4 The Cultural Context

| Books - Narcotics Delinquency & Social Policy |

Drug Abuse

IV The Cultural Context

We have already established that juvenile drug use is not randomly distributed over New York City. It is heavily concentrated in certain neighborhoods. These are not a cross-section of the city's neighborhoods, but rather they are the ones which are economically and socially most deprived. Even within the relatively few tracts in which we found the vast majority of cases, the tracts of highest drug use can be distinguished from those with lower rates of juvenile drug use by a variety of social and economic indexes. The tracts with the greatest amount of drug use are those with the highest proportions of certain minority groups, the highest poverty rates, the most crowded dwelling units, the highest incidence of disrupted family living arrangements, and so on for a number of additional related indexes.

Now, we can think of no good reason why economic squalor per se should lead teen-aged boys and young men to use drugs. Presumably, the effects are indirect, mediated by certain attitudes and values which are generated in such environments and which, in turn, predispose the youth to experiment with narcotics. In the preceding chapter, for instance, we suggested that conditions of economic squalor may generate a sense of hopelessness from which narcotics offer at least a temporary, if illusory, escape. Yet, such an hypothesis sounds naïve, even to us, as applied to the youths.

It might be credible if applied to adults who, after years of futile struggle, simply give up. But what can a youngster have known of futile struggle against the misery of economic deprivation? He may have known the misery itself. He may have shed bitter tears in the extremity of his wants, he may have protested and demanded in vain efforts to bring the world to his terms; he may have, without thought of right or wrong, taken things that attracted him but to which he had no right, only to learn that such taking is likely to bring with it dreaded punishment. But why should he have already given up? Why should he not have been persuaded by the implicit and explicit teachings in his school review of American history of the reality of the American Dream? Why should he not have been persuaded by the glimpses of a better life in the movies and on television, by the sheer volume of beckoning advertisements, by the store displays, by the evidences of conspicuous consumption, and so on that these things are available to him if he but strives hard enough?

If he is oppressed by a sense of futility, where can he get it but from the culture around him, a culture that is more powerful in the concreteness and immediacy of its lessons than the shadowy glimpses and the idealized verbalizations of the achievability of a better life? Where but from his vicarious experiences, the evidences of frustration and failure and of the acceptance of defeat that impinge on his senses? Where but from the expectations and evaluations expressed by those about him who speak with the authority of participation in the world of his direct experience?

He,does not need to have himself worn away a lifetime of days in futility to be convinced of its reality. And, if the eloquence of his school books and teachers and the dramatizations of the mass media and their appeals nevertheless bring the American Dream into his life space, is it not as dream? Is it not as reality for others, but as a fantasy world for him and others like him? What better foundation can be laid for a willingness to experiment with the alchemical stuff that offers the promise of transforming the fantasy, for a while at least, into an isotope of reality?

These remarks on the sense of futility are intended only as an illustration of how the relation between economic squalor and drug use might be mediated by a process of attitude formation. If they sound convincing, we still cannot but pause and wonder whether they are true. Plausibility is not a satisfying substitute for evidence. If the conditions we have reported as associated with drug use actually are mediated by the formation of certain attitudes and values, we ought to be able to demonstrate the latter directly. We wanted to know whether there was anything about the social climate, the culture, the ethos-call it what you will—that might make one neighborhood more hospitable to experimentation with narcotics than another.

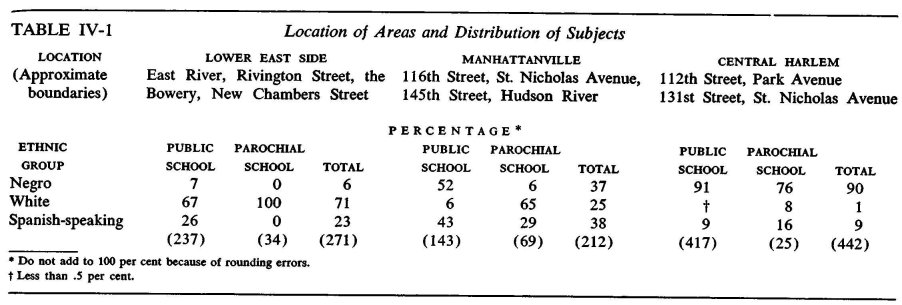

Practical considerations made us curb our ambitions. We had to limit ourselves to three comparable neighborhoods differing in the known incidence of juvenile drug use—one very high, one medium, and one relatively low but where drug use is reputedly increasing.1 We also limited ourselves to all of the eighth-grade -boys attending the four junior high schools and the seven parochial schools servicing our three neighborhoods.2 This decision was guided by the reasoning that, on the one hand, the elementary and junior high schools provide easiest access to a relatively unbiased population (the lower the grade level, the more unbiased) and that, on the other hand, eighth-grade boys are approaching the age at which we had found that significant numbers of teen-agers begin to try drugs. Our working hypothesis was that at this level we would already find constellations of attitudes, values, and information or misinformation about narcotics that would help to explain why differing proportions of these boys will, in a few years, probably be willing to try drugs.

It should be apparent, however, from what has already been said about neighborhoods which differ in incidence of drug use, that, though our three neighborhoods may be relatively comparable—e.g., all three are lower-class neighborhoods—they nevertheless differ markedly in many respects: average income, ethnic composition, and so on. High has higher delinquency rates than Low, but all three neighborhoods have quite high delinquency rates.3

We used a questionnaire tapping a variety of attitude, value, and information areas that we thought relevant to our problem. Fifty-one items had no specific reference to drug use. Eleven of these called for certain background information, for instance, whether the respondent was living with his father. The remaining forty ranged over the following topics: attitudes toward police, attitudes toward parents, agreement or disagreement with certain middle-class standards of behavior, personal feelings of optimism, evaluation of certain life goals, and adaptations of the items used by Srole4 in his scale of anomie. The anomie items try to get at a lack of trust in people, a pessimistic outlook toward the future, and a sense of futility. Forty-five items were explicitly related to narcotics and were divided among the following topics: attitudes toward the use of drugs, image of the drug-user, action orientation with regard to the drug-user, evaluation of arguments against using heroin, information or beliefs about drugs, and personal exposure to the use of heroin.

The questions were cast in as simple a form as possible because we had to meet the reading level of the poorest students. As an added precaution, the questionnaire was administered item by item, the teacher reading the items one at a time to each class. Responses consisted of checking one of two or, in some instances, one of three alternatives. The replies were anonymous. The questionnaire was administered in two parts in two class sessions.3

We made several checks on the answers the boys gave, and we are satisfied that they are not random and that they are not merely socially approved responses.

If the boys simply gave approved responses, we would expect that high proportions of the subjects would consistently give what seemed the desired responses to the items. This, in general, was not the case. Not only do the proportions of "right" responses, let us call them, vary considerably from item to item, but, surprisingly (from some points of view, distressingly), high proportions give the "wrong" responses to many of the items.

Thus, two of the items ask what should be done if "you find out that one of the boys on your block is using heroin." In nine of the eleven subgroups formed when we classified the boys by neighborhood, ethnic or racial identification, type of school attended, and type of class6—in nine of these eleven subgroups, about 40 per cent agreed with the statement: "Nobody should do anything. It is his own private business." In one subgroup, the proportion agreeing with this statement was as high as 57 per cent and, in one subgroup, only 13 per cent. In all eleven subgroups, about 47 per cent did not agree that one should "tell the school or the police about him."

