6 Status Politics and Middle-Class Protest

| Books - Symbolic Crusade |

Drug Abuse

6 Status Politics and Middle-Class Protest

The polarization of the middle classes into abstainers and moderate drinkers is part of a wider process of cultural change in which traditional values of the old middle class are under attack by new components of the middle stratum. In this process of change, Temperance is coming to take on new symbolic properties as a vehicle of status protest. In the current arena of American cultural conflicts a potential affinity exists between the Temperance movement and other forces whose political identities take shape from status issues which symbolize the revival of old middle-class values.

For much of the nineteenth century and in the early twentieth the conflicts between cultures over consumption patterns and the uses of leisure took place in an institutional context of classes, churches, regions, and ethnic identities. Most of the conflicts between pro-Temperance and anti-Temperance forces which we have described in the earlier chapters were of this kind: Protestant versus Catholic, "native" versus "ethnic," rural versus urban, middle class versus lower and upper class. In recent decades, the development of a more homogeneous and nationalized society, coupled with extensive social mobility, has diminished the close relation between institutional and cultural commitment. As we have seen in the previous chapter, the conflicts about drinking within the Protestant churches and churchgoing groups today are as great as those between Protestant and non-Protestant or between the religious and the secular. The terms "fundamentalism" and "modernism," which we shall use to characterize two different sets of values in present-day American life, are applicable to groups at the same class level in the society, and within the same institutions. The two middle-class groups are no longer poles apart. They live in the same cities or towns, share the same neighborhoods, belong to the same churches, and even send their children to the same schools and universities.

THE FUNDAMENTALIST RESPONSE TO MASS SOCIETY

In the past two or three decades cultural polarities in American life have been deeply influenced by new sources of ideas, techniques of operation, and associational commitments beyond the level of the local community. These have resulted in a split within communities dividing the society into two major cultural groups. One group reasserts older, traditional values which have been identified with the old middle class of the nineteenth century. The other group identifies the modern as the normative order to be followed. It sees its model in the values of new middle classes of salaried professionals, employed managers, and skilled workers in the basic industries.

The cultural fundamentalist is the defender of tradition. Although he is identified with rural doctrines, he is found in both city and country. The fundamentalist is attuned to the traditional patterns as they are transmitted within family, neighborhood, and local organizations. His stance is inward, toward his immediate environment. The cultural modernist looks outward, to the media of mass communications, the national organizations, the colleges and universities, and the influences which originate outside of the local community. Each sees the other as a contrast. The modernist reveres the future and change as good. The fundamentalist reveres the past and sees change as damaging and upsetting.

Sources of Cultural Conflict

In recent years a number of writers have pointed out that a major change in American values has made the cultural truths of the nineteenth century less certain and less honored in the twentieth. In the now classic statement of this view, David Riesman refers to "the characterological struggle" between inner-directed and other-directed personality types. These persons find their values in opposition. Feeling themselves as losers in the historical process, the champions of the older forms are deeply upset: "Inner-directed types, for instance, in the urban environment may be forced into resentment or rebellion. . . . I think that there are millions of inner-directed Americans who reject the values that emanate from the growing dominance of the other-directed types." 1

The sources of these changes are many and their analysis beyond the scope of this work. They represent, however, two major axes of conflict in American life: the struggle between local and mass society and the struggle between a production-oriented and a consumption-oriented culture.

The conflict between local and mass society is that of divergent sources of power and influence. Where the locality, the immediate community, is the source, the orientation is local. Where the nation, the region, and the metropolis are sources, the orientation is toward mass society. As American society is increasingly dominated by national rather than local structures, the mass society assumes great significance as the source of cultural ideas while local power and status are undermined. The local banker manages a branch of a larger system whose basic framework is determined by policies in Washington and in the major cities. The local grocery store competes with the chain outlet of a national firm. The local teacher is torn between the values disseminated by her professional, national codes and those of the community in which she teaches and may have been raised.2 The local social lion looks like "small potatoes" when measured against the national status system.

These national and extralocal structures carry to the local community the content of a national, homogeneous culture. The media of mass communications, the professionally trained experts, and the migrant middle class carry the culture of the mass society into all communities. "The new society is a mass society precisely in the sense that the mass of the population has become incorporated into society." The older, traditional patterns are enunciated by the status claimants within the local structure; the newer patterns are carried by those who are oriented toward the mass society.

A significant aspect of the conflict in cultures represented in the fundamentalist-modernist struggle is in the area of production and consumption. The shifts in drinking patterns described in the last chapter are manifestations of general changes in American attitudes toward work, play, and impulse gratification. The culture of the mass society is increasingly a culture of compulsive consumption, of how to spend and enjoy, rather than a culture of compulsive production, of how to work and achieve.1 Vidich and Bensman, in a study of small-town life, found a sharp distinction between the life styles of the farmers and businessmen as contrasted to the life styles of professionals and skilled workers: "The greatest shift in the dimensions of class is an increasing emphasis on stylized consumption and social activities as a substitute for economic mobility. . . the underlying secular trend indicates a shift from production to consumption values in the community." 5

The gradual transition from a society of small enterprisers, of whom many were farmers, to one of employees of large-scale organizations has placed less importance on the direction of life through an ethics of work. Great increases in productivity and technological progress have introduced leisure time on a large scale. The result is a decreased emphasis in national culture on the importance of restriction, saving, and the core of work-oriented values represented in the Protestant ethic and the values of the Temperance ethic.

In their study of a small Michigan city, Gregory Stone and William Form have produced a clear picture of the cleavages within middle-class life to which we are referring. With the location of national corporations in Vansburg, a large number of managerial personnel and salaried professionals became residents of the city. These people rejected the existing symbols of status and styles of life held by the upper middle-class people who had been living in Vansburg. They did not attempt to emulate the patterns of the established social elites. Instead they utilized the habits and customs of the sophisticated metropolitan resident. They developed their own communal forms and challenged the previous status of the "old" elites:

They appeared publicly in casual sport clothes, exploited images of "bigness" in their conversations with local business men, retired late and slept late. They "took over" the clubs and associations. . . . The Country Club, for example, has undergone a complete alteration of character. Once the scene of relatively staid dinners, polite drinking and occasional dignified balls, the Country Club is now the setting for the "businessman's lunch," intimate drinking, and frequent parties where the former standards of moral propriety are often somewhat relaxed for the evening. Most "old families" have let their membership lapse.e

Stone and Form found that the matter of drinking was the major symbol by which these two contestants in a status contest were differentiated, by themselves and by other residents of the city. The split in the middle class was characterized by interviewees as one between "drinkers and nondrinkers." Unlike our descriptions of these terms in late nineteenth-century Temperance accounts, this was seen as a horizontal cleavage, within the middle class, and not a vertical one, between middle and lower orders. It is also noteworthy that the examples of areas in which these two groups were in conflict were largely those of leisure-time behavior, with the "cosmopolitans" rejecting the restrictions on impulse release so central in the life styles of the "old families."

