5 National HIV Responses in Asia

| Reports - Redefining AIDS in Asia |

Drug Abuse

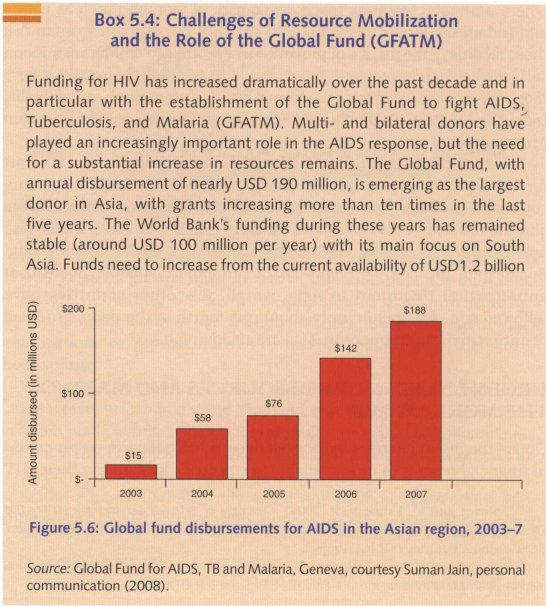

CURRENT RESPONSES FALL SHORT IN MAKING A MAJOR IMPACT

The Asian experience has much to tell us—both good and not so good—about national HIV responses.

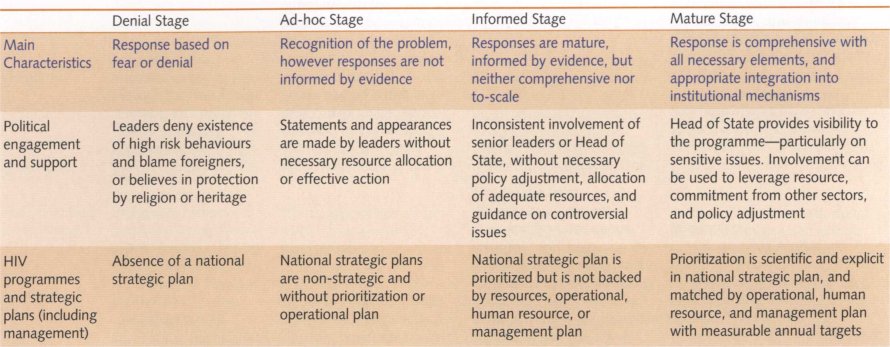

In a few instances, strong and focused efforts have brought striking results on a large scale, as the examples of Cambodia, Thailand, and the Indian state of Tamil Nadu reveal. Elsewhere, efforts are improving even if the benefits are less apparent. In many cases, the response to HIV has either lagged behind or faltered for long periods. Increasingly, elements of a potentially effective response are being introduced (see Box 5.1), but the degree of urgency, coherence, and scale needed to curb the epidemics is not yet evident.

All these experiences offer lessons for improving HIV responses in Asia to the point where the epidemics can be subdued and eventually halted. While there is no blueprint for the 'ideal' HIV response, Asia's experiences to date reveal a series of prerequisites and pitfalls that can guide countries in their bid to strengthen the response to HIV.

It can take several years before the effects of a 'successful' national response become evident in the form of a decline in the national level of HIV prevalence. A drop in prevalence, therefore, is an imperfect indicator of the impact of an intervention. More useful indicators are the ones that allow for the assessment of the following aspects of HIV responses:

• political engagement and support;

• HIV programmes and strategic plans;

• resource mobilization and making the money work;

• civil society and community participation;

• the creation of a better policy and legal environment (especially in relation to HIV-positive persons and most-at-risk populations);

• institutional structures and governance;

• the external response and the role of international partners.

POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT NEEDS TO BE STRONG

Strong political commitment and leadership have proved to be prerequisites for setting the agenda and driving a potentially effective response. It was decisive in Thailand's response in the early-to-mid 1990s, and it provided vital impetus to the HIV programmes that have unfolded subsequently in countries like Cambodia, China, India, and Indonesia.

In those and other countries, far-sighted politicians have built awareness among their constituencies, lobbied for HIV-related legislation, pushed for more HIV resources, or tried to hold their Governments accountable for their countries' HIV responses. Parliamentary committees on HIV have been set up in a few countries, and they have also given rise to regional networks that focus on HIV and sexual and reproductive health.

When it comes to dealing with issues of stigma and discrimination, and overcoming taboos on the public discussion of sex and sexuality, the role of leadership cannot be underestimated. This is particularly true in Asia, because the epidemic is driven by stigmatized behaviours such as drug use, sex work, and sex between men. Leaders can create an enabling environment for addressing these issues by facilitating the involvement of civil society and community groups, mobilizing public opinion or earmarking resources for such activities. Political commitment is also important for instilling a sense of urgency.

Much has been made of the need for explicit support from political leaders. Indeed, leaders of all the countries in the region signed the UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) Declaration,5 and later committed their countries to the Universal Access initiative.6 Unfortunately, in many cases those official commitments have not yet translated into sufficient and tangible actions at national level.

In only two countries in Asia has a Head of State, for example, provided leadership to the national AIDS programme as its chair. Other elements of demonstrable leadership would include championing practical policies, ensuring adequate resources, and establishing a strong management structure (such as a National AIDS Commission), and involving civil society in the response.

