2 Now: Research and Practice at the English Addiction-Treatment Clinics

| Books - Heroin Addiction in Britain |

Drug Abuse

2 Now: Research and Practice at the English Addiction-Treatment Clinics

Lessons of profound interest are to be drawn from the British experience in combating epidemic heroin addiction, I think, but to specialists deep in the debate over the next steps in American narcotics policy those lessons are of a peculiarly frustrating kind. The experience of the British has sprung from the premise they have maintained for fifty years: that heroin (like morphine, codeine, and other opiates) has a legitimate place in medicine—primarily as a powerful analgesic, which any doctor may lawfully prescribe for his patients as his judgment dictates, but also as a tool in the management of addiction, which the British view as a medical responsibility even when an addict seems to need maintenance on regular minimum doses of heroin for months or years. When the outbreak of heroin addiction began in England in the early 1960s, fueled by a gray market in heroin prescribed to addicts legally but with lunatic generosity by a dozen or so general practitioners, it touched off considerable alarm. The British government and the medical profession reacted not by banning heroin in general medicine, but by deciding that addicts are a unique sort of patient who can no longer get heroin prescribed by general practitioners; instead, addicts must now report to treatment clinics for their heroin prescriptions. The British like to view the clinics as no more than a modification of their long-term medical approach to heroin and addiction, but since the clinics opened, the growth of addiction has slowed markedly, so that, although it is not wiped out, it seems by any standards normally applied to public-health problems to be contained. Therefore, the natural urge is to invoke the British experience with lawful heroin to settle immediate American policy issues—which may explain why that experience has regularly been misunderstood and misrepresented by both sides of the American debate. Some Americans advocate that the United States should experiment with allowing addicts to have heroin legally. Others propose, on the contrary, that the United States should expand existing programs that treat heroin addicts by long terms of compulsory hospitalization, and that this should be done through the legal process known as civil commitment—which would amount to treating addicts the way psychotics were treated before tranquilizers and related drugs revolutionized psychiatric care. These two extremes define the axis along which the dispute over American policy will move in the next several years. The dispute will grow more strident as the chief present treatments—the varieties of methadone maintenance and abstinent therapeutic communities—come closer to enrolling all the addicts who will volunteer for them, while leaving many addicts, perhaps a majority, untreated. There are already signs that this is happening: by the beginning of 1973, in several cities, including New York and Washington, the long waiting lists for methadone programs had shortened dramatically. But the lessons to be learned from the British approach to heroin cut crazily across the grain of the immediate American debate. Even the success of the British approach raises problems in applying its lessons to America, for the British have incomparably fewer addicts to deal with, and even today only a small and unorganized illicit market. The United States may yet come to heroin maintenance for addicts. The legalizing of abortion suggests how suddenly the weather can change. But if we do turn to lawful heroin for addicts, the reason cannot be that we have learned from the British success anything so simple and gratifying as that their methods would work in an American setting.

Of the lessons that Americans can legitimately draw from the British experience, the first and most salutary are lessons of doubt. Heroin swirls in myth. Addicts share myths about heroin that enslave their behavior more than the pharmacology of the chemical itself: abrupt withdrawal is an agony carrying the risk of death; once hooked, always hooked; you can't understand a junkie unless you've been one. Doctors, sociologists, policemen, social workers, science writers, and bureaucrats who deal with addicts share powerful myths about heroin, too, some of which they have learned from the addicts, and in the nature of the case it is often difficult to break down the amalgam of truth and error that makes these professional misconceptions so durable. The dialogue, insofar as there has been one, between British and Americans working in drugs has been particularly useful in exposing such misconceptions. This dialogue began to be widely audible in the United States in the mid-'60s, when the English recognized their own problem, and has grown in volume since their clinics began functioning. For one thing, the clinics provide a frame, unrivaled elsewhere, for research into heroin addiction. Their clients are not merely a good sample but nearly all the addicts there are in Britain—or so I have become convinced. The numbers are manageable. The records have been kept. The addicts are known personally.

There is nowhere in British addiction research or control the vast blank space that is at the center of the drug map of any large American city. The greatest disappointment is that only in the last couple of years have the English begun to explore the most interesting ideas for research—such as what makes the difference between addicts and nonaddicts from the same background, and which methods of treatment work best. But the lessons of clinic practice are as valuable as research. From the beginning, clinic staffs have been learning how to prescribe to addicts, what psychiatric and social services are necessary, what progress toward getting addicts off drugs is possible, and what these things cost. They have been learning these things not just with a relatively tractable, relatively well-motivated sample, such as the volunteers for methadone or for abstinent communities in the United States, but—once again—with nearly all the addicts there are in Britain. In six years, ideas have evolved, sometimes surprisingly, and diverged. Researchers, clinic staffs, and civil servants are by no means unanimous on such fundamental issues as whether an addict can be stabilized on heroin over any length of time, whether methadone is a better drug for addicts than heroin, whether many heroin addicts are able to hold employment, whether many can successfully quit drugs, whether, despite the clinics, the small black market in heroin and other drugs is a danger, or whether heroin addiction in Britain will reëmerge as an explosive social problem. The divergences of English clinic practice and opinion also have salutary lessons for Americans—lessons of doubt.

Surely the myth most deeply rooted in the rock of American experience is the one about the extreme pleasure heroin gives, the ease of becoming addicted, and the agony of withdrawal. Addicts and the general public the world around, and many doctors in the United States, believe that the truly addicted who are abruptly deprived of drugs will experience severe distress from purely physical causes. The effects of withdrawal have hardly seemed open to question. Much of the original research on withdrawal was done at the United States Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, in the 1930s. There various scales were drawn up that, with portentous scientific precision, graded the signs and symptoms of sudden abstinence from narcotics as ranging from mild, including yawning, lacrimation, rhinorrhea ( runny nose) , and diaphoresis (sweating ), through moderate, with tremor, gooseflesh, anorexia (loss of appetite), abdominal cramps, and mydriasis ( dilated pupils ), marked restlessness and insomnia, increased respiration, and higher blood pressure, all the way to severe, with vomiting, diarrhea, priapism or return of menstrual flow, and weight loss of five pounds or more in twenty-four hours. In one version or another, the Lexington scales are still quoted, often in the tell-tale original jargon, in medical textbooks. Yet as a practical matter, the relation between signs and symptoms of withdrawal and degree of addiction is peculiarly hard to determine. Though urine tests can tell the fact of narcotic use, no test exists that can tell the quantity. The English clinics bear out what anyone who deals with addicts would expect—that even in the most familiar, least coercive settings addicts will lie about the combinations and amounts of drugs they take and the distress they feel without them. Some addicts can fake withdrawal with great skill. To complicate the problem further, heroin in the United States varies so widely in adulteration that not even the addict can really know the severity of his addiction. He reckons it in dollars. The fact remains that many American doctors have seen addicts go through extreme and degrading displays of withdrawal distress.

English heroin addicts reckon their habits in ten-milligram pills, and there is no question that they have averaged far higher daily doses than American addicts can afford. In England, a few addicts, whose habits have been established for more than a decade and who are now attending clinics, are injecting six grains or more a day, 360 milligrams; a grain a day, or six pills, is cited by clinic doctors as typical of addicts getting any heroin at all. Despite such quantities, English doctors are skeptical about the demon of withdrawal. They can't doubt that it terrifies their addicts. They don't question the need, when taking someone off narcotics, to use a stepwise reduction of doses, possibly masked for the time by tranquilizers or barbiturates. But they do suspect that the symptoms of withdrawal and their severity are elaborated from a slender physical basis by a robust mixture of conditioning and self-delusion. English doctors working with addicts say they have never or only very rarely witnessed a bad case of withdrawal.