The effect of the cosmopolitan ethic of mass society is to debunk the older values of the middle classes in which a production orientation to life was bolstered by religious institutions. "There is the moral emancipation of 'Society,' with its partial permeation of the upper middle class, the adoption of manners and folkways not in keeping with various traditional canons of respectability."

The Fundamentalist Reaction

These processes are more than upsetting to the person who, from his period of early socialization, has internalized traditional values and has made these the core of his claim to status and respectability. The fundamentalist reaction is a reassertion of those values and a ,condemnation of the modern values as illegitimate and unentitled to cultural domination.

We have spoken of the fundamentalist culture as an aspect of social structure, locating it in the old middle classes. Actually we are dealing with a cultural group, united by their common commitment to a set of values and norms. While the shared set of commitments may be historically associated with the old middle classes, at the present point in history the fundamentalist may be found in other structural contexts as well. Social change, because it does not involve patterns of socialization and internalization, often takes place more rapidly than does cultural change. During the past 40 years America has witnessed a great decline in percentage of farmers and rural non–farm dwellers. Migration has brought into urban places and into industrial occupations large segments of the society that have been socialized in different contexts. The cultural values laid down in early youth and passed onto children via familial training may contradict the structural position. This means that we should not assume that cultural categories, which we are here using in a framework of status hierarchies, are equivalent to structural categories, which we are here using in a framework of economic class. The term "old middle class" has both a structural and a cultural connotation. We are asserting that "old middle class" dies harder than the "old middle classes."

There are two aspects to the fundamentalist reaction, one defensive and the other aggressive. After Repeal both are common themes in Temperance materials. There is a revivalistic tone and a preoccupation with the regeneration of values in many areas—family life, child training, swearing, religion, and many others. In all these areas American life is depicted as having degenerated from an earlier position of virtue. There is a call for restoration of "those homely virtues of truth, honesty, recognition of authority, morality and respect for age." 8

The defensive side of fundamentalism expresses a sense of estrangement from the dominant values and the belief that a return to the dominant values of the past, based on religion, economic morality, and familial authority, will solve social problems. One respondent remarked that conditions in the United States are similar to those at the time of the fall of Rome, that "there is a complete moral and spiritual degradation. The corruption and the spending and the drinking are the worst of it . . . . We need a regeneration."

Increasing secularism and the assumed decline in evangelical, fundamentalist religion is suggested as the cause of everything from juvenile delinquency to the threat of nuclear war. "Deepening the spiritual life of the nation" is seen as an essential prerequisite to national economic, moral, and political success. "Religion, in terms of weekly church-going, sincerity, and grace before meals, is the best form of juvenile protection." 9

The detrimental consequences of the decline in middle-class dominance are expressed in this way by attention to the symbols connected with that dominance. Religious ritual, thrift, parental discipline, and individualism are contrasted with a contemporary society that applauds secular rationality, indulgence, equalitarian family relations, and economic dependence upon public agencies. Any change in the direction of the "old-fashioned virtues" enhances the social status of the Temperance followers. It is the decline in the general cultural standards which they bemoan.

The aggressive aspect of the fundamentalist reaction is its hostility to whatever smacks of the modern. If the values which manifested old middle-class superiority are undergoing decline, the responsibility for this loss of prestige is located in the modernist. As the fundamentalist has developed his institutional expectations around symbols which now appear less prestigeful, "aggression has turned toward symbols of the rationalizing and emancipated areas which are felt to be 'subversive' of the values."0

The central target of this hostility is the content of the mass society as contrasted with the local community. Sophistication, science, psychiatry, modern child rearing, contemporary educational methods are among the complex of patterns and institutions which are attacked as immoral and responsible for present-day ills. Cultural values that emanate from the national institutions of school, entertainment media, and even the major churches are depicted as sources for the decay in the status of the old middle class:

The battle on the side of right used to be a shout; now it is a whisper. . . . No evil walks alone. Drinking is not the only wrong accepted by a society that would have been shocked at it yesterday. Sex crimes are common. .. . Honesty is no longer enthroned. . . . There is a tendency to tear down everything that the past has struggled to build. Personal hygiene no sooner attains the goal of common decency than some publicity seeker cries out against too frequent washing of hands. The college graduate shies away from the use of correct English for fear of being classed with highbrows. The world is waiting for a return to some of the old virtues.11

Temperance as Fundamentalist Symbol

Moderate drinking itself symbolizes the loss of status incurred by followers of fundamentalist belief. Drinking is a matter of great significance in the fundamentalist complex of values. Because abstinence is a major fundamentalist virtue the increased acceptance of consumption-oriented styles of life in the United States constitutes a distinct threat to the old middle-class culture. It diminishes the socializing agencies committed to production-centered values and minimizes the institutional pressures supporting abstinence.

As the new middle class has developed cultural patterns distinctive to it and opposed to nineteenth-century values, the place of impulse gratification in work and leisure has been redefined. Self-control, reserve, industriousness, and abstemiousness are replaced as virtues by demands for relaxation, tolerance, and moderate indulgence. Not one's ability to produce but one's ability to function as an appropriate consumer is the mark of prestige.

The shift has a decided bearing on the status connotations of drinking. In the nineteenth century there was much fear that if the restrictions on impulsive action were even slightly lowered, the individual would go to the extremes of evil and social ruin. Temperance propaganda was often shocking in the detailed accounts of excessive actions brought about by one fatal sip. If there is a philosophy of leisure today it is not evoked by the fear of temptations but by the problem of capacity for enjoyment. The fear is one of inability to have fun, to relax, and to play. Liquor can become a social facilitator in a culture which is afraid that people are unable to "let loose" sufficiently.

