2 The Neighborhood Distribution of Juvenile Drug Use in New York City

| Books - Narcotics Delinquency & Social Policy |

Drug Abuse

2 The Neighborhood Distribution of Juvenile Drug Use in New York City

No one knows—and the writers of this book are no exception—how many people, under twenty-one or over, illicitly take drugs. The great bulk of available data are based on arrests. Unfortunately, there is no simple relationship between the number of arrests and the number of users. It depends on the amount of police activity. It depends on the adaptability of those who possess drugs to the possibilities of detection and the rate at which law enforcement officials accommodate themselves to current skills and techniques of evading detection. It depends on the kind of police activity.

Thus, if the police are concentrating on primary sources of distribution, we may expect the relative number of arrests to go down, simply because it is a more difficult job to get at the primary sources and takes more man-hours of police energy. Contrariwise, if the police are concentrating on the consumer end of the business, the number of arrests will rise. The easiest way to produce a large number of arrests is to concentrate on the known addicts at large in the community. The number of arrests will also reflect the disposition of cases in the courts, and probably in a curvilinear fashion, at that. Thus, if the courts go hard on the police, the latter can only accommodate themselves by trying to build stronger cases and letting the weaker cases go. On the other hand, if the courts go hard on the persons arrested, the proportion of users in circulation at any given time—and hence the number available for arrest—goes down. But an addict serving a jail sentence is still an addict and, as such, to be counted in the population of users. Our point is that a given user may be represented in the arrest statistics for a given period from zero to many times, depending on what the police and courts are doing in that period. Lest we be misunderstood, let us emphasize that we are talking about counting the number of users and not about the effects of law enforcement on the long-range growth or decline of this population.

We have similar problems with hospital admission statistics. Not only will the number of, say, voluntary first admissions vary with the available hospital facilities, but also with the activities of the police and the courts. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that, the more difficult life becomes for the addict, the more likely he is to seek medical assistance. Experience with addicts also indicates that they do not always seek hospitalization with the hope of being cured, but rather with the intention of reducing the habit to more manageable proportions or with the intention of restoring the power of the drug to produce a "kick." The pressure on the hospitals at any given time will, consequently, vary with the numbers of individuals who are finding their habit unmanageable and whose accommodation to the drug has reached a point where it no longer satisfies, but whose physical dependence is such that they cannot, by themselves, abstain. And the availability of hospital facilities is not a simple function of the number of hospital beds devoted to addicts. For a given number of beds, the number of admissions (new or total) varies with the average length of stay of patients, which, in turn, varies in complex ways with hospital policies.

There are other problems and a more general semantic issue involved in the statistics. They may be illustrated by two of the most carefully compiled sets of statistics available. Referring to a carefully compiled list of narcotics-involved individuals drawn from many sources in addition to Police Department arrests and meticulously eliminating duplications of cases, Inspector Joseph L. Coyle (at that time in charge of the Narcotics Squad of the New York City Police Department) wrote: "From July 1, 1952, to February 28, 1958, . . . it shows that there are 22,909 drug addicts in the City of New York. . .

Despite the fact that, elsewhere in the same article, Coyle informs us that 71/2 per cent of the 4,278 arrests in 1957 were "nonaddict sellers," there is reason to believe that the basic list which produces the "22,909 drug addicts" does not exclude violators of the narcotics laws who do not themselves use narcotics. This is the first problem with the statistics. The law does not make the actual use of narcotics illegal; it makes the illicit possession and transmission of narcotics and the possession of equipment the probable use of which is for taking narcotics illega1.2 We have reason to believe that no serious errors are introduced on this score into the statistics of juvenile users (under age twenty-one), but we do not know how to evaluate the situation in the case of adults. Coyle's "71/2 per cent" may offer a maximum estimate of the error, but it is difficult to evaluate, since it is based on only one year's experience, on arrests rather than on persons, and on total figures that include the cases of juveniles.

A major problem in Coyle's list was that, once a person got on the list, there was no way short of death to get him off it. The list did eliminate the names of cases known to have died, by checking New York City death-records. Departures from the city and deaths in other localities presumably could not be checked. If a person has not taken drugs since the last time he has been known to have done so, does he still belong on the list? The issue is not a simple one. If he has been truly addicted, there is reason to believe that the stoppage is only temporary. In such a case, there is likely to be no great error in continuing to list him as a user. Not everyone, however, who has got involved with the law as a consequence of drug usage or who is otherwise known to have been using drugs is an addict. If a nonaddict user stops, there is no reason to continue to list him as a user; even if he were to resume at some time, this would require, so to speak, a reinfection.

A somewhat similar procedure on a national scale has been adopted by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), beginning January 1, 1953.3 This list has the virtue of providing some means of transferring a name from it and is not seriously affected by changes of residence within the country, although the removal of the dead is under somewhat less adequate control. Persons who may have been listed as addicts but who have developed some organic pathology that requires narcotic medication are transferred from the active file, since they are considered to be receiving drugs under a physician's supervision. The major basis of transfer from the active file, however, is that the case has not been reported as a user for a period of five years. Cases removed from the active file may, of course, be returned to it if they are again reported as illicit users.

Of special interest is the report by Charles Winick concerning the individuals who were first added to the list during the calendar year 1955 and who were transferred to the inactive file during 1960 on the basis of the five-year lapse—that is, let us emphasize, during the first year in which they could have become eligible for such transfer. There were 7,234 such cases.

Now, it would obviously be desirable to know what proportion these inactivated cases are of the number originally placed on the list in 1955. Unfortunately, the figure is not reported. We are, however, told that 45,391 active addicts were known to the bureau up to the end of 1959 (about 46 per cent of them from New York), and this number must include the 7,234 of the 1955 series of cases, since the latter did not become inactive until 1960. On the assumption that approximately the same number of cases were added each year, there would have been one seventh of 45,391, or 6,485, names added to the list in 1955. That is, on this assumption, more than 100 per cent of those originally on the list became inactive at the first possible opportunity to do so. Since we cannot believe in such remarkable curative effects from being put on a list, we take it that the assumption of equal yearly increments is wrong. It seems obvious, however, that the proportion who become inactive at the first possible opportunity must be astonishingly large; 7,234 is already 16 per cent of the entire seven-year crop of 45,391.4

The reason that our assumption of equal yearly increments in the growth of the list was so far off the mark also seems rather obvious. In early years, the file must have been loaded with old-timers. That is, there was a reservoir from which to establish the file. A large proportion of the cases were not really new cases; they had been known to various agencies for a long time and were new only in the sense that they were newly added to a recently established file. Even among our 7,234 inactivated cases, 9 per cent are listed as having been addicted for from fifteen to fifty-six years. But, if the original 1955 list was heavily loaded with hard-core old-timers, then a high proportion of inactivated cases is all the more impressive.

There is another astonishing fact about the 7,234 cases transferred to the inactive file in 1960. More than a third of them are listed as having been addicted for only five years before being transferred. Since, by the FBN classification system, a person is listed as an addict until he has been unreported for five years, we take it that these 2,473 individuals were not only not known to have taken drugs in the five years subsequent to 1955, but also that they had no history of addiction prior to 1955; that is, the five years of "addiction" are the five years during which they had to stay drug-free (at least in the sense of being unreported as users) in order to be transferred to the inactive file. By analogy, a postoperative cancer case who has remained symptom-free for five years after the operation would not be regarded as "cured" until the five years had elapsed. He would still be listed as suffering from cancer for the five years in which he was completely symptom-free. A more familiar way of thinking about this is that such a case is cured by the operation, even though the proof of the cure is not available for five years. If getting on the list means, as is claimed, that a person was known to have been a regular user of opiates, then these 2,473 individuals were "regular users" only during the course of the year 1955.