Similarly, from about 43 per cent to 63 per cent of the respondents in the various subgroups agreed with the statement that "the police usually let their friends get away with things." And from 33 to 83 per cent agreed that "most policemen can be paid off." Or, to take still another illustration, about 39 per cent of the boys in each of the subgroups in High said "Yes" to the question, "Did you ever see anybody taking heroin?" The corresponding figure for Medium was 24 per cent and, for Low, 13 per cent. Forty-five per cent of the respondents in

High claimed personal acquaintance with a heroin-user, 32 per cent in Medium, and 17 per cent in Low.7

One may, of course, suppose that there is a considerable bloc of pupils who gave what they conceived as "proper" answers and possibly a second bloc who mischievously took advantage of anonymity by giving "improper" answers whenever they spotted an opportunity to do so. The effect of such blocs would be to make for fairly high correlations among the items. This, in general, did not prove to be the case.

We must anticipate somewhat to explain the data. We computed tetrachoric correlationsa among the items separately for the three neighborhoods. In a few instances, several items with related content were combined into indexes in order to avoid extreme marginal breaks' or for other reasons; the distributions for these indexes were dichotomized and the resultant dichotomies used in the computation of tetrachoric coefficients. Counting these indexes as individual items and dropping some of the personal data items, we were left with seventy-two items among which all of the intercorrelations were computed-2,556 correlation coefficients for each neighborhood.

About 20 per cent of the correlations in Medium were statistically significant,' about 25 per cent in Low, and about 30 per cent in High. In other words, from about 70 to 80 per cent of the correlations were not statistically significant, a finding which is hardly compatible with the hypothesis of blocs of consistently conventional and consistently nit-conventional respondents.

This finding, however, may seem to support the possibility that the responses are random. Actually, the figures just quoted would be sufficient to controvert this hypothesis, since the numbers of statistically significant correlations, though small, are nevertheless considerably greater than could reasonably be expected by chance. It should be remembered, in this connection, that the questionnaire was designed to cover a wide variety of attitudes, values, and information. On this basis, it would be surprising indeed (and probably explicable only by some such hypothesis as the one we have already discarded) if a very high proportion of the interitem correlations proved significant. Apart from the sheer number of significant correlations, we are in a position to make a minimum estimate of the reliabilities of the individual items.d Such a minimum estimate can be obtained by taking the highest correlation between a given item and any other item as a measure of that item's reliability. When this is done, we find that the median item reliability in the low-drug-use neighborhood is above .50 and, in the other two neighborhoods, above .55—a high order of reliability for single items and quite incompatible with the random-response hypothesis.

Finally, we may mention that we computed for another purposee the correlations between the correlational profiles of the items. That is, a given item will correlate relatively high with some items, relatively low with others, negatively with still others, and so on; a second item may have a similar correlation profile or one that is quite different. The degree of similarity between profiles can be measured by the correlation between them. The general level of these second-order correlations runs considerably higher than the tetrachoric correlations we have been discussing. Such a result would indicate an underlying structure to the patterns of response, some aspects of which we will discuss below. Of immediate relevance, however, is the fact that this structure is a meaningful one, and meaningful structures are hardly likely to appear if responses to items are arbitrary or capricious.

Granted, however, that the boys have, by and large, taken the questionnaire seriously and attempted to set down in response to each item their true thoughts and feelings, it still does not follow that we can take these responses at face value. The process of communication is replete with ambiguities and sources of mutual misunderstanding even under the best of circumstances—when people are talking to one another face to face, in a position to respond to facial and bodily expressions and to vocal intonations as well as to words, when the content of the communications can be amplified or repeatedly paraphrased as one'person senses the needs of another, and when the continuation of the process itself provides checks and cues as to the messages that get across. In a questionnaire situation, none of these conditions exist,8 and what looks like a simple "yes" or "no" to what looks like a simply worded item may be an extremely complex psychological event. Consider, for example, the following item: G 26. "Most addicts who take the cure never go back on drugs again." The respondents were asked to check, "True," "False," or "I don't know." The second is factually correct,9 and this item was one of a series designed to get a measure of the prevailing level of information in each of our three neighborhoods on matters pertaining to drugs.

Let us note that no eighth-grade boy can be expected to know the correct answer to this item in the same sense that, say, a psychiatrist who has been trying to treat addicts for many years may be expected to know it. At best, our young respondent will have heard relevant statements from sources to which he reacts as more-or-less credible; he may have direct personal knowledge of a case or two. He will have accepted the correct version with more-or-less assurance and will therefore be more-or-less inclined to say "false" to the item as presented.

But many other influences may bear on the determination of the response that he finally makes. He is, for instance, more-or-less confident that his inclination is correct. How confident must he be to draw a dividing line between "I don't know" and one of the definite responses? Individuals differ in this respect. Some will doubtless readily convert a pure guess into an unhesitating, assured response; others will cautiously conceal much more supported opinions behind an "I don't know." That is, we have here a temperamental, or personality, variable in addition to an information variable.

Various attitudes also have bearing on the determination of the response. Take the following item, by way of illustration: G 3. "Heroin is probably not as bad for a person as some people say." At the moment, all that concerns us is the bearing of the reaction to this item on the response to the preceding one. Suppose that a person has come to feel that the effects of heroin are so catastrophic that no one can exaggerate its dangers. With such an attitude, a person who has never considered or heard anything about the effectiveness of the treatment of addiction may, nevertheless, be inclined to assume the worst. To the extent that this is so, choosing the correct response to Item G 26 would be an expression of an attitude rather than of information.

Other determinants of the response have nothing to do with the content of the item, but with the formal properties of the wording. It is known, for instance, that individuals differ with respect to what may be called "gullibility," or "acquiescent tendencies." Some find it relatively difficult to resist definitely worded statements and are inclined to assent to them; others are relatively negativistic, critical, or suspicious of definitely worded statements and, other factors being equal, are inclined to disagree. Moreover, consider a person who is inclined to disagree with such statements. Suppose that, by the time he has gotten to the item we are considering, he has already been confronted with a series of items with respect to which he had little to go by other than this no-saying tendency. By the time he has reached our item, his no-saying tendency may have been thoroughly satiated, and he may have developed quite a tension to say "yes" to something—and our item reaps the benefit. It may be assumed that individuals differ in the readiness with which their yes- (or no-) saying tendencies are satiated; and, even if we could select individuals who are exactly alike in this respect, it seems likely that any specific series of items would produce individual differences in the satiation rates.

There are a number of other factors which can affect how a person answers a particular item at a particular time. The actual answer may be a result of many influences, some of which lead the respondent to agree, some to disagree, and some—if the alternative is available—to say, "I don't know."

It seems clear that, given only the response of a particular person to a specific item, we can know very little about the meaning of the response. Even if we have the responses of many individuals to the same item, we are still in no position to disentangle the individual meanings. We can say how many selected each of the alternatives, but we cannot say whether or in what respect those who selected a given response have responded to the same aspect of the item or given expression to the same aspect of themselves.

As the number of items that comes within our purview increases, however, our situation changes; for, from the way that the responses to many items cohere, we can say something about the prevailing structure of the determinants.

Suppose, for example, that the addiction-cure item, G 26, hangs together with other items designed to get at information; that is, suppose that the answers to this item tend to be related to the answers given to many other items in the same way that the other information items are.

This would support the assumption that the item does, indeed, tend to get at information. In the existence of a cluster of such items, we would have a basis for concluding that there exists an information current in the cultural atmosphere. Some individuals may be more-or-less in the current, some more-or-less out of it. But there is something that brings these diverse items of information together, that makes them relatively equivalent one to another, that establishes them in a functional unity. The nature of the "something" we do not know, and, at this juncture, we do not particular care; what interests us is the existence of the current.

