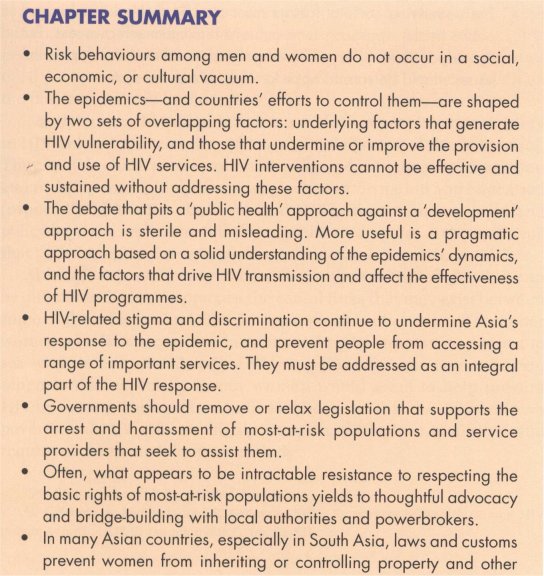

4 Towards a More Effective HIV Response

| Reports - Redefining AIDS in Asia |

Drug Abuse

THE COMPLEXITY OF THE UNDERLYING LINKS BETWEEN SOCIETAL FACTORS, ENVIRONMENT, AND HIV

Focused interventions that have proved successful in preventing the spread of HIV among most-at-risk populations are well-documented, and should form the core of HIV prevention programmes.1

Free provision of treatment can help sustain the livelihoods of affected families. Impact mitigation, by way of social protection packages, will also reduce the adverse consequences of AIDS deaths at household, community, and national levels. Such interventions should be part of the core business of the HIV response.

But the challenge should not be oversimplified. Neither the behaviours that entail high risks of HIV infection, nor the interventions aimed at reducing them, occur in a social, economic, or cultural vacuum. These behaviours are shaped by underlying social dynamics, which render some people more vulnerable to HIV and its effects. Moreover, the outcomes of HIV interventions are shaped by factors that may hinder or facilitate the delivery and use of those services.

The dynamics that shape behaviour and affect people's vulnerability to HIV are sometimes referred to as 'social drivers' of the epidemics. They may include socio-economic and gender inequality, migration and mobility, trafficking of women, lack of information and education (especially ignorance about sex and HIV), discriminatory legal and policy barriers, and more. It is this multifaceted nature of the epidemic that calls into play the need for a multisectoral response to HIV.

Although relatively easy to describe at the conceptual level, it can be difficult to discern in practice the causal links that may exist between some of these factors and HIV. For example, it is often argued that poor women who lack access to education and social support may resort to sex work to earn livelihoods. Following this logic, poverty-reduction schemes that especially favour women would seem to help prevent HIV infections. The evidence indicates, however, that the links between poverty and HIV risk are highly complex, difficult to quantify,2 and require sophisticated, long-term study.

'AN ENABLING ENVIRONMENT' CAN QUICKLY REDUCE MANY BARRIERS TO PREVENTION AND CARE

Many of the factors that deepen susceptibility to HIV infection also affect the extent to which people obtain access to HIV-related services. This aspect of risk reduction is often neglected both in the HIV literature and programme design, although it is occasionally captured in the concept of 'enabling environments'. At the programmatic level, it is vital to identify and address factors that impede the scope, reach, operation, and use of HIV services.

For example, since large-scale poverty reduction schemes can require 20 years or more to yield tangible results, their impact on HIV transmission is even more difficult to quantify. Yet it is clear that people living in poverty are considerably less likely to gain access to healthcare services (even when provided free of charge), often because of the additional costs they entail (including transport expenses, opportunity costs such as loss of income, and more). Those barriers can be removed—for example, by providing subsidized transportation to clinics or by ensuring that clinics operate after-hours on some days of the week.

Such interventions will not eradicate poverty, but they can, in a short space of time, render important healthcare services more accessible to poor people. These kinds of initiatives are especially important when it comes to providing services to most-at-risk populations.

The successful implementation of HIV interventions therefore demands, first of all, that local-level barriers be addressed and that an 'enabling environment' must be created. This is not difficult to achieve. Often, what appears to be intractable resistance to respecting the basic rights of most-at-risk groups yields to thoughtful advocacy and bridge-building with local authorities and powerbrokers.

