4 Coercive Reform and Cultural Conflict

| Books - Symbolic Crusade |

Drug Abuse

4 Coercive Reform and Cultural Conflict

The coercive reformer does not perceive the subjects of his reform with sympathy or warmth. They are not victims who can be as-similated into his communities or converted to his culture. Coercive reform is a reaction to a sense of declining dominance. The violators of norms are now enemies, who have repudiated the validity of the reformer's culture. They are beyond repentance or redemption. Coercive reform is nurtured by a context in which groups hold con-trasting norms. In this context each group challenges the power and prestige of the other. The coercive reformer has begun to feel that his norms may not be as respected as he has thought. He is less at home and somewhat more alien to his own society.

There is a similarity between the orientation of political radicalism and the orientation of coercive moral reform. Both stem from a polarized society in which the radical and the coercive reformer are both alienated from social and political dominance. Bx polariza-ion we mean a process in which groups within the society are sharply separated from each other. They hold different values, live-in different areas, are affiliated- with diferent organizations, and hold different political orientationi:There is Iiitle cross membership. As a result the lines of group differentiation are clearly drawn. Cultural polarization refers to the process in which culfural groups—ethnic conununities, religious groups, status groups of other kinds—are sharply separated. Polarization implies a situation of conflict rather than one of dominant and subordinated groups. In a polarized so-ciety there is little middle ground. Each class or status group feels alien to the other. In this sense, the radical, like the coercive reformer, cannot see his problems solvable within the frame of exist-ent institutions. The middle ground of common agreement or of accepted domination between political or economic groups has dis-appeared. Both types are in a critical posture toward the existent situation.

These orientations of both political radicalism and coercive re-form existed in the Temperance movement during the late nine-teenth century in both the WCTU and in the Prohibitionist wing of the movement. The politically radical elements in Temperance con-tributed to the growing polarization of cultural forces in the United States which culminated in the drive for constitutional Prohibition. That drive for political enforcement was an attempt to defend the position of social superiority which had been stabilized during the nineteenth century but was threatened during the first two decades of the twentieth.

SOCIAL CRITICISM IN THE WCTU

The WCTU demonstrated its criticism of American institutions in two major aspects of its activities and program in the late nine-teenth century: in its support of the Feminist movement and in Frances Willard's attempt to ally the organization to the Populist Party and to Christian Socialism.

The Feminist Movement and the WCTU

An affinity between Temperance and the movement for female equality was evident even before the Civil War. Most of the great figures in the history of the Woman's movement were active in the Temperance movement,' at some time or other. It was one of the few organizational activities open to women in the mid-1800's. The formation of the WCTU was in itself an important event in the history of women in the United States. During the winter of 1873-74 church women in Ohio and other Midwestern states led a "crusade" into saloons, praying and pleading for their closing. Such conduct was shocicing by the rules of middle-class female conduct of the time. The direct action by women, and the subsequent formation of the WCTU as a result of it, was a unique activity for the women of the 1870's.2

Despite the feminist significance of its origins, neither Feminism nor the more radical Suffrage movement received immediate sup-port from the WCTU. Suffrage carried the onus of secularism and sexual immorality. The conservative forces of the WCTU were deeply against any action which might suggest WCTU approval of Suffrage. The progressive wing of the organization was deeply committed to working for Suffrage. Frances Willard's ascent to the presidency in 1879 settled the issue in favor of the drive for the women's vote. The issue was so intense a matter that continued WCTU support of Suffrage led to the resignation of Mrs. Witten-myer and her followers from the organization.

Frances Willard became one of the leading figures in the Feminist movement and in the Suffrage organization, the Woman's Party. Both during her administration and later, the WCTU was active in a number of movements which attempted to gain greater equality for women. Many of its conservative activities were oriented toward the demands of Feminism. In prison reform work, for example, the WCTU led a move to hire policewomen and to segregate male and female prisoners. It championed the appearance of women as dele-gates to ecclesiastical conferences and as ministers. Even in an at-tack on prostitution and in its aid to destitute women there was a harsh criticism of men and the double standard of morality which allowed the client to go free.' Since drinking had been largely a male activity, the concern of the woman for Temperance was itself an act of controlling the relations between the sexes.

The support the WCTU gave to the Woman's movement had two important consequences. It established a critical posture toward the status quo and it identified the organization as one dedicated to progress and the future, rather than upholding traditions of the past. In both ways it increased the sense of opposition to the status quo. The present relations between men and women, so went the argument, were enslaving. The future would be less oppressive. Dress reform and physical exercise were turned into symbolic acts of rebellion and liberation. With their multiple folds of undergar-ments and with the use of tight corsets, the female fashions of the 1880's and 1890's made work and movement difficult.4 Taboos of modesty made it immoral to dress in ways which enabled the woman to exercise. The WCTU offered prizes for the design of freer garments and its journals carried advertisements for dress reform shops and for less restrictive corsets.5 A Department of Physical Culture was formed and young Temperance women dem-onstrated the use of the dumbbell at WCTU conventions. Frances Willard, with her characteristic flamboyance, did the daring thing of riding a bicycle in public and then wrote a book about it!' There was even a move to persuade the women of the WCTU to use their first names in formal address even though they were married. "We dislike," wrote a Union Signal editor, "to see the good wives losing their identity and individuality." 7

These actions were a step away from the customs of the day. They not only provided one anchor of critical orientation toward the pre-vailing social patterns, but also bolstered the identification of Tem-perance itself with a favorable attitude to change. Whatever was new, modern, and part of the future carried a ring of acceptance with it. Speakers were eulogistic in referring to the WCTU as "radical" and derogatory in calling opponents "conservative." 8 The posture of radicalism was, in the WCTU, allied to an optimistic sense of growing success. "Caterers should look forward and not backward," wrote a WCTU editor in criticizing the use of alcohol at a public affair.°

Political Radicalism and the WCTU

Under the leadership of Frances Willard, a determined attempt was made to ally the WCTU to a wide range of radical movements. Woman's suffrage was only one of the unpopular causes which gained Miss Willard's attention. While it was an unsuccessful at-tempt, it had two effects upon the organization: (1) it laid the basis for the critical attitude toward American institutions which united the Populistic and the more conservative wings of the move-ment in the Prohibition campaigns of the early twentieth century, and (2) it united political forces of conservatism, progressivism, and radicalism in the same movement.