Suppose, by way of contrast, that the information items do not cohere and that the addiction-cure item does cohere with certain attitude items. We might then conclude that the outlook on the cure of addiction tends to be shaped by an attitudinal, rather than an informational, current in the cultural atmosphere. The particular alternatives selected by individuals in responding to the addiction-cure item would tend to be determined by where they stand with respect to the attitudinal complex or to the forces that shape this complex.

We might, of course, find that the addiction-cure item coheres with both information and attitude items, an outcome that would give us still another picture of the bearing of the cultural atmosphere on attitude toward the cure of addiction. Or we might find that the addiction-cute item does not hang together with any others, an outcome that would suggest that the outlook on the cure of addiction is shaped by highly idiosyncratic influences or by cultural influences untapped by our questionnaire.

We have been focusing on a particular item for purposes of illustration. Our interest lies, however, in the identification of the broad currents in the cultural atmospheres of our three neighborhoods, as evidenced by the coherence, or clustering, of the items.

The meaning of item clusters is discussed in some detail in Appendix E, and our reasons for preferring this form of analysis to a more popular type are given in Appendix F. For present purposes, it may be sufficient to indicate that a cluster consists of a number of items, each of which has a pattern of correlation with all the other items that is similar to the patterns shown by the other items in the cluster. The items in a cluster may be said to have similar or closely related implications to the respondents.

Instead of thinking in terms of cultural currents, we may think of a cluster as a group of items providing a crude map of a cultural channel through which certain ideational, attitudinal, and/or valuational issues become linked so that the position that one takes with regard to one or more of these issues is related to the positions that one takes with regard to the others. Issues may become so linked because of their common content; e.g., dislike of the police and tolerance of lawlessness may become linked because they have in common a belief that laws are made for the benefit of others. They may become linked by processes of direct causal interaction; e.g., the perception of police venality may breed disrespect for law, which, in turn, may contribute to selective perception of police activities. They may be linked by historical contingencies—e.g., a minority group may be impressed by its political impotence and regard law as an expression of the will of the majority group (regardless of the merits of the laws per se)—and, at the same time, perceive that most members of the police force are members of the majority group; in this case, the linkage would be a function of the minority-group situation and the crystallization of attitudes and beliefs relevant to this situation.

The linkage in the preceding illustrations between liking or disliking of police and intolerance or tolerance of lawlessness is purely hypothetical, as are the alternate bases of the linkage described. That the conditions of the linkage postulated in these illustrations are not sufficient ought to be clear from the compatibility of these conditions with reversals of the linkage or of their bases. The belief that laws have been enacted for the benefit of others need not be accompanied by tolerance of lawlessness. Many Southerners, for instance, who believe that the Supreme Court decisions on segregation are expressions of Northern and international politics and inappropriate for the South, nevertheless accept the decision as the law of the land and believe that, as long as this is so, it should be observed. One may disapprove of a law, but still respect law enforcement officers for trying to do a good job. The observation of police corruption may serve only to heighten one's sense of the importance of preserving law and order. With respect to minority groups, Kurt Lewin has described the complex phenomenon of self-hatred (and one may also think, in this connection, of the phenomena that Freud has described as identification with the successful rival and identification with the aggressor), in terms of which minority-group members may come to respect the law and its enforcement officials all the more, precisely because they represent the majority group.

Nor is the particular linkage itself, in whichever direction, necessary; one may have an attitude toward lawlessness without ever bringing attitudes toward the police into the same context; or toward the police, without ever thinking in the same context of the importance or unimportance of the preservation of law and order in general and without either condemning or condoning particular instances of lawbreaking in particular. Attitudes toward the law and/or its enforcement officers may or may not be linked to the perception and evaluation of status differentials in society, to other authoritarian or egalitarian attitudes, to religious attitudes, or to whatever. Attitudes toward particular regulations (e.g., those governing automobile traffic or the filing of truthful income tax returns) may or may not be isolated from attitudes toward law in general.

The point is that the conditions governing the linkages of ideas, attitudes, values, and the like are extremely complex. The question of how particular linkages come about may be worthy of intensive research or may constitute fertile ground for learned or entertaining speculation. But, however they may come about, the discovery of linkages in a society or subsociety tells us something about the prevailing culture and the patterns of thought and the like which characterize it. Moreover, once they do come about, they tend to become self-sustaining, regardless of how they may have originated, for they constitute part of the objective basis of the experience of the participants in the culture. In-a sense, these linkages are as much an aspect of the geography of the behavioral environments of individuals as the streets, alleyways, and bridges are of their physical environments. They offer familiar and convenient channels of association and thought and thereby help the individual to interpret and evaluate the things he experiences.

The linkages need not be consciously articulated or put into words. They are implicit in the course of the conversations that one overhears, in the things that people take for granted as they draw inferences, in the choice of figures of speech, and in the patterns of events and the classes of objects that elicit similar reactions—the occasions for laughter, incredulity, cynicism, optimism or pessimism, cursing, blaming, admiring, and so on. The process of internalizing the linkage in one's psychic structure may, of course, be facilitated by the recurrence of conditions that originally gave rise to them or by new conditions that contribute to the same end.

A person who finds himself on one side of an issue is likely to find himself on the corresponding sides of other issues linked to it, even with regard to issues that he may never before have encountered as such. All that he needs are enough cues to place the new issues in his psychic map of the cultural terrain. If unearned sensuous gratification is evil, then, even though he may never have confronted the issue of narcotics before, he need but sense that the taking of narcotics is a means of achieving unearned gratification, and this practice, too, will be tainted with evil. If, on the other hand, the practice of smoking tobacco is already firmly linked to other contexts—say, manliness or the sheer exercise of habit—and there are not enough cues to place tobacco in the context of unearned gratification, then to the same person smoking will not be tainted with evil, even though the man from Mars may find it difficult to distinguish between the two practices.

Needless to say, we cannot hope to explore every aspect of the cultural terrain of the eighth-grade boys in our three neighborhoods. At the most—and this is what we attempted to do in the questionnaire—we can sample from strategically selected sets of issues and try to explore the linkages that exist. The linkages are inferred from the statistical behavior of the items, not so much from the direct correlations between items as from the relationships of each item to all the remaining ones.t

The Delinquent's World View

Turning now to the actual data, we shall first consider the appearance of four clusters, one each in Low and Medium and two in High, which suggést the widespread consolidation of attitudes and values in an outlook favorable to delinquency.

These are sixteen items g common to the four clusters. For convenience, we shall refer to the items by their questionnaire numbers and brief descriptions or paraphrases, wording the latter in the direction of the scoring. Each of the sixteen items correlated positively with each of the others. Similarly, the correlation profile of each item correlated positively with the correlation profiles of each of the others.

Two of the sixteen items expressed attitudes unfavorable to parents:

F 2, 16, 21: Compound item

F 24: Parents always looking to nag

Four of the items expressed attitudes unfavorable to the police:

F 6: Police open to bribes

F 17: Police practice racial discrimination

F 19: Police pick on people

F 23: Police favor their friends

Two of the items expressed rejection of middle-class rules of deportment:

F 7, 13, 26: Compound item

F 9: Shouldn't always treat girls nice

Two of the items involved issues of major values:

F 29: Value power over people

F 39: Value thrills and taking chances

Three items expressed attitudes of profound pessimism and alienation:

F 4: Not much chance for a better world

F 22: Most people better off not born

F 25: Everybody really out for himself; nobody cares

Finally, there are three items which express "wrong" attitudes on issues involving narcotics:

G 1: Heroin use a strictly private affair

G 3, 4, 5: Agree with at least one of the following: heroin not so harmful as people say; taking a little heroin once in a while doesn't hurt; it is OK to smoke marijuana at parties

G 8: Heroin OK if you don't get hooked

A common theme of many of these items is that people do not respect other people, that they are mean and arbitrary in the pursuit ,of their private ends. If this is the premise, it is not difficult to conclude that a major value is the achievement of power and getting other people to do what one wants, that the outlook for most people is indeed bleak, that no one should interfere if people are engaged in illicit or self-destructive behavior, that socially set rules of deportment do not make much sense, and that the most sensible thing a person can do is to seek pleasure and gratification where he can find them.