The epidemics and the efforts to control them are shaped by two sets of overlapping factors: the underlying dynamics that generate HIV vulnerability (or 'social drivers'), and the factors that undermine or boost the provision and use of HIV services (the 'enabling environment'). Progress is required on both fronts if an HIV response is to have a realistic chance of achieving lasting success. The question is how to achieve this, the subject to which we now turn.

INFORMATION AND KNOVVLEDGE ENABLES PEOPLE TO MAKE BETTER INFORMED CHOICES ABOUT THEIR SEXTJAL BEHAVIOUR

It is commonly believed that better knowledge about sexual and reproductive health can enable people to make better-informed choices about their sexual behaviour, and to guard their health with greater success. High levels of ignorance about HIV (and about sex in general) persist in much of Asia, largely because sex education is either poor or non-existent. Such ignorance is linked to societal norms and mores that associate sexual ignorance and inexperience in women with virtue.

Studies carried out in India and Viet Nam, for example, have shown that young women often know little about their bodies, pregnancy, contraception, or sexually transmitted infections, and that many avoid seeking information about sex for fear of being labeled promiscuous. A study among young brides in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh foun.d that 71 per cent of the women (some of whom had been in their early teens when_ jhey married) knew nothing about how sex occurs, and 83 per cent did not know how women become pregnant.3 In Viet Nam, more than two-thirds of young women (aged 15-24 years) did not know the three main methods for preventing HIV transmission.4,6

Ironically, although notions of innocence, purity, and virginity are not imposed on men, many of them are also unschooled about sexual matters largely because they too have received little or no sex education. In a recent review of the Millennium Development Goal indicators for young people from nine countries in Asia, no country reported more than a 50 per cent level of sexual knowledge among boys, with some countries reporting as low as 3 per cent.6 In several Asian societies, this aversion to sex education is rooted in taboos about the public discussion of sex.

Such ignorance includes even those people most at risk of HIV More than half of the sex workers surveyed in the Indian state of Haryana did not know that condoms can prevent HIV transmission,7 while in Karachi (Pakistan) one in five female sex workers surveyed could not recognize a condom, and three-quarters did not know that condoms prevent HIV (indeed, one-third had never heard of AIDS). Not surprisingly, only 2 per cent of the women said they had used condoms with all their clients in the previous week.8

It is possible to overcome such ignorance among most-at-risk populations in ways that are non-judgemental and that do not fuel wider social prejudice and taboos. Thailand achieved this goal in the early 1990s. A recent study has confirmed the impact of the mass media campaign that was a central part of its HIV prevention programme. In the case of male clients of sex workers, the Thai experience also shows that HIV publicity aimed at most-at-risk groups works best when it is frank and avoids moral judgement. The study concluded that a well-designed mass media campaign is a prerequisite for a potentially successful HIV response.8

Knowledge of HIV was shown to be poor among surveyed groups of men who have sex with men. For example, in Bangalore (India) three in four men who have sex with men did not know how the virus is transmitted, and a large proportion of them reported not using condoms during sex.1° Basic HIV knowledge is also lacking among injecting drug users. A study among injectors in China's Yunnan province, for example, found that one in five did not know that needle-sharing carries a high risk of HIV transmission.11

POVERTY AND INEQUALITY LIMIT ACCESS TO ESSENTIAL HIV SERVICES

Poverty greatly affects the risks people take. When basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter are not met, individuals, particularly women, may find themselves drawn into sex work, for example. Poverty also diminishes the abilities of individuals, households, and families to deal with the effects of HIV infection. Often, the failure to manage an infection will lead to further impoverishment.