Criticism of American Institutions

Before the late 1880's, Willard's speeches were characterized by a general tone of assimilative welfare, couched in a concern for the underdog and the underprivileged,During the 1880's, however, she was deeply influenced by the criticism of the capitalistic industrial economy expressed in agrarian and Christian Socialism. During visits to England and the Temperance leaders there she had formed a number of friendships among the British Fabians. She was an as-sociate editor of the American journal of the Society of Christian Socialists, to which she frequently contributed.°

These associations led her to try to commit the WCTU to a pro-gram of radical economic and political reconstruction. The program which she advocated was one version of the then common Socialist proposals to utilize government as the vehicle of economic, justice and moral reform. In speeches to the WCTU national conventions she demanded the triumph of Christ's law and the abolition of competition in industry; a minimum wage for labor and an equivalent of a guaranteed wage; collective ownership of the means of production; public ownership of newspapers as a way to end ob-scenity; and the nationalization of amusements as a way to insure standards of decency» She was all for ending the rule of "Capital-ists in control." Henry George and the Single Tax, Samuel Gompers and the Universal Federation of Labor, Sidney Webb and the Fabians, Keir Hardie and Tom Mann were all subjects of her great approval. She told audiences that in some future day humanity will declare itself one huge monopoly, the New Testament will be the basis for regulating human behavior, and "all men's weal is made each man's care by the very constructicm of society and the consti-tution of government." 12

This explicit support for the tenets of Christian Socialism con-tradicted the ameliorative conservative and progressive strands in the movement. Although it was still an assimilative perspective, marked by sympathy toward the urban, immigrant worker, it placed Temperance in a framework of multiple social problems, rather than visualizing it as the cornerstone of all social reform. In placing her stress on institutional reforms of a wide character, Willard implied that Temperance was itself a consequence of the economic and so-cial structure. An immoral society produced immoral people. In her addresses between 1892 and 1898 she was quite clear that individual moral imperfection was not the root of social evils. It was institu-tions that brought about imperfect human beings. Crime and prosti-tution, she declared, are not only matters of human choice; they are also matters of the low wages paid to men and women. She took a most heretical step for the advocate of Temperance; she main-tained that intemperance is itself a result of social conditions: "We are coming to the conclusion—at least I am—that we have not as-signed to poverty at one end of the social scale and idleness at the other those places of prominence in the enumeration of the causes of intemperance to which they are entitled." 13

Willard's views were never the "ofBciar doctrine of the WCTU or of any other Temperance organization. Some members were shocked by her Socialism. For many reasons, as well as ideology, there was a brief movement to unseat her. Nevertheless Willard's radicalism succeeded in drawing into the WCTU many women who were attracted by its identification with the new and the daring." She was moderately successful in developing a Department of the Relation of Temperance to Labor and Capital which sought to aid the development of the Labor movement.

Union of Conservative, Progressive, and Radical Christianity

VVhat is so outstanding about the WCTU in this period (1870-1900) is the union of the diverse strands in social Christianity. Populists and anti-Populists, Suffragists and non-Suffragists, pro-Labor and anti-Labor views were all represented in the WCTU."

Despite the generally Republican support which Temperance people displayed in national politics, the WCTU did develop back-ing for Prohibitionist candidates. Although legislative measures were not as dominant as education in their arsenal of weapons against alcohol, the organization did provide an audience for Pro-hibitionist speakers and a source of actual workers in local and state campaigns. In 1884 Willard even claimed that the Prohibition-ists, and with them the WCTU, were responsible for the balance of power. By withholding potential Blaine votes they permitted Cleve-land to become President.16

During the 1890's Willard also tried to forge an alliance with the Populist Party, especially in its formative stage. She was chairman of the first Populist Party convention. During the campaigns of 1892 and 1894 she used the WCTU committee system as a device for gathering Populist petition names. This attempt to place the WCTU in the orbit of sponsors of Populism failed, partly because the urban orientation of the organization was indifferent to the rural problems of Populism and partly because the Populists were unwilling to risk the loss of immigrant votes which Temperance support would have endangered.

Relationships to political radicalism were merely one element in the WCTU. They were an important part of the total Temperance movement and make up the ideological and social basis of the coer-cive strain in Temperance.

POPULISM AND COERCIVE TEMPERANCE REFORM

All forms of radicalism have at least one element in common: they are united by their critical posture toward the existing social order. Whether they are trying to resurrect an earlier form or to fashion a new plan, radical movements see the present as distasteful and preach the necessity of deep and fundamental changes. It is just this lack of identification with present social and political domi-nance which marks the coercive strain in Temperance doctrine. The Populist component in Temperance contributed to coercive reform in two respects. It provided a general expression of alienation from the urban and industrial culture and it directed attention toward the institutions of business as targets of reform. Its orientation to social problems was clearly not assimilative. The goal of Temper-ance through direct prohibition of sales was more in common with Populism and radical social Christianity than it was with conserva-tive and progressive reforms.

Agrarianism and Temperance

Some historians have suggested that the Prohibition Party of the nineteenth century was one arm of the leftist movements elsewhere manifested by the Greenbackers, the Non-Partisan League, the Populist Party, and the agrarian elements of the Socialist Party.17 There is some truth in this assertion but it must be carefully qualified.

The emergence of an organized political party dedicated to na-tional Prohibition occurred in 1869, in response to the reawakened Temperance movement which produced the WCTU. The 1872 and 1876 platforms of the Prohibition Party read like many manifestoes of the agrarian radicalism of the time. The Prohibitionists advocated a federal income tax, woman's suffrage, the regulation of railroad rates, the direct election of United States senators, free schools, and an inflationary monetary policy.18 Their platforms also contained planks which advocated the use of the Bible in public schools and the national observance of restrictions on Sunday business and amusements. The economic and political measures were similar to those of the Greenbackers and the National Grange. They were the sentiments of farmers who saw themselves oppressed by urban financial institutions, manufacturing interests, and the political machines.