In the recent past there has been an increased tendency to attempt by drinking to reduce constraint sufficiently so that we can have fun. . . . From having dreaded impulses and worrying about whether conscience was adequate to cope with them, we have come around to finding conscience a nuisance and worrying about the adequacy of our impulses. . . . While gratification of forbidden impulses traditionally aroused guilt, failure to have fun currently occasions lowered self-esteem.12

This description of American culture today is all too real to the Temperance adherent. He agrees with Miss Wolfenstein's characterization of the current cultural atmosphere but he feels apart from it, estranged and a defender of the past. The rise of moderate drinking is a sign of this change and of the status loss which he has suffered. In reasserting the legitimacy of total abstinence he is also affirming the validity of the larger fundamentalist patterns.

POLITICAL FUNDAMENTALISM AND TEMPERANCE

The tenets of cultural fundamentalism have political corollaries which can lead to conservative, right-wing positions in American politics. The political significance of fundamentalism lies in the tendency of the fundamentalist reaction to produce a political perspective which converts issues of class politics into issues of status politics and which interjects issues of status into politics. In this section we are interested in the relation between the Temperance movement and the general orientation of the fundamentalist toward politics. We have already examined the Prohibition issue as a case of status politics. If the political effects of the fundamentalist reaction stem from the same sense of estrangement and search for status recoupment as has the Temperance issue, we can anticipate a close alliance between the Temperance movement and the forces of conservative and right-wing politics.

Political Fundamentalism and Status Politics

American attitudes toward politics often fluctuate between a cynical, compromising spirit and a hortatory moralism. As a "broker of interests" the politician is exhorted to handle all issues as matters of bargaining, adjusting one set of interests and values to another with little concern for anything but a solution acceptable to the parties involved. The moralizer in politics,13 however, cannot adopt such an air of efficient search for compromise. For him, political issues are tests of virtue and vice in which those on the opposite side are immoral. Politics is a matter of possible sin and of hoped-for salvation. When issues are structured in moral terms they become tests of status. In the context of cultural conflicts, the moralization of issues places the prestige of each status-bearing group at stake.

A political issue becomes one of status when its tangible, instrumental consequences are subordinated to its significance for the conferral of prestige. With specific reference to the fundamentalist-modernist schism in culture, political issues which derive importance from their use as symbols of this conflict function in the orbit of status politics. The argument is less over the effect of the proposed measures on concrete actions than it is over the question of whose culture is to be granted legitimacy by the public action of government.

The issue of debt management is illustrative of one issue in American politics which has strong overtones of status conflict. As is true of many issues, there are those who stand to gain or lose materially by increased governmental deficit spending. The trauma induced in bankers and creditors by the fear of inflation is clearly understandable as a reflection of economic interests. The similar trauma induced in the professional, the businessman, the farmer, or the white-collar worker is not understandable on the same basis. Economists have pointed out the complexity of the problem of national debt and they do not see increasing debt as dangerous per se." The reaction of the noncreditor can be understood as a response to the moral connotations of debt as evil and spending as vice. If the society is to applaud action which violates the norms of his style of life, then the abstemious, thrifty, saving businessman, professional, farmer, or white-collar worker has received a blow to his sense of esteem. He has found that his society does not support his claim to prestige based on his adherence to such norms. Whether he has personally suffered or gained by inflation, the changed attitude of public officials toward debt represents a status deprivation, and the old middle-class citizen responds with fear and hostility.15

In another form, the fundamentalist sees specific issues as conflicts between one cultural commitment and another. The fluoridation movement is a good example of how an issue of health has been turned into one of conflict between fundamentalists and modernists. Opponents of fluoridation reject the symbols of science, welfare, and governmental officialdom and assert the values of religion, natural environment, and individual action. "The imagery associated with a negative vote on fluoridation suggests that it was in large measure a revolt against authority, scientific as well as political." 16 The issue of health was subordinated to one of local versus mass culture, of one status group against another.

Conservatism and Temperance

Since the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment there has been an underlying tone of political conservatism expressed on many issues in the Temperance movement. Although the issues of liquor legislation and education have been paramount, the materials of the WCTU and of the Prohibition Party display concern for more general political questions. They show a tendency to uphold fundamentalist ideologies by asserting conservative political positions which emphasize status elements.

The emphasis on style of political action is the dominant note in the criticism of the New Deal which was often voiced by Ida B. Wise Smith, the WCTU president during the 1930's. She left little doubt that she abhorred the legislative activities of the New Deal. The logic of her position was couched in terms critical of departures from past principle. In 1934, for example, she devoted one section of her annual address to warnings against departures from the Constitution. In the same year the WCTU passed a resolution deploring the legislative grants of power to the executive. In 1936 she referred to the evils that have come upon us in recent years, not in reference to Repeal, but as a general trend in the society. She called for preservation of the Constitution and election of persons who "will utterly rout the social evils that have come upon us in recent years." 17 While not naming names, Smith implied that Roosevelt must be defeated.

The affront of the New Deal and of Roosevelt to the Temperance fundamentalist was only in part a result of the Repeal Amendment. In fact there is very little specific criticism of the Democrats as the authors of Repeal in the post-Repeal years. It is the morality of their general policies that is under fire. One of Smith's frequent complaints was that the President and other public leaders did not show enough religious commitment, especially by public acts of prayer: ". . . in past years when great emergencies arose, leaders like Washington and Lincoln called upon the people by proclamation to set apart a day for fasting and prayer and repentence in hope that the nation would come to that condition of mind and heart wherein God heals the land. There is no indication that this is so in the thinking of the nation now." 18

The antipathy of the WCTU leaders to the New Deal was, of course, not necessarily shared by all fundamentalists, nor do we attribute it to all Temperance followers or WCTU members." Nevertheless it was sufficiently widespread so that the president of the organization could express it openly in national meetings and in resolutions. It represents the growing separation between the liberal politics of assimilative reform and the Temperance movement. During the same period of the 1930's the Social Gospel went through a resurgence in American life which left little impression on the policies of the Temperance groups.

For the Temperance movement the fundamentalist reaction in politics has been heightened by two facts. First, Repeal was a major setback, reinforcing the alienation of the fundamentalist from domination and enhancing his sense of status decline. Second, the fact of Prohibition reinforced the identity of the Temperance adherent with the 1920's and Herbert Hoover. The WCTU all but ignored the Depression as a significant part of the experience of the 1930's. They did not address themselves to it. In a sense, the fact of the Depression severely damaged the prestige of the old order, the shining light of Herbert Hoover, and the claims of Prohibition to have brought about prosperity.