In similar fashion, it is common practice to refer to any person who has received treatment in a hospital in connection with a narcotics problem as an "addict," without consideration as to whether he is addicted in any sense other than this. We do not know, however, what proportion of such cases of drug use have relatively minor involvements. Some people have themselves committed, and there is no doubt that they think of themselves as addicted, but this amounts to self-diagnosis without any clear-cut medical criterion. Others may have themselves committed because a frightened parent has persuaded them to do so, even though they may not regard themselves as addicts. Still others accept commitment because a benevolent judge has offered this as an alternative to jail in the light of a first offense and testimony as to their prior good character. Sometimes, a judge will offer the hospitalization alternative to a second or third offender. Such patients are, of course, repeaters; but is sheer repetition sufficient to define addiction? In connection with other crimes, we often interpret repetition in terms -of a continuance of the conditions that led to the first violation. Why should we not do likewise here? In any case, it is almost a certainty that the most seriously involved people are more likely to wind up in jail than in a hospital.

Meaning and Varieties of Addiction

There are some important distinctions to be made before we can hope to be clear on the issues involved in the definition of addiction. There are, in the first place, more-or-less regular users. Some unknown proportion of these become physiologically dependent; that is, if they do not get the drug, symptoms of bodily (and, in some instances, psychic) malfunctioning—ranging from perspiration, nausea, and cramps to death—appear. It is likely that individuals differ in their susceptibility to dependence,5 and we know of individuals who have used heroin for several years on a more-or-less regular week-end basis and then, apparently without difficulty, quit.6

Dependence is, however, not all there is to addiction. If it were, then it would be easy to treat and cure, for all that would be needed would be to subject the addict to a period of enforced abstinence. Alas, the cure is not so simple. All too often the addict so treated emerges from jail or the hospital purged of his dependence but eager and scarcely able to wait for his first "shot." Some addicts have themselves committed so that they can lose their tolerance (and, more-or-less incidentally, except where a major aim is to make the habit more manageable, their dependence), so that they can once again derive full enjoyment from drugs. The more-or-less periodic cycle of arrests and the associated enforced withdrawal serves a similar function for those who do not have whatever it takes to seek withdrawal on their own.

On the other hand, it is conceivable that a person might become dependent without even knowing that he has been receiving narcotics. This could occur in the course of medical treatment, where the patient might associate the withdrawal symptoms with the illness for which the narcotics were prescribed, recover, and never return to the use of narcotics. It is doubtful whether such a person would be properly called an addict at all, even in the past tense. Prior to the Harrison Act, considerable numbers of individuals must have developed dependence on opiates as a result of their indiscriminate use of proprietary medicines. They must have experienced considerable discomfort when the formulas were changed in response to the new law, but there is no evidence to indicate that many of them did not quickly adjust to the new state of affairs without ever realizing what had been ailing them immediately after they started taking the new formula.

Knowledge of one's dependence and of the role of the drugs in alleviating the distress of withdrawal is, to Lindesmith,7 an indispensable ingredient of the definition of a true addict. Actually, there are two, or perhaps three, aspects to Lindesmith's criterion: the recognition of dependence; the consequent change in one's self-concept and in preoccupation (the "frantic-junkie" state); and the subsequent assimilation into the addict culture, with a seeking out of others of one's kind and the development of skills, customs, and language necessary to the maintenance of one's supply. Becker8 has described an essentially similar process involved in the course of becoming a confirmed marijuana user, a drug which does not produce dependence. Hence, the two aspects—the recognition of dependence, on the one hand, and the change in self-definition and the associated, so to speak, switch in subcultural identification, on the other.

The parallel between Becker's analysis of becoming a confirmed marijuana-user and Lindesmith's analysis of opiate addiction suggests that the recognition of dependence is not the important part of Linde-smith's criterion. This is also obvious in the case of an "addict" in a temporarily dependency-free state. Note, also, that the recognition of dependence is possible without any of the rest following; it may facilitate the changed definition of the self and the correspondingly altered pattern of existence, but it is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition.

Wikler° has made a number of observations which seem to have considerable bearing on the Lindesmith criterion. The first again emphasizes the relative unimportance of the recognition of dependence. It is that, under experimental conditions, addicts are quite willing to undergo abrupt withdrawal, sometimes with severe withdrawal reactions, for relatively paltry rewards, for instance, the reduction of a long prison sentence by a few days or weeks.

The second was made in the course of a study of a patient during experimental readdiction to morphine. After he had developed a high degree of tolerance so that he could no longer experience the euphoric effects that he had at first achieved, he noted that he was getting another kind of gratification, viz., relief from the abstinence discomfort that developed toward the end of the intervals between injections. The patient himself drew an analogy to the development of appetite in connection with food. He remarked, for instance, that although a steak always tastes good, it tastes even better when one is hungry. "In other words," Wikler comments, "with the development of `pharmacogenic dependence,' a continuous cycle of drug-induced 'need' and 'gratification' develops which can motivate behaviour in much the same way as the recurrent cycles of hunger, thirst or other 'primary needs' and gratifications thereof, in normal life." Related to this is Wikler's observation that "postaddicts" have sometimes noted the recurrence of withdrawal symptoms long after they have been withdrawn from the drug when they find themselves in situations in which narcotic drugs are readily available. This is analogous to the markedly increased salivation which most people are apt to experience when they think of or see highly appetizing foods even though they may not be at all hungry. The last of Wikler's observations to which we want to refer concerns the preoccupation of narcotic addicts with "hustling" (the activities of the addict aimed at keeping himself supplied with the drug), not merely when they are under pressure to do so, but in their thoughts and conversation in the hospital environment after they have been withdrawn, especially in the presence of other "addicts" and "postaddicts."

One of the present writers has elsewhere elaborated a general theory of motivation and personality structure,1° some aspects of which are relevant here. The behaving individual, according to this theory, develops enduring concerns with regard to the assurance of the conditions of satisfying recurring needs. These enduring concerns come to play a larger role in the life of the individual than the needs that originally gave rise to them, and indeed they acquire independence of the needs. As concerns with the conditions of satisfying motives, they incorporate the individual's conception of the self and of the relevant physical and social environment, and they require the development of relevant knowledges, skills, statuses, and personal relationships. They acquire manifold interdependencies which serve to redefine them. Reflexively or retroflexively, they have bearing on the self. The system that includes the self-image and these interdependent enduring concerns is the personality.

We cannot develop here this interpretation of the nature of personality fully or elaborate in detail its bearing on the observations of Linde-smith and Wikler with regard to addicts. In a word, however, it seems to us that what Lindesmith and Wikler have, between them, described is the emergence of a personality structure built on narcotics, an associated self-image, and a related way of life. Even more briefly, what they have described is a pattern of total personal involvement with narcotics.

