5 The Individual Environment

| Books - Narcotics Delinquency & Social Policy |

Drug Abuse

V The Individual Environment

Thus far, we have considered only the differentiating characteristics of regions within which drug use thrives. In these very environments, however, there are individuals who succumb and others who do not. We turn now to the question of whether we can find differences in the specific environmental backgrounds of these two classes that might help to explain why some do and some do not.

Our first look at the personal environment of the user-to-be is at certain gross characteristics of his personal history, his family, and his peer associations and is, by design, panoramic. A more sharply focused, minute investigation of the family background of individuals who become addicted as these backgrounds relate to their personalities and psychopathologies will be found in chapters X and XI. At the moment, we wish to explore the possibility that the personal experiences of the users included some obvious major deprivations that were either unique for them as a group or which they shared wth the nonusing delinquents but not with those youths in the same neighborhoods who became neither users nor otherwise delinquent.

The study which was designed to explore these questions compared the personal backgrounds of four groups of boys in the age range from sixteen through twenty (the median age was nineteen) from neighborhoods similar in delinquency and drug rates. The study dealt with fifty-nine institutionalized drug-users who were not otherwise delinquent before they started to use drugs (we shall refer to them as "non-delinquent users"); forty-one institutionalized users who were otherwise delinquent prior to onset of drug use (to be referred to as "delinquent users"); fifty institutionalized delinquents who were not heroin-users ("delinquent nonusers"); and fifty-two controls ("non-delinquent nonusers") from the same types of neighborhood.

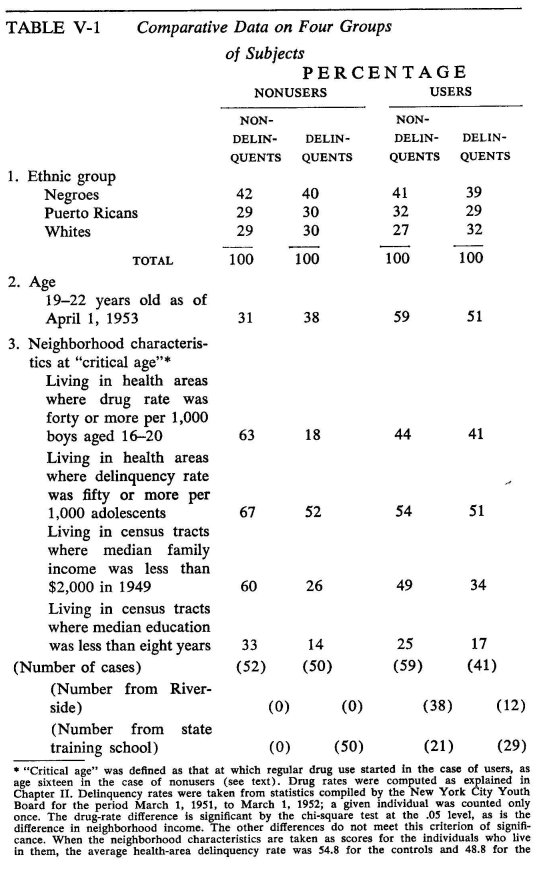

These four groups of boys were not selected with an eye to any characteristics other than those specified above, except that we tried to get, for each group, equal proportions of white, Negro, and Puerto Rican boys who came from health areas that are comparable with respect to the incidence of drug use and who were of the same age levels. a Some comparative data on the four groups are given in Table V-1.

In the original design, we had planned to take fifty cases from Riverside Hospital, naïvely assuming that these would all have been nondelinquents prior to their involvement with drugs; fifty cases of users from the New York State Vocational Institution at West Coxsackie, N. Y., again naïvely assuming that these would all have had histories of delinquency; fifty cases of nonusers from the training school at West Coxsackie, again (although this time excusably so) naïvely assuming that users who have undergone arrest, trial, processing at a reception center, and final allocation to the institution where we contacted them would have been detected as such before we picked them; and fifty control cases with no history of either drug use or any other kind of delinquency.

As might be expected from our use of the term "naïvely" and as is evident from Table 1, these plans went astray. The departures from our expectations were, however, instructive.

We first interviewed the boys of the three deviant groups in 1953— 1954. The control group was interviewed in the following year. We picked the boys in the control group by the following procedure: We first selected five junior high schools, one of them a parochial school, in areas of relatively high drug use. We then picked the graduating classes that, so we thought, would place the graduates in the age range characteristic of our first three groups. From the lists of the graduates, we then selected a large random sample of boys. We checked with the school authorities for any history of having been seriously suspected of chronic antisocial behavior (e.g., fighting, truancy), drug use, or other forms of delinquency, eliminating the boys with any such history. The remaining individuals were cleared through the Social Service Exchange to determine whether they or their families were known to any of the social agencies in the city. If they were, we checked with these agencies for any history of the boys' having been suspected of behavior that would disqualify them from the control group. We also checked with the Juvenile Court. In some instances, the social agencies to which the families were known refused to cooperate and, in such cases, the boys were automatically disqualified."

Letters were sent to all the boys whose names were cleared before we had completed the intended number of interviews. The letters explained that we were studying the experiences of boys in neighborhoods where many of the boys get into trouble with the law; that we had found out that the recipient had never been in such trouble (ever( so, we received a number of phone calls from anxious parents); that we would like to talk to him; and that we would give him $5 for his time.e Eventually, ninety of the 425 boys answered the letter. Of these, twenty-six did not keep their appointments. Of the remainder who were interviewed, five were eliminated because the interviews gave rise to suspicions of delinquency or drug use (one of these, for stealing $5 from the interviewer) and seven because they were clearly under age. This left us with the fifty-two control cases.

It is quite clear that we had grossly underestimated the degree of educational retardation among the delinquents and drug-users. The differences in age between the controls and the other groups would be even more marked if we had included the seven cases eliminated because of age.

It is also evident from Table V-1 that a history of delinquency prior to drug use is not nearly so determinative as we had supposed of whether a case will be found at Riverside Hospital or in a state reform school, although the difference ran in the expected direction. More than a fourth of our final sample of delinquent users turned up at Riverside, and over 35 per cent of the final sample of users without previous delinquency turned up at the training school. At any rate, this—to us unexpected—situation accounts for the facts that our sample of delinquent users was smaller than we had planned and that the sample of nondelinquent users was larger. A second sample of fifty Riverside cases, taken a year later and about which more will be said below, was more in line with our initial expectations, including only three with histories of prior delinquency.d

Not evident in the table is the fact that four of the first fifty interviewed subjects who were designated as nonusers at the training school asserted that they had been using heroin regularly prior to their incarceration and provided enough circumstantial detail for us to believe them. They were assimilated to our samples of users. Note, incidentally, that, if marked withdrawal symptoms are a criterion of addiction, these boys could not have been addicts; but they were regular users, nonetheless.1

The most striking feature of the table is the large difference between the delinquent and nondelinquent nonusers in the percentage of subjects coming from areas of very high drug use. Since we were trying to fill the sample with cases coming from such areas, the very low percentage of such cases in the delinquent nonuser group strongly suggests that, at least at the time of the study, delinquents from such areas were extremely likely to be users. It is, of course, possible that delinquent nonusers from high-use areas were being sent to another institution; but this conjecture is inconsistent with what we know of assignment policies, and we find it impossible to imagine an assignment policy which might result as an incidental consequence in the kind of pattern we found, delinquent and nondelinquent users and nondelinquent nonusers all being found in ample supply.

On the other hand, in taking our controls from predesignated schools in high-use areas, we have obviously unduly restricted this sample to boys coming from such areas. One can draw no inference from the plenitude of such cases, since, even in the areas of the highest drug and delinquency rates, the majority of boys have no known history of delinquency or drug use. The restriction does imply that the typical control case labored under a greater neighborhood-environmental handicap than did the typical cases in the other three groups.

