5 Moral Indignation and Status Conflict

| Books - Symbolic Crusade |

Drug Abuse

5 Moral Indignation and Status Conflict

The coercive reformer reacts to nonconformity with anger and indignation. Sympathy and pity toward the victim have no place in his emotional orientation. The coercive response came to dominate the Temperance movement during the first 30 years of this century. In Prohibition and its enforcement, hostility, hatred, and anger toward the enemy were the major feelings which nurtured the movement. Armed with the response of indignation at their declining social position, the adherents of Temperance sought a symbolic victory through legislation which, even if it failed to regulate drinking, did indicate whose morality was publicly dominant.

The analysis of the Prohibition and post-Repeal periods provides an opportunity for understanding the relation between moral indignation and social structure. We are able to observe both the process of symbolic solutions to conflict and the indignant response to loss of status.

Indignation implies a righteous hostility. Webster defines "indignant" as "wrathful because of unjust or unworthy treatment." Durkheim speaks of crime as leading to reactions of a passionate nature among the law-abiding and directed toward the punishment of the criminal? Svend Ranulf sees indignation as the disposition to inflict punishment.3 Max Scheler uses a somewhat similar concept of ressentiment, a psychological disposition involving the free use of emotions of spite, vengeance, hatred, wickedness, jealousy, malice, and envy.4 All these definitions have in common the conception of an affective state in which the indignant person feels a just or rightful hostility toward the subject of his indignation and seeks to punish him in some fashion.

Moral indignation brings into play the quality of disinterested anger. The morally indignant person directs his hostility at one whose transgression is solely moral. The action does not impinge upon the life or behavior of the morally indignant judge.5 Moral indignation is the hostile response of the norm-upholder to the norm-violator where no direct, personal advantage to the norm-upholder is at stake. It is exemplified in the reactions of conventional citizens to those who lead unconventional lives. The intensity of hatred and persecution which the homosexual, the Bohemian, and the drug addict meet in American society today is illustrative of moral indignation. We will exempt attitudes toward political radicalism or delinquency since these are interpretable as affecting the direct interests of the conventional person in his institutions. The radical desires change in the institutions within whose framework the conventional person lives. The delinquent poses a threat to property or person.

INDIGNATION AND PATTERNED EVASION OF NORMS

Two major theories have been advanced to explain the sources and functions of moral indignation. One is the functional theory of Emile Durkheim. In his analysis of legal norms, Durkheim interpreted the disposition to punish criminals as a response which maintains the respect for law and morality on which social order depends. Since norms derive their force from their sacredness and uncontested nature, crime shows that this respect is not universal. "Crime thus damages this unanimity which is the source of their authority. If, then, when it is committed the consciences it offends do not unite themselves to give mutual evidence of their communion and recognize that the case is anomalous, they would be permanently unsettled. They must re-inforce themselves by mutual assurances that they are always agreed." 6

This functional theory is partially supported by our analysis of the two forms of reform reaction, assimilative and coercive. The assimilative reaction is not one of indignation and thus contradicts the Durkheimian assumption that the response to norms-violation is always a punishing attitude. However, our analysis concluded that assimilative reform occurred where the validity of the norms were not threatened. Where they were threatened, coercive reform was more likely, with its hostile and angry tones. Durkheim's view of the punishment orientation as functioning to uphold the validity of the norm is strengthened by this conclusion.

A second theory is the psychological one advanced, in different forms, by Svend Ranulf and also by Max Scheler. Both interpreted laws attempting to enforce sexual, sumptuary, and other moralities as one form of envy directed by less privileged classes toward more privileged classes: "The disinterested tendency to inflict punishment is a distinctive characteristic of the lower middle class, that is a social class living under conditions which force its members to an extraordinarily high degree of self-restraint and subject them to much frustration of natural desires . . . moral indignation is a kind of resentment caused by the repression of instincts." 7 Like Ranulf, Scheler also sees the reaction of ressentiment as one in which the authors of moral condemnation themselves wish to engage in the condemned behavior. Unable to satisfy the desires as others can, they end by condemning the satisfied. "In ressentiment one condemns what one secretly craves; in rebellion one condemns the craving itself." 8

It is difficult to explain coercive reform in the Temperance movement in accordance with this theory. If we argue that hostility, anger, and indignation are reactions to behavior which we, ourselves, would like to follow, this reasoning is inconsistent with the fact of assimilative reform. We have shown that norms-violation is not necessarily responded to with anger. The same norm can be violated in different situations of status designation. Not the behavior but the implied threat which the behavior held for the status of the norm was the crucial variable. If the Temperance adherent secretly craved drink, he should have responded the same way to all violations of the norm. He didn't.

The assertion that the abstainer unconsciously admires and envies the behavior of the drinker assumes a "natural" craving for the joys of impulse gratification and drinking. The norms-violators are then threats to the tenuous system of internal controls which the Temperance adherent has constructed. This viewpoint also fails as an explanation of the Temperance movement. That movement was seldom directed, as we have shown, against members of the same class or even the same community as the Temperance supporter. In its most coercive form, it was directed outward, at the Catholic, urban, lower classes or the urban, high-status church member of the upper classes.

Both the functional theory of the need for norms unanimity and the social-psychological theory of reaction-formation present further difficulties in application to modern societies, and to the United States in particular. To speak of "the norms of a society" is a vast abstraction when we refer to the complex of divergent classes, ethnic groups, cultures, and regions that are part of the United States. "Within a given political entity such as a nation the differentiation of groups may proceed to a degree that we have to be quite cautious in speaking of a culture at all. . . ." 9 Divergent cultures, subcultures, and contracultures have shown a remarkable ability to persist in American society.'° Rather than the unanimity which Durkheim thought essential, norms of tolerance appear functionally necessary to modern society. In many areas, such as religious tolerance, such norms have been developed and a pluralistic social organization made a major value in American life.

Quite evidently the movement to reform drinking habits and to prohibit liquor and beer sales is not a movement to tolerate differences. The adage that one man's moral turpitude is another man's innocent pleasure has rio place in the attitude of the Temperance adherent. On the other hand, the difficulties in enforcing Prohibition in communities where it is anathema seemed, and were, almost unbeatable. To understand what is at stake in the movement, we need to analyze the existence at the same time of both official, legal norms and illegal but recurrent patterns of behavior. This is a characteristic situation in modem societies. Robin Williams has called this mode of organization the "patterned evasion of norms." 11 This was the case during Prohibition.