There is still another aspect of addiction that must be noted. This is the fact of craving, a phenomenon that will be familiar, in lesser degree, to the cigarette-smoker when he is deprived of his customary drug, one that does not produce dependence.11 The full-blown addict is not content with a maintenance dose that will prevent the withdrawal syndrome. He craves the experience of the "high" and will go to great lengths to achieve it. Again, the familiar experience of cigarettes may help to illustrate the point. It often happens that, because of illness or overindulgence, one loses one's satisfaction in smoking. Many a cigarette-smoker will, under these circumstances, not simply be content with not smoking until he can again experience gratification; he will be actively frustrated and may again and again futilely light a cigarette, hoping against hope. Or sex: the failure to achieve the acme of gratification does not commonly result in a simple loss of interest or an acceptance of the banality of the experience, but often in a frantic preoccupation with, and desperate efforts to achieve, the denied fulfillment. Or, for that matter, food: how can one account for the sense of frustration over a meal that assuages hunger, but does not yield the anticipated gratification? Our point is not that these cravings are necessarily of the same nature, but simply that craving involves something beyond the elimination of bodily tensions or the awareness of having done what needed to be done; craving involves the demand for gratification that can be subjectively experienced as something special.

Craving undoubtedly has its ups and downs, not only in relation to the recency of gratification, but to mood cycles and the ups and downs of living. One addict, for instance, known to one agency for many years, apparently has no difficulty in staying away from drugs as long as the daily affairs of living proceed smoothly. As soon as any difficulty develops, however, he goes back on drugs. The phenomenon should be familiar to tobacco-smokers who commonly find themselves in periods of heavier smoking than usual. It is also involved in the relapse of apparently cured addicts who, after relatively long periods of abstention, go back on drugs after a quarrel, an affront, getting a new job, meeting an attractive girl, or the like.

Reviewing these distinctions, it becomes apparent that we have 'described three dimensions of addiction: degree of physiological dependence, degree of total personal involvement with narcotics, and degree- of craving. To facilitate the examination of this three-dimensional scheme, let us dichotomize each of the dimensions:

1. Presence versus absence of some significant degree of physiological dependence.

2. Presence versus absence of some significant degree of total personal involvement with narcotics.

3. Presence versus absence of some significant degree of cravingi.e., regardless of the degree of physiological dependence, having intensification of the desire for a "high" experience with the passage of time since the last "high" and/or with increased stress from whatever source.

Compounding these three dimensions, it is obvious that we can conceive of eight types of individuals, seven of them being in some sense "addicted." Or if, as seems more sensible, we were to reduce the first dichotomy to subordinate status because of its shorter-range significance, we would have four types, three of which could be thought of as "addicts": (1) totally involved, but without craving; (2) having craving, but not totally involved; and (3) having both craving and total involvement. Each of these types would include individuals who, at any given time, are dependent and others who are not. To these three "addict" types, we would have to add a fourth "addict" type, that is, individuals who have a history of repeated dependence without indications of either total involvement or craving, again with some of them currently dependent and others not. Note that we have not included as an "addict" type individuals who are currently dependent, but who have no such history and who show no signs of total involvement or craving; nor have we included individuals with one-time history of dependence, but no further recurrence; nor have we included as an "addict" type users with no history of dependence and with no signs of total involvement or craving.

It is a virtual certainty that cases of the first three types actually exist, and it seems extremely likely that there actually are cases of the fourth type. The fact of the matter is that no one has attempted to apply such a typological classification, and there are consequently no data as to the proportion of the total "addict" population that each of the types comprises.

Yet it is perfectly obvious that these types pose differing problems in treatment and that they are likely to have quite different etiological histories and prognoses. Consequently, it is clear that it is meaningless simply to identify an individual as an "addict."

Consider, for instance, the so-called British system of narcotics control.'2 In England, it is discretionary with the individual physician whether to keep an addict on maintenance doses of opiates, i.e., the minimum dosage that will prevent withdrawal reactions. A substantial proportion of British addicts are apparently willing to continue on this basis. Given the fact of tolerance, it is a certainty that these addicts cannot experience a "high" under these conditions. From the point of view of subjective gratification related to the direct pharmacologic effects of the drug, these addicts are getting no returns. From this point of view, they would be just as well off if they underwent some humane form of withdrawal treatment and then simply stayed clear of the drug. Why do they not? It seems clear that they must be getting some other kind of gratification. That is, they must be getting involvement gratifications rather than the satisfaction of cravings. In other words, these must be Type 1 cases.

In the United States, there is a great deal of agitation for the adoption of the British system, and it is highly likely that, within the next few years, this system will be introduced on an experimental basis. The ultimate decision of whether to adopt the system as general policy will, therefore, hinge on the selection of the experimental cases and on how they behave under this regimen. It thus seems to be important to select Type 1 cases if the experiment is to be successful. By the same token, however, if the experiment is successful, it would not follow that this kind of treatment would work at all in Type 2 and Type 3 cases.

Actually, there is reason to believe that a large proportion of American addicts are Type 1 or Type 4 cases. This follows from the fact that the withdrawal reactions commonly observed are as a rule relatively mild. This fact is usually explained on the assumption that black market heroin is so heavily diluted that the real dosages are too small to develop serious dependency. Again, however, we come up against the fact of tolerance. Continuing on standard available dosages must rather quickly eliminate any true "high." In principle, there is nothing to stop an addict from taking two or three or five or ten "packs" of heroin per "shot" or as many as he needs to give him an adequate "high." That is, the low true dosage per pack does not offer any rational explanation of the relatively low degree of dependency in most addicts. Again, a more plausible explanation is that they are seeking involvement gratifications and have relatively little true craving (Type 1) or that they are getting no gratifications from the drug at all, but are simply unable to resist the pressures of their milieus.

All of this is thoroughly plausible and, to us, convincing. Is it also correct? We will never know until a considerable body of research is available that takes these (or better) distinctions into account. Our own studies did not do so; we did not know enough.

The Number of New Cases in New York City

Desirable as it may be to know how many cases there are at any given time and how many of each type, it does not follow that, lacking this information, there is no point in knowing how many drug-users, not necessarily even addicts, first come to public attention in a given period. Whether or not a new case reforms, continues along lines characteristic of his type, or develops into a more serious type, there can be no doubt that, as time goes on, an increasing proportion of seriously involved cases must come from a reservoir of recent cases. The more we learn about the formation of the reservoir, the better off we are. If we are interested in compiling a list of cases as of their first becoming known, it is because of our concern with the reservoir and not because we think that it can tell us the number of "addicts."

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE CASE FILE

Our primary sources of cases were the courts and municipal hospitals in the three boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. The decision to limit the study to these boroughs developed out of early discussions with police and court officials who reported only a negligible drug problem in the boroughs of Queens and Richmond." These discussions also set the starting date for the file; 1949 was the year in which adolescent drug cases began to come to the attention of official agencies in sizable numbers." It was also decided that we would limit ourselves to the category of cases which includes the vast majority of all juvenile users—males from sixteen to twenty-one years of age." Some data on girls in the sixteen-to-twenty bracket and on children under sixteen were gathered, however, in order to round out the picture.

Data were collected in two series. The earlier series was for the fortysix—month period beginning January 1, 1949, and the later series for the thirty-six—month period from November 1, 1952, to October 31, 1955.16 The lists of drug-users and other drug-connected cases were combined into a single file, that is, entries that appeared in several source files or more than once in the files of a single agency were consolidated into a single case listing with a notation as to the earliest known date of drug involvement.

The basic source of our information was the docket books of Magistrates' Courts. Identifying data and home addresses at the time of first contact with the court were copied from Youth Term and Felony Court docket books for youngsters charged with possession or sale of narcotics or of such narcotics paraphernalia as a bent spoon or hypodermic syringe. Those who applied for voluntary commitment and treatment at Riker's Island or Riverside Hospital were added to our list from the records of the Chief Magistrates' Term Court and Narcotics Term Court.

