3 Social and Economic Correlates of Drug Use

| Books - Narcotics Delinquency & Social Policy |

Drug Abuse

III Social and Economic Correlates of Drug Use

Drug use is, as we have seen, not evenly distributed over the city. This fact, in itself, does not provide many clues to the factors making for drug use. It may be regarded as not so much a fact in its own right as a directive to investigate the lines of neighborhood differentiation corresponding to the differentials in drug use. But there are probably no two neighborhoods—i.e., census tracts, in the present investigation—exactly alike in all respects. In other words, the number of possible differentiations is certainly very large, perhaps even infinite. What lines of possible differentiation shall we, then, select for investigation?

Some suggest themselves by an inspection of the map and an impressionistic acquaintance with the city. Thus, it appears that the areas of highest drug use are areas inhabited, in the main, by certain ethnic groups. This suggests that relevant dimensions of neighborhood differentiation are the proportions of Negroes and of individuals who (and/or whose parents) came to the city from Puerto Rico. Similarly, it appears that the areas of highest drug use include some of the city's worst slums. This suggests that we look at some socioeconomic indexes, such as proportion of low-income families, proportion of households without television, proportion of unemployed males, proportion of employed males employed in so-called lower occupations, proportion of highly crowded dwelling units, and the like.

Some lines suggest themselves on the basis of the general theory of social pathology and studies of other forms of deviant behavior (e.g., juvenile delinquency). To some extent, this basis would lead to the same kinds of variables as those already mentioned, but the focus is quite different and calls attention to additional variables. Thus, we would be concerned with variables related to the potency, stability, pervasiveness, coherence, and need-satisfying sufficiency of social norms; the standards of behavior which individuals learn and internalize through precept and example; the rewards or gains (e.g., parental and other social approval) that come from abiding by them; and the punishments or losses that come from deviating from them.

Uprooted populations tend to show disruption of the normative patterns. This suggests such variables as proportion of the population which has recently changed its places of residence, and it calls attention to such variables as proportions of Negroes and Puerto Ricans because large sections of these populations have migrated in recent years.

Similarly, the intrusion of business and industry into residential areas tends to disrupt the normative patterns, perhaps because it tends to bring with it a floating population and sources of power without "roots in the community, social mobility, restlessness, and so on. Hence, the relevance of such variables as the relative number of employees in large establishments and the number of business establishments per block.

The family unit is perhaps the major agent of society for the transmission of social norms, especially in individuals' formative years. This would lead us to expect that areas with high incidence of disrupted normal family living arrangements would also be areas of highly disrupted and relatively impotent normative patterns. Hence, the relevance of such variables as the proportion of married individuals living apart from their spouses, proportion of individuals not living with their families, proportion of married couples not living in their own households, and proportion of women in the labor force. Again, such variables as poverty and migration come into the picture because these variables are not unrelated to the degree to which individuals can establish ideal family living arrangements. Indeed, any variables which can have impact on social norms are relevant from the viewpoint of family arrangements because the family is itself a complex, normatively regulated social institution.

Still another way of looking at the potency, stability, pervasiveness, and coherence of social norms is to determine the degree to which these norms have functionally adaptive values to the individuals governed by them. As Robert Merton has pointed out,1 if the normative system emphasizes certain goals (e.g., owning a car, having an attractively furnished home, a prestigeful occupation, and so on) and there is, at the same time, an insufficiency of legitimate means of attaining these goals, then one may anticipate a variety of forms of breakdown of the normative system. This directs attention to such variables as poverty and to the minority groups which are especially underprivileged by virtue of the discriminatory practices they encounter in housing, employment, education, and other matters.

Another possibly relevant line of social differentiation is suggested by the age group we are studying. This is the "density" of the male adolescent population. The greater the density of the male adolescent population, the greater is the probability, other things being equal, of a multiplicity of contacts among teen-aged boys and mutual reinforcement in their behavior patterns. If this happens, it is not unreasonable to assume that there may be a corresponding decrease in the average degree of adult control over teen-age behavior. That is, it is possible that, the greater the density of the male adolescent population, the more autonomous does the behavior world of the teen-aged boy tend to become. Also, the spread of teen-age fads (of which experimentation with drugs may be an example) may be facilitated by the density of the teen-aged population.

Another possibly relevant line of social differentiation was suggested by the psychological study of drug addicts. Addicts have been described as having passive personalities and, even more to the point, being confused with regard to their masculine roles. We thought it possible that a preponderance of females in the environment might, if not cause such personality orientations in the first place, at least contribute to their maintenance. Hence we felt it desirable to investigate the ratios of females to males.

Final decisions as to the lines of social differentiation to be investigated had to be based on the availability of data. The list of twenty-four variables we finally selected, along with their precise definitions, are given in Appendix B.

Three points should be made clear before proceeding with the analysis. First, in comparing the epidemic and nonepidemic areas with respect to the selected social variables, it should be borne in mind that the latter are, in the main, based on the 1950 census, whereas the primary distinction is based on events (incidents of narcotics involvement) that took place between January 1, 1949, and October 31, 1952.2 We are assuming that the state of affairs revealed by the census holds reasonably true for this entire period and for some time prior to it.

Second, by whatever process of thinking we may have come to a variable, the interpretation of a relation between the incidence of cases and that variable is not necessarily limited to that channel of thought. Thus, if we find a greater ratio of females to males in the epidemic than in the nonepidemic areas, it does not necessarily follow that an excess of females in the environment tends to maintain passive orientation or confusion with regard to masculine roles in teen-aged boys. Our initial reasoning, at best, suggests a hypothesis to account for the observed relation. It does not preclude other interpretations or even the possibility that the observed relation may be accidental, in the sense that there is no direct relation. In other words, the excess of females may -have nothing to do with the incidence of drug cases, but be related to another variable which does. The findings should, therefore, be interpreted with caution.

Third, the reader should bear in mind that we are investigating the characteristics of neighborhoods, not those of individual boys. Thus, if we find the anticipated relation of excess of females to incidence of drug use, it does not follow from these data that individual drug-users tend to be surrounded in their intimate circles by a preponderance of females. Nor does a relation between proportion of low-income families and drug use necessarily imply that the drug-users come from the most impoverished families. Nor does it follow, if high-drug-use areas tend to be heavily populated by Negroes, that the Negroes in these areas are more likely to become drug-users than the whites. The variables we are considering are likely to be reflected in, or to be indicators of, the cultural climate and the ethos of the neighborhoods; the degree of vulnerability to drugs is at least partly determined by the cultural climate and the ethos.

An analogy may be helpful. People living in a rat- or vermin-infested environment are more vulnerable to diseases spread by rats or vermin, regardless of their personal habits. In the same way, people living in areas where the dignity of human beings is of little worth are likely to develop corresponding attitudes, even though they may not themselves have experienced direct assaults. People living in areas where they are surrounded by disrupted family life may develop certain attitudes which would not be at all justified by their personal family experiences. Members of discriminated-against minority groups do not have to experience discrimination personally for it to become a major fact in their lives; and members of majority groups in the same areas learn in many ways that such ideals as that of the equality of all men regardless of social position and that of the brotherhood of man are not always taken seriously in practice.

