6 Becoming an Addict

| Books - Narcotics Delinquency & Social Policy |

Drug Abuse

VI Becoming an Addict

In asking the boys to reconstruct the process of becoming involved with narcotics, we distinguished four stages: experimentation, occasional use, regular or habitual use, and efforts to break the habit.

A user may go through all these stages, but he may stop at any stage. There is reason to believe that there are significant differences among the four "types": those who experiment but do not repeat, those who use heroin occasionally but never become habituated, those who become regular users but succeed in their effort to break the habit, and those who are firmly "hooked." We shall follow the path of those who became addicts and note the critical stages at which some stopped and others went on.

The findings presented here are those of the interview study of users, delinquents, and controls and of the study of gangs.

Experimentation

At the time of our interview study in 1953, experimentation with heroin typically followed a period of smoking marijuana cigarettes; eighty-three of the ninety-six heroin-users who answered this question had smoked marijuana, forty of them regularly, before they began using heroin. In the street-gang study, however, it developed that there were may juvenile heroin-users not known to have started with marijuanavithe boys were introduced to marijuana at school, dances, or pardds and were usually given "cigarettes" by friends; the "reefers" were often passed around a group, like an Indian peace pipe. A few had their first smoke as early as age ten or eleven, but the most common age was fifteen.

Marijuana is undoubtedly in much more common use than heroin. For instance, 15 per cent of the controls had had some experience with marijuana. Even so, we may take it as axiomatic that at least the regular smoking of marijuana is, as a rule, associated with participation of the smoker in a deviant subgroup of peers.' On this basis and owing to the common pattern of starting drug use with marijuana, we would expect that the first use of heroin was, for most boys in our sample, an experience which accorded with the general atmosphere of their social groups; at any rate, it was not likely to be a shock. This was, indeed, the case.

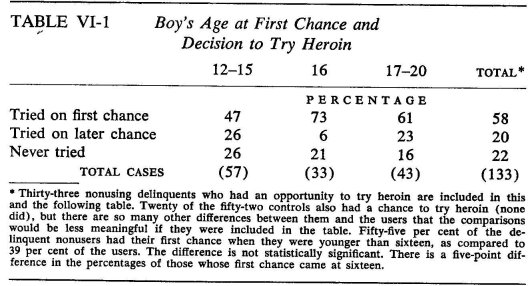

Most of the users had heard about heroin for some time before they actually had a chance to try it, usually at the age of about fifteen; by that age, most of them had also seen someone inject or snort heroin. In most cases, the first chance to actually try the drug came when they were about sixteen or seventeen years old, but a sizable proportion were much younger at the time; a fifth were fourteen or less.2

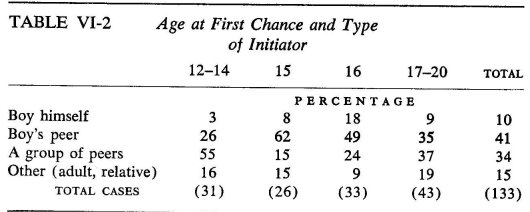

The first opportunitiy came about in a simple, casual way. About a third of the boys were offered a "shot" or a "snort" by a youthful friend, and, in about another third, the opportunity developed in a group setting and at the initiative of the group. Very few actively sought the first opportunity, and a few others were offered drugs by members of their families or unrelated adults. In most cases, the heroin was obtained easily and without cost; in only 10 per cent of the cases did the boy pay for his first dose. The decision to try drugs and the transaction usually took place on the street, on a roof, in a cellar, in a private house, or often at or before a dance or some other large party. In a few cases, the event took place at school; in another few, in a bar, a poolroom, or some other public establishment. The "second chance," for those who did not take the first offer, occurred under similar circumstances. Typical situations of the first try are described in the boys' own words.

It was raining, and I was tired. I was standing in a doorway when this friend of mine came by. He said, "Want a pick-up?" I said "Sure," so we popped.

I was at a party. Everybody was having a good time. I wanted to be one of the crowd. I thought, if it didn't hurt them it wouldn't hurt me. That started the ball rolling. They were sniffing it that time. Two or three pulled out a few caps; said, "Here, if you want to, try." I accepted. They weren't trying to addict me; they just gave it to me.

It was in school. At that time, all the boys were using it. A friend offered me some. Said it was something different. He had just started using it himself, and he wanted me to try.

Other accounts of the first experience with heroin convey more clearly the easy and "natural" manner in which the mood of the social situation produced or was hospitable to the suggestion to try heroin.

One of the seamen I knew, knew I smoked reefers and thought I ought to try heroin sometime. Hanging around the block, there were a couple of fellows who were new around the block. They were going down to the cellar to snort the stuff. They asked me to join them. I was a little leery at first, but then I went with them. They offered me a little, and I snorted it.

Some of us was in a car. We was going to town one night, so one of the guys said, "Let's take off [use drugs] before we start." I said, "Not me; I don't want any." But one of the guys owed me $2, so he said: "Come on. I'll give you four pills, and we'll call it even." So I tried. That was just skin-popping. The next day I was with this same guy, and he was mainlining. Wanted me to try it. I tried two pills at once that time.

I was going down town with a guy. He wanted to borrow $1.25. (He had money, but no change.) He went and got a bag, or a deck. It was nice stuff. Would have cost anybody else $12. He asked if I wanted some. I said no, but, being as I had put some money into it, I changed my mind and sniffed some.

Bunch of fellows my age were down on the corner. Someone said, "Let's try some." No one knew where to buy it then, but we made a contact. So we went up on the roof and snorted.

At a party. A fellow had some. He was one of my friends, and I figured he was straight. He suggested it, so we snorted.

I was on the corner one night alone. Fellows came up. Some friends of mine said, "Let's go to a party." I said, "Hell, no." One of them said that a fellow at the party had some heroin. So I was curious, and I went along. We snorted.

There were three of us. Someone said, "Let's buy some horse." One of them went and got some works. So I skin-popped.

The social situation in which the suggestion was made to try heroin was free from any overt conflict or constraining pressure. Unless the boy had his own doubts about taking the drug, it was not likely that some other member of the group would demur or question the suggestion. The transition from knowing about heroin and its "pickup" attributes to becoming familiar with the mechanics of buying a "deck" to knowing heroin-users more-or-less casually to personal participation —this transition appears smooth and natural in the types of social group and situation described by most of our sample of users.

The absence of constraint in the situation was matched by absence of inner restraints; three-quarters of those who eventually became addicted tried heroin at their first opportunity.

How representative are these experiments with heroin of the exposure to heroin among all adolescent boys in the high-drug-use areas? The answer is, not at all. The situations described above are typical only of some subgroups in the neighborhood; the easy acceptance of the drug is typical only of some boys.

Even though knowledge of heroin is widespread—most of the nonusers had heard about it by the time they were fifteen or sixteen years old—there are subgroups where the suggestion and the opportunity to try drugs never arise; there are youths who refuse to try the drug even when it is offered to them.

Of the fifty nonusing delinquents, two-thirds had had an opportunity to try, but only four did—not continuing, of course. Of the controls, 40 per cent had a chance to try heroin, but none of them did. The first opportunity came when they were in their fifteenth to seventeenth year.

WHY DO THEY REFUSE TO TRY?

Several easily ascertainable factors seem to be related to the readiness to try heroin when the opportunity arises: the boy's age, some deterrent information on the drug, and, less clearly, his interpretation of the attitudes of significant adults toward drug use.

Age. Among the delinquents and users, sixteen seems to be the age most susceptible to experimentation with drugs. For one thing, boys who get their first chance to try drugs at this age are more likely to try on this occasion than boys who are either younger or older at the time of first opportunity. Those who got their first chance when they were under sixteen were least likely to try immediately.

Further, boys who got their first chance at the age of fifteen or sixteen typically reported that this happened on the initiative of a friend in a face-to-face situation, whereas most of the boys who were either younger or older at the time typically reported that they took the drug in a group. The first exposure on the boy's own initiative was also most frequent among the sixteen-year-olds.

Finally, the balance of individuals with favorable, as compared to those with unfavorable, reactions to the first try was negative (i.e., there were more with unfavorable than with favorable reactions) for those who had their first try at the age of thirteen, but this balance changes rapidly so that it is only slightly negative at fifteen and becomes positive at sixteen. At sixteen, there are more boys with definite positive than with definite negative reactions. By age seventeen, this excess increases to 50 per cent, but for the eighteen-year-olds and over it drops very markedly.3

Thus it appears that, among those given the opportunity, the sixteen- and seventeen-year-old boy is more likely to try heroin on the first chance than either the younger or the older boy, is more likely even to initiate the first try, and is more likely to experience a positive reaction to his first intake of heroin. One might venture to say that there is a lowered resistance to the unique temptation and unique satisfactions that heroin offers at that age. It is not difficult to speculate on the reasons. Sixteen is the age of transition from childhood to adulthood. It is the minimal legal age for leaving school and for obtaining working papers. And, in general, it is perceived in our society as an age when the youth is no longer a child. One can assume that a youth who feels inadequate and insecure, whose self-confidence and self-esteem are low, will experience the demands for maturity that accompany his sixteenth year with increased discomfort. When the need for surcease, for peace of mind, for the quelling of self-doubt is intensely felt, one expects that whatever resistances the youth has to experimentation will become less effective.

Deterrent Information. The hope is often expressed that effective information on the dangers of addiction may act as a deterrent to drug use. Some of the statements made by the users we interviewed supported such hopes. One of them said:

If I had known that it would blow up everything. . . . Those kids just passed it around like it was nothing. Everybody was taking it, just sniffing it, didn't know anything about it. If I had known about it, I never would have tried the junk. I tried it because I didn't know anything about it. No one in my neighborhood knows anything about it. That's what they need—education—so that kids know what the stuff can do. It can blow everything up in your face.

We asked the boys what they had ever learned which might make them "hesitate and think twice" before taking a drug and how old they were when they learned each item of information that they mentioned. We then coded the boys' answers separately for "learned deterrent information before critical age" and "after." Hardly any of the users (only 17 per cent) said that they learned anything cautionary about drugs "before," whereas most delinquent nonusers (79 per cent) said that they did so before they were sixteen (which, as has been mentioned, corresponds to the median critical age for the users).

Although much of this difference might be discounted because of retrospective falsification by the users of events which took place prior to their use of drugs, the difference is too great to be entirely dismissed. It is consistent with the view that such information does, in fact, deter at least some youths. It is, however, also consistent with the possibility that the kinds of boys who become users are more resistant (emotionally and/or intellectually) to such information and with the possibility that the acquisition of such information is a more-or-less incidental correlate of other factors that differentiate the two groups.

What was the nature of the deterrent information? The main thing, mentioned by three-fourths of all delinquent nonusers as well as users, was that drugs were bad for health or dangerous to life.

It makes your veins collapse, gives you yellow jaundice or abscesses, or you get an overdose and die.

It will mess you up physically. You get sick, your eyes keep running, you lose a lot of weight.

You might kick [die] from using too much. Don't take a shot from your friend. He'll give you a hot shot; try to kill you and take it all for himself. I saw it happen to a girl; she died.

Second in frequency of mention (60 per cent) is the fact that the cost of drugs forces users to resort to illegal activities.

When you need drugs, it'll make you go out and steal. Everytime you get a dollar, you'll use it or set it aside until you do need it for drugs.

Makes you do illegal things; makes you steal and peddle.

Finally, about half the users said that they had learned that the drug habit leads to deterioration of character.

Can't get nowhere. Anywhere you go, you go down. Can't hold a job, can't keep money.

You just lay around and do nothing. It changes your character, makes you snobbish, irritable, untidy.

It makes you cranky. Sometimes you lose friends. You lose interest in everything. You like nothing but drugs.

It changes you completely; you become dishonest, like stealing from your mother. I never got to that; I broke in and took things. I know when I was running the dice game, you could trust people and leave the game, but with junkies, you have to watch them every minute.

This information was supposedly obtained predominantly from "own observation" or "own experience" and from friends. Only a few said that they gained information from reading, and a negligible number, from adults (parents, teachers, and the like). The delinquent nonusers had acquired the same type of deterrent information and from the same sources (except, of course, own experience).

Social Pressure. Most of the boys we interviewed (from 60 to 80 per cent in each of the four groups) did have, at the critical age, some friends whose opinion "meant the most" to them. But when we asked what these friends felt about heroin-, marijuana-, and drug-users, only the control group gave unequivocal answers: nearly all the friends who mattered to them had negative feelings about drugs and users. The users and delinquent nonusers claimed mostly that they did not know what their friends' feelings about drugs had been. Of the twenty-eight users who "knew," eight said that their friends' feelings about the drugs had been positive or accepting, and sixteen said, negative. Only one of the seven delinquent nonusers who could answer this question associated positive feelings with his friends, and the other six attributed negative attitudes to their friends. The number of answers is, of course, too small to bear any weight as evidence, even though the trend is in the expected direction.

The data are even less discriminating with respect to the one adult person whom the boy would most like to think well of him. Almost all boys said that there was such an adult in their lives at the critical age. In the control group, this was usually the father or both parents; in the other three groups, it was usually the mother.4 The reported attitude of this adult to heroin and its users had been overwhelmingly negative in all four groups we interviewed, and most boys knew or felt that they could surmise this person's attitude.5

Let us return now to those who do try the drug. Why are some of the youths capable of "playing around with" heroin, sometimes for long stretches of time, but do not become habituated, whereas others proceed rather quickly to incontinent use and habituation?

OCCASIONAL USE

Most of the users on the first try "snorted" (sniffed) the drug. Their reactions ranged from extreme euphoria to nausea, feeling sick, feeling "bad," or depression. Nearly half experienced definitely pleasant reactions, and about a third, negative reactions. Some reported mixed sensations or no sensation at all, explaining that, "If you don't know about it, you don't know how the kick goes."

These are descriptions of the positive feeling after the first try:

It gave me like a sense of peace of mind. Nothing bothered me; it felt good.

Felt above everyone else—ready for Freddie—great.

I felt all right and more sure of myself.

I got real sleepy. I went in to lay on the bed.. . . I thought, this is for me! And I never missed a day since, until now.

I felt I always wanted to feel the same way as I felt then.

I felt above everything. I felt I knew everything. I talked to people about interesting things.

Felt like heat was coming through my body and head. It made me forget all things. Felt like nobody existed but me, like I was by myself.

It is, of course, difficult to assess the truthfulness of these accounts. Even with best intentions, the users, at the time of the interview, might have retrospectively endowed their first experience, which took place two to three years before, with the glow of the "high" feeling they later experienced. But there is no reason otherwise to doubt their reports of euphoric reaction on first try. Laboratory experiments° have produced positive reactions to first intake of opiates. And, although some users claimed that they felt nothing until they knew what feeling to expect, this need not be universa1.7

Reaction to the first trial helped to determine the timing of subsequent use. Two-thirds of the boys whose reactions were favorable continued immediately, compared to only two-fifths of the boys whose first reaction was unfavorable. The remainder did not resume until a somewhat later period. In any event, 90 per cent of the users were using regularly within a year of the first tria1,8 the rest within two years.

FROM OCCASIONAL TO REGULAR USE

The distinction between occasional or weekend use of heroin and regular use of at least one intake daily is basic. For one thing, occasional use does not necessitate the urgent quest for contacts and money to procure the drug. For another, it does not necessarily precipitate the changes in interests, mood, and leisure activities which, as we shall see, characterize the regular user's life. Rather, occasional intake of heroin at parties, on week ends, or at times of feeling low, serve a supportive and pleasurable function as a rule, with no negative side effects; this is sometimes referred to as "the honeymoon stage."

What makes for increased frequency and regularity of intake? The sheer addictive properties of heroin are certainly not sufficient to account for the change, for heroin has no universal addictive impact, and certainly not if taken in intervals of more than a day. 9 Furthermore, there is some evidence that many youths go on using heroin on a moreor-less irregular basis—e.g., week-end and party use—for several years and eventually stop altogether. In our study of heroin use in gangs, we found that, of the eighty current heroin-users, less than half were using daily or more often and that fourteen boys who had used heroin in the past had stopped completely.

This is the one point in our findings to which at least one expert has reacted with total incredulity. He has, on numerous occasions, stated that, in his experience, no teen-ager has ever started to use heroin without going the whole way and that, though there are regular adult users wh6 have been known to stop, no adolescent has, in his experience, ever been known to do so. We referred to the existence of such a point of contradiction in the first part of Chapter V and promised to return to it. The contradiction may be accounted for in large measure by the nature of the agency this expert—modestly, he insists that there are no experts in the field of drug addiction—has created and directs. It is a helping agency; the clients come to it because they are in trouble owing to their involvement with narcotics. Boys who do not get into trouble because of narcotics have no reason to come to the agency. The boys who do come have a strong need to confirm the belief in the irreversibility of the path, since it not only gives them an alibi for continuing use, but also helps to maintain their self-esteem (and, incidentally, makes it more difficult to treat them) by its implication that, basically, they are no different from anyone else. In other words, the testimony of the boys who do come to the agency would be affected by a strong motivation to agree with the belief in irreversibility, along with solemn promises to try to stop.

In part, the contradiction can be accounted for by how one reads the agency's data. One of the cases, for instance, with which the agency has dealt for many years has been known to abstain voluntarily for relatively long periods of time. He always comes back, however. If one places the emphasis on the relapses, this case is consistent with the hypothesis of irreversibility. If one considers the long periods of voluntary abstention, it definitely is not.

We do not know how many other such cases have come to the attention of this agency. In principle, however, we would expect at least two varieties, not counting the varieties that do not come to the agency. The first is exemplified by the case just mentioned. This young man abstains successfully as long as life is proceeding smoothly for him, but he quickly relapses under conditions of stress. We are, of course, aware that his own self-destructive needs may help to generate that stress. This does not gainsay the fact that there are conditions under whch he can voluntarily abstain. It is consistent with the belief that there is no sharp dividing line between the nonaddicted user and the hopelessly chronic addict; and it is consistent with the fact that there do not seem to be any sharp discontinuities in the distribution of individual differences, no matter which dimension of individual differences is under consideration. Even in the anatomical differentiation of the sexes, one finds intermediate cases.

In Chapter II, we described four varieties of addicts, two of which we described as truly addicted; the essential criterion is that such cases involve craving. The patient described in the preceding paragraph meets this criterion even though his craving for the drug is not continuous. When a person craves a drug, he needs it as a means of alleviating the distress of frustration, anxiety, or pain; it seems clear that this patient does rely on the psychopharmacological effects of the drug as a coping mechanism. On the assumption that his periods of abstention are not completely free of stress, this case does emphasize the fact that craving is not an all-or-none phenomenon, that is, that even true addicts differ in the readiness with which they fall back on this coping mechanism. Parallels are readily found in phenomena related to drug addiction. For instance, alcoholics, thumb-suckers, and overeaters differ in how much stress they can take before they, respectively, feel impelled to drink themselves into oblivion, take their thumbs into their mouths, or "narcotize" themselves with food.

The second variety of recurrent user who can voluntarily abstain under certain conditions belongs, to our minds, in the ranks of users who are not truly addicted. (We make no reference in the present discussion to the first of the not-truly-addicted types discussed in Chapter II—total personal involvement, but without craving—because we are not certain whether there are intermittent users of this type. It is conceivable, however, that some individuals habitually fall back on involvement with narcotics and with the drug-using subculture as a means of filling temporary voids in their lives.) In principle, we would expect that there are many such cases. Such a person is never truly "hooked," although he may go through periods of physiological dependence and experience the withdrawal syndrome. Even after hospitalization or imprisonment, he goes back to drugs, sooner or later, because he returns to the same circumstances in which he succumbed to the impulse to experiment in the first place. These are cases of recurrent "infection," not of continuing addiction. If one does not distinguish between a recurrently induced impulse to indulge and a more-or-less chronic craving for the intoxicated state, such cases would reinforce a belief in the inevitability of the transition from experimentation to addiction.

Again, in terms of the principle of relative continuity in the distribution of individual differences, we would expect that there are many cases of mixed type of the two varieties we have just distinguished, that is, individuals whose craving varies more-or-less consistently with variations in the stress of their situations, whose impulses to indulge are more-orless strongly induced by their environment, and whose thresholds of stress and resistance to craving are lowered by the effects of indulgence.

At any rate, it is clear that not all youths who experiment do go on. What, then, makes some youths who have experimented with heroin switch from occasional to frequent, regular use? We formulate this question thus—in terms of incontinent use rather than in those of addiction—because, as just noted, the category of regular users is more inclusive than the category of addicts. Only some of the regular users will go on to become full-blown addicts. In other words, from the viewpoint of causation, there is a logically, if not chronologically, intervening step between experimentation and addiction, and this is the step that we now explore.

Let us distinguish between the force of the growing appetite and the capacity to maintain control over it. Let us also assume that those who develop an increasing appetite are those for whom the effects of the drug are especially gratifying: they meet some strong need. And let us assume that a normal response to the awareness of a strange new impulse—especially one that is commonly known to be dangerous—is not to indulge but to try to control it, to hold it back.

It would follow that those who proceed from experimentation to regular use are either those who experience an exceptionally strong need for the effects of narcotics or those who have little wish or capacity to control the impulses. We consider the issues of need and control in later chapters. For the moment, however, let us note that the need for support may be intensified by objectively greater environmental stress at the time of experimentation. In the preceding chapter, some evidence was presented suggesting that users had experienced, at the time of onset of regular heroin use, some stress in their personal lives or family environment. There were indications that the users came from families that were less cohesive than those of their nonusing peers. There were indications that the users were thrust prematurely into adult roles. Many of them (about a fourth, compared to only one or two controls) experienced some radical change in their lives during the critical year—shift in family occupation, move to another neighborhood, and the like—which may have created special difficulties.

In the following chapter, we shall see that many gang members turn to narcotics when the gang is beginning to break up, withdrawing a feeling of solidarity and of belonging that may serve to make up for the failures of the home. We shall note, too, that this point in the life of the gang comes when the other boys are becoming seriously concerned with settling down to adult responsibilities, selecting a permanent career and a permanent mate; in other words, at a point where it becomes increasingly difficult to pretend that one is living up to an adult role simply because one does not have to account for oneself to parents and because one is earning the money for immediate needs in odd or dead-end jobs. This is the point at which many are confronted by the fact that they are not really ready for adulthood.

In other words, regular use comes at a point when, whatever the intensity of certain needs and whatever the vigor of the inner control system, most of the boys axe in a particularly weakened state because they are trying to cope with exceptional stress.

Life Style of Habitual Users

Let us now turn to the youth who, after a year or two of occasional use of heroin, finds himself relying on regular (at least once-a-day) doses of the drug to stand off states of intense misery. This sets what is often called the "frantic-junkie" stage. With the realization of constant need for heroin and anticipation of the depression or even the pain of withdrawal should he fail to obtain a "deck," comes the intense, continuous preoccupation with the means of obtaining the drug and the necessary money. This preoccupation becomes a central motive in the young addict's life, and it colors his behavior, interests, values, relation to his family and friends—in short, his whole life style.

Once regularly on the drug, most of the one hundred users we interviewed took at least one dose daily; two-thirds, two a day or more.

Almost all the regular users "mainlined"; twelve "sniffed," three "skin-popped," and one, reluctant to "skin-pop" and in order to avoid nasal irritation, sprinkled heroin on his food. Half the users spent more than $30 weekly on the drug; one-third spent between $20 and $30.10 Since most of them were not regularly employed, the necessity to procure the money became one important factor in their lives.

CHANGES IN MOOD

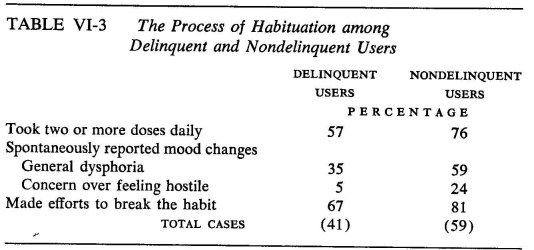

Another change the users reported was in mood and "character." Some of the changes in mood varied, depending on whether they were "on" the drug, "off," or in search of "a fix." The question we asked was: "Tell me something about your life after you started taking drugs. . . ." Only twelve of the one hundred users spontaneously mentioned positive changes, apparently referring to their "on-drug" personality: greater social poise, "smoother" manners, ease of social interaction. Even fewer said that their over-all mood had become a happier one. Most, however, spoke of their "off-drug" self. Half spontaneously reported general dysphoria—"feeling cranky and mean all the time" was the most common response. Some noticed an increase in aggressiveness —"seems like I got more heart to go out and hurt people." About one-fifth mentioned constant worry about the habit as a specific source of unhappiness. Whether they were aware of changes in their character or not, the actual off-drug mood of the habitual users was depressed, pessimistic, cynical.

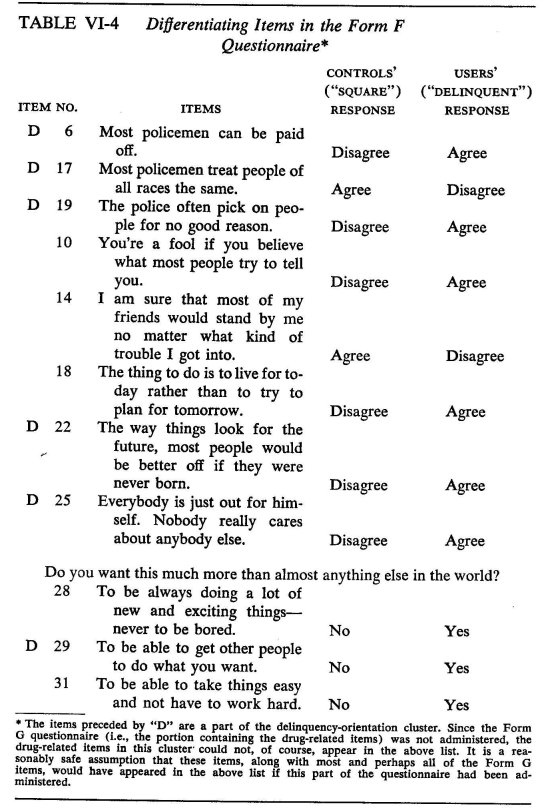

In their general values and attitudes, the habitual users were strikingly identified with the delinquency-orientation cluster described in Chapter IV. We administered the Form F questionnaire to a group of twenty-nine Riverside patients (most of whom may be safely assumed to be nondelinquent users) and compared their answers to those of the controls. On eleven of the forty attitude-value items, the Riverside group was (1) significantly different from the control group; and (2) the modal response of each group on a given item was the opposite of the modal response of the other group (i.e., if the majority of the users said "yes," the majority of the controls said "no," and vice versa). Six of these items are part of the delinquency-orientation cluster and reflect an attitude of futility, suspicion, anomie.

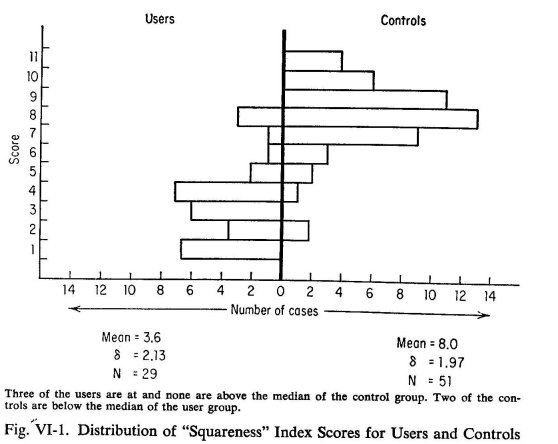

Table VI-4 shows the eleven items and the responses of controls and users. Every boy was scored on the number of "square" responses he gave, the actual range from zero to 11. As would be expected from the manner in which these items were selected, the users were very low on the "square" index, the control group very high.

CHANGES IN ACTIVITIES

Changes in the habitual users' activities reflect their mood and attitudes. Nearly half the one hundred users spontaneously reported loss of vitality—laziness, drowsiness, apathy, loss of appetite, sexual impotence. A few mentioned loss of interest in social interaction and a wish to be left alone. Some reported becoming careless about their appearance. There were corresponding changes in their leisure activities. Whereas more than a third spontaneously reported active sports as "the thing they did most often" with friends before they started using drugs, active sports were mentioned by only four of the one hundred users as a major activity after the onset of drug use, and some mentioned constant preoccupation with drugs as their main "leisure activity." Eighty per cent said that they "goofed more time away" after they started taking drugs.

Another evidence of their general detachment from life was the high proportion of users (two-thirds) who, in answer to probing, said that they "gave up responsibilities, such as quitting a regular job, quitting school, and the like." Only one-third said that they took on such new responsibilities as getting married, fathering a baby, taking a higher type job, and the like. We know, however, from clinical studies, that taking on new responsibilities is not equivalent, for a juvenile user, to carrying them on with a sense of responsibility; their marriages (and, among girls, pregnancies) are, as a rule, irresponsible ventures. Four-fifths of the one hundred juvenile users we interviewed said, in answer to probing, that they "started doing things against the law."

In our study of delinquent gangs, reports of Youth Board group workers revealed a similar change in interests and activities of users and nonusing members of the gangs. Fewer users tend to participate in inter-gang warfare ("rumbles"), dances, house parties, joint trips to movies or sporting events, and active sports. On the other hand, more of them participate in gang-organized robbery and burglary."

The association of drug use with crime for profit has been demonstrated also in other ways, both in New York and in Chicago. In New York City, the proportion of delinquencies likely to result in financial gain (e.g., robbery, jostling, burglary, larceny, procuring, unlawful entry) was substantially greater in areas of high drug use than in those of low or no drug use. Offences against persons and nonprofit rule-breaking (e.g., rape, assault, disorderly conduct, auto theft) were less preyalent.12 Similarly, a comparison of offenses committed in 1951 by adult and juvenile drug-users handled by the Narcotics Bureau in Chicago and the population handled by the Chicago Police Department revealed that "the number of arrests for non-violent, property crimes was proportionately higher among addicts. In contrast, however, the number of arrests of addicts for violent offenses against the person, such as rape and aggravated assault, was only a fraction of the proportion constituted by such arrests among the population at large."13

The evidence is thus clear that the user, juvenile or adult, engages in the illegal activities in which he does become involved, not for "pleasure" or because of any basic depravity, but mainly because he needs the cash to meet the high cost of black market drugs. This is not to say that the drug-user would typically be a law-abiding citizen if not for his involvement with drugs, but that drug use tends to channel illegal activity along income-producing lines. But the necessity for this type of criminality becomes an important determinant of the drug-user's life style and of his associations.

Most users break away from old friends and make new ones. About three in five of the one hundred users we interviewed admitted that they had broken away from some of their friends or other intimate associations, and four in five said that they had made new friends. We did not study the nature of these new friendships. However, from other evidence we believe that the new friends were more commonly engaged in delinquency and drug use than were the old friends. Since juveniles, as a rule, commit delinquent acts in groups, the juvenile user is perforce pushed into close association with those delinquent gangs which engage in delinquency for profit and must perforce sever his associations with gangs or individuals who have other interests. Our study of heroin use in gangs gave clear evidence that this process does, indeed, take place.

Efforts to Break the Habit

It is difficult to assess the relative importance of the various types of pressures and to discern the most important motive for making an effort to "lay off" the drug temporarily or to break the habit. When we asked the seventy-six of the one hundred users who had made at least one such effort to tell us "Why [did you] lay off heroin for a while?" we got more than two hundred answers, an average of almost three reasons by each user. Four reasons were spontaneously mentioned most often, each by about one-third of the boys: they felt it was wrong, they worried about the money they had to get, the heroin made them feel "sick," and they worried about becoming really "hooked." On probing, the first two reasons were again mentioned most frequently, and, in addition, the boys admitted a fear of being arrested and that "somebody worked on [them] to lay off." Other fears mentioned by a smaller number of boys were of "losing my mind"; of becoming sexually impotent; of being killed by an overdose or an "air bubble" or of being poisoned by someone; and concern over the changes in their behavior and character, such as loss of interest in activities, inability to hold a job, inability to "get along with people," and the like. One reason given by many nondelinquent users and almost never by delinquent users involved perception of deterioration of character—laziness, withdrawal, aggressiveness.

I wasn't myself. I became arrogant, sarcastic, wanted to better myself. Didn't want people to think my family wasn't raising me right. Didn't want to be around a bunch of lousy guys.

I just felt myself going down, losing interest in everything. I figured it was bad for my health. Then, too, I started pawning clothes and stealing.

Findings from other studies give independent evidence that these reasons are probably genuine, at least on a conscious level. Clinical evidence indicates that their social relations with nonusing peers and their family relations become even more strained than before the onset of drug use, that some of them really feel guilty about drug use, and that heroin makes some "sick."4 Fears of impotence and of being killed by an overdose are reasonable in view of the properties of the drug and the variability of the adulterants and of the concentration of heroin in the "decks"; so is concern over loss of vitality. The urgent queq for money is evident in the increased criminal activity described above. Fear of arrest is also realistic.

Our study of heroin use in gangs also produced evidence that the users were worried about their addiction. About half of the ninety-four users expressed concern about their habit to their group worker.

But the road from concern and worry to success in abstaining is not an easy one. Three-fourths of the one hundred users we interviewed said that they had made at least one effort to stop using heroin; half had made more than one effort. Of the ninety-four users in the gangs we studied, almost three in five were known to have made some effort to cut down or stop using altogether. At the time of the study, only fourteen had succeeded, and an additional twenty had reduced their intake.

WHAT ARE THE EFFORTS?

Some "efforts" consisted merely of good resolutions. Some, especially among the members of gangs, consisted of the avoidance of contacts with other users and increased contacts with the Youth Board worker and with those members who did not use drugs. In this, some users received warm support from their nonusing friends who stayed close to them and, in an earnest effort to be helpful, treated them to food, wine, or marijuana.

Two-fifths of the one hundred users reported that they had been urged, mostly by parents, to "lay off." Yet the actual help proferred by parents does not appear impressive. In about three-fourths of the seventy-one cases on which information is available, parents did nothing at all. If they tried to do something, their action was likely to be authoritarian in approach; they ordered the boy out of the house, took him forcibly to court, beat him, rather than undertaking some program of joint action with the boy. In general, parents seemed little aware of anything effective that could be done to help their children help themselves»

Few who wished to break the habit sought medical help. Of the ninety-four users in the gangs we studied, only one-fifth received any medical attention, and most of those not voluntarily but following an overdose or arrest. Even at Riverside Hospital, although many of the patients are there "voluntarily," very few are voluntary in more than a technical sense.

WHO MAKES THE EFFORT?

Several factors seem to be related to the efforts made by the users to free themselves from the habit: family cohesion, the attitude of important others toward drugs, age at first try, and, in gangs, the composition of gang membership.

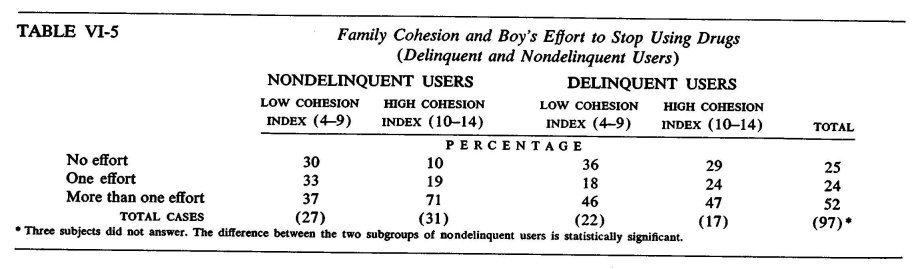

Family Cohesion. The more cohesive the young user's family, the more likely he was to make frequent efforts to break the habit. However, this was so only among the nondelinquent users. Seventy-one per cent of those nondelinquent users who came from the more cohesive families made more than one effort to lay off drugs, compared to only 37 per cent of those from the less cohesive families. Delinquent users showed no difference in this respect.

Attitudes of Important Others. Another factor in the boys' efforts to discontinue drug use was the general attitude toward drugs of the adult whom they identified as the one whose opinion was the most important to them. Of the fifty-eight cases who described the attitude toward drugs of this "most important person" as extremely negative, three-fourths made one or more efforts to "lay off"; of the forty-six cases where this adult's attitude was described as less extreme or indeterminate, only two-thirds made such efforts. Also, the attitude toward drugs of the boy's peers was related to his efforts to discontinue; the more negative it was, the greater the chance that the boy would make efforts to stop using drugs. One must, of course, note that this information is not fully trustworthy; it may be that boys who tried to stop were readier to admit to the negative attitudes of significant others, and they may have been readier to accept as significant others individuals whose attitudes to drug use were negative.

The Role of the Gang. What we have learned about the patterns of drug use in gangs confirms the importance of the gang in controlling drug use among its members. In the popular mind, the delinquent gang is a source of pressure for incontinent use of drugs. This is far from true. Experimentation with drugs may be a part of the delinquent culture, but habituation is not. Group workers in our gang study reported many instances where gang members tried to influence, and exerted strong pressure on, using members to cut down or discontinue the use of heroin. Pressures not to use heroin were mentioned by several workers as permeating the whole gang. Even users were more likely to behave in this manner toward their fellow members than to try to influence them to use. This finding held for every gang with more than one or two users. Some of the accounts of such influences against heroin use are illustrative.16

In one high-use gang, very permissive toward drug use and with a possible recent increase, the worker reported: "Shorty [a drug pusher] began telling the nonusers about the evils of drug use. . . . He won't sell them horse, only pot."

In another high-use gang, more active efforts were made.

One key figure known to me stated that he had held a series of informal talks with one of the club members who began to use drugs and as a result of these talks got him off the kick.

Art, an old user and respected by Frank, took it upon himself to talk periodically with Frank, pointing out the disadvantage of drug usage, and persuaded Frank to drop the kick.

In one high-use gang, paradoxically quite hostile toward use and unsympathetic toward users, the following is reported:

Allie has spoken to Paul individually, telling him that he was much better off before he used drugs; he talked about how much better off he was mentally and physically. Allie sought to get the worker to assist Paul also.

One of the most interesting situations is reported in a very high-use gang with little drug permissiveness and much recent decrease in drug use.

Members try to get others to cut down use of horse, especially when one member uses a great deal. This takes the form of individuals' or cliques' warning the fellow to get off the stuff, cut down, take more pot. The fear is that the fellow will take an overdose or get really sick. Sometimes the procedure of getting someone to take less stuff takes the form of treating to food or treating to pot.

In one gang, the group attitude toward the sole user was so hostile that he went to other gangs for drug activity; he is now off drugs.

Age. We have already discussed the importance of age as a factor in experimentation and habituation, and we discussed the greatly increased vulnerability to the effects of heroin at the ages of sixteen and seventeen. We also found that those youths who started using heroin regularly at the age of sixteen subsequently made less effort at stopping than those who had begun at either a younger or older age.17

HOW SUCCESSFUL ARE THE EFFORTS?18

Some of the efforts were apparently successful. Of the fifty-three users in gangs who made efforts to discontinue use, fourteen had stopped using, and twenty had, in the judgment of the group workers, decreased their intake at the time of our study. It is important to stress that not all of those fourteen who stopped completely were merely beginners or week-end users; seven had been taking at least one dose of heroin daily for some time before they "broke the habit."

Nineteen gang users received medical attention in connection with their drug involvement; however, none of these stopped using the drug, although four have decreased their intake.

Thus, while heroin addiction is not necessarily permanent, it is not easy for many to give it up, nor do most young users earnestly attempt to do so.

The great majority who continue with their habit almost automatically enter the category of "junkies" known to the police. At this point, the users have become young adults living in the criminal world. Since all our studies were focused on users under twenty-one years old, we do not have a complete picture of the young adult user. Apparently they continue their drug-centered existence and periodically appear in courts, jails, and hospitals.a

Summary

Most youths in high-drug-use areas had heard of heroin at the time they were fifteen years old, and some had seen others take the drug. We have no evidence of group pressure to experiment with drugs. The first try of heroin was a casual, social experience with peers.

The readiness to try the drug appears related to age; those who were sixteen and seventeen were especially susceptible. Descriptions of positive reactions to the first try suggest a sense of surcease, of the lifting of a weight, of peace and rising self-confidence. Most of the boys who had this positive reaction continued to use heroin as an occasional relief and prop. The others did not try again or tried only after some time.

Of those who became regular users, most went on taking heroin occasionally for a year or two. Once a habitual user of heroin, the youth underwent a drastic change in his life style. He became involved in criminal activities to obtain the drug and to procure the money he needed for it. His leisure pursuits became money-getting ones. His mood varied; when on drugs, he was "smoother" in social interactions, more poised. When off drugs, he felt "mean and cranky," worried, depressed, helpless, incompetent, hopeless, apathetic, lazy, indifferent.

Many quit school, gave up jobs, lost contact with old friends. They "goofed their time away."

Fear of arrest, worry about the habit, and a sense of guilt and shame prompted most of them to make some effort to break the habit. Those nondefinquent users who came from cohesive families were more likely to make such efforts. Some tightly knit gangs exerted strong pressure on their members to stop using heroin. Those users who started using heroin regularly when they were sixteen made least effort; those who started at a younger age made most effort.

Some of these self-help efforts were apparently quite successful, but most were half-hearted and not at all earnest. In time, the juvenile user becomes an adult "junkie" with a police record, his progress marked by the revolving doors of prisons and hospitals.

DELINQUENT AND NONDELINQUENT USERS

The process of habituation to heroin appears to differ among the delinquent and nondelinquent users. Most of the boys in both groups tried heroin on the first opportunity; about half had a positive reaction on first try. But, whereas the majority of the delinquents continued to use the drug more-or-less regularly after the first try, about half the nondelinquents resumed heroin use only after some time—a few weeks or more—after having experienced a more positive reaction on the second try. Yet, in spite of this greater initial hesitation at continuing heroin use, the nondelinquents ended up more heavily addicted. They took more doses daily, and they spent more money on heroin (the median weekly expenditure was $42, compared to $28 among delinquents).

The nondelinquents were also more conscious of the impact of the drug on their behavior. More spontaneously reported general dysphoria as an after-effect and concern over feelings of hostility. A somewhat greater proportion of nondelinquents had made efforts to "lay off" drugs, and fully one-fourth spontaneously mentioned that one reason for their making such efforts was the change they noticed in their own character; only one delinquent mentioned this reason. We have already noted that nondelinquents from more cohesive families made significantly greater efforts to free themselves of the habit; among delinquents, there was no relationship between family cohesion and the efforts made to "kick the habit." This might mean that they were less responsive to family influences.

STATISTICAL FOOTNOTES

a Cf. "A Study of Two-Hundred Self Committed Drug Addicts in the New York City Magistrates' Courts," a mimeographed report prepared by Max Blau-stein (no date, c. 1955). From February, 1954, to May, 1954, 253 addicts appeared voluntarily at Chief Magistrate Term Court for commitment to Riker's Island or (the women) to the House of Detention. Of the 200 who had been interviewed at intake, 42 per cent were twenty-one to twenty-nine years old; 5 per cent were younger; and the rest, older. The twenty-to-twenty-nine age group included a large proportion of adolescents who became drug-users in 1949 and 1950, when the recent wave of juvenile use started. The bulk had been involved with drugs for about four years, but twenty-five had been on drugs for more than five years. Although the data presented in the study of those 200 addicts are based only on unverified statements obtained on intake interview, we present the information about those addicts as an approximately true picture of their life.

Of the eighty-four addicts aged twenty-one to twenty-nine, all but three were males. Sixty-four were Negroes, nine Puerto Ricans, and eight white. Seventy-four were unemployed, and, of those, fifty-five had been without work for more than a month, twenty-five for more than three months. Twenty had committed themselves at least once before to the same court; sixteen had been to Lexington Hospital; one, to Riverside Hospital. Fifty-one had previous court records.

1 See Howard S. Becker, "Marijuana Use and Social Control," Social Problems (1955), 35-44.

2 This is by their own dating. The interviews from which these data were obtained were conducted in 1953. It will be recalled (cf. Chapter II) that a marked upsurge of juvenile cases was noted in 1949. Allowing about two years for these cases to come to public attention and an average of about five hundred new cases per year since then, opportunities for exposure to heroin use must have been increasing since about 1947. It is interesting to compare the dating of first chance to try among this group of users with data obtained one year later in our study of all the male eighth-grade populations in three neighborhoods differing in incidence of juvenile drug use (this study is reported in detail in Chapter IV and Appendixes G and H), including, of course, the minority who may later have become users. It may be recalled that, in the neighborhood with very high drug rates, close to 40 per cent of the eighth graders (age thirteen to fourteen) claimed to have seen someone taking heroin, 45 per cent claimed acquaintance with one or more heroin-users, and 10 per cent claimed that they had already had the opportunity to try it themselves. The credibility of these claims is discussed in Appendix H. It seems reasonable to assume that, if we could identify those who eventually became users, the percentages Would be considerably higher in this subgroup.

3 We should probably take these age trends cautiously in view of the relatively small number of cases at each age level. A more conservative analysis shows that, under sixteen, 45 per cent of the reactions were negative, as compared to 30 per cent positive, whereas at sixteen and over, only 18 per cent are negative, as compared to 52 per cent positive.

4 Forty-two per cent of the controls said "father" or "both parents," as compared to 36 per cent who said "mother." Forty-seven per cent of the nondelinquent users, 62 per cent of the delinquent users, and 69 per cent of the delinquent nonusers said "mother." In the last three groups, the percentages designating "father" or "both parents" were, respectively, 22, 15, and 10 per cent.

5 An interesting feature of this part of our inquiry was the difference in the reported image of the user supposedly held by the important adult at the boys' critical age. In the main, the image is of a mentally sick person; an unfortunate person (victim of circumstances); or a stupid person, a "sucker" who should know. better._ Most of the control group attribute to their important adult the image of a drug-user as "unfortunate"; most of the delinquent nonusers, as "stupid" (the users are similar to the controls in this respect).

6 Cf., among others, John M. von Felsinger, Louis Lasagna, and Henry K. Beecher, "Drug-induced Mood Changes hi Man," Journal of the American Medical Association, 157 (1955), 1006-1020,1113-1118.

7 Howard S. Becker claims that it is universal with regard to marijuana; Cf. "Becoming a Marijuana User," American Journal of Sociology, 59 (1953), 235— 242. However, the general effect of marijuana is much milder.

8 It should be kept in mind that these are boys who became confirmed users. It does not follow that, in the general population, all those who take a first shot or snort continue using. It may be of interest to note here that, of the fifty delinquent nonusers, thirty-three had a chance to try heroin; twenty-nine never tried; three tried on first chance and one on a later chance; but none continued. Of the fifty nondelinquent nonusers, twenty had an opportunity to try heroin, but not one of them did.

9 Harris Isbell, personal communication to Donald L. Gerard.

10 Interviews were conducted in 1953, and this weekly cost probably reflects prices of heroin in 1952. Since that time, heroin "decks" have become more diluted, and the addict consequently must spend more money to obtain the same effect from intake, that is, if the psychopharmacological effect per se matters to the user. That the psychopharmacological effect is not of great moment to many regular users is evidenced by the well-known fact that severe withdrawal reactions are nowadays comparatively rare. That is, despite the development of tolerance (the need for increased drug intake to produce discernible effects), users do not markedly increase their intake to a point that will, as an incidental consequence, produce severe withdrawal reactions. They continue taking the drug despite the absence of any discernible effect and despite the fact that, in the absence of effect, they would be just as well off ridding themselves of the habit at the cost of relatively mild withdrawal discomfort. That they continue taking the drug implies that they are getting some kind of return other than the effect of the drug. We have suggested that this return is in the form of involvement which offers them meaningful associations, a line of activity to which they can feel committed, a definite status in society, and so on. There are, of course, addicts for whom periodic abstention associated with lack of access to the drug or with voluntary withdrawal serves the function of reducing the tolerance level. If this happens often enough for long enough periods, they can continue to experience the effects of the drug in the intervening periods of use without becoming sufficiently habituated to run the risk of severe withdrawal reactions.

11 It may be of interest to note that more of them also participate in gang-organized sexual delinquencies (mainly "lineups"); this might reflect a loss of sexual interest, rather than the opposite, but the interpretation is speculative.

12 See Chapter III for a fuller report on that study.

13 Harold Finestone, "Narcotics and Criminality," Law and Contemporary Problems, 22 (1957), 71.

14 See Chapter IX for a fuller account of these changes.

15 This is not intended as criticism; it may rather be taken as a measure of the paucity of available help.

16 We should mention that, because of their servicing by the New York City Youth Board, these gangs may not be representative of other adolescent street gangs in the city. Yet some of these are highly contaminated gangs; it is our feeling that the attitude toward habituation is probably negative in most juvenile gangs.

17 Of nineteen subjects who became regular users before they were sixteen, 68 per cent made more than one effort to stop; of the forty-nine who became regular users after sixteen, 52 per cent made more than one effort to stop; of the thirty-three who became regular users at sixteen, 36 per cent made more than one effort to stop. Of the last group, 46 per cent made no effort at all, as compared to 16 and 19 per cent, respectively, of the first two groups.

18 On the basis of the method of selection, there was little point in getting data on the success of efforts to abstain by the one hundred users who were interviewed.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|