Prior to July, 1952, when Riverside Hospital opened, treatment facilities for youthful drug addicts were in operation at the psychiatric divisions of Bellevue and Kings County hospitals. These facilities accountlor an estimated 95 per cent of all addicted individuals treated in municipal hospitals during the first period (January 1, 1949, to November 1, 1952) of our study. By adding these cases to our list, we were able to include many self-admissions for whom there was no court record. Subsequent to the opening of Riverside Hospital, juvenile narcotics cases received medical treatment in public facilities only at Riker's Island (for detoxification) or at Riverside Hospital. According to informed opinion, a negligible number of cases, if any, receive private treatment without being known to one or another public agency.

In order to include drug-users appearing before the courts on charges other than violation of the narcotics laws, access was obtained to the records of the Probation Department of the Magistrates' Courts and of the Youth Council Bureau, a private organization attached to the district attorney's office in each borough. Since January 1, 1949, the Probation Department has been maintaining a separate file of narcotics cases for purposes of study. Similarly, the Youth Council Bureau has also indicated cases of narcotics involvement in its files. Social workers in this bureau attempt to interview every youth under twenty who is arraigned in one of the youth parts of the Magistrates' or higher courts. Until late in 1952, the bureau gave a medical examination to those youths who were arrested on a nonnarcotics charge but suspected of using drugs, as well as to youngsters charged with narcotics violations."

TOTAL NEW CASES

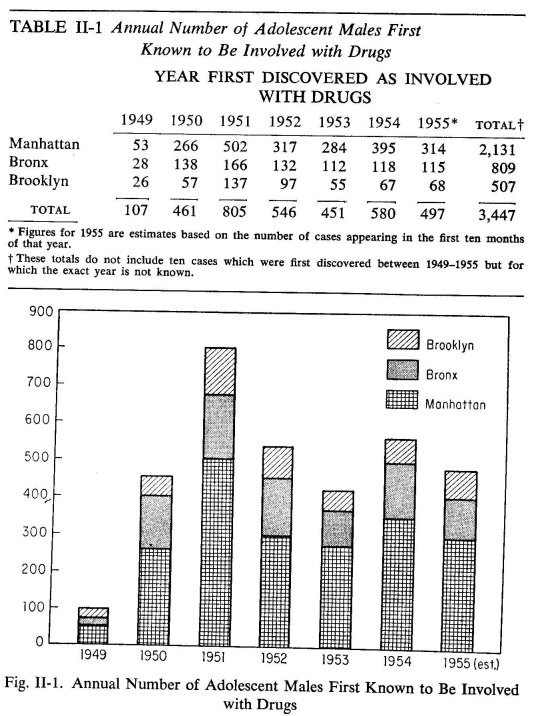

A total of 3,457 new cases of boys in the sixteen-to-twenty age bracket were discovered to be involved with narcotics during the seven-year period. On the average, about five hundred new cases of boys and young men from sixteen to twenty-one have come to the attention of the city courts and hospitals each year between 1949 and 1955. The majority of these youngsters (62 per cent) are from Manhattan. The Bronx accounts for 23 per cent of the cases, whereas only 15 percent of them are from Brooklyn.18

There has been some variation from year to year in the number of cases discovered, particularly for Manhattan (see Figure II-1 and Table II-1). The peak year was 1951, when over 800 new cases appeared in the courts and hospitals. This was almost eight times the number of cases known in 1949, the first year for which we have data. Since the peak year of 1951, there has been a moderate decline in each of the boroughs, and, since then, the number of new cases seems to have stabilized at about five hundred per year over-a11.19

These figures suggest that the drug problem has become a chronic one in New York City; there is no indication of a falling off of cases over the long run. Actually, there were probably more cases than we are able to show, particularly for the years 1953-1955, when there was an unavoidable weakening in the efficiency of case-finding procedures compared to the earlier years.2°

JUVENILE PUSHERS ARE ALSO USERS

Thus far, we have described our cases as involved with, rather than as users of, drugs. To what extent do actual users occur among the cases we have collected? For the 1,845 cases appearing in our first series, each boy was classified as a known user on the basis of the record if he (1) was given treatment for use at some hospital, (2) confessed to the use of drugs, (3) was charged with possession of equipment used in the injection of narcotics, or (4) was discovered in the course of a special medical examination to have body marks associated with heroin use. All other cases in this series were classified as "use status not established." Two-thirds of the cases could clearly be described as users of drugs on the basis of these criteria. In general, the third about whom we were not certain appeared in Magistrates' Court docket books charged with possession or sale of narcotics and did not appear in other consulted sources which gave more detailed information on the use of drugs. The following collateral evidence, however, suggests that, although concrete information is missing, most of the boys in this latter group were probably also users as well as sellers of drugs.

1. The Elmira Reception Center processes and sends to correctional institutions many of the boys under twenty-one who have been found guilty of charges in the New York City courts. The following data from the reception center were made available to us:

Of boys received and found guilty on charges of possession or sale of drugs (mainly from New York City), at least 95 per cent were found on examination to be drug-users. If we may generalize this information to the 609 cases in our file whose drug-use status is uncertain, it is clear that the vast majority of these boys are probably users as well as pushers. Since there is reason to believe that not all drug-users are detected by the time they have left the reception center, the 95 per-cent figure, high as it is, may well be an underestimate.21

2. Data from our study of drug use in eighteen streets gangs indicate that 80 per cent of the sellers in these gangs are known to have used heroin and an additional 14 per cent to have used marijuana. Again, almogt 95 per cent of the boys who have a history of drug-selling have also been users of drugs.

DRUGS USED

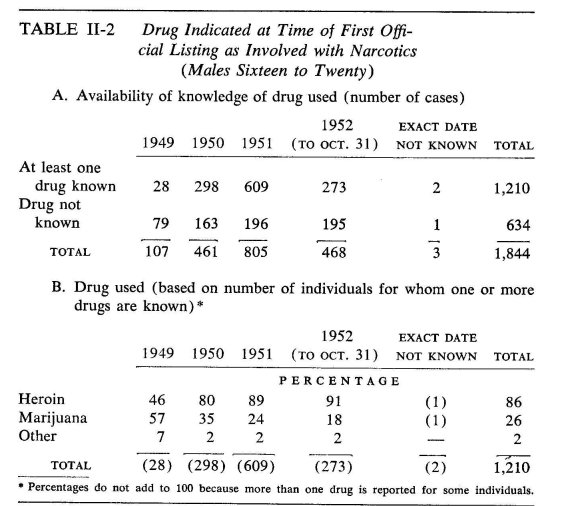

Table II-2 shows the type of drug used when the youth was first discovered to be involved with drugs. In about one-third of the cases, the name of the drug did not appear in the source or sources consulted. In more than 80 per cent of the cases where some drug was specified, heroin was listed.22 The table also shows that mention of this drug has been rising each year of the series.

For one-quarter of the cases, marijuana was specified; other drugs, such as morphine and cocaine, were only rarely listed.

Some boys were involved with both marijuana and heroin. The figures for marijuana are probably a gross underestimation, since some sources probably listed only the most serious or "current" drug involvement. It also seems likely that involvement with the use of heroin is more likely to be detected than that with marijuana, which is not a dependency-producing drug.