We do not know, however, to what extent the control cases may have been atypical of the nondelinquent nonusing boys of the same neighborhoods. To a considerable extent, they were self-selected. They were the boys who were sufficiently attracted by the lure of $5 and/or the nature of the study to return the post card indicating their willingness to participate; they had to have enough self-assurance and willingness to talk about themselves not to be frightened off by the prospect of being interviewed; they had to be willing to earn their reward by giving up the time needed to get to our offices as well as that required by the interview itself; they had to be willing to engage in an individual enterprise that necessitated leaving their familiar haunts to report fqr the interview; they had to be sufficiently impressed by the university letterhead and/or not be sufficiently repelled by the prospect of talking to "professors"; they had to trust that they would actually get the promised reward; and they had to have enough responsibility to keep their appointments. It would not be in the least surprising if they were, indeed, an atypical group of boys.

The interviews lasted from one and one-half to two and one-half hours. The current status of the institutionalized respondents and their relative inaccessibility made it impractical to attempt more extensive investigation. The time restrictions compelled us to limit the scope of the interview. There was also another compelling reason for such a limitation—we were concerned with past events and situations and necessarily had to rely on recall. It may be taken as axiomatic that, even though we were to credit the respondents with the utmost candor, the further into the past that one seeks to probe, the less reliable is recall as an indicator of historical fact. We therefore limited ourselves to the relatively recent past: "the time just before [you] started using heroin regularly" in the case of the users and the age of sixteen (which we expected and, in fact, found2 to be the median age at which the users shifted from occasional to regular use) in the case of the nonusers.

The interviews were conducted in a relatively free style from the point of view of the order and exact wording of the questions. The interviewers, however, had before them detailed schedules of questions which they filled out as the interviews proceeded. All the interviewers were highly skilled in intensive interviewing. Most were advanced graduate psychology students or social workers, but the group included several Ph.D.'s in psychology and one in anthropology.

The interviews were designed to explore the nature and extent of drug use, relevant experiences, the home and family situation, education, friendships and leisure-time activities, orientation to the present and the future, attitudes toward drugs, and related matters.

In the cases of the drug-users and delinquents, it was possible to check many of the answers against available records, discussion with case workers or parole officers, and, in all of the Riverside and some of the training school cases, against the results of interviews with a parent. Data from all these sources were entered in the interview schedules. We computed a "reliability score" for each boy in terms of items of objective information that could be checked. A small number of interviews were rejected for an apparent lack of truthfulness or marked inaccuracy on the part of the boy; these cases were, of course, not included in this report. For the remaining cases, in instances of apparent contradiction by other information, we first checked each source for internal consistency on the point at issue and resolved the contradiction in accordance with predetermined principles for assessing credibility on particular points. On the whole, however, we had no reason to question the impression of the interviewers that the boys were sincerely cooperative and trying to report as accurately as they could. When the boys themselves were asked how they felt "about all this questioning," only 5 per cent gave negative reactions, as against 46 per cent who gave decidedly positive responses; the rest gave mixed reactions or something that could not be classified as favorable or unfavorable.

One other point is relevant with respect to the group comparisons reported below. We have already mentioned that the interviews were, in the main, focused on the time immediately preceding the "critical age" and that this age was defined somewhat differently for users and nonusers. For the users, it was defined as the age when regular drug use began, and, as it turned out, this varied from age thirteen to eighteen. For the nonusers, the "critical age" was arbitrarily set at sixteen (questions were put in terms of the time "just before you were sixteen"), and this was, of course, uniform for all nonusers. The answers of users and nonusers to such questions are, hence, not strictly comparable, since the time reference is not exactly the same.

By the time we interviewed the control group, we had thought of a number of areas that we wanted to explore which were not covered in the original interviews. About thirty new questions were added to the interview schedule, dealing with the boys' reference groups, the constructive activities in which they engaged, and a variety of matters relevant to the transition from adolescence to maturity. In order to provide some comparison data on these questions, we took a second sample of fifty Riverside cases. The interviews with this second set of cases were much briefer than those of the preceding year, dealing in the main with the new questions, although some of the original questions were retained.

We have already mentioned one difference between the first and second Riverside samples, namely, that the second included only three subjects with histories of delinquency before they turned to drugs; for all practical purposes, this group may be regarded as nondelinquent users. Apart from this, the only other statistically significant difference between the two Riverside samples, on items for which we had comparative data, was that somewhat more of the second sample answered a question about things they wanted but could not get in their critical year with some reference to a different way of life (e.g., getting out of the neighborhood). Such differences as were found are consistent with the description of the second sample as essentially one of non-delinquent users.3

Some Socializing Influences

Both drug use and juvenile delinquency are socially deviant forms of behavior. Their very existence indicates that the standards which society seeks to impose on all have failed to take sufficient hold.

Since the family is the primary agency for the transmission of standards of behavior, we shall compare the four groups of boys in terms of some aspects of their family backgrounds.

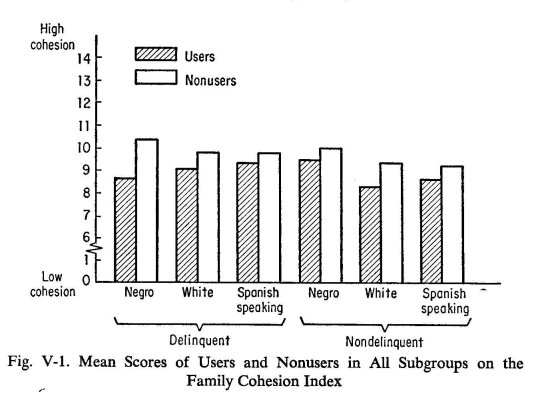

We constructed an index of the cohesiveness of the families with which the boys lived longest from their tenth to the critical year. The index was based on the answers to seven questions concerning quarrels among family members and various family practices and customs with respect to the celebration of holidays and birthdays, mealtimes, joint activities, and behavior when someone in the family was ill. Each answer was given a value of zero, 1, or 2—the higher value indicating a more frequent or more marked cohesive practice. For instance, if the family usually had dinner together, the family was credited with two points; if the boy said that the family had dinner together several times a week, the family was credited with one point; and if having dinner together was a rare occurence, the family did not get any points. By adding the total number of points on the seven questions, we got a score for each of our respondents that could serve as a rough indicator of the degree to which the members of his family stuck together.4

We assume that, the more cohesive the family, the more effectively it can function in transmitting the basic values of society to the developing child. It is, no doubt, possible that the values which a particular family transmits may themselves be deviant, and, from the point of view of the conservation of the social order, one may be inclined to wish that the families were less effective in such instances. Whatever standards of behavior the family may sponsor, a cohesive family (in the sense implied by our index) gives a child his first taste of the virtues of social discipline, a feeling of the need for human beings to accommodate themselves to one another, a sense of mutuality and "togetherness." This kind of feeling is, to our minds, the most basic of social values. It is that in terms of which the acceptance of social

standards as one's own is a consistent elaboration on one's experience.

There are other grounds on which one may internalize social standards, the most noteworthy being fear; but, in this case, the internalized standards remain essentially ego-alien and a source of frustration, and the self-imposed compliance makes it likely that reactions to frustration will be turned against oneself.5

We are not asserting that a child who is deprived of the experience of a cohesive family cannot acquire a sense of mutuality in other ways; we think it less likely that he will. Nor are we asserting that the years from ten to sixteen or thereabouts are the most critical years for such development; actually, there is reason to believe that the foundations are laid much earlier. In going back as far as the tenth year, however, we felt that we were already stretching the reliability of our informants to its utmost limits, and we were willing to assume that what happened in these later years would probably be indicative of what had gone on earlier or that, at the very least, the later experience would reinforce' or to some extent negate the effects of the earlier.