We are trying to get a view of the kind of environment in which the use of narcotics by teen-aged boys spreads. We assume that the factors which most sharply differentiate the epidemic from the nonepidemic areas contribute, directly or indirectly, to the vulnerability of the boys in the epidemic areas, or that these factors are in some way related to aspects of the sociocultural climate which have this effect.

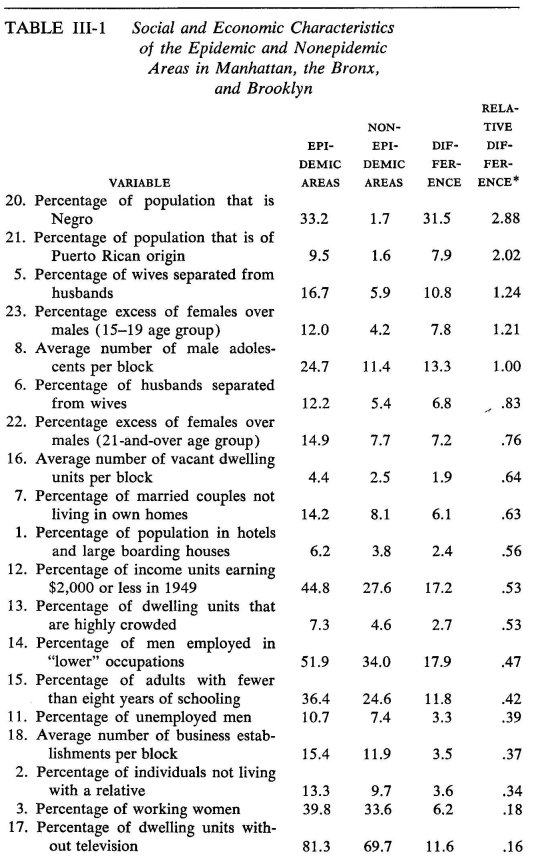

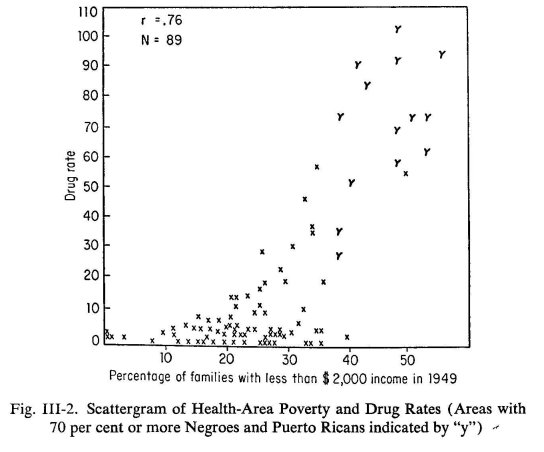

Table III-1 presents, in the order of the magnitude of the relative differences between the epidemic and the nonepidemic areas, the comparative data on twenty-four lines of social differentiation examined. The absolute differences, though of interest in their own right, are not comparable to one another. Thus, the difference of more than 30 per cent in the proportion of Negroes in the two kinds of areas is impressive and, perhaps, tells us a great deal about the difference between the two worlds. This difference, however, cannot be directly compared to the difference of not quite 8 per cent in the proportions of Puerto Ricans. The 1950 census counted 240,730 Puerto Ricans in the three boroughs, in comparison with 690,712 Negroes (exclusive of nonwhite Puerto Ricans). The relatively small total number of Puerto Ricans means that areas of high Puerto Rican concentration must be quite small and these constitute only a fraction of the epidemic areas. If we want to consider the absolute percentages, in this respect, the significant point is to be found in the column for the nonepidemic areas: these have very low concentrations of either Negroes or Puerto Ricans.

In order to provide some degree of comparability of the between-area contrasts provided by the various indexes, we have computed and recorded in the last column of Table III-1 the relative difference between the two areas for each index. This is the absolute difference expressed in terms that are relative to the corresponding index for the three boroughs taken as a unit. Thus, the difference between the epidemic and nonepidemic areas with respect to the average number of male adolescents per block is of the same magnitude as the total three-borough average; the difference with respect to percentages of individuals not living with a relative is about one third as large as the corresponding three-borough percentage; the difference in percentages of wives separated from their husbands is about one-fourth again as large as the over-all percentage; and so on.

Apart from certain purely statistical problems in the interpretation of either the absolute or the relative differences, there is another way in which the information given in Table III-1 can be misleading. We do not know anything about the comparative perceptible impacts of the differences. Consider, for instance, the difference of 17 per cent in the proportions of income units earning $2,000 or less as compared to the difference of 6 per cent in the proportions of working women; in relative terms, the former is almost three times as great as the latter. Yet, for all we know to the contrary, it is conceivable that the latter has much greater consequence in the lives of the youngsters in these areas than does the former.

In general, therefore, the significant fact to be learned from Table III-I is that virtually all of the differences are in the expected direction —expected, that is, on the basis of the reasoning that led us to examine these lines of social differentiation in the first place. In all of these respects, the epidemic areas are "worse off" than the nonepidemic areas.

The two noteworthy exceptions probably have little bearing on this conclusion. The percentages of the populations living at a new address show virtually no difference, and this in the "wrong" direction. We had, however, taken this measure, with some trepidation, as an index of population instability—the proportion of the population that had not been living in the same place long enough to sink roots in the community —and we were interested in population instability only because it might serve as an indicator of the extent of rootlessness in the population. If we had a satisfactory measure of population instability, negative results would not necessarily upset the underlying hypothesis that rootless populations are vulnerable to the spread of narcotics; it is conceivable that stable populations may, for reasons other than geographic mobility, nevertheless fail to develop a sense of rootedness in a community. As is, however, we do not even know how the comparison would have gone had we had the data to compare the relative proportions of people who had been living in the same neighborhoods (rather than at the same addresses) over a longer period than one year.8

As to the second exception—and, if taken seriously, it is a marked contradiction of our expectations—it is not unlikely that it involves a statistical artifact. Establishments employing twelve or more people tend to be concentrated in nonresidential areas. If these happen to be nonepidemic areas, they would markedly raise the index for the nonepidemic areas as a whole; but the index would be quite atypical for the great bulk of the neighborhoods included in the nonepidemic areas.4

Comparisons similar to those given in Table III-1 were made between the epidemic and nonepidemic areas in each of the boroughs. Six of the variables showed reversals in Manhattan with respect to the anticipated direction of the findings. With respect to only one, however, was the difference large enough to suggest that the epidemic areas are markedly "better off," ("better off," that is, in terms of the reasoning that led us to examine the variable in the first place) than the non-epidemic areas, there being, on the average, more than twice as many business establishments per block in the latter areas as in the former. The next largest difference favoring the epidemic areas, of almost 5 per cent, was found with respect to individuals not living with a relative. The third largest reversed difference, of almost 3 per cent, occurred with respect to the number of individuals who had changed their place of residence in the preceding year. There was, on the average, one extra vacant dwelling unit per block in the nonepidemic areas of Manhattan as compared to the epidemic areas.

There was only one reversal in the Bronx and only one in Brooklyn. In both cases, the same variable was involved, with one extra local employee per resident in the nonepidemic areas of the Bronx and almost two in Brooklyn.