The election of 1928 was a profoundly significant one for Temperance. In that election the movement supported Hoover and also openly allied itself with an anti-alien and anti-Catholic tradition. Not only did it repulse a number of liberal Temperance followers, such as William Allen White, but it strengthened the identification of the movement with the Republican Party and against the Northern Democrats. It was a decidedly bitter election, with much shifting of traditional party lines. For the first time in its history the WCTU openly endorsed a presidential candidate. The Prohibition Party openly opposed one major party candidate, favored another, and almost retired from the ballot entirely.2° When Repeal occurred in 1933 it was with an administration whose pro-immigrant and urban character had been defeated in 1928 but rose to power in 1932. What could seem secure in such a topsy-turvy world? The symbols in which the abstainer had heavily invested were repudiated.

In assessing the policies of political figures in the 1930's, the Temperance follower looked for actions which might restore his sense of dominance. Emphasis on character and morality is a reflection of this. The political platforms of the Prohibition Party reveal this same concern with the decline in morality and plea for actions which bring about "spiritual awakening." 21 The assessment of economic issues carries with it the same recourse to the fundamentalist spirit. It sees new and unfamiliar actions as immoral. They disturb the certainty of belief in established, traditional solutions to national problems. In 1925 the editor of a conservative Baptist journal answered a writer who doubted the truth of Resurrection by saying: "It is like saying that the bank in which you have put all the money you have in the world is insolvent." 22 Of course, in 1931 and 1932 the banks did prove to be insolvent.

Rightist Reaction in the Postwar Period

Writing in 1952, in the journal of the WCTU, Mrs. D. L. Colvin, then national President of the organization, recounted her experiences as an observer at the Republican convention. There was need for a new party, she maintained, "which would bring together the level-headed Southerners and Northerners, with a middle of the road attitude, neither leftist nor extreme rightist but loyal Americans with the desire to do what is best for America and the world without destroying America while doing it." 23 Colvin was expressing two themes which appear in varying degree in the organizational literature of the Temperance movement during the 1950's. One theme is the alienation from major parties on general political issues, not solely Temperance. The other is the rightist political philosophy which is manifest in her implicit criticism of American foreign policy. At the time she wrote, political forces which attempted to use General Douglas MacArthur as a rallying point were the major political elements fitting her description of a new political party for the disaffected. To some extent, however, the Prohibitionists were moving in the same direction.

Colvin used the same argument in her efforts to persuade her followers to vote the Prohibition Party ticket in the 1952 elections. The Prohibitionists, she said, could appeal to voters dissatisfied with both parties and who see little between them on foreign policy matters. "Both claim to be conservative but both support New Deal policies." 24 The Union Signal reprinted an editorial from another journal which made even plainer the criticism of the Truman government on grounds of "coddling the Communists, against the 'left-wing' conduct of our domestic economy. . . against the tragedy and imbecility of war in Korea . . . the general incompetence of our leadership in our national affairs." 25

As an organizational commitment the conservatism of the WCTU has remained diffuse, more a matter of tone than of definitive actions. A persistent antiwelfare orientation has emerged, but this too is more diffuse than concerted. In the area of general disaffection from current political positions, the WCTU has remained neutral, although expressing a political fundamentalism.

The Prohibition Party, on the other hand, has moved toward an open appeal to right-wing elements of both major parties. They appear to be attempting to convert the Prohibition Party to one of extreme right-wing protest. They have accordingly emphasized the multiple issues of the party and the right-wing conservative position on a wide number of issues. The National Prohibitionist, organ of the party, is less concerned with liquor questions than it is with political issues instrumentally unconnected with Temperance, such as Communism, foreign policy, fluoridation, education, and governmental economy.

Reading the platforms of the Prohibition Party over the past 90 years one can see. how Populism has turned into a neo-Populism which often contradicts its original instrumental tenets. For example, the early platforms of the party, as we have seen, were Populist in calling for government to aid the farmer in his struggles with big business and with finance. This theme continues during the early twentieth century. During the Depression it is again a basis for an attack on the banks and a demand for inflationary policies. By the 1950's, however, the actions of government in past eras have begun to take on hallowed characteristics. Political disaffection is less oriented toward increasing demands for governmental action than toward decrease. If there is a sense of not being part of the governing groups, then it is better to curtail governmental actions. If inflation as a major policy is threatening to the sense of moral fitness, and hence of prestige, of its adherents, then the opposite policy becomes virtuous. During the 1950's the Prohibitionists have built an appeal based on distrust of government, calling for decentralization, states' rights, limited taxation, and an end to restraints on free enterprise. "We believe that good government ought not to attempt to do for people what they can do for themselves." "We deplore the current trend toward development of a socialistic state." 26

This orientation occurs in the context of status politics in two ways. First, it appeals to people to whom the symbol of Prohibition is evocative of cultural fundamentalism. Second, it expresses a demand for a government which will "restore" past conditions. It is this theme of regeneration and restoration which unites the Populism of the past with the neo-Populism of today.

THE EXTREMIST RESPONSE: LIMITED AND EXPRESSED

The concept of a "radical right" has assumed considerable usage both in social science and popular writing in recent years. 27 It expresses the phenomenon of radicalism as an orientation toward institutions and groups which may be identified with opposite sides of political struggles. It is possible to be radically anti-Communist, laissez-faire, pronationalist, and on a number of other issues to be identified with conservative positions in such a fashion as to be extremist and in opposition to the status quo. The right-wing extremist attacks the political institutions themselves, impugns the motives of officials, and repudiates the norms of political tolerance between opponents. The demands he makes for change are radical in that they represent sweeping alterations. Right-wing radicalism utilizes the fundamentalist culture as a source of its values but seeks to defend it as a holy war against enemies. "Its hostility is incompatible with that freedom from intense emotion which pluralistic politics needs for its prosperity . . . [the extremist] is worlds apart from the compromising moderates." 28

In American politics right-wing extremists have demonstrated a search for status equality in attacks on the symbols of mass society and cultural groups whom they perceive as having become socially and politically dominant. As a consequence, the contents of rightist radicalism have been nativistic, jingoistic, and xenophobic. The extremist has sought to increase the value of his membership in native American culture by strident nationalism. He has sought to condemn his enemies by associating them with national enemies. Through it all, the extremist has expressed a deep mistrust of official, public institutions of church, government, communications, and school. It is in this latter sense that right-wing radicalism has been neo-Populist in its ideology.

