modify and rephrase questions which the residents (as prospective interviewers) could indicate as ambiguous, or have a different meaning than the one intended. As only one of many such examples, one question asked if the respondent had ever peddled drugs. The resident interviewers pointed out that many who had actually sold drugs to others from time to time might answer this question negatively. The reason is that dope peddling is seen by addicts as a total occupational identity. From this addict point of view, one can no more be said to "have peddled drugs" from occasional sales than one can be said to "have been a fireman" because one has put out fires many times in his life.

Male residents interviewed the males in the sample and females interviewed females. The only exception to this was the series of twenty regular interviews conducted by the principal investigator, who interviewed both sexes.

All questions were presented to respondents with no forced choices. The interviewers were thereby able and were urged to explore interesting and novel directions of a particular response. These explorations were channeled to the extent that they were related to the interests and orientation of the research project as discussed in the training sessions.

One of the pitfalls of this kind of research is the assumption that the respondent and the interviewer mean the same thing when using the same term. For example, one question asks whether the respondent feels morally inferior to nonaddicts. Before beginning to answer the question, the resident might ask what the interviewer means by "morally inferior." The interviewer's response W9S to explicitly deflect the question and instead explore what the resident himself conceived as moral. The reason for this rests in the fact that the subjective experience of moral inferiority can not be tapped unless the respondent is allowed to express his own interpretation of the terms of the question.

In addition, the interviewer must guard against subtle variations in meaning that are not even questioned by the respondent, and therefore never raised as issues for discussion. It is hardly possible to ask every respondent what he means specifically by particular phrases. However, as Aaron Cicourel has suggested, there are some adequate techniques that can be used to minimize the difficulties of multiple meanings." Following Cicourel's suggestion, the principal investigator conducted an additional ten separate interviews not included in the sample proper.

The purpose of these interviews was to clarify some of the problems of communication between interviewer and interviewee that are otherwise ignored.