BOROUGH DISTRIBUTION OF CASES IN THE EARLY PERIOD

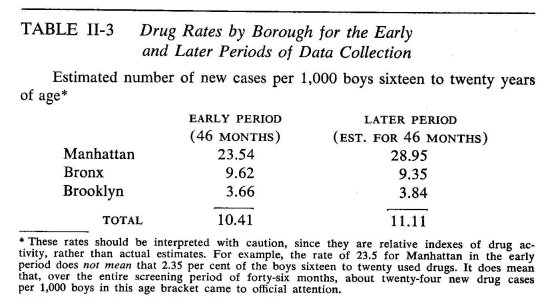

Rates were calculated for each borough indicating the number of drug cases per 1,000 boys in the sixteen-to-twenty age bracket.23 Table II-3 presents these data, which show a marked difference among the boroughs. Manhattan has the highest rate of juvenile drug activity; the Bronx and Brooklyn are far below it in incidence of new cases. It is also apparent that there has been no substantial change over the period we have studied in the rate at which the three boroughs produce new cases.

To summarize, the over-all picture in terms both of numbers of new cases 'and of borough drug rates has remained fairly constant over the seven-year period, despite efforts to cope with the problem.

Is Drug Use Evenly Distributed?

As everyone knows, a city population is not homogeneously distributed with respect to income, religion, race, nationality, and numerous other characteristics. The various sections of the city also differ in many other ways—in amount of industrial activity, for instance, and rate of population turnover. Hence, if we find that some disease does not strike evenly over a city, we have reason to suspect that clues to the full story of the spread of that disease are to be found in an examination of the differences between the areas where the disease strikes harder and those in which it strikes more lightly. This is true even when a specific agent can be described as the "cause" of the disease. Tuberculosis and syphilis, for instance, are diseases which depend on specific germs; but the full stories of the spread of these and other diseases depend on (1) patterns of personal contact and other conditions which help or prevent the germs' transmission; (2) factors that affect individual resistance to the germs, including constitutional factors and hygienic practices; (3) the availability of hygienic resources; and (4) factors that affect the utilization of resources.

In brief, if pathology (whether physical, psychological, or social) strikes equally in all strata of society, then we have no reason to suspect that factors related to any of the dimensions of social stratification have anything to do with the spread of that pathology. If, contrariwise, the pathology does not strike evenly, then the lines of stratification along which the differentials in incidence occur provide important clues as to factors responsible for the spread.

This, then, was our first question. Is the illicit use of narcotics evenly distributed over the city, or is it unevenly distributed, as has been found to be the case for a variety of forms of pathology ranging from tuberculosis and heart disease, on one extreme, through venereal and mental disease to juvenile delinquency on the other? The answer to these questions is an unequivocal verdict of unevenly.

These data refer to the "earlier period" of January 1, 1949, to November 1, 1952. The reason for this restriction is simple. To say that there are more cases in one area than in another does not mean anything unless we also know what the maximum possible numbers of cases are in these areas. Suppose, for instance, there are ten cases in an area which has one hundred boys in the specified age range, sixteen through twenty. Suppose, further, that there are fifteen cases in another area which has one thousand boys in the designated age range. What does it mean to say that there are more cases in the second area than in the first? Though true, such a statement can be extremely misleading. The "disease" obviously strikes much more heavily in the first area, where one boy out of ten is afflicted, than in the second, where the rate is 1.5 per hundred. To compare areas on the degree to which a disease strikes, we need rates, not absolute numbers. But we are dependent on the 1950 census for the base figures on which these rates are calculated; the further we get from the 1950 census, the less certain we can be that the census figures reflect a true state of affairs; hence the need to restrict the time involved. The bulk of the analysis in the following chapter is based on additional census data; the same consideration applies to these data.

Our basic unit of analysis is the census tract. This is the smallest geographic unit—usually, an area of about four to six square blocks in the city—on which the bulk of census information is available.a The census tracts are laid out to be as socially homogeneous as possible, although there is some deviation from this principle in order to maintain the historical comparability of census tract information.

Each census tract with three or more cases24 was colored in on a map. In addition, any tract with one or two cases was also marked if it was adjacent to a tract that had at lease three cases. The result was—except for two isolated tracts in the Bronx which met the primary criterion of three or more cases—a series of sizable "islands" in the three boroughs. These "islands" (including the two tracts just mentioned) we have designated, with some apologies for the emotionally loaded term, "epidemic areas." We do not know how many cases justify the possibly alarmist implications of the word "epidemic." We do not intend any such implications; the reader will have to form his own opinions on this score. We want to convey only that there are clearly more cases in these areas than elsewhere, and the reader will not be misled if he bears our usage in mind. As to the cases not included in the epidemic areas, it is our assumption that they are too sporadically distributed to be much illuminated by the present approach. Preliminary analyses of the data also suggested that the statistical trends do not hold for the areas with sporadically distributed cases.

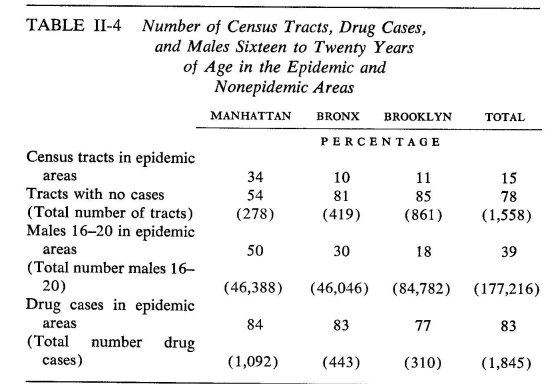

That there are more cases in these areas in a relative as well as in an absolute sense is evident from Table II-4. For the three boroughs combined,15 per cent of the tracts, containing 29 per cent of the sixteento-twenty–year–old boys, contribute 83 per cent of the cases. Even in Manhattan, where the discrepancies are not nearly so great as in the other two boroughs, one-third of the tracts, containing half the boys, contribute 84 per cent of the cases.

Incidence maps clearly indicate that Harlem was the section with the most drug activity among boys in the sixteen-to-twenty age range. In the Bronx, the south-central (Morrisania) portion of the borough had the highest concentration of drug-involved cases, with some sections within this region reaching the high levels characteristic of Harlem. The pattern in Brooklyn was similar to that of the other boroughs, but the level of drug activity was much lower, even in the areas of relatively high incidence. Most of the areas in Brooklyn had few or no cases. The relatively high areas formed a belt from Red Hook in the west through the Fort Green and Bedford Stuyvesant areas to Brownsville in the east.

Our first question, then, seems to be answered decisively in favor of the uneven distribution of drug involvement. But can we trust the answer? After all, we have been working only with known cases. Is it not possible that there are many unknown cases and that the uneven distribution reflects differences in the detectability of cases? That is, is it not possible that the true distribution is even, but that cases are more readily detected in certain areas than in others? If this possibility were taken seriously, it would certainly put our findings in a quite different light. There are, however, at least five lines of reasoning and evidence that, taken together, seem to us to demonstrate convincingly that the distributions are, in fact, much as we have found them.

DOES THE DETECTION OF CASES BIAS THE DISTRIBUTION?