Nor are we asserting that family togetherness is necessarily a virtue. We take it for granted, for instance, that excess can transform any virtue into a vice. A harsh discipline that holds the members of a family to common activity against the will of its members can be intensely frustrating and teach lessons that are quite contrary to those we attribute to a cohesive family. We do not think it likely, however, that such a family could earn a high score on our index. We would expect, for instance, that the physical togetherness would be marred by constant bickering, that the family would break up as quickly as the formalities are over, and so on. Moreover, we would expect the interviews to have picked up evidence of the ritualistic, enforced character of such togetherness, and, if they seemed important enough, we would have modified our index accordingly.

At any rate, it should be borne in mind that the comparisons we are making are statistical. We need not assume that the index functioned perfectly in every instance, only that it is good enough for our purposes.

Figure V-1 shows how the four groups compare in terms of their average scores on the index. The striking finding is that the users scored significantly lower than the nonusers, and this result held within each of the ethnic groups.6

It may be recalled that the data just described refer to the family with which the boy resided for the longest time between his tenth and his critical year. The question raises the possibility that the boy lived in more than one household during this period. Whatever the degree of cohesiveness of any of the families involved, the fact of tearing up one's family roots and having to find a place in another family is probably a trying experience to a child and one which may well undermine his sense of confidence in the dependability of other human beings.

Our data on this are for the entire lifetimes of the boys up to the critical year. The differences between the groups are mainly along the lines of delinquency and only secondarily along those of drug use.6 Fewer of the nondelinquents, regardless of whether they were users, had to withstand the trauma of shifting families. If we compare the controls with the nondelinquent users and the delinquent nonusers with the delinquent users, however, in both cases more of the users had been confronted with the task of adjusting to new families.

An important aspect of the stability of the family is the continuity of the boy's relationship to his father. In psychoanalytic theory, the father is the key figure in the development of a boy's moral sense. There are marked differences in the proportions of boys in the four groups who did not live together with their biological fathers up to the critical year. The control group is the most favored in this respect, and the two delinquent groups, least so.7

A related issue is the quality of the boy's relationship to his parents. We asked the boys to indicate the one adult person, among all whom they knew, whom they most wanted to think well of them at the critical age. There were some striking group differences in the answers to this question. Many more of the controls than of any of the other groups specified their fathers or both parents, and the two delinquent groups lagged far behind.8 When those who did not refer to either parent were excluded,8 fewer than half of the controls, as compared to large majorities of the other groups (especially so in the cases of the two delinquent groups), specified the mother alone.10

What of the values transmitted by the families apart from those implicit in the experience of a stable and cohesive family? We have several kinds of data bearing on this question.

We may begin by assuming that a family which includes individuals who are drug-users, alcoholics, or who have been in serious trouble with the law is apt to encounter some special difficulties in impressing on its youngsters the importance of abiding by the standards of society. The differences between the groups were, in general, consistent with such an expectation, although not all were statistically significant. The most impressive difference involved individuals with a police record (i.e., having been sentenced to jail or a reformatory or placed on probation). The families of controls again clearly had the best record on this score, and the nondelinquent users came out second best; the delinquent users, however, came out better than the delinquent nonusers." The safest generalization is that the controls are better off than the other three groups; if any other generalization is warranted, it is that nondelinquents, whether or not users, have the advantage over delinquents.

On the issue of drug-users in the family, each of the user groups came out somewhat worse than either of the nonuser groups, but none of the differences were large enough to justify generalization.12 With regard to alcoholism, the division was, if anything, along the lines of delinquency, each of the delinquent groups reporting a larger proportion of families with alcoholics than either of the nondelinquent groups."

At the opposite end of the behavior spectrum, one may get some indication of the values fostered by the families from the reported regularity of church attendance. The control families were clearly the most churchgoing, with more than three-fifths reported as attending regularly, and only 2 per cent attending seldom or never. By contrast, about half the families in each of the delinquent groups were said to attend regularly, and about one-third seldom or never. About two-fifths of the families of the nondelinquent users were described as regular attenders, and the same number as nonattenders. The statistics for the boys themselves during the critical year paralleled those reported for their families; but, in all four groups, the boys described themselves as less frequent churchgoers than their families."

The presence of deviant individuals in a family is only one of many possible indexes to difficulty in imbuing the young with respect for social norms. We investigated the possibility that the failure of the users and delinquents to abide by conventional standards was related to the fact that their families were less well equipped for teaching their sons the socially acceptable "know-how" because they themselves might have been ignorant of conventional norms, either because they were immigrants or otherwise strangers to the community through geographic or social mobility. This hypothesis was, if anything, contradicted by the evidence.

The proportion of sons of immigrants was highest in the contiol group." In the same vein, the boys who were themselves born abroad (there are twenty-one of them) were found primarily in the control group and in the group of delinquent nonusers; very few boys in the two user groups were foreign-born.16

There remain the native-born boys. Some lived all their lives in New York City. Others had "high mobility";17 they experienced a more-or-less drastic change of environment involving at least a move from one large city to another and, for some, a move from a rural area to a large city. The two delinquent groups showed the greatest proportion of boys whose mobility was high; the control group was least mobile; and the nondelinquent users fell in between.18 The differences were, however, not large enough to warrant generalization.

Several related datp may be gleaned from the study of the families of addicts which is reported in chapters X and XI.19 The families of addicts were residents of New York City for a significantly longer time than were the families of control cases. It does not, therefore, seem likely that the "cultural shock" which recent arrivals to the city might be experiencing is any more conducive to producing a juvenile addict in the family than long residence in a deprived urban area. There was also no difference between addict and control families in the extent of social participation with friends, neighbors, or relatives, in the use of community resources, or in participation in formal organizations.

One final set of data has some bearing on the matters discussed in this section. This concerns the orientation of the families to the future.

There were no differences among the groups in the proportions20 of families in which one or more persons saved money, for whatever purpose. Nor were there any differences in the proportions" of families in which one or more persons were described by our respondents as having actively planned for the future. Nor in the proportions22 of families in which the plans of the boys for the future were discussed.23

The one striking difference between the groups was the frequency with which the boys' plans were discussed. Hardly any of the controls described their parents as nagging or said that these matters were discussed very frequently, as compared to a third or more in the other groups." This does not mean that the parents of the controls were less interested in their sons' futures. The difference can be easily explained in terms of occasion for concern. As will be seen later, more of the control boys had definite plans for the immediate future, and there were a number of other characteristics (e.g., a continued interest in schooling) that would occasion less concern over where they were bound. By the same token, the fact that their own plans were consistent with their parents' aspirations for them would tend to eliminate any flavor of nagging from conversations about such matters, and even frequent discussions would not seem so frequent because there would be no issue made of the future. On the other hand, the common planlessness of the boys in the other groups, their lack of interest in education, and their disinclination to seek or to prepare themselves for steady jobs would provide ample grounds for the issue to arise frequently, and to arise in a way that would make the boys feel that they were being con. stantly hanassed.

An associated difference between the groups, involving the substantive aspects of the discussion of the boys' futures, undoubtedly has the same explanation. Although most of the parents in all of the groups were mainly concerned in these conversations with the problem of what the boys would do occupationally, there were nevertheless significantly fewer of the control parents who focused on this aspect of the matter, and there were more of them who focused on educational matters.25

To summarize: With respect to most of the factors that might be expected to help generate a family climate that would instill in the young respect for societal standards of behavior or that might be expected to have the opposite effect, the controls come out in the most advantaged position and the delinquents in the most disadvantaged position. In other words, most of these factors are, at best, relevant to deviancy in general or to delinquency in particular; they do not suggest any specific clues to factors in drug use. Contrary to our expectations, for instance, the experience of a relatively prolonged deprivation of contact with the father and the choice of the mother as the person whose opinion of oneself one values most are factors most closely associated with delinquency, rather than with drug use.