Eliminating all variables that did not support the initial reasoning in the over-all comparison or in any of the boroughs and eliminating, in addition, any variable with respect to which the epidemic areas of at least one of the boroughs was not more badly off than the combined nonepidemic areas of the three boroughs" leaves us with the following variables that consistently distinguish the epidemic areas:

20. Percentage of population that is Negro

21. Percentage of population that is of Puerto Rican origin

5. Percentage of wives separated from husbands

8. Average number of male adolescents per block

6. Percentage of husbands separated from wives

22. Percentage excess of adult females over males

7. Percentage of married couples not living in own homes

12. Percentage of income units earning less than $2,000 in 1949

13. Percentage of dwelling units that are highly crowded

14. Percentage of men employed in "lower" occupations

15. Percentage of adults with fewer than eight years of schooling

11. Percentage of unemployed men

3. Percentage of working women

17. Percentage of dwelling units without television

The epidemic areas are, on the average, areas of relatively concentrated settlement of underprivileged minority groups, of poverty and low economic status, of low educational attainment, of disrupted family life, of disproportionately large numbers of adult females as compared to males, and of highly crowded housing; they are densely populated and teeming with teen-agers.

It is not true, of course, that the epidemic areas are homogeneous in these respects, and we shall return to the question of differentiation within these areas. Of more immediate relevance is the reminder that it cannot be asserted that the differences we have found between the epidemic and nonepidemic areas are, individually or collectively, directly responsible for the use of narcotics by teen-aged boys. All that we can say is that we have depicted a situation that constitutes a fertile soil for this kind of deviant behavior.

Two other reminders should perhaps be added. In the first place, we have, after all, studied drug use only in New York City and have considered only three of the boroughs, at that. In general, however, the image that has emerged is consistent with the impressions of those who have worked with juvenile drug-users in other cities. In the second place, poverty, heavy concentrations of underprivileged minority-group populations, and so on are, of course, not unknown outside the large metropolitan areas; but, as far as is known, drug use by young people (and by older ones as well, for that matter) is essentially a metropolitan phenomenon.

Suppose that the image we have drawn of the epidemic areas could be duplicated point for point; would the existence of similar conditions elsewhere, without extensive drug use, imply that our findings were causally irrelevant? Not at all. It takes more than fertile soil to grow a crop; one needs seed as well. In the case of narcotics, one needs access; and there are many reasons why access should be, by far, easiest in large cities. Organized crime, of which illegal traffic in narcotics is but one aspect, is itself a phenomenon of large cities. Until a sufficiently large corps of salesmen can be built up out of entrapped addicts, the basic personnel of the business must be drawn from otherwise criminal elements of the population, and these would be conspicuous if they invaded areas radically different from their normal habitats. Moreover, insofar as the bribery and connivance of some law enforcement officers is a necessary condition of the maintenance of the traffic, the problems of making the right contacts must be enormously complicated as the number of independent law enforcement agencies involved increases. In addition, the illegal traffic in narcotics confronts many difficulties as is and hence has especially much to gain from a potentially concentrated market; it does not, so to speak, need the extra headaches of a dispersed market.

Drug Use and Juvenile Delinquency

A glance at the map of the distribution of drug-involved cases and at a similar map of juvenile delinquency prepared by the New York City Youth Board suggests a close relationship between the distribution of juvenile delinquency and that of narcotics violations. The latter are, of course, per se illegal, so that they contribute to the distribution of the former. How do the two distributions compare when the two sets of violations are separated? Are these independent forms of pathology, or do they tend to breed on the same ground? In other words, is the phenomenon that we are trying to explain one of generalized lawlessness, of which drug use is only one aspect, or is drug use a special kind of lawlessness with a quite different kind of causation?

To answer this question, we examined the charges entered in the docket books of two courts dealing with young male offenders in Manhattan—Youth Term and Felony courts. The study was limited to Manhattan, mainly for practical reasons, and only males in the sixteen-to-twenty age range were included5 in order to maintain comparability with the drug study.

Again mainly for practical reasons, docket charges were used rather than final case dispositions. We believe, however, that the docket entry reflects the nature of the delinquent act at least as accurately, and probably more so, as the final disposition, in which the charge is often reduced or changed to the nondescript "wayward minor" The possibility of unjustified charges in the one case is counterbalanced by the possibility that justified charges may not be backed up by sufficient legal evidence in the other. We have no way of evaluating the relative weight of the two types of error.

No attempt was made to eliminate case duplications—i.e., instances in which the same case is brought to court more than once—since we are primarily interested in the number and variety of delinquent acts discovered and brought to court from various neighborhoods.

There were 10,025 delinquency charges of all kinds in our age group in the two Manhattan courts from January 1, 1949, to December 31, 1952. Within each court and for each year separately, we took a 23 per-cent random sample of the docket charges on the basis of a table of random numbers. All charges involving narcotics violations, females, and individuals with addresses outside the borough were eliminated. This left us with 1,514 charges against males in the sixteen-to-twenty age range and involving other-than-narcotics violations. The addresses of the alleged offenders were classified on a health-area basis, and health-area delinquency rates were computed. These were compared to the corresponding health-area drug rates.

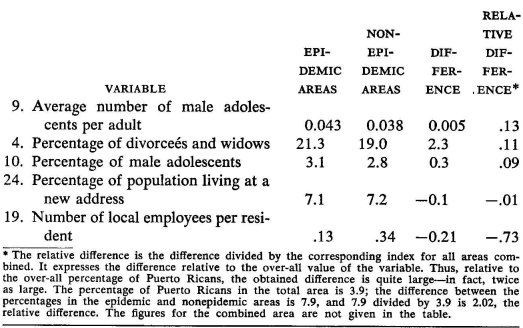

If one plots drug rate against delinquency rate on a graph, there is a clear trend (see Figure III-1): the drug rate tends to increase with the delinquency rate. Expressed differently, health areas with higher delinquency rates have, on the average, higher drug rates. The degree of relationship between the two rates may be expressed by a moderately high correlation coefficient of .63. The true relationship, however, is more complex than would be evident from this statement. There are actually two kinds of high-delinquency health areas; some are quite high in drug rate, and some relatively low. Thus, among the twenty-nine health areas with delinquency indexes of 40b or more, seven have drug rates of less than 10, and another six of less than 20. Then there is a large gap. Another two of this group of health areas fall in the drug-rate class of from 38 to 40, and the remaining fourteen run from drug rates of over 50 to over 100. By contrast, none of the health areas with delinquency rates of less than 40 have drug rates of 50 or more; two (with delinquency rates over 30) have drug rates of 38 and 48, respectively; seven (all with delinquency rates over 15, and five of them over 20) have drug rates ranging from 20 to 33; five (also all with delinquency rates over 15) have drug rates of from 10 to 20; and forty-seven (running the gamut of delinquency rates from zero to 40) have drug rates of less than 10.