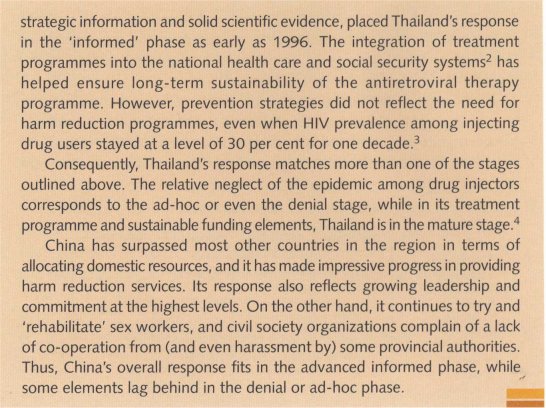

As Figure 5.2 shows, political commitment changes over time. The information used to compile this graph was drawn from a leadership mapping study conducted by the Asia Pacific Leadership Forum (APLF). It found that most countries in the region strengthened their political commitment to the HIV response, although some lost ground after having achieved initial success in controlling their epidemics.

In the Philippines and Thailand, political leadership appears to have lost momentum over the period surveyed, while in Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, and Malaysia, it has increased considerably. It is important to understand what prompts political leaders to embrace and then remain committed to HIV advocacy and action. In some cases, strong advocacy and activism have spurred leaders into action, but generally, political leadership and engagement appear to have emerged from three factors: a mature and pragmatic sensibility among leaders (such as seen in Thailand in the early 1990s), recognition of the urgency of the situation (for example, China and India) and pressure from civil society (for example, the Philippines).

What is clear currently is that political leadership on HIV needs to be strengthened in Asia as well as sustained. The process of building impetus tends to originate within the community of AIDS activists—as has been evident in countries as diverse as Brazil, South Africa, and the United States of America.

HIV PROGRAMMES AND STRATEGIC PLANS STILL LACK KEY PLANNING COMPONENTS

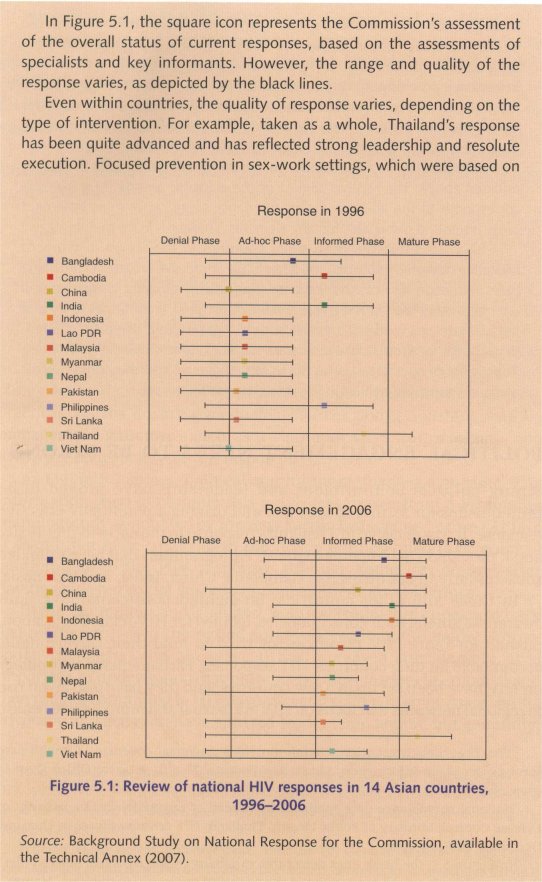

The Commission's review of HIV responses in 14 Asian countries revealed that all of them have national strategic plans, but the quality of those plans varies significantly. Some countries lack the necessary strategic information to create an informed response, while others are premised on incomplete interpretations of the data. In some national plans, resource allocation does not match the priorities highlighted. A few plans seem to be based on misinterpretations of international best practices. Overall, most of the plans still lack key planning components for the operation, management, and financing of the response.

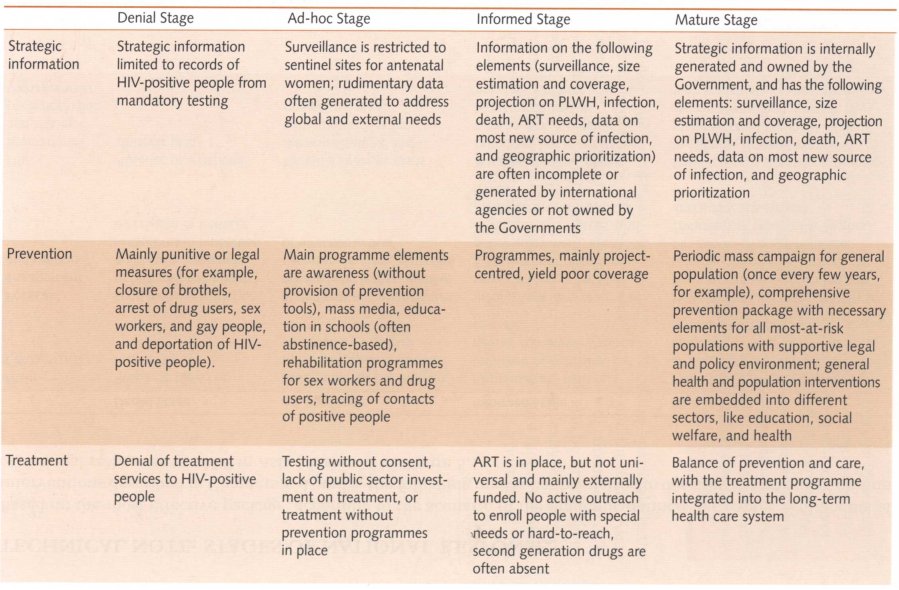

Better use of strategic information is required in the preparation of national plans

In the initial stages of HIV epidemics in Asia, incomplete or unreliable HIV and behavioural data made it difficult to identify the most effective interventions, pinpoint areas where interventions should be concentrated, and deploy resources efficiently. As a result, programming priorities and spending decisions have not always matched the epidemiological realities in countries. In some places, a patchwork of interventions has emerged. In other cases, although apparently comprehensive strategies were devised that sought to address every facet of the epidemic, these stretched resources and capacity so much that the results were disappointing.