We would be misled, however, if we interpreted Temperance as a log,ical outcome of agrarian economic discontents. The union be-tween Populistic, agrarian sentiment and Prohibitionist doctrine was more adventitious than that. During the 1880's, when the state Dry campaigns were most intense and agrarian movements less strildng, these planks were dropped from the Prohibitionist plat-forms or replaced by general statements of an antimonopolist na-ture. In 1892, in the wave of Populist state elections, the platform again reflected agrarian economic ideas. In 1896 we would have expected the most forceful statement of Populist sentiments, both because such sentiments were at their height and because they would have been politically necessary to counteract the appeals of the Bryanites. Indeed, within the party the 'broad gaugers" sought just such a platform. They were defeated by the "narrow gaugers," who restricted the party to the single issue of Prohibition.19 At no time from 1872 to 1896 were non-Prohibition issues given much attention in the speeches of the Prohibitionist leaders.

The platform inclusions and exclusions of the Prohibition Party suggest that party leaders saw Populist territory as a major center of Prohibitionist support. They felt it necessary to counteract the possible appeals of other third parties and of the major parties to the economic and political interests of this social base. These were neither dominant nor significant appeals to Prohibitionists, however. There was no concern with the range of urban social problems which we have encountered in the WCTU. Labor, for example, was treated in very general terms or exhorted to follow abstinent standards.2° While Prohibition was not a part of the economic and political response of the farmer to his conflicts with industrialism, it did have a special appeal to the rural segment of the population, where Populist sentiments were also strong.

Agrarian discontent was at its height in the same parts of society where Prohibition made its greatest state gains in the 1880's—Kansas, Iowa, and Ohio. The Grange lent active support to the Woman's crusades in 1874 and often helped the wen]. in its local and state campaigns for liquor restrictions. At the state levels, the Populist Party often included Prohibition as one of its aims, al-though it balked at including it in the national platform. The im-migrant vote was considered too important to be alienated. The affinity between Prohibitionist sentiment and Populist support was close enough so that a delegate to the People's convention in 1892 could remark that a "logical Populist" was one who had been a Granger, then successively a Greenbacker, a Prohibitionist, and a Populist.2'

The Prohibitionist appeal was not based on any effort to convert the sufferers, as was the conversionist doctrine of the WCTU. Pro-hibition, both in the usage of the party and as an element in the other Temperance organizations, assumed that its views represented moral righteousness and that the drinkers could not be con-verted by means other than legislation and force. It is just this that Prohibition had in common with Populism. Both movements were nourished by a sense of conflict with the urban, industrial com-munities of the United States. VVhat Populism contributed to the Prohibitionist spirit was the confrontation of one part of the society with another. On one side were the manufacturer, the banker, the director of railroads, with their urban culture from which homey virtues of church and family were absent. On the other side were the farmer and the small-town businessman, in debt to the monopo-lies of transport, finance, and manufacture but committed to the culture of Protestant, temperate America. In this cultural confronta-tion, unlike the urban progressivism of the WCTU, the native American, Protestant, sober man was the underdog. The assimilative appeal tried to redeem the urban alienated. The coercive appeal was an attempt of the alienated rural population to strike back against the urban powers.

Prohibition and the Rhetoric of Alienation

What this contributed to the coercive strain in Temperance was a sense of economic and political powerlessness which formed the ideological justification for Prohibitionist doctrine. Richard Hof-stadter has detailed the manner in which Populist appeals were based on a theory of conspiracy.22 That theory held that evil men of the commercial cities of the East manipulated currency, tariffs, and national policy for their selfish advantage. Politics, too, was suspect as the area in which the monopolist bribed legislatures and rigged elections. The "people" were cheated and preyed upon by the business interests that rendered them powerless to use their constitutionally developed political institutions. The primary, the referenda, and the direct election of senators were devices to re-turn government to "the people."

This bridge between Populist and Prohibitionist ideology is crucial for the later development of the Prohibitionist cause. In assimilative doctrines, the drinker is the subject of Temperance reform. He must be persuaded to take on Temperance habits. The Populist assumption of business malevolence is a very different point of view with distinct consequences. It leads quite easily to the assertion that institutional forces of the business quest for profits are at the root of intemperance. It was logical to link to-gether, as Prohibition orators did, the forces of "grogshops and monopolies" as the prime enemies of total abstinence.

Populist sentiment and rhetoric made it easy to focus attention on the liquor industry as the dominant cause of drinkinz. The lead-ing Prohibitionists of the 1880's manifested a Populist commitment. John B. Finch called his collected speeches The People versus the Liquor Traffic. John P. St. John, 1884 presidential candidate of the Prohibition Party, was the former Populist governor of Kansas. Both men spoke of the enemies of Temperance largely as "the organized liquor interests." 23

If the liquor "trusts" were opposed to Temperance, it was diffi-cult to see that anything short of coercion could appeal to them to stop their immoral trade. The liquor lords were seen as absolute political autocrats who tried to dictate the nominations of both Democratic and Republican parties. This sense of malevolence and power put the liquor interests outside the moral norms through which men might persuade each other, and outside the middle-class appeals to social mobility by which the dominant might im-press the subjugated.

The coercive strain in Temperance orientations was thus a re-sponse to cultural confrontations which took place in an atmosphere of conflict and threatened alienation. As the economic and political dominance of agrarian society was undermined by the urban, in-dustrial capitalism of the late nineteenth century, the cultural differentiation between rural and urban, native and inunigrant, sacred and secular was given an added dimension of meaning. The failure of Temperance forces to have brought about a sober, temperate, and well-behaved society was more than the failure of a dominant culture to have implanted its style of life as the ruling style. It was tantamount to the failure of that culture to continue as the dominant source of values.

Nevertheless the Temperance issue remained in the orbit of a general stream of conservative, progressive, and radical movements expressive of dominance or alienation in the American social struc-ture. Only as the cultural confrontations widened and the eco-nomic struggle lost some of its politically separating tendencies did Prohibition emerge as a vital and politically dominant issue.