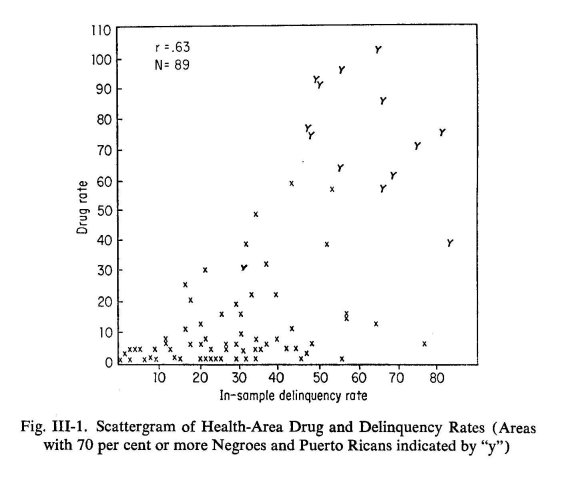

Of the fourteen health areas with drug rates over 40, twelve have populations of 70 per cent or more Negroes and Puerto Ricans. There are only two other health areas in Manhattan which are so heavily segregated with respect to these minority groups. One of these, with the highest delinquency rate in the borough, has a drug rate of 38; the other has drug and delinquency rates of about 30. The highly segregated health areas are, however, distinguished by more than segregation, high delinquency rates, and high incidence of juvenile drug involvement. Only two less-segregated health areas have as many families with 1949 incomes of less than $2,000; from almost 40 to almost 60 per cent of the families in the highly segregated areas have such incomes (See Figure 111-2). One of the less-segregated areas in this income group has a drug rate of 57, but the other has one of less than 5. The remaining two areas with drug rates over 40 have more than 30 per cent of their families in this low-income bracket. The health-area correlation between drug rate and percentage of families with 1949 incomes under $2,000 is .76.e The health-area correlation between delinquency rate and poverty index is less: .68.

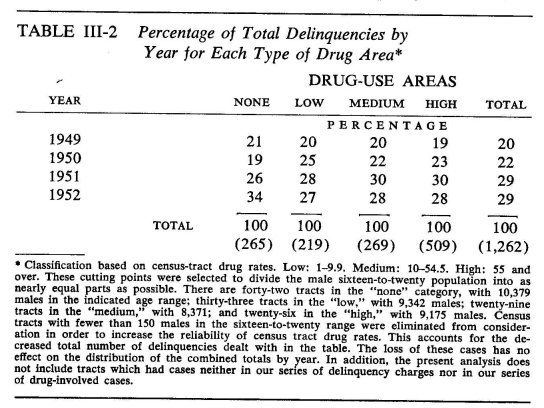

The high correlation between drug use and delinquency fits well with a stereotype of narcotics as a cause of crime. The years 1949-1952 saw a marked increase in juvenile drug use; they were also years of increasing delinquency. The year 1949 contributed 20 per cent of the delinquencies in our sample; 1950 contributed 22 per cent; and 1951 and 1952 each contributed 29 per cent. The simultaneous increase of the two types of violations is consistent with the stereotype. There are, however, facts which sharply contradict it.

In the first place, the increase was at the level of minor violations. The number of felonies remained virtually constant over this four-year period. At the very least, then, there is no support here for the notion of the most serious crimes being associated with the taking of drugs,6 at least among the males under twenty-one. The virtual constancy in the number of felonies also raises a serious question about the nature of the "crime wave." The period was one in which there was not merely an increase in delinquency charges, but one in which many voices were being raised about the "alarming" increase in juvenile delinquency. The constancy of the incidence of felonies, however, gives one pause. The distinction between a felony and a misdemeanor may be a relatively sharp one in legal terms; it cannot be so in behavioral terms. Consequently, if there had been a real increase in misdemeanors, one would expect, although perhaps not in constant ratio, increases all along the behavioral gradient of severity of offense, and, hence, one would also expect an increase in number of felonies. The fact that such an increase does not occur suggests that the "crime wave" is most plausibly interpreted in terms of police activity. Specifically, if there were no real increase at all, but if cases were more readily brought to court for offenses which would have formerly been ignored or dismissed by the police officer with a warning, we would get exactly the kind of curves we do get.

In the second place, if the use of narcotics is a major cause of other types of crime, one would expect the most marked changes in the high-drug-use areas. That this is not the case may be seen from Table III-2.

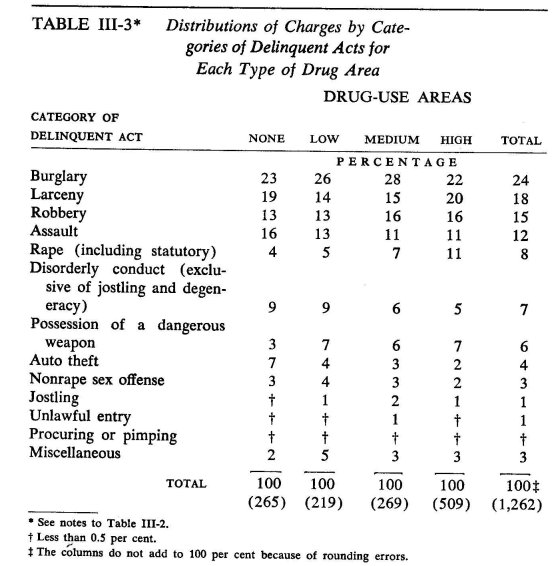

In the third place, our data suggest that, though drug use has no marked effect on the relative incidence of delinquency (exclusive, of course, of the narcotics violations), it does affect the type of delinquency committed; it tends to be associated with a larger proportion of utilitarian violations than crimes of violence or other behavior disturbance. This ffies directly in the face of the stereotype.

The relative distributions of the various types of charges are given in Table III-3. It may be noted that relatively—i.e., in comparison to the "no"- and "low"-drug-use areas—small proportions of the charges in the "medium"- and "high"-drug-use areas involve assault, disorderly conduct, or auto theft. Relatively high proportions involve robbery or rape. The other categories do not show any clear trends.

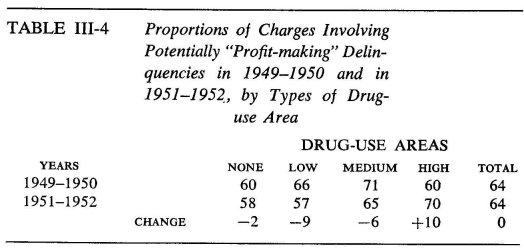

In order to get a clearer picture of what is happening in the various types of area, the delinquent acts were further classified into two inclusive categories: (1) potentially profit-yielding and (2) others. The following groups of charges were classified as potentially profit-yielding: robbery, jostling (attempted pickpocketing), procuring or pimping, unlawful entry, burglary, larceny.

Possession of a dangerous weapon was not included in either category since, according to officials in the Probation Department, about equal numbers of charges of this type come from roundups of delinquent gangs engaged in or preparing for street warfare and from boys who probably possessed these weapons for purposes of robbery. The exclusion of this category from the following analysis, if anything, militates against the point we are about to make; as we shall see in a later chapter, drug-using gangs tend to cut out street warfare.

Similarly, the assignment of rape to the second category probably also militates against the point we are about to make. In the highdrug-use areas, many statutory rape charges are probably an indirect consequence of the "fund-raising" activity that is a necessary condition of much drug use. The adolescent female drug-user characteristically obtains money for drugs by means of prostitution, and it is not unreasonable to expect a large number of rape charges in neighborhoods with many prostitutes who are legally minors. When these girls are arrested, they are often persuaded to reveal the identities of their clients, who automatically become subject to charges of statutory rape.