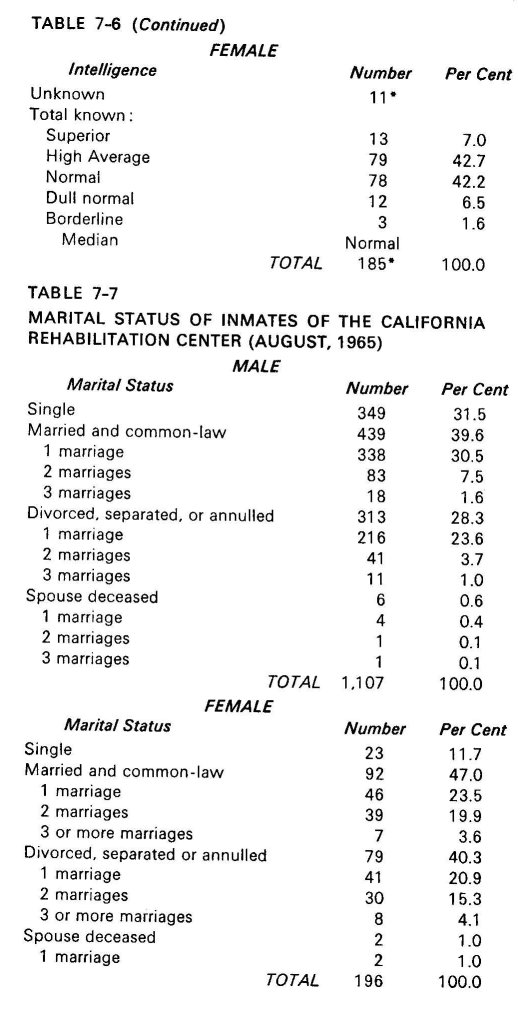

Characteristics of Total Population: 1,303

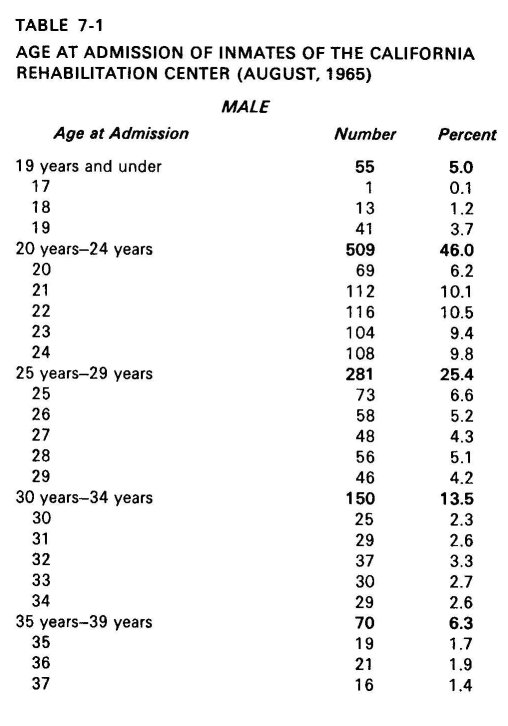

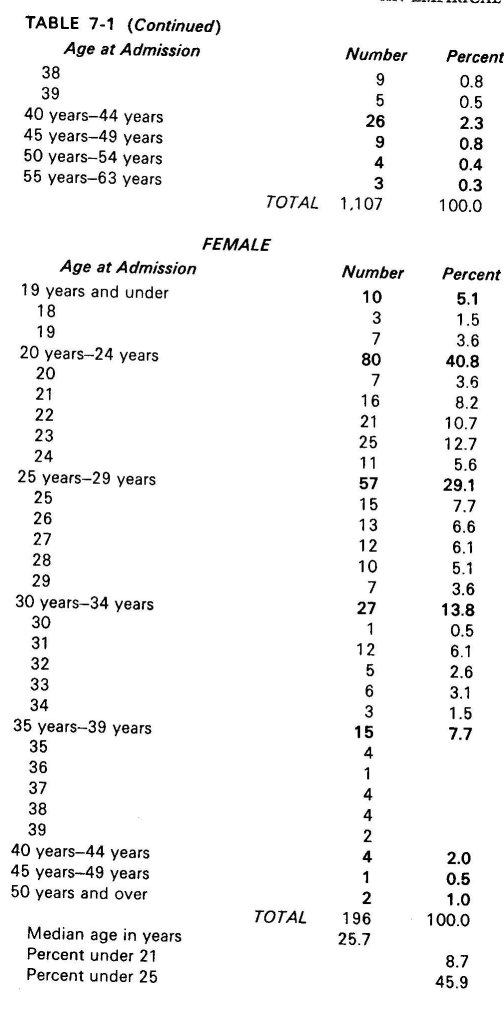

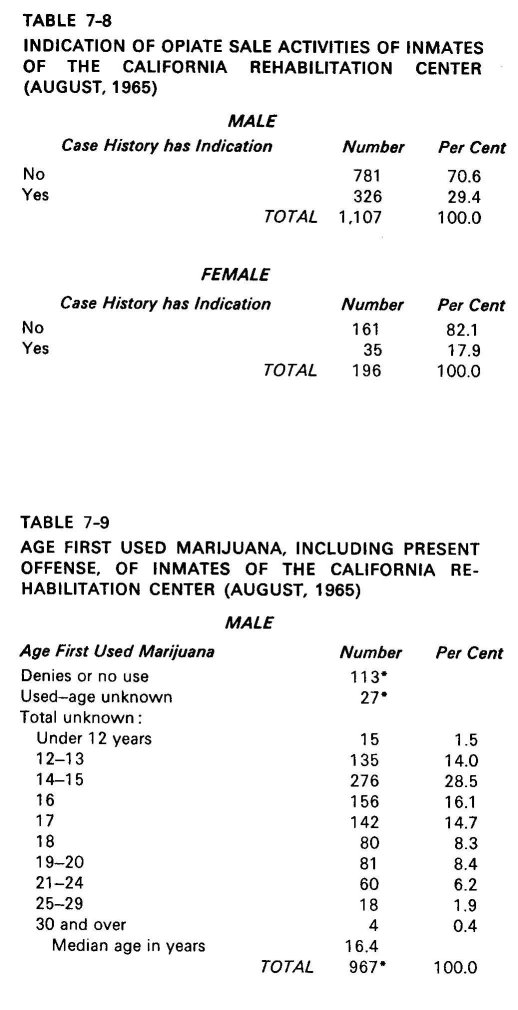

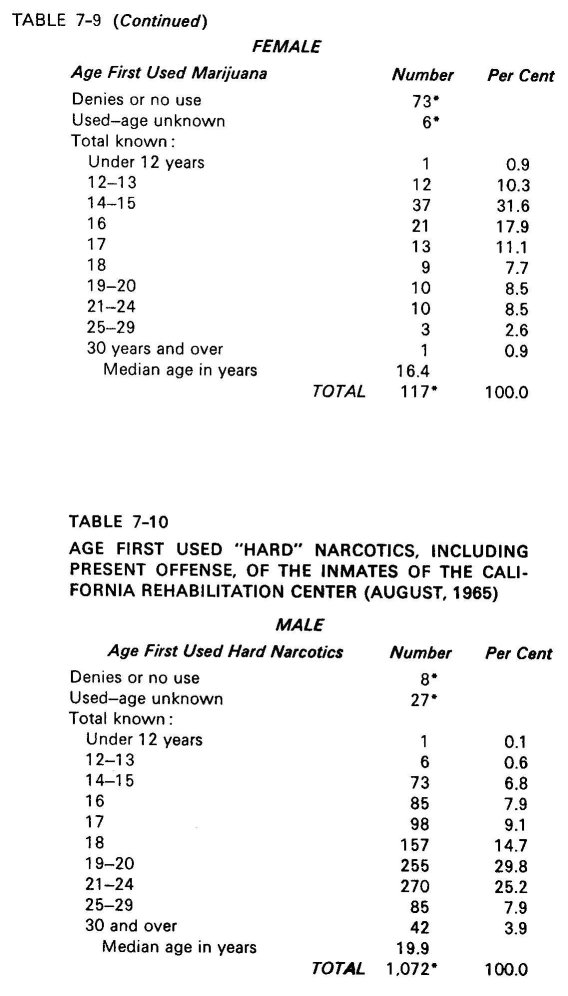

The ratio of males to females in the institution is almost 6 to 1. It is also a very young population, with more than 75 per cent being under the age of thirty. (Table 7-I) These two characteristics are similar to most other reports on the qualities of the known addict since about the year 1920. (As was pointed out in the first chapter, before that time most known addicts were middle-aged and female.) The same pattern holds for ethnic, geographic, and occupational variables. The tables show that the ethnic minorities not only have disproportionately high numbers of the addicts at CRC, but that they actually are a numerical majority of the inmates.

The most dramatic of this finding is the large number of Mexican-Americans apprehended as addicts. Among the males, half are Mexican-American. (Table 7-2) Negroes appear in relation to their number in the population. Thus, in comparison to other studies of narcotics use, they are unexpectedly under-represented."