The evasion of normative patterns occurs when a pattern of behavior regularly expected in the society is performed and is unpunished although the written, publicly stated norms of the society call for punishment and proscribe the behavior. Two examples of institutionalized evasion are the methods of obtaining divorce and the abortion "racket." The legal grounds for divorce proscribe collusion between plaintiff and defendant, but most divorces are mutually agreed upon by the parties. The form of the trial as a battle between two parties is a fiction. The grounds for divorce are usually narrow, and the parties, including witnesses, frequently perjure themselves. The legal fictions are accepted and no one is called to legal account for such collusion or perjury. The abortion case shows a similar pattern of accepted evasion. Abortions, except for a few specific reasons, are illegal in all states. Nevertheless abortions are obtainable, through illegal action or through the willingness of physicians granting medical diagnoses which, while false, will sustain "legal" abortions.

Williams has interpreted institutional evasion as functional in a society of great cultural inconsistencies. Those groups who adhere to the public norm see it upheld at a public level while those whose cultural norms are offended are able to pursue the behavior they find legitimate. Conflict between the two groups is thus minimized The existence of divergent and potentially conflicting cultures "does not necessarily constitute any particular problem for the society as a whole so long as the two groups are not in direct interaction and do not directly confront one another's differing orientations." 12

This formulation of the systematic evasion of public norms does not help us understand why groups struggle to define public norms in one way rather than another. If tolerance is the fact of social organization, why struggle over the legal and moral norms at the public level? The public level, of mass communications, community and nationwide institutions, government and legal action is precisely an area in which the divergent groups do interact and in which the public definition of a norm has consequences. Doctors cannot make their support of abortion visible to all nor can witnesses admit to strangers that they have perjured themselves in a divorce suit. Institutionalized evasions are covert; public, overt evasion is likely to result in punishment.

While systematic evasion of rules may be functional in minimizing conflict between subcultures, it does not remove the significance of public affirmation. For the cultural group that shares the normative pattern which is evaded, public affirmation has several important consequences.

1. It prevents the perception of the large extent of norms-violation. The violator of the public norms is not observed by those who do not directly interact with his cultural groups. He sees the norm-violator being punished and hence assumes that the norm is being reasonably obeyed.

2. It directs the major institutions of the society to the support of its norms. The covert nature of abortions in the United States is affirmed by the fact that schools (including medical schools), churches, newspapers, and government neither sanction abortions nor provide information on how to obtain them.

3. The fact of affirmation is a positive statement of the worth or value of the particular subculture vis-à-vis other subcultures in the society. It is in this sense that public affirmation is significant for the status of a group. It demonstrates their dominance in the power structure and the prestige accorded them in the total society.

This last point is crucial. Prestige in the total, national society is not the same as prestige in the small, local group. Social status is not simply a matter of where one stands in relation to those with whom he comes in contact. It is also a matter of where he stands vis-à-vis other groups in the total society. His perception of his status in the society comes either from acts of deference performed toward him as he interacts directly or from the public acts in which his norms have power and prestige. Status is reciprocal. It must be bestowed by both subordinates and peers.

The public affirmation of norms is thus a sign of their societal dominance. It is a symbol of the social status and prestige accorded to those who are identified with the public norms. Moral indignation, in this case, arises when that status is threatened. The object of indignation has not only violated my norm; he has violated the socially dominant norm and I have a legitimate right to indignation. Scheler partially recognized this. He wrote that moral indignation was a quality more likely to be found among lower-class white-collar workers and other petite bourgeoisie in egalitarian rather than in nonegalitarian cultures. In an egalitarian culture the powerlessness of the petite bourgeoisie belied the norm of equality.13 It is the discrepancy between the expected public deference and the actual injury to prestige and power that generates the hostility of indignation—the feeling that one has been unjustly treated.

These ideas receive confirmation in two respects in the history of Temperance. In the period of Prohibition, the legal status of abstinence produced a strong sense of societal dominance among Temperance adherents. It was as important to maintain the legal affirmation of Prohibition as it was to enforce it. Repeal was thus more than a political defeat. It represented the loss of societal validity and the decline of social status of the Protestant, rural, native upholders of Prohibition.

PROHIBITION: SYMBOL OF MIDDLE-CLASS DOMINATION

During the 1920's critics of Prohibition often maintained that passage of the Eighteenth Amendment was a political fluke, unrepresentative of any widespread sentiment in American life. They held that it had been passed during wartime while an energetic nation was looking the other way. This interpretation is decidedly belied by the Prohibition agitations of the early twentieth century. In the period 1906-17, 26 states passed prohibitionary legislation, although of diverse scope. In 18 of these states, the proposal had been adopted at state elections. In 1914 the House of Representatives had voted in favor of a constitutional amendment. When the Eighteenth Amendment was ratified on January 20, 1919, it was the fruition of a wave of successful Temperance agitation and legislation in the preceding 20 years.

As critics claimed, the structure of state and national legislatures was most favorable to rural constituencies. The pressure politics of the Anti-Saloon League, backed by the organized influence of the Protestant churches, was probably an essential element in the victory. The electoral victories at the state level were close, an average of less than 4 per cent differences between Wets and Drys.14 These facts lessen the validity of assertions that Prohibition represented the enthusiastic endorsement of most Americans. Nevertheless, them electoral and legislative victories, the movement toward state Prohibition, and the successful power of the Anti-Saloon League do show that, within the structure of American politics, the Temperance forces were strong. While the Anti-Saloon League may have been unscrupulous at times, its power rested on the genuine sentiment of the Protestant church member. That sentiment might be mobilized by effective organization. It was not manufactured by it.

The passage of the Eighteenth Amendment did not produce a drastic decline in anti-Temperance sentiment. In most communities and at most times before Prohibition, this was a significant segment of opinion. If by the victory of the Temperance movement we mean a change in the cultural legitimacy of drinking, there is little evidence that this occurred. Neither is there much evidence that the sale of liquor disappeared. The bootlegging and systematic evasion of the Volstead Act, especially in urban centers, was evident even to the most loyal and enthusiastic Prohibitionist.15 The conflict between cultures that had generated the pre-Prohibition hostilities continued and intensified throughout the Prohibition years.

The Prohibition period is often used as a striking instance of institutional evasion. Even during Prohibition, however, there is much to suggest that the number of drinkers and the frequency of drinking greatly declined. Since consumption figures based on tax receipts are lacking, estimates of actual drinking conditions remain most inexact. Jellinek estimates that the rate of alcohol consumption per capita of population of drinking age during Prohibition was about one-half of that for the average of the four years preceding Prohibition.16 If we assume that moderate drinkers were more likely to have abstained entirely, perhaps the heavy drinkers were not greatly affected by the law. A more telling indication of drinking quantity is given by the rates of alcoholism during the decade of the 1930's. The rates from 1920 to 1945, as studied by Jellinek, show a decided drop in alcoholism as compared to the 1910 and 1915 rates. Since chronic alcoholism is a reflection of past drinking habits (approximately 10-15 years) and indicated by deaths from cirrhosis of the liver, it is good evidence of the changed habits brought about during state and national Prohibition in the early twentieth century. Heavy drinking was less frequent.