Used effectively, strategic information can have a powerful impact on the epidemic. In Thailand, for example, following the analysis of high-quality information on HIV transmission patterns and trends, the identification of epidemic 'hotspots' and their associated risk behaviours laid the basis for a focused and highly effective response.8

HIV data collection has improved in several Asian countries over the past decade, and eight countries now have second-generation surveillance8 (Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Nepal, the Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam). Unfortunately, the push for such surveillance still tends to come more from external donors than national agencies. While several international agencies provide country level HIV projections, only five countries (Cambodia, Indonesia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Viet Nam) generate their own projections, and only three countries (Bangladesh, India, and Indonesia) have information that makes it possible to prioritize and focus interventions at the sub-national level.

Once collected, high-quality HIV information needs to be analysed before it becomes useful for policymaking and programme design. The systems and capacity to analyse the information and channel those findings into policymaking still pose a challenge in many countries, although Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Nepal, and Viet Nam are among the countries that have strengthened their capacity to meet the challenge.

Some national strategic plans are skewed towards treatment provision. Others fail to give priority to those groups most at risk of infection; still others lack comprehensive plans for antiretroviral treatment and impact mitigation programmes in high prevalence areas.

The right focus and a supportive environment are essential for effective programmes

Even when those groups most at risk are identified as a priority for prevention, Governments must ensure that an effective approach is adopted. In many cases, efforts to mobilize strong leadership and resources are later undermined if the interventions fail to reduce HIV risk and transmission in the targeted groups.

For example, in the first reporting phase on progress in reaching the UNGASS targets, one country reported that 80 per cent of injecting drug users were being reached with HIV interventions. In reality, these so-called HIV interventions entailed massive arrests of drug users, partly in the hope that confinement in correctional institutions would force them to abandon their risky behaviour. There is no evidence anywhere that such tactics have such an effect. By contrast, there is ample evidence that access to clean needles and drug substitution programmes do reduce risky behaviour.

A review of country programmes reveals considerable room for improving services for most-at-risk populations.

Currently, only four of the 11 countries in Asia with HIV epidemics among injecting drug users are providing both needle exchange and drug substitution services through Government-funded outlets—and only two of those involve peer outreach programmes. Among countries with HIV threats in the sex trade, only five have introduced peer education programmes, and only two have launched nationwide information and education campaigns that target sex work clients. Few countries are devoting significant resources to interventions for men who have sex with men.

The above observation raises the issue of resource allocation for effective and large-scale interventions. Almost all countries in Asia have national strategic plans that recognize specific high-risk behaviours, but only four of those plans address all three groups that are most at risk, and none contains all of the effective intervention elements described above. In particular, the element of 'enabling environment' is currently missing from almost all focused interventions for most-at-risk groups.

Implementing strategic plan calls for strong management and adequate resources

Even the best-designed programmes are difficult to implement if they lack supporting operational, management, and financing plans. In this respect, there is much room for improvement.

Among countries that have designed plans for effective interventions, for example, only six have costed those plans. Consequently, most countries in Asia cannot currently guarantee sufficient programme coverage, adequate financial and human resources, or reliable procurement processes for the various drugs and prevention commodities that are needed.

A case study from China illustrates the problem. The country's HIV programme mobilized significant funding and other resources, and engineered the necessary changes in the judicial and public health systems to establish more than 1,000 methadone substitution and needle and syringe exchange sites. Nevertheless, despite the best efforts and highest commitment from the Government, the programme missed its coverage target at the end of 2006 by 20 per cent, mainly because the plan was not underpinned by the necessary human resources and because operational planning and preparations were poor.

Cambodia, on the other hand, has shown that adequate operational planning and finance can enable a rapid scale-up. Despite both economic and infrastructural obstacles, the Cambodian Government has been able to effect a significant improvement of its testing and treatment services.

Monitoring coverage of HIV programmes is important to highlight gaps

Coverage ranks high among the several yardsticks for measuring the effectiveness of HIV programmes. In the kinds of HIV epidemics that predominate in Asia, substantial coverage is particularly required in four areas:

• HIV prevention information and services for most-at-risk populations;

• provision of antiretroviral treatment including to HIV-positive pregnant women for prevention of mother-to-child transmission; and

• impact mitigation activities for poor and vulnerable people and households (including widows and orphans).

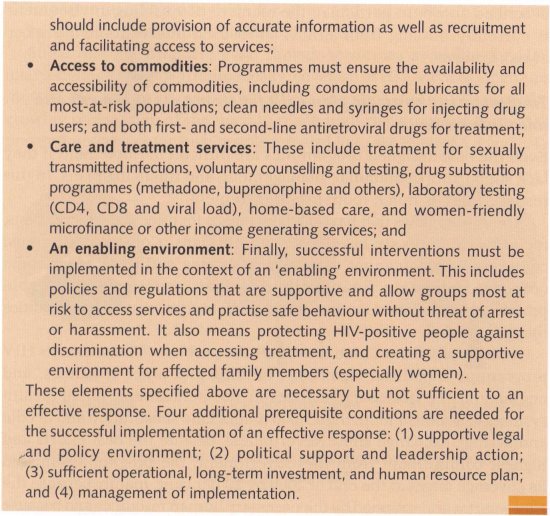

Since the late nineties, even though resources available for HIV interventions have grown dramatically, coverage of HIV services for groups most at risk has remained more or less stagnant in Asia. Despite the growing recognition of the need to reach high-risk groups, coverage of prevention services for such people remains low (see Figures 5.3 and 5.4).