On two factors that might be expected to be disruptive of the normative system—the immigrant status of the parents or of the boys themselves—our controls actually come out worse than the other three groups; for the boys born in this country, however, a high degree of geographic mobility was associated with delinquency, not with drug use.

Two factors which primarily distinguish delinquents from nondelinquents do have a possible adjunctive role in drug use. When we hold delinquency status constant—Le., when we compare the users with the nonusers among the delinquents and, similarly, among the nondelinquents—more of the extended families of the users in the sample do include individuals with police records, and more of the users have had the experience of living with different families.

The one factor we have found to be distinctly related to drug use and apparently unrelated to delinquency per se is the experience of living with a relatively cohesive family. The users have, on the average, been more-deprived, in this respect, than the nonusers. We have interpreted the value of living with a cohesive family as a contribution to a sense of mutuality.

Material Deprivation

One may argue that social and economic deprivation in the family can be perceived by a child as failure in the legitimate world, as a proof that one cannot win in legitimate ways. One would accordingly expect the two groups of users and the delinquent nonusers to be more deprived in this sense than the controls. Indeed, studies of juvenile delinquents have repeatedly shown that, in comparison to nondelinquents, they tend to belong to socially and economically underprivileged strata in disorganized areas often bordering on "respectable," high-income neighborhoods.26

Does the same hold for drug-users? We already know that they live in the most deprived areas of the city and that, the greater the neighborhood poverty, the greater the rate of juvenile users, even in a generally deprived area. But, in comparison to other youths who have also grown up in deprived neighborhoods but who have not become heroin-users, do the individual users come from the most deprived homes?

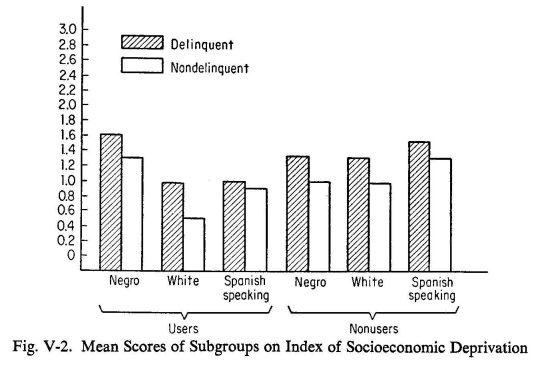

We compared the four groups on an index27 of socioeconomic deprivation based on three items: the dependence of the family on outside financial help; the level of the breadwinner's occupation; and the quality of housing facilities. Index scores range from zero (where all these conditions are favorable) to 3 (where they are all unfavorable). The results for all the subgroups in our sample are given in Figure V-2.

The delinquents are consistently more deprived than the nondelinquents in terms of the index. These findings not only corroborate the work of the Gluecks, but extend their general results to another city at a later period and to three ethnic categories.

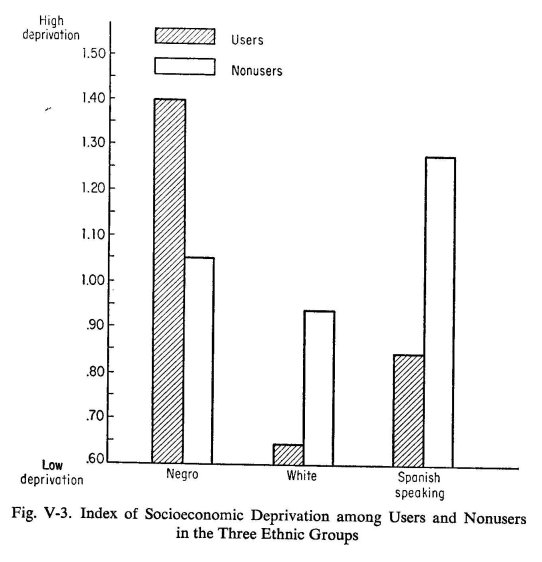

There is, however, no correspondingly clear-cut difference in this respect between the users and nonusers; here, the three ethnic groups present varying pictures. Although the Negro users are more deprived than nonusers, the situation is reversed among both whites and Puerto Ricans; the users come from homes of better socioeconomic circumstances than do the nonusers! (See Figure V-3.) We can advance no explanation of the differing patterns that is both plausible and simple.

The finding should, however, give pause to one inclined to interpret the correlation between neighborhood poverty and the incidence of drug use as signifying that poverty per se is conducive to drug use. It may be recalled that we have interpreted the correlation not in terms of the direct impact of poverty on the youth, but in those of the community atmosphere. The youngsters react to the values and practices they experience and not simply to the material deprivations from which they suffer. The most vulnerable are, at least among the whites and the Puerto Ricans, not those from the poorest families in their neighborhoods.

It may be that there is something particularly pathogenic about the somewhat better-off family which stays in the deteriorated neighborhood voluntarily—what, if anything, we do not know. If this were the case, it would not be relevant to the Negroes who experienced extraordinary difficulties in breaking out of the Negro ghettos.28 If such an explanation were sufficient, however, we would expect that there would simply be no relationship among the Negroes between the material circumstances of the family and drug use, rather than the definite relationship that was found.

It is, of course, also possible that there is something special about the group of Negro users, and, in fact, there are a number of reasons that lead us to take this possibility seriously. First, it may be noted that the index of socioeconomic deprivation is highest for the Negro users, but we also suspect that there is among them much less personal psychopathology conductive to drug use. Reference to Figure V-1, for instance, shows that the gap between the Negro users and nonusers with respect to family cohesiveness is smaller than that for any of the other groups and that the Negro nondelinquent users are, in this respect, better off, on the average, than members of any of the other ethnic user groups. The Negro users were also the slowest to reach a point of regular daily use; the majority took more than a year from the time of their first trial, whereas the majority of the other two ethnic groups took less than a year. The Negro users in our sample were more exposed to the drug-using pattern than the other two groups; they came from the highest drug-rate areas, and more of them had a drug-user in their families. Even among the nonusers, most of the Negroes had a chance to try heroin, as compared to about half the boys in the other nonuser groups. If we may generalize the findings reported in Chapter IV, the drug-using subculture is much more pervasive in the Negro high-use areas. Finally, we may mention the fact that more of the Negro users than of the others stressed conformity as a reason why boys become users—"to follow the fad," "to be down with the rest of the cats," "so the other cats won't think you're chicken" are some of the typical reasons they gave.

In other words, we are suggesting that, whether the users have a history of prior delinquency or not, drug use among the Negro members of our sample is most closely linked to factors conducive to delinquency rather than to drug use as such.29

To recapitulate the rather tortuous and, at best, incomplete explanation of the differing relationships between the index of socioeconomic deprivation and drug use: The families of the white and Puerto Rican users do have considerably greater freedom than do the families of the Negroes to move away from the unwholesome neighborhoods in which the children are growing up, and their materially better circumstances put them in a better position to do so. The fact that they do not suggests that there may be other things wrong with these families that have not been tapped by our investigation—perhaps that they are little concerned with the welfare of their children—and that are particularly associated with vulnerability to drug use. The Negroes, however, are immobilized by residential segregation so that the failure of the better-off families to move away can have no possible diagnostic significance. On the other hand, drug use among Negroes is more intimately related to delinquency and accompanies more marked socioeconomic deprivation, just as does delinquency.

Adolescent Stress

Adolescence is a transition from childhood to maturity, and the stresses peculiar to it stem from problems of transition. The adolescent wants, in many ways, to be treated as an adult and, in others, to retain the relationships of childhood. The adult world also wants him to act as an adult in certain ways and as a child in others. Trouble arises from the facts that, where the teen-ager wants to be adult, the adult wants him to be a child and, where the adult wants him to be adult, he wants to be a child.