At any rate, whatever may be said of the crudeness of the procedure, the result of the analysis is interesting. This result is given in Table III-4. There was no over-all change from the two-year period 1949— 1950 to the two-year period 1951-1952 in the proportion of charges involving potentially "profit-making" delinquent acts, and there was very little change—a decrease—in the "no"-drug-use area. The "low"-and "medium"-drug-use areas, however, showed marked decreases in this respect; but the high-drug-use area showed a marked increase. In other words, whereas the delinquents in other areas showed an increased inclination to turn to what might be described as behavior-disturbance types of delinquency, the delinquents in the high-drug-use area showed an increased concentration on potentially money-making delinquencies.

To be sure, there is no assurance that such crimes as robbery may not be primarily crimes of aggression, with relatively little interest in the financial return. We have only examined gross statistics, not individual motivation, and we do not know from these data the distribution of the motivations toward delinquent acts. Still, the findings make sense. Heroin is a tranquilizer—perhaps the most effective tranquilizer known—but it comes in expensive doses.

We began this section with a question about the nature of the phenomenon we seek to explain. Is drug use simply another expression of lawlessness? Is the distribution of drug use simply a manifestation of the general distribution of lawlessness, and is the explanation of the distribution of drug use to be found in the explanation of the distribution of lawlessness? It turns out that the two do tend to go together, but not always. There are areas of high delinquency with relatively little drug use—hardly an astounding finding, since we did have delinquency before drug use, but it does indicate that high-delinquency areas can remain resistant to drug use when the latter does arrive on the scene.

Which high-delinquency areas succumb most readily? We have explored only two dimensions of differentiation. The high-delinquency areas most vulnerable to the spread of drug use are the ones that are most heavily populated by the two most deprived and discriminated-against minority groups in the city, and they are the areas with the highest poverty rates. If we had explored other lines of differentiation, the differences between the two kinds of high-delinquency areas would undoubtedly parallel the other differences we have already found between the epidemic and nonepidemic areas; these dimensions are not independent, but highly correlated. In other words, the high-delinquency areas that are most vulnerable are the ones that are "worst off" in a variety of respects.

On the other hand, the highest-drug-rate areas are all high-delinquency areas. Is delinquency in these areas a consequence of drug use? The evidence is that it is not, except in the sense that the varieties of delinquency tend to change to those most functional for drug use; the total amount of delinquency is independent of the drug use.

Socioeconomic Correlates of Drug Use in the "Epidemic" Areas

The comparison of epidemic and nonepidemic areas has given us a picture of the kind of social world in which the use of narcotics by older boys and young men thrives. The question now before us is whether we can disentangle among the social differentiae of the two worlds those most relevant to the spread of this type of deviant behavior.

Do poverty and squalor establish a hopelessness from which one can seek refuge only in the serenity of a chemically induced state of nirvana?' Does the widespread disruption of family life induce or sustain the sense of aloneness in the individual from which he seeks escape in a drug-induced illusion of oneness with the universe? Is the turning to narcotics a desperate effort of "emasculated" males in a world inundated by females to assert their independence? Is the hospitality of the social climate to drug use simply an exaggeration of normal teenage conformity and an exacerbation of normal tendencies of adolescent boys to mutually induced states of social intoxication in which they undertake deeds of reckless derring-do and rash bravado—grim realizations of the potentials of teen-age coexistence, generated by excessive numbers of teen-agers in close proximity to one another? Is it some combination of factors, say, a breakdown of adult authority confronted by adolescent rebelliousness, as evidenced by the major significance of excessive numbers of teen-agers in a world of disrupted family life?

To be sure, these questions may be fancifully put in the light of the kind of evidence that we can marshal. There is, for example, quite a gap between a prosaic "percentage of income units earning less than $2,000" and related variables, on the one hand, and "a hopelessness from which one can seek refuge only in the serenity of a chemically induced state of nirvana," on the other. Yet, if it were to turn out that these are the only variables of major significance, such an interpretation may not be far-fetched. Similarly, other possible outcomes of the analysis might suggest the interpretation implicit in one or another of the questions. Still other outcomes may tell a story not anticipated by any of the questions; they were not intended to be more than an illustrative listing of possibilities.

How, then, disentangle the roles of the variables? To begin, it seems reasonable to suppose that the place to study these roles is where drug use occurs. That is, we are concerned with the islands designated as epidemic areas and the immediately adjacent census tracts. Within these regions, there is considerable variation in census-tract drug rates, despite the fact that there are drug markets available to all. Or, to pursue a different analogy, all are reasonably close to the sources of infection; if there is nevertheless variation in the intensity of contamination, this variation is likely to be directly related to differences in vulnerability. The further we get from these critical areas, the less certain we can be that the absence of signs of contamination may not be due simply to distance from the centers of contagion rather than to resistance.

In the second place, a well-developed technique for studying the roles of variables in relation to a selected one involves correlational analysis. The result of the application of this technique is not unequivocal; the correlation coefficient is itself ambiguous from the viewpoint of causality,8 and hence any results based on the examination of correlation coefficients must also be ambiguous.

In principle, the only way of studying causal relationships without ambiguity is by direct experimentation. Applied to the present case, this would call for the following: Census tracts in which there is no drug use would be divided into homogeneous groups (i.e., the census tracts in each group would be selected so that each tract in the group resembles every other one with respect to what are assumed to be the relevant significant variables). From each group, we would randomly select one or more tracts for experimental treatment and one or more tracts for purposes of control. The experiment would consist of trying to seduce the youth of these tracts into drug use. How much could be learned from such an experiment would depend on further details of the experimental design, but, needless to say, not even the most primitive experiment calling for such measures could be carried out. Even if one could find trained personnel willing to try, the social and, hence, the behavioral meaning of drug use would necessarily change so that we would be studying a quite different phenomenon from the one which concerns us—the illicit and heavily prosecuted use of narcotics.

The most that we can hope for, therefore, is that, once the basic correlational facts are clear, they will lend themselves to sensible interpretation. If the interpretations turn out to be debatable, they (and whatever alternatives may be suggested) will nevertheless be based on a foundation of sounder information than guesses based on no information at all.

One statistical point should be explained before we proceed with the analysis—the relation between the correlation coefficient and the variances of the variables involved. Variance is one of a large number of measures of the variability of scores in a distribution.d It can be shown that the square of the correlation coefficient gives the proportion of the variance of one variable that can be statistically accounted for in terms of the other.°

To illustrate this point concretely: The correlation between drug rate and the percentage of Negroes is .77 in the Manhattan epidemic and border areas. On the basis of this relationship, we can calculate the drug rate that would be expected from the over-all trend for the particular percentage of Negroes in a given census tract in the designated area. This gives us one component of the drug rate, a component that can be "accounted for" by the percentage of Negroes in the tract and the known correlation between drug rate and percentage of Negroes. If we subtract this "expected" drug rate from the actual drug rate (and, since the "expected" rate may be larger or smaller than the actual rate, this may leave us with either a positive or negative number), we are left with a second component of drug rate, one that cannot be "accounted" for on the same basis. The words "accounted" and "expected" have been surrounded by quotation marks to emphasize that the accounting and expectation involved are on a statistical and not necessarily a causal basis. If we were to compute the "expected" drug rates for each of the tracts, the variance of the "expected" components would turn out to be 59 per cent (.77 squared times 100) of the variance of the actual drug rates, and, in this sense, we would have accounted for 59 per cent of the variance of the drug rates. The variance of the left-over components would turn out to be 41 per cent of the variance of the actual drug rates. Stated differently, if we were to hold the percentage of Negroes statistically constant, the variance of the drug rates would go down to 41 per cent of their original variance.

