1 The Past: Heroin Maintenance and the Epidemic of Addiction in England, to 1968

| Books - Heroin Addiction in Britain |

Drug Abuse

1 The Past: Heroin Maintenance and the Epidemic of Addiction in England, to 1968

My first encounter and only personal experience with heroin took place in 1966, when I was living in London. What everybody knows about the British and heroin is that they supply it on prescription to heroin addicts. But my first sight of the drug seemed to have nothing to do with addicts. My elder daughter, then seven, had caught a cold and developed a hacking cough. The doctor listened at her bedside—English doctors still sometimes call at bedsides—and then wrote out a prescription for cough medicine. As we left together, I on my way to the pharmacist's, I glanced at what he had written, and disentangled the words "elixir diamorphinae."

"Isn't that heroin?"

My tone made the doctor laugh. "You've got the American horror of it," he said. (I certainly had.) "Really, the amount is homeopathic—well, almost. And it's the best thing in the world for a bad cough, heroin."

The pharmacist at the corner filled the prescription while I waited, and without so much as giving me a hard look. The medicine seemed to do the trick: my daughter stopped coughing. Later that winter, I had an irritating night-time cough myself. There was still some syrup at the bottom of the bottle. I swallowed a spoonful. Homeopathic dose or not, it killed the tickle.

Cough medicine was, in fact, heroin's first general therapeutic use. The stuff was discovered in 1874—seventy years after the original isolation of morphine from opium—when the London chemist C. R. Alder Wright, starting an exhaustive catalogue of the actions of organically derived acids on morphine, cooked some morphine with acetic anhydride, a pungent liquid closely related to the familiar acetic acid that gives vinegar its zest. Heroin was christened in 1898 by Heinrich Dreser, chief pharmacologist at the Elberfeld Farbenfabrik of Friedrich Bayer & Company, in a paper he read to the seventieth Congress of German Naturalists and Physicians, in Düsseldorf. (A year later, Dreser coined for Bayer another memorable name—"aspirin.") He announced to the congress in Düsseldorf that tests of heroin on animals in his laboratory —and, at his direction, on sixty unsuspecting patients in the dyeworks' own hospital—demonstrated that the new narcotic was sovereign for cough, catarrh, bronchitis, emphysema, tuberculosis, and asthma. It was free of the undesirable side effects of morphine, such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, and loss of appetite. Then, too, he reported, patients said great things about the drug: "Herr Doktor, die Pulver, die Sie mir gaben—that powder you gave me, doctor, it worked so well, right away when I took it I felt relief"—the whining supplication echoes back, surely, to the first apothecary with a new drug to pluck the sleeve of Hippocrates himself, the promise that patients will be eased and full of thanks. Doctors, after all, are gratified very deeply, close to the root of their being as doctors, by certain kinds of response that drugs can elicit from patients. Beyond others, the opiates—especially heroin—are capable of tangling up a doctor's motives. This unpleasant fact intrudes again and again in the control of drug addiction.

In Dreser's list of heroin's heroic properties, he mentioned in passing that it seemed not to be habit-forming. That error, of course, has made the introduction of heroin one of the great cautionary tales of medicine, not to be equaled until another German drugmaker launched another analgesic into the vocabulary—thalidomide. Dreser published his report in Germany in the fall of 1898; in November, his talk was noted by The Journal of the American Medical Association; within weeks, other clinicians were confirming heroin's efficacy in the treatment of cough. In December, The Lancet, the British journal of clinical medicine, called for English tests and noted that heroin was already being distributed by the London agency for Bayer, 19 St. Dunstan's-Hill, E.C.

Heroin is lawful today, for at least some medical uses, in nine of the 188 countries and territories whose requirements for opiates and cocaine are compiled and published every year by the International Narcotics Control Board, an organ of the United Nations, in Geneva. (Only the People's Republic of China is unreported.) Most of the heroin legally manufactured in the world is made the same way Wright first made it in London in 1874. Given the crude morphine, to synthesize heroin takes far less apparatus, time, and chemical experience than, say, to distill a drinkable whiskey. The morphine molecule is a compact linkage of three carbon rings, crocheted together by a fourth loop containing a nitrogen atom. Even some vitamins are chemically more complex. Heroin is exactly like morphine except that from each of two of the carbon rings there dangles a short chain of atoms taken on from the acetic anhydride. Pure heroin is a white powder almost insoluble in water. Exposed to air, it begins losing acetyl groups, smelling vinegary, and turning pink. Heroin does not appear in The United States Pharmacopeia. The more stable salt of the stuff is listed in The United States Dispensatory, a handbook for pharmacists, as "diacetylmorphine hydrochloride," and in the British Pharmacopoeia as "diamorphine hydrochloride." This is an odorless, almost white crystalline substance with a bitter taste. It dissolves readily in water. In most of the countries where heroin is still legal, the amounts permitted are small: 250 grams in the Netherlands in 1974, for example, 100 grams in West Germany, and the same in Ireland, down to 10 grams in Poland, 9 grams in Bahrain, 7 grams in New Zealand. Great Britain licensed the production of 80 kilograms in 1974 (10 kilos less than the previous year), out of the total world requirement of 95 kilos 606 grams. That entire lawful British supply of diamorphine is manufactured by a Scottish firm, Macfarlan Smith, Ltd. ( cable address "Morphine"), of Edinburgh. Starting with imported opium, and under extreme security precautions—even the firm's wall calendar, with a dreamy painting of Pa paver somniferum, the opium poppy, is restricted in distribution—this factory produces a variety of alkaloids. The 80 kilos of heroin would have a street value in the United States of over fifty million dollars. It is unlikely that Macfarlan Smith makes enough profit on its heroin to be worth the trouble. None of it is exported. Thirty-five kilos will be converted into a different drug, nalorphine, which is a narcotic antagonist. (Injected, it counteracts any morphine or heroin in an addict's body, throwing him quickly into withdrawal.) The 45 kilos remaining for consumption as diamorphine hydrochloride may not all be used. In fact, the legal consumption of heroin in Britain in 1972 was down nearly a third from its peak in 1968. Lawful heroin in Britain is most commonly seen in white tablets about the size of saccharin tablets, each containing ten milligrams, one-sixth of a grain.