In the first place, to maintain the hypothesis of even distribution we would have to assume that there is a large number of undetected cases. Even a crude calculation on the basis of the data in Table II-1 shows that there are about 35 cases per thousand in what we have called the epidemic areas. With about 125,000 boys in the nonepidemic areas, there would have to be over 4,000 cases in these areas just to maintain the same average rate. This calculation does not take into account the differences in rate of known cases within the epidemic areas. To establish complete homogeneity of rates, we should work from the highest rates in the epidemic areas. At, say, 100 per thousand, we would have to assume about 12,500 cases in the nonepidemic areas plus the undetected cases in the areas of lower known rates within the epidemic areas. Even this would have to be based on the assumption that there are few, if any, undetected cases in the census tracts of the highest known rates, an assumption which we have ample reason to question. From a study to be reported on below, we know that cases which are detected average about two years from their initial trial of heroin to their detection. From another study to be discussed below, we have ninety-four heroin-users in street gangs, two-thirds of whom have been using the drug for two years or longer, and three-fourths of whom have never been picked up. These gangs are in high-use areas. The resulting figures are simply too high to be credible, and we must consequently challenge the assumptions by which they are reached, that is, we must adopt the assumption that the incidence of drug involvement is, in fact, not evenly distributed.

In the second place, drug involvement is not the kind of illicit activity that can be carried on alone or even exclusively in the company of a small number of friends. The case is not comparable, say, to finding a car parked on the street with the key in the ignition and deciding to go for a joy ride. Reefers and packets of heroin are not conveniently parked on the street; nor axe they obtainable by the simple process of a few youngsters deciding to raise hell. Access to these drugs presupposes contact with a highly illegal traffic which is a target of vigorous police activity on federal, state, and local levels. It is axiomatic, however, that, the more people involved in the commission of a crime, the more detectable that crime is. It is further axiomatic that, the more frequently a crime is committed, the more likely is it to be detected. Moreover, unlike car theft or statutory rape, the evidence of drug use is apparent after the fact. All of this means that, if our figures are seriously biased, they are biased in the direction of more serious involvement. That is, the more peripherally and the less frequently a youngster is involved, the more likely he is to escape the network of detection.

There simply cannot be a high degree of involvement with narcotics among significant numbers of youngsters without its drawing the attention of the police, school authorities, and others. This finding is reinforced by the patterns of school attendance in the epidemic and nonepidemic areas. Relatively few youngsters leave school at the age of sixteen in the nonepidemic areas, and, consequently, a much higher proportion remain under the surveillance of school authorities.

In the third place, we attempted a direct check on the representativeness of our distributions. This involved a survey of community agencies, recreation and educational centers, private hospitals, and medical clinics throughout the three boroughs. Responsible officials in a total of 175 agencies were asked whether their agencies had had contact since January 1, 1949, with narcotics-involved youths under twenty-one years of age. Of the agencies contacted, 128 answered either by mail or by telephone, and thirty-four reported contact with one or more cases. Of the latter, fourteen agencies functioned city-wide. Two of these agencies furnished the addresses of the 192 cases known to them. The vast majority of these had home addresses in areas of high drug rate, as we had calculated the latter on the basis of our court and public hospital data. Twenty local agencies, serving more limited areas, also reported one or more cases. Half of these agencies were located in tracts in which our estimated drug rate exceeded five per thousand. By contrast, only 15 per cent of the agencies reporting no cases were located in such tracts. In evaluating the latter data, it should be borne in mind that the precise area served by even a local agency is difficult to specify. Hence, in the case of such an agency physically located in a tract of zero drug rate but reporting one or more cases, the cases themselves may have arisen in tracts of some drug incidence according to our original figures. The result of this survey was to reinforce our belief that the distributions we obtained were, in fact, fairly representative of the true state of affairs.

The fourth and fifth lines of evidence involve internal checks on our data. In forming our basic series of cases, we had collected series of females and of children under sixteen. The relative incidence in the three boroughs and the years of smallest and greatest incidence were identical for males aged sixteen to twenty, females in that age range, and children under sixteen. Similarly, there were approximately the same ratios of males to females above and below sixteen. The consistency of these findings for these three groups of individuals who generally come to the attention of public officials under quite different circumstances suggests that our data for the males in the sixteen-totwenty age group are not seriously distorted by sampling biases.

Finally, we separated from our sixteen-to-twenty male series the 273 cases who first became known as drug-involved to Bellevue or Kings County hospitals. The remainder were, in the main, cases first known to the police or the courts, although they included a small number of self-commitments to Riker's Island and, after July, 1952, Riverside hospitals. For practical reasons, the latter could not be segregated, but there were not enough of them during the period under study to materially affect the comparisons about to be described.

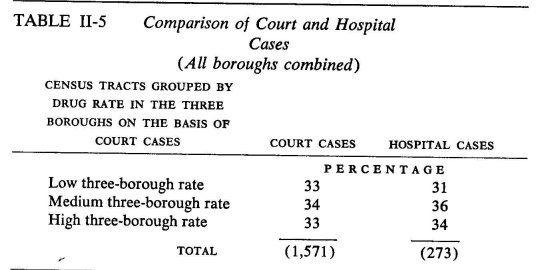

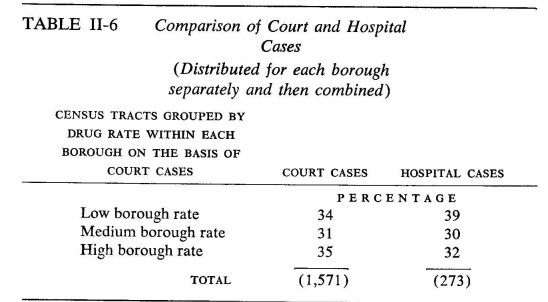

On the basis of the larger series, we divided the census tracts in which the home addresses were located into three groups—low, medium, and high rates—with approximately one-third of the cases in each group. The 273 hospital-initiated cases were then also tracted, and, as it turned out, virtually the same proportions came from each group of tracts. (See Table II-5.) As one might expect from Table II-4, there are interborough differences in the incidence of low-, medium-, and high-rate tracts. We therefore made the same kind of comparison on a within-borough basis (a procedure which has the effect of eliminating the between-borough differences from the comparisons), and, again, the distribution of the two series turned out markedly similar. (See Table II-6.)

On the assumption that there are likely to be quite different selective factors involved in determining whether a case first gets to be known to the hospitals or to the police, we were again confirmed in our belief that the geographic distribution of known cases must conform fairly accurately to the true distribution of all cases. All in all, then, we conclude that our answer to the first question stands.

What about the second period for which we have data, from November 1, 1952, through November 1, 1955? As already indicated, this brings us quite far from the base data of the 1950 census. With the help of data kindly made available by the Department of Planning of the City of New York, we were able to estimate the numbers of males in the sixteen-to-twenty age range as of 1954. We could use these estimates as base figures for the later period. These estimates were on a health-area basis, a standard geographical unit established for the compilation of vital statistics; it usually consists of from sixteen to twenty-four square city blocks forming a more-or-less identifiable neighborhood; there are eighty-five health areas in Manhattan, 116 in Brooklyn, and sixty-four in the Bronx. Actually, we made three estimates and averaged them.25

THE LATER PERIOD

Health-area drug rates for the later period were calculated on the basis of these estimates, and these were correlated with the rates for the earlier period. The resulting correlations were .84 in Manhattan, .57 in Brooklyn, and .89 in the Bronx.26 This means that, if healthm areas are arranged in the order of the later-period drug rates, they still tend to be arranged in much the same order as they would be on the basis of the earlier period rates.

The relationships are not perfect, of course; more initially low-rate areas show increases than decreases in rate, and the initially high-rate areas mainly show decreases. Moreover, the amount of change is negatively correlated with initial rate: —.50 and —.52 in Manhattan and the Bronx, respectively, and —.73 in Brooklyn. This means that the health areas with the initially highest rates show the most marked, and those with the initially lowest rates the least marked, changes.