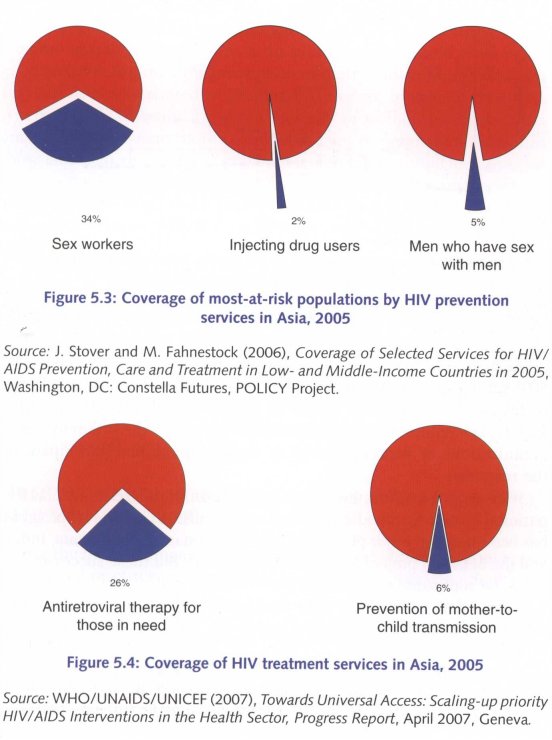

To reverse the epidemic, it is necessary that effective prevention services reach a critical mass of people who are most-at-risk of HIV infection. That threshold of coverage is estimated to be in the region of 80 per cent as shown in Figure 5.5•10 Yet, coverage levels are still a lbng way short of that target.

As discussed in Chapter 4, the availability, accessibility, and use of HIV services by groups most at risk of infection depends on a range of factors, including the levels of stigma and discrimination in a society, law enforcement policies and practices, and the extent to which organizations or representatives of those populations participate in the response.

With regard to commercial sex, in addition to progress made at the national level in Cambodia and Thailand, significant local-level progress has been made in other places (for example, Sonagachi in Kolkata, India, and the SHAKTI project in Dhaka, Bangladesh). But these successes are yet to be replicated successfully on a national scale.

Across Asia as a whole, only about one in three sex workers were being reached by HIV prevention services in 2005, while only one in 50 injecting drug users and about one in 20 men who have sex with men had access to prevention services. Indeed, successful programmes for men who have sex with men are scarce in Asia.11 Yet the exceptions, such as the AKSI Stop AIDS project in Jakarta (Indonesia), have shown how effective such interventions can be.12

Meanwhile, about nine out of ten pregnant women in the region are not being reached by the prevention of mother-to-child transmission services. In some countries, this is partly attributable to the lack of institutional services for pregnant women generally. Countries where women attend antenatal clinics on a large scale should have made good progress in providing prevention of mother-to-child transmission services as demonstrated in Thailand. However, in several countries where antenatal facilities reach a majority of women (such as China and Indonesia, where more than 90 per cent of pregnant women use those facilities), the uptake of prevention of mother-to-child transmission services has barely reached 2 per cent.13 In addition, countries where most deliveries occur outside the formal health system (such as Cambodia, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, and Nepal), service provision remains poor.

Lower prices for antiretroviral drugs and increased external support for their provision has helped change the HIV landscape in many countries, and has potentially transformed AIDS into a manageable chronic disease. A few countries, notably Cambodia, have used these opportunities to expand HIV testing, treatment, and care provision. But. despite the comparatively small numbers of people in need of antiretroviral treatment in Asia overall, few other countries have followed suit. As a result, only about one-fourth of the people in need of antiretroviral treatment in Asia are receiving it.

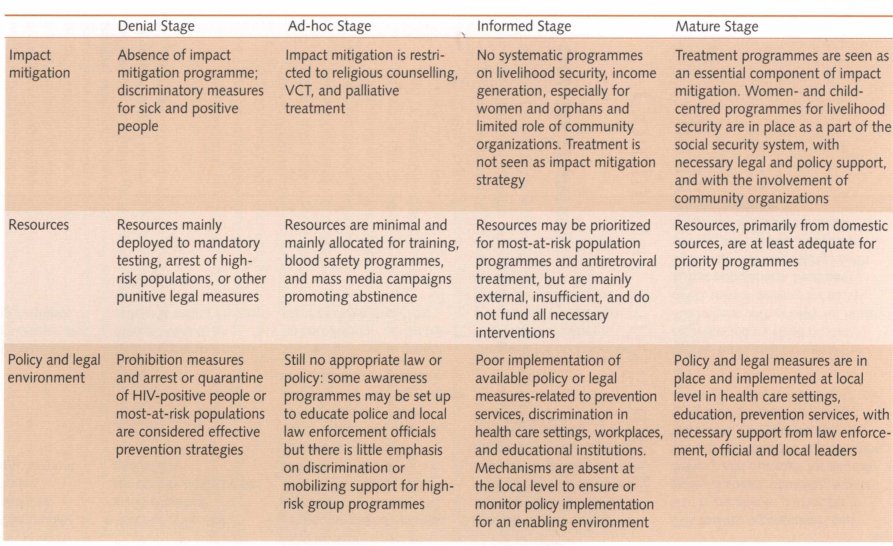

URGENT NEED: MORE RESOURCES AND MAKING THE MONEY WORK

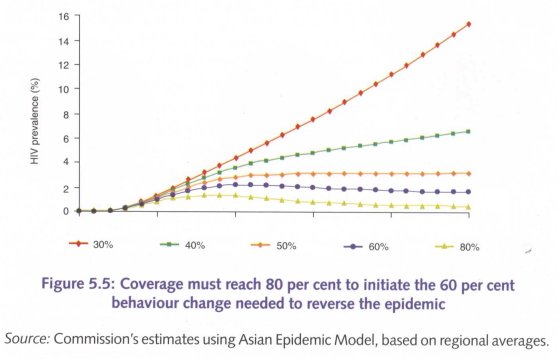

One of the major changes in the past decade has been the vast increase in financial resources now available to countries for fighting their HIV epidemics; much of it available via the Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria, and the World Bank, as well as bilateral funding agencies.