Most telling is the evidence from prisons. The ranking expert on this is Ian Pierce James, a forensic psychiatrist, who in the years of the changeover to drug clinics was medical officer at Brixton Prison, in south London. Brixton houses adult men. Because they include prisoners freshly arrested and arraigned and sent there from all over southeast England to await trial, Dr. Pierce James saw the raw realities of all kinds of drug addiction. He now teaches at the University of Bristol and treats addicts as inpatients at Bristol's Glenside Hospital. On a ringingly bright West Country morning he picked me up at the new railway station outside Bristol. Dark, of middle height, heavy-set, and infectiously confident, Pierce James can shatter a preconception about drug addiction with practically every sentence, as I discovered as soon as we had settled into his car. There are very few addicts in Bristol, he said—until the end of 1971, only two, to his knowledge. But then, in just six months, there had been at least ten amateurish thefts of narcotics from pharmacies in Bristol suburbs; a little later, one or two at a time, eleven new addicts had surfaced, all in their early twenties or their teens, all close kin or friends. "These are unusual in that none had first been turned on in London," Pierce James said. "They stole heroin, tincture of morphine, even Nepenthe—that's an injectable narcotic for children. They tried them all. But I would think that, of the eleven, perhaps two or three were in any way really addicted. You may say this mini-demie is very alarming, but in fact a fair proportion of the stolen drugs was recovered, and no illegally imported heroin has been seized from these addicts. They were certainly not buying on any black market.

"We're hard-liners about heroin in Bristol. Any addict who presents himself to hospital will be taken in straightaway for gradual withdrawal. Or he may be put on oral methadone, as in the States. But no injectable narcotics for addicts. People tend to stress the differences between heroin and the other drugs, like alcohol, but the similarities are far greater. And nobody would think of prescribing a bottle of gin fortified with vitamin B1 to an alcoholic every day. I'm taking you to Bristol Prison—that all right? I've got an office there; I'm a part-time forensic consultant."

We pulled up at a gateway through the thick prison wall. Pierce James bustled into a guardroom and came back in an instant with a ring of big jailhouse keys. "This is Dr. Judson, colleague from America," he called out to a guard, who peered briefly in. We drove into a cobbled parking lot surrounded by a steel-mesh fence. "Easier to tell them you're a professional colleague than to explain about the press." Inside the prison, the air was cool, fresh, and silent. "English criminals are a lot different from American," Pierce James said as we made our way down a steel staircase. "Much more passive, on the whole." Along a dusky corridor. "In fact, now that so many English mental hospitals have changed to open, short-stay institutions, we get a certain number of men for whom prison is really an asylum from a world they can't handle." Around a corner, through a heavy door, into a large office with a steel desk, bookcases, old maps.

Addicts don't get heroin in any British prison, Pierce James said. Instead, when they arrive they are withdrawn over a period of ten days with methadone, given by mouth. "In '68, '69, and '70, at Brixton, I was seeing about two hundred fifty people with clear signs of physical dependency on heroin every year. This was about one-quarter of the known population of male addicts over twenty-one in all England. One thing about the Home Office index—if there were a large number of addicts the Home Office had missed who thus had to be getting their supplies on the black market, you'd expect them to show up in places like Brixton. And they don't. In those years at Brixton, I saw very few addicts who were not already on the index—fewer than ten per cent.

"The junkie culture instills a phobic dread of withdrawal. These were people who had kept themselves euphoric for months on the most powerful analgesic ever in use, until they had lost their tolerance for even the normal discomforts of life—a stiff neck, a Monday-morning dysphoria. Abrupt withdrawal is usually no worse than a very bad flu. I've seen one case—one—with really extreme withdrawal signs, spontaneous ejaculation, though even that was a withdrawal not from heroin but methadone. At Brixton, I had far more trouble from barbiturate withdrawal than from heroin. Withdrawing from barbiturates, you can get convulsions, you know." Pierce James paused, then said, "We look at addiction the wrong way round, I think. We pay so much attention to the addict, and none to the kids from the same street who never become addicted. Addiction is not easy. I suspect you have to work at it. It's not an escalation; it's an escalade, rather—a series of walls to be got over. A lot of individuals start with marijuana, but heroin is a citadel few ever get to. Why?"

That afternoon, as we were driving to the train—the honorary degree had gotten me out of prison as easily as in—Pierce James came back to the difficulty of becoming addicted. "The real question is, put it this way, why do all the people who have been exposed to alcohol not inevitably become alcoholics? Why don't we compare a group of addicts with a group who have `failed' to become addicts?"

A study that reëxamined the physiological signs and symptoms of withdrawal—with results that upset received opinion —was carried out in 1970 at the inpatient drug-dependence unit at the Bethlem Royal Hospital. Bethlem is historically the direct descendant of the Bedlam, just north of the Roman Wall, that was London's first insane asylum as early as the end of the fourteenth century. Relocated three times, most recently in 1930, Bethlem is now an affiliate of the Maudsley Hospital, where the Addiction Research Unit is located; Bethlem now sprawls on the border of Kent, south of London, and has woods and lawns, walks, cricket fields and tennis courts—all told, more than an acre of grounds per patient. The drug-dependence unit at the Bethlem is on the top floor of a two-story building, with day facilities and separate bedrooms for twenty-one patients to be withdrawn, in two groups, isolated from each other not by the drug they take but how they take it—pill or needle. The twenty-one patients, who pay nothing, are attended by three doctors ( who also treat outpatient addicts at the Maudsley), two full-time psychiatric social workers, a psychologist, a full-time occupational therapist and another half-time, and twenty-two nurses. On top of all that, the unit is directed by a consultant psychiatrist, Philip Connell, a tall man, dark-haired and sleek, suited in banker's gray; he spends six half days a week there. Since the needle ward is locked, illicit drugs could be kept out; thus Dr. Connell had a controlled setting in which to study withdrawal. "I have only once seen a patient in acute withdrawal, and that was in an ambulance," he told me one morning. "There's evidence that you can control some patients' withdrawal symptoms with an injection of water—a simple saline solution. I am very skeptical about physical factors being the most important element in explaining withdrawal. Addicts have this big inventory of symptoms—I wonder whether it's not a very complicated psychophysiological conditioning. For example, there is such a thing as conditioned withdrawal, where even months after an ex-addict has been completely detoxified he can show the signs of classic opiate withdrawal, triggered just by the sight of a hypodermic syringe."

Connell set up an experiment in which a small group of narcotics addicts were given "medicine"—a paper cup of syrup to drink—once every day for twenty-eight days, which they understood was the length of their withdrawal treatment. Actually, the patients were divided at random into two groups —one group withdrawn all the way by decreasing doses of methadone in their syrup in just ten days, the other taken down in twenty-one days. Connell observed the one essential procedural safeguard for all research on the effects of pharmaceuticals: he worked "double blind," which means not only that the patients did not know what their doses were but also that all the staff members were kept ignorant of what was in the paper cups they were given to hand out, so that the staff's interpretations of patient behavior would not be influenced unconsciously by knowledge of who was getting what. (At the Public Health Service Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky, in the 1930s, the work on withdrawal was not even single blind; on the contrary, as a 1938 report boasted, the patients were encouraged to watch each other, "to observe for themselves that the abstinence syndrome is not so severe as they had imagined.") At the Bethlem, Connell and his co-workers put together for each case the nurses' daily notes, the patient's own complaints, individual interviews by doctors, and a chart that showed which of the classic withdrawal signs showed up and when, so that it became possible after the end of the twenty-eight days to relate them to the true physical state of withdrawal. "You'd expect the ten-day and twenty-one-day groups to cluster differently if physical factors were paramount," Connell said. "They didn't. The most important factor in the timing and development of their withdrawal symptoms seemed to be the nearness of the twenty-eighth day and complete withdrawal from `medicine.' "

Withdrawal, however open to question, is a syndrome addicts and research psychiatrists are at least able to talk about explicitly. But at the back of that cave shimmers the question of the pleasure heroin can give, and this leaves everybody stumbling and peculiar. The myths about the delights of narcotics are compounded of dread and fascination. In the United States, they lie deep in the popular consciousness; even American doctors who work with addicts will sometimes talk about heroin with a vehemence that strikes the observer as not only exaggerated but salacious. Primary sensations in some ways beggar words, of course. What is the redness of red? Why is sweetness pleasant? Can we hope to ask the monkey with the micro-electrode in his thalamus to type a sonnet about just why he presses the lever in his cage? Yet the pleasure of narcotics, for those who get any, must be complex—and not absolute, Iike a primary sensation. In the prevailing incoherence, one of the earliest descriptions still stands as one of the most persuasive. In 1700, a London physician, John Jones, wrote, in a book titled The Mysteries of Opium Revealed:

It causes a most agreeable, pleasant, and charming Sensation about the Region of the Stomach, which if one lies, or sits still, diffuses it self in a kind of indefinite manner, seizing one not unlike the gentle sweet Deliquium that we find upon our entrance into a most agreeable Slumber, which, upon yielding to it, generally ends in Sleep: But if the Person keeps himself in Action, Discourse, or Business, it seems ... like a most delicious and extraordinary Refreshment of the Spirits upon very good News, or any other great cause of Joy, as the sight of a dearly beloved Person, & c. thought to have been lost at Sea. . . .