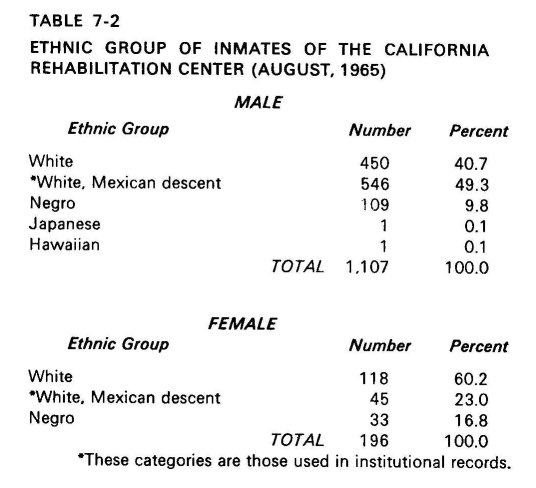

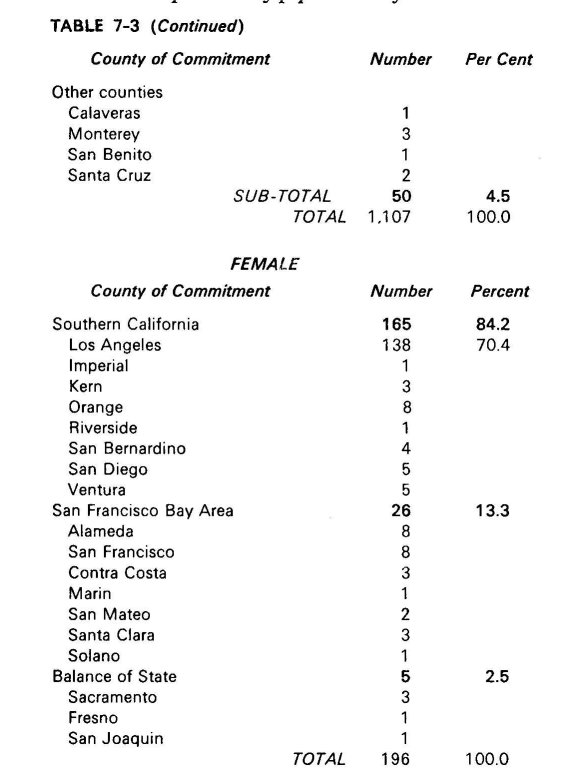

The city is the breeding ground for almost all known addicts, and in California, one city is far and away the leader. Two of every three persons in CRC come from the county of Los Angeles. (Table 7-3)

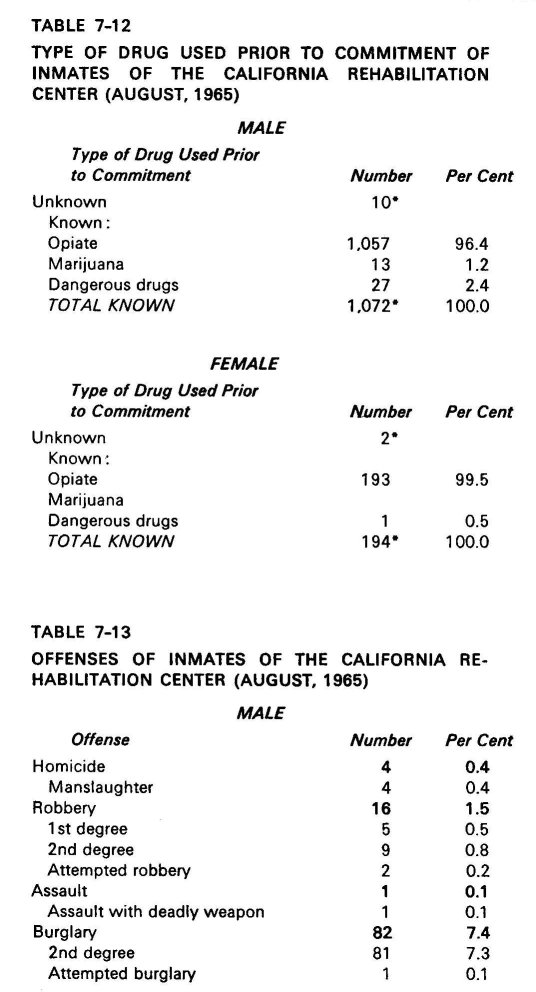

These findings then bear out or reflect the generally known facts about apprehended addicts: that the problem primarily exists among the young, among males, in the cities, and among the ethnic and racial minorities. It is also true that the inmates at the rehabilitation center are predominantly working and lower class. In fact, white-collar or middle-class occupations for the inmate or the inmate's family are notable exceptions. More than 90 per cent of the inmates could be identified with either working- or lower-class occupations, or a history of no employment." When this is contrasted with the fact that the 1960 census for the United States revealed that over so per cent of the country's labor force was white-collar, one can get a sense of the gross overrepresentation of the working classes among the apprehended addicts.

Miller has suggested that the lower-class environment is one in which the conditions for "getting in trouble" are very great." Whether he is right or not it is certainly true that there is something in the lower-class situation that makes its members more susceptible to arrest, prosecution, and conviction than the middle classes.