This is perhaps to put an overly rationalistic construction on this grouping of items, but it seems reasonable to assume that the items cohere on some such basis; they are expressive of a reasonably integrated world outlook.

It does not follow, of course, that everyone in these three neighborhoods shares this philosophy, but that substantial numbers of individuals wittingly or unwittingly orient themselves with respect to such a philosophy. Some accept, some reject, and some waver. If our interpretation of the meaning of a cluster is correct, however, the existence of such a philosophy is an objective fact in the lives of the youngsters of the three neighborhoods.

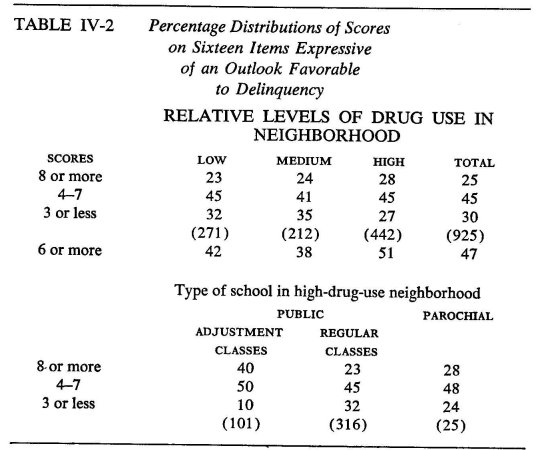

A rough index of how thoroughly such views have seeped into our eighth-grade populations may be obtained by treating the set of items as a test. If each item were scored 1 or zero, the resulting distributions are given in Table IV-2. Forty-seven per cent of the eighth-grade boys in the three neighborhoods scored 6 or more, and one-fourth scored 8 or more. There were neighborhood differences, however. High (and it will be recalled that this neighborhood is also highest of the three in juvenile delinquency) stood out, with more than half scoring 6 or more and 28 per cent scoring 8 or more. In contrast, 42 and 38 per cent, respectively, in Low and Medium scored 6 or more, and less than one-fourth scored 8 or more. At the low ends of the distributions, there were fewer boys in High than in the other two neighborhoods who scored 3 or less. The disproportionate numbers of boys scoring 8 or more and 3 or less in High, however, came mainly from the adjustment classes,10 as may be seen from the lower portion of Table IV-2.

We have referred to the outlook represented by these items as one that is favorable to delinquency. We have not meant to imply that children who absorb such a philosophy will necessarily become delinquents or that those who do not will not. Delinquency in the legal sense has many causes, ranging from the thoughtless impulsiveness of the moment to profound personality disturbances and including youngsters who are simply carried along—whether innocently, by threat, by a process of what has been described as group intoxication, or by simple conformity —in the delinquent activities of others. Similarly, there are many constraints, ranging from the absence of opportunity through timidity to the influence of associates. What we meant was quite literally that such an outlook is one that could be expected to be favorable to delinquency; whether it materializes in action would have to depend on other f actors.11

It may be of some interest to examine the sixteen items in the light of what Albert Cohen has described as the delinquent subculture. Cohen describes the normative strands of this subculture as nonutilitarian (e.g., "There is no accounting in rational and utilitarian terms for the effort expended and the danger run in stealing things which are often discarded, destroyed or casually given away.") ; malicious (". . . an enjoyment in the discomfiture of others, a delight in the defiance of taboos itself"); negativistic ("The delinquent's conduct is right by the standards of his subculture because it is wrong by the norms of the larger culture"); concerned with the pleasures of the moment rather than with long-range goals; versatile in the variety of outlets for the expression of these attitudes; and intolerant of restraints except for those informal pressures emanating from the group itself.12 With the exception of versatility (and this possibly because we did not have the foresight to include a variety of such items in the questionnaire), all of these strands seem to be reflected in our sixteen items. One questionnaire item (F 33) that is missing from our set of sixteen items, perhaps because it does not include the qualification of conformity to the group, does express the value placed on freedom from restraint; but it is found in two of the four clusters from which the sixteen items were selected. The one major aspect of our items that is not explicitly included by Cohen in his description of the delinquent subculture but is not unrelated to Cohen's discussion of the dynamic roots of this subculture is the sense of pessimism, futility, and of the lack of real concern of human beings for one another's welfare.

Despite the evidence of the scores on the items to the effect that the outlook we have been discussing is most pervasive in the high-delinquency, high-drug-use, high-poverty, and otherwise highly deprived neighborhood and that it is quite pervasive in the other two relatively high-delinquency neighborhoods, it may be that we have been making too much of these sixteen items. We do not know, for instance, whether these items would also be linked in better-off sections of the city or, for that matter, whether the implied philosophy of life might not be a major current of the entirety of our civilization. Lacking this essential background, it could be a mistake to place much emphasis on what is implied by these items as something related to the causal context of the vulnerability of neighborhoods to the spread of drug use. Our major interest, therefore, is in the balance of the four clusters to which these sixteen items were common, and on the differentiations implied by the differences in the clusters.

THE LOW-DRUG-USE NEIGHBORHOOD

In the neighborhood with relatively low drug rates, the most striking features of the delinquency-orientation cluster are that the two items involving claims of personal contact with heroin use (G 48: "Saw someone take heroin" and G 49: "Know at least one user") are tied to the delinquent outlook and that this outlook is associated with correct answers and few "don't know" responses to information items. This sort of clustering is not found in the other neighborhoods. One may say that, in this neighborhood, the youngsters who tend to develop a philosophy of life favorable to delinquency are also those who tend to "know the score" with regard to narcotics. Specifically, we find the following items in the cluster:

G 16-30: Fewer than seven "don't knows" on fifteen information items

G 19: Most addicts did not start before they were thirteen

G 20, 28: Right on both legal items

G 22: Heroin costs more than one dollar a shot

G 26: Addicts are not permanently cured

G 27: It is not true that more girls than boys use heroin

Closely related to the two personal-contact items and also included in the cluster is Item G 47 ("Most information about drugs picked up on streets"). This item is, however, common to three of the four clusters we are discussing. The cluster also includes several attitude items related to drugs:

G 2: Should not tell authorities about user

G 6: Smoking marijuana is not the worst thing I can think of

G 7: Taking heroin is sometimes excusable

G 9: Users do not have fewer brains

G 11: Users are not more poorly dressed

In addition, there is an item that fits with the basic delinquent-philosophy cluster, one reflecting an attitude of social alienation, F 10 ("You are a fool to believe what most people tell you") . Finally, we find what, in the context of the rest of the cluster, we can regard only as "whistling in the dark," Item F 1 ("I'm a very lucky person") •13 Items G 2, G 6, G 7, and G 11 are also found in one of the two delinquency-orientation clusters in High, and Item G 9 in the corresponding cluster in Medium.

One may be inclined to assume a causal connection between direct personal contact with heroin use, on the one hand, and correct information and favorable attitudes toward narcotics, on the other. We must then ask, why did we not find a similar constellation in the other two neighborhoods?

Actually, we did find a similar cluster in Medium,14 but this cluster was not tied to the delinquency-orientation cluster, and it does not include the three drug-related items of that cluster, probably the most favorable to drug use in the questionnaire. We also find a cluster of contact and information items in High,15 but this is also not tied to the delinquency-orientation cluster, and it is virtually devoid of items favorable to drug use. The one exception is Item G 6, which denies that "just the idea of smoking marijuana is the worst thing I can think of"-an attitude which the authors of this volume share.