The important point in the investigation of the later-period rates, however, is that the initially high-rate health areas tend to remain high-rate areas and the initially low-rate areas tend to remain low-rate. In other words, if we investigate the socioeconomic correlates of the census-tract drug rates in the earlier period, we are investigating a phenomenon that is probably still with us.27 Beyond this point, the findings just reported with regard to the later-period rates, cannot be taken too seriously. There may be some substance to them; but they may also be, in whole or in part, statistical artifacts) b The section with the most marked increase in drug rate in the three boroughs and presumably the most likely to have really changed is in the lower part of Greenwich Village and the area south of the Village, the section sometimes known as Little Italy.

STATISTICAL FOOTNOTES

a Some census information is tabulated on a block basis. However, because some of the data we wanted are available only on a census tract basis, we had to use the latter to maintain the unity of the analysis. We would have done this in any event. The smaller the geographical unit, the smaller the base number of teen-aged boys. If the base number is quite small, the rate is radically affected by whether, say, one or two cases of drug use are detected. With larger units, errors of detection tend to balance out—i.e., the relative errors vary less from unit to unit—and, because of the larger base numbers, small numbers of undetected cases have relatively little effect on the rates.

b The tendency for initially high-rate tracts to go down and for low-rate tracts to go up may, for instance, be a simple (and statistically expected) consequence of errors of measurement. The statistics we have used are not subject to sampling errors, since we have dealt with specified total populations at specified times. There undoubtedly are, however, errors of measurement. Specifically, with regard to the numerators involved in calculating drug rates (i.e., number of cases), we may define as error any deviation in a given health area or census tract from the over-all proportion of the number of detected cases to the true number of cases. By this definition, errors may be positive or negative and are presumably randomly distributed. In Appendix A, where we describe the method of computing drug rates for the later periôd, it is noted that the numerators involved in computing later-period drug rates are subject to greater errors than those for the earlier period. As to the denominators (number of boys), not even the census is foolproof, and, in the later period, we are dealing with estimates, not actual counts. In the technical language of measurement theory, the early-period drug rates are assuredly not perfectly reliable, and the later-period rates must be even less so. The effect of unreliability of measurement on correlation coefficients is to produce precisely such "regression" effects as noted in the first sentence of this footnote.

The lower correlation between early- and late-period rates in Brooklyn is also of no special import. The variation in drug rates between health areas in Brooklyn is considerably less than in the other two boroughs, and, as will be explained in the next chapter, this is a condition that leads one to expect lower correlations. The lower variability obtains in both periods—.a point that also speaks for the consistency of the data in the two periods.

Finally, it should be acknowledged that statistically sophisticated readers may be inclined to challenge even the main point, on the basis of a statistical artifact known as "spurious index correlation" that sometimes arises in the correlation of rates and produces higher correlation coefficients than are warranted by the true relationships. The issue will be discussed in the next chapter. For the moment, suffice it to say that the possibility need occasion no concern in the present instance; there is no such effect. Given the indicated sources of error, the obtained correlations between the early- and later-period rates are impressively high.

1 Joseph L. Coyle, "The Illicit Narcotics Problem," New York Medicine, 14 (1958), 526-528,534-538.

2 In some places, however, what is called "internal possession" is also illegal. In such localities, a person may be arrested for "internal possession" if there is reason to believe that he has taken drugs, but the violation is still in the possession rather than in the use. Such a law invites many abuses and is often hotly debated even in law enforcement circles. There are also problems involved in the proof of "internal possession," including the use of a recently developed drug which neutralizes opium products in the body and can thereby precipitate withdrawal symptoms in an addict.

3 U. S. Treasury Department, Bureau of Narcotics, Prevention and Control of Narcotic Addiction (Washington, D. C.: 1960). Also, and most germane to the present discussion, C. Winick, "Maturing out of Narcotic Addiction," Bulletin on Narcotics, 14 (1962), 1-7.

4 A recent publication by Winick, "The 35 to 40 Age Dropoff." Proceedings, White House Conference on Narcotic and Drug Abuse (1962), gives the number of cases entered in the file in 1953 and 1954 as 16,725. As of December 31, 1959, 65 per cent of these had not been reported again—that is, a seven-year period for the 1953 cases and a six-year period for those added to the list in 1954. The number of 1955 entries is still missing. We do not know whether to attach any special significance to the missing number, but it is worth noting that Winick's interest in the paper cited, as in that previously cited, was in the 1955 series. On the assumption that the number of 1955 entries equaled the average of the 1953-1954 entries, 7,234 equals 85 per cent of the 1955 cases. On the assumption that the number of 1955 entries was less than 8,363 (as is likely on the basis of the argument in the next paragraph), the number of nonrepeaters would have to exceed 85 per cent of the 1955 cases.

5 It is sometimes asserted that anyone will become dependent if he gets a large enough dosage at sufficiently frequent intervals over a sufficiently long period of time. Such a statement is an extrapolation from experience and, although a good axiom, cannot, in its very nature, be proven without subjecting everyone to "large enough" dosages, etc. Obviously, if one accepts the axiom, then a person who has been taking drugs fairly regularly without developing dependence has not been taking enough with great enough frequency or has, perhaps, not been observed over a sufficiently long period of time. Associated with the concept of dependence is that of tolerance: as the body accommodates itself to the drug, it takes more of the drug to produce the same psychic and physiological effects. What has been said of dependence may presumably also be said of tolerance; there are undoubtedly individual differences in the rate at which tolerance develops, but the axiom that everyone would acquire tolerance from sufficiently frequent doses over a sufficiently long period seems a reasonable one. It does not follow, however, that tolerance and dependence develop at the same rate. Hence, it also does not follow that a person who develops tolerance will go on taking increasing doses; that will depend on what psychophysiological functions the drug serves. A person who takes a drug purely for sociability may conceivably be indifferent to the fact that it ceases to have any discernible effects. Moreover, there seem to be variable tolerance levels at which the drug can prevent withdrawal symptoms, but no increase in dosage can restore the desired psychological effects; the only way of restoring the latter is to go through withdrawal and start the process afresh. Addicts do not go on indefinitely increasing their intake.

6 Whether one could actually find people who have taken heroin in ordinary doses daily over an even shorter period and of whom the same could be said, is problematical. If they exist at all, experience would suggest that they are exceedingly rare.

7 A. R. Lindesmith, Opiate Addiction (Bloomington, Ind.: Principia Press, 1947).

8 H. S. Becker, "Becoming a Marijuana User," American Journal of Sociology, 59 (1953), 235-242.

9 A. Wikler, "On the Nature of Addiction and Habituation," British Journal of Addiction, 57 (1961), 73-79.

10 I. Chein, "Personality and Typology," Journal of Social Psychology, 18 (1943), 89-109; "The Awareness of Self and the Structure of the Ego," Psychological Review, 51 (1944), 304-314; "The Image of Man," Journal of Social Issues, 18 (1962), 1-35. A fuller development will be included in The Image of Man being prepared for publication by Basic Books, probably in 1964.

11 Some cigarette-smokers show physical symptoms, e.g., marked tremor, in response to deprivation. Such symptoms are, however, psychological in origin, the correlates of tension and anxiety. True physical withdrawal symptoms related to physiological dependence can be demonstrated in animals. The point does, however, raise an interesting issue: in any particular observed human withdrawal reaction, how much is psychogenic and how much physiogenic is generally indeterminate. In strict logic, therefore, the mere fact of withdrawal symptoms is not sufficient to establish the fact of physiological dependence. This, in turn, complicates the issue of the dosage-frequency-duration combination that will produce dependence in almost anyone.