Whether or not the law was evaded in those areas where it was least supported by cultural beliefs, the doctrine of Prohibition was given a position as the officially sanctioned policy of the nation. No public official could openly evade it. Whatever his covert habits, the President of the United States lent it his sanction in his public behavior. It was endorsed by legislative majorities and given mythical support by the Constitution. Temperance materials of this period stressed the "unAmerican" connotations of Wet opinion and depicted the violator of the Dry law as unpatriotic, a nihilist without respect for law, and an opponent of constitutional government. Speaking before the annual convention of the National Woman's Christian Temperance Union in 1927, Senator Capper said that refusal to obey a law is equivalent to treason»

In two respects the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment made the Temperance position dominant. First, it actually did restrict the ability of the person to take a drink. It was a fact of life that liquor, beer, and wine were sold covertly and not openly; that public exposure of evasion might force fines or jail or both. People were sentenced to prison and punishment did exist, even though on a scale well below that of less evaded norms, such as those against stealing." Second, the official status of a law lent it a sanction which made it the societal behavior at the level of public visibility. In any argument over the recognition of one culture as of greater worth or respect than another the public definition supported the abstaining, dry proclivities of the Protestant middle classes and denigrated the less ascetic habits of the metropolitan Catholic, the secularist, and others who "struck a blow for liberty."

Enforcement and Symbol Protection

Faced by the systematic evasion of a legal norm, the upholders of the norm can press their power and authority further and attempt eradication, even at the price of social conflict. They can also accept the compromise between legal acceptance and rejection which a system of institutionalized evasion represents, taking comfort from the small crumbs of enforcement and the symbolic satisfactions of being the chosen in the contest for societal dominance. The action of Temperance forces during the Prohibition decade strongly suggests that they did not utilize their political power to demand as much enforcement as they might have obtained. The passage of the legislation itself presented satisfactions which could not be endangered by too zealous an effort to enforce it.

Whether or not the Volstead Act and the various state laws supporting it could have been totally enforced is a moot question, although it is doubtful that evasion could have been totally stopped. What does stand out, however, is that the Volstead Act, which contained the legal sanctions to enforce the Eighteenth Amendment, never received appropriations adequate to the attempt. New personnel and new methods of prohibition organization were tried. Repeatedly they floundered on the unwillingness of federal and state legislatures to grant the necessary funds that would have made possible a large legal and police organization to cope with bootlegging.

The power of the Anti-Saloon League and the organized Drys was sometimes astounding. From the passage of the Webb-Kenyon Act in 1913, forbidding the importation of alcohol from Wet to Dry states, to the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment the Drys constituted one of the most effective pressure groups in the history of American politics.'9 With the passage of the Prohibition Amendment they were at the height of power. In the elections of 1920 and 1922 they surpassed this and showed even greater power by defeating a number of incumbents who had dared to oppose Dry legislation. Despite this strength little was done to provide effective enforcement. A policy of "nullification by inaction" was set by Congress. The Dry forces possessed considerable power to multiply the appropriations but they made no major efforts to raise the sums needed. "The law limped on. It was scarcely the business of the prohibition Bureau to quarrel with its peers." 20

The Drys were in the common dilemma of those who support a law which a significant minority oppose and which is illegitimate to them. The Temperance forces had claimed that they represented the legitimate position of most citizens. To maintain that the law was not enforceable without great sums of money and much police action was to deny the legitimacy claimed for it. Furthermore, increased appropriations might stimulate the opposition of those who were rallied by fears of high taxation.21 In the final analysis, a system of institutionalized evasion persists because the upholders of the official norm fear that thorough enforcement will so enrage the objects of coercive reform they they will threaten the official status of the norm itself. Some Temperance personnel argued that time would lead to a new generation who would accept Prohibition more adequately than had the old.

The self-imposed limitations on the use of their political power suggests that the Prohibitionists were at least content to settle for the public validity of Temperance even though the factual situation was a long way from the utopia of a Dry society. It was evident to a number of Drys, however, that this could not be sustained without greater effort. The domination of the rural powers in politics was threatened by the rise in urban population and the higher birth rate of first and second generation immigrants. By 1924 it was apparent that Catholic, urban power was now a major factor in the Democratic Party.22 If Prohibition were to be enforced, appropriations and greater use of Dry power were needed than had been used in gaining the Eighteenth Amendment. The entire episode reinforces the belief in the importance of the passage of the legislation as itself granting great satisfactions to its adherents, sufficient enough to cushion the blows of a widely publicized evasion of the Prohibition norm in just those areas where the original movement sought to expand control.

In another way, the corruption and inadequacies in Prohibition enforcement served as a convenient device to hide the extent to which the norms of Temperance were not shared by a great many citizens. A more thorough enforcement effort might well have displayed the intensity of opposition and hatred the law incurred in subcultures where drinking had been part of the accepted way of life. It is still Temperance doctrine that Prohibition was never really tried, was foiled in practice by its enemies and cannot be said to have been rejected by the American people.23 Here, again, what is protected is the claim to legitimacy and social dominance.

Murray Edelman has shown that interest groups are frequently rendered politically quiescent by the mere passage of legislation which has their support.24 The citizen is satisfied that his interests are being championed and fails to perceive that enforcement is lax and that the substantive results of enactment are not at all what he had expected and are sometimes contradictory. The failure of the Anti-Trust Act to control business price regulation has not diminished the feeling of economic security derived by many from the existence of such legislation. The attitude of the Temperance movement to Prohibition contained much that is similar. Having already attained symbolic victory, the Prohibitionist was unwilling to press too hard for a more tangible kind of change. The good citizens of small towns, hamlets, and farms of rural America saw less of drunkenness than they had before the Volstead Act had hallowed a sober world. If Prohibition was systematically evaded in the cities, the urban Temperance adherent did not come into contact with its covert operations. The Dry knew that somewhere in the evil jungles of urban society Law and Morality were being mocked, but there was little question about whose law and whose morality they were. It was his culture that had to be evaded and his morality that was transgressed.

Cultural Conflict and Symbolic Victory

What Prohibition symbolized was the superior power and prestige of the old middle class in American society. The threat of decline in that position had made explicit actions of government necessary to defend it. Legislation did this in two ways. It demonstrated the power of the old middle classes by showing that they could mobilize sufficient political strength to bring it about and it gave dominance to the character and style of old middle-class life in contrast to that of the urban lower and middle classes.