Within the Temperance movement, the right-wing extremist has appeared as one possible direction in which the movement might have gone and in which some aspects of it have been going. In part a harsh anti-alienism and nationalism exist as a diffuse strain in some parts of the movement, unorganized and unchanneled. In part, an open rightist radicalism exists in the shape of Prohibition Party doctrine.

The Decreasing Attack on the Alien

Protestant-Catholic conflict was a basic part of the Prohibition movement and of the issues during the Dry decade. While different wings of the movement represented assimilative and coercive attitudes toward immigration, the alien was seen as an opponent of Temperance and of middle-class life styles. The status position that the Temperance adherent was defending had its origins in his identity as an ethnic and religious member. As the relevant cultural polarities in American life have come to overlap ethnic and religious diversities, anti-alienism has decreased its centrality in American politics, although it has by no means disappeared."

A comparison of the role of Temperance forces in the 1928 and 1960 presidential elections is instructive in this regard. Alfred E. Smith was anathema to the Temperance forces and they committed themselves openly and intensely in the campaign to elect Hoover. Even here there were distinct differences within the movement. The WCTU, in their characteristically less coercive orientation, muted their aggressive tones. They supported Hoover and campaigned against Smith, but they presented a more restrained public face, less extremist in tone and less openly anti-Catholic and anti-alien than did the Anti-Saloon League and the Methodist Board of Temperance, Prohibition, and Public Morals. The prominent Prohibitionist leader, Methodist Bishop James Cannon, led the mobilization of Protestants against Smith as a holy war to maintain the social supremacy of the native American: "Governor Smith wants the Italians, the Sicilians, the Poles and the Russian Jews. That kind has given us a stomachache. We have been unable to assimilate such people in our national life. . . . He wants the kind of dirty people that you find today on the sidewalks of New York." 30

The election of 1960 re-created the Protestant-Catholic issue on the plane of presidential politics. Despite the existence of a large amount of anti-Catholic sentiment generated in the campaign, the Temperance movement remained aloof from both the campaign and the nativist expressions which were current in many Protestant circles. Neither the WCTU nor the National Temperance League endorsed either candidate. In their journal The American Issue, the Temperance League, offshoot of the former Anti-Saloon League, ignored the campaign entirely. The WCTU was less indifferent but they took no position, despite some diffuse anti-Kennedy sentiment.

The attitude of the Prohibition Party is even more instructive. In 1928 they broke with their long-standing doctrinal position that the differences between the two parties were insignificant. They were on the ballot but had also endorsed Hoover, promised not to rim in areas where he might be politically hurt by loss of Prohibitionist votes, and were pledged to withdraw entirely if this seemed necessary to Hoover's victory.31 In 1960, while expressing considerable right-wing extremism, they did not serve as a vehicle of intensive anti-Catholic sentiment. While there appears to have been support for a pro-Nixon stand by the Prohibitionists, it was not dominant. The position of the party, as expressed by Earl Dodge, Editor of The National Prohibitionist, was that the Republicans were no more defenders of church-state separation than were the Democrats, that Kennedy would probably be less subservient to Catholic church influence on school aid questions than would Nixon, and that both candidates were socialistic."

It appears that neither major party is sufficiently associated with Temperance or with cultural fundamentalism to have made the 1960 election as crucial for the movement as the 1928 one had been. This is a reflection of the alienation of the Temperance adherent from the major organized parties.

It is certainly not true that anti-Catholic and anti-alien sentiments have disappeared from the Temperance movement. They can be found in the literature of the movement in isolated passages" and expressed by some followers in congressional hearings .3 4 The organized and patterned open expression is not as significant as it was in the earlier periods of Prohibitionist zeal. This facet of right-wing radicalism is less a part of Temperance doctrine than it has been in the past.

Nationalism and the Cultural Struggle

The opposite is evident in issues that touch upon foreign affairs, militarism, and domestic Communism. Here there has been drift in the direction of nationalist sentiments which express a defense of fundamentalist culture.

The Prohibition Party has shown an explicitly right-wing radical doctrine on a number of issues. They have expressed a fear that American policy is operated by groups and by criteria whose cultural commitments give no recognition to the fundamentalism the Temperance adherent stands for. An intense mistrust of science, of government, and of education runs through the pages of The National Prohibitionist. In February, 1961, for example, Rollin Severance, Prohibition Party candidate for U.S. Senator from Michigan, wrote an article opposing repeal of the Connally Amendment. In it he attacked the United Nations as having been organized by "Alger Hiss, Harry Dexter White and Russia's Molotov." He warned that if the Connally Amendment were repealed, the UN would have the power to ship Americans anywhere in the world to where "they" (the UN) wanted. He opposed the Genocide Treaty and warned about "China-betraying judges like Jessup." In the course of the article he also attacked fluoridationists and the mental health programs."

This coupling of mental health, the UN, the American foreign policy, and fluoridation is also contained in the platform of the party, a document marked by its extreme defense of laissez-faire economics, states' rights, and opposition to governmental action in welfare areas. The general orientation of the party is expressed in a letter to The Indianapolis Star by Earl Dodge, Chairman of the Prohibition Party: "We oppose Federal aid to education, support right-to-work laws, oppose socialistic policies such as are being practiced right now in our government and call for an end to foreign aid to Communist nations and other dictatorships. We are the only party on the Indiana ballot this year which stands for conservatism."33

The anti-Communism of the radical right appears both in their condemnation of foreign policy and in their orientation to domestic groups. This is an attitude which identifies sources of dominance in American life as distrustful and alien. Insofar as the groups that hold power in America cannot be identified with cultural fundamentalism, with the orientations of the old middle class, their actions are responded to by a sense of fear and loss. In antifluoridadon and mental health opposition they express their suspicion of the role of science and the carriers of its culture. The attack of the Prohibition Party on federal aid makes the point of cultural struggle quite clear. They assert that the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare employs "one-third of the top echelon of Communist conspirators in the United States." Hence the objection to placing ‘`our children's education under the control of the most extreme radicals in our government."37