12 Edwin M. Schur, Narcotic Addiction in Britain and America: The Impact of Public Policy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1962).

13 In the Police Department file for 1952-1958 (Coyle, op. cit.), 67 per cent of the cases came from Manhattan, 15 per cent from Brooklyn, 14 per cent from the Bronx, and 4 per cent from Queens. If there are any cases at all in Richmond, they come to less than .5 per cent. These figures, of course, include adult cases. For the 1949-1952 period, there is reason to believe that there were hardly any juvenile cases in Queens.

14 1949 thus marks what may be the beginning of a new period in narcotics use. We do not know to what extent the "natural history" of the adult user who turns to narcotics in his adult years is the same as that of the younger cases, although even in the 1920's and 1930's statistical studies had pointed out that the majority of adult addicts had started to use drugs in their adolescence or early adulthood. The ranks of the adult users certainly include a much larger proportion of innocently caused cases, both because adults are more likely to suffer from ailments that call for the use of opiates and because physicians have become more careful in their administration of these drugs and utilize, whenever possible, more recently developed, less addictive substitutes. There is also some reason to suspect that personal psychopathology currently plays a larger role in the initial flirtation with narcotics among adults than among adolescents. At any rate, for some time to come, increasing proportions of adult users will be individuals who started in their teens.

15 The reason for this strategy may be described as follows: If females and younger cases are not materially different in relevant aspects of their drug use from males in the sixteen-to-twenty age range, then, in excluding them from the study, we have sacrificed little but the greater precision contributed by a relatively small number of additional cases. If, on the other hand, there are materially relevant differences, including them obfuscates the picture for all. Why not study all groups separately? This is a question of the availability of resources. Additional analysis entails additional expense. Later in the book, we shall report on a small series of female cases, in addition to the statistics presented in this section.

16 We did not learn until shortly before the publication of Coyle's article (op. cit.) that the Police Department had started a file as of the beginning of 1952. Actual work on this file presumably did not start until some time after its opening date.

17 The drug involvement of girls aged sixteen to twenty and children below the age of sixteen was determined from the probation case-file of the Magistrates' Court Probation Department referring to cases appearing in Home Term, Girls' Term and Women's Court (prostitution), the Youth Council Bureau case file, municipal hospital records, and the docket books of Children's Court. These data were collected only for the first series, covering the period from January 1, 1949, to October 31, 1952. Unless otherwise specified, all findings mentioned in this chapter refer to males between sixteen and twenty-one years of age on the date that drug involvement was first officially discovered. Some of the cases in our 1949 series and to a lesser extent in the lists for each succeeding year may, of of course, have been known prior to 1949. "First officially discovered" and "new cases" should therefore be interpreted with this qualification in mind: "since January 1, 1949, they first came to public attention in the year . . ." The total number of such cases, dating back to before 1949, must, however, be quite small.

18 These figures may be compared to the Police Department figures for all cases as cited in footnote 13. When the latter are adjusted to the three-borough basis, they become: 69.8 per cent in Manhattan, 14.6 per cent in the Bronx, and 15.6 per cent in Brooklyn.

19 Not included in the above figures is a total of 344 girls (aged sixteen to twenty) with narcotics involvement who were known to the courts and hospitals during the period between January 1, 1949, and October 31, 1952. This is slightly more than one-fifth of the number of males appearing during the same period. Many of these cases appeared in the probation files of Women's Court and were prostitutes. The peak year for girls, as for boys, was 1951 in each borough. Similarly, a large majority of all girls with drug involvement lived in Manhattan, rather than in the Bronx or Brooklyn, at the time of their first narcotics-involved contact with the court or hospital.

In addition, a total of 130 children below the age of sixteen became known to the courts and hospitals during the forty-six—month period covered by our first series. Of these, 106 were boys and 24 girls, the proportion being between 4 and 5 to 1, as was true for the older juveniles. Again, the peak year for these younger children was 1951, and a large majority lived in Manhattan at the time they were discovered to be involved with drugs.

20 On the death of its physician, the Youth Council Bureau terminated its examinations of youngsters charged with a narcotics violation or suspected as users. Another factor in the relative "weakness" of our second series is that, over the years, Probation Department workers have probably become less diligent in sending in their special reports on narcotics involvement. This would be quite understandable, considering the enormous case load on these investigators and the fact that they were not continually reminded of the need for these special reports to be filled out whenever they discovered that an accused was known to be a drug-user.

The effect of both these factors is that our data for the later period are based almost completely on youngsters actually charged with a narcotics violation. This means that estimates for the later years must be, if anything, relative underestimates in comparison to our figures for the early period.

At a meeting of the Narcotics Committee of the Greater New York Community Council, Inspector Coyle stated that the Police Department list was growing at the rate of four to five thousand cases a year, closer to five than to four. He also stated that from 13 to 15 per cent were cases in the sixteenthrough-twenty age range. This would give about 650 new cases per year in this age range, and, allowing for girls and cases under sixteen, the figures agree fairly well with our own.

21 Of fifty cases at a state training school to which boys are sent after being processed at Elmira, selected by the authorities as nonusers, four admitted to regular use prior to their commitment and gave enough circumstantial details to our interviewers for the admission to be accepted at face value. This is 8 per cent and suggests a fairly large over-all number of undetected users.

22 Although Table II-2 does not give borough data, the predominance of heroin involvement also appears in each borough.

23 Since it is not possible to estimate yearly changes in the size of the base population, we shall have to satisfy ourselves with an over-all comparison of drug rates for the early period of data collection (1949-1952) with estimated rates for the later period (1952-1955). See Appendix A for a detailed description of the computation of drug rates.

24 Let it be here specified that, unless otherwise indicated, a "case" refers to a boy in the sixteen-to-twenty age range who is known to have been involved with narcotics. A given case is counted only once; that is, if the same boy has been involved in more than one offense, he is still counted as only one case.

25 See Appendix C for an explanation of the procedure.

26 For the benefit of readers unfamiliar with this statistic, a relatively simple explanation is given in Appendix C. This statistic is used extensively in the analysis that follows. In general, the statistic varies from plus 1 to minus 1. A correlation of plus 1 implies a perfectly consistent trend for one variable to increase with the other. A correlation of minus 1 implies a perfectly consistent inverse trend—as one variable goes up, the other goes down. A correlation of zero means that there is no trend—the average on one variable tends to remain the same as the other increases.

27 It should be emphasized that the sheer incidence of drug use, regardless of the context in which drugs are used, is not at issue. For example, if we were to investigate the socioeconomic correlates of drug use prior to passage of the Harrison Act, we would probably come up with a quite different picture. But, then, the behavior involved in taking drugs without medical prescription was doubtless also different. Opiates were used quite indiscriminately in proprietary medicines; users did not know what they were taking; they were not involved in illegal activity; the sociocultural factors encouraging and facilitating drug use were quite different; and so on. The question is whether we might not be in a period of radically changing drug use, with associated changes in the nature and meaning of the behavior involved and, consequently, whether we might not be in a period of changing correlates of drug use. It is with this question that the above text has been concerned. If there had been marked change in the distribution of drug use in the two periods, we would have to consider the possibility that, in some way, the nature of the behavior involved had changed. The analyses we report in the subsequent chapter would then become hardly more than a historical curiosity, rather than germane to a pressing contemporary problem.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|