The power of the Protestant, rural, native American was greater than that of the Eastern upper classes, the Catholic and Jewish immigrants, and the urbanized middle class. This was the lineup of the electoral struggle. In this struggle the champions of drinking represented cultural enemies and they had lost. James Cannon, the Methodist bishop who was among the handful of major leaders of the Prohibition movement during its decade of power, expressed this side of the conflict: "In any discussion of 'why' the Eighteenth Amendment was ratified, it cannot be too strongly emphasized that the Prohibition movement in the United States has been Christian in its inspiration and has been dependent for its persistent vitality and victorious leadership upon the active and, finally, the undivided support of American Protestantism, with support from some Roman Catholics." 25

The Temperance movement had utilized the theme of alien support of drinking in its campaign for wartime Prohibition. At that time they had attacked the brewing industry as German in leadership and pro-Kaiser in the war.26 It was more than effective propaganda, however. It was one aspect of a conflict of cultures which was rooted in divergent values. Anna Gordon, then President of the WCTU, hailed wartime Prohibition as a patriotic victory over "the Un-American liquor traffic." From the beginning, she said, the liquor traffic in America has been "of alien and autocratic origin." 27 Even the assimilative reform of work with immigrants took on this tone of hostility and concern for dominance. In 1929 Athena Marmaroff, Director of Ellis Island Work for the WCTU (a program of Americanization of immigrants), complained that the laws, especially the Eighteenth Amendment, were broken frequently by foreigners. "Let us see that the laws are obeyed and those who do not like them or obey them should be sent back to the country from which they came. Prohibition is here to stay and let us work to see that it is enforced." 28

In legitimating the character and style of the old middle class, Prohibition stood as a symbol of the general system of ascetic behavior with which the Protestant middle classes had been identified. Not only was Temperance at stake but so too was the Temperance ethic which provided its rationale and its moral energy. Supporters of Prohibition identified the struggle to dry up American society as part of the defense of a "way of life" against groups who subscribed to other cultures. Prohibition was not seen as an isolated issue but as one which pitted cultures against each other. Speaking to a WCTU national convention in 1928, Ella Boole ( then President of the WCTU ) said:

This is the United States of America, my country and I love it. From the towering Statue of Liberty to the sun-kissed Golden Gate, this is my country. It is all I have. It is the foundation and security for my property, home and God.

As my forefathers worked and struggled to build it, so will I work and struggle to maintain it unsoiled by foreign influences, uncontaminated by vicious mind poison. Its people are my people, its institutions are my institutions, its strength is my strength, its traditions are my traditions, its enemies are my enemies and its enemies shall not prevail.29

Mrs. Boole made it clear to her listeners that the enemies she had in mind were those who opposed Prohibition and evaded its laws. She had equated Prohibition with the total American culture.

The victory of the Prohibitionists and the later fight against Repeal only intensified the cultural conflict and further polarized the forces of urban and rural, Catholic and Protestant, immigrant and native. The disposition to assimilate the nonconformer was even further minimized, as anti-Prohibition forces became organized for Repeal. The Temperance movement became an active supporter of legislation to curtail immigration drastically.

Increasingly the problem of liquor control became the central issue around which was posed the conflict between new and old cultural forces in American society. On the one side were the Wets—a union of cultural sophistication and secularism with Catholic, lower-class traditionalism. These represented the new additions to the American population that made up the increasingly powerful political forces of urban politics. On the other were the defenders of fundamental religion, of old moral virtues, of the ascetic, cautious, and sober middle class that had been the ideal of Americans in the nineteenth century.

In Alfred E. Smith the Wets found a perfect symbol of their ways of life—a champion of progressive liberalism through social welfare, an urban type whose speech and sentiments manifested the "sidewalks of New York" where he had been reared. He was in many ways the best of the machine politicians, loyal to his friends, a genial good fellow, and a deep defender of that urban underdog who worked in factories, spoke broken English, and wanted a good time on Sundays.

If Smith was the symbol of the Wets, then William Jennings Bryan was the epitome of the Drys. He was born in a small town in rural Illinois and raised in the farmland of Nebraska. The Scopes trial dramatized again Bryan's religious fundamentalism, which his Biblical references had already made a part of American oratorical history. More than any other political figure it was Bryan who had been the champion of the rural underdog, who depended on the land, the railroads, and the banks for his livelihood, whose roots were several generations in America, and who treasured the quiet and peace of a Protestant Sunday.

These cultural dichotomies became increasingly sharpened in the Prohibition issue. The pluralism of political life which had made possible a union of urban and rural social welfare concerns in the Populist-Progressivist alliance and in assimilative Temperance reform was difficult to sustain as Prohibition ranged one culture against another. The Dry, the Protestant, the fundamentalist, the neo-Populist, the nativist were increasingly the same person. It was difficult to take one position and avoid the others. This tended to push the moderate elements out of the movement and to emphasize the others. The Federal Council of Churches of Christ, a moderate, welfare-oriented group, had been enthusiastic contributors to the campaign for legislative Prohibition. Antipathy to nativism and fundamentalism made them cool to the defense of the amendment. Bryan, in his struggle against Smith's potential nomination in 1924, came to the defense of the Ku Klux Klan and the attitude of nativist hostility to immigration. While the intellectual, the political liberal, and the assimilative reformer might have seen Temperance as an ally to other causes, this was less and less possible as the Prohibition decade continued and the Prohibitionists turned their cause increasingly into a crusade against urbanism, immigration, and Catholicism.

What was more than ever at stake in the symbol of Prohibition was the status of the old middle classes in America. The threat of Repeal carried with it the fear of status decline which had been offset by the Prohibition victory itself. A spokesman for the Anti-Saloon League responded to proposals for referenda on repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment by an attack on the cities and identification of American civilization with rural America: "When the great cities of America actually come to dominate the states and dictate the policies of the nation, the process of decay in our boasted American civilization will have begun."30 Here was the same appeal to rural virtue and anti-urbanism that had characterized Bryan's Cross of Gold speech in 1896. The neo-Populism of Prohibition was a political philosophy devoid of economic content but filled with the cultural tones of an attacked status group.

REPEAL AND STATUS LOSS

When the Eighteenth Amendment was repealed it meant the repudiation of old middle-class virtues and the end of rural, Protestant dominance. This is what was at issue in the clash between the Wets and the Drys. Victory had bolstered the prestige of the old middle classes. Defeat meant decline. Temperance norms were now officially illegitimate and rejected as socially valid ways of behaving.

The repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment has never been subject to a scholarly analysis. In the absence of definitive research, explanations of Repeal have reflected the pros and cons of Wet and Dry convictions. Wets have chosen to consider the Dry decade as an experiment that failed when its unenforceability was obvious to all but the bigoted and the fanatical. Drys have resorted to cries of trickery or, in more directly Populist spirit, held the wealthy and the powerful accountable for an effort to increase sources of tax revenue through beer and liquor sales.