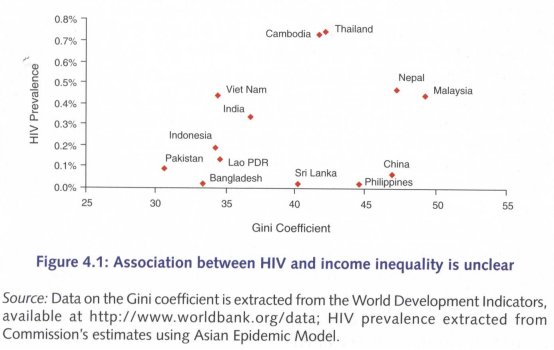

Nevertheless, income poverty appears not to be a significant risk factor driving Asia's HIV epidemics. Many (but by no means all)12 drug injectors are poor, although often as a consequence of their addictions. While some clients of sex workers might be classified as poor, it is not their poverty that impels them to buy sex or not to use condoms. By definition, clients need disposable income in order to buy sex, and some are even willing to pay extra in order to have unprotected sex. At the macro level too, no clear relationship exists between income inequality (as measured by Gini coefficient)13 and HIV prevalence, as shown in Figure 4.1.

Poverty in the context of HIV seems best addressed by removing factors that block access to prevention services and antiretroviral treatment. With respect to treatment, this goal can be achieved by the use of subsidies (including subsidies for transport and laboratory expenses) as well as by involving community groups and non-governmental organizations in the early recruitment of poor households into treatment networks and by ensuring that impact mitigation programmes reach them.14

GENDER INEQUALITY ENHANCES THE RISK OF HIV FOR WOMEN

Women and girls face a range of HIV-related risk factors and vulnerabilities that men and boys do not—many of which are embedded in the social relations and economic realities of Asian societies.

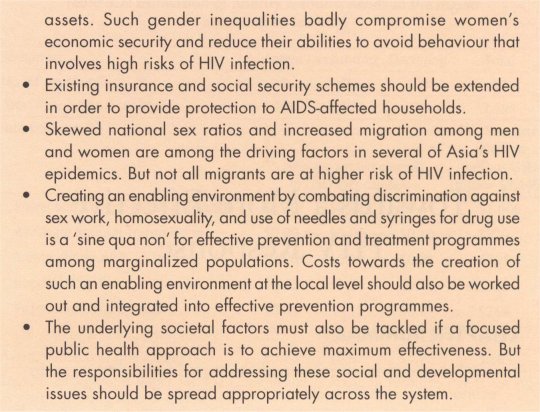

Women generally have more difficulty than men in gaining access to education, accessing credit and support services, and finding formal employment that matches their skills. In many countries, laws and customs prevent them from controlling property and other assets (especially in South Asia). These gender inequalities compromise women's economic security and reduce their ability to avoid behaviour that involve high risks of HIV infection.15 For that reason (and many others), such material inequalities must be addressed. However, removing or even significantly reducing them can take decades, even generations.

Women's unequal social status is also reflected in sexual relationships, where men are more likely than women to initiate, dominate and control sexual and reproductive decisions. In a society dominated by patriarchal values, where men dominate decision-making in the household and society, women are not usually free to decide when and with whom to have sex, and whether or not to use a condom when doing so. As a result, many women are unlikely to negotiate condom use even when they are aware of the risk involved or suspect the HIV status of their husband. It is estimated that for 90 per cent of HIV-infected women in India, and 75 per cent of HIV-infected women in Thailand, marriage was the only factor that put them at risk of HIV infection.

Generally, women and girls provide the bulk of home-based care (in Viet Nam, for example, women make up 75 per cent of all caregivers for persons living with HIV) and are more likely to take in orphans, cultivate crops, and seek other forms of income to sustain households.16 Gender inequalities tend to aggravate the vulnerability of such households, especially where women are denied equitable access to livelihood opportunities. Indeed, improved social protection policies for women are feasible in the area of impact mitigation, and some of these measures also offer opportunities for HIV prevention for women.

Economic assets, such as land and housing, provide women with a source of livelihood and shelter, thereby protecting them when a husband or father's disability or death places the family at risk of poverty. Control over such assets can give women greater bargaining power within households and can act as a protective factor in domestic violence. Research in the Indian state of Kerala found that 49 per cent of women with no property reported physical violence compared to only 7 per cent of women who owned property.17 Moreover, land and housing provide a secure place to live, serve as collateral for loans during financial crisis, and are symbols of status in most societies—all of which can benefit women who are contending with a health crisis in the household.