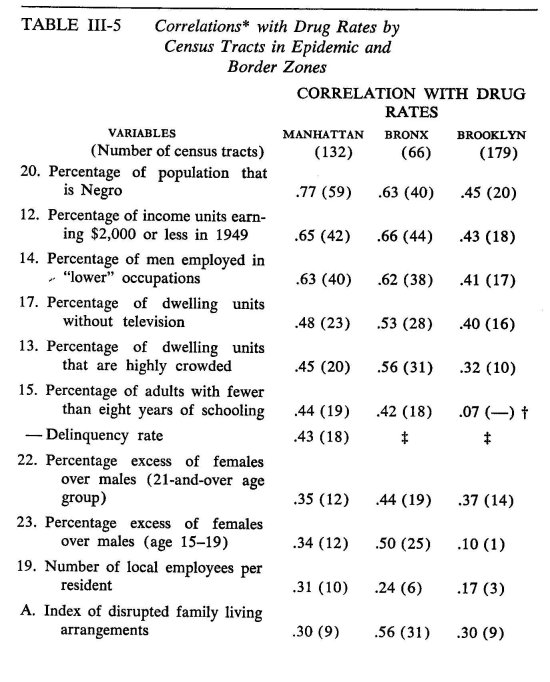

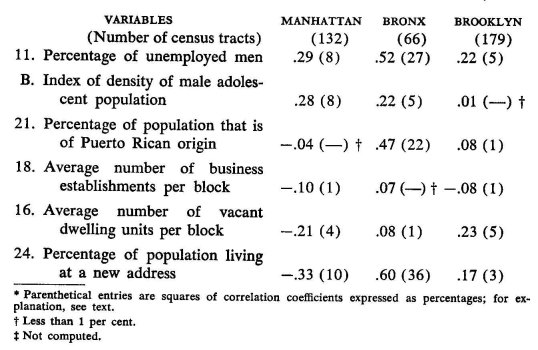

The correlations between each of the variables that we investigated and the drug rate are given in Table The correlations were calculated separately for each of the boroughs and, as previously explained, are based on only the census tracts in the epidemic areas and those immediately adjacent to them. g Alongside each coefficient, in parentheses, is given the percentage of the drug-rate variance that can be "accounted for" by that variable.

The three variables that stand out most in all three boroughs in terms of their respective abilities to account for the variance in drug rates are percentage of Negroes, percentage of low-income units, and percentage of males in "lower" occupations. No particular significance should be attached to the fact that the correlations in Brooklyn are considerably lower than those in Manhattan and the Bronx. The variance in drug rates in Brooklyn is considerably smaller than the variances in the other two boroughs (about two-thirds of that in Manhattan and four-fifths of that in the Bronx), and accounting for a small portion of a small variance is, in an absolute sense, not necessarily a poorer accounting job than accounting for a larger part of a larger variance. Over a comparable range of drug rates, the discrepancies between drug rates and, say, percentage of Negroes may be of the same order in the two cases.

To put the same point differently, relative to the degree of dispersion of scores (and this is what counts in computing the correlation coefficient), a small absolute difference between two scores may loom large if the variance is small and be quite trivial if the variance is large.' For this reason, we are mainly interested in the order of the relationships. On this basis, the three variables mentioned at the beginning of the preceding paragraph are most closely related to drug rates in each of the three boroughs.

In the case of some of the variables, the correlations with drug rates are quite different, even in ordinal terms, in the three boroughs. The most extreme case involves the percentage of people living at a new address; this variable yields the fourth highest positive correlation in the Bronx, but the most marked negative correlation in Manhattan. We have already noted that this variable cannot be interpreted as we had originally hoped; that is, we cannot take it as a satisfactory measure of possible rootlessness. Its quite different behavior in the three boroughs in relation to drug rate is also associated with markedly different patterns of recent residential change. In the Bronx, most of the moving has been into census tracts of high unemployment, low occupations, disrupted family life, relatively high concentrations of Puerto Ricans, and low incomes; the correlations with these variables are, respectively, .74, .71, .68, .65, and .62. In Manhattan, the trends 'fire less marked, but, such as they are, the tendency has been for moving into areas of higher occupations, higher educational levels, lower density of male adolescent population, and fewer Negroes; the correlations are, respectively, —.46, —.41, —.40, and —.37. In Brooklyn, the pattern is again different, but, in character, more like that in the Bronx. The highest correlations are with percentage of families without television (.44), percentage of Negroes (.42), crowded dwelling units (.41), disrupted families (.41), vacant dwelling units (.40), and low incomes (.39). Clearly, this variable has no consistent meaning, so that its varying behavior with respect to drug rate is not remarkable.'

In general, the varying behavior of the mobility variable with respect to drug rates in the three boroughs is related to the differing relationships among the variables themselves. The second most noteworthy case of a variable with markedly varying relationships to drug rate—percentage of Puerto Ricans—merits some special comment. If drug rates are plotted against this variable, the line which best marks the trend turns out to be far from straight; it is, in fact, a markedly U-shaped curve. That is, drug rates are highest in the tracts where the percentages of Puerto Ricans are relatively low and also where they are relatively high; they are lowest for intermediate ranges of percentages of Puerto Ricans. If one were to add the excluded tracts without any Puerto Ricans, the curve would be even more remarkable, for all the tracts excluded from the analysis have zero or nearly zero drug rates.

In other words, the full curve would tell the following story. There is no known drug use among teen-aged boys where there are no Puerto Ricans. But, as we move into tracts with low concentrations of Puerto Ricans, drug use jumps to very high levels. As we go on to tracts with higher concentrations of Puerto Ricans, drug rates fall markedly. But, as we continue into tracts with still higher concentrations of Puerto Ricans, the drug rates again mount to very high levels.

The key to the puzzle is that, in the epidemic areas, census tracts with high concentrations of Negroes—a state of affairs that almost necessarily implies low concentrations of Puerto Ricans—have high drug rates. But, as we move into tracts with relatively low concentrations of Negroes, there is an almost linear increase in drug rate with increasing concentrations of Puerto Ricans. If we had had the foresight to define the Puerto Rican variable in terms of the percentage of Puerto Ricans in the non-Negro population, the relationship of this variable to drug rate would undoubtedly have been not greatly different from that obtained for percentage of Negroes. The wisdom of hindsight is assuredly impressive, but it still leaves us with a virtually useless variable for the purposes of the remaining analysis of these data. Suffice it to say that it is ,hardly likely that the condition of being of Puerto Rican origin is per se conducive to the use of narcotics by teen-aged boys. The true story of the segregated Puerto Rican neighborhoods in relation to juvenile drug use is doubtless not very different, except perhaps in minor details, from the story of the segregated Negro neighborhoods.