POLARIZATION AND THE PROHIBITION CAMPAIGNS

By the tum of the century Temperance was a movement which combined both assimilative and coercive appeals within and among the various wings. Because of this mix of appeals and subsidiary movements Temperance had a pluralistic rather than a super-imposed following. These terms—pluralistic and superimposed—refer to the degree of political diversity and isolation which char-acterize social groups. Groups that differ in political outlook on almost all questions with little overlapping are in a posture of superimposition. The situation is pluralistic when the opposite is the case, when outlooks are not sharply related to group affiliation. When the rural, Protestant, native American is almost always in favor of Prohibition, and the urban, Catholic, immigrant almost always opposed, the situation is one of superimposition. Each ele-ment of group identity reinforces the other. The more an issue represents a constellation of superimposed social forces, the more likely is it that the issue becomes one of sharpened group loyalties and compromise is less feasible. In a pluralistic structure there is a middle ground, pulled in both directions by the competing forces. Under conditions of superimposition the political sides are more sharply polarized.

The campaign for national Prohibition had a polarizing effect on the Temperance movement. It maximized the cultural differ-ences between pro- and anti-Temperance forces while minimizing the class differences. In this fashion it promoted an atmosphere in which the meaning of Prohibition as a symbol of Protestant, mid-dle-class, rural supremacy was enhanced. This process was a necessary stage in the development of Prohibition as a test of the prestige of the old middle classes in a period of industrial growth, urban development, and Catholic immigration.

The polarizing effects of the campaign for national Prohibition were unwittingly expressed in an editorial of the Anti-Saloon League journal:24 "The liquor issue," wrote the editor of The American Issue, "is no longer one of 'wet' and 'dry' arguments. Henceforth it is to be a question of 'wet men' and 'dry men.' " In effect, the issue of Prohibition posed a question of cultural loyal-ties in explicit terms. Attack on the saloon, rather than the drinker, located the problem of drinlcing in contexts which accentuated the conflict of cultures represented by the divergent sides.

The formation of the Anti-Saloon League, in 1896, has a symbolic importance for the Temperance movement. Tactically, the organ-ization led the fight to gain state and national Prohibition. Sym-bolically, the very title of the League suggests the movement away from the assimilative approaches of the WCTU or the political party approaches of the Prohibition Party. Both the singleness of purpose represented in the idea of the League and the sense of opposition suggested by the "anti" character of its name are dom-inant features of the Temperance movement in the period between 1900 and the passage of the Prohibition Amendment in 1920.

The saloon was pre-eminently an urban institution, a substitute for the less anonymous entertaining of the salon, from which it derived its name. For the small-town native American Protestant, it epitomized the social laabits of the immigrant population. To the follower of the Progressive movement, the saloon was a source of the corruption which he saw as the bane of political life. Accustomed to moralizing about politics, the Progressive reacted against the ethics of personal reciprocity on which machine poli-tics was built. Increasingly alienated from political power, the native American, urban middle class found a partial solution to its problems in the Progressive movement. It made conunon union with the already fixed alienation of the Populist. The growth of urban communities, so ran this argument, would wreck the Re-public. It would lead to the segregation of an element responsible for corruption, "which gathers its ideas of patriotism and citizen-ship from the low grog shop." 25

Within the context of Populist antipathy to urban and Catholic communities, the saloon appeared as the symbol of a culture which was alien to the ascetic character of American values. Anything which supported one culture necessarily threatened the other. "The Anglo-Saxon stock is the best improved, hardiest and fittest . . . if we are to preserve this nation and the Anglo-Saxon type we must abolish [saloons]." 26

Agrarian Sentiments and the Prohibition Drives

A new wave of Prohibition campaigns broke out in the United States after 1906. As a result of it, national Prohibition was achieved. During its spread, the rural nature of Temperance was enhanced and it becarne a dominant political issue, separated from the vvider net of movements current at the same time. The agrarian nature of the movement and the isolation of the movement from other political issues are major characteristics affecting its sym-bolic appearance.

Between 1843 and 1893, 15 states had passed legislation pro-hibiting statewide sale of intoxicants. Only in three states, Iowa, Kansas, and Maine, was Prohibition still in force. Between 1906 and 1912 seven states passed Prohibition laws. By 1919, before the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment, an additional 19 states had passed restxictive legislation, some through referenda. Most of these shifts into the Dry column had occurred by 1917, before the amendment seemed possible or probable in the near future."

The active work of the Anti-Saloon League and the Methodist Board of Morals of course had a great deal of influence on such victories. They did bring to bear the power and influence of the Protestant churches behind candidates and legislation of Dry aims. But the churches had long ago taken a staunch Temperance stand. Temperance sentiment had existed for a long time.

Several changes appeared in drinking habits during the first 20 years of the tvventieth century which reflected the decrease in the legitimacy and dominance of Temperance norms in the American society. For one thing, the consumption of alcohol was higher than at any time since 1850.28 After 1900 it began to rise and reached its peak in the period 1911-15. Also, the increase in consumption appears to have involved more persons as drinkers. The rise in alcohol consumption was accompanied by a decrease in consump-tion of distilled spirits but a large increase in beer drinking, a situation which suggests both a rise in moderate rather than ex-cessive drinking, and immigrant populations as a source of a large percentage of the rise.s°

That the cities were probably the source of much of the increase is also suggested by two other facts. First, local option appeared to have been evaded in the cities but in the small tovvns and rural areas it was well enforced.s° Second, despite the fact that by 1914 there were 14 Prohibitionist states, all predominantly rural, the national drinlcing rates, based on legal sales, were at their all-time high in 1915. A change was taking place in American drink-ing norms.

The rise of Prohibition strength owed a great deal to the sense of cultural change and prestige loss which accompanied both the defeat of the Populist movement and the increased urbanization and immigration of the early twentieth century. During the initial decade of the tvventieth century, the domination of American life, thought, and morality by the ethics of Protestant theology was waning. It was far from a period of serenity, despite the lack of the flamboyant issues of 1896. Assimilative tactics had not suc-ceeded in curtailing the drinlcing habits of the cultures nor in Nvinning assent to ascetic norms.31 The assimilative response made little sense when the dominant culture felt its dominance slipping away.