In many countries, laws and customs prevent women from owning or inheriting property and other assets. This is particularly true of South Asia where gender inequalities in women's rights to property significantly compromise women's economic security and reduce their ability to avdid situations that involve a high risk of HIV infection.18 Even where the law is not gender biased, women whose husbands or fathers fall sick and die of AIDS, or women who are sick themselves, often lose their homes, inheritance, possessions, and livelihoods either because of 'property grabbing' by relatives and community members or because they have no access to legal redress to regain ownership of property.

Legal and other obstacles that prevent women (including those widowed by AIDS) from inheriting assets must be removed. Special support (including cash transfers or subsidies for education, transport, and food expenses) should be available to families fostering children orphaned by AIDS. More generally, income support should be available to women in AIDS-affected households, irrespective of whether the women are infected with HIV. Also valuable would be the extension of existing insurance and social security schemes to ensure they provide protection to AIDS-affected households.

The potential benefits of such interventions extend far beyond AIDS-affected individuals and households. The HIV epidemic, in other words, provides countries with a valuable opportunity to strengthen social protection programmes for meeting catastrophic health expenditures. Such impact mitigation efforts fit best within existing or nascent social development programmes; they should not be set up as stand-alone programmes. The best approach is to integrate them into existing or future national social security programmes.

Where such programmes do not exist, AIDS budgets could be used to catalyse social protection schemes to be undertaken by social welfare ministries. Seed money from AIDS budgets could be used to leverage additional resources for social security programmes, as well as catalyse legal changes and affirmative actions for women.

IN SOME PLACES, MIGRATION CONTRIBUTES TO THE DEMAND FOR SEX WORK

Economic inequality in the midst of rapid development also tends to lead to large-scale migration, which maybe associated with sexual risk-taking (mainly the buying or selling of sex).

In China, for example, the skewed national sex ratio and increased migration (mainly from rural to urban areas) are believed to be contributing to the demand for sex work,19 and several studies have highlighted sexual risk-taking behaviour among some groups of migrants.20,21 A 2003 survey in the southwest of China found that temporary female migrants were 80 times more likely than non-migrants to sell sex.22 In Viet Nam, high levels of injecting drug use and sex work among young male migrant workers (1 6-26 years of age) underline the need for prevention programmes that reach migrants.23

In Nepal, it is estimated that almost half of all people living with HIV have worked as migrant labourers.24 Nepalese girls and women who have been sex-trafficked are at especially high risk of HIV infection: an HIV prevalence of 38 per cent has been found among repatriated sex-trafficked females.25 There are also concerns about the potential role of migrant labour in Pakistan's epidemic. In Lahore, for example, one in ten (11 per cent) unmarried male migrant workers reported having had unprotected paid sex in the previous year.26

Generalizations, however, can mislead. Significant numbers of migrants move with their partners, and HIV-related risk-taking tends to be lower among this group. Equally, there is research evidence that conservative social norms survive longer among migrants than is commonly thought; for example, where paying for sex is seen as unacceptable.27 It is therefore not the case that all migrants are necessarily at higher risk of HIV infection.

STIGMA AND DISCRIMINATION FUELS HIV EPIDEMICS

HIV-related stigma and discrimination continue to undermine Asia's response to the epidemic, and prevent people from accessing a range of important services. The take-up of HIV testing and counselling services is low and probably will remain so unless stigma and discrimination are redp.ced, and integrated prevention, treatment, and care programmes are more widely available. Equally, discrimination against people infected with or affected by HIV continues to affect their access to employment, housing, insurance, social services, education, and health care.

In several countries, studies in healthcare settings, for example, have documented disturbing levels of igmorance about HIV and strong prejudice against people living with HIV.28 Stigma is a problem in the healthcare systems of both India29 and China, among others. In a 2005 survey of almost 4,000 nurses in China's Guangxi, Sichuan and Yunnan provinces, for example, almost one in five (18 per cent) said patients with HIV should be isolated,3° while in another study in Yunnan Province almost one in three (30 per cent) health professionals participating said they would not treat an HIV-positive person.31

Stigma and discrimination persist not only with respect to people living with HIV, but also with respect to those most-at-risk of becoming infected. In many ways, these groups are already marginalized and/or criminalized by the penal code, which makes it all the more important that their rights be protected. Sex work, drug injecting and sex between men is illegal throughout much of Asia. Licensed sex work is allowed only in the Philippines and Singapore. The possession of certain narcotics, meanwhile, can carry the death sentence in four Asian countries (China, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand). Sex between men is not illegal in only five Asian countries.