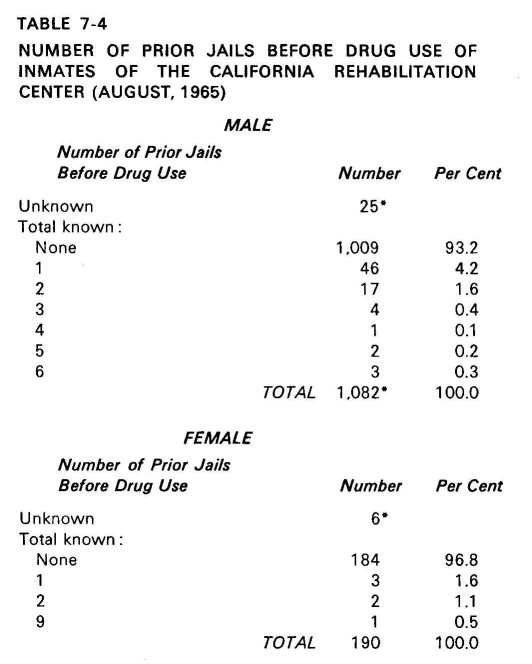

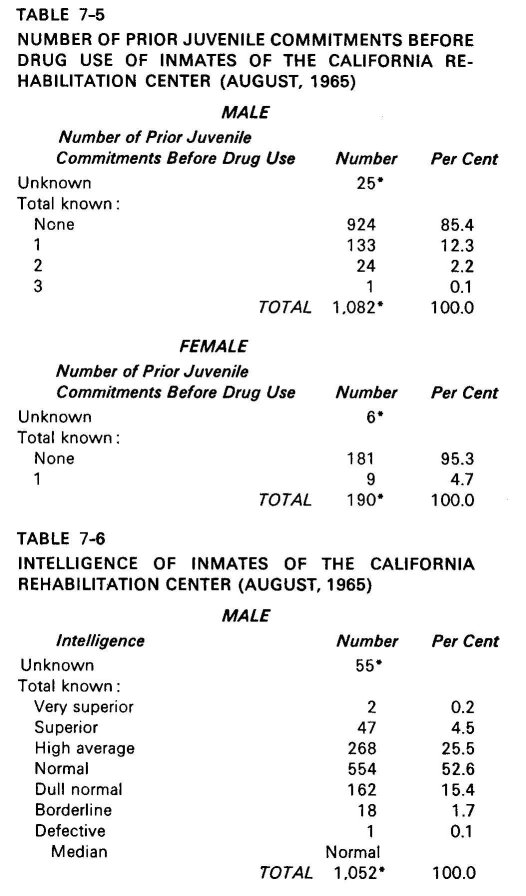

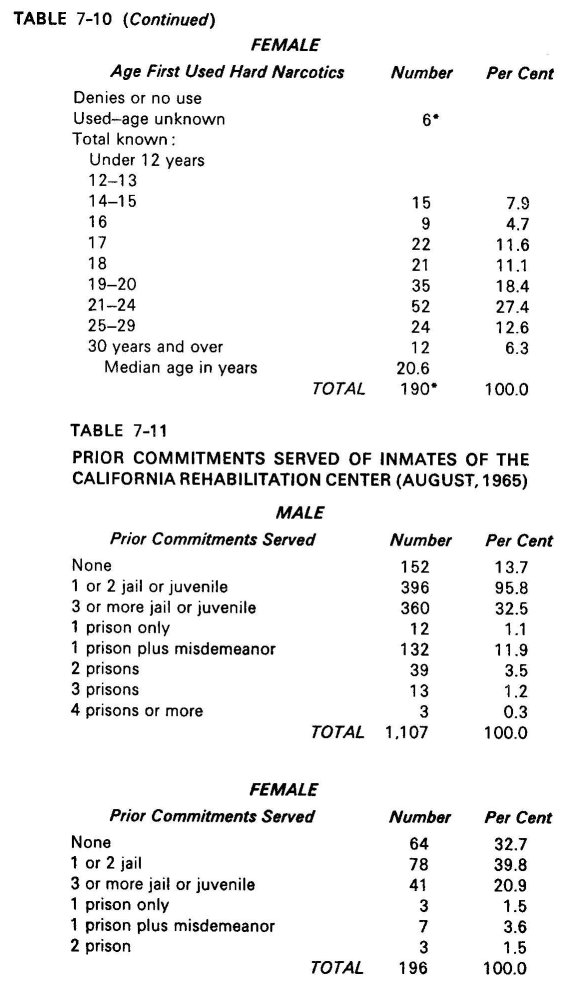

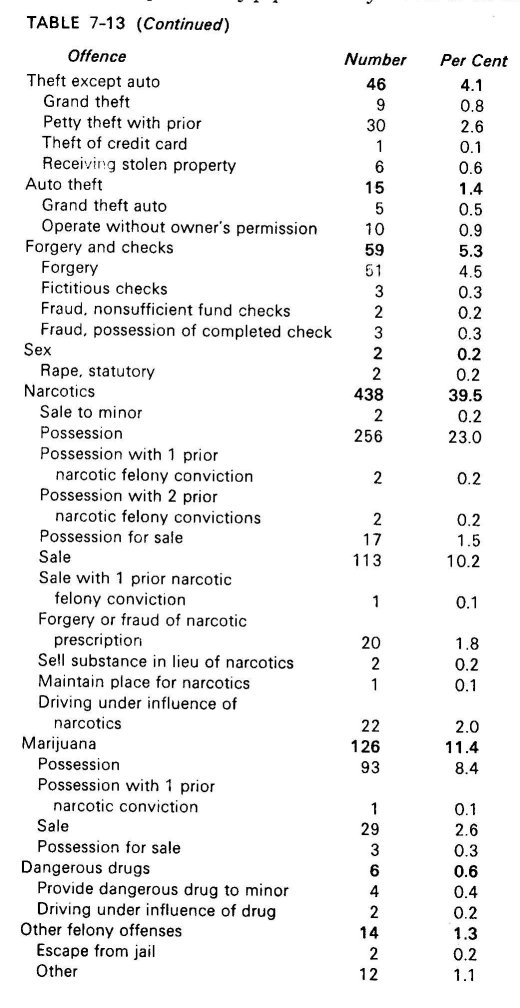

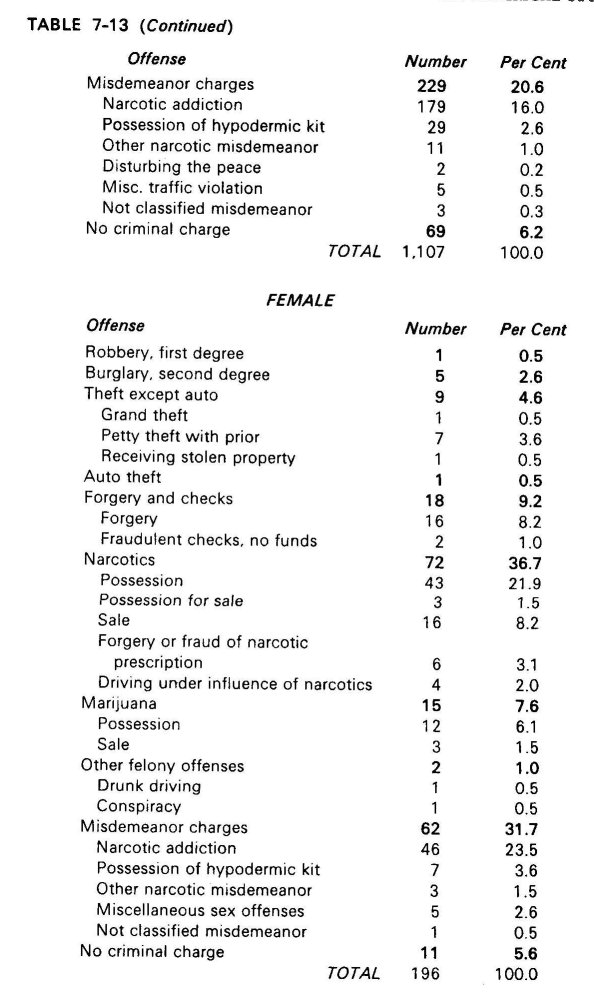

One of the most important findings from the study of the total population is that 93 per cent of the male inmates at CRC had no jail history prior to offenses for their use of drugs. (See Table 7-4) This figure refutes the often heard claim that the drug addict population is a criminal population before it turns to drugs. This argument, from the arsenal of the Federal Narcotics Bureau, would have it believed that drug use is simply another form of criminal activity engaged in by persons who have already been established as criminals by their other violations of the law. In fact, if we look even at the history of prior juvenile commitments of the CRC inmates, 85 per cent reveal no juvenile record. (See Table 7-5)

Findings from Interview Study

Whereas no claim is made for the generalizability of these findings to the addict population outside the institution, the results from the interview should be representative of the total addict population at CRC.

Findings from an interview study such as this are subject to two important and recurrent criticisms: (1) How does one know if recall is accurate? and (2) even if the memory of the respondent is complete and correct, can we take his statements as anything more than the superficial, self-conscious realizations of his condition and personality? It should be stated at the outset that neither of these questions need be raised in order to develop an explanation of the patterns of social relationships that exist. For example, when we know empirically that people at the top of the social world say that the world is a just place and people at the bottom say that it is not, there is no need to pose the question as to whether people "really feel that way" in order to explain and predict how such statements vary with social position. Further, when we can observe that the well-to-do in any society tend to vote more heavily to conserve the existing social order, explanations do not stand or fall upon the ultimate reality of whether the voters "know" they are acting in terms of their self-interests, either short- or long-range.

As for challenging the recall ability of a set of respondents, that problem is most critical when there is reason to believe some motive for systematically telling lies. Where a set of say one hundred respondents show a pattern of recalled events, there is a built-in check unless (a) there is room to suspect collusion, or (b) the question probes into an area known to be socially sensitive or taboo. For example, questions about abortion, sexual failures, or informing to the police touch areas where one can expect systematic falsification. However, recall ability of the number of rooms in the home of a friend, and so on, is at the opposite extreme.