Nevertheless, domestic investment has not increased at the same pace. The Global Fund, for example, has approved more than USD 600 million for 18 Asian and Pacific countries, with the bulk of the funds earmarked for AIDS programmes. The Gates Foundation is investing more than USD 200 million in India, while in the UK, the Department for International Development (Df1D) has committed an additional USD 45 million to aid Indonesia's HIV response. At the same time, domestic spending on HIV-related programmes in Asia has increased at a slower rate than in other regions.

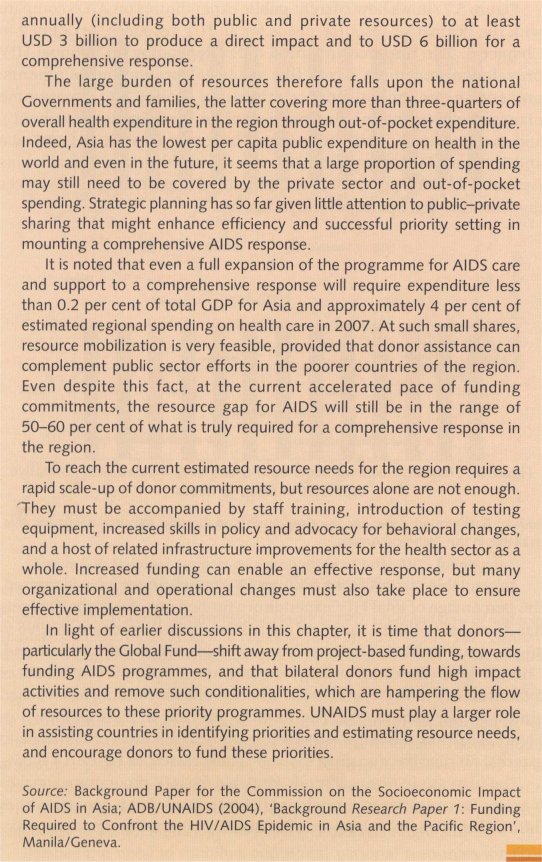

Figure 5.7 shows how current public expenditures on AIDS compare with the normative resource needs for an HIV response, as defined in Chapter 3. The resources required differ depending on national HIV prevalence and must cover five essential programme elements: prevention, treatment, impact mitigation, policy and programme management (including the creation of an 'enabling environment'), and monitoring and evaluation. Even in countries such as Cambodia and Thailand, HIV expenditure still falls short of the estimated amounts needed to fund full prevention, treatment, and impact mitigation services that can curb the epidemic and its impact.

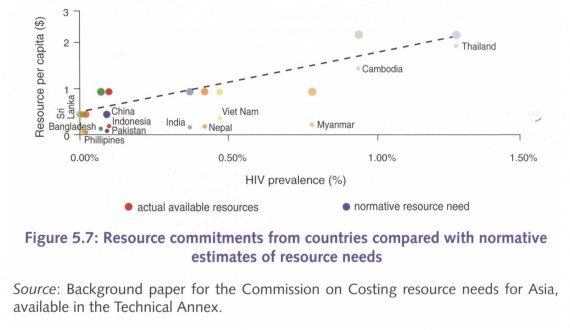

As available resources for funding HIV programmes have increased, the percentage of total HIV expenditure funded out of national budgets has decreased in the 14 surveyed countries—from 60 per cent in 1996 to 40 per cent in 2004. There are two notable exceptions to this trend: China, where domestic funding now accounts for almost 60 per cent of total AIDS expenditure, and India, where domestic funding has reached almost 50 per cent in 2005 (up from 10 per cent in 2004 as shown in Figure 5.8).14 In the other surveyed countries, the ratio of domestic to external funding has remained the same or decreased, as Figure 5.4 shows.

The increase in external funds available for HIV programmes makes it easier for countries to fund their HIV responses. But it can pose other difficulties. Medium- to long-term sustainability of some programmes may be compromised if these programmes are dependent on funding flows that are not controlled by national Governments. External funders might also target programme areas that do not correspond to countries' own priorities. Reporting obligations and lines of accountability can become unnecessarily complicated, and even muddled; governments' ownership' and sense of responsibility for their HIV responses might suffer.

Besides the need to mobilize additional national resources for HIV programmes, it is necessary to ensure that available resources (external and domestic) are used to maximize effect. At the very least, this requires that funding priorities match the patterns and trends of the epidemic. Here, too, countries in Asia have an opportunity to improve their performance.

Donor funding sometimes does not reflect or fit well with the national (or sub-national) priorities laid out in countries' national strategic plans. Donors sometimes select and fund projects in ways that lead to disjointed and duplicated interventions. A Global Fund (Round 6) grant to Bangladesh, for example, provides USD 40 million for awareness education for young people, while peer educators for sex workers (who could prevent a much larger proportion of new infections) have been left without funds due to lack of donor interest.15

Donors should align their funding strategies to an empirically sound understanding of what interventions are most likely to have the greatest impact in preventing HIV infections, treating people living with HIV, and mitigating the epidemic's impact. Guidelines for assigning relative priority of interventions, according to epidemiological and other local evidence, are provided in Chapter 2.

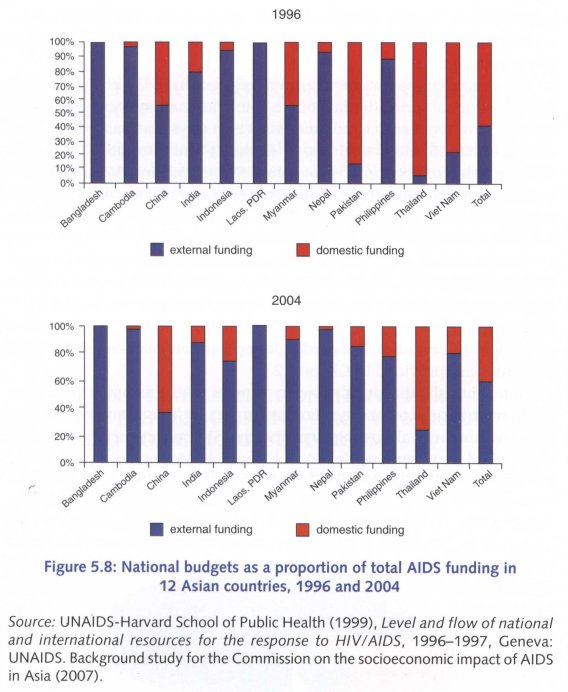

Note, though, that it is not only donors who mismatch resources against strategic priorities. For example, in Thailand, where the Government funds almost 80 per cent of the HIV budget, there is a marked bias toward treatment, as shown in Figure 5.9. More recently, Thailand has been working to revitalize its prevention efforts and mobilize additional prevention funding.