The teen-ager, for instance, typically wants the freedom that is to him the essence of adult status—freedom to come and go as he pleases, freedom to engage in sexual relations, freedom from the need to give an accounting of his actions, freedom from the supervisory eyes of adults—but he is not ready to accept, and often does not appreciate, the responsibilities that go with such freedom. The adult, on the other hand, wants the teen-ager to act with increasing responsibility, but he is not willing to grant the youth the freedom he craves.

It is not that people—adolescents, adults, or both—are contrary. The adolescent is impelled by his maturation, the emergence of his sexuality, the widening of his horizons, the incitations of his fellow teen-agers, the imminence of the time when he must stand on his own feet, the very urgings of the adults around him to act as a grownup. The adult, on the other hand, is all too aware of the dangers that go with freedom —dangers to which, he is with some justification convinced, the youngsters cannot be fully sensitive and dangers which are enhanced by the impulsiveness and inexperience of youth. Even apart from their own emotional investments in the welfare of their children, adults retain legal responsibility or social accountability for the actions of their children.

Nor is the conflict entirely between the teen-ager and the adult. To a considerable degree, a similar conflict goes on within the adolescent himself. Freedom, as Erich Fromm has noted,3° can be terrifying if it is not accompanied by assured competence and clarity of destination. The teen-ager, therefore, counts on the adult to keep him within bounds and on a safe course, and the very controls against which he so vigorously rebels are essential to his sense of security. His burgeoning impulses impel him to defy restraints, but they also threaten the integrity of his selfhood, for the very vigor and inchoateness of his impulsive life threaten to engulf him and sweep him into depths in which, for all he knows to the contrary, he may never be able to resume control.

Moreover, with the imminence of the time when he must stand on his own, the issues of the self—who and what am I? where do I belong? what shall I be? what goals, what restrictions, what behavior am I to accept as appropriate for me and what am I to reject as not fitting? —become extraordinarily acute. The adolescent is impelled to define a distinctive identity for himself and is, at the same time, full of too many conflicting possibilities to be able to commit himself to one identity. He needs the shelter and the restraint of an understanding adult to give him the freedom to experiment with personal identities and the assurance that no one act or series of acts necessarily represents the final commitment." To the observing adult, he may seem immersed in a struggle to seize (prematurely, from the adult's viewpoint) the requisites of the adult status, but, consciously or unconsciously, he dreads being abandoned to adulthood.

The stresses of transition are, of course, not equally grave or intense for all adolescents. The factors, internal and external, that give rise to the teen-ager's bids for adult status do not impinge on every individual at the same rate or with equal force, nor do they find all equally unprepared to cope with them. The suddenness with which he is confronted by his budding sexuality, for instance, and the effectiveness with which he has dealt with the problems of earlier stages of development are only two of the things that make a difference in the teen-ager's readiness to take on the new problems of adolescence. Moreover, the adults with whom the teen-agers have to deal are not equally flexible and understanding, equally concerned with the welfare of their children, equally prone to project their own unresolved anxieties onto their children or to treat them as instrumentalities of their own efforts at adjustment.

The current environment of the adolescent may also make the transition more or less difficult. It may provide support or add unnecessary frustration. It may clarify or confuse, help or obstruct. The five major facttirs identified by Cottre1182 as facilitating the adolescent transition are, in the main, aspects of the concurrent environment. The factors identified by Cottrell are: (1) the presence of a male adult who acts both as an ideal and as a guide and interpreter, (2) imaginary or actual rehearsal for adult roles, (3) opportunities for respite from tensions, (4) consistency of expectations, and (5) provision of adequate paraphernalia of adulthood. Note that all but the second refer to some aspect of the adolescent's environment and that, even with respect to the second, it is largely the current environment that instigates the daydreams that constitute the imaginative rehearsals for adult roles and that contributes the stuff of which these dreams are made.

We did not think of inquiring into these matters until after the two user groups and the delinquent nonusers had already been interviewed. We did, however, raise the issues with the controls and with the second sample of Riverside cases. The questions all concerned the critical year.

ADULT FIGURE IN BOY'S LIFE

The differences we found between the two groups are limited to rather subtle aspects of the boy-adult relationship. In general, both groups are alike in that roughly one-half of each group said that they knew, or knew of, some grownup whom they wished to be like. Of the latter, about 15 per cent said that this person was their father, about a fifth mentioned some other related male, and the rest referred to public figures in the world of sports or music, or to teachers, ministers, older friends, and the like.

The boys in the two groups who designated some ideal adult differed, however, in what it is about the latter which they wish they could emulate. The control group mentioned personality attributes (such as kindness or courage) much more often than did the user group;33 the users tended to mention more often attributes with material implications, such as wealth or skills.34

Similarly, there is no difference in the proportion of boys in each group who voluntarily sought out some adult to discuss a personal problem—about two-thirds in each group. However, in the control group this was more often the boy's own father or teacher or priest; in the user group, slightly more boys mentioned older brothers.35

Most of the boys in both groups who sought out an adult felt that they "could really be open" with this person, and most of them claimed that they "usually felt better" after a talk with him. They talked mainly about school problems (the control group mentioned this more often than did users),36 sex, work, and future education. A few also discussed family problems, and there were small numbers discussing a host of other matters, such as the draft, how to deal with people, immediate financial difficulty, and so on.

The help given by the adult to the users consisted largely of advice. The boys in the control group also mentioned receiving advice, but less frequently," and a few mentioned other forms of help, such as the adult encouraging their decisions or being helpful by showing understanding.

RESPITE FROM TENSIONS

The boys were asked: "Was there any place where you felt especially easy and relaxed and free from worries?" More of the users than of the controls said that they had such a place." Of those who had such a place of escape, twice as many users had a club or other specific place where they met with friends. Even so, most of the boys in both groups usually whiled the "blues" away outdoors, at home, or at the movies, without, however, indicating whether they were with friends; only a small minority specified that they sought refuge in solitude.

On the face of it, the advantage lies with the users; but it is also likely that more of them needed a special place in which to relax. Much of the data already reviewed from the four-group comparisons (e.g., the data on family cohesiveness) suggest that home was a more comfortable placé for the controls. Another datum that points in the same direction is the fact that many more of the controls' parents approved of their sons' friends whom they brought home." Similarly, fewer of the nonusers reported that they were "yelled at" at home or punished by rejection —ordered out of the house, locked up, ignored.4° Another factor that points to the relative unimportance of a place of refuge, also from the four-group comparisons, is the quality of the boys' friendships. The control group reported more stable and intimate friendships.41 Thus, the significance of the finding seems to be in the fact that more of the users could identify a particular place where they could relax, rather than the apparent relative deprivation of the controls in not having such a place.

CONSISTENCY AND TIMING OF EXPECTATIONS

We asked the controls and the boys in the second Riverside sample how old they were when their families "started treating you as a man—you know, expecting you to be independent and make your own decisions and make your own living." Since the age at which the users became seriously involved with narcotics might make a difference in this respect, we compared the controls (for whom the critical age was, by definition, sixteen) only with those users for whom the critical age was also sixteen (there were twenty such). The users reported having been treated as adults considerably earlier than the controls."