Thus, there seems to be ample ground for assuming that contact with drug use" is tied to relevant information. The question, however, is why contact and information are tied to favorable attitudes toward drug use and generally to a delinquent philosophy of life in Low-and not so in the other two neighborhoods. The answer seems to lie in the very issue of the extensiveness of drug use. It seems reasonable to assume that in Low the only individuals likely to be exposed are the delinquents and potential delinquents, i.e., those who share the delinquent philosophy. In the other neighborhoods, by contrast, exposure is sizi much more common and the availability of information so much greater that contact and information have no other significance.

It is consistent with this interpretation that considerably fewer of the boys in Low claim to know a heroin-user-17 per cent, as compared to 32 per cent in Medium and 45 per cent in High. Similarly, considerably fewer claim to have seen someone taking heroin-13 per cent, as compared to 24 and 39 per cent.

The picture with regard to accurate information is not so clear. Low is not consistently the neighborhood with the lowest percentage of correct answers. The issue is, however, confused by the fact that the subgroup with by far the lowest percentage of correct answers, and consistently so on almost every information item, consists of the boys in the adjustment classes in High. One may guess that these boys are generally poor learners, not merely at school. At any rate, the effect is that High does poorly, rather than that Low does relatively well on the information items.

We based a score on the six information items that clustered together in all three neighborhoods, not including the "don't know" index, but scoring G 20 and G 28 separately. Fifty-seven per cent of the boys failed to give correct responses to four or more of the six items. The corresponding figures for High and Low were 61 and 62 per cent, respectively; for Medium, it was 43 per cent.

These findings are not inconsistent with the hypothesis that the kind of information represented by these items goes with exposure. The cluster analyses were carried out separately for each neighborhood. This means that the relationship between exposure and correct information were studied by the neighborhoods' own standards of information. The level of accurate information in High seems to be quite low—mainly, as we have noted, because of the adjustment-class boys—but the relationship nevertheless appears. The level of accurate information in Low is equally low, and the relationship also appears. The level of accurate information is considerably higher in Medium, and the relationship again appears.

To summarize: Certain kinds of information go along with exposure to the use of narcotics. In Low, such exposure tends to be limited to the boys whose outlook on life is favorable to delinquency. Consequently, the exposure and information items are drawn into the delinquency-orientation cluster. Attitudes favorable to drug use may be interpreted as an expression of the delinquent philosophy of life.

THE MEDIUM-DRUG-USE NEIGHBORHOOD

In Medium, we found eleven items added to the common delinquency-orientation cluster. One rejected an additional middle-class standard of deportment (F 3: "Loudness around the house is OK"). One expressed self-confidence (F 15: "Nothing can stop me"); this may be regarded as an aggressive counterpart of the "I-am-a-lucky-person" item found in the Low constellation. Two are concerned with values—one (F 33) accepting the value of freedom to do what one wants and not be held back by other people, the other (F 34) rejecting the value of being of service to people regardless of credit.

Seven of the items are related to narcotics. One (G 23) involves misinformation to the effect that it is legal to give heroin or marijuana as long as one does not sell it. Three of the items involve rejection of arguments against taking heroin:

G 32: Hurting people close to you is not a main reason

G 36: Not having real friends is not a main reason

G 39: Becoming too different is not a main reason

Three of the items involve the image of the heroin-user:

G 9: Users do not have fewer brains

G 12: Users do not get fewer kicks out of life

G 13: Users do not have fewer close friends they can trust

If the general delinquent-philosophy cluster seems to express pessimism and futility, the boys in this neighborhood who share the outlook seem to be adding, "But I won't let it get me down." The orienting combination of ideas is explicitly antisocial and aggressively self-sufficient. One sees this trend in the non-drug-related items (F 15, F33, and F 34), as well as in the rejection of the particular reasons against drug use that are tied to the cluster.

TO be sure, G 36 may follow from G 13; if one perceives heroin-users as not having fewer close friends they can trust, then one cannot consistently accept the lack of real friends as a major reason for not taking heroin. We may note, however, that a high valuation on close friendship (Item F 27) is not included in the cluster and wonder why G 13 and G 36 should be salient enough to these boys to get into the cluster at all. We may note, further, that G 13 does not get into the delinquency-orientation clusters of the other neighborhoods, wonder why this neighborhood should differ in this respect, and note that G 36 gets into one of the high delinquency-orientation clusters without the support of G 13. We may note, finally, that another construction can be placed on the conjunction of the two items which is more consistent with the cluster as a whole: people in general do not have close friends they can trust; users can, therefore, be no worse off than anyone else, and the argument of loss of friends can hardly be taken seriously as a deterrent to anything. By this construction, the two items get into the cluster precisely because of the centrality of the issue that one must stand on his own and do whatever will get him what he wants. If this interpretation is correct, it seems reasonable to interpret all six of the drug-related items as an expression of this central outlook, rather than as an expression of favorableness toward drug use per se.

Of special interest is the remaining drug-related item in the cluster, G 23. This is the neighborhood that makes the best record on the information items. The appearance of one item of misinformation in the cluster—and on so important a point—comes, therefore, as a surprise. We have already noted, however, that, at best, such items can be said to measure information in only a limited sense—that of being sufficiently au courant for the correct alternative to seem the most reasonable—and that the responses may reflect attitudes rather than information per se, a situation that would be evidenced by a tie-in of an information item with attitude items. This is such an instance, and it seems likely that the item does reflect an attitude.

Consider the precise wording of the item: "It is against the law to sell heroin or marijuana, but they can't touch a person if he gives it away." Who are "they?" The police, the defenders of law and order, the representatives of the mores of the larger society, the out-group? The item as a whole suggests that there is a loophole in the law„, a breach in the defenses of the detested out-group, a way of beating them. To one who holds to an aggressively delinquent philosophy of life, the contemplation of such a breach may be so delightful as to make it difficult to resist; the wish, we suggest, is the father of the response. There are many loopholes in the law, and finding them must be an ideal expression of a delinquent philosophy, a violation of the spirit of the law with a minimum of risk, a malicious thumbing of one's nose at respectability with an assured get-away. Loopholes do exist; why not this one?

To summarize: The boys in the medium-drug-use neighborhood who share in the delinquent orientation do so with an emphasis on rugged individualism, on the principle that one must stand on his own and do whatever will get him what he wants, regardless of whom it may hurt. In its generic and its specific aspects, the delinquent philosophy carries with it certain attitudes favorable to drug use.

THE HIGH-DRUG-USE NEIGHBORHOOD

We have spoken of two delinquency-orientation clusters in the neighborhood with the highest drug rates. In addition to the sixteen items of the general delinquency-orientation cluster, the two clusters have five items in common—or a total of twenty-one of the thirty-six items involved. Moreover, ten of the fifteen items not common to the two clusters fall in one of them, so that the second cluster has only five of its twenty-six items unique to itself. This raises the question of why we bother to distinguish the second cluster at all. Or, alternatively, why not content ourselves with one twenty-one–item cluster, rejecting the other items as behaving in a statistically suspicious manner?

To explain the issue, we must refer to our procedures in discovering clusters. As is explained in Appendix E, we began by isolating what we call "prime clusters," adding additional items to identify what we have been referring to as clusters. For the distinction between prime clusters and the more inclusive clusters and for the rationale of the following statement, the reader is referred to Appendix E. For present purposes, it may be sufficient to assert that the essential character of a cluster is most clearly defined by scrutinizing the items in the prime cluster."