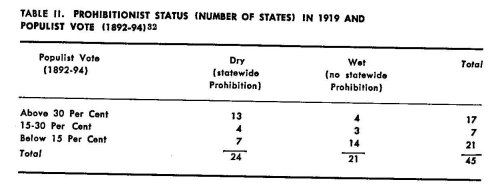

The radicalism of the coercive approach to drinlcing bears a remarkable resemblance to the geographical distribution of agrar-ian radicalism. Areas of the country which demonstrated state support for Populist candidates in the 1892 or 1894 elections were prone to adopt state Prohibition in the 1906-19 period. Table II provides the data to support this.

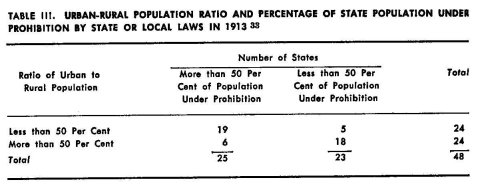

By no means do we imply that Prohibition is explainable as an extension of Populism. Both, however, express increased tension between parts of the social structure and between divergent cultures. The centralization of opposition to Prohibition within the Eastern, urban, states, where large percentages of Catholics and immigrants were to be found, is a fact which a great many ob-servers and analysts have noted. Major urban and industrial areas like Illinois, New York, and Pennsylvania were the last to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment. Table III indicates that there was a very close relation between rural status and Prohibitionist senti-ment. It shows that where the ratio of rural to urban population was high, the likelihood that the state had gone Prohibitionist in areas affecting more than 50 per cent of its population was also high. Rural states were more likely to support Prohibitionist senti-ment than were urban states.

The areas of national Prohibition sentiment were thus Protes-tant, rural, and nativist. They were more likely to be found in the South and the Midwest, although New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont were strong supporters of Prohibition. VVhile states with high percentages of foreign-born were likely to oppose Prohibi-tion, this was less true where the foreign population was Protes-tant and rural. In South Dakota, where 22 per cent of the popula-tion were foreign-born, 68 per cent lived under Dry conditions. In Illinois, where 20.1 per cent of the population were foreign-born, only 33 per cent were in Dry areas.84

More significant, perhaps, was the fact that within the individual state it was the urban areas that provided the greatest opposition to Dry laws. Here was the greatest source of votes against Dry legislation and for the repeal of such laws as did exist. Even in rural states, it was in the cities that the state or local laws were most often and openly evaded. In Alabama, where Prohibitionist sentiment was strong, the ten strong Wet counties were the dom-inant political, industrial, and financial centers of the state. The same was true in North Carolina and the other Southern states, where the Catholic population was small and the percentage of foreign-born almost niI.35

The polarization of population into distinct cultural and geo-graphical areas was a salient aspect of the Prohibition campaigns. The campaign for Prohibition in California is a striking example of polarities around which the issue was drawn. Here the cultural distinctions were formed around regional differences, to an even greater degree than was true of urban-rural differentiation. North-ern California was cosmopolitan, secular, Catholic, and Wet. Southern California was fundamentalist, Protestant, and provincial in its loyalty to the ideals of rural America. Although Los Angeles County was the second largest county in California in 1892, it polled approximately 14 per cent of its presidential vote for the Populist candidate (Weaver) and 4 per cent for the Prohibition-ist (Bidwell). At the same time, San Francisco County, largest in California, polled 5 per cent of its vote for the Populists and 1 per cent for the Prohibitionists. The state returns were below those of the Los Angeles vote: approximately 9 per cent for the Pop-ulists and 3 per cent for the Prohibitionists." The Populist cam-paign in California in 1894 displayed a marked Prohibitionist strain. 'This continued during the Anti-Saloon League and Pro-gressive campaigns of 1909-13.31 The League placed its organiza-tion at the use of the California Progressives. Temperance, nativ-ism, and Progressivism were linked. It was the North that repre-sented the greatest opposition to this triad, rather than the city per se. Southern California was Protestant and Progressive. "Los Angeles is overrun with militant moralists, connoisseurs of sin, experts on biological purity." 38 The saloon was identified as the major deterrent to the good government sought by the political reformers. In the Populist vein, it was against railroads and rail-road control that the Southern Californians directed their political animosities. In all these issues, the lines of political opposition were drawn along cultural attributes even though the urban-rural di-mension was subordinated. The North-South distinction had cul-tural as well as geographical implications.

The cultural distinction between Dry and Wet areas was even revealed in the period following Repeal in the South. In Alabama, South Carolina, and Mississippi in the 1930's the Dry vote was strongest in those areas which had been Populist in the late 1890's, were fundamentalist in religion, and where the farmholdings and the percentage of Negroes were sma11.89 It was not a simple urban-rural split that Prohibition touched off in these essentially rural states.

The polarities were also related to the cultural distinctions be-tween the plantation areas of the delta and the poor white farmer of the inland regions.4° Some writers have interpreted the rise of state Prohibition campaigns in the South after 1906 as an effort to control the Negro.41 Our interpretation is quite different. After 1900 whatever political power the Negro had had was broken by effective legal disenfranchisement.42 As long as the Negro had been anti-Prohibitionist and had voting influence, there was fear among Southern politicians that Prohibition questions were likely to bring about appeals by the Wets for Negro votes. It was the disenfranchisement of the Negro which made the political move-ment for Prohibition feasible in the South.