The pills cost the National Health Service two and a quarter cents each. To get a prescription filled ( whatever the drug or dose ) costs a patient the equivalent of fifty cents.

How heroin or any other opiate works on the central nervous system is not fully understood. Neurobiologists propose that each molecule of narcotic fits exactly, key in lock, into a receptor on the outer membrane of a nerve cell, and thus changes the nerve's response to the normal stimulating chemicals produced and transmitted by other nerve cells nearby. If the nerve, to compensate, grows more receptors, or if it varies its utilization of the normal chemicals received from its neighbors, that would explain why narcotic doses must be increased to achieve the same pain relief or the same pleasure. Pharmacologists at Johns Hopkins University demonstrated recently that molecules of morphine or methadone do attach themselves to specific types of cells within the brain. More recently still, Avram Goldstein and colleagues at Stanford have announced that they have extracted and partially purified, from brain cells of mice, receptor molecules that interact specifically with opiates. The day is surely not far off when the structure of the receptors will be known and the mechanism of their response to opiates will be worked out atom by atom; yet until then such models remain no more than highly educated metaphors. But the fact of heroin's profound effect on the nerves is of course unquestionable. English doctors, speaking from clinical experience with heroin, call it the most potent analgesic they know, and a powerful tranquilizer The effects are subjective and hard to measure; heroin and morphine differ more in some effects than in others; but even though the two are so similar in structure, heroin is estimated to be two to six times as strong. Despite these serviceable qualities, importation and manufacture of heroin are forbidden in America, its use for any purpose anathematized. Most American doctors are convinced, largely by hearsay, that heroin is too quickly addictive, and the euphoria it can produce too strongly, even sinfully pleasurable to be safe. Their reference books tell them that better drugs are available for every medical use.

English doctors disagree. Even those who are alarmed about the spread of addiction in their country believe that their American colleagues are stubbornly unprofessional to condone a ban on heroin. They discern at least seven medical uses for it. Among these, they don't defend heroin for coughs with any great conviction. Codeine will really do as well. Soon after taking my spoonful of heroin cough syrup, though, I met a magnificent Englishwoman, Cicely Saunders, whose vocation is the care of the dying. Many of her patients, of course, suffer from cancer. Dr. Saunders has become expert in the control of pain, and also in the control of less obvious causes of extreme distress, such as nausea and the shortness of breath that leads to the sensation of air hunger. She said, and most of her English colleagues agree, that heroin is often the best drug for terminal cancer patients, though she sometimes supplements it with gin. Like morphine, heroin not only blunts the panic of air hunger but can even lessen the fact of it, reducing acute pulmonary edema. Heroin is less likely than morphine to induce nausea. It relieves pain, but more than that, it is uniquely powerful in distancing the patient from what pain he still feels, and from his anxieties. For such patients, addiction is almost inevitable, and almost irrelevant. Yet Dr. Saunders said that their heroin dosages can be well controlled for many months; she will wake patients in the middle of the night to give them heroin so that the pain, and the necessary dose, never get out of control. Intense pain in heart attack is also treated with heroin—again because it freezes anxiety so effectively, as well as pain, and because it is less likely to nauseate. For coronary thrombosis, the need is transitory and addiction unlikely; this use of heroin is increasing. Some English surgeons consider heroin preferable to all other analgesics the night after an abdominal operation. An eminent physician, Henry G. Miller, vice-chancellor of the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, wrote in 1973 that heroin "is an unequalled and irreplaceable remedy for the intense paroxysmal pain that sometimes follows an attack of shingles in the elderly patient, but in many years of its regular prescription I have yet to encounter the patient who failed to return the remaining tablets after the pain had—as it practically always does—finally subsided." Dr. Miller also noted, testily and more generally, that "an unholy combination of neurotic fear of addiction with the traditional Christian glorification of suffering leads a minority of physicians to practice unjustifiable parsimony in the dispensation of pain-relieving drugs (just to be on the safe side, most doctor-patients take their favorite analgesics into hospital in their sponge-bags, together with their favorite sleeping tablets)."

In a conversation with Gisela Oppenheim, a psychiatrist, who runs the drug-addiction treatment center at Charing Cross Hospital, in London, I was told of still another use for heroin in medical crises. As it happens, Dr. Oppenheim has strong views against giving addicts heroin; it was these views I had come to hear. She said she had not prescribed heroin for a new addict patient in three years. Then did she think heroin should be banned in England, as it is in the United States? "Oh, no," she said. "I think heroin is a very useful drug. I worked once in a plastic-surgery ward. We were treating children who had been severely burned. Give them morphine and they might vomit all over. Give them a small shot of heroin and they'd calm down, become less tense—more able to face the visits to the operating theater for dressings. I would hate to see heroin abolished."