Each of the prime clusters in the two clusters we are discussing consists of six items," five of them members of the general delinquency-orientation cluster. The complete cluster developed around each of the prime clusters, of course, includes the remaining items of the general delinquency-orientation cluster.

The items of the first prime cluster are:

,F 4: Not much chance for a better world F 6: Police open to bribes

F 22: Most people better off not born

F 24: Parents always looking to nag

F 25: Everybody really out for himself; nobody cares

F 18: Live for today rather than try to plan for tomorrow

The last item is not in the general delinquency-orientation cluster, nor is it in the second cluster.

The items of the second prime cluster are:

F 9: Shouldn't always treat girls nice

F 7, 13, 26: Reject middle-class rules of deportment

F 17: Police pick on people

F 19: Police practice racial discrimination

F 23: Police favor their friends

F 10: Fool to believe what most people try to tell you

Again, the last item in the list is not in the delinquency-orientation cluster; it is, however, a member of the first cluster. This item also happens to be the weakest member of the second prime cluster.'

It is clear that the first prime cluster has picked up all of the items of the general delinquency-orientation cluster emphasizing the mood of pessimism, social isolation, and futility and, so to speak, underscored the selection by adding another emphasizing the undependability of the future. The second prime cluster, on the other hand, has picked up the items reflecting negative attitudes toward the representatives of social authority and the rejection of accepted standards of deportment in middle-class society. The police item in the first speaks of the corruption and selfishness of human beings; the police items in the second and perhaps the last item, too, speak of their meanness. The first prime cluster spells hopelessness; the second, negativism.

Even so, we might not be inclined to make much of these differences were it not for additional differences in the augmented clusters and for the bearing on attitudes toward narcotics.

We have already mentioned that there are ten items in the first cluster which are absent from the other. One of these, already mentioned, is in the prime cluster. The other nine are all concerned with the arguments against using heroin. These are:

G 31-41: Accepts less than nine of the eleven arguments18

G 31: Becoming a slave to heroin not a main reason

G 33: Having to continue even when kick wears off not a main reason

G 34: Becoming a helpless tool of pushers not a main reason

G 36: Not having real friends not a main reason

G 37: Losing chances of steady income not a main reason

G 38: Never being safe from the police not a main reason

G 39: Becoming too different not a main reason

G 40: Losing ability to work well and be good at sports not a main reason

Another argument (G 32: "Hurting people close to you not a main reason") also appears in this cluster, but it also appears in the second cluster. The only argument items not appearing in the cluster are G 35 ("People will look down on you") and one that was not included in the cluster analysis) This does not mean that the latter are accepted, but merely that their acceptance or rejection does not tend to hang together with the other items in the cluster.

By contrast, the five items appearing in the second cluster but not in the first are:

F 3: Loudness around the house is OK

F 33: Values freedom from restraint

F 6: Smoking marijuana is not worst thing I can think of

G 7: Taking heroin is sometimes excusable

G 11: Heroin-users are not more poorly dressed

The first two of the latter five items carry on the theme of the prime cluster, and the three drug-related attitudes are simply consistent with the general outlook expressed. That is, as in the delinquency-orientation clusters in the other two neighborhoods, we have no indication of anything here that would move youngsters toward narcotics other than the convention-challenging aspect of the delinquency orientation itself.

In the case of the first cluster, however, we do seem to have something quite different. The connection between the delinquency-orientation complex and attitudes favorable to experimentation with drugs cannot be interpreted simply in terms of reckless bravado in the face of a, hostile world. Here, we come much closer to an attitude of surrender, a mood of "What difference does it make anyhow?" When one is in this mood, hardly any argument against heroin use is convincing, and most tend to be rejected outright. The point of greatest danger seems to be right here. When one is in a mood of defiance of convention, the sheer act of taking the drug may give some measure of gratification, but not inherently more so than other convention-defying activities; the psychopharmacological effects of the drug are irrelevant. When one is in a mood of hopelessness and futility, however, the psychopharmacological effects of the drug are directly relevant; they provide a chemical balm to a sorely depressed spirit. It is not surprising, therefore, that the prodrug items of the general delinquency-orientation cluster are more closely linked to the first cluster than to the second.

Thus, Item G 1 ("Drug use is a private affair") has an average profile correlation of .44 with the items of the first prime cluster, as compared to one of .40 with the items of the second, and an average tetrachoric of .17, as compared to .14. Items G 3, 4, 5 (agreeing with at least one: "Heroin not so harmful as people say"; "Taking a little heroin once in a while doesn't hurt"; "Smoking marijuana at parties OK) has an average profile correlation with the first prime cluster of .67, as compared to .58 with the second; and an average tetrachoric of .31 with the first, as compared to one of .21 with the second. Item G 8 ("Using heroin is OK if you make sure you don't get hooked") has corresponding profile correlations of .54, as against .42, and tetrachorics of .18, as against .07.

To complete the record on the two clusters we have been discussing, the three items that have not yet been mentioned which are not in the general delinquency-orientation cluster but which are common to the two clustersle are:

F 5: I can get away with things

G 2: Shouldn't tell authorities about user

G 47: Information about drugs from streets

The only noteworthy point about these items is the contrast between F 5 and the "I'm a very lucky person" of the low-drug-use neighborhood delinquency-orientation cluster and the "Nothing can stop me" of the medium-drug-use neighborhood cluster. Like its counterparts in the other two neighborhoods, F 5 rings the one optimistic note of the two delinquency-orientation clusters; but, unlike its other-neighborhood counterparts, F 5 is focused much more on the illicit.

Before closing this review of the delinquency-orientation clusters in the high-drug-use neighborhood, we must note still a third cluster that is related to the first two.k

The third cluster includes thirty-nine items, thirty of which are found in the first or second clusters. It includes twelve of the sixteen items of the general delinquency-orientation cluster. Except for the four items missing from the latter group, it includes all of the first cluster and, with one additional exception, all of the second cluster. Two of the missing items from the general delinquency-orientation cluster are in the first and second prime clusters—one in each, of course. These items are, from the first prime cluster, F 22 ("Most people better off not born") and, from the second prime cluster, F 9 ("Shouldn't always treat girls nice"). The other two missing items are the compound item F 2, 16, 21 ("Unfavorable to parents") and F 29 ("Values power"). The fifth item present in the second cluster but not in the third is one of the second-prime-cluster items, F 10 ("Fool to believe what most people try to tell you").

There are six items in the third prime cluster, all drug-related. These items are:

G 3, 4, 5: Agree with at least one of following: Heroin not so harmful as people say; taking a little heroin once in a while doesn't hurt; smoking marijuana at parties is OK

G 6: Smoking marijuana is not the worst thing I can think of

G 7: Taking heroin is sometimes excusable

G 8: Heroin OK if you don't get hooked

G 11: Users not more poorly dressed

G 47: Information from streets

The nine items in the cluster which are not present in either the first or the second are:

G 9: Users don't have fewer brains

G 12: Users don't have fewer kicks out of life

G 13: Users don't have fewer friends

G 16-30: "Don't know" to fewer than seven of fifteen information items

G 26: Addicts not permanently cured

• 29: Marijuana less costly than heroin

G 48: Saw someone taking heroin

G 49: Knows one or more heroin-users

This cluster, then, is centered on narcotics. It draws in many of the items of the delinquent philosophy of life, both in its general form and in its specific varieties, but some of the themes characteristic of this philosophy are muted. One may say that there is a lack of full conviction about the delinquent outlook. What seems to have happened is that the drug-using subculture has been absorbed and, along with it, aspects of the associated delinquent outlook. Attitudes toward narcotics do not flow from the delinquent orientation; the philosophy of delinquency is rather a by-product of the absorption of attitudes toward narcotics.