The Prohibitionists understood and were conscious of the conflict of cultures which both produced the issue and characterized the opponents. Dry men were native Americans; they were Prot-estants who took their religion with seriousness; they were the farmers, the small-town professionals; and their sons and daugh-ters, while they had migrated to the big city, kept alive the validity of their agrarian morals. Wet men were the newcomers to the United States; the populations that supported the political ma-chines of Boston, New York, and Chicago; the infidels and heathen who didn't keep the Sabbatarian laws of Protestantism; and the sophisticated Eastern "society people." All these were perpetuating and expanding the modes of life which the Dry had been taught to see as the mark of disrepute in his own local social structure. The outnumbering of the rural population by the urban, wrote an Anti-Saloon League editor, has been the cause of the wreckage of republics. "The vices of the cities have been the undoing of past empires and civilizations." "

The attack on the saloon emerged in urban areas as a link be-tween elements of Progressivism and the Temperance movement. It made it easier to depict Prohibition as a move toward good government and the end of political corruption. In the same fashion, nativism carried with it connotations of positive progressive re-form. It guaranteed the end of machine politics by limiting the power of groups who were felt to have no respect for American political principles. The sources of this reform were as much religious in origin as they were political. The California Voters League could declare that its objective was "a management of public offices worthy of an enlightened, progressive and Christian country." 44

Before the Prohibition drives of the early twentieth century, the Temperance movement had played an important role in local, state, and national politics. Often the Temperance vote had been a decisive balance of power. Neveitheless, state Prohibition was usually not enacted and usually repealed when it had been in force for several years. It is true that the organized movement led by the Anti-Saloon League and the Methodists was more efficient in rallying and focusing Temperance sentiment than previous organizations had been. It is true, however, that after 1906 Temperance forces in the United States made a more concerted political effort than they had ez9r done before, that this effort was largely the activity of rural populations, and that it occurred in a period when the United States was more urbanized than it had ever been. The strength and vibrancy of Temperance as a political force is the dominant attribute of the movement in the period between 1906 and the passage of the Prohibition Amendment.

The great movement toward national Prohibition was not the long-awaited outcropping of a slowly developing movement over 90 years of agitation. It was the result of a relatively short wave of political organization supported by the new enthusiasm of church members in the Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, and other evangelical" Protestant congregations. It is certainly true, as Vir-ginius Dabney has pointed out, that "when the movement for nation-wide Prohibition was approaching its climax in 1917, the political center of gravity of the country was not in New York or Chicago or San Francisco but in junction City and Smith's Store and Brown's Hollow." 45 But this was not a new feature of Ameri-can state politics. If anything it was changing as urban popula-tions grew larger by the addition of immigrants and rural migrants.

In striving to obtain Temperance by legislative controls of liquor and beer sales, one part of the American population was trying to coerce another part. The areas of the country where Temperance norms were most respected, where alcohol sales were most easily controlled, and where the Prohibition vote was strongest were demanding that the other areas be subject to the ways of life which were most legitimate to the total abstainer. The opponents of Pro-hibition were no longer sufferers to be helped but enemies to be conquered. "This battle is not a rose-water conflict. It is war—continued, relentless war." "

Another consequence of the movement toward political solu-tions to the drinldng problem was the isolation of the Temperance movement from other movements of reform. In the struggle to pass legislation, Temperance people devoted all their strength and perceived of most of their efforts as part of the political cam-paigns. Assimilationist reform diminished and past activities took on a political bent. For example, the work of the WCTU with laborers and with the Labor movement became single-mindedly oriented to gathering votes for the support of Prohibitionist measures. A 1909 committee report even argues that the alleviation of poverty is commendable because well-housed and well-fed people are more likely to vote for "civic righteousness" than are those of lesser wealth and comforts. The work of the WCTU lost much of its social welfare and religious evangelical character as the Pro-hibitionist cause dominated the Temperance movement. This move away from assimilative reform is strilcing when we consider that the Social Gospel movement gained in influence and importance in American churches during the first decade of the century.°

In this single-minded pursuit of legislative victories, the Tem-perance movement became isolated from other movements whose political and social doctrines Temperance people had supported in earlier periods. Woman's suffrage, Abolition, Labor, Populism, and even the Kindergarten movement were past lines of alliance which served to blunt the specific meaning of Temperance as a vehicle of cultural conflicts. Even the Prohibition Party, as we have seen, had to find a political ideology to which it tried to attach itself. The Anti-Saloon League, however, operated as a "pressure group," with no formal attachment to any political or social sys-tem of ideas other than evangelical Protestantism. The League followed the policy of "rewarding our friends and punishing our enemies." 48 Unlike the Temperance leaders of the nineteenth cen-tury, like Frances Willard, John St. John, and Lyman Beecher, the Anti-Saloon League officials had little past or later experiences with a wide gamut of reform activities or political programs.49

Neither did the linkage to Progressivism provide a major source of liaison between urban, nonnativist, and non-Populist groups and the spirit of coercive reform. For one thing, Prohibition was still largely rural, strongest in rural states, and couched in the language of Populist aggression against the city. While a number of Progressives were drawn into it, it was always an uneasy alli-ance between the urban, upper middle classes and the small-town farmer or businessman. Second, the elements of Progressivism which formed the appeal to the coercive side of Temperance were largely the hostile, antinativist aspects rather than the assimila-tionist elements of the progressive parts of social Christianity.5° In these assimilative aspects the immigrant was a victirn of a source of suffering. For the coercive reformer the liquor evil was sinful but it had to be attacked institutionally rather than individ-ually. This is the source of its radicalism. Here, for example, is a statement by Daniel Gandier, Director of the Anti-Saloon League in California and a staunch supporter of Hiram Johnson and the California Progressive movement. In 1910 he wrote:

The fight is just begun. The selfish forces of the landowner—Big busi-ness and its ally,' commercialized vice—are preparing for the death struggle. I believe the spirit of our age is against them. Everything which lives by injuring society, or which enriches the few at the expense of the many, is doomed to go. The spirit of brotherhood, which means a square deal for all and that those of superior cunning shall not be allowed to rob their less cunning fellows any more than the physically strong shall rob the weak, is abroad and is going to triumph.51

From a number of standpoints the drive for national Prohibition, which began in 1913, was an inexpedient movement. The Dry areas appeared to have been fairly successful in restricting liquor sales in the areas where Dry sentiment was strongest. In many urban areas, to be sure, the laws against sale were openly evaded. In the areas where sentiment was strongest against prohibitive legislation, urban parts of rural states and the urban states, laws had not been passed. By 1913 an equable arrangement appeared to have developed. Temperance sentiment was recognized where it was strong by both law and behavior. Where such sentiments were weak, the populace continued to act in accordance with their sense of what was culturally legitimate. Enforcement in urban areas where cultural support was small had been tried and had been shown to be at best a doubtful possibility. Contemplated in areas such as New York and Boston, it should have seemed an im-possible task to the reformer. Instead of deepening the enforcement of the law in areas already dry, the movement aimed at expanding its status as a recognized legal norm, as an ideal if not a behavioral reality.