In these interviews with addicts, both kinds of questions occur. An attempt has been made to avoid giving the impression of the ultimate reality of responses to certain questions even though they may be of use in other kinds of explanations. On the other hand, ability to remember whether one's first experience with marijuana was "alone or in a group situation" was treated as having face validity.

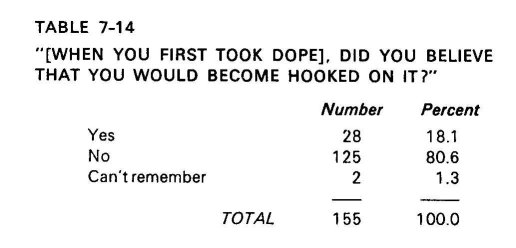

THE PATH TO ADDICTION

In an earlier discussion, some issues were raised concerning how it is possible for knowledgeable men to become addicted to heroin. The outsider finds it incredible that any individual in possession of all his faculties would knowingly take the path to addiction. It was suggested that part of the explanation is to be found in the idea of the indestructibility of the self " The prospective addict sees himself as an exception to the pattern of addiction around him. Notice that over 80 per cent of the respondents said that, when they took a narcotic for the first time, they were sure that they would not become hooked (Table 7-14). Of the few who said that they did believe that they would become addicted, only a fraction maintained this position upon probing. It usually developed that even though they realized the possibility of becoming addicted, they refused to believe it would actually happen to them.

The naivete or lack of information of the beginner user about the danger or risks in drugs should be cast aside as an explanation for how one starts with drugs. In this group, virtually all claim to have known teat heroin was addicting when they first used it.

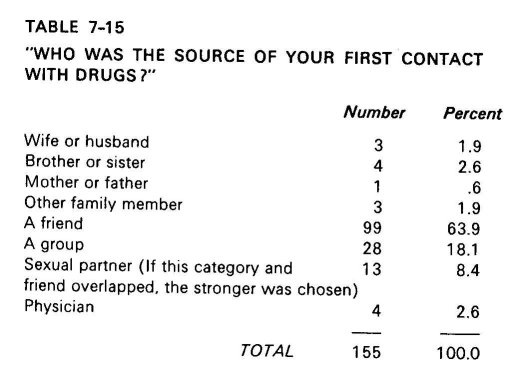

The first source of contact with the drug was usually a friend. (Table 7-15) Contrary to popular mythology, the professional dope-pusher (one who himself does not use but deals only for the profit) almost never contacts the novice and entices him for his first trial. Instead, a friend, who is himself an occasional user but not an addict, invites him to a gathering where the drug is available. Those who are themselves addicted possess a strong moral code that acts as a barrier against initiating novices. Infrequently the code is broken, but the situation is one where stress is great due to the impending onset of withdrawal.