It has been compar'd (not without good cause) to a permanent gentle Degree of that Pleasure, which Modesty forbids the naming of.

When the opiate is heroin, taken intravenously, some addicts claim that all those sensations are luridly intense. In the early weeks of addiction, or for some established addicts with a sharply increased dose, there is reported to be a bursting euphoria in the first seconds after injection—a rush that is described as though any sexual comparisons were inadequate. No English specialist denies the extreme seductiveness of heroin for many people. It really is an addictive drug. What they question is how the fact gets amplified—by credulity, loathing, or fear of temptation—into myth. Thus, an American doctor of great experience in the New York City addiction programs, visiting the London clinics, once said to me earnestly, "From what people tell me, it's just so goddam great, it's the most magnificent feeling in the whole world, it beats orgasm, it just beats anything." From the perspective of professionals working in the world of London drug addicts, that sounds as though mythmaking were salted with prurience.

Not everybody finds pleasure in heroin, as the English are in a position to know more clearly than most Americans. Addicts on a stabilized dose get no more than the prevention of withdrawal symptoms ( of which even the slightest will, of course, trigger a powerful conditioned urge to find relief with the drug: ask any cigarette smoker) and some tranquilizing of anxiety. Nonaddicts given heroin for analgesia in England often dislike its dissociating, deadening power. "When they gave it to me when I had a coronary, I asked them to stop it, because I didn't like its effects," a psychiatrist told me. "I preferred a certain amount of pain." If it were not for the myth of the one shot of heroin, it would be easier to see that many factors ought to contribute in varying degrees to addiction: the drug, the body and mind of the person taking the drug, his attitudes and expectations, and the immediate circumstances, for there is a great difference in the risk of addiction between a drug experienced in a hospital bed with doctor attending and the same drug taken in the back room of a derelict house with agemates. In 1968, in an experiment lasting a fortnight, two British medical investigators took heroin regularly and became physiologically addicted; one of them, Ian Oswald, kept a diary and later published some of it in The British Medical Journal—an account that ought to be set next to Dr. Jones' classic description. Dr. Oswald wrote:

We've been on heroin a week now, Stuart and I. Seven days of voluntary illness. And how ill we feel. All to settle a theoretical point. . . . My personal view at present is just one made grey and utterly grim by heroin. The extraordinary thing is that it brings no joy, no pleasure. Weariness, above all. At most, some hours of disinterest—the world passing by while you just feel untouched. Even after the injection there is no sort of a thrill, no mind-expansion nonsense, no orgastic heights, no Kubla Khan. A feeling of oppressed breathing, a slight flush, a sense of strange unease, almost fear unknown. Amid all the paraphernalia, iron-maiden contraption for fore-arm blood flow, E.C.G. and skin conductance leads, face mask and valves that go clip-clop as you breathe in, out, in, out. . . . That's taken over an hour. Unsteady and uneasy you walk to the door and down the stairs. Stand and stand, trying to micturate; eventually in a series of brief spasms succeeding. Into bed and the cold sheets set off an uncontrollable shivering and chattering of teeth, fingers blanched white. All the E.E.G. wires connected properly? The inter-corn switch on? . . . You doze, see a daft scene where someone throws something, jump with a sort of panic, and doze again. Hypnagogic hallucinations, they're called. Itching and itching, you scratch and turn. Why should people take this stuff—not for joy. Only for an hour of sudden shafts of panic and itching?

. .. Now it's sixteen hours since the last injection. Withdrawal symptoms are not bad, merely noticeable. The ever-present feeling of weariness just that much worse. A headache, yawning, shiverings and cold feelings, a nose that feels like a common cold, yawning again, hands a little shaky and poor in grip. . . . Never do this again.

.. . It's a month now since we stopped the stuff, though some measurements continue. It's been wonderful to feel fit and to relish life again. . . . I've thought more about a speaker from New York who was at a drug-dependence symposium earlier in the year—a sociologist, I think. He claimed it wasn't the withdrawal symptoms or the inner pleasures that kept men on heroin, but social pressure to belong with those who had taken this famously traditional exit. I'd thought him just ignorant of neuropharmacology and physiology. Now I suspect the greater ignorance was mine.

Certainly, not every youth who tries heroin for pleasure enjoys it enough to become an addict. The possibility that in the United States there are tens of thousands of occasional users of heroin, not addicted, has sometimes been raised, and obviously could make an important difference in attitudes toward addiction and in plans for its control. But under American conditions—with heroin, so to speak, widely available except to investigators—research into occasional users would be difficult and its meaning debatable, for many American specialists automatically consign all such users to the ranks of what they call pre-addicts. In this way, fear of the omnipotent seductiveness of heroin affects the very definition of the addict; he is grossly simplified, from the man who has acquired an overpowering desire for the drug's continuance to anybody who has tried it once. ( In form—and in ambiguity of motive as well —the error must be classed with the temperance definition of the alcoholic or the hypermasculine definition of the homosexual.) The result is circular. The way an addict is defined determines how many addicts will be found; and simplified definitions that inflate the numbers reduce the apparent chance for success of any treatment plan.

The English, now that the clinics are more than six years old, have evidence that is beginning to be suggestive about sociological questions like why some of those who try heroin don't persist—Dr. Pierce James' "failed addicts"—and they have amassed a great deal of information about the ones who do become addicted. A basic source is still the index of all known addicts that the Home Office has kept for over forty years. Since the clinics were established, the Home Office has shared responsibility for the handling of addiction with the Department of Health and Social Security ( formerly the Ministry of Health), that being the ultimate fount of staff and funds for treatment institutions of all kinds; separately from the Home Office index, the Department of Health has kept its own, more detailed records of addicts. ( Surveying the shelf where stood the black loose-leaf binders containing an up-to-date case history of every addict who has ever been to a British clinic, a Department of Health statistician said, "Nobody has a record of this kind anywhere else in the world." With unconscious heartlessness, he added, "Quite a nice size for statistical analysis.") Certain facts are established, if not always explained. In England, as in America, heroin addiction is primarily a disorder of young men. In the mid-'60s, it was clear from the Home Office index that the several thousand new addicts who made up the English heroin epidemic of those years were almost all in their late teens or early twenties. Indeed, English addicts tended to be even younger than American ones.