Everywhere else in the world, "the British approach to heroin" signifies the other principal medical use the drug is put to: legal, cheap, pure heroin for heroin addicts through government clinics. Before 1968, an addict got his prescriptions for heroin from any general practitioner willing to take him on as a patient. The clinics, where addicts must now come for their prescriptions, were set up only after turbulent debate, touched off by a small but explosive outbreak of new cases of heroin addiction, particularly among adolescents. Inevitably, the clinics are the dominant feature of the British approach as seen from abroad, and the focus of the arguments that continue about heroin at home. Yet in British terms the clinics for addicts and the rules that govern them are a unique limitation of the doctor's powers: it is still true today that—for any patient who is not an addict—any physician practicing in the United Kingdom can write a prescription for heroin and a pharmacist will fill it under the same controls that govern the use of any other strong narcotic. Of the many contrasts between British and American handling of addiction, heroin's place in ordinary British medical practice is perhaps the most arresting.

Ripped from its English context, as it almost always is, the idea of lawful heroin for addicts provokes either advocacy or passionate rejection among Americans who have to deal with the American heroin epidemic. Seen from London in 1968, one exasperating result of the switch from general practitioners' prescriptions to drug clinics was the smug American judgment that the British approach to controlling heroin addiction had proved a failure. At least in the short run the judgment was wrong. So in the past few years American doctors and bureaucrats have streamed over to visit the clinics. More and more often, the visitors have been telling their hosts that the idea of trying out legal heroin for addicts—"you know, the British system"—has acquired political standing in the United States. A current version of that idea is to experiment with cheap legal heroin as a "treatment lure" ( the ugly phrase characterized a proposal made in 1972 by the Vera Institute of Justice, a small New York City foundation that specializes in criminology) to bring addicts in for cure who have failed in other programs. Implicit in all such proposals, and the reason for their political volatility, is the belief that to legalize heroin for addicts more than experimentally would mean that those who can't or won't give up the drug will at least give up the black market and crime.

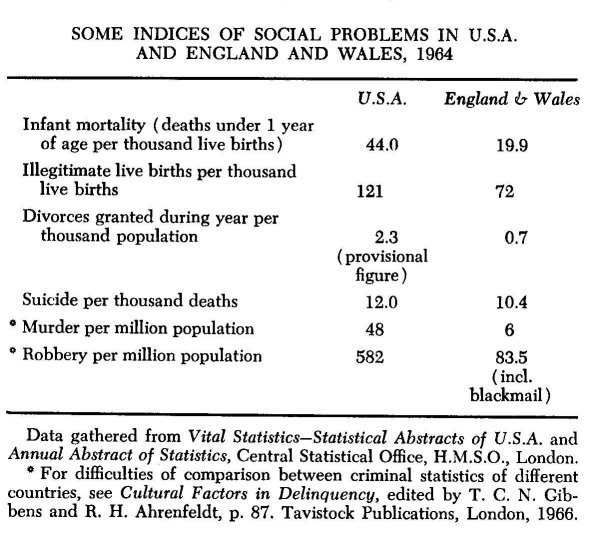

It soon becomes evident to Americans investigating addiction in England—for one thing, their hosts tell them—that the British really have no single, exportable solution. The government counted 1,619 narcotics addicts in Britain at the end of 1972, the latest figure. In Washington, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs estimated in January 1973 that there were 626,000 heroin addicts in the United States, while in New York City alone local officials reckon that there may be a quarter of a million heroin users—or more; they confess they do not know—of whom, more certainly, 150,000 are true addicts. The difference between the British and the American figures translates into huge differences in cost, in the ways addicts interact with each other and with the rest of society, in the organization of medical manpower, in administrative controls, in ethical controls. The difference in scale is so vast—two orders of magnitude, as a physicist would put it—that it all but overwhelms other comparisons and reasonable discussion. That said, it remains true that the British are the only people with a coherent experience of epidemic drug addiction to have dealt with heroin under policies markedly different from those that have long prevailed in the United States. And, whether by policy or by luck (their most thoughtful observers are not sure which), they have so far been successful in containing addiction.

The Maudsley Hospital, a tumble of brown and gray buildings lapped by motor traffic in London south of the Thames, is England's foremost psychiatric hospital for research and teaching. The Addiction Research Unit occupies a two-story prefabricated box in a parking lot at the Maudsley. Griffith Edwards, director of the unit, is a tall, stooped Welshman, ironically courteous to his American visitors—and that old-fashioned delight, a physician with a scholar's sense of the history of his subject. In a conversation a while ago over an institutional lunch—a pale, English institutional lunch of poached fresh fish fillets, broad beans, and stewed gooseberries with custard sauce—Dr. Edwards said, "One wonders how far the differences between the British and American drug problems are really the consequences of social policies. Ab initio, just how much addiction was there in the U.S. and the U.K. in the early '20s, when the very basic differences in approach between the two countries began to take shape? Did the American problem originate much earlier, with the importation of Chinese labor, and so on? Was the heroin problem already a ghetto problem in 1912? Or did it have its origin in the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914, as people say? The relation between a drug and a community can be very unstable—our problem with heroin, barbiturates, and amphetamines may, possibly, be unstable right now. But take the British and alcohol, or India and cannabis—sometimes the relationship is not at all easy to change."