In the circles where the CRC inmate grew up, marijuana was easily available. Any of a number of his acquaintances might take him to a party where pot was being smoked, and any of a number of these might be an occasional heroin user. It is a serious mistake however, to jump to the conclusion that marijuana leads to heroin.20 The only point here is simply that the widespread use of the drugs in a person's normal everyday environment means that he will come into contact with it in a normal and everyday manner. It is not the dejected, depressed, and withdrawn moment that can be identified, nor does it appear to be true that there is some critical turning point in the decision to experiment with drugs the first time. For these addicts, the available evidence suggest nothing pathological in the way of a moth-flame compulsion. Quite to the contrary, the addict seems to be drawn into a normal set of social relations and normal kinds of social behavior when he experiences the drug for the first time.

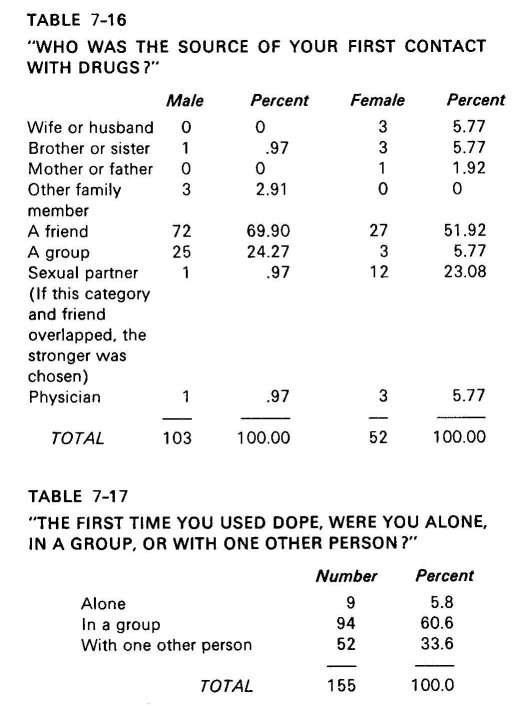

For the female, the case is a bit different. She is more likely to be pulled into drug use because of her close emotional attachment to a single other individual who uses heavily, or is addicted. The attachment may be to a lover, to a husband, or sometimes to a homosexual lover. The pull to drug use seems to be through some single other person. (Compare tables 7-15, 7-16, and 7-17.)

In the whole sample, only eight cases were cited where a family member drew one into narcotics use; and in seven of the eight cases, the person drawn in was a female. It is equally striking to notice how females differ from males when we look at the sexual partner as the initiator to the drug experience. While almost one fourth of the females started taking drugs with a sexual partner, less than one male in a hundred began in this way. Much of the explanation lies in the power relationship between males and females in the society in general, since women are more dependent upon the financial need to hold the support of men with whatever means they can devise.

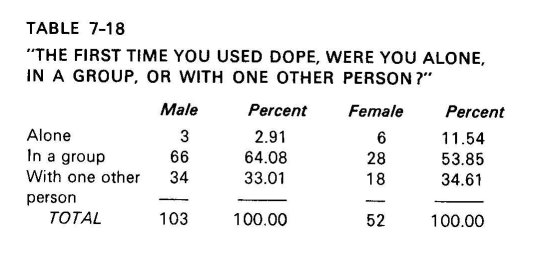

It should be carefully noted that neither males nor females report that their first experience was when they were alone. Indeed, the first experience is usually in a group situation for both, rather than a single other party (Table 7-18).

These findings suggest that the social dimension of the early experimentation with narcotics is more than a simple desire to conform to a deviant subculture or to rebel against middle-class authority and morality. It seems instead to be a configuration of events that unravel in a normal sequence. It achieves its insidious anti-bourgeois, anti-authority character from the response that later comes from the authorities, agencies, and institutions committed to a different moral-legal view of drugs. Explanations of the rebellious nature of the drug user are very much like explanations after the fact in prison riots, wildcat strikes, and spontaneous student unrest. The most trivial and unpredictable of events may set off a prison riot.

Once the riot starts, however, the rioters start writing up a list of legitimate grievances with the institution, a list which authorities and newspapers then treat as the cause of the original disturbance. In fact, every grievance on that list has usually been going on for decades, often in a more insufferable way than at the point of the riot. But the list is used as the basis of explaining why the riot occurred. The same thing happened with the Berkeley student revolt in 1964. The immediate source of the student rebellion was the response to specific and individual injustices to an arbitrarily selected group of students." Yet, when the analysts finished explaining what had happened, one would have thought that the list of grievances drawn up by the students was the real source." In fact, Berkeley students (as all other American student bodies) had up to that time and have since that time, lived complacently, obediently, and peacefully under the very conditions described in that list as the cause of the revolts. Why then the rebellion at that moment?

There is a parallel to the discussions of the rebelliousness and curiosity of the drug user. He lived peacefully for decades under conditions similar in form to those now described as the indicators of personal inadequacy.23 When the law shifted the legal conditions, the addict's list of grievances, liberally supplemented by the experts, was suddenly treated as the explanation of his addiction.