Within the WCTU there has been a less extremist trend in the same direction, toward a more hostile and critical posture with respect to international alliances. Both the WCTU and the Prohibition Party had been antimilitaristic, in the periods before and after World War II. Both organizations had supported American participation in the League of Nations in 1919 and after. In the 1930's both manifested the neo-Populist isolationism represented in attacks on military profiteers and the investigations of the munitions industries, which they demanded. They supported disarmament conferences and the passage of the Ludlow-Ware bill to provide referenda on declarations of war. In the 1930's the WCTU in Kansas fought against the introduction of ROTC into Topeka high schools and after World War II both organizations opposed peacetime conscription and also the adoption of universal military training.38

In the 1950's there is a more pronounced antipathy to symbols associated with antimilitarism and with international cooperation. The UN is especially a target for criticism. It is the style of the organization, as a vehicle of nonfundamentalist culture, which attracts the negative response in the WCTU. While the UN was at first supported, the resolutions of the 1950's became more negative and qualified. The secular and cosmopolitan image of the UN was singled out as the aspect which caused the Temperance adherent most concern. Mrs. D. L. Colvin devoted a portion of several annual addresses to criticism of the UN for failure to observe prayer in opening their meetings or to recognize God or the Bible as an aid in their deliberations. "The Prince of Peace, through whom peace can and will come to the world, is absolutely ignored. King Alcohol is on the throne at Lake Success." 39 This is a clear admission of the way in which the association of the UN with styles of life that oppose the old middle-class symbols are experienced as threatening.

In similar vein, the opposition to conscription has been muted and softened. A leading WCTU official during recent years was much opposed to universal military training and was much more negative toward the UN: "The United Nations, now there's something. . . . I believe in supporting it when it's an instrument for peace, but not when it's an instrument for appeasement and dishonor."

This remains, however, a most diffuse undertone of rightist sentiment. The Communist issue has been virtually ignored in WCTU materials, either as an issue of importance per se or as tied to Temperance issues. The WCTU presents the appearance of an organization which adheres to cultural fundamentalism but can hardly be said to have embraced the radical right, as the Prohibition Party has. While political issues are perceived in status terms, in terms of cultural loyalties and oppositions, extremist sentiment has not been given organizational expression.

THE DILEMMA OF THE TEMPERANCE MOVEMENT

A sense of isolation and rejection hangs over the Temperance movement like a persistent black cloud. It forms the atmosphere in which indignation and bitterness are nurtured. Whether to resolve that sense of rejection or to utilize it as a source of organized zeal is the basic dilemma of the movement.

Decline and Isolation

Despite the shifts in the prestige of drinking and the end of Temperance political dominance, total abstainers are still a large segment of the American population. In fact, "estimates of the proportion of drinkers suggest a levelling-off since World War IC" In 1945, 33 per cent of the adults surveyed by Gallup were abstainers. This slowly increased during the annual surveys to 45 per cent by 1958 and fell again by 1960. Nevertheless we can estimate, from the Gallup Poll and other studies, that at least one-third of the adult population do not drink. This has remained fairly constant during the past 15 years, as manifested by the similarity of this finding in studies taken by different observers at different times in the past two decades.4' Whatever may have been the fate of Prohibition and the Temperance movement, total abstinence is a widely followed custom. The same studies also show that abstinence has declined among college-educated groups. This substantiates the decline in the prestige value of abstinence norms which we have found reflected in WCTU materials. Abstinence today is most frequent in the lower middle- and lower-class Protestant of the more evangelical and sectarian denominations. The Episcopalian and the Lutheran were seldom supporters. The Presbyterian, the Congregationalist, and the Methodist are less firm and the Baptist is wavering. It is among the Nazarene, the Church of God, the Jehovah's Witness and the less institutionalized and influential churches that Temperance seems to be growing most rapidly today.

Local option results support a conclusion similar to that derived from survey results. There has been little loss of support for Dry measures during the past 20 years. The "hard core" of political following appears to have remained remarkably stable. The existent pattern of liquor control in the United States has been largely effected by local option elections at the county level. As stated above (Chapter 5), as a result of state and local Prohibition in 1939, 18.3 per cent of the American population lived in locally Dry areas. In 1959 this percentage had only declined to 14.7 per cent, despite the repeal of state Prohibition in Kansas and Oklahoma.42 Dry strength had increased in 16 states while Wet strength had increased in 15 states.

Despite intense local activity in elections, there has been remarkably little change during the past decade.48 During the period 1947-59 there were 12,114 local elections held in the United States on issues of liquor control. Most of these left the existent situation intact. In 10.8 per cent of the elections there was a change from one direction to another. Even here the forces were well balanced. In 45.3 per cent ( 592) of the 1,307 cases the voting unit went from Dry to Wet. In 54.7 per cent (715) of the cases the unit went from Wet to Dry.44

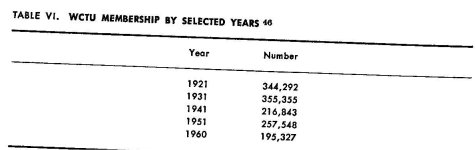

As an active movement, however, Temperance support is declining drastically. There is much concern in the WCTU, voiced in its journal and in interviews, for the future of the organization. It appears increasingly difficult to recruit young people into the movement. As the older members die out, the organization is not fed new membership from younger generations.45 Table VI shows how WCTU membership has declined since 1930. The past decade has even shown a reversal in the small growth of the 1940-50 decade.

The decline of the past decade has been consistent in all parts of the country. No state showed an increase in membership. While there has been a consistent increase in percentage of WCTU membership in the South and Midwest and a consistent drop since 1930 in percentage of membership from New England and the East, there has been an over-all decline in membership while the total population of the country has been increasing.

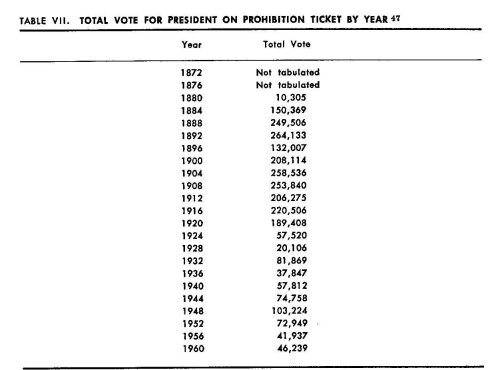

The same phenomenon of declining support is manifest in the electoral strength of the Prohibition Party. The Prohibition Party is the oldest third party in the United States. It has placed a candidate in every presidential election since 1872. While it has never been strong enough to capture an electoral vote, its strength has been significant in local and state elections in certain periods and in certain areas. Measured as a national party, the Prohibition Party has declined in strength since the pre-Prohibition era.