None of this has changed since then. The most recent study, an important five-year investigation being carried out by Herbert Blumberg, David Hawks, and a team of physicians and sociologists at the Addiction Research Unit, has begun by considering all the addicts showing up for the first time at all the London clinics in the course of twelve months, and has found that more than a quarter were in their late teens, that the average age was twenty-one years and eight months, and that only two per cent were thirty years old or more. There are some instructive contrasts to the United States: addicts in England are drawn quite evenly from the several social classes, and average about the same levels of education as the general populace, while black addicts, as they have always been, are disproportionately few. It continues to be true that English addicts are likely to use not just one drug but almost anything available, and almost at random—heroin, methadone, amphetamines and barbiturates, tranquilizers, cannabis, alcohol. This situation, too, is instructive. In the last two years in the United States, such multiple drug use, though once rare among adolescents who were experimenting with heroin, has been growing rapidly. Moving beyond these elementary descriptions, results tabulated in that investigation by the Addiction Research Unit show that a startling number-30 per cent—of the people who turn up once at a clinic (usually with enough evidence of narcotic addiction to require notification to the Home Office) never come back again. Several of the recent studies agree on a related surprise: that a long time elapses, on the average, between a youth's first injections of a narcotic and his first appearance at a clinic. The lag averages two years from the time of first regular use of intravenous narcotics, by Department of Health statistics. According to the investigation by the team at the Addiction Research Unit, at least half of those who have recently come to a clinic had injected an opiate for the first time three years earlier, and had begun injecting opiates regularly ("daily for at least seven days" was the interviewers' phrase) two years before they approached a clinic. Such recent findings hardly upset the weight of evidence that the British approach has so far been generally successful in containing addiction. Yet they are puzzling. To solve the puzzle, researchers are beginning now to examine more closely the patterns of drug use among the young. Clinic staffs, of course, see these patterns daily, and though their impressions are partial and not rigorous they offer some Ieads. Staffs say, from their dealings with the one-time visitors and with their regulars as well, that many hundreds of people may have experimented with narcotics without progressing to addiction—or at least, not yet. This impression is confirmed by a very different witness, who speaks with unusual authority among adolescents in England. Don Aitken, a thin and watchful man with hair to his shoulders, is one of the present leaders of Release, a do-it-yourself legal-aid and social-welfare unit set up by youthful activists in the mid-'60s; Release has outlived the rest of the alternative society in London, and is perceived by young England—even by many of the most rebellious youths taking drugs—to be their own organization. In a recent conversation, Aitken made several laconic criticisms of the drug-treatment clinics, but then said, "One thing we have always believed is that there are a lot of occasional users of heroin—possibly as many as there are addicts. Mostly the ones who try it two or three times and then quit. But some take it every weekend for years." Despite the evident importance, for the very definition of addiction, of the possibility that some people use heroin just occasionally, almost no formal research has been done on the subject either in England or the United States; in view of the volume of research about drug addiction that does get published, this idea must be very alien to the ruling myths about heroin. So far as I know, just one preliminary paper has appeared, an American pilot study by Douglas H. Powell, published in April 1973. Powell works for the University Health Services at Harvard; but he canvassed the drug clinics, medical services, and various community mental-health centers throughout the Boston area, and asked people who had done research in addiction, without finding a single lead to somebody who used heroin only occasionally. So he put ads in two weekly newspapers, read by the young, inviting phone calls from "chippers who want to take part in a psychological study." He got nearly a hundred calls. Most of the callers had no idea that a chipper, in addict slang, is an occasional user of heroin. About thirty-five of the calls came from people who did use heroin. Among these or their friends, Powell was able to find twelve who met his criteria: somebody who has used heroin occasionally for three years or more, but who "has never had a habit or sought treatment." He interviewed and tested his twelve intensively. He found them for the most part middle class, in their early twenties, intelligent, pleasant to talk to, highly anxious, somewhat immature and irresponsible; he included in his twelve at least two who from their thumbnail case histories are on their way to true addiction; he found that all twelve were controlling their heroin use with great care, were not involved with the addict community or way of life, and had few friends who use heroin. But, as he recognized, his group was too small to permit any firm conclusion—except the most important conclusion of all, that occasional heroin users are not rare. Some English doctors go further ( as do some Americans ) and suggest that it is actually hard for the average youth to become an addict.

The availability of the clinics and their captive clientele make possible research projects designed to penetrate the causes of addiction. Yet the questions are genuinely difficult. Addicts make unreliable witnesses, with poor and self-serving memories; the drugs they take are almost sure to have altered precisely the social behavior and personality traits that are at issue. Thus, any research, wherever carried out, that looks retrospectively into the biographies of addicts begins with grave problems. An alternative is to work forward in time; that is, to start with a group of addicts today—or, ideally, with a very much larger and younger group in which nobody is yet using drugs—and follow all its members for years in order to see what happens to them and how their fates might have been predicted. Research like that is easier in England than in America, but it is expensive anywhere, and obviously takes a great deal of time. English studies along such lines have only recently begun. Most are being done by the Addiction Research Unit, where they are designed with an intellectual elegance that is the mark of the unit's director, Griffith Edwards. Some of the most important projects will not be completed for years.

What has emerged provisionally is a social psychology of drug use, a picture of experimentation by youth in small, mutually reinforcing groups or subgroups of friends. Several things about the groups are clear enough: for one, the repeated availability of a drug or the presence of a syringe does have an effect; for another, an addict is very rarely given his first injection by a stranger—the myth of the malign pusher is another to be deflated. The decision to take drugs may hinge on almost accidental factors, but, perhaps unexpectedly, it often seems to be a deliberate choice—though a choice not just of a drug but of a role or a relationship. If a young man is using many different drugs, getting them from friends or through a number of small-scale black-market sources, he may avoid going to the clinics because they offer only methadone and heroin; or because he has heard that the clinics don't prescribe enough to satisfy him; or because he doesn't want to admit he's hooked; or because he doesn't want to be involved with authorities, regular appointments, and so on. It is also clear that within the youth subgroups, drug taking and even outright addiction are seen very differently from the way they are elsewhere in the society. Drug use may be recognized in such a group as, so to speak, an accepted way to be deviant—giving the users a recognized role to play—or the users may not feel deviant or "sick" at all, but normal and right. These small groups of addicts are obviously fluid in membership, and may differ from one to another: compare the middle-class adolescents in the West End in the late '60s, who even saw themselves as disturbed, to the working-class addicts of the East End, who seemed to clinic psychiatrists to be quite typical of their community. Yet the suggestion is that within all the various groups there must be much the same patterns of interplay by which behavior—including drug taking—is chosen and reinforced. Such group interactions, the argument runs, produced the addicts who came to be seen as typical, in three essential respects, of the epidemic: they were very young; they were not stable socially, not able to keep a good hold on their daily lives; and they infected others. In these respects they were the opposite of the addicts who had been familiar to the members of the Rolleston Committee. "Dr. Rolleston's prescription was for a very different illness," Griffith Edwards said. There were still addicts around who would have been recognizable to Rolleston: in 1967, for example, the Home Office knew of several doctors quietly taking morphine, and of 313 addicts of a variety of narcotics, including nine on heroin, whose addiction had originated in the course of treatment for something else. These types were no more trouble than they had ever been. But were there any of the new English heroin addicts who were not part of the conspicuous, infectious, degenerating youthful groups? Was the concept of the stable addict useful any longer? In 1970, Gerry Stimson and Alan Ogborne, who were then working at the Addiction Research Unit, published the results of a survey they had made of addicts getting heroin at treatment clinics in London; Dr. Stimson has since developed the results into a book. Stimson and Ogborne covered all but one of the clinics in London, and got in touch with a sample, chosen at random, of 111 addicts, which was just over one-third of all addicts in London then receiving heroin by clinic prescription. Their average interview lasted an hour and forty minutes. They turned up some interesting facts along the way: 39 per cent of the addicts said they were employed full time, and 24 per cent had indeed worked the full previous week; 84 per cent reported that in the month before the interview they had used drugs not prescribed for them at the clinic; 34 per cent said that in the previous three months they had committed some criminal act, not counting violations of drugs laws. The aim of the study was to find out how addicts differ. To get at this, Stimson analyzed the mass of interview information, and found four fundamental characteristics by which the addicts could be measured: regularity of employment, irregularity of sources of income, criminal activities, and contact or involvement with other addicts. The seventy-six men in the sample, when rated on these characteristics, clustered into four very different types. Stimson called them the stable, the junkies, the loners, and the two-worlders. The stable addicts had the highest employment scores, and the least irregularity of income, the least criminal activity, the least involvement with other addicts. The junkies were the opposite of the stable in all four variables. The loners had employment records nearly as bad as the junkies', but were not particularly criminal nor in touch with other addicts. The two-worlders were nearly as regular in employment and sources of income as the stable addicts, yet were involved with other addicts and in crime almost to the same degree as the junkies. Many other characteristics of the addicts emerged in relation to Stimson's basic four-way classification. For example, junkies were the ones most likely to have shared a syringe with a friend last week, or to have prepared an injection using the water from the bowl of a public toilet, or to have injected themselves in a public place like a telephone booth or a shop doorway. Stimson's stable addicts, on the other hand, really seemed to have their lives organized. They were being prescribed more heroin than the junkies and were the least likely to be using other drugs; they slept far more regularly, ate far more regularly, reported that they were able to work even though taking heroin, and so on. When all the addicts were followed up a year later, the stable addicts were the ones whose lives had changed least. And though the junkies were conspicuous, in point of fact they were heavily outnumbered by the stable addicts in the sample: thirteen to twenty-five.