It may be noted that, for all of the differential behavior of some of the variables in relation to drug rate in the three boroughs, the general order of the relationships is fairly consistent from borough to borough. The rank-difference correlation° between the correlation coefficients of the sixteen variables is .60 for Manhattan and the Bronx, .72 for Manhattan and Brooklyn, and .75 for the Bronx and Brooklyn; if the four most "misbehaving" variables (i.e., the ones yielding the most variable correlations with drug rate) are eliminated, these become, respectively, .83, .92, and .93. The variables are listed in Table III-5 in the order of the magnitude of the correlations with drug rate in Manhattan, the borough with, by far, the greatest drug problem. Except for a minor inversion involving first and second place in the Bronx, the first six variables in the list are in the identical order in the other two boroughs. The major story that they have to tell is that the incidence of drug use among teen-aged boys is one of segregated slum areas.

If one were to add the percentages of accountable drug rate variance in any of the columns of Table III-5, it is obvious that they would add up to considerably more than 100 per cent. The reason for this is not difficult to find. These variables are correlated with one another as well as with drug rate. Consequently, the portion of drug-rate variance that can be accounted for by one of them overlaps with the portion that can be accounted for by another. By certain advanced techniques of correlational analysis, it is possible to straighten out the picture of the collective relationship. Thus, by means of what is called multiple-correlation anaylsis, it is possible to eliminate the duplication in the accounts)

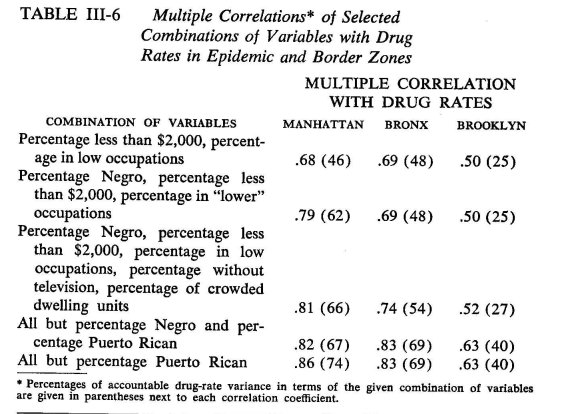

Table III-6 gives the multiple correlations of selected combinations' of variables with drug rate, along with percentages of accountable drug-rate variances. The Puerto Rican variable was not included in any of the combinations because of the already noted deceptive character of the correlation coefficients involved.

As might be expected, combinations of variables do a better job of accounting for the drug-rate variances than do the individual variables. Even so, substantial portions are not accounted for, most notably so in Brooklyn. It does not follow, however, that the addition of other variables to the set would markedly improve the picture. We have already noted that there are undoubtedly errors of measurement in these data. Insofar as there are such errors in the drug rates, this would account for a portion of the drug-rate variance; and, where the absolute drug-rate variance is small, as in Brooklyn, even small errors would loom relatively large) k Insofar as there are errors in the other variables (e.g., related to errors of enumeration in the census), they cannot be expected to do a perfect accounting job. In the light of these considerations (and the restrictions on the correlations due to the excluded census tracts), the proportions of accounted-for drug-rate variance are well above our initial expectations.

A second point to be noted in Table III-6 is that the percentage of Negroes adds nothing to the accounting of the drug-rate variance given by percentage of low incomes and percentage of males in "lower" occupations in the Bronx and Brooklyn. If it still accounts for 16 per cent more of the variance in Manhattan than do the latter two variables jointly, this special contribution of percentage of Negroes to the accounting has shrunk to less than half of that amount by the time we introduce the other variables into the accounting system. This still leaves us with 7 per cent of the Manhattan drug-rate variance associated with degree of Negro segregation that is not otherwise accounted for by any of the other variables that we have considered.

What is special about the Negro slum areas of Manhattan that makes their teen-aged boys vulnerable to the lure of narcotics, we do not know. That it is not the sheer fact of Negro population seems obvious in the light of the Bronx and Brooklyn findings. It is possible that the cumulative impact of many unwholesome conditions produces a surplus of vulnerability beyond the net sum of the impacts of the individual conditions. We have not, however, provided for the testing of such a possibility in our system of accounts.'

Finally, it may be noted that two variables, percentage of low incomes and percentage of men in "lower" occupations, account for 62 per cent of the portion of the drug-rate variance in Manhattan that can be accounted for by the entire set of variables, 70 per cent in the Bronx, and 63 per cent in Brooklyn. When percentage of Negroes is added, this figure shoots up to 84 per cent in Manhattan, but remains unchanged in the Bronx and in Brooklyn. When percentage of families without television and percentage of crowded dwelling units are added to the preceding trio of variables, the corresponding figures become 89, 78, and 68 per cent. Although not included in Table III-6, if the last of the economic variables we have examined—percentage of unemployed males—is added to the set, the figures become 93 per cent, 80 per cent, and the last remains the same.

As far as the social environment is concerned, the vulnerability of teen-aged males in New York City to the lure of narcotics is in the main associated in some fashion with living in areas of economic squalor, but other unwholesome aspects of the social environment also contribute in substantial measure. That is, conditions of economic squalor dominate the picture, but virtually the entire complex of unwholesome factors plays a contributory role. We had hoped, but not really expected, to discover one or two clear-cut factors that could account for the lure of narcotics; but, as usual, social causation is a complex affair.

STATISTICAL FOOTNOTES

a Actually, only one variable was eliminated solely on the latter basis: the epidemic areas of Brooklyn showed an excess of 6.3 per cent in number of adolescent girls as compared to an excess of 7.7 per cent for the combined nonepidemic areas. The nonepidemic areas of Manhattan showed an excess of 9.0 per cent, less than did the epidemic areas (16.1 per cent), but almost as high as the epidemic areas of the Bronx (11.2 per cent) and higher than the epidemic areas of Brooklyn. Within each borough, the difference was in the expected direction.

b The delinquency rates are based on the sample. Since the sample includes only 23 per cent of the charges, they should be multiplied by 4.3 to give an estimate of the actual total number of charges per 1,000 boys. The numbers are, in any event, not directly comparable to the drug rates; the latter concern persons, the former, acts.

c Even this high correlation underestimates the relationship. It describes a linear trend, whereas the actual trend is clearly curvilinear. For the health areas with fewer than a fourth of their families in the indicated plight, there is a slowly increasing drug rate as one ascends the poverty scale; for the health areas with from about 25 to 40 per cent of their families in this plight, there is a very rapid climb in drug rate; beyond the 40 per-cent point, the rate of increase in drug rate decreases markedly.

d To the nonstatistician, one of the most obvious ones is the average deviation; that is, for each score, we calculate how much it differs from the mean of the distribution, and then we average the differences. The more scores differ from one another, the greater the value of the average deviation. In calculating the variance, we average the squared deviations from the mean; that is, for each score we calculate how much it differs from the mean. Then, instead of proceeding as for the average deviation, we square each of the differences and average the squares. The square root of the variance is known as the standard deviation. A major advantage to the use of variances rather than other measures of variability is that variances can be analytically subdivided. Specifically, if the scores are subdivided into a number of independent components, then the variance of the whole scores equals the sums of the variances of the components. One of the many applications of this principle is dealt with in the text.

eIt is sometimes stated that the use of the correlation coefficient presupposes that both variables are normally distributed (i.e., that they have a distribution which is sometimes referred to as "bell-shaped"; see Appendix C, Note f). Though true of some applications, this assumption is not involved in either the derivation of the formula for the correlation coefficient or in the relationship described above.

f In the same way, the drug rates "account for" 59 per cent of the variance of percentage of Negroes and leave 41 per cent of the variances "unaccounted for." In this case, the accounting is quite obviously not causal.

g These correlation coefficients are, in most cases, lower than they would have been if all the tracts were included, particularly so in relation to the variables at the top of the list in Table III-1. This follows from the facts that all of the tracts that were not included have zero (or very close to zero) drug rates and that they tend to differ markedly and in the "right" direction from the epidemic-area tracts with respect to the second variable involved in a particular correlation.

h The issue is, of course, further complicated by the variance of the second set of scores involved in a correlation. These are generally smallest in the Bronx and greatest in Manhattan.