We also compared users and controls, matched on a person-to-person basis for age at the time of the interview, since age at the time of reporting might make a difference in the retrospective dating. On this basis, we had twenty-four cases in each group. Again, the users placed the age at which they were first treated as adults considerably earlier than did the controls.43

It is, of course, possible that the users were exaggerating their youthfulness at the point of achieving "maturity" (or exaggerating more than did the controls); some dated the event at fourteen and even earlier. The difference between the two groups shrank below the level of statistical significance, however, when we added the question of whether they were also treated as adults by others outside their families (e.g., by teachers or tradesmen) .44

If we were to take these findings at face value, it would seem that, in terms of the adolescent's striving for independence, the user finds the transition to adult status easier than the control. There is, however, also the other side of the issue—responsibility—and the question places heavy emphasis on this aspect. In fact, expecting such youngsters to make their own living is carrying the "privileges" of adulthood to a rather extreme point. We may, therefore, suspect (still taking the findings at face value) that the earlier age of achieving adult status represents a desire on the part of the parents to shirk their parental responsibilities rather than a genuine respect for the maturation of their sons. On this interpretation, the premature granting of adult status is an act of rejection rather than one of affirmation.

This speculative interpretation is in line with the findings of a lesser degree of cohesiveness in the users' families. It is also in line with an associated finding. The granting of adult status is more likely to be associated with some other objective status change among the controls than among the users,45 as in connection with graduating from school, getting a job, moving out of the house, or the like. The control is apparently more likely to win his maturity by, so to speak, passing a test; he has in some sense proved himself. The user, by contrast, is more likely to have won his maturity for no obvious reason—an indication that his parents may not have cared enough to withhold it from him.

Even so, and despite the apparent delay, more of the controls were ready to confess that they did not greet the adult status, when it did come, with unalloyed joy. More of them said that they did not "feel up to it all the time," and more of them would have preferred to be still treated as a child most of the time." Thus, it would seem that, at least for the boys in the sample, the controls were more likely to experience subjective difficulty in the transition to the adult status than were the users. In this sense, they may be said to have matured less rapidly. It seems likely, however, that, if this is in fact the case, it is so because the users were already accustomed to being left on their own. It does not mean that the users were actually better prepared to assume adult roles. The sheer fact of their involvement with narcotics stands as testimony to the contrary.

As we have already indicated, the ambiguities of the adolescent status are not arbitrary impositions on the developing youth. They are, to some degree, necessary counterparts of maturation. The process may be eased by tolerant understanding on the part of the parents and by the graduated character of their expectations. The process cannot be eased, although it may be curtailed or aborted, by the parents' abandonment of their roles and the ejection of the child from their concerns into a world which offers no support, guidance, or love on which, if need be, the fledgling might fall back. The users may not have felt the transition so keenly, but the indications are that this is not because the transition was easier for them; it was, in large measure, because they were deprived of the transition.

In other words, we are suggesting that, if more of the users than of the controls described themselves as content with the transition, this is only because discontent was to them a normal state of affairs and „because they had no image of the possibilities of greater contentment. That this is the case is also suggested by another set of data.

We asked the boys, in a probing, direct way, about their life in the critical year: "Did anything unusual or special happen to you at that time? Was there anything that was bothering you or worrying you? Did you have any discouraging experiences or experiences that were very exciting? Was there something that you especially wanted but couldn't get?"

In general, the boys mentioned various unfulfilled desires as things that bothered them; and a fair number mentioned events that signified maturity, such as graduating from school or getting a job, as exciting events. The users differed from nonusers in two respects: over half the delinquent users47 had been "in trouble with the law" during the year; and about a fourth of both user groups had experienced some radical change in their situation—such as moving to another neighborhood, separation from or death in family, shotgun marriage—as compared to only 4 per cent in the control group.

This last difference supported our expectation that, at least for a large number of the youths, the onset of habitual intake of heroin was accompanied by greatly upsetting events and inner strain. Yet, when we asked the boys, "How would you describe your life in [that year], in just a few words?" and "Would you say that you were happy, fairly happy, or very unhappy?"—the users showed a tendency to deny that the critical year was difficult or painful.

A majority of the boys said that their life at the critical age was "good"—carefree, active, or just in general good—the users slightly more often than controls. Very few said that it was a bad year. Similarly, in answer to the second question, most boys said that they had not been unhappy that year; but whereas the controls tended to say "fairly happy," the users tended to describe that year as "very happy." Note that the users did not deny the stressful experiences, nor did they paint a particularly rosy picture of the happy experiences of that year. They simply seemed to have a defective sense of what it means to be "very happy."

The differing rates at which the users and the controls are projected into adult status are manifested in many ways. Despite the later age at which they said they were expected to act like adults, less than half as many of the controls as of the users described themselves as financially independent at that point.48 Most were still in school. Correspondingly fewer felt that they had enough spending money.49 Still another indicatiOn of the impulsion to assume adult roles for which they were not well prepared is the larger proportion of users with "steady" girl friends at the transitional age." The point is especially significant because, as will be seen in later chapters, one of the most characteristic problems of addicts is precisely in the confusion over their masculine identities. In other words, their taking steady girl friends at an earlier age occurs despite their lesser readiness for normal heterosexual relationships.

The Environment of Peers

The adolescent does not, of course, live in a world composed of, and defined by, adults. A major feature of his environment is the peer group. This group is an important source of influence and constraint in the choice of patterns of behavior. It provides cues and miscues to opportunities for and consequences of gratification of impulse and of longer-range aspirations; it generates opportunities and consequences of its own; it provides a variety of temptations and instigations; it provides its own rewards and punishments; it provides a panoramic view of possible responses to adult demands, expectations, and prohibitions, of strategies of compliance with and evasions or defiance of adult pressures; it provides an assessment of the "normality" of particular adult pressures, both in a quasistatistical and an attunement-to-"reality" sense; it provides a refuge from the adult world; it provides a feeling of "belonging" based on one of the most potent agents for forming human bonds, the condition of being in the same boat.

The effect of the peer group is not unilateral. To begin with, any area offers a number of peer groups to which an individual can attach himself—groups differing in activities and values and, hence, in the kinds of cues, instigations, supports, constraints, opportunities, and so on that they provide. In attaching himself to one rather than to another, he selects the environment that will influence him. That is, in the very process of choice, he reveals the influences to which he is more-or-less open. Moreover, once he has made his choice, he can, through his participation, help to shape the character of the group, contributing to-, its mood, its value emphases, its polarities, and so on.

The process of choosing is not necessarily final. It involves a number of two-way test interactions. In the end, however, it depends on the variety of groups available, on the individual's preferences, and on his acceptability to the group of his choice.

In the remainder of this chapter, we shall attempt to throw some light on these three determinants of the user's peer-group membership.

DELINQUENT AND NONDELINQUENT POLARITY IN JUVENILE STREET CULTURES

The areas of high incidence of drug use have high juvenile-delinquency rates and a comparatively high proportion of youngsters expressing to some degree an orientation to life that has been described as characteristic of delinquent subcultures. It is, of course, not true that this orientation is the most frequent one in such an area. There are many youngsters, perhaps a considerable majority, in even the most delinquent areas who do not share these values, attitudes, and outlooks. Many of the latter espouse largely conventional, middle-class values, attitudes, and aspirations. Some may aspire to get out of the neighborhood, and others may not, planning instead to follow some legitimate career where they are. The values and life style of these two groups obviously differ in crucial ways.

What, then, were the choices of peer cultures that our group of usersto-be could make? Although we did not conduct an actual community survey in high-drug-use neighborhoods, we may take the profile of the life style of the two nonuser samples—the delinquents and the controls—as a reasonable approximation of the life style of the peers with whom the two samples of youths associated in their natural street and school habitat. Our study of gangs, to be described in Chapter VII, also produced considerable information on the delinquent peer groups.

In labeling these two subcultures, we use the designation often mentioned by the controls and by the other groups alike: the delinquents are those who, in the view of the control group, are "headed for trouble," in their own view, "cats." The law-abiding youths perceived themselves as those who "stay out of trouble"; those who are headed for trouble often call them "squares."