So far, such a social psychology of drug use generally agrees with explanations that have been offered by a number of thoughtful people in the United States; there has been a lively transatlantic traffic in such ideas during the past five years. English investigators are naturally trying to push them further, though the effort soon runs ahead of research evidence yet available. Meanwhile, results that should be among the most useful are promised by several studies conceived more narrowly. Some are trying, reflexively, to uncover the attitudes and prescribing policies of clinic staffs, and what effects these have on addicts. Others aim to get the first objective evidence, where possible through double-blind studies, about which drugs and treatment approaches work best for different sorts of addicts.

In the winter of 1967-68, as the drug-dependence clinics were organized and began to open, research was far from the minds of their staffs. Their entire energies went to curbing chaos and incipient panic—their own as well as the addicts'. The addicts were wildly excited by the drugs they were taking, the life they were leading, and the public controversy they had attracted; beneath the excitement, they were apprehensive about what the clinics would do to them. The clinic staffs were almost entirely inexperienced in the work, they had almost no guidelines, and they, too, had little idea of what to expect. The law was clear but brief. Compulsory notification of new cases was to begin February 22. After April 16, to prescribe heroin or cocaine to an addict would require that the doctor have a special license from the Home Office. What the government had arranged with the senior consultant physicians, who largely run the British medical profession, was a plan that shifted responsibility for maintaining addicts from general practitioners in their surgeries to psychiatrists at the clinics. Several of the general practitioners who had been working with addicts applied to the Home Office, but not one has ever been issued a license. The rare general practitioner who wants to work with addicts now has few tools, though he can still prescribe methadone.

The treatment of addicts had always ranked low in British medicine; given the never-ending importunities of these patients, and their dubious prognosis, their unpopularity is understandable, but it was also one reason their care had been left so long and with so little support to the few doctors who had been willing to take them on. The change to drug-dependence clinics gave the work only slightly more prestige. Fourteen outpatient heroin clinics were decreed for London. Other treatment centers were later set up in provincial cities, from Belfast and Glasgow to Brighton, but these are much smaller than the ones in London, and not all take outpatients. Each clinic in London was attached to one of the teaching hospitals there. British teaching hospitals, though nominally responsible to the Department of Health, are powerful princedoms. Being independent of regional hospital boards, they could be given money directly by the department and then make their own decisions about housing and staffing the clinics, and, as it turned out, about almost every other aspect of policy and treatment as well. Though American visitors often find it hard to believe, there is no central direction or administration of the clinics.

Several clinic psychiatrists also pointed out to me that British psychiatry is different from American in ways that affect one's understanding of the clinics. It is less highly regarded, and does not have the strong intellectual tradition that supports it in the United States. Its practices, out of which the drug clinics evolved, are those of a cadet branch of physical medicine. Among the consultant psychiatrists in 1968, perhaps a majority were extremely uncomfortable about the idea of maintaining addicts with heroin, and many protested that their profession was being forced into unethical conduct just to solve a Home Office problem, the police problem, of preventing the growth of an illicit market. Yet there were ironies. To possess one of the new Home Office licenses to prescribe to addicts became, instantly, a mark of status among psychiatrists; some six hundred licenses were issued, many to the same men who had said categorically that they couldn't conceive of giving an addict heroin. The licenses are only now being weeded out. Most were never exercised. To recruit the staff for the new clinics, although fewer than two score doctors were needed, was not easy. With the general practitioners excluded, nobody who had any experience whatever was left, except the few consultant psychiatrists—Thomas Bewley, Philip Connell, James Willis, and a very few others—who had been working with addicts as inpatients in hospitals. These at first spread themselves over several clinics each. Virtually all the full-time members of the clinic staffs, though, were new to addiction. Some of them say even today that they were press-ganged. The low standing of the drug-treatment centers was evident, too, from the quarters they were given, which were quickly converted from other uses, and were usually cramped, tacky, and even hard to find. "We were started in the old chest clinic," I was told by Martin Mitcheson, the psychiatrist who runs the drug clinic at University College Hospital, in London. "You must understand that addiction has succeeded tuberculosis as a social disease, and you hide addicts at the backs of hospitals." Yet the shabby clinics certainly didn't seem crisp and institutional; they almost felt like part of the underground scene, and, if anything, made the addicts feel safer. "Anyway, unlike your American street junkies, our addicts have always been doctor-oriented," an English social worker told me in 1968. That winter, the addicts began to sidle and swagger into the clinics—at first mainly the wiser, middle-class, Piccadilly addicts but by spring also the half-articulate youths with their Cockney triphthongs. These were the high months in England for acting out the style of the junkie life, even if you were only sixteen and were injecting heroin only once a week. The addicts were strung out on apprehension and excitement. They were used to wheedling and bullying their general practitioners. They thought they had a legal right to heroin. They sensed their numbers and cohesiveness. The raw clinic staffs immediately faced the problems that had overwhelmed even the most responsible of their predecessors among the general practitioners who had prescribed to addicts.

The medical skills required for dealing with a heroin addict are fairly crude, the administrative precautions minimal—or they are if maintenance is the first aim and no sizable black market is competing. The new clinics did have a prototype. The city of Birmingham had already experienced its own small epidemic of heroin addiction, and this had been fought to a standstill a year or so earlier by John Owens, at All Saints' Hospital there, and his head nursing officer, Edward David Hill. Dr. Owens, a psychiatrist, had come to All Saints' in 1964 and set up a clinic chiefly to treat alcoholics, though he had expected to get an occasional more exotic case from Birmingham's large population of Pakistani and Indian immigrants. To this day, his clinic sees a number of Sikhs, older men, who have become addicted to an opium tea they brewed by steeping dried poppy heads in boiling water. They are given morphine tablets, by mouth, some as much as two grains a day. Without morphine, the Sikhs can't function. With it, they work and support families. Owens successfully withdrew his first young heroin addict, as an inpatient, in the summer of 1965. By the end of the year, he was getting two or three new cases a week. By March 1966, there were about fifty addicts in Birmingham. Owens determined to monopolize heroin there. Working with the police, the pharmacists, and the local medical association, he got everyone to agree that nobody else would prescribe to addicts.

The practices that Owens' clinic then evolved were simple.

When a new addict presented himself, Mr. Hill, the nursing officer, would take a urine sample, complete a brief questionnaire, and then examine the addict's arms. "It's not too hard to read the scars," Hill told me. "Tattooing of veins, signs of abscesses, a needle or a pin—some lads would come in, swear they were heroin addicts, and show an arm full of punctures, every one made that same day with a pin." An hour later, Owens would interview the new case. Then the addict would wait, under observation, for the results of the urinalysis. Analyses for drugs have been developed to the point where they are not difficult, just tedious and finicky. Narcotics, barbiturates, and amphetamines can all be identified, but only by running three different series of separations, while extra tests for tranquilizers and even for aspirin may be necessary. ("Poly-drugs? They'd inject salad cream!" Hill told me in Birmingham. A doctor in New York told me of an addict who once injected peanut butter.) Heroin itself breaks down to morphine in the body before it is excreted. Making a clear distinction between, say, morphine and codeine may take an additional technique. Some American laboratories are now equipped so that a single technician can test sixty urine samples that thoroughly in a working day, but when the Birmingham clinic opened, the methods available were much slower. If the tests indicated that a new addict at All Saints' had taken heroin that day, and if he was showing withdrawal signs, Hill would give him perhaps half a grain of the drug and a syringe; the way he injected the drug would indicate how experienced he was, Hill said, and the effect of the dose could be judged. Owens began by prescribing heroin to addicts weekly, but found they would use a week's supply in two days. Given three prescriptions a week, they would shoot a long weekend in a day. The clinic was soon writing prescriptions for each day. It was open several afternoons and one evening a week, and addicts were required to come in every week at an appointed time for a talk, however brief, with Owens, and a urine check. To stop prescription forgeries and to keep all the addicts from congregating at one place, Owens began introducing each addict personally to one of several selected pharmacists to whom the addict's prescriptions were thereafter mailed in weekly batches. These procedures that Owens and Hill devised have become standard clinic practice.