It is in this characteristic of cultural conflict that the disinter-ested nature of coercive Temperance reform is manifest. Assimi-lative reform diminished as the Temperance advocates sought to coerce the nonbeliever to accept an institutional framework in which drinking was no longer socially dominant. VVhat we have shown in this chapter is that this facet, the coercive side of Tem-perance, emerged in a context in which the bearer of Temperance culture felt that he was threatened by the increasing strength of institutions and groups whose interests and ideals differed from his. He took a radical stand toward his society when he began to feel that he was no longer as dominant, as culturally prestigeful as he had been in an earlier period.

The development of Prohibition as a political measure focused these cultural conflicts in a form which maximized struggle. Elec-tions and legislative contests are fights; somebody opposes some-body else. One group tries to bring force to effectuate what an-other group detests, even though the force may be more potential than actual. The unwillingness of the potentially assimilable to follow the lead of the assimilative reformer is not a blow to the reformer's domination. The political victory of the norm-violator is, however, a blow to belief in one's domination, in his right to be followed in cultural and moral matters. It is the threat to dom-ination which the existence of drinking on a wide scale implied, both as a moral and legal norm and as a norm of recurrent be-havior. It became necessary to settle the issue by establishing social dominance through political measures, even if unenforceable.

Prohibition was an effort to establish the legal norm against drinking in the United States. It was an attempt to succeed in coercive reforrn. But in what sense can a legal norm, which is probably unenforceable, be the goal of a reform movement? If the drinlcing behavior which the movement sought to end occurred in communities in which the Temperance advocates were unlikely to live and the laws were not likely to be enforced, what was the rationale for the movement? We have shown that Prohibition had become a symbol of cultural domination or loss. If the Prohibition-ists won, it was also a victory of the rural, Protestant American over the secular, urban, and non-Protestant immigrant. It was the triumph of respectability over its opposite. It quieted the fear that the abstainer's culture was not really the criterion by which re-spectability was judged in the dominant areas of the total society.

1 Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucy Stone, the leaders of the Suffrage movement, were first active in Temperance organizations. We have already referred to Frances Willard's Suffragette commitment. Mary Livermore, one of the foremost feminists of the late nineteenth century, was President of the Massachusetts WCTU. The role of women in both the Feminist and the Temperance movements is treated in Arthur Schlesinger, "The Role of Women in American History," in his New Viewpoints in American History (New York: Macmillan, 1922), p. 136; Gilbert Seldes, The Stammering Century (New York: John Day, 1928), Ch. 17; Inez Haynes, Angels anti Amazons (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran and Co., 1933), pp. 80-90.

2 Accounts of the Temperance crusade by observers and participants can be found in Annie Wittenmyer, History of the Woman's Temperance Crusade (Philadelphia: Mrs. Armie Wittenmyer, 1878); Elizabeth Jane Thompson, Hils-boro Crusade Sketches (Cincinnati, Ohio: Jennings and Graham, 1906); Eliza Steward, Memories of the Crusades (Columbus, Ohio: William G. Hubbard Co., 1888); J. H. Beadle, Wosnen's War on Whiskey (Cincinnati, Ohio: Wilstach, Baldwin and Co., 1874). The crusaders spread across the country, similar ac8ons being reported for more than 300 communities. Most occurred in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and western New York.

3 For reports of the committee for work with fallen women see the Annual Report of the IVWCTU (1878), pp. 104-111; (1884), p. 40; (1894), p. 47.

4 This was a theme used by Veblen throughout Theory of the Leisure Class. Veblen's point was that female garments made labor impossible, hence dis-playing the ability of the husband or father to support such abstention from work.

5 In her presidential address of 1884, Willard said: "Niggardly waists and niggardly brains go together . . . the emancipation of one would always keep pace with the other. . . . Bonnetted [sic.] women are not in the normal condi-tion for thought; high-heeled women are not in the normal condition for motion; corseted women are not in the normal condition for motherhood." Annual Report of the NWCTU (1889), pp. 133-134.

6 Frances Willard, A Wheel Within a Wheel, or How to Ride a Bicycle (New York: F. H. Revell Co., 1895).

7 The Union Signal (October 11, 1894), p. 1.

8 Annual Report of the NWCTU (1877), p. 190; (1878), p. 183.

9 The Union Signal (May 16, 1889 ), p. 16.

10 In 1889 she joined the staff of The Dawn, the journal of the Nationalists, as the Society of Christian Socialists were also called. The motif of this group was that of the Socialist utopia inspired by Edward Bellamy's Looking Back-ward (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1889). A lengthy stay in England led to a close friendship with Lady Somerset, leader of the British Temperance movement and a member of the Fabian Society. Through her, Willard was influenced by Fabian Socialism.

11 See the Annual Repo-rts of the NWCTU for 1892-94.

12Ibid. (1889), p. 117.

13 Ibid. (1894), p. 334.

14 Thus Josephine Goldmark, looldng for some vehicle through which to press her concerns for social welfare work, turned to "Frances Willard's WCTU."

15 Again and again, one finds in accounts of reformers a display of a syndrome of movements including Temperance. People in Temperance were not likely to make it their sole outlet for reform. In Boston, for example, Vita Scudder and Mary Livennore were active in Feminism and Temperance. Often a special committee of the WCTU was headed by some women who had a prior and continued interest in another reform. In 1881, Wendell Phillips listed among the great social questions of the age feminism, temperance, and prison reform, a very common WCTU "package." Arthur Mann, Yankee Reformers in an Urban Age ( Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1954 ), p. 105.