1 The different patterns of correlation of change of address provide a clue as to why this variable has a quite different meaning in the three boroughs. The patterns are consistent with certain commonly recognized population-mobility trends. Better-off families with children commonly move into the suburbs and newer city residential areas—mostly in Queens and to some extent in Brooklyn—making way for relatively worse-off families. This migration trend is apparently most marked in the Bronx. On the other hand, suburbanites whose children are grown commonly move back into the newer and more expensive city apartments —mainly in Manhattan. What we really need are age-group-specific mobility rates.

To illustrate with a simple case, consider drug rate in relation to only two other variables, say, percentage of Negroes and percentage of low incomes. We first split drug rate into two components, one which can be "accounted for" in terms of percentage of Negroes and a second which is unrelated to the latter. We similarly split percentage of low incomes into two components, one related to percentage of Negroes and a second unrelated to the latter. We then split the second component of drug rate into two components, one related to the second component of percentage of low incomes and a second unrelated to the latter. We have thus split drug rates into three components: a component which can be "accounted for" by the percentage of Negroes, a component which can be "accounted for" by the component of percentage of low incomes which is unrelated to percentage of Negroes, and a component which is unrelated to either percentage of Negroes or percentage of low incomes. We can compute the variance of each of these components, and the sum of these three variances will equal the total variance in drug rate. The proportion of the total drug-rate variance contributed by the first component plus the proportion contributed by the second equals the square of the coefficient of multiple correlation; or, equivalently, the coefficient of multiple correlation is the square root of 1 minus the proportion of the total variance contributed by the third component. Alternatively, we could, with the same result, split drug rate into the following three components: one related to the percentage of low incomes, one related to the component of percentage of Negroes which is unrelated to percentage of low incomes, and a third which is unrelated either to percentage of Negroes or to percentage of low, incomes. If we were now to add still another variable to the set, we would first derive a component of the latter which is unrelated either to percentage of Negroes or percentage of low incomes and split the third component of drug rate into one which is related and one which is unrelated to the derived component of the last variable, and so on as we add still other variables. The coefficient of multiple correlation is always the square root of 1 minus the proportion of the total drug-rate variance contributed by the component of drug rate that is unrelated to any of the other variables under consideration. The actual computation of the coefficient of multiple correlation abbreviates the procedure just described, but even so one cannot go on adding variables without rather quickly running into the need for electronic computers.

k The point is that one may think of error as a component of a score. On this basis, the earlier representation of the decomposition of drug rates into a number of components was oversimplified. A closer approximation to a correct description would be as follows. The true component of any given obtained drug rate is decomposed into components that can be accounted for on the basis of the other variables and a component that cannot be so accounted for. The total variance of the obtained drug rates equals the sum of the variances of these components plus the variance of the error component. Insofar as the absolute errors in drug rates are of comparable magnitude in the three boroughs, the variances of the error components would also be approximately equal; but, if the total variance of the drug rate is smaller in one borough than in the others, the proportion of the total variance taken up by the error variance must be larger in the first instance than in the others.

It is to be noted that the errors we are discussing are real errors, rather than conceptual constructs, such as are involved in some discussions of psychological test scores, where the "true" score is conceived of as the average of the test scores obtained by a person in an infinite number of replications of testing under identical conditions. Also to be noted is the assumption that the errors of measurement are randomly distributed, an assumption that is reasonable in the light of the arguments and evidence we have adduced for taking the obtained distribution of drug rates seriously.

A simple score based on the number of unwholesome conditions (an "unwholesome condition" being defined as, say, being in the top quarter or third of the census tracts with respect to a given variable) would have helped to clarify the issue if added to the set of variables. This, however, is also a matter of hindsight, although we had used such a variable in a preliminary analysis of the data. Unfortunately, this analysis is not in a form that can be brought to bear here. It is our impression that the Negro slums of Manhattan are worse off in this respect than those in the Bronx and Brooklyn.

1 R. K. Merton, "Social Structure and Anomie: Continuities," in Social Theory and Social Structure (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1957).

2 Because of the availability of the data on a census-tract basis, the greater reliability of the early-period drug rates and the fact that the additional data drawn from the census become increasingly inaccurate as we go further from the base year of the census (1950), we have restricted the analysis in this chapter to the early period.

3 We shall be able to throw some additional light, below, on what went "wrong" with this variable as measured.

4 This objection to the index is not relevant to the primary purpose for which we intended it and to which we shall return—the comparison of individual census tracts.

5 The coverage is incomplete with regard to twenty-year olds. Those charged with misdemeanors or summary offenses are mostly brought to trial in district courts. Our data therefore include the felonies committed by this age group, but do not include most of the lesser charges. It should also be noted that studies of juvenile delinquency are commonly concerned with offenses by individuals up to the age of sixteen. The Youth Board maps referred to above, of course, include this age group; they also include an indeterminate number of behavior disturbances that do not involve violations. The Police Department is regarded by some parents as a quasitherapeutic agency; cases referred on this basis come to the Juvenile Aid Bureau of the Police Department and, thence, to the Youth Board statistics.

6. It should be recalled that direct violations of narcotics laws have been systematically excluded from the series of delinquency charges. This does not, however, exclude the possibility of crimes carried out for the sake of obtaining drugs, crimes committed in the course of the withdrawal syndrome, or crimes committed in sufficiently mild states of narcotic intoxication. In other words, the finding and the corresponding inference are not artifacts of the procedure.

7 "Nirvana" is a concept in Hindu and Buddhist philosophy that designates fulfillment of all desire through the conquest of desire. The term has come into common use in contemporary psychological literature in a somewhat broadened meaning. The term "conquest" implies the exercise of discipline; in psychological usage, the sense of fulfillment associated with the cessation of desire is designated by the same term regardless of how the condition comes about—most commonly as a short-lasting aftermath of gratification.

8 For a discussion of the many ways in which correlation can arise between variables and, hence, of the many possible interpretations of correlations, see Appendix C.

9 The rank-difference correlation is a variant of the usual correlation coefficient, the only difference being that we take the rank position as the score. Thus, percentage of Negroes has a rank of one in all three boroughs. The correlation between delinquency rate and drug rate is, of course, not included in these rank-difference correlations or in the ranking of the coefficients in Manhattan, since its value was not determined for the other boroughs.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|