"So many people think the be-all and end-all of the clinic is to get them off heroin," Hill said. "We think of what we do in relation not just to the addict but the community. If we could maintain forty on heroin, and then never get another addict, we would do it. But of those original fifty that had come in by the spring of '66, to the best of our knowledge only five are still on drugs. And only two deaths. There's no reason to get the deaths. With no reason for overdoses, and with clean—even domestically clean—syringes, you don't get septicemia, and you don't get liver damage. They are more susceptible to sickness in general, it's true."

The clinic at All Saints' drew attention and many visitors. The Home Secretary then—it was the midpoint of Harold Wilson's earlier Labour government—was Roy Jenkins, who was personally committed to an energetic program of reforms, including, for example, a liberalization of the laws covering abortion and homosexuality. Jenkins visited the Birmingham clinic in the fall of 1967. "As I recall, I was very encouraged by this visit," he told me in a conversation at the House of Commons early in 1973. "I was encouraged by their evident and apparently well-grounded confidence that a clinic approach to controlled prescribing could work." That fall, Jenkins also visited the United States, to learn about the drug problem, particularly in New York City. "The American experience certainly never began to move me to consider total prohibition of heroin here," he said. "I saw a lot of people and a lot of treatment centers. The thing that struck me first and most forcibly in the United States, however, was the link-only too obvious a link—between addiction and crime. Such a link did not exist in this country, and to go out of the way to create such a link seemed self-evidently foolish. Throughout, I was firmly against criminalizing addiction, as I think we all were. What was wanted was other kinds of social controls, for the addicts under medical care and also—very importantly—for the doctors themselves. We thought that a chief objective had to be to institutionalize the care of addicts through the clinic setting, in which nobody would be acting alone but, instead, as part of a group with checks and supports for the doctors as well as the more visible controls supporting the addicts."

The difficult first months of the new clinics were described to me with remembered disquiet, even five years later, by Margaret Tripp, the psychiatrist who ran the Addiction Unit at St. Clement's Hospital, in London, for its first three and a half years. In the early months of 1968, all the new English clinics prescribed heroin with fair abundance. They had little choice, their staffs believed, if they were to prevent the growth of illicit sources of heroin and keep addicts from turning to other drugs. "As you clearly realize, our purpose at the beginning was to seduce the buggers," Dr. Tripp said. "But a lot of my colleagues would cheat themselves about this. When the general practitioners were prescribing heroin—ah, that was vicious. `But when I give heroin, it's medical treatment.' " We talked in the kitchen of her house in Colchester, an hour east and north of London, while she fried sausages for her children's lunch and then put out cheese and fruit for us; as she worked and talked, her recollections at first seemed self-depreciatingly slangy and almost cryptic, but gradually she built up a remarkable impression of the psychological pressures and even physical dangers that clinic staffs faced in bringing a large number of addicts under control—and an impression, as well, of the stubborn and womanly integrity that kept her at it. She had trained in psychiatry "at the bin down the road," meaning the mental hospital in Colchester; in the fall of 1967 she had answered a help-wanted ad for drug clinic staffs in The British Medical Journal. "There was no competition for the job, needless to say! I went to St. Clement's in January. Started dishing out heroin at the end of February." The addicts in her area—St. Clement's is just off the Mile End Road, which is the Piccadilly of the Cockney East End—were drawn from a distinctively urban, working-class community with a marked criminal tradition, centuries old. She inherited most of the addicts who had been getting heroin and cocaine, and other drugs as well, from the notorious Dr. Christopher Michael Swan (he who later went mad and is now in Broadmoor). The addicts' extortionate pressures on Swan had grown so great that he turned over a block of signed prescription blanks to one young man, who sat in the doctor's surgery filling them in and collecting the fee. For about seven weeks, from the opening of St. Clement's clinic until the Home Office licensing regulation at last came into force, on April 16, Dr. Swan was still legally prescribing heroin in generous quantity, in competition with Dr. Tripp.

"Addicts have this very bent relationship with their doctor," she told me. "I had the same pressures on me in the outpatient clinic that Swan had in his surgery, and I therefore had a lot of feeling for him. He was an unfortunate and ill-used man, and when I first met him was by no means mad. He explained to me at great length and in great detail why the clinics were going to fail. At that stage, he began to see himself as the only one who understood the addicts, and as their savior. I was fortunate in being a woman. They were often wildly aggressive and threatening, but they would not actually harm a woman, though there were times I was not sure of that. Later, some of my favorite patients were the ones who had leaned on Swan, because they were the ones who were most solidly, genuinely East End. At the beginning, the addicts were ostracized by everyone else at the hospital; even the staff was ostracized. We weren't bothered at first about overprescribing, but wanted to be generous enough to net all the addicts at one go. Quite unawares, we were doing just what the government really wanted. We had over a hundred patients by May. They ranged in age from seventeen to thirty-five. Some of my older guys were taking up to fifteen grains of heroin a day. The highest I ever had was a musician, older, working regularly for the B.B.C. He took twenty grains a day. But most of my guys were around seventeen years old, and for them a high dose would be four or five grains." I asked her if it was possible to stabilize an addict—his dose, and his life—on heroin, and she said, "This is one of those things you don't believe in the States, isn't it? But a lot has to do with the intentions of the guy himself. Some seem insatiable; some do stabilize. I had kids in the same dull job for months—sometimes we even found ourselves wondering why they weren't more ambitious. When we got all the addicts in, we began to get the doses more nearly right; knowing the boys and their families—they were ninety per cent boys, and most were living with their families—we made fewer mistakes. After a year, perhaps half of them had stabilized their dosage." When Dr. Tripp's children had finished their lunch and gone out, she said that prescribing heroin to addicts had not been comfortable. "You know, I'll be paying for this conversation for days. It was a profound emotional experience. At first, I felt like the worst example of the Melanie Klein bad mother. I was giving these cases—and they were my patients, and they felt like my children—I was giving them this poison. I got over that, later. For the most part.

"You Americans are at the stage of calling addicts delinquent. When we started, we were calling them sick. I can see how that would look to you like a big advance. But after a time, when I knew them, I wasn't calling them anything. I gave up being a headshrinker with these guys almost immediately. It would be nice if you could profit by our mistakes. It would be nice if you could miss out the `sick' stage altogether. The addicts themselves are against being labeled sick. The clinics force the addicts to be patients. The main reason I finally left, a year ago, was that to perpetuate my job I'd have had to create work, to go on labeling people sick who had not yet perceived themselves that way."

Margaret Tripp made me see that though the clinics were not explicitly planned in these terms, probably the most important thing they achieved was to restructure the relation between doctors and addicts. On the one side, the clinics erected an entirely new protective scaffolding around the doctors, and, on the other, they broke down many of the supple but tenacious bonds that had joined the addicts, and had lent addiction much of its strength. "This is what that entire recent lot of drugs legislation is about—not drugs at all, but getting at my profession," she said. "What do the clinics do? They save a physician from isolation: no man in isolation can hope to deal with a hundred drug addicts."