Marijuana is usually the first narcotic that the individual tries, but it is by no means the only path to heroin usage. Unlike many American college students, the CRC inmates are very likely to have been exposed to both marijuana and heroin traffic. They could more easily make the choice. Thus, those instances where they did not go on to heroin use are all the more significant in questioning the popularly cited relationship between the two drugs. The ethnic and racial differences in patterns of heroin versus marijuana use are quite instructive for a discussion of the path to addiction. First of all, there has been a dramatic upsurge in the incidence of marijuana usage and heroin addiction in the Mexican-American communities of Los Angeles since 1950. Marijuana especially has recently become very much a part of the life of the lower and working-class Mexican-American adolescent's world. The precise reasons for this development are subject to explanation at several levels. In simple traffic terms, one clear explanation is the large flow of marijuana into the Mexican subculture from across the Mexican border. It is a long border that is only a few hours away. The communal ties and old primary associations facilitate distribution. In this light it is interesting to note that, for the modal case, Mexican-Americans in CRC began using marijuana at about age fourteen or fifteen. The most frequent age at which they began with heroin was eighteen. Blacks begin both marijuana and heroin usage much later. Most Negroes reported that their first experience with marijuana was between the ages of eighteen and twenty, while heroin contact did not begin for most until the middle twenties. One popular explanation for this is that the bulk of the black community in Southern California has been more recently settled. Because these youths got there much later in their lives, it follows that they begin everything a bit later, including deviance. That is only partially true for this sample, since a large proportion of the Negroes had resided in the California county from which they were apprehended prior to their tenth birthday. Another current explanation is a modified frustration-withdrawal hypothesis. Blacks continually confront situations in which they are the objects of discrimination. For some, this builds up into frustration and hostility. For some, this turns into resignation, alienation or withdrawal. Narcotics provide the withdrawal. This sequence takes time, however, and that is why black youth tends to start with drugs much later.

One part of this interpretation fits very well into what is known about ethnic and minority conditions. First, the black community is not a subculture in the same sense as the Mexican-American. There is no separate language, no distinctive kinship structure, and fewer customs and traditions which set the Negro apart from the dominant group. The Mexican-American can more easily achieve a distinctive cultural identity precisely because he has a separate language, a familial lineage system that differs from the dominant society, and distinctive traditions. There is, however, one more important factor explaining the differences in the path to addiction by the two groups. The two minorities have a different way of looking at the world of objects and of men. If it were simply a matter of dress and costume and of tradition, or a matter of the way one holds a knife, effects a dialect, or carries a stride, men could readily communicate and blend cultures. It is far more important that these things which are different in their outward appearances often carry with them a way of conceiving of things, for example, a different view of the sexes and their places, and a conflicting posture toward issues treated as the basis for moral crises.

For the Mexican-American, extended kinship is an essential fact of existence. For the native white American, and for the black American especially, extended kinship is often problematic, confusing, and conflicting. To simply assert this sheds only a glimmer of light on the finding about Negroes and whites drawing family members into addiction upon occasion, while Mexican-Americans rarely if ever do. However, if one is to understand that finding and others like it in the largerc ontext of varying cultural paths to addiction, the nature and role of kinship must be examined. The nuclear family is the primary kinship unit in the United States, as it is in every culture where technology has undermined large communal family life as an important economic base. In a society that is so specialized that one member "goes to work" to provide for everyone in the household, the household had better have five or six members, not twenty-five or thirty. So the older people of Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United States, can all be heard to present the common complaint of being cut off from the nuclear family unit. Mexican-Americans in this country, especially the Southwest, are far more likely to retain an identity and ties with a traditional culture that does not see the nuclear family unit as a separate one. Contrast both of these situations with that of the Negro, whose slave past purged him not only of an extended lineal kinship, but rendered problematic the nuclear family itself. For two and a half centuries, the tradition of the Negro in the United States was to deny the nuclear unit on the simple expedient that he could control neither offspring nor spouse."

In the single area of kinship structure, things are quite different for Blacks and Mexican-Americans in ways that vary even to the manner in which they conceive of filial relationships. All of this has bearing on the relative degree to which the Mexican-Americans have a distinctive subculture. The family unit and its relative importance in the culture is but one area where documentation is possible. This cultural distinctiveness helps to account for a variety of otherwise confusing differences that can be found between Blacks and Mexican-Americans in the addict population. For example, it is possible to make sense of the fact that though both are minorities, Negroes wait longer (until age eighteen to twenty) to begin narcotics use. At least from the base point of the frustration-withdrawal hypothesis cited earlier, the cultural context adds new meaning. When Negroes experience discrimination, they have a less coherent cultural base to relate to, but return again and again to the dominant culture to meet more of the same. They may delay the withdrawal and alienation until they have experienced a good deal more frustration. Interviews with black addicts at CRC provided some support for this notion, but interpretation should be cautious because of variable regional conditions.

The moral interpretation of narcotic use and narcotic addiction is the primary focus of this research, as has been elaborated in the earlier sections. How this moral view varies with ethnic and age groups should be instructive in finding out the effects of select cultural experiences on social patterns of addiction. Those groups of addicts who are most likely to confront a strong moral reaction from the society should be those whose addiction is most abhorrent to the dominant society. Youthful middle-class whites scandalize their immediate community, the juvenile authorities, and the courts by their narcotics usage much more so than early-adult working-class Blacks. It follows that the strength and intensity of the moral reaction to the former will be stronger. Although the three qualities of age, class, and ethnicity have been combined for the purpose of the example above, each operates independently. The moralistic reaction to an adolescent's drug usage is predictably stronger than reaction toward an adult; the reaction to drug usage by the middle class toward one of their class is stronger than the corresponding reaction in the working or lower classes, and so forth. Men come to expect different behavior from other men who have different positions in the society. The banker's son who is a known user violates expectations far more strongly than the factory worker's son, or the son of a mother on public relief. The former is a violation which produces the response of indignant action. Accordingly, it is predictable that addicts from a middle-class background, addicts who are white, and those who were addicted at a relatively young age should express the strongest feelings about how morally different they are from others in the society.

The CRC addicts who are convinced of their own general moral inferiority reign themselves to a more peaceful relationship with the world. They make little effort to rehabilitate, even in the terms of satisfying the requirements of institutional commitment. This is reflected in the evaluations and judgments filed on individual resident addicts. A content analysis of these files revealed that those respondents who judge themselves most harshly in moral terms tended to be less successful in the eyes of the treatment person making the assessment of their progress in the institution. It is no accident that the staff made generally more positive prognoses of those inmates who would not say that the staff felt morally superior to addicts. There is some difficulty here in deciding which comes first, the prognosis or the refusal to cast the staff in these terms. The interesting empirical problem is the extent to which these judgments vary along socially patterned lines.