In reality, the lines of division are not sharp. There are doubtless many boys in these neighborhoods who are in between the "cats" and the "squares." Our sampling procedures were designed to get at the two extremes. We do not know much about the middle group. They are presumably under considerable cross-pressure. Quite possibly, they vacilfate—engage in some delinquency; have associates of both types; are somewhat estranged from the idealized middle-class values, yet not in open rebellion. The two "ideal" types should be seen as poles of attraction and repulsion in the social climate of the street; the in-between boys are probably very numerous.

THOSE WHO ARE "HEADED FOR TROUBLE"—THE "CATS"

The most striking aspect of the life style of boys who are in conflict with society—whether they are adjudicated court delinquents in a training school or roaming the streets in a "delinquent" gang—is aimlessness, a lack of order and meaning in their lives. This aimlessness is accompanied by random efforts at creating some pattern and meaning in their existence.

When they were about sixteen years old, the fifty institutionalizedn delinquents spent most of their time "just hanging around"; "goofing off"; going to movies and parties, or "sessions"; playing cards or pool; in sports; and going to parks or beaches in the summer. Most of them (over 80 per cent) had left school by the time they were sixteen. There was little talk among them about planning for their future; in fact, most of them did not know anyone who planned or saved for the future. But they did know people—friends or family—who believed that "a person should get as much fun as he can now and let the future take care of itself"; most of the people around them were of that sort.

Although, at that age, only about a third of the boys had some plans for following a specific occupation in the future, even these plans and their ideas as to their implementation were vague or conditional on some uncontrollable events.

On the other hand, most wanted things in the immediate future—mainly clothes, a car, other possessions, or just money; a few wished for a different way of life and travel.

About a third of these delinquent boys had belonged to regular gangs; but mostly they "went around" with one or two close friends.

The style of life of youths observed in the natural gang setting52 fits into this picture, with the addition of special types of activities typical of delinquent gangs. Although there is much variation among the eighteen gangs observed, certain preoccupations are typical. There is gambling (averaging about once a week); sexual delinquency (about once inr six months), usually lineups, that is, successive intercourse of a group of boys with the same girl; group-organized robberies or burglaries (about twice a month); vandalism and general hell-raising (about once a month); gang warfare (about once in three months). The gangs typically also organize house parties (about twice a month) or dances (once a month), engage in active sports (once a week), and watch sports events.

But most of the time the boys "hang around." Even though all these gangs were among the most troublesome and each had a Youth Board group worker assigned to it, five of the gangs were described by the worker as not having interest in anything, being in constant search to avoid boredom, suffering from a sense of "not having anything to do or place to go." This search commonly leads to an interest in "kicks" and a readiness to try anything for a kick."

About 10 to 20 per cent of the 305 boys in the eighteen gangs we studied were heavy drinkers of wine, whiskey, or both. Most had neutral, tolerant, or positive attitudes toward the use of marijuana, and a large proportion were quite tolerant about those among them who occasionally used heroin.

In Chapter VII, we give fuller consideration to the position of the heroin-user in the delinquent gang. Here, the only factor we want to emphasize is that the delinquent subculture in general and the delinquent gang in particular are hospitable to experimentation with any new, exciting activity, including the taking of addictive drugs.

However, this hospitability should not be taken to imply a strong pressure to try drugs. Most youths who belonged to delinquent subgroups have opportunities to try the drug, but not all do try.

Of the fifty delinquents we interviewed who were not opiate-users, two-thirds had had an opportunity to try such drugs, usually in a group or through a friend, mostly when they were about sixteen years old; however, only four tried. These four did not continue, because, at best, they felt "no kick" or, at worst, they felt "sick" after they tried.

THOSE WHO "STAY OUT OF TROUBLE"—THE "SQUARES"

Our knowledge of the life style and attitudes of the nondelinquent subcultures in the deprived areas is based on interviews with the controls. As already noted, these boys grew up in extremely deprived areas," but stayed out of trouble; they did not become court delinquents or chronic truants or chronically acting-out "trouble-makers," and they were not habitual users of any drugs, including marijuana.

One feature of their life which probably greatly influences their activities and interests is their schooling. Only five had left school before they were sixteen (in contrast to the delinquents, almost all of whom left school that early),55 and almost all had more than ten years of schooling (in contrast to only one-fourth of the delinquents) ; in fact, one-third went to college, although only two stayed beyond the second year. Almost all held some job after sixteen and managed to stay on the job at least half a year. In consequence of all this, they had much less time to "goof off" and "hang around" when they were sixteen (the "critical" year) ; only a third mentioned "goofing off" with friends (compared to two-thirds of the delinquents) and less than half mentioned "hanging around a candy store" (compared to about three-fourths of the delinquents). For half of them, the most common way of spending leisure time with friends was to engage in active sports; others mentioned going to community centers, parks, and beaches. Although, like the delinquents, most had one or two intimate friends, they also tended to belong to small cliques, rather than to large, organized gangs; most had known their friends for many years.

Half the boys had definite short-range plans, mostly concerning preparation for an occupation (the delinquent boys' plans had been mostly vague, and a sizable proportion planned merely to enter the Army or to get married).

Though many wanted things they could not get at the time, very few wanted merely clothes and a car (as did the delinquents); over a third wished for a different way of life and over half wished for a variety of special possessions (bicycles, cameras, and the like). Among their friends, most of the boys said, there was not much talk about wanting a car, clothes, or much money.56

About three-fourths said that they read books and enjoyed reading (half, very much so); a large majority used the public library; they read up to five books a month; most said that they occasionally discussed books among friends, though few claimed that they did much of that.

About half the boys were interested in extracurricular activities, and most of these took active part in such activities.

Though most of the youths dreamed of traveling, most realized that their chances for travel at that time were slight and admitted that they hoped rather than planned to travel; their friends did not talk much about travel.

In summing up their life in the critical year, most control youths said that it had been a good year or an average one; most said that they were fairly happy at that time. Asked to tell us about the important events in their life that year, one-third of the boys mentioned having learned some new skill; hardly any of the delinquents mentioned this.

The picture that emerges is a very rough profile, yet one that is in very sharp contrast to the delinquent profile. These boys are not at odds with the major institutions; they do not drop out of school, and many manage to hold a job. Their general orientation at sixteen was reasonably realistic in that they had some sort of definite plan for the immediate future, and they did not wish for things they knew they could not possibly get. Their relation to their environment was positive in the sense that they were interested in and able to utilize available opportunities, such as extracurricular activities, to their enjoyment and benefit.

The boys were quite familiar with such addictive drugs as heroin. By the time they were sixteen years old, most had heard about such drugs (a third, when they were fourteen or less). By sixteen, most had also seen someone use heroin and had certain beliefs about addictive drugs—of the kind that would make one hesitate before using drugs. Most mentioned that drugs impair health and the mind, that they are costly, or that they create dependency. (It is striking that the delinquent boys mentioned the same reasons in almost identical proportions.)

Forty per cent (compared to two-thirds in the group of delinquent nonusers) had a chance to try heroin, in the main when they were sixteen years old. The opportunity was usually presented by a peer who offered to give or sell the drug; the offer took place on the street, at a party, or at school. None of the boys tried the drug. The main reasons for refusing were a sense of wrong in taking drugs; belief that drug use is bad for one's health; and fear of getting into trouble with the law. Two boys said that someone else had urged them not to try it at the time they had the opportunity, and they listened. Eight of the control boys did have a try at smoking marijuana, mostly in a group, at a party; but they never smoked it regularly.

What is important for us here is that the subculture of those youths who "stayed away from trouble" was not hospitable to experimentation with addictive drugs; in fact, drug use does not seem to have had a meaningful place in these boys' current lives and future plans. Opportunities to try heroin arose less often than among delinquents, and the boys were not likely to give heroin even one try.