It seems likely that the failure to enforce Prohibition in urban areas need not have destroyed its status as a legal pattern. The Prohibition episode is constantly used as evidence that law cannot effect social change. The bootlegging industry is depicted as the disorganizing consequence of Prohibition. It is true, however, that institutionalized systems of evasion have often been maintained over very long periods of time without damaging the symbolic status and social validity of the legal norms. This has been the case in prostitution, gambling, drug addiction, political corruption, abortion, and the other nonconformist actions called "business crimes." This might well have happened in the case of Prohibition. The ability of the underworld, the politician, and the police to regulate such institutions in concert is a major finding of criminologists and students of urban communities.31 Bootlegging in its early stages, like most American industries, displayed the disorder of individualistic competition. By the late 1920's it was beginning to move into the stage of monopolistic competition which has since characterized the regulation of much crime in America.

Of course, the rising power of urban political forces might well have doomed even an orderly system of institutionalized evasion. In the early thirties this was not yet the case. Alfred E. Smith had been defeated by a wide majority in an election in which the Prohibition Amendment was a major issue. When Herbert Hoover was elected President, Temperance forces were powerful supports to his victory.

The most significant element in the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment was not directly related to the cultural conflicts and struggle for status that had precipitated the Prohibition issue. It was the change in the tone of political life brought about by the Great Depression that killed the Eighteenth Amendment. In 1929 the amendment was safely in the Constitution, having survived the attack of the 1928 election. By 1932 neither major political party made its support a part of their platform. Two things had happened. The Depression had enormously strengthened the demand for increased employment and tax revenues which a reopened beer and liquor industry would bring, and it had made issues of status secondary to economic and class issues.

Congressional hearings on bills to modify or repeal Prohibition show the effect of economic arguments against Prohibition. In 1926 there were few witnesses in opposition. The argument against the Drys was couched in the logic of personal liberty.32 In 1930 many unions appeared and took a strong stand against the amendment on the grounds that Repeal would put men back to work. The same was true of the 1932 hearings.33 They contain pleas for Repeal by the Lithographers' Union (makers of bottle labels), the Glass Blowers' Union, and the Allied Association of Hotel and Stewards' Associations, as well as other unions with a direct interest in the alcoholic beverage industries. By 1930 both the American Federation of Labor and the National Association of Manufacturers had come out for Repeal.

The economic argument was twofold: put men back to work and provide another source for tax revenues. With the large decline in national prosperity, the question of tax relief seemed most important to businessmen who had championed Prohibition as the way to a sober and reliable work force.34 In 1926 the DuPonts swung over to active opposition to the Drys. Even such stalwarts of moral reform as John D. Rockefeller and S. S. Kresge left the movement in 1932. Shrinking federal revenues were an enormous detriment to the Drys.36

More important, perhaps, was the tendency for the Depression to minimize the importance of status politics. Tangible economic needs were paramount. Whatever the cultural differences between the lower-class urban workers and the rural farmers they were both in desperate financial straits. Not status groups but economic classes were now the salient axes of political movement. In 1929 The Christian Advocate listed enforcement of the Volstead Act as the most serious problem facing America.36 In 1932, with 15 million men out of work, this statement would have been more tragic than ludicrous.

Despite the decline in status issues, Repeal was nevertheless experienced as a loss of status for the old middle classes. In 1915 Anna Gordon, President of the WCTU, had described the growing dominance of Temperance in national life in terms of increasing prestige: "Total abstinence is no longer a ridiculed fanaticism. It sits in regal state on the throne of empires and of kingdoms and in republics sways, in ever increasing measure, the voting citizenship."37 After Repeal this was clearly not the case. Of the 37 states holding referenda on Repeal, only in five (North Carolina, Mississippi, Kansas, Oklahoma, and South Carolina) was there a majority vote against Repeal.38 In 1911, midway in the movement for state and national Prohibition, 50 per cent of the American population lived in Dry areas.39In 1940 18.3 per cent were living in Dry areas.40

Status Decline in the Temperance Movement

The symbolic decline has also been accompanied by an actual shift in the status of the Temperance adherent. This has meant that Temperance adherence is no longer prestigeful even in the communities which used to be sources of strong Temperance support. "People don't like us," said one WCTU local leader in a metropolitan city. An articulate and committed WCTU member stated the same result in terms of historical change. She described her experience in a small rural New York state town: ". . . this isn't the organization it used to be. It isn't popular you know. The public thinks of us—let's face it—as a bunch of old women, as frowzy fanatics. I've been viewed as queer, as an old fogey, for belonging to the WCTU. . . . This attitude was not true thirty years ago."

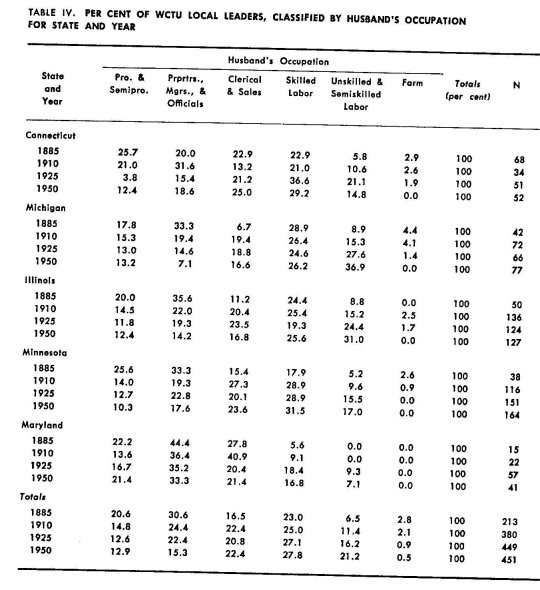

Between 1925 and 1950 the local leadership of the WCTU changed in its social characteristics. The percentage of women from upper middle-class background declined while the percentage from lower middle- and lower-class backgrounds increased. Data on the occupations of the husbands of WCTU local leaders is presented in Table IV (for sources see Chapter 3, p. 81, n. 36).

Table IV indicates the lessened prestige of the movement. Over the 65 years of WCTU membership surveyed there has been a steady decrease in the representation from high-status occupations and a steady increase in the representation from lower-status occupational groups. In 1885 the professionals and businessmen made up more than 50 per cent of the occupations represented among WCTU local presidents studied. (This also lends credence to our view of the upper middle-class nature of assimilative reform.) By 1950 this group had declined to almost one-fourth. The decline in status after Repeal is even more pronounced than is indicated by the table. In 1925, the two relatively low-status professional categories of clergymen and teachers accounted for 32.1 per cent of all the professionals in the sample. In 1950 they accounted for 61.4 per cent of the professionals.

These conclusions of a diminished status are further reinforced by the statements of WCTU people themselves. Many of the local leaders whom we talked to said that it is more difficult to recruit people with local prestige today than it was during Prohibition. Wives of doctors and lawyers and women who are teachers were reported as much harder to interest in the cause. "I remember," said one woman in New York State, "when the family lived in that house. They were the finest people in the town and they were Temperance people." Upper middle-class, Protestant, small-town people are less prone to be active in Temperance work than they were two and three decades ago. As a number of WCTU members have themselves mentioned, the attitude has emerged that "we ladies who are against taking a cocktail are a little queer."