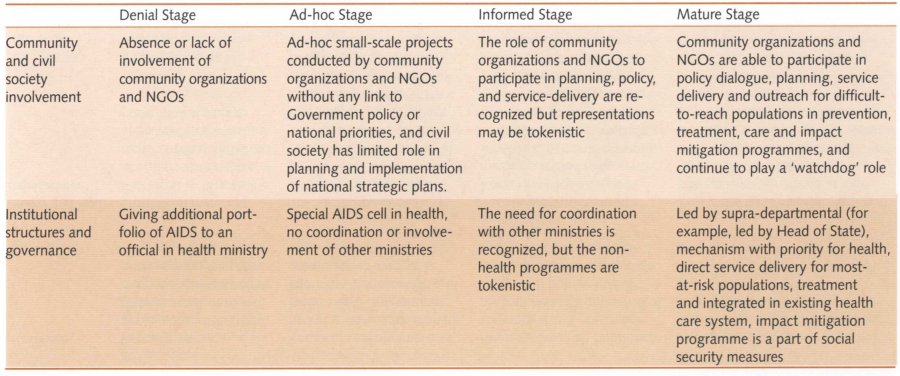

CIVIL SOCIETY AND COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT IS CRITICAL

It is widely accepted that national HIV responses tend to be strengthened when community-based and non-governmental organizations are able to participate in policy development, programme planning, and implementation. Cambodia, India, and the Philippines are among the countries that offer tangible evidence for this proposition. But the opportunities for genuine community participation in HIV responses in Asia remain mixed. Occasionally, communities are able to exert some influence on the response, but often their participation is nominal. The importance of community involvement and examples of their successes in the region are discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

POLICY AND LEGAL ENVIRONMENTS FOR HIV-POSITIVE PERSONS AND GROUPS MOST AT RISK NEED TO BE MORE SUPPORTIVE

Malaysia's decision in 2005 to support harm reduction was in keeping with a trend in Asia toward adopting HIV strategies that are informed by the specific characteristics of their own countries' HIV epidemics—even when such choices might seem politically difficult. China, Nepal, and Indonesia are also part of this trend, and now make harm reduction services available to injecting drug users. This shift is welcome, though not yet ideal. In China, needle exchange and methadone substitution are not available in the same locality; substitution in Nepal is very limited; and Viet Nam's programme is still in the initial phases.

But prejudice remains against groups most at risk and is embedded in laws, policies, and the operational guidelines of law enforcement agencies. Reports of harassment of men who have sex with men, sex workers, and drug users are common across the region16 and in many countries, these populations experience a corresponding lack of access to appropriate HIV prevention, treatment and care services. Indeed, in most Asian countries, sex work, drug use, and sex between men remain criminalized activities.

Sodomy laws for male-male sex remain on the statute books in twelve countries in the region (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Singapore, and Sri Lanka) 17 Sex work is licensed only in limited settings within Singapore and the Philippines. Advocacy to amend or relax such laws remains weak, as does the appetite of political leaders for taking up these issues. This poses a problem. The criminalization of these risk behaviours can effectively neutralize otherwise supportive HIV policies—unless the cooperation of law enforcement agencies and the judiciary can be achieved. Such a feat requires methodical and patient liaison work and bridge-building, and is more likely to be achieved if underwritten by strong support from the highest levels of Government.

In addition, only three countries (Cambodia, Philippines and Viet Nam) in Asia have introduced laws that specifically seek to protect the rights of people living with HIV and guard them against HIV-related discrimination. Another five (Bangladesh, China, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, and Singapore) have announced policies that explicitly protect the rights of HIV-positive people.

INSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURES AND GOVERNANCE ARE STRONG DETERMINANTS OF AN EFFECTIVE RESPONSE

National HIV responses in Asia have evolved amid shifting Government priorities, changing perceptions of the epidemic, and the emergence of a range of HIV stakeholders and partners. As a result, unity of purpose, policy clarity, and harmonized action have suffered. Ibo often the various actors involved are not operating in a harmonious fashion. The 'Three Ones' principle arose in response to this problem and is aimed at achieving the most effective and efficient use of resources and to ensure more rapid action. It calls for:

• one agreed HIV Action Framework that provides the basis for coordinating the work of all partners;

• one National HIV Coordinating Authority, with a broad-based multisectoral mandate; and

• one agreed country-level Monitoring and Evaluation System.

At the core of this approach is the recognition of how important coherent national leadership and ownership is for sustainable and effective national HIV responses.

In Asia, as elsewhere, Governments have tried to improve their ability to manage HIV programmes that have become increasingly complex (partly because of the involvement of so many national and international partners). While Ministries of Health continue to play a central role in the health sector response (partly in keeping with the importance of antiretroviral treatment programmes and associated prevention opportunities), other sectors have moved centre-stage, as well. This emergence of broad-based, multisectoral responses, coupled with the growth of external finding (and partners), underlines the need for effective national coordination.