Irrespective of the legal status of such behaviours and the nominal rights of people engaging in them, the typical experiences of those people most-at-risk include harassment, and the (sometimes violent) violation of their basic human rights. Indeed, the experience of men who have sex with men in Cambodia (where it is legal) underscores the fact that the legal status of same-sex relations does not necessarily determine the conduct of law enforcement authorities.32

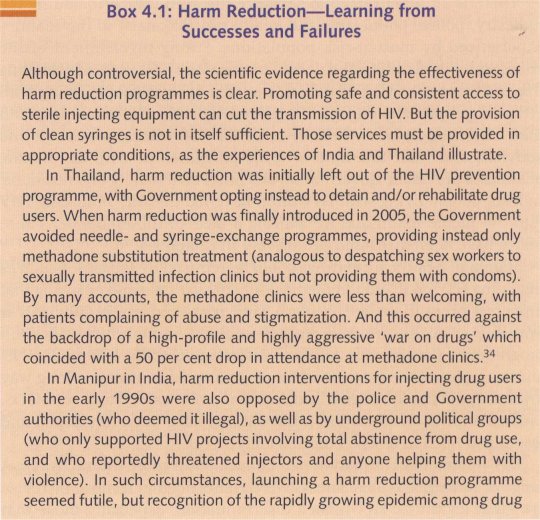

The criminalization of those groups which are most-at-risk tends to drive them underground and fosters distrust of state officials and projects. Harassment not only makes it difficult to supply these groups with HIV services, as documented in Thailand (see Box 4.1), it often precipitates the risk behaviour itself. For example, in Kolkotta, India, intensified police activity was recorded as the main reason for switching from smoking to injecting drugs, facilitating risk for HIV infection.

Partly as a result of such heavy-handedness, ignorance about HIV and other health risks can be surprisingly widespread among the groups that are most-at-risk. Harassment discourages people from carrying condoms or clean syringes (to avoid giving the police a pretext for arresting them). The fact that injectors can buy needles in pharmacies is of little consequence if they risk arrest for being in possession of the needles; this is the reason most commonly cited by injectors in Indonesia and Nepal for not using clean equipment.33

In addressing stigma and discrimination, it is useful to bear in mind that the two concepts are quite distinct. Stigma involves an attitude, and often provides the underlying basis for discrimination, which entails an act. Each, in other words, fuels the other. Yet, they are best tackled in ways that reflect those differences.

There is an urgent need to sensitize the authorities (including the judiciary, police, politicians, and health professionals) to the realities experienced by most-at-risk populations. Strong involvement of the community in planning and desig-n is one of the best ways of achieving this. An important way of reducing stigma against people living with HIV and people who engage in high-risk behaviour is to support both their efforts to organize themselves as HIV advocates, educators, and activists, and their attempts to forge partnerships with the media, healthcare providers, Government, and other civil society organizations. Indeed, people living with HIV often have led the way in forcing HIV into the public realm and by 'putting a face' to the epidemic. These issues have been discussed extensively in Chapter 6.

Stigma in healthcare settings could be reduced by measures such as including HIV education in medical school curricula and ensuring that universal precautions are in place (and post-exposure prophylaxis is available to healthcare workers). In addition, community education programmes that provide accurate information about HIV and AIDS, and examples of the ways in which stigma spreads, can go a long way towards reducing the stigma and discrimination associated with AIDS. Curricula for such education interventions have been developed and tested and need to be used more widely.

HIV-related discrimination can be tackled in more 'literal' ways. A range of remedies is available. Governments need to remove or revise laws that legitimize HIV-related discrimination, especially those that regulate the labour market, the workplace, access to medical and other forms of insurance, healthcare and social services and inheritance rights (particularly of women). More generally, HIV-related discrimination needs to be systematically monitored and publicized by 'AIDS Watch' bodies.

A few countries (notably China and Viet Nam) have altered their laws to grant drug users a legal right to needle and syringe exchange and drug substitution programmes. But changing the law can be time-consuming and does not guarantee a change in conduct at the local level. One practical solution would be to introduce legal provisions that provide legal immunity to both beneficiaries and service providers of HIV interventions (an example of such a proposed legislation found in the technical Annex).