MORAL INDIGNATION AND THE CRISIS OF LEGITIMACY

The decline in the status of the active worker in Temperance is probably less significant than the decline in the legitimacy and dominance of Temperance norms. Since the repeal of Prohibition, a crisis has developed in the relation between Temperance and social status. Where once the abstainer could identify himself with the publicly dominant norms of his own community and reference group, today he is more likely to find that Temperance ideals are deviant even within the Protestant middle-class society to which he has felt affiliated. Temperance norms are increasingly illegitimate or invalid. As one minister has put it: "Once you were a queer if you imbibed; now you are a queer if you don't." 41

American Alcohol Consumption

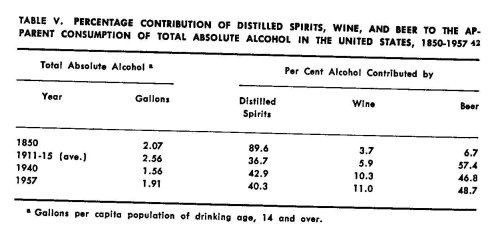

In order to understand the shift that has taken place in American attitudes toward drinking it is necessary to analyze the changes in the composition of American drinking. In the period between 1850 and 1915 there was a drastic change in the use of distilled spirits and beer. Table V shows that while we were once primarily a nation of liquor drinkers we have now become a nation of beer drinkers as well.

While the total amount of all alcoholic beverages consumed per capita of population of drinking age (14 and over) is much higher than it was in the periods before World War I, the per capita amount of alcohol consumed is much less. This is a result of a shift from liquor to beer in the drinking patterns of the society. The change toward greater beer drinking and less distilled spirits indicates a change from a pattern of extremes to one of moderation. A heavy consumption of distilled spirits and a low consumption of beer suggests there are few drinkers but that those who are drink heavily. A high consumption of beer indicates many users of alcohol but relatively few heavy drinkers. "The early Temperance societies thus had a strong case and their contention that 3 out of every 10 users became chronic alcoholics dates from experience in the nineteenth century. Under present-day drinking habits approximately 3 drinkers out of every 200 become chronic alcoholics." 43

The period before World War I and during the wave of state prohibitory legislation marks the high point in American drinking. During no year since then have rates of alcohol consumption been higher. The pattern of drinking in contemporary American society is thus one of moderate drinking rather than either abstention or excessive use.

Abstinence as Deviant Behavior

The general decrease in alcohol use and increase in number of consumers has been most clearly revealed since Prohibition, although it would be gratuitous to ascribe its cause to Prohibition alone. The implications of this pattern for the legitimacy of total abstinence are great. The object of change for the Temperance movement has been the act of drinking in any quantity. Any pattern of drinking, even though moderate, violates Temperance norms. The decline in the social status of WCTU women reflects a decline in the status of the Temperance norms. Not only have the Wet forces achieved political supremacy but now the Protestant middle classes have come to define abstinence as a deviant set of norms. As one informant put it: "There has been a breakdown in the middle classes. The upper classes have always used liquor. The lower classes have always used liquor. Now the middle class has taken it over. The thing is slopping over from both sides."

Within the adherents of the Temperance movement there is a clear perception that abstinence is not a recognized and respected position, that abstinent behavior is no longer a symbol of prestige-fui social position. There is a realization of the increased dominance of new middle-class norms in which the abstainer appears as an object of ridicule, contempt, and inferior status. One of the leading Temperance writers, Albion Roy King, has expressed the changed value of abstinence as a symbol of status:

There was a time when the rural pattern dominated the colleges, especially in the West. . . . Parents who have migrated from farming to urban vocations, with some nostalgia, still send the children to the rural colleges. But if they have climbed the ladder to a $10,000 a year status it is fairly certain that they have turned their backs on the rural mores and nothing symbolizes this more dramatically than the cocktail bar in the home."

The crisis for the abstainer is a crisis of legitimacy, Before Prohibition the status of the drinker was clear. He was at best a tolerated person within the circles of respectability which made up the reference groups of the abstainer. The people who thoroughly rejected Temperance norms were below him in social class or so far above him and so few as to be relatively unimportant for his sense of status in his community. The upper-class culture in which drinking was wholly accepted was a cosmopolitan one, not to be found in the small towns and rural areas. The lower-class culture in which drinking was unambiguously accepted was outside the pale of the abstainer's society—the ne'er-do-wells of his town or the foreigners of the big cities. This is no longer true and the change threatens to reverse the position of abstainer and drinker. It is the norms of abstinence which, increasingly, lack social dominance and are less and less legitimate in the middle class than was the case a generation ago. It is bitter for the abstainer to taste the truth of the advertiser's assertion that "Beer belongs."

In the nineteenth century an attitude of contempt toward alcohol was a positive sign of membership in respectable, middle-class life. In the mid-twentieth century an acceptance of pleasant vices on a moderate scale is a mark of the tolerance and fellowship in which leisure and comfort are prized. As drinking becomes a sign of membership in the upper middle classes, even the churchgoer is less steadfast in support of the legitimacy of abstinence. Not only are official church pronouncements less severe in their denunciation of drinking, but the ministry is seen as more protective and less condemnatory of the member who drinks. The abstainer feels less sure that his usual circles of church, family, and neighborhood support his own belief. ". . . drinking has become so prevalent that one who would cry out against it is regarded as a fanatic." 45

The ambiguity of Temperance as the legitimate doctrine of Protestant, native, middle-class society is reflected in the failure of the Temperance advocate to associate abstinence with people of prestige and the act of drinking with lowered prestige. Moderation is the prevailing norm which young people are likely to meet in school and in church, as well as in the mass communications media. "The greatest difficulty to be found today among youth, in anti-alcohol education, is the fact that 'good people' are using liquor." 46

The crisis stems from the openness with which drinking occurs, the acceptance of the pattern of moderation rather than abstinence, and the ambiguous, even deviant position of the abstainer in relation to figures of prestige in his own local communities as well as in the larger national society. It is less a matter of the statistical regularity with which abstinence is followed than its symbolic import in fixing and validating social status.