As might be expected from the nature of the cluster, the items in the general delinquency cluster that involve drugs are more closely related to the third than to the first two prime clusters, the rejection of arguments more closely related to the third than to the first, the narcotics-related items of the second cluster more closely related to the third than to the second prime cluster.' In brief, at every point where a comparison can be made, the drug-involved items are more closely related to the third prime cluster than to the first or second.

To summarize: In the neighborhood with the highest drug rates and also with the highest delinquency rates, we have found two strands in the delinquent orientation—one giving emphasis to the negativistic aspects, one to the sense of futility. Both draw in attitudes that are favorable to the use of narcotics, but the second in a more dangerous form; not only is the second associated with the rejection of reasons that might serve as deterrents, but its basic mood is one that can be relieved by the psychopharmacological effects of narcotics. In addition, we have found evidence of a third strand of the neighborhood culture, one that absorbs the drug-using subculture and much of the delinquency orientation that goes with it. The three strands are interwoven.

STATISTICAL FOOTNOTES

a An explanation of tetrachoric correlation is given in Appendix C. along with a general explanation of the meaning of correlation coefficients. Briefly, the tetrachoric correlation is computed from dichotomous (two-valued) variables and provides an estimate of what the correlation would be if it were computed from corresponding many-valued variables, the distributions of which have been normalized.

b The formula for computing tetrachoric correlations is very involved, so we used an approximation procedure which is sufficiently accurate for most purposes if the dichotomies do not break more extremely than 80-20; for more extreme breaks, the procedure becomes increasingly inaccurate. In some instances, we formed compound items. In some instances, however, there were no other items with which such items could be sensibly combined. One such item (see Note j) was G 41 (i.e., Item 41 in the Form-G questionnaire; the questionnaires are reprinted in full in Appendix D), which dealt with one reason for not taking heroin. A number of other items were also omitted from the cluster analysis on the same grounds. Three were concerned with the image of the heroin-user: G 10 ("Nonusers more fun to be with"), with percentages of 83, 91, and 92 in Low, Medium, and High, respectively; G 14 ("Nonusers get along better on their own"), with percentages of 80, 92, and 83; and G 15 ("Nonusers better able to take care of themselves"), with percentages of 84, 95, and 86. One was concerned with exposure to heroin: G 50 ("Had a chance to take heroin"), with percentages of 6, 10, and 10. In addition, there were F 20 ("Sometimes think people like me hardly good for anything"), with percentages of 17, 21, and 23; and F 35 ("Value job one can count on and knowing one can always get along"), with percentages of 89, 92, and 93.

c Strictly speaking, the idea of statistical significance is not relevant. When computing correlations in a random sample of cases from a larger population, the sample may differ from the population, and the correlations may, as a consequence, differ from the correlations that would have been obtained if the entire population had been utilized. Because of certain mathematical relationships involved, it is possible to estimate the range within which the "true" correlation probably lies with any specified odds_generally taken as 19 to 1. If this range does not include zero, the correlation is said to be "significantly greater than zero," or simply "significant." In the present instance, however, we are dealing with virtually total (i.e., total except for absentees) specified populations at a specified time, not random samples of much larger populations. It is sometimes convenient, however, to provide a crude guide to how large a correlation to take seriously by pretending that the population studied is a random sample of a fictitious, much larger population and applying the test of statistical significance to the obtained correlation. It is in this sense that we speak of statistical significance above. Although tests of the statistical significance of correlation only take into direct account the possibilities of sampling errors, they take indirectly into account random measurement errors (e.g., accidental misreading or misinterpretation of items because of a momentary set or accidental markings of unintended answers) as well. This follows from the fact noted elsewhere that, the greater the measurement errors, the more difficult it is to obtain statistically significant correlations.

d The smaller the role that chance plays in determining responses to an item (whether the chance factors are related to ambiguities of wording—it being a matter of chance which meaning the respondent happens to seize upon on a particular occasion—or whether the chance factors enter in a variety of other ways), the more reliable the item is said to be. The measurement of reliability hinges on the fact that substantial correlations are not likely by pure chance. In the present instance, we speak of minimum estimates because we have not met the optimal conditions for measuring item reliabilities. A final point to be made in the matter of item reliabilities is that the correlations of correlational profiles described in the following paragraph are remarkably high. To those familiar with psychometric theory, it will be clear that item communalities must also be very high, and it will be recalled that communalities also provide minimum bound estimates of reliability.

e The cluster analyses described below.

f See Appendix E for the rationale of this procedure. In the preceding chapter, we referred to the pattern of correlations involving a variable in a reversed application. There we argued that the percentage of the population living at a new address cannot have the same meaning in the three boroughs. The patterns of correlations between this and the other variables were too radically different from borough to borough for the variable to be measuring the same thing. Here we are asserting that different variables with similar correlational patterns probably have related meanings.

g Three of these are actually compound items, each, as it happens, being composed of three items. Thus, for the purpose of computing tetrachoric correlations, items 2, 16, and 21 of the first part of the questionnaire were combined into a single item. This item was scored 1 if the respondent gave an answer unfavorable to parents on one or more of the three component items; it was scored zero if the respondent answered favorably to parents on all three items. Similarly, three items involving issues of what we have labeled middle-class manners—items 7, 13, and 16 of the first part of the questionnaire—are scored in the same way for rejection of middle-class rules of deportment.

Finally, items 3, 4, and 5 of the second part of the questionnaire were combined and scored in the same way for favorableness to drugs. These combinations were made in order to avoid extreme marginal breaks. See Note b, supra.

The average of the profile correlations of the sixteen items with one another was .56 in both Low and High, and it was .60 in Medium. The average tetrachoric correlation was also the same in Low and High, .23, and in Medium it was .26.

h The average profile correlation of the items in the first prime cluster with one another is .67, and the average of the tetrachoric correlations of these items with one another is .29. The corresponding averages for the second cluster are .71 and .32. The average profile correlation of the items in the first with the items in the second is .54, and the average of the tetrachoric correlations of the items in the first with those of the second is .18. Each of these prime clusters is more closely related to the other, by the test either of the average-profile correlation or the average tetrachoric correlation, than it is to any other cluster.

i Its average profile correlation with the other items in the prime cluster is .63; the item with the next lowest average profile correlation is F 17, with an average of .70. Its average tetrachoric correlation with the other items in the prime cluster is .24; the item with the next lowest average tetrachoric correlation is F 19, with an average of .31. Without this item, the average profile correlation of the remaining items with one another is .73, and the average tetrachoric is .34.

The item is G 41 ("Health will be ruined and life will be full of worries and troubles"); the percentages of agreement that this is one of the main reasons for not taking heroin are 87 in Low, 88 in Medium, and 91 in High.

k The average profile correlation of the items in the first prime cluster with those in the third is .46, and the average tetrachoric is .12. The corresponding figures for the second and third are .48 and .14. The average profile correlation of the items in the third prime cluster with one another is .71, and the average tetrachoric is .30.

l The statistics on the three items in the general delinquency cluster are, giving in each case the average profile correlation first and then the average tetrachoric correlation with the items of the third prime cluster: G 1—.52, .53; G 3, 4, 5—.74, .36; G 8—.72, .38. These may be compared to the figures already cited for the first and second clusters. On the arguments, the third cluster draws in item G 35, with statistics of .60, .13; for the arguments in the first cluster, the comparisons, giving the statistics for the correlations with the third prime cluster first, are: G 31-41—.63, .18 versus .47, .07; G 31—.48, .10 versus .47, .10; G 32—.65, .12 versus .57, .11; G 33—.50, .04 versus .40, .00; G 34— .54, .12 versus .43, .10; G 36—.68, .21 versus .49, .09; G 37—.58, .12 versus .49, .06; G 38—.65, .19 versus .43, .01; G 39—.60, .14 versus .45, .04; G 40—.65, .22 versus .47, .07. On the drug-involved items of the second cluster: G 2—.56, .21 versus .49, .16; G 6—.72, .28 versus .53, .19; G 7—.69, .30 versus .54, .17; G 11— .68, .24 versus .41, .09; G 47—.68, .26 versus .41, .09.