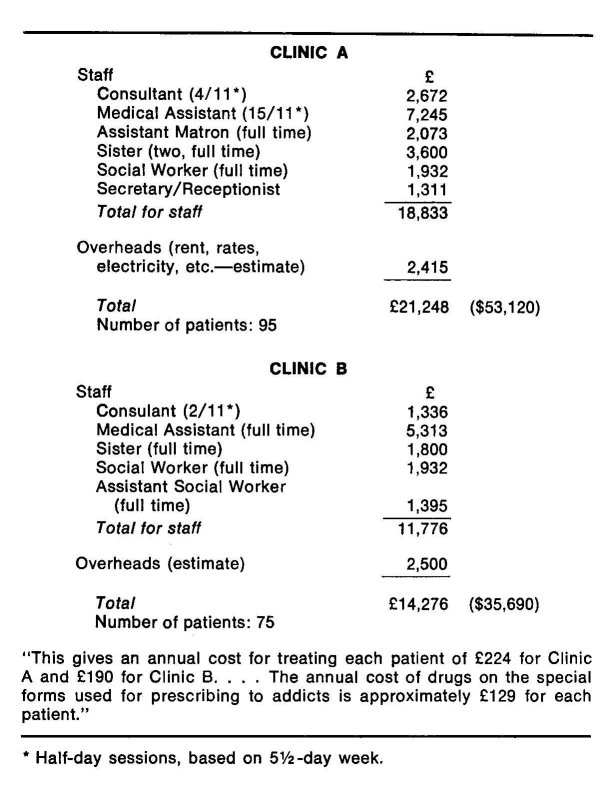

A hundred addicts is about the number actively attending a typical London drug clinic. Each is required to come in once a week; the hundred appointments are scheduled across two or three long afternoons, with one night session for those who can't get away from their jobs during the day. To deal with a hundred addicts, a clinic has the half-time services of a senior psychiatric consultant and the full time of at least one other psychiatrist. There are also two or three nurses. Four social workers for every hundred addicts are called for by official standards; clinics usually have two, though some have one more, half time. Organization on a comparable scale to treat New York City's 150,000 true heroin addicts, or its quarter-million users ( if that really is how many there are ) , would require over fifteen hundred clinics and, at a doctor and a half each, nearly twenty-three hundred fully qualified psychiatrists; at the beginning of 1974, the American Psychiatric Association had 2,007 members in New York City, and the city had 19,641 doctors of all sorts. Some four thousand nurses would be needed, and from four to eight thousand social workers. In London, each clinic is at a different hospital. Within the clinic, and enveloping the clinic staff within the hospital as a whole, there is a network of almost constant professional contacts that range upward from canteen tea breaks; the support these contacts give was pointed out by both Roy Jenkins and Dr. Tripp, and had been explained to me by Martin Mitcheson, of University College Hospital. "At the teaching hospitals, we are much more subject to our colleagues' criticisms and unspoken controls than we would be if we were operating an independent clinic or working anyplace that doesn't have a structure of committee meetings and dining clubs and so on," Mitcheson told me. "I think this is important. And then, you see, London is a small enough drug scene so that we all meet together, quite spontaneously this grew up. Each of the various subprofessions concerned with the clinics has a monthly meeting. The nurses meet—over wine and cheese, I believe. The social workers meet. The doctors meet. The secretaries don't—but you know, perhaps they should, for they have a key role when the addict walks in the door. And then there's the official quarterly meeting at the Department of Health, which we all have to go to, because we're terrified somebody else might get an extra ration of jam. Which is another control mechanism. Now, I don't think this could be done in the States, given the size of the American drug scene."

For addicts, the advent of the clinics meant a change in social relationships, too, but in the reverse direction: the cohesive youthful subgroups characteristic of addiction are now quietly discouraged and replaced in a variety of ways. "When you get a group of addicts together and talking, they reinforce each other's addiction" is an English clinic maxim. Whatever the psychiatric orientation of the clinic directors, almost all of them actively resist the therapeutic and encounter groups they see as the most conspicuous, and bizarre, feature of American rehabilitation efforts. "Oh, yes, we've watched your shouting sessions on television," Margaret Tripp said. An English clinic's waiting room will not often have as many as half a dozen people in it, counting girl friends and babies. Mailing of prescriptions directly to pharmacies, each chosen because it is near the addict's job or home, with a pickup hour set, and with no pharmacy asked to handle more than a few such prescriptions, has shut down Piccadilly and the Mile End Road as marts for addicts. Perhaps the most conspicuous change is the transformation of Boots' all-night pharmacy in Piccadilly Circus, where addicts used to wait by the dozen, edgy and shrill, as midnight approached and their next day's scripts would be negotiable. These midnights, Boots' is deserted; only about twenty addicts fill their prescriptions there now during the entire day. The temptation to flaunt junkie behavior has been greatly reduced; no small part of the British toleration of legal addiction is due to the clinics' success in getting addicts out of sight. Addicts can no longer swarm from one doctor to a new one; clinic transfers must be justified, and are now infrequent. American doctors working with drugs often seem to think that the size of a prescription written at an English clinic is set by outright bargaining between doctor and addict; Americans I have talked with don't mention poison but flinch at prescribing pleasure, and to haggle over it seems intolerably unprofessional. Haggling undoubtedly used to take place between addicts and prescribing general practitioners; it is no longer at all characteristic of English addicts' meetings with their doctors. Though practices vary somewhat, at the best-run clinics the prescriptions for the next seven days are determined and written during a weekly closed-door all-staff conference. Inescapably the prescription is what brings the addict in every week; once he is there, what he talks about with the psychiatrist and the social worker, if he is at all stable, will be his job, his housing, his parents, his girl, ordinary things—and drugs chiefly in relation to these. The concerns of the occasional female addict are often still more poignant, since she is very likely to be living with a man who is an addict, too, and may also be painfully anxious about the effects of drugs on possible children. "Many of my addicts like to pose as deliberate dropouts from the middle class," Mitcheson said at University College Hospital, "but I know them well enough by now to be sure they don't want to write a William Burroughs book. What they do want is a semidetached council house and a car." ("Most of ours," said John Mack, a psychiatrist at Hackney Hospital, "have already got a council house and a second-hand car.") Thus, the structural transformations brought about by the clinics have enabled the growth of the therapeutic essential—a relationship between doctor and addict in which both must expect that they will be working together over months and years. If the clinics have accomplished nothing more than this, they must be counted a heart-stirring success.

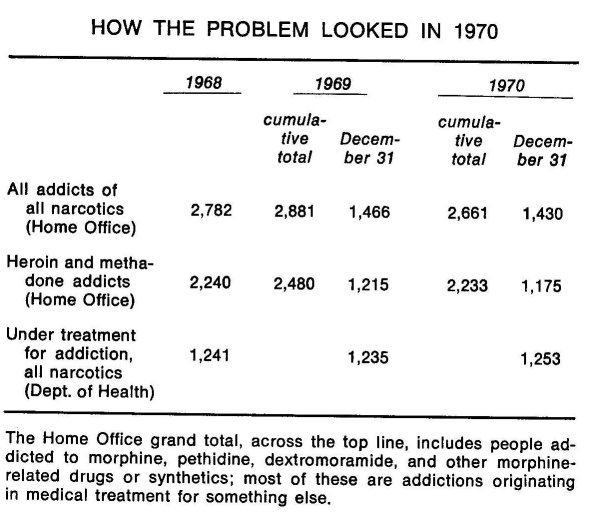

That was not the first and most visible accomplishment, however. The numbers were—the marked slowing of the growth of heroin addiction. It is surely one of Satan's greater strengths that in social crises the numbers make headlines, while in social victories the numbers make only statistics. But since any judgment of the clinics depends on how the statistics are viewed, they can't be left to the many who view them with prejudice. The Home Office index continued to yield several numbers, in parallel, working down from the all-inclusive total of addicts of all kinds of narcotics. In 1967, that top figure had been 1,729. Three-quarters of those, 1,299, were heroin addicts. Nine people were still counted as having acquired their addiction to heroin in the course of medical treatment for something else, usually cancer; these, if not in a hospital, were transferred to the new clinics, too, but, as a Home Office source said, "We didn't insist that a seventy-year-old come sit in the waiting room every week with the junkies." That left 1,290 heroin addicts in 1967—an apparently irreducible figure. As the clinics were being set up, the Home Office bravely maintained that the true number of narcotics addicts of all kinds could not be more than three thousand.