Before we look at the position the users occupied in their peer subcultures and try to establish a connection between the nature of peer associations and the first step toward addiction—experimentation—it may be of interest to examine the interaction between the clearly delinquent and "square" subgroups, the pull and push, attraction and repulsion that goes on between them.

HOW THE TWO SUBCULTURES VIEW EACH OTHER

The "cats" and the "squares" live side by side on every block of the slum area. In answer to our question, "What kind of guys were there in your neighborhood?" most of the controls57 gave a picture of rather well organized and strongly differentiated groups of adolescents. They mentioned ethnic groupings and degree of organization (gangs and bunches). But, most importantly, one-third mentioned "tough" gangs, and another third, "tough guys," as opposed to those who "kept away from trouble."

The over-all pressure of street associations seems to be in the direction of alignment with the "fast crowd" of noisy, aggressive "toughs," or "cats."58 The dominance of the "fast crowd" in the street culture was strikingly described by one of the "square" boys who said that, "in a neighborhood like ours, it's never convenient to carry books. • . One of my friends quit high school because he didn't want to be seen with books." This may be a gross exaggeration of an actual event, it may represent a local myth which the narrator believes so strongly that he offers himself as a personal witness to emphasize its truth, or it may actually have happened, albeit as an extreme case; in any event, it stands as testimony to the "squares'" perception of the streets as dominated by the "toughs."

The "squares'" position in the street culture may be described as "contact but not involvement." Most of the control group had some friends who had been in jail, reformatory, or on probation. However, only a sixth had intimate friends of this kind, compared to half of the delinquents. In answer to our question, "How did you feel about these different groups?" over half the control group expressed negative (deprecating, hostile, or both) attitudes to the "others" among their peers who were not their close friends; the rest were largely indifferent. Often this rejecting attitude was expressed with a great deal of affect. In the words of one: "I just passed them up. Didn't want to associate with those little dirty-mouthed bums. They were headed for trouble." A majority spontaneously mentioned that, at the critical age of sixteen, they had no contact with the "others," that they made it a point to stay away; the association was dangerous. As one youth put it: "You are afraid of them—not physically, but because being with them can get you in trouble if you are close to them. I couldn't endure no penitentiary."

The control group's sharper awareness of the presence of the "toughs" in their neighborhoods and the effort to dissociate themselves from those who were "headed for trouble" is also reflected in a more purposeful selection of friends. In answer to our question, "How did you happen to fit in with [those] guys rather than the others?" a majority indicated that they picked their associates for common interests, for protection, or for other specific reasons.

Whether this dissociation from the "toughs," so firmly asserted by the bulk of those who managed to "stay away from trouble," indicates that the values, interests, and activities of the delinquent subgroup had no meaning or negative meaning for them or merely that they were more aware and apprehensive of the risks entailed by such associations, we cannot say. It is sufficient to say that in the deteriorated areas where drug use flourishes, there are subgroups of "tough" adolescents whose alienated style of life is hospitable to experimentation with drugs; there are other subgroups that stay clear from the "toughs" and in general steer away from trouble with what one senses is grim determination. Our main interest is, of course, in the drug-users; where do they fit, by virtue of their preferences, interests, and capacities?

The Future Users: Preferences, Interests, and Associations

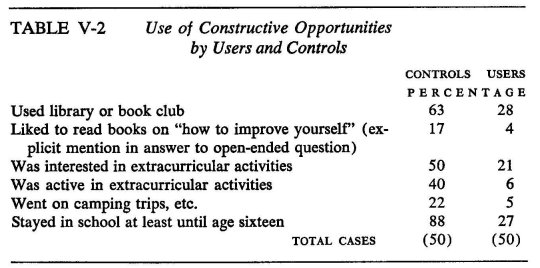

An examination of the users' interests and general style of life in the year preceding onset of drug use" reveals more similarity to the "tough" subgroups than to the "square" ones. For one thing, the users made less use of libraries, extracurricular activities, and some of the less common leisure activities than did the control group. They left school earlier, and fewer of them received on-the-job training. Table V-2 shows the differences between users and controls in extent of utilization of constructive opportunities.

These differences between the users and controls are relevant here not as indicators of health or pathology but, rather, in their implied consequences. The "squares" explored certain avenues where the iisers seldom ventured; there would be, consequently, less likelihood for the users to meet the "squares" on some common ground outside school.

On the other hand, the future users' mode of spending leisure time was likely to bring them into frequent contact with "those who were headed for trouble"; like the delinquents, the users often mentioned going to movies; hanging around candy stores;6° goofing off; and going to "sets," or parties and dances.

In the second sample of users, one-fifth reported that their life at the critical age was inactive; hardly any of the control group gave this response.

Concerning their wishes and interests at the critical age, all users were similar to the delinquents in their frequent mention of a desire for better clothes. However, the users do not appear to have perceived themselves as closer to the "toughs" than to the "squares." In fact, they seemed equally distant from both.

Their distance from both extremes is evident in their attitudes to the "different types and groups" in the neighborhoods in which they lived at the time they started using drugs. Following the question about what "different types and groups" were to be found in their neighborhood, we asked the boys, "Where did you fit in?" and then, "How did you feel about these different groups (the `others')?" The reader will recall that the control group, which tended to mention more of the antisocial groups and individuals than "respectable" groups and individuals, expressed negative feelings toward the "others," who, as is clear from their comments, were usually the "tough" ones. The controls also indicated, in a variety of ways, a determined effort to stay away from those "others" who might "get them into trouble." Nearly half the users, on the other hand, expressed neutral or even friendly feelings toward the "others," and few expressed distinctly negative feelings. It is clear from the comments accompanying their statements of feeling toward the "others" that, for the users, the "others" were the "respectable" groups, the "tough" ones, or, in some cases, both. Their positive attitudes expressed a detached tolerance of them all. In fact, the most common answer was: "They were O.K. I got along with them all."

This nonpartisan, passive attitude was also reflected in the way they selected their friends. Whereas the majority of controls claimed that they selected their friends for one or another reason, few users mentionia picking friends; the great majority said that their friends were boys with whom they just happened to grow up in the neighborhood or met at school.

The users' description of the boys they went with differs from that given by the controls in the direction typical of the delinquent orientation. A majority of the users, but only a minority of controls, reported that, among the "fellows they went with" at the critical age, there was "a lot" of talk about "real expensive clothes" and that their friends talked "a lot" about wanting to have a car and pocket money.

On the other hand, when asked, "Among the fellows you went with, was there talk about guys who knew a lot about current events, books, art, and such things?" a majority of the users, compared to only a fourth of the controls, said: "No, never." When asked, "Did the fellows you went with talk about the things they read?" over half the users, compared to a third of the controls, said "Never."

In all these statements, the users show their friends to be consistently aligned with the kinds of activity and concern that was shown earlier in this chapter to be typical of the delinquent subculture. These were the boys they went with before they started using drugs regularly. As we examine, in the next chapter, the process of becoming a habitual user, we shall see that the first step is usually taken in casual association with peers who condoned experimentation with drugs for "kicks."

STATISTICAL FOOTNOTES

a See Appendix J.

b Disqualified "for cause" were 13 per cent of the Negro boys, 13 per cent of the Puerto Ricans, and 7 per cent of the whites; the variation was not, however, significant at the .05 level by the chi-square test. Disqualified because of noncooperation by social agencies were 10 per cent of the Negroes, 11 per cent of the Puerto Ricans, and 5 per cent of the whites.

c Of the 425 letters sent, eighty-eight were returned as undeliverable, i.e., the family had moved and left no forwarding address. There was a significant difference in this respect between the three ethnic groups-40 per cent of the Puerto Ricans, 22 per cent of the Negroes, and 11 per cent of the whites.