1 To avoid redundancy, we shall refer to these neighborhoods as "High," "Medium," and "Low," respectively.

2 There were 442 boys in High, 212 in Medium, and 271 in Low, respectively. The data are given in Table IV-1. There are also a number of Jewish day schools (the Jewish equivalent of the parochial school) in Low. These were not included in the study for practical reasons (e.g., the absence of any central administration with which to deal) and on theoretical grounds: relatively few Jewish boys nowadays become involved in delinquency and even fewer with narcotics, and the ones who attend the day schools in this area are particularly likely to be isolated from the surrounding neighborhood culture. These schools are, by their very nature, segregated—not only from Gentiles (and this, of course, includes Negroes and Puerto Ricans), but also from Jews of less religiously Orthodox background, who are more likely to mingle freely with other elements of the community. The children spend many more hours in school and, hence, are less free, even if so inclined, to participate in the street culture. Even more fundamentally, from our point of view, many come from other parts of the city and, in some instances, from outside the city; they cannot, therefore, be said to be representatives of some facet of the neighborhood culture. The Jewish boys in the neighborhood public schools were included in the sample, both because there was no way of excluding them and because they were in much closer contact with the neighborhood culture than were those attending the day schools. They probably constitute a substantial proportion of the boys in Low, but very negligible proportions of the boys in the other two neighborhoods.

3 Accodring to New York City Youth Board statistics, Medium is on a par with High, whereas, according to our own data (collected from other sources and with other criteria; for instance, as was indicated in the preceding chapter, to separate as far as possible the drug-use variable from other types of delinquency, we did not include drug violations in the delinquency counts, and we did not include certain behavior disturbances which to our minds do not represent delinquencies but which were included in the Youth Board figures because they were called to the attention of the Juvenile Aid Bureau of the Police Department for one reason or another), it is on a par with Low.

4 L. Srole, "Social Integration and Certain Corollaries: An Exploratory Study," American Sociological Review, 21, (December 1956) 709-716.

5 The two parts of the questionnaire, labeled respectively "Form F" and "Form G," are given in Appendix D. The background questions were intended mainly to make it possible to put together the two parts answered by a given individual. Since the questionnaires were separated by classes, the birthday proved sufficient for this purpose. When the second part was being collected, one of the boys suddenly realized that he could be identified by his birthday and tore his paper up. We wanted the ethnic identifications of the boys, but could not ask this directly. We instead gave each teacher a list of the birthdays of the children; from this, she could identify the children and give us the desired information, but she never saw the filled-out questionnaires. On the other hand, we never saw the names of the children. As soon as the two parts were collated and the ethnic information added, the papers were sorted into eleven subgroups, as described below. Within these subgroups, the particular class that a given questionnaire was in could no longer be determined. In this way, the pledge of anonymity was fulfilled.

6 In High public school, there were, in addition to the regular classes, what were designated "adjustment classes." These classes contained boys who were not mentally retarded but who presented educational and/or behavior problems.

7 These figures will be evaluated below for their accuracy.

8 It should be said, however, that the questions were carefully reviewed, both as to wording and format, by a committee of teachers in the school with the most serious reading problems. This invaluable help is gratefully acknowledged. In addition, the questions were pretested in face-to-face interviews with boys in a somewhat comparable neighborhood, and question wordings were revised as sources of ambiguity became apparent. The interviews were explicitly aimed at the meaning of the items rather than at getting answers. Special words like "heroin" and "marijuana" were explained in the course of the administration, and colloquial synonyms were written on the blackboard. It has already been noted that the questionnaires were administered item by item, the teachers pausing after each item to make sure that everyone understood. In the parochial schools, members of the research staff substituted for the teachers. In brief, every measure that we could think of was taken to make sure that our end of the communication process was as clear as it could be under the circumstances.

9 Experts will, of course, be confronted by difficulties stemming from ambiguities in "take the cure" and "never go back on drugs again." These ambiguities may be assumed to be too subtle to bother our respondents.

10 As explained in an earlier note, these are special classes for children with reading problems and/or other behavior problems; they do not include children classified as mentally retarded. It is, perhaps, noteworthy that almost one-fourth of the boys in High are assigned to such classes. There are no comparable classes in the other two neighborhoods.

11 Even so, there is some evidence that children who share this philosophy are more likely than others to get into trouble. The high scores of the boys in the adjustment classes are, of course, germane. In a doctoral thesis in the Sociology Department at New York University, Janet Leckie reports the results of administering fourteen of the twenty-two items we have been discussing (counting the components of the compound items as separate items) to 292 girls in a vocational high school in New York City. The drug items and the two value items were not included. Forty of the girls were classified as "troublemakers" by school authorities, and twenty as "outstanding" children. Three-fifths of the "trouble-makers" were in the high-scoring third of the children as compared to 15 per cent of the "outstanding" girls; and about one-fifth of the "trouble-makers" were in the low-scoring third, as compared to more than half the "outstanding" girls. More than half the "trouble-makers" scored 6 or more on the fourteen items, as compared to only one of the "outstanding" girls. Considering that the population on which Miss Leckie tried these items out is so different from the population in which they were selected (older and female as compared to younger and male), this indication that the items measure something that is likely to be reflected in behavior seems remarkable. We had interpreted the set of items as yielding an index of "delinquency orientation" before we asked Miss Leckie to include it in her battery of measures.

12 A. Cohen, Delinquent Boys (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1955), pp. 26-28.

13 Interestingly enough, apart from considerations of clustering, this item received the highest proportion of assent in the most deprived of the three neighborhoods. About 74 per cent of the Negro boys (both in the regular and in the adjustment classes) agreed with this item, and the over-all percentage of agreement in High was 70. In Low, about 58 per cent of the boys agreed with the item.

14 This cluster includes items G 6, G 7, G 11, G 16-30, G 19, G 20, G 28, G 22, G 26, G 27, G 47, G 48, and G 49. In addition, it includes two more information items, G 16 ("Heroin not from same plant as marijuana") and G 29 ("Marijuana costs less than heroin"). The rest of this cluster consists of F 17 ("Police practice racial discrimination"), F 30 ("Values being popular and respected"), and F 31 ("Values ease and comfort"). Still another distinguishable cluster consists of the same drug-related items, except for G 7 and G 11, and three more information items, G 18, G 23, and G 30; there are no other items in this cluster.

15 This cluster consists of items G 6, G 16, G 16-30, G 18, G 19, G 20, G 28, G 21, G 22, G 23, G 27, G 29, G 47, G 48, and G 49.

16 The very fact that items G 48 and G 49 cohere with information suggests that the answers to these items are apt to have at least some truth. We shall, however, return to the issue of how seriously to take the answers to items G 48 and G 49 in Appendix H.

17 We have not referred to the prime clusters in the preceding presentation because they did not seem to tell any different story than was obtainable in greater detail from a consideration of the more inclusive clusters. In the present instance, the consideration of the prime clusters does make a difference.

18 Approximately half (47 per cent) of the boys in the three neighborhoods combined accepted nine or more of the arguments as "one of the main reasons that would keep you from taking heroin."

19 The two other such items are F 10 and G 32.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|