CREATE AN ENVIRONMENT TO FACILITATE SERVICES FOR MOST-AT-RISK GROUPS

Efforts to provide or use HIV services aimed at most-at-risk groups can encounter serious obstacles; but most of those obstacles can be removed by creating appropriate 'enabling environments'. Below is a checklist of relevant measures:

• the affected community must be involved in designing, implementing, and assessing delivery of the services;

• local power relations (involving the police, religious, and other social leaders, politicians, and local goons) and other factors that could affect the project need to be understood;

• interventions should incorporate elements that also address some of the other pressing, subjective needs of beneficiaries (such as child care for sex workers, legal support for dealing with police harassment, safe spaces that offer shelter against violence, or toilet and resting facilities for street-based sex workers);

• negotiations should be held with local power brokers and service providers;

• support is necessary for setting up and running local community organizations; and,

• budgets must include funding for these activities.

Avoiding HIV infection is seldom the main concern of sex workers or drug injectors, mainly because of the need to deal with daily hardships like police harassment, the threat of violence, and the need for safe shelter and income. Exhortations to practise safe sex or only to use clean needles ring hollow. This is why it is so important that HIV interventions occur in ways that also address other, subjective priorities of those groups most at risk.

Fostering a sense of respect and trust, or providing safe spaces in otherwise unsafe settings, can make a difference. Drop-in centres, for example, provide temporary havens where people can gather, share their experiences and ideas, gain information and link up to relevant services (whether HIV testing and counselling, treatment for sexually transmitted infections or finding a room to rent).

Similarly, liaison efforts that aim to reduce the harassment and violence that sex workers and other most-at-risk populations experience at the hands of the police or thugs are valuable elements of an HIV intervention. Providing a crèche for sex workers' children, facilitating the creation of retirement plans with bank-based savings, or offering a voluntary detoxification service for injecting drug users not only build trust but permit people to think beyond their immediate survival needs.

It is important that HIV budgets make provisions for creating such 'enabling environments'. Substantial funds are earmarked for creating such environments in some interventions in South Asia, including in Nepal and India.35 Standard guidelines for costing such programmes hdve also been published.36

In addition to addressing the stigma and discrimination experienced by people living with HIV and their relatives, special attention needs to be paid to disempowered groups of people living with HIV, such as women, poor people, and migrants. Underlying factors that lead to discrimination against these groups may require long-term approaches, but in the short term, enabling interventions should be in place to reach, recruit, offer treatment and testing, and provide them with livelihood security.

STRIKING THE RIGHT BALANCE--ADDRESS IMMEDIATE PRIORITIES AND CATALYSE LONG-TERM ACTIONS

Factors that hinder access to, as well as delivery and utilization of, HIV services have a direct bearing on the outcomes of HIV programmes.

Similarly, certain factors render some people particularly vulnerable to the impact of the epidemic. Although all such factors must be addressed as part of a comprehensive multisectoral response, they cannot be tackled in the same timeframe, or by the same institutions and with the same strategies. Some yield to short-term interventions, others require pervasive social changes that can take decades to achieve.

Balancing the short- and long-term approaches within AIDS programmes often poses a dilemma; finding the right balance is not always easy. As early as 1997, UNAIDS raised the concern that a focus on underlying factors that seemed to drive HIV epidemics might lead to the neglect of other urgent interventions that were more likely to bring short-term results. It also raised the important question of whether such manifold activities might compromise the focus, and drain the resources, of HIV programmes.37

To varying degrees, these questions have been reflected in the planning and resource allocation decisions of countries over the past decade. Recognizing this, the Commission reviewed countries' practical experiences in dealing with these issues.

It is now recognized that there has been a relative failure to protect those people who are at immediate and high risk of HIV infection, and those who are especially vulnerable to the effects of AIDS illness and death. This is true despite the fact that the positive impact of practical, short-term interventions—of the kinds outlined above—is well-documented. In a similar vein, remedial measures are available for increasing access to and use of services that have been shown to reduce the risk of HIV infection. These more immediate actions are generally recognized, but they are seldom costed and integrated into countries' HIV strategies.