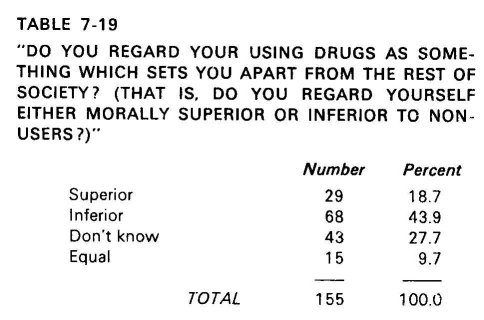

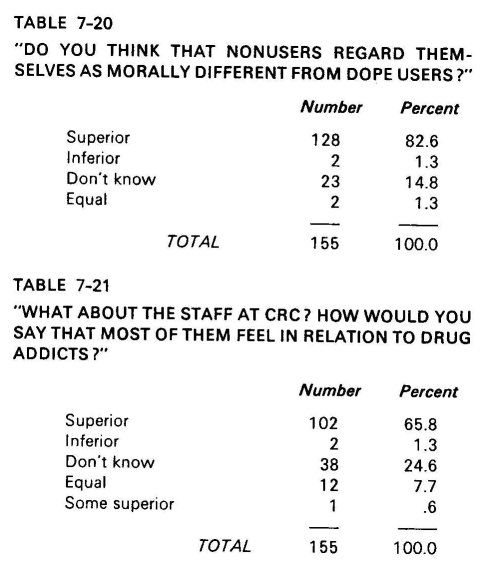

Each respondent was asked if he felt that his use of drugs was something that set him apart morally from the rest of society. (Table 7-19) Two thirds could say that they felt that it did. Four out of every five addicts could assert that nonusers regard themselves as morally superior to narcotics users. (Table 7-20) In light of the self-conscious attempt by the staff at the Rehabilitation Center to recast the problem in therapeutic terms, it must be noted that the residents impute to them an almost equal measure of feelings of moral superiority. (Table 7-21)

That is, despite the fact that the treatment staff uses the language of psychology and psychiatry in dealing 'with the addicts, the latter still feel that the primary way they are being looked upon is moral. Some of the residents who see this as inevitable reasoned that it is a consequence of the staff's greater power position in the institution. That is not necessarily true, since in an educational institution, students rarely (except facetiously) impute to the administrators or the faculty, who have more power, convictions of moral superiority. Or in an institutional setting such as a modern corporation, the lower line position of an individual carries with it no firmly predictable feelings of morals difference. While it is true that the army and the church, as institutions, are heavily laden with moral censure aligned to position, this is very much a function of the substantive properties of these institutions.

Soldiers, priests, and treatment staff come to a world that has been preinterpreted for them in very moralistic terms.

Most of the addicts at CRC report that they feel morally inferior to nonaddicts. From probing in the interviews, there is evidence that they believe this to be a constitutional element of their character, not subject to change either by treatment or their own will. For example, many residents indicated that they wanted to respond better to the program, but that the situation they found themselves in was hopeless because of the different world view of addicts and nonaddicts. A quality of semi-bitter despondency was apparent among them. Many felt that the power in the world is held by moralists who make arbitrary decisions about the morality of others. Nonetheless, these same respondents granted legitimacy to derogatory characterizations of addicts. An unexpected theme that persisted through many of the interviews was the anger, resentment, and even indignation which resident addicts displayed toward other addicts as addicts. Sociologists have come to expect fervent anti-Semitism from Jews located in certain social positions, and they have come to expect caustic anti-Black expressions from certain Negroes. It is still surprising, however, to hear a man express contempt toward a whole group of men incarcerated in the institution with him ostensibly for the same kinds of offenses against the society.

Sometimes this hostility toward other addicts integrates the pejorative and the psychological. Some said, for example, that "There ain't nothin' worse than a goddamn junkie. He's immature, always tryin' to rationalize for what he does, always tryin' to blame others. He can't take the world, so he takes the coward's way out." Just a shade underneath this analytic layer is contempt: "I've known hundreds of hop-heads in my life and I know, they're no good to themselves or to anyone else; they're the most selfish people in the world."

When men come to believe that they are morally different from other members of their society, and when they believe that the others agree with this and are justified, their deviant behavior and its sustenance over time is both predictable and explainable. The primary issues in the treatment and rehabilitation of such individuals concern the ability to breach the large gap of moral interpretation between addicts and nonaddicts. It is a mistake of some magnitude to assume that addicts as deviants can be changed as an independent population. The reaction to addiction in the society is interwoven with the addict's moral conception of himself So long as he retains the conception of his own moral difference, he has a justification and explanation for his own morally different behavior. The ability to change that conception can not be separated from the ability to change the moral reaction which produced, and produces, that conception.

There may be a few individual cases of successful return to society in a large population of addicts, just as there are individual successes in a program such as that of Synanon. But the gross problem in the society is not mitigated by a few individual successes. If we speak in terms of the typical case, any rehabilitation program of social deviants is doomed to fail in its own terms by its own criteria ("rehabilitation") so long as the larger society treats rehabilitation as passage between two moral categories. The typical addict at CRC sees himself in terms of moral inferiority. He also sees other addicts as inferior in kind and character to the rest of the population. His perceptions are simply reflections and mirror-images of the dominant attitudes toward addiction in this country for the last three decades. In sum, rehabilitation between two moral categories can not succeed by directing attempts at change only toward the category of the "morally inferior." Even if a treatment staff was completely free of such feelings, and even if every ex-addict left an institution personally and morally committed to change his behavior (both of which are empirically untrue), the moral interpretation of addiction in this society is so strong that return to the old communal ties is predictable for the typical addict.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|