Actually, there is little indication that less people uphold abstaining sentiments than they did shortly after Repeal. For the past 20 years, the Gallup Poll has consistently shown that about one-third to two-fifths of the American adult public claim that they are abstainers.47 If there has been any change, it has been seen in a slight increase in the proportion of those claiming to be abstainers. Temperance sentiment, as indicated by political activity, has changed remarkably little since 1939. In that year 18.3 per cent of the American population lived in areas that had voted to become Dry. In 1959 the percentage had declined to only 14.1 per cent.48

Abstinence is less prestigeful than it was a generation ago. The college-educated male and female have shown greater change toward increased drinking than any other proportion of the American population." The public acceptance of the moderate drinldng pattern as prestigeful is the backdrop to contemporary Temperance sentiments. As one writer complains, in discussing the use of liquor at weddings of church people, "Liquor is safely and securely in . . . because so many of the very best people of the community are not refusing it." 50

Moral Indignation and Dominant Renegadism

The relation of the Protestant, upper middle-class moderate drinker to the Temperance movement is much like that of the renegade to the troops in which he was once a soldier. He has turned his back on their rules and committed an act of disloyalty. The moderate drinker has disavowed Temperance norms and has expressed his disaffection for the rules which once were standard guides to his action. From the standpoint of the total abstainer, this moderate drinker is a traitor to his status group. He has taken on the norms of the enemy.

There is, of course, one major difference between the renegade and the middle-class, moderate drinker. The drinker has succeeded in universalizing his renegadism. He has not gone from one camp to another. Instead his action has become the new standard and those from whom he defects are now the aberrant followers of a past doctrine. His rebellion has succeeded. The similarity to renegadism, however, lies in the defection from a previously fixed standard. The Catholic, urban, immigrant could not be expected to live up to norms of what is to him an alien culture. The middle-class moderate drinker could be expected to do so.

The renegade is often a figure of greater hostility than is the member of the deviant or culturally opposing group. ". . . the behavior of the repudiated membership group toward the former member tends to be more hostile and bitter than that directed toward people who have always been members of an out-group." 51

In the case of the attack on the legitimacy of Temperance norms the threat to the normative system and the status of the abstainer is even greater than in simpler instances of renegadism. The moderate drinker not only represents the fear that his example may be catching. His prestige and his behavior are actually diminishing the value of abstinence in the hierarchy of actions by which prestige can be increased or maintained. Furthermore, the prestige-deflating action occurs at the hands of people from whom the abstainer had greater expectations. They have let him down.

These considerations help us to understand both the bitterness and indignation of the Temperance movement toward moderate drinking and the concentration which the movement has shown since Repeal on the moderate drinker as the focus of reform. As the object of the movement's concern and anger is no longer socially subordinate, assimilative reform has very greatly diminished. The hostility, bitterness, and aggression of the movement is less that of Protestant-Catholic, urban-rural, or foreign-American conflict than it was before and during Prohibition. Both of these past strains exist. They are overshadowed by conflicts of an internal nature and of indignation directed at the defectors from the past standards. These are the people who are most responsible for the decline of the status of the abstainer and the rejection of Temperance as a legitimate and dominant system of behavior.

An illustration of the indignant response can be seen in one of the many similar stories in Temperance journals since Repeal in which the source of Temperance alienation is within the ingroup of one's fellow church members. In this story, "Today's Daughter," a 16-year-old girl goes to a party at the home of a new boy whose family has just moved into the neighborhood. Aunt Liz is suspicious when the boy tells Ruth's family that his new house has a game room in the basement. She knows that many of the new houses in the area now have bars in the game room. Ruth's mother tries to calm her sister's fears by telling her that this family is "alright. They joined the church last Sunday." Aunt Liz's reply upsets the mother and expresses the indignation of the Temperance advocate at the changed culture in which he now lives: "As if that meant respectability these days! Many's the church member who drinks and smokes and thinks nothing about it." 52

Temperance, in this aspect of its doctrine, becomes a censure of the new habits of middle-class Americans. Wherever he looks the abstainer finds his expectations of respect for Temperance norms contradicted by the new doctrines of socially acceptable moderation. The Temperance advocate becomes the upholder of the past to this segment of the middle class, rather than the enunciator and defender of its norms at the level of moral ideals.

A great deal of Temperance denunciation is of moderate drinking and of the role of social acceptance in middle-class circles. A suburban woman, local officer in her WCTU, was typical of those we talked to in holding the churches partly responsible for the decline in Temperance morality. "The churches aren't helping some of them. We went to the home of a professor for a church meeting and his wife served sherry."

In terms of activities this has meant a great concentration on issues of church acceptance, of testimonials from prestigeful people, and on counteracting the implications of the fashionableness of drinking. The National Temperance League has even condemned the fashion of "cocktail gowns" because it establishes and supports the status symbol of drinking as prestigeful.53 Great attention has been given to maintenance of restrictions against liquor and beer advertising and on establishing the validity of social dissent, that is, the ability of the person to say "No" when offered a drink." In all these ways the abstainer has concentrated on convincing his own membership groups to accept him even though he is an abstainer and to reaffirm their own past norms. Perhaps nothing illustrates better the need for the movement to again identify its norms as dominant than the slogan which the WCTU tried to popularize in the middle 1950's—"It's Smart Not to Drink."

The embittered sense of rejection and antipathy to the defectors from the Temperance standards represent a decided change from past tendencies to place Temperance in a context of religious and ethnic conflict. The wrath of the abstainer is now placed in a cultural conflict, divorced, to a large extent, from this framework and implicated in another conflict in which the declining status has new political consequences. In discussing these in the next chapter, we must keep in mind the decline in the norms and values of Temperance which has generated the specific direction of contemporary Temperance hostility. The position of the abstainer and of abstinence in the status hierarchy is not as significant as the sense of loss from a past place of legitimacy in the middle class and dominance in the society. A woman in upstate New York gave us an intellectualized statement of this sense of status decline: "We were once an accepted group. The leading people would be members. Not exactly the leading people, but upper-middle class people and sometimes the leaders. Today they'd be ashamed to belong to the WCTU. . . . Today it's kind of lower-bourgeois. It's not fashionable any longer to belong."

1 Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 5th ed., p. 510.

2 Emile Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society, tr. George Simpson (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1947), p. 96.

3 Svend Ranulf, Moral Indignation and Middle Class Psychology (Copenhagen: Levin and Munksgaard, 1938), p. 1.

4 Max Scheler, L'Homme du Ressentiment, tr. unknown (Paris: Gallimard, n.d. ), p. 14. The original was published in German in 1912. As Scheler acknowledges, the idea was developed in an earlier form by Nietzsche in his The Geneology of Morals.

5 Robert K. Merton's discussion of "disinterested" reaction to norm-violation was mentioned above ( Chapter 3, p. 61 ) and is found in Social Theory and Social Structure, rev. ed. (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1957), pp. 357-368.

6 Durkheim, op. cit., p. 103.

7 Ranulf, op. cit., p. 200.

8 Merton, op. cit., p. 156.

9 Robin Williams, American Society (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1960), p. 374.

10 J. Milton Yinger has analyzed a wide range of such subgroups in his "Culture, Subculture, and Contraculture," American Sociological Review, 25 (October, 1960), 625-635.