Even with a larger total electorate, the total Prohibition vote is lower than pre-Prohibition. Since Repeal, however, it has fluctuated considerably, although the past two elections have seen a lower vote than at any time since 1936.

The Future of the Temperance Movement

At present the Temperance movement is a declining but still functioning phenomenon. Three alternative approaches have emerged to the dilemma of the movement in contemporary America. While all of them, to some extent, are found in all facets of the movement, each tends to dominate one wing of the movement more than the others.

One approach is a narrowed concern with drinking and drinking legislation to the exclusion of other reforms or of general political participation. The National Temperance League follows this policy. Unlike its forerunner, it no longer places Prohibition, either at the national or the state level, at the head of its aims. The work is more modest, confined to local option, to maintenance of existing antiliquor legislation, and to education in Temperance sentiment. As a political pressure group it serves to marshal the limited power of the movement largely as a defensive maneuver, to prevent the Wets from eradicating the legal and political measures which limit the expansion of liquor sales. As a pressure group, the movement has been moderately successful in maintaining present restrictions on liquor advertising on radio and television. Especially when it operates with other, nonideological interests, the Temperance movement has been a fairly successful "veto group," preventing the passage of legislation detrimental to its interests but unable to pass its own.

A second approach, especially manifested in the WCTU, lies in spreading the cluster of activities to which the movement is oriented so as to include a number of reforms acceptable in middle-class church circles. This functions to mitigate the isolation of them movement from social areas of prestige and from major institutions. Among such reforms are narcotics prevention, chronic alcoholism, juvenile delinquency, censorship of obscene literature, and religious devotions. The emphasis of these activities is on assimilative reform and on cultural fundamentalism. The organization will work with groups in areas of alcoholism even though they are opposed to Prohibition and total abstinence. The thrust of the effort in this wider policy is toward eradicating the stereotype of the narrow, fanatical, and doctrinaire "blue-nose" of the famous Rollins Kirby cartoon of the Dry. The WCTU has even cautioned its members to dress with some gaiety, to be tactful toward non-members, and to avoid the mannerisms and actions of the "fanatic." Prohibition, while not disowned, is not emphasized, and the educational and pressure group aspects of the organization are given primacy. The subtitle of the WCTU periodical, "A Journal of Social Welfare," suggests the tone which is followed. Political issues outside of these generally accepted areas are excluded from organizational interest.

The third approach lies in capitalizing on the sources of isolation and protest among old middle-class citizens as they feel the discontents of a fading social status. This approach is clearly that of political extremism and middle-class protest. The platform of the Prohibition Party illustrates how Prohibition and total abstinence, as issues, are brought within the syndrome of the radical right. This is the classic position of the third party as a vehicle of generalized protest.

The prospect that any of these approaches will succeed in achieving a significant change in American drinking norms appears slim. As long as the Temperance movement is dependent on the Protestant churches for political, organizational, and cultural support it is doubtful that a firm rejection of moderate drinking in favor of total abstinence will occur. Protestantism no longer represents a cultural group sufficiently uniform to support the mobilized Temperance opinion it mustered in the 1920's. The socialization of each succeeding generation reduces the importance of abstinence as a symbol differentiating the respectable middle class from the nonrespectable drinkers. In order to stay within the orbits of churchgoing respectability the Temperance movement must minimize its indignation, accept Repeal, and be largely a vehicle of middle-class reform without any distinctive properties, except as a veto group for a constituency which is growing smaller.

The chance that the demand for liquor reform as a status symbol will again return in America is not dependent on drinking habits. In fact, while Americans have become less alcoholic they have accorded alcohol greater prestige. The future of alcohol reform depends on the general future of fundamentalist protest in the United States. Liquor control can become imbedded in the syndrome of political fundamentalism if the Temperance movement becomes allied to right-wing radicalism or if other radical rightist organizations absorb Temperance issues and present demands for alcohol reform. Something of this nature has begun to occur with the absorption of the position of the Southern white supremacist by the radical right. Both as an opportunistic measure and as expressive of the fundamentalist-modernist conflict, states' rights has become a symbol to which the political fundamentalist attaches himself.

In short, while the future of the movement as a direct attack on drinking seems to be limited, its role as a "holding movement" may possess greater possibilities. By a "holding movement" we refer to the fact that future crises unconnected with drinking may change the movement in directions which will be more significant for political success. There are many Americans who do not drink but to whom Temperance is not a burning issue. Any crisis which may create a generalized rightist neo-Populist movement contains the possibility that it may utilize the liquor industry as one of several bêtes noires and liquor reform as a symbol of revived prestige.

The separation of the old middle class from a specific role of dominance in major institutions, especially the churches, severely limits their role in politics. Cut adrift from a specific institutional mooring, their very weakness leads to the divergent tactics of extremism and of accommodation.

1 David Riesman, The Lonely Crowd (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1950), p. 32.

2 This distinction between local and cosmopolitan values and between local and mass society is discussed by several recent writers. See Arthur Vidich and Joseph Bensman, Small Town in Mass Society (New York: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1960); C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York: Oxford University Press, 1961), Ch. 2; Alvin W. Gouldner, "Cosmopolitans and Locals," Administrative Science Quarterly, 2 (December, 1957, March, 1958), 281-306, 444-480.

3 Edward Shils, "Mass Society and Its Culture," Daedalus, 89 (Spring, 1960), 288-314, at 288.

4 Riesman, op. cit., esp. Ch. 6; Leo Lowenthal, "Biographies in Popular Magazines," in Paul Lazarsfeld and Frank N. Stanton (eds.), Radio Research: 1942-43 (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1944), pp. 507-548. This corresponds to what Rostow refers to as the postindustrial stage of economic growth. W. W. Rostow, Stages of Economic Growth (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1960).

5 Vidich and Bensman, op. cit., p. 79.

6 Gregory Stone and William Form, "Instabilities in Status," American Sociological Review, 18 (April, 1953), 149-162, at 155.

7 Talcott Parsons, "Some Sociological Aspects of the Fascist Movements," in his Essays in Sociological Theory (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1954), pp. 124-141, at 136.