Take, for example, the relationship between sex work and HIV. The evidence shows clearly that reducing the number of men who buy sex and increasing condom use during paid sex are the two most important steps needed to stop the spread of HIV in Asia. But there is also a view that programmes that might help women avoid becoming sex workers should be given priority even when such programmes are unlikely to have a short-term impact on the HIV epidemic.

Similarly, many Governments seem to shun harm reduction programmes in favour of efforts to prevent young people from using drugs. While both those interventions are important, harm reduction should be given priority in designing the HIV response; the evidence shows that it leads to an immediate reduction in new HIV infections. In light of this, the Commission recommends that:

1. Programmes that prevent new infections and that reduce the epidemic's impact by providing treatment, care and support services must remain at the top of the agenda in Asia, and countries should ensure that sufficient resources are made available to achieve this. The core business of HIV programmes should be dearly delineated and should focus on interventions that promise maximum effectiveness. At the same time, for an HIV response to achieve widespread and lasting success, the contextual factors that affect HIV interventions must be addressed—without sacrificing the focused approach advocated in this Report. The creation of an 'enabling environment', especially at the local level, is an essential contextual factor, which needs to be integrated into all components of HIV programmes.

2. The underlying dynamics that shape behaviours and affect people's vulnerability to HIV need to be properly understood and addressed to achieve maximum and long-term effectiveness of programmes. The responsibilities for addressing the long-term developmental goals need to be spread appropriately across the system, including civil society. In so far as they potentially relate to the HIV response, they can be supported from within the national HIV program/ne. HIV programmes can catalyse or provide seed funding for some initiatives, provide technical and other guidance for the design, implementation and monitoring of programmes that are vested with various sectors of social and economic development. National AIDS Commissions (rather than the national HIV programmes) should be responsible for advocacy and mobilizing resources from these sectors in order to mount a more comprehensive and multisectoral response to HIV in Asia.

These two items appear in Chapter 7 as Prevention Recommendation 1.3 and Policy Recommendation 7.3, respectively.

1 See Chapters 2 and 3 for detailed discussion.

2 S. Gillespie, S. Kadilyala and R. Greener (200'7), 'Is poverty or wealth driving HIV transmission?', AIDS, 21 (supplement 7), pp. S5-S16.

3 M.E. Khan, et al. (2004), Sexual violence within marriage, Vadodara: Centre for Operations Research and Training.

4 The three main methods for preventing the sexual transmission of HIV are: avoid penetrative sex, use condoms when having sex, or have sex only with one, uninfected partner.

5 Committee for Population, Family and Children and ORC Macro (2003), Vietnam Demographic and Health Survey 2002, Calverton: Committee for Population, Family and Children and ORC Macro.

6 Bergenstrom, A. and P. Isarabhakdi (forthcoming), 'Comparative analysis of sexual and drug use behaviour and HIV knowledge of young people in Asia and the Pacific', in A. Chamratrithirong and S. Kittisuksathit (eds), HIV Epidemic among the General Population of Thailand: National Se,xual Behavior Survey of Thailand, volume 2, 2008, 2nd Report.

7 MAP (2004), AIDS in Asia: Face the facts, Bangkok: Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic Network, available at

8 MAP (2005), Sex work and HIV/AIDS in Asia—MAP Repor t, July, Geneva: Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic Network.

9 M. Sarkar (2007), 'HIV prevention mass media advertisements and impact on sexual behavior—A study of the 1990's mass media campaign in Thailand', Background paper for the Commission on AIDS in Asia; Full paper is available in the Technical Annex.

10 Anthony et al. (2006), 'Men who have sex with men in southern India: Typologies, behaviour and implications for preventive interventions', Abstract CDD0331, XVI International AIDS Conference, 13-18 August, Tbronto.

11 J. Christian, et al. (2006), 'Risk behaviour among intravenous drug users and improved programming in Yunnan province, China', Abstract MOPE0479, XVI International AIDS Conference, 13-18 August, Tbronto.

'12 Research in Indonesia, for example, found that a significant proportion of drug injectors were from middle-class backgrounds, and a large proportion of them were (at least initially) not socially marginalized: more than 4 out of 5 injecting drug users in three cities lived with their parents or family members, and had at least a high-school education (MAP 2004).