16 Annual Report of the NWCTU ( 1884 ), pp. 65-69.

17 Paul Carter, Decline and Revival of the Social Gospel: Social and Political Liberalism in American Protestant Churches, 1920-1940 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Comell University Press, 1956), pp. 32-33.

18 D. L. Colvin, The Prohibition Party in the United States (New York: George H. Doran Co., 1926), Chs. 5-6.

19 Ibid., Chs. 7-9, 14.

20 For example, the 1884 platform of the Prohibition Party contained a plank addressed to Labor and Capital. It called attention to "the baneful effect upon labor and industry of the needless liquor business." No position was taken toward unions or strikes. It was claimed that Prohibition was the greatest thing that could be done to insure the welfare of laborers, mechanics, and capitalists. Ibid., p. 160.

21Fred Haynes, Third Party Movements (Iowa City: State Historical So-ciety of Iowa, 1918); Solon Buck, The Granger Movement (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1933), pp. 121-168.

22 Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1955), pp. 70-81.

23 For the speeches of St. John see Colvin, op. cit., Ch. 8.

24 The American Issue, 20 ( January, 1912), 4.

25/bid., 21 (June, 1913), 4.

26 Ibid., 20 (April, 1912), 1.

27 For a year-by-year chronology of the Prohibition movement see Ernest H. Cherrington, The Evolution of Prohibition in the United States (Westerville, Ohio: American Issue Publishing Co., 1920).

28 See the statistics on consumption of alcoholic beverages, corrected for age composition of population, collected by Mark Keller and Vera Efron and printed in Raymond McCarthy (ed.), Drinking and Into:cication (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, and New Haven, Conn.: Yale Center of Alcohol Studies, 1959), p. 180.

29 This interpretation is consistent with recent studies of the drinidng habits of ethnic and religious groups in the United States. Such studies show that a bimodal drinldng pattern is more typical of native American Protestants than of first- and second-generation Americans, both Catholics and Jews. The bi-modality implies that both abstainers and hard drinkers are more numerous among Protestants than among non-Protestants, where the moderate drinker is the more frequent case. In studies of college drinldng, for example, the Mormons had the highest percentage of abstainers of any religious group and Jews the lowest percentage. Mormons who did drink, however, showed patterns of excessive drinlcing more frequently than did Jews. Robert Straus and Selden Bacon, Drinking in College (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1953), p. 143. Other studies with supportive findings are Robert Bale, "Cultural Dif-ferences in Rates of Alcoholism," Quarterly Journal of Sttsdies on Alcohol, 6 (March, 1946), 480-498, and Charles Snyder, Alcohol and the Jews (Glencoe, M.: The Free Press, and New Haven, Conn.: Yale Center of Alcohol Studies, 1958).

30 Joseph Rovvntree and Arthur Sherwell, State Prohibition and Local Option (London: Hodden and Stoughton, 1900), using both systematic observations of small towns and cities and the payment of federal liquor sale licenses, con-cluded in 1899: "Local prohibition has succeeded [in the United States] pre-cisely where state prohibition has succeeded, in Rural and thinly peopled districts and in certain small towns . . . local veto in America has only been found operative outside the larger towns and cities" (p. 2,53).

31Norton Mezvinslcy, "Scientific Temperance Education in the Schools," History of Education Quarterly, 1 (March, 1961), 48-56.

32 Populist vote based on data reported in The World Almanac and &icy-clopedia--1894 (New York: The Press Publishing Co., 1894), pp. 377 ff.

33 Compiled from data in Anti-Saloon League Yearbook, 1913 (Westerville, Ohio: American Issue Publishing Co., 1913), p. 10.

34 Based on data in ibid., passim.

35 James Sellers, The Prohibition Movement in Alabama, 1702-1943, James Sprint Studies in History and Political Science, 26 (1943); Daniel Whitener, Prohibition in North Carolina, 1715-1945, ibid., 27 (1945). (Both published at Chapel Hill by the University of North Carolina Press.)

36 The World Aimanac and Encyclopedia—I894, loc. cit.

37 'This account is based on Gilman Ostrander, The Prohibition Movement in California, 1848-1933, University of California Publications in History, 57 (1957).

38 A statement by Willard Huntington Wright, quoted in ibid., p. 65.

39 In Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina, the counties most likely to have voted Dry in the post-Repeal period were those which were rural but where the percentage of Negroes was well below the state average. These were generally counties which had also been the basis of support for Populist candi-dates in the 1890's. This analysis is derived from county voting data in The World Almanac and Encyclopedia-1894, loc. cit., and Alexander Heard and Donald Strong, Southern Primaries and Elections (University: University of Alabama Press, 1950).

40 C. Vann Woodward, Origins of the New South, 1877-1913 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951), Ch. 9; V. O. Key and Alexander Heard, Southern Politics (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1949), Ch. 11.

41 Sellers, op. cit., pp. 46-48; Preston Slosson, The Great Crusade and After, 1914-1928, Vol. 12 in Arthur Schlesinger and Dixon Ryan Fox (eds.), A His-tory of American Life (New York: Macmillan, 1931), Ch. 4.

42 C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955), Chs. 1-2.

43 The American Issue, 21 (June, 1913), 4.

44 Ostrander, op. cit., p. 105.

45 Virginius Dabney, Dry Messiah (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1949), p. 128.

46 Anti-Saloon League Yearbook, 1911, p. 4.

47Henry May, Protestant Churches and Industrial America (New York: Harper and Bros., 1949).

48 Peter Odegard, Pressure Politics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1928), esp. Chs. 3-5.

49 While some of the Dry leaders, such as Bishop Cannon, had been sym-pathetic to other reform movements, they can hardly be said to have played an important role in them at any point in their lives.

50 The organized Temperance movement among Catholics was greatly weak-ened by the tum of the Temperance movement toward Prohibition. The Catho-lic Temperance Union did not support Prohibition at any time. See Sister Joan Bland, Hibernian Crusade (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University Press, 1951).

51 Ostrander, op. cit., p. 104.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|