8 From an address by Ida B. Wise Smith, President of the NWCTU, to the 1934 annual convention. Annual Report of the NWCTU (1934), p. 81.

9 A statement by Mrs. D. L. Colvin, President of the NWCTU. Quoted in The Chicago Daily News (September 10, 1951).

10 Parsons, op. cit., p. 125.

11 From an editorial in The Union Signal (May 16, 1953), p. 8.

12 Martha Wolfenstein, "The Emergence of Fun Morality," in Eric Larrabee and Rolf Meyersohn (eds.), Mass Leisure (Glencoe, M.: The Free Press, 1958), pp. 86-96, at 92.

13 The term is used by David Riesman in his characterization of the inner-directed orientation to politics. Op. cit., pp. 190-199.

14 For a leading, middle-of-the-road economist's view see Paul Samuelson, Economics, 3rd ed. (New York: McCraw-Hill, 1955).

15 Keynes was quite aware of the implications of this change for the sense of psychological security of the old middle classes. ". . . this experience must modify social psychology toward the practice of saving and investment. What was deemed most secure has proved least so. He who neither spent nor 'speculated,' who made proper provision for his family; who sang hymns to security and observed most straitly the morals of the edified and the respectable injunctions of the worldly-wise—he, indeed, who gave fewest pledges to fortune has yet suffered her heaviest visitations." John Maynard Keynes, Essays in Persuasion (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1932), p. 91.

16 Here again is an instance of the negative reference group discussed in connection with contrast conceptions and drinking as a symbol of lower-class status (see Chapter 1). Whatever stems from scientific authority is immediately resisted by those who see science as an attack on their traditional symbols and sources of their authority. The quotation in the text is from James Rorty, in F. B. Exner and G. L. Woldblatt, The American Fluoridation Experiment, quoted in Kurt and Gladys Lang, Collective Dynamics (New York: Crowell and Co., 1960), p. 426.

17 Annual Report of the NWCTU (1936), P. 97.

18 Ibid. (1934), p. 51.

19 In 1934 one Baptist leader said to Franklin Roosevelt, "We are for you 96.8%. We cannot go the other 3.2." Quoted in Paul Carter, Decline and Revival of the Social Gospel: Social and Political Liberalism in American Protestant Churches, 1920-1940 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1956), p. 167.

20 The 1928 platform implied that the party would retire if it were proved that Smith was close to victory. See Kirk Porter and Donald Johnson, National Party Platforms, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1961), p. 279.

21 See the platforms of the Prohibition Party for 1932, 1936, and 1940 in ibid., pp. 337, 363, 388.

22 Quoted in Norman Furniss, The Fundamentalist Controversy, 1918-1931 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1954), p. 16.

23The Union Signal (August 9, 1952), p. 12. At this time there was a large portrait-photo of General MacArthur displayed behind the librarian's desk in the WCTU Library.

24 ibid. (September 13, 1952), p. 2. Colvin's remarks may be taken to represent Prohibition Party official sentiment. She was a staunch supporter of the party and her husband was one of its leading officials.

251bid. (September 27, 1952), p. 8.

26 Porter and Johnson, op. cit., p. 601.

27 See the collection of essays edited Ly Daniel Bell, The New American Right (New York: Criterion Books, 1955).

28 Edward Shils, The Torment of Secrecy (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1956), p. 231.

29 The wave of rightist sentiment during the period of McCarthyism (1950- 54) lacked strong anti-Semitic or anti-Catholic sentiments. Both Jews and Catholics were among leading McCarthy supporters. It testified to the diminution of these tensions as central to contemporary antiforeign sentiments. See the essay by Seymour Lipset, "The Sources of the Radical Right," in Bell (ed.), op. cit., pp. 166-234, at 201-206.

30 From a speech by Cannon, given at Cambridge, Maryland, during the 1928 campaign. Quoted from The Baltimore Sun in Virginius Dabney, Dry Messiah (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1949), p. 188.

31 See the 1928 platform of the Prohibition Party in Porter and Johnson, op. cit., p. 279.

32 The National Prohibitionist (November, 1960), p. 2; (April, 1961), p. 3.

33 The works of the late Ernest Cordon contained many references to the role of Jews and Catholics in the liquor industry. See The Wrecking of the 18th Amendment (Francestown, N.H.: The Alcohol Information Press, 1943), pp. 147, 158.

34 Gerald Winrod, head of the Defenders of the Christian Faith, and the representative of the Disciples of Christ both attacked, by implication, the role of Jews in the press and in the liquor industry at a Senate investigation into liquor advertising. U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, Liquor Advertising (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1950), p. 112.

35 The National Prohibitionist (February, 1961), p. 1.

36 Quoted in ibid. (November, 1960), p. 2.

37 Harry Everingham, "Federal Md—Enemy of Education," ibid. (May, 1961), pp. 1, 4.

38 See the 1948 platform of the Prohibition Party, Porter and Johnson, op. cit., p. 447, and the report of the WCTU Department of International Relations for Peace, Annual Report of the NWCTU (1952), p. 128. The anti-militarism of the Prohibitionists is consistent with their Populist ideology. Both posited a conspiracy of profiteers behind military alliances. See Wayne J. Cole's account of this in his history of the movement, America First (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1953),

39 Quoted in The Chicago Daily News (December 19, 1953), p. 24.

40 Raymond McCarthy (ed.), Drinking and Intoxication (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, and New Haven, Conn.: Yale Center of Alcohol Studies, 1959), p. 179.

41 See the discussion of this above, Chapter 5, pp. 134-135.

42 Based on statistics compiled by the Distilled Spirits Institute, Anntuz/ Report (1939), Appendix E; (1959), p. 51.

43Ibid. (1959), pp. 46 ff.

44 ibid., p. 54.

45 This is described further in my article "The Problem of Generations in an Organizational Structure," Social Forces, 35 (May, 1957), pp. 323-330.

46 Based on the treasurer's reports, Annual Reports of the NWCTU. These figures can be presumed fairly accurate. A state is required to pay a uniform dues to the national treasury for each member enrolled. The vote of the state delegation to the national convention is based on this. Hence the importance of accurate reporting to the national treasurer.

47 U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1960), p. 682. These figures may be grossly underenumerated. Officials of minority parties claim that their votes are often not tabulated. The matter has never been studied, but the author's personal experience at one precinct suggests there may be merit to this claim.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|