13 Gini coefficient is a measure of inequality of income distribution, ranging from 0 (perfect equality, where everyone has equal income) to 100 (perfect inequality, where one person has all the income).

14 Further details of components of impact mitigation programme, provided in the lbchnical Annex.

15 UNAIDS/WHO (2004), AIDS Epidemic Update—December 2004, Geneva: UNAIDS.

16 1 Ogden and S. Esim (2003), Reconceptualizing the care continuum for HIV/AIDS: Bringing carers into focus, Desk review draft, Washington DC: International Center for Research on Women.

17 S. Panda, et al. (2002), 'Drug use among the urban poor in Kolkata: Behaviour and environment correlates of low HIV infection', The National Medical Journal of India, 15 (3), pp. 128-34.

18 UNAIDS/WHO (2004), AIDS Epidemic Update—December 2004, Geneva: UNAIDS.

19 J.D. Bucker, et al. (2005), 'Surplus men, sex work and the spread of HIV in China', AIDS, 19, pp. 539-47.

20 B. Wang, et al. (2006), 'HIV-related risk behaviors and history of sexually transmitted diseases among male migrants who patronise commercial sex in China', Abstract MOACO305, XVI International AIDS Conference, 13-18 August, Tbronto.

21 C.J. Smith and X. Yang (2005), 'Examining the connection between temporary migration and the spread of STDs and HIV/AIDS in China', The China Review, 5 (1), pp. 109-37.

22 X. Yang and G. Xia (2006), 'Gender, migration, risky sex and HIV infection in China', Studies in Family Planning, 37 (4), pp. 241-50.

23 L.M. Giang, et al. (2006), 'HIV risks among young male migrants using heroin in Hanoi, Viet Nam', Abstract WEAD0204, XVI International AIDS Conference, 13-18 August, Toronto.

24 WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS (2006), 'Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections: Nepal', December, Geneva: World Health Organization, available at EFS2006_NP.pdf.

25 J.G. Silverman, et al. (2007), 'HIV prevalence and predictors of infection in sex-trafficked Nepalese girls and women', Journal of the American Medical Association, 298 (5), pp. 536-42.

26 A. Faisel and J. Cleland (2006), 'Migrant men: A priority for HIV control in Pakistan?', Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82 (4), pp. 307-10.

27 T. Hesketh, et al. (2006), 'HIV and syphilis in migrant workers in eastern China', Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82 (1), pp. 11-4.

28 Asia Pacific Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS (2004), 'AIDS Discrimination in Asia, Bangkok', available at

29V.S. Mahendra, et al. (2006), 'How prevalent is AIDS-related stigma among health care workers? Developing and testing a stigma index in Indian hospitals', Abstract TIJPE0729, XVI International AIDS Conference, 1 3-1 8 August, lbronto.

30 S. Sun, et al. (2006), 'Health providers' attitudes towards mandatory HIV testing in China', Abstract TUPE0782, XVI International AIDS Conference, 13-18 August, Tbronto.

3I T. Hesketh, et al. (2005), 'Attitudes to HIV and HIV testing in high prevalence areas of China: Informing the introduction of voluntary counselling and testing programmes', Sexually Ransmitted Infections, 81, pp. 108-1 2.

32 K. Sovannara and C. Ward (2004), 'Men who have sex with men in Cambodia: HIV/AIDS Vulnerability, Stigma and Discrimination', Policy Project, available at http:// www.policyproject.com/pubs.cfm.

33 MAP (2004), AIDS in Asia: Face the facts, Bangkok: Monitoring the AIDS Pandemic Network, available at

34 UNAIDS (2006), 'From advocacy to implementation: Challenges and Responses to Injecting Drug Use and HIV', Speech delivered at XVII International Harm Reduction Conference, Vancouver, Canada.

35 NACO and UNAIDS (2002), Costing of focused interventions among different sub-populations in India: A case study in South Asia, Delhi, available at http:// www.nacoonline.org; NACO (2004), Costing guidelines for targeted interventions, Delhi, available at

36 Costing Guidelines for HIV/AIDS Intervention Strategies (2004), Bangkok-Manila, UNAIDS-ADB.

37UNAIDS (1998), 'Expanding the global response to HIV/AIDS through focused action: Reducing risk and vulnerability: definitions, rationale and pathways', Geneva: UNAIDS.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|