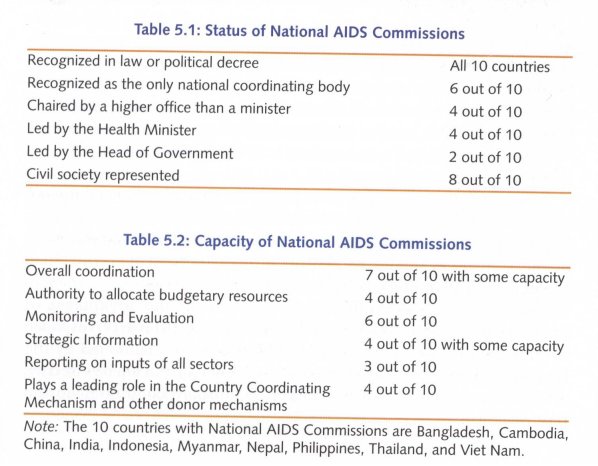

In theory, National AIDS Commissions are the preferred candidates for that role—and many countries in Asia have established such bodies. But a brief overview of the 10 Reports by UNAIDS Country Offices shows that their political status, authority, capacity, and responsibilities vary greatly, as seen in Tables 5.1 and 5.2 below.

Such variation raises important questions about the role and responsibilities of national coordinating bodies in Asia's HIV responses. Does one model of national coordination and oversight fit all the different political and administrative structures in various countries? Are National AIDS Commissions always the ideal coordinating structure, or are there alternatives that may be better suited? What should be the primary role of National AIDS Commissions? Who should lead such a coordinating body, and what are the (dis)advantages of placing the Ministry of Health rather than, say, the Planning Ministry or Office of the Head of Government at its helm?

It does seem clear that the role of National AIDS Commissions should be limited to policymaking, coordination and monitoring and evaluation of the response, and that they should not be directly involved in direct implementation or service delivery.

But there is no one-size-fits-all answer to these questions. Countries need to face up to these problems and to devise options that best suit their respective political framework and priorities. In other words, what is needed is an in-depth assessment of existing National AIDS Commissions in the context of the differing epidemiological, social, and political contexts.

A review of experiences to date suggests that, as a provisional rule-of-thumb:

• the Health Ministry should be 'first among equals' in the National AIDS Commission;

• the National AIDS Commission needs to decide which entity should act as its Secretariat. Often the Health Ministry would be well-suited for that task;

• only ministries with direct involvement in the HIV response (for example, Ministries of Education, Police, Justice, Social Welfare) should sit on the National AIDS Commission;

• these ministries should allocate some of their own funds and incorporate HIV components into their programmes to ensure their involvement in and commitment to the response; and

• strong coordination is essential.

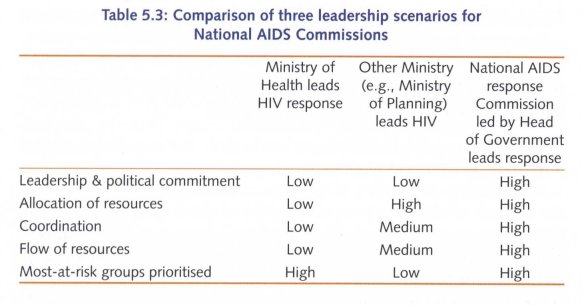

Who should head this structure? The Commission has compared the potential effectiveness of National AIDS Commissions in three different hypothetical scenarios: National AIDS Commissions are led by the Ministry of Health, by another Ministry outside of Health (such as Finance or Planning), or by a Head of Government.

The findings (shown in Table 5.3) highlight the advantages of ensuring that overall responsibility for managing the HIV response is vested with a strong National AIDS Commission that is led by the Head of Government. But such an arrangement appears to be effective only when the Head of Government is strongly committed to the HIV response.

The Commission also reviewed the programme implementation mechanisms at the national level. It found that many of them are headed by technical personnel from Health Ministries who are not always well-positioned at the decision making level. In some countries, programme managers have to pass through three or four levels of administrative hierarchy to reach a decision making level. Frequent personnel changes also undermine the continuity of programme leadership and hamper the effectiveness of programmes.

Currently, only India has been successful in assigning leadership of the programmes to a senior level functionary in the Government; where this has been done, it has proved to be highly successful.

An important governance structure which has evolved over the past five years is the Country Coordinating Mechanism of the Global Fund for AIDS, TB, and Malaria. While Country Coordinating Mechanisms in Asia have been fairly successful in compiling strong funding proposals, the implementation of the programmes has been poorly monitored.

Although the Country Coordinating Mechanisms are meant to act as multisectoral bodies with strong civil society representation, most of them are dominated by Health Ministries. Civil society representatives in many countries feel left out and complain about the lack of scope for meaningful participation. Even non-health Government structures appear not to participate effectively in the Country Coordinating Mechanisms.

The Commission is strongly of the view that the establishment of good governance structures for policy, planning, implementation, and coordination of AIDS programmes is a prerequisite for an effective response. Weak governance structures lead to skewed priorities and lopsided allocation of resources, in turn leading to ineffective service delivery and an accountability vacuum.

FOR TECHNICAL SUPPORT, THE UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM SHOULD DELIVER AS ONE

The HIV responses in Asia have evolved in the context of several important global developments.

One was the emergence of highly-active antiretroviral therapy, and the success of efforts to lower the prices of those drugs, which made HIV treatment an increasingly affordable component of national HIV responses. The second was the dramatic increase in donor funding for HIV programmes, principally via the Global Fund (to fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria), the World Bank, and the Department for International Development, the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief,18 and several large private foundations.

Thirdly, several other initiatives have served as the backdrop for countries' attempts to enhance and consolidate their HIV responses. These have included the UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/ AIDS (UNGASS) Declaration of Commitment in mid-2001 and its follow-up processes, the ongoing Millennium Development Goals campaign, the '3 by 5' treatment initiative, and the push to achieve Universal Access to prevention, treatment and care services.