A formula in vogue just now in the United States has it that Americans chose almost from the beginning to deal with heroin addiction by "the enforcement model," while the British chose "the medical model." Modelmakers oversimplify. Both the policeman and the physician have been heard from repeatedly in England, as in the United States. But from the first, the policeman in the United States has been urged on by the missionary—an alliance which has given American narcotics enforcement its characteristic fervor, and which the English have always viewed with distaste. Certainly, and without oversimplification, the international campaign to police the traffic in narcotics has always been led by the United States. The campaign began in the first years of the century, after the Spanish-American War, when the United States emerged as a Pacific power, took control of the Philippines, and discovered the opium trade in those islands and elsewhere in the Far East, especially China. The reaction of American reformers was to persuade Theodore Roosevelt to call for a conference of all nations with interests in the Far East, and then—as a demonstration of American sincerity at the conference—to push through Congress the first federal law limiting the use of narcotics, a simple ban on the importation of opium for smoking, approved in February 1909. The Shanghai Opium Commission convened that same month. Its chairman was the chief of the American delegation, Charles Henry Brent, who had been the first Episcopal bishop of the Philippines. The resolutions of the commission were mild, and dealt for the most part with the suppression of opium smoking and the commerce in opium; one resolution, introduced by the British and unanimously agreed to, said that governments ought to take strong measures to control morphine and other derivatives. The Shanghai Opium Commission was followed, again at American insistence, by the first International Conference on Opium, for which delegations from twelve countries met at The Hague at the end of 1911; Bishop Brent again presided. The conference produced the Hague Opium Convention. Chapter Three of the convention required the nations to control morphine, heroin, any new derivatives that proved dangerous, and cocaine. The United States Senate ratified the convention by the end of 1913, and the Congress was then considering the Harrison Narcotics Bill, but other nations were slower to put the convention into effect. Then the war intervened. However, the Hague Opium Convention has been the basis for international control of narcotics; it was accepted by the British, and nearly everybody else, after it was wrapped into the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Under the Hague Convention, the United States passed its principal law about narcotics six years before the United Kingdom came to it. The Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 was on its face a tax measure, but control, if not prohibition, was its aim, as the congressional hearings on the legislation made clear; the tax, which was a dollar a year, but which required physicians and pharmacists to register with the collectors of internal revenue and to keep detailed records, was merely a constitutional stratagem to preëmpt state regulation of the medical profession. The curious effect, though, was to entrust enforcement of America's national narcotics policy to the Treasury, where it stayed until 1968—and where it was joined for a while by enforcement of the national prohibition of alcoholic drink. The ban on heroin rested on the 1914 act but was not set out there: the Harrison Act said, ambiguously, that a doctor, after paying his yearly tax, could prescribe narcotics "in the legitimate practice of his profession" and "in good faith." Seizing upon this language, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, between 1915 and the '20s, put out a series of ever-tightening regulations, and won a number of court decisions, which defined legitimate medical practice to squeeze American doctors out of giving any kind of narcotic to any addict, whether to maintain his habit or to withdraw him from it gradually. The medical profession, particularly in Illinois and New York, protested almost in the terms of today's debates that addicts were diseased, not criminal, and that the ban was driving them to underworld supplies. Protests failed. In many cities, including Los Angeles and, notably, Shreveport, Louisiana, promising municipal clinics for morphine and heroin addicts were shut down by zealous Treasury Department action. The largest such clinic opened in New York City in April 1919, and had registered over seven thousand addicts by January 1920. That September, the Bureau of Internal Revenue began more strictly enforcing its policy against maintenance of addicts; the relapse rate among those taken off drugs was so discouraging that at the end of the year the clinic's administrators themselves recommended that the New York City clinic be closed. ( The story of these American heroin clinics has recently been set out by David Musto in his book The American Disease, which is the first good history of the origins of American policies about addiction.) Total prohibition of heroin in the United States came almost as an afterthought, with the passage in 1924 of a one-sentence amendment to the Harrison Act, to forbid importation of opium for the purpose of making heroin.

In the years after that, the structure of treaties was repeatedly extended and elaborated, as the international traffic in narcotics increased and as new drugs presented addiction problems, so that, by 1953, nine different conventions, agreements, and protocols had been acceded to by various numbers of nations. In 1961, this tangle was codified and almost entirely replaced by the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. Similarly, and partly in conformance to the proliferating treaties, American law was patched and changed until it, too, was codified—and, in the process, extended—by two federal acts of 1970, the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act and the Controlled Substances Act. These replaced the Harrison Act and moved the Bureau of Narcotics from the Treasury to the Department of Justice; and, though they were illiberal laws—especially the Controlled Substances Act, drafted under the direction of an enforcement-minded Attorney General, John Mitchell—they also quietly rationalized the position of heroin. It is now no longer uniquely prohibited, but is classified as a Schedule I drug, along with LSD and others, with which clinical research is theoretically permitted, with the approval of the Food and Drug Administration and under the strictest controls. The change in heroin's technical legal status has simplified the assumptions of recent proposals to experiment with providing heroin legally to American addicts; but the psychological and political prohibition remains, so far, intact.

The British, once they had acceded to the Hague Convention, drafted control measures promptly. They began not far from where the Americans did. When Parliament came to debate the Dangerous Drugs Bill of 1920, a key issue of enforcement had already been settled in a brisk secret tussle between Sir Malcolm Delevingne, the top permanent official at the Home Office, and his opposite number at the Ministry of Health over which department should be responsible for control of the opiates and cocaine. ( Cocaine, though not addictive and not an opium derivative, is treated just like one under international treaties, and by domestic law in both Great Britain and the United States.) The Home Office—the ungainly ministerial conglomerate that deals with, among many other things, police, prosecutions, and prisons—won the tussle; among its claims Delevingne asserted that "the matter is very largely a police matter." Thus, from the beginning to the present day, responsibility for watching over addiction has lodged primarily with the nearest British equivalent to the United States Department of Justice. The Dangerous Drugs Act, as passed, gave the government broad power to control the manufacture and use of narcotics; early regulations under the Act limited any doctor to supplying such drugs "so far only as is necessary for the practice of his profession." Thus a legal handle very much like the American one was available. It is clear that some people at the Home Office debated grasping that handle. Delevingne pressed the Ministry of Health repeatedly in the early '20s for "an authoritative statement"—one that he could take to court—from the leadership of the medical profession that the regular prescription of narcotics "without any attempt to treat the patient for the purpose of breaking off the habit, is not legitimate, and cannot be recognised as medical practice." Indeed, for a time in those years the Home Office was secretly circulating a list of suspected addicts and doctors to the police. Yet no prohibition evolved.

One reason was the British view of the American experience. It is certainly true that in the 1920s the British set their narcotics policy partly in response to what they saw happening in America—as they did again in the 1960s. Already in the Parliamentary debate in 1920, a backbencher, Captain Walter Elliot, charged that drug addiction was "an evil, spreading, I think, more from the United States than from any other country. It is also very interesting to remember that that is the great temperance country at the moment... . You have this effect, that they have gone in for prohibition and that they have developed the drug habit to an extent altogether unknown in this country." Elliot worked himself up to a denunciation of Americans as "the barbarians of the West" for their "extraordinary savage idea of stamping out all people who happen to disagree ... with their social theories" against narcotics, against alcohol—and in "their recent treatment of Socialists." In January 1923, in The British Journal of Inebriety, Dr. Harry Campbell reported what he had learned on a trip to the United States; there, he said,

a drug habitué is regarded as a malefactor, even though the habit has been acquired through the medicinal use of the drug. . . . The Harrison Narcotic Law . . . placed severe restrictions on the sale of narcotics and on the medical profession. In consequence of this stringent law . . . the country is overrun by an army of pedlars who extort exorbitant prices from their hapless victims. It appears that not only has the Harrison Law failed to diminish the number of drug-takers—some contend, indeed, that it has increased their numbers—but, far from bettering the lot of the opium addict, it has actually worsened it . . . impoverishing the poorer class of addicts and reducing them to a condition of such abject misery as to render them incapable of gaining an honest livelihood.

The warnings were heard.

"One has to see the treatment of the drug problem here in the context of the style in which we carry on the public business," Dr. Edwards told me. "Not only through the government of the day but through the civil service. We have a strong and highly esteemed civil service. It has the capacity and the power to take the long view, beyond the term of one minister or one government. I'm sure, for example, that the initial decision not to go the way of the Harrison Narcotics Act was a civil service decision, which was then accepted by the politicians."

The other force in that decision was the medical profession. The independence of British medicine is truly startling: its jealousy of interference with its standards of practice is that of a medieval guild, and the guild is effectively run by an oligarchy within the profession's top rank—the consultant physicians—who are individually often rich and collectively almost unfettered. The question again is one of style in the public business; the Rolls-Royces in Harley Street are very quiet cars. Americans have been reminded often enough that the postwar Labour government, led on the issue by Aneurin Bevan, socialized British medicine in 1946-47; British observers are likely to recall as well that Bevan could only create the National Health Service by making organizational and financial concessions that brought in—some would say, cast in concrete—the consultant oligarchy. The doctors have shaped British drug policy from its beginnings; in response to the intense, quiet pressure the Home Office was exerting in the early '20s, they quietly but adamantly maintained—as the opinion of the British medical profession—that "morphine and presumably heroin could not in all cases be totally withdrawn from a person addicted to these drugs.... Such an addict required a certain amount of the drug in order to keep him normal."

In 1924, civil servants and doctors got together. That September the government empanelled a blue-ribbon medical committee, under Sir Humphry Rolleston, baronet and president of the Royal College of Physicians, "to consider and advise as to the circumstances, if any, in which the supply of morphine and heroin ... to persons suffering from addiction to those drugs may be regarded as medically advisable." In the next fifteen months, the Rolleston Committee met twenty-three times, taking oral evidence, in private, at seventeen of their meetings, from thirty-four witnesses, who included psychiatrists, apothecaries, a surgeon, general practitioners, professors of neurology, senior civil servants, the medical officers of Brixton and Pentonville prisons, two Scottish alienists, the Director of Public Prosecutions, and E. Farquhar Buzzard, Physician Extraordinary to H. M. the King. The committee wrote a thirty-six-page report, and in January of 1926 submitted it to the Minister of Health, who at the time was Neville Chamberlain. At the bottom of the introductory page was a note: `The cost of this Inquiry ( including the printing of this Report) is estimated at £65. 5s. 6d." The expenditure bought forty-two years of policy.

The report of the Rolleston Committee is, for official prose, a minor marvel: clear, concise, and written in a sedate amble that eats up miles of law, administration, and medical opinion. Sir Humphry Rolleston was known for his energy and exactitude; he was in his early sixties, with a brilliant career ahead of him as well as behind, a man of high Victorian rectitude, patient, courteous, and aloof, with a towering reputation both as a pathologist and as a medical writer and editor. "His literary style, like his handwriting," says his biographer, "was as neat as an etching." His committee defined addiction with a precision that beats any of the other formal attempts I have read: an addict, the report said, is "a person who, not requiring the continued use of a drug for the relief of the symptoms of organic disease, has acquired, as a result of repeated administration, an overpowering desire for its continuance, and in whom withdrawal of the drug leads to definite symptoms of mental or physical distress or disorder." The report anticipated such unpleasant modern insights as that the hypodermic needle itself can acquire a compulsive attraction. It noted, and rejected with cool authority, what in the United States was by then not just medical opinion but the law, laid down in court decisions: that addicts "could always be cured by sudden withdrawal." It recognized that under any method of treatment "relapse, sooner or later, appears to be the rule."

The central issue of policy seems to have been put to the Rolleston Committee most starkly by Delevingne, of the Home Office: the object of medical treatment in cases of addiction must surely be "a steady diminution of the dose, with a view to its ultimate complete discontinuance." If so, wasn't the fact of continued administration in undiminished doses "evidence, prima facie, that the drugs were not being administered solely for the purposes of medical treatment"? No; the committee concluded that there were people "to whom the indefinitely prolonged administration of morphine or heroin may be necessary: those in whom a complete withdrawal of morphine or heroin produces serious symptoms which cannot be treated satisfactorily under the ordinary conditions of private practice, and those who are capable of leading a fairly normal and useful life so long as they take a certain quantity, usually small, of their drug of addiction, but not otherwise." Diagnosis of such need was up to the individual doctor—although he might not want to deal with such cases at all, and if he did so, he was warned, he would be wise to protect himself with a second medical opinion.

It is a fifty-year paradox that the American "enforcement model" chases after what is precisely a medical absolute—the seeming truth that cure should be the object, which means getting the addict off heroin—while the British have supposed that treatment of the addict, though exclusively the responsibility of doctors, should be predicated on a realistic view of what can and what cannot be enforced. For decades, such realism has been repeatedly excoriated by American officials responsible for control of narcotics; recently, for example, it was denounced as expediency, weakness, and surrender by, among others, the Director of the federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. But the report of the Rolleston Committee, when one reads it half a century later, has in fact the flavor of an almost Johnsonian conservatism, the sort of muscular pessimism that succeeds in being compassionate. The committee were the more able to be compassionate because—as the report said with an air of surprise—the evidence "is remarkably strong in support of the conclusion that, in this country, addiction to morphine or heroin is rare." No reliable estimates exist for the number of addicts in the early 1920s, either in England or in the United States. It is often said, by averaging everybody's guesses, that when it became illegal to prescribe narcotics to addicts in the United States, two hundred thousand people were affected—one in every five hundred. In Great Britain in 1925, while the Rolleston Committee was deliberating, thirty-five people, almost all of them Chinese, were prosecuted for the use of opium, and thirty-three people were prosecuted on charges of illegal use of morphine, heroin, or cocaine; the British population was then forty-five million.

At times of great public anxiety about drugs and addiction—whether, for example, over opium smoking in the Far East in the nineteenth century or over heroin in the United States since the Second World War—the addict has often been seen through the wrong end of the telescope, separated, distanced, and diminished, as though in the grip of a force, the drug itself, that relentlessly destroys his body and degrades his moral independence. He is seen as an automaton, winding down. At such times, some addicts come to see themselves that way. The Rolleston Committee was a group of eminent doctors, hearing evidence for the most part from men of their own kind; they met at a time when public concern about addiction in England was not high. The addicts they envisioned, "to whom the indefinitely prolonged administration of morphine or heroin may be necessary," were not winding down, but stable—and stable more than in their daily dose, but socially stable, in their daily lives. The idea of the stable addict, defined if not named in that celebrated brief passage, has been the most durable contribution of the RoIleston Committee to the British approach to narcotics. Among their many other conclusions, two issues of administration concerned them. They heard strong suggestions that doctors be required to report new cases of addiction as they do the notifiable plagues like smallpox; the committee concluded that the idea was an uncalled-for violation of "the confidential character of the relation of doctor and patient." So compulsory notification was not established. The committee also considered whether there ought to be a way for the Home Secretary, when a physician was abusing the right to administer or prescribe narcotics, to take away that right without more drastic action like taking the man to court ( which would mean "public odium," medically unqualified magistrates, and irrelevant sentences) or taking him before the profession's governing body, the General Medical Council ( whose only disciplinary recourse is to disqualify the doctor from practice altogether). The committee concluded that a permanent medical tribunal should be constituted to judge such doctors and recommend restrictions on their right to prescribe. But the idea lapsed and the tribunals were not set up. Compulsory notification and medical tribunals both reemerged in the 1960s.

For many years, perhaps since the time of the Rolleston Committee, one important fact about the rights of the addict in Britain has been misunderstood. There has been an almost indestructible belief that the addict can be in some way centrally "registered" with the government, after which he is legally entitled to be maintained on his narcotic. That has never been true—though the legend has caused many a newly hooked English adolescent a jolting descent to earth, and regularly confuses visitors. A recent example of the confusion appeared in Licit and Illicit Drugs: The Consumers Union Report, a sensible book that nonetheless says, of those English addicts maintained on methadone at the present day, "Any one of those patients can at any time decide to go back to heroin and have a legal right to get it," which is the reverse of the fact. The essential point is that choice of treatment was always the doctor's; it still is. The English "registered addict" has never existed. The Rolleston Committee had rejected the idea that doctors should be required to report cases of addiction; but the Home Office civil servants were still left with the duty of preventing the illegal diversion of narcotics from medical use, and on them also devolved a treaty obligation to report once a year to the League of Nations ( and now to the United Nations ) on the extent of addiction in the United Kingdom. For this supervision a Drugs Branch was set up in the Home Office in 1934. The Drugs Branch relied on only one compulsory source of information: the records of all deaIings in narcotics and other strong drugs, including prescriptions filled, which must be kept by retail pharmacists, and which are inspected by the police, stopping by unannounced at least twice a year. In London, four men from the Metropolitan Police check pharmacies full time. The pharmacists' records reveal the identity of any patient getting morphine or heroin regularly for long, and who his doctor is. The system was explained to me this way: "The average terminal cancer case only lasts about three months; to avoid picking up those, the police had instructions to report any case of regular supplies that had been going on for six months or so. The Drugs Branch then had an arrangement with the Ministry of Health, which has regional medical officers around the country, themselves doctors. One of these would go along to discuss the case with the prescribing doctor and report back—either that it was a case of genuine medical need or that it was now a case of addiction." Police and prison doctors, too, would let the Drugs Branch know whenever they came across an addict, and so did some general practitioners voluntarily.

New cases of addiction, suspected or confirmed, were listed in an index by the Drugs Branch. If other details about the case could be discreetly gathered, they were added. The index was begun in rudimentary form sometime early in the 1930s, and is still maintained. It is a record unique in the world—unique as a virtually total enumeration of a major nation's experience with a major social problem during nearly half a century, and unique, too, as an embodiment of governmental self-restraint. The index has been the essential starting point for several studies of addiction. It seems to have been kept with scrupulous care for the addicts' privacy. It has itself been the subject of learned articles. The index is maintained by five government clerks in a cluttered room, and is nothing more prepossessing than six stacks of card files, two of them newer than the others, set on corners of a desk and a table. Each addict's card shows at least his name, his aliases (if any) and address (if known) , his age and physical description, the drugs he has been reported to take, when he started taking them, and where and when he was first reported. Many reports turn out to be repeat sightings. Each new addict is given a number.

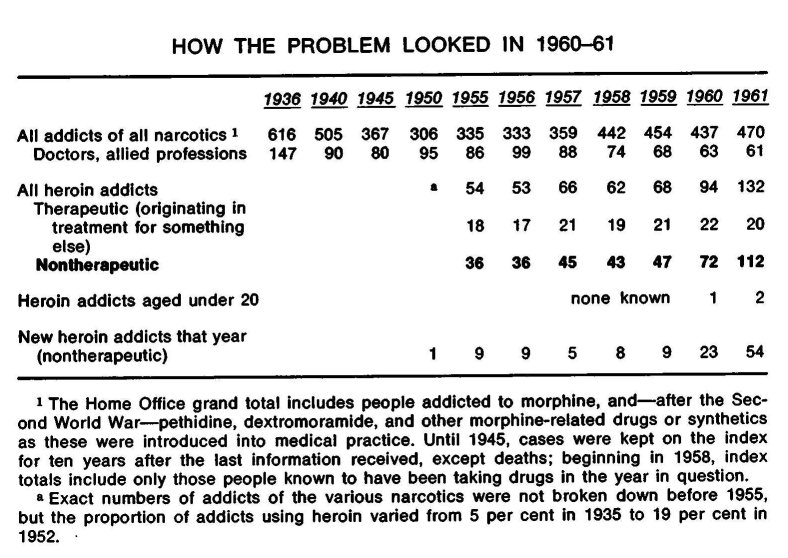

In 1936, the first year the records included much detailed analysis, just 616 addicts were known to the Home Office. Nine out of ten were addicted to morphine. One in twenty was on cocaine, one in twenty was addicted to heroin. Most of the addicts had acquired their habits in the course of medical treatment for something else. Almost half were women. "In the nature of things, the addicts were usually in the fifty-plus age group, they were scattered through the country in no contact with one another, and in fact were no problem whatsoever," I was told. "Often, the addiction was a secret even from the addict's husband or wife. An addict was known as such only to his doctor, and to two civil servants and a clerk." One hundred forty-seven of the addicts were themselves doctors. By 1953, the number of known addicts of any narcotic had dropped to 290. Not since the First World War had there been any sign, either from addicts or through customs seizures, of systematic smuggling.

The extraordinary fact is that heroin addicts were so few up through the 1950s that one man at the Home Office was able to know most of the nontherapeutic cases personally, and to follow, individual by individual, incident by incident, the epidemic of heroin addiction that developed over the next fifteen years. The Drugs Branch takes up a corner of one floor of a large building in Westminster, where the corridor walls are lined with a linoleum-brown stone identified by a chiseled inscription as "British marble." From there, the branch deals with drug manufacture and trade; it has been headed by a succession of rising civil servants, but two key men have been there since shortly after the war. The first is Charles G. Jeffery, now Chief Inspector, a compact, graying man, who despite his title and a certain hardness of palm is not any kind of policeman; he inspects the pharmaceutical industry. The second, in the office next door, is Deputy Chief Inspector H. B. ( Bing) Spear, who has a youthful unlined face, pale hair, and pale eyes; on his wall is a map of London stuck with pins showing the offices of doctors suspected of overprescribing drugs such as, most recently, amphetamines and barbiturates. From October 1964 to the summer of 1972, their immediate boss was Assistant Secretary Peter Beedle, a tall, jovial, subtle man, who perhaps epitomizes what is meant by the capacity and power of the British Civil Service to take the long view. Not all of Beedle's attention was given to narcotics; among other things he was concerned with cruelty to animals and the protection of wild birds. By civil-service rule, these men may not talk for quotation. Both Jeffery and Spear, however, have published professional reports on the rise in addiction; a score of sources in London confirm and amplify what they say.

Outside the Home Office, Spear is described as the man who for nearly two decades carried his own index in his head; even in the late '60s, when addiction was rising rapidly, he knew the addicts so well, I was told, that when a doctor with a new case telephoned him, Spear would listen to the physical description, ask a couple of questions, and identify the addict, giving his real name, his previous physician, the size of his usual prescription, the particular group of addicts he belonged to, where he lived, and, often, the girl he was living with and the person who had given him his first shot of heroin. What was even more remarkable, addicts looked on the Home Office as friend, confidant, and ally, turning to the Drugs Branch when they were in trouble with the police or at work, say, or for help when they were defeated by the social-welfare bureaucracy—or simply to find a pharmacist outside London where prescriptions could be cashed on a holiday. The strict American parallel would be a Washington addict's coming in off the street to ask one of the assistant directors of the Drug Enforcement Administration ( latest reorganization of the Bureau of Narcotics) for help in dealing with the landlord. The increased number of addicts in England today and the development of the clinics make this kind of individual contact less easy and less necessary; yet it still happens, and English addicts, though they dislike and distrust the police nearly as much as addicts anywhere—for one thing, British laws against marijuana are toughly enforced—still regard the Home Office Drugs Branch highly.

About 1950, the only heroin addicts in England whose addiction was not an accidental result of medical treatment or who were not themselves doctors or nurses made up a circle in London of no more than twenty-five. Most of these had picked up the heroin habit abroad. Several were socially prominent. They were always able to find one or two private doctors willing to ignore the ethical questions of cure, of second opinions, of minimum doses. They did not proselytize. Their number had remained steady for years. In 1951 came the first sign of increase—the warning temblor that rattled the teacups and set the chandeliers to swaying. That year, on the night of April 24, a young man named Kevin Patrick Saunders, who came to be called Mark, and who had been employed in the pharmacy of a hospital just outside London, returned there, broke in, and stole 3,120 heroin tablets, 144 grams of morphine ( over five ounces ), and two ounces of cocaine—drugs worth, at cost, the equivalent of a hundred dollars. Before Scotland Yard arrested him, in September, Mark had peddled most of the heroin and cocaine around the jazz clubs that had grown up in Soho. Of those Mark ultimately infected, twenty were jazz musicians, and a number were black, including six Nigerians. From a notebook he carried, full of initials, the police were able to list fourteen people who had bought directly from Mark. Only two were already on the index. Over the next several years, the remaining twelve presented themselves to doctors as addicts, as did a lot of their contacts. Spear has traced the addiction of sixty-three people back along the transmission tree to Mark. Some were soon in jail; some left the country; a few quit; several disappeared; within a few years seventeen died, often nastily.

The stolen cocaine was bought by some of the same people who bought the heroin. Cocaine is a violent stimulant, with few and circumscribed medical uses. Taken simultaneously with heroin, as Mark's customers used it, cocaine is said to counter heroin's depressive effects and add zing to the euphoric high. The use of drugs in multiple and bizarre combinations, frequently switching from one to another, has marked the English epidemic from the start, though "poly-drug abuse" ( current medical jargon on both sides of the Atlantic) has figured in the States only in the last few years. But even with Mark's customers trickling through the index, in the early '50s the number of heroin users whose addiction was nontherapeutic—that is, not a by-product of medical treatment for something else—climbed no higher than thirty-seven known in any one year.

Then, on 18 February 1955, Major Gwilym Lloyd-George, son of a famous father and Home Secretary in Anthony Eden's Conservative government, replied to a Parliamentary question from a backbencher that the current licenses to manufacture heroin, when they expired at the end of the year, "will not be renewed. After that date licences will only be granted for the manufacture of such small quantities as may be required for purely scientific purposes and for the production of nalorphine." No further exports of the drug were to be authorized, either. But since the importation of heroin had been prohibited, as an elementary control measure, for many years, the announcement—though it mentioned directly neither addiction nor the drug's use in general medicine—signified that heroin was to be banned. The new policy would mean replacement of the medical view of heroin and its dangers by an unemphatic, British variant of the international enforcement approach. After ten months of increasingly rancorous controversy and a thrilling denouement, the policy proved to be no more than a digression; and yet the controversy fixed the nature of the British approach to heroin much more firmly than before.

To the government, the proposed ban did not seem at all momentous. Heroin, after all, was a drug of minor utility and evil reputation. The fact that a number of countries still permitted the manufacture of heroin and its use in medicine had been for years an irritant to the

the bureau's commissioner, Harry J. Anslinger, had held his post since it was established in 1930, and was a fundamentalist about stamping out the drug menace. Partly under American pressure, academic medical opinion internationally had been drifting toward the view that so many new substitutes were available that heroin was not irreplaceable. English medical opinion certainly appeared to be following this drift. In 1950, the British Pharmacopoeia Commission had concluded that the alternative drugs were suitable; after checking with the British Medical Association and the Medical Research Council, they dropped the entry for diamorphine in the 1953 edition of the Pharmacopoeia. Several times, the latest in July 1953, The British Medical Journal published articles about heroin clearly sympathetic with the idea that there was "an a priori case for its total abolition"; the 1953 article drew one solitary letter of protest. Meanwhile, Anslinger was pursuing his campaign through the United Nations and its various specialized agencies. In 1953, the sixth World Health Assembly—W.H.A. is the parliament of the World Health Organization—met in Geneva and among its business resolved, in response to the American lobbying, that "the abolition of legally produced diacetylmorphine ... would facilitate the struggle against its illicit use." Next, in 1954, the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs, on which Anslinger himself served as the American representative, voted that all countries should be asked to ban heroin. The British delegate abstained, but said he thought the United Kingdom would consider the request favorably. Then the question moved up the organization chart to the Economic and Social Council of the U.N., who resolved the same way.

In retrospect, the British government's acquiescence seems almost absent-minded: the formal machinery of policy making was switched on, but nobody was watching it. Iain Macleod, Minister of Health at the time, first asked for the opinion of the government's all-purpose Standing Medical Advisory Committee, which included Edward A. Gregg, chairman of the Council of the British Medical Association, two other B.M.A. leaders, the president of the General Medical Council, and the presidents of the Royal College of Physicians and the other collegiate organizations of specialists. The Standing Medical Advisory Committee, when the question was put to them in innocent-seeming but narrow form, whether heroin was indispensable, replied unanimously that adequate substitutes were available. So Macleod told Major Lloyd-George and the rest of the cabinet that the Ministry of Health found no obstacle to Britain's conforming to the U.N. resolutions. Thus, out of a combination of international pressure and domestic indifference, the decision was reached that after the end of 1955, the Home Office would issue no more licenses to manufacture. New legislation was unnecessary. When stocks ran out, the use of heroin would cease.

The government was completely unprepared for the doctors' reaction. An extraordinary battle now began. Senior physicians denounced the ban—as astonishing and iniquitous, as sure to produce "much hardship to a multitude of patients," as