11 Williams, op. cit., pp. 372-396.

12 Ibid., p. 375.

13 Scheler, op. cit., pp. 42-45.

14 Charles Merz, The Dry Decade (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran and Co., 1937), p. 22.

15 Almost every historical account of the 1920's makes this point. For an account of drinking during this period which is consistent, even though heavily favorable to Prohibition, read Preston Slosson, The Great Crusade and After, 1914-1928, Vol. 12 in Arthur Schlesinger and Dixon Ryan Fox (eds.), A History of American Life (New York: Macmillan, 1931), Ch. 4. We have found no convincing data which could give any accurate estimate of the amount of drinking which occurred during the Prohibition years. On the basis of Jellinek's evidence and reasoning, cited and discussed below, it would seem most accurate to say that during the Prohibition era less alcohol was consumed by the nation than was consumed in the 14 years before or after. This provides no statement about quantitative drop nor does it answer questions about drinking in those areas where Prohibition was most strongly resisted.

16 E. M. Jellinek, "Recent Trends in Alcoholism and in Alcohol Consumption," Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 8 ( July, 1947), 1-43, at 9.

17 The Union Signal (March 5, 1927), p. 5.

18 Merz, op. cit., Chs. 3, 6.

19 Peter Odegard, Pressure Politics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1928); Justin Steward, Dry Boss (New York: F. H. Revell Co., 1928), Ch. 9.

20 Merz, op. cit., p. 129.

21 Ibid., p. 82.

22 See the account of developing Catholic voting power at the 1924 Democratic convention in Samuel Lubell, The Future of American Politics (New York: Doubleday and Co., Inc., 1958).

23 Typical of this material are Fletcher Dobyns, The Amazing Story of Repeal (Chicago: Willett, Clark, and Co., 1940), and Ernest Gordon, The Wrecking of the 18th Amendment (Francestown, N.H.: The Alcohol Information Press, 1943).

24 Murray Edelman, "Symbols and Political Quiescence," American Political Science Review, 54 (September, 1960), 695-704.

25 Virginius Dabney, Dry Messiah (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1949), p. 136.

26 Hearings of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 65th Congress, 2nd and 3rd Sessions, Brewing and Liquor Interests and German Propaganda (1919).

27 Annual Report of the NWCTU (1919), p. 68.

28 Ibid. ( 1929), p. 73.

29 The Union Signal (December 15, 1928), p. 12.

30 Anti-Saloon League Yearbook, 1931 (Westerville, Ohio: American Issue Publishing Co., 1931), p. 9.

31 William F. Whyte, Street-Corner Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1943), Ch. 4; Daniel Bell, "Crime as an American Way of Life," in his The End of Ideology (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1960), Ch. 7.

32 See the Hearings of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 69th Congress, 1st Session, Bins to Amend the National Prohibition Act (1926).

33 See the Hearings of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 71st Congress, 2nd Session, On the Prohibition Amendment (1930), and the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 72nd Congress, 1st Session, Modification or Repeal of National Prohibition (1932). Unions had appeared in opposition to Prohibition at the 1926 hearings but in the 1930's there were many more and they used economic rather than ethical arguments.

34 In North Carolina, for instance, the manufacturers proved strong supporters of state Prohibition. Daniel Whitener, Prohibition in North Carolina, James Sprint Studies in History and Political Science, 27 ( 1945), p. 155. The argument of an efficient work force was always of some importance in Temperance, although seldom dominant. Irenee DuPont had used it when he had championed the Prohibition Amendment.

35 Dabney, op. cit., pp. 210-211.

36 Cited in Paul Carter, Decline and Revival of the Social Gospel: Social and Political Liberalism in American Protestant Churches, 1920-1940 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1956), p. 129.

37 Annual Report of the NWCTU (1915), p. 93.

38 Jellinek, op. cit., p. 30.

39 Anti-Saloon League Yearbook, 1911, P. 30.

40 Annual Report of the Distilled Spirits Institute (1940), Appendix E.

41 Arthur W. Anderson, "Is There a Positive Equivalent to Drink?" The Union Signal (December 14, 1957), p. 10.

42 Based on data compiled by Mark Keller and Vera Efron, Selected Statistics on Alcoholic Beverages (1850-1957) and on Alcoholism (1910-1956) (New Haven, Conn.: Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 1958).

43 Jellinek, op. cit., p. 9.

44 Albion Roy King, "Drinking and College Discipline," Christian Century (July 25, 1951), pp. 864-866.

45 The Union Signal (February 21, 1953), p. 9.

46 Roy L. Smith, Young Mothers Must Enlist (Evanston, NWCTU Publishing House, 1953), P. 3.

47 In 1945 67 per cent of the national sample said they were users of alcohol; in 1950 it was 60 per cent; in 1958 it was 55 per cent. News release of March 5, 1958, American Institute of Public Opinion, Princeton, N.J. While the precision of the Gallup Poll is open to much debate, an estimate of 30-40 per cent abstainers appears reasonable since it is also supported by other studies during the past 15 years. Riley and Marden found 35 per cent of a national sample were abstainers in 1947. John W. Riley, Jr., and Charles F. Marden, "The Social Pattern of Alcoholic Drinking," Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 8 (September, 1947), 265-273. Maxwell found approximately 37 per cent of a Washington state sample were abstainers in 1951. Milton Maxwell, "Drinking Behavior in the State of Washington," ibid., 13 ( June, 1952), 219-239. Mulford and Miller found 40 per cent abstained in their 1958 sample of Iowa residents. Harold Mulford and Donald Miller, "Drinking in Iowa," ibid., 20 (December, 1959), 704-726.

48 Annual Reports of the Distilled Spirits Institute for 1939 and 1959.

49 See Mulford and Miller, op. cit., p. 72. Gallup has found the same trend. As college becomes a source of cosmopolitan values it widens the population among whom drinking is respectable. See my "Structural Context of College Drinking," Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 22 (September, 1961), pp. 428-443.

50 The Union Signal (October 18, 1952), p. 8.

51 Robert Merton, op. cit., p. 296.

52 The Union Signal (December 25, 1937), pp. 5-6.

53 "Cigarettes and fashion, cocktail hours and cocktail dresses, tie women into drinking . . . the pressure of cocktail fashions on women has subtly led them to feel that ours is a cocktail culture." "Women Now, Children Next?" The American Issue, 67 (June, 1960), p. 4.

54 In 1959 the WCTU organized a Committee on Social Freedom to help develop norms of hospitality which would enable abstainers to take part in many social activities. The pamphlets and reports of this committee remind hostesses to present guests with the option of fruit juices, as well as alcohol. Here, again, is clear recognition of the decline in the social dominance of Temperance within the social circles constituting their own membership groups.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|