These developments have spurred greater efforts (especially on the part of United Nations agencies) to craft, cost, and implement comprehensive national HIV strategic plans based on quality HIV data and analysis.

The strong global advocacy of UNAIDS has had a positive impact in Asia, by spurring a significant increase in resources for HIV and in strengthening the political commitment of Asian leaders for their respective HIV responses.

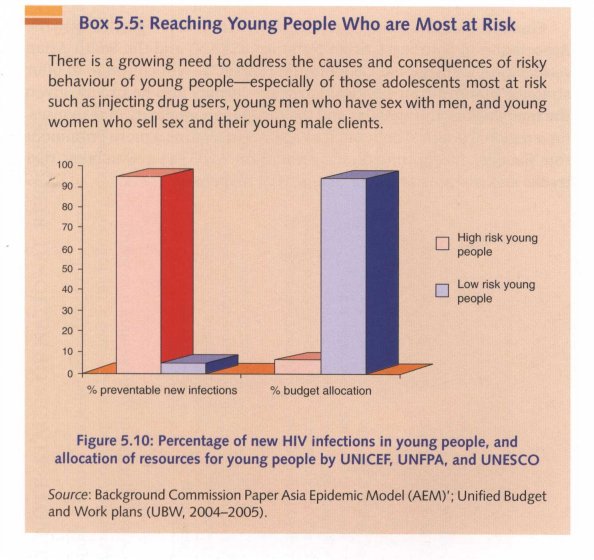

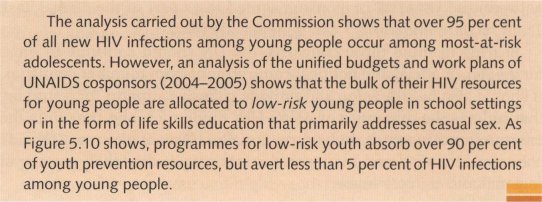

However, the Commission is concerned that UNAIDS has not always been effective in facilitating well-integrated support to countries—largely due to the duplication of effort and at times disjointed activities on the part of the UN agencies (see Box 5.5). Because some programmes reflect the corporate priorities of respective UN agencies (rather than those of UNAIDS or the affected countries), the HIV support programmes often lack coherence. It is still unclear whether the division of labour between the UNAIDS cosponsors agreed to as part of the Global Task rlbarn recommendations19 can be realized effectively.

Bearing in mind those concerns, the UN should continue to press for greater financial and political commitment from member countries. It should also help develop and provide cohesive support for a strategy that reflects the dynamics of Asia's HIV epidemics, and that suits the environments in which they occur. Equally, UN agencies must provide coherent technical and managerial support to realize that strategy at regional and country levels.

Finally, Asia's regional intergovernmental bodies—particularly the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC)—will continue to offer strategic platforms for political advocacy. It may also be timely, given the many actors and agendas and the resultant complexity of responses, for a regional political body such as ASEAN to assume a more prominent role (besides its continued engagement on AIDS) as a 'watchdog' that tracks and assesses Member States' HIV responses.

1 'WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF (2007), 'Ibwards Universal Access: Scaling up Priority HIV/ AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector, Progress Report, Geneva: WHO.

2 The Thai 'health security scheme' provides universal coverage of health care services; for more information, please see National Health Security Office (http:// www.nhso .gov.th).

3 National surveillance data published by Bureau of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, HIV Serosurveillance in Thailand, December 2007, Bangkok.

4 1n Figure 5.1, the black lines depict this variability, while the small blocks reflect the Commission's overall assessment of the country's response—in this case 'Mature'.

5 The UNGASS Declaration, signed at the UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS in 2001, was a commitment to prevention, treatment and care, and accelerated research to achieve the Millennium Development Goals of halting and reversing the spread of HIV by 2015.

6 The Universal Access initiative arise from the UN General Assembly's 2005 High Level Meeting on AIDS, where the Political Declaration commits to set ambitious national targets for prevention, treatment, and care by 2010.

7 The 14-country review includes: Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Viet Nam; the detailed review is available in the Tbchnical Annex.

8 UNDP (2004), Thailand's Response to HIV/AIDS: Progress and Challenges, Bangkok: UNDP.

9 Second-generation surveillance systems refer to the collection of biological (such as HIV and STI prevalence) and behavioural (such as frequency of condom use and safe injecting behaviours) data (risk-behaviour practices, such as frequency of condom use and safe injecting behaviours).

10 Modelling (using AEM and HIV Tbolkit) indicates that about 60 per cent of mostat-risk populations need to adopt safer behaviours if HIV epidemics among them are to be reversed, and service coverage has to reach about 80 per cent for that level of behaviour change to occur.

11 J. Stover and M. Fahnestock (2006), Coverage of Selected Services for HIV/AIDS Prevention, Care and D'eatment in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in 2005, Washington, DC: Constella Futures, POLICY Project.

12 UNAIDS (2007), 'Men who have sex with men: the missing piece in national responses to AIDS in Asia and the Pacific', Bangkok: UNAIDS RST-AP.

13 WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF (2007), Tbwards Universal Access: Scaling up Priority HIV/ AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector: Progress Report, Geneva: WHO.

14 Although the 2004 data given represents AIDS expenditures, the references to India and China are based on resource allocation estimates after 2004.

15 Based on the Commission's findings, which are discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

16 C Jenkins and S. Sarkar (2007), Creating environments that care: interventions for HIV prevention and support for vulnerable populations: focus on Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok: Alternate Visions.

17 Douglas Sanders (2006), 'Health and rights: human rights and interventions for males who have sex with males', available at:

18 In Asia, PEPFAR funds have benefited mainly one country (Viet Nam).

I9 The Global Task "'barn was formed to improve coordination among multilateral institutions and international donors to further strengthen the AIDS response. More information on the Global Task Tbam and its recommendations are available at MoneyWork/GTT/ default.asp

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|