Through 1968, as compulsory notification and the clinics brought the addicts in, the index swelled. By the end of 1968, the year's total for all addicts known to the Home Office reached 2,782. A year later it was 99 higher, and near these levels it seems to have stabilized. Even allowing for some the index will have missed, the Home Office estimate for narcotics addicts of all kinds turned out to be essentially right—and, it is said, nobody was more surprised than the Home Office. Of the fewer than three thousand addicts, the ones that counted were the ones taking heroin-2,240 of them. Death, emigration, prison, and cure had subtracted some addicts since 1967, so the 2,240 included 1,306 new heroin cases. Thus, it looked at first glance as though the rate of increase had itself increased, which is how the English changeover was often reported in the United States. So another sturdy myth was born, for the truth seems to be that though there were indeed new addicts, the apparent size of the increase was due to the change in the way the numbers were collected—that is, the introduction of compulsory notification—combined with the very real pressure, where-ever several addict friends had been dividing up a single private prescription, for them all to come to a clinic. At the end of the 1960s, no one could seriously charge that the index, newly based, was missing any vast number of heroin addicts. If it had been, these would have begun to turn up with withdrawal signs in police stations and jails, in hospital emergency and casualty wards, and in morgues. But Ian Pierce James' experience in those years at Brixton Prison, where fewer than ten per cent of the many addicts he saw were not on the index, was duplicated everywhere else. For instance, of the ninety-eight addicts who died in 1969 and 1970 only four were not known to the Drugs Branch.

Besides heroin, the clinics had methadone to work with, and when the doctor thought an addict needed a barbiturate or tranquilizer, he could prescribe it—in pills, of course. But other strong, injectable drugs were often available to addicts outside the clinics, and from time to time, unpredictably, a craze for one of these would sweep the English adolescents. The first of these to confront the clinics, in 1968, was injectable methyl-amphetamine. As the day approached when they could no longer give addicts heroin, two of the prescribing doctors—Petro and then Swan—had begun deliberately switching their customers to methylamphetamine, and this drug helped create the manic emotionalism among young addicts in the clinics' first year. It was marketed in thirty-milligram ampoules, almost entirely by one supplier, Burroughs Wellcome, under the trade name Methedrine. Injected repeatedly—and Pierce James warned his colleagues in a letter to The Lancet in April 1968 that some users were injecting ten ampoules a day—methyl-amphetamine produces a psychosis that had been described a decade earlier, at the Bethlem Royal Hospital, as "indistinguishable from acute or chronic paranoid schizophrenia." Though the London youth newspaper International Times shouted the slogan "Speed Kills," borrowed from the United States, Pierce James saw over four hundred cases of intravenous amphetamine use in Brixton Prison in 1968. That October, with inspired simplicity, the Drugs Branch and the Department of Health got Burroughs Wellcome to agree to supply Methedrine ampoules only to hospitals. The Methedrine craze was quenched literally in days; the temperature of the addict community plummeted. Observers are still surprised that the strategy worked, and baffled that no laboratories in England ever made amphetamines illegally, as laboratories in the United States and Canada do.

"The drug problem is like a huge soft balloon," an observer at the Home Office told me. "You squeeze it down hard here, and it pops up there. Usually where you weren't looking. Any tightening up or restriction you do has got to be seen in relation to the whole field of choice open to the people you're dealing with." Those who had been injecting themselves with methylamphetamine were thought likely to substitute injections made from amphetamine tablets, which was, for example, what adolescent drug takers in Sweden were doing at the time. Little of that occurred. Instead, many who had learned with methylamphetamine to be dependent on the hypodermic needle switched to heroin or to injectable methadone. By the spring of 1969, others were injecting barbiturates, which they did by crushing and then dissolving them in water and filtering the liquid through cotton wool. Intravenous barbiturates, except for a couple of briefly acting anaesthetics like Pentothal, have almost no place in medical practice; their use by adolescents is an English phenomenon almost exclusively, so far.

English doctors say that intravenous barbiturates ( like methyl-amphetamine ) are worse than heroin. Addicts injecting barbiturates don't simply get euphoric and then sleepy; they become profoundly confused and unable to take care of themselves. The drug, in the way it is prepared and injected, will produce thrombophlebitis, clotted inflammations of the vein—or, if the vein is missed, abscesses that can become infected. Patients withdrawing from barbiturates are likely to go into convulsions. Through most of 1969, the sick, filthy, shambling youths on barbiturates were as noticeable in Piccadilly Circus every night as the heroin addicts once had been. "But barbiturate injecting is self-limiting," a doctor told me grimly. "With these patients the immediate problem of treatment is to keep them alive." At that same period, youthful drug takers not compulsively attracted by the needle reverted to swallowing amphetamines, or, in a new fashion, sleeping pills. On 11 January 1969, a letter in The British Medical Journal warned of the growing popularity of a capsule with the trade name Mandrax, in which the chief ingredient is methaqualone, one of a class of nonbarbiturate hypnotics that has recently been discovered; in the United States, methaqualone appears under the trade name Quaalude. Users say methaqualone produces not only intoxication but sometimes hallucinations and amnesia; it is still popular today in England, and by the fall of 1972 its use among adolescents had begun to grow rapidly in the United States. Another pill was Valium, from still another new class of hypnotic and depressant drugs; a large dose of Valium is hard to distinguish in its effects from alcohol. Almost any pill available was being tried, and often in combinations in which two drugs would act together to produce unpredictable and greatly intensified effects. And almost anything was available: though the size of the illicit market should not be exaggerated, it has of course been fed, sporadically and uncontrollably, from the lawful market, the capsules and tablets prescribed in unimaginable hundreds of millions a year by perfectly ordinary general practitioners to perfectly ordinary patients. English surveys of what doctors prescribe have shown repeatedly that these mood-changing drugs go typically to patients who are middle-aged, seventy to eighty per cent women, and in small regular amounts that suggest inescapably that a drug dependence is being maintained The size of this lawful market would be very hard to exaggerate: in England and Wales in 1970, there were about 2,000 deaths from barbiturate poisoning, and at least 1,300 of the deaths were suicides; at the end of that year the Home Office knew of 1,175 addicts of heroin or methadone or both.

In the fall of 1968, just when the methylamphetamine problem was solved and multiple-drug use was growing, the first traces of illicitly imported heroin began to appear. Its arrival was due to no organized criminal effort and, indeed, was fortuitous; it was not intended for English addicts, and at the start few of them would touch it. Unlike the pure, safe tablets they were used to, illicit heroin in England is a brownish powder, which in recent seizures has been from ten to twenty per cent narcotic ( and very low-grade narcotic at that, the morphine not fully acetylated) adulterated with caffeine and sometimes with barbiturates as well as with fillers ranging from sugar to talc. The real surprise was its source. Though France is so close to England, and has been said until recently to be the proximate source of most heroin in America, not since His Majesty's Customs seized six grams of French heroin in 1937 has there been the faintest suspicion that any important quantity was coming across the Channel. The illicit brown granules come from Hong Kong. Heroin addiction is widespread among the Chinese in Hong Kong, I was told early in 1973 by Commander Robert Huntley, of Scotland Yard, who had just been there. The rate is at least one in seventy, perhaps one in thirty. The users there rarely inject the mixture, however; instead they sprinkle it on metal foil, light a match, move the flame beneath the metal, and inhale the fumes through a drinking straw in the nostril or, when pressed, through the cover of the matchbox. They call this "chasing the dragon." Illicit heroin in England is known as "Chinese" to addicts, police, and doctors alike. One afternoon late in 1968, I was talking with a leader of the London youth underground, a beautiful ex-model named Caroline Coon—it was she who organized Release, as a twenty-four-hour-a-day legal-aid service for adolescents arrested on marijuana charges—when two of her addict friends stopped in with the news that something called Chinese heroin was on sale in the East End. The caffeine in it, they said, gave it an exotic potency. That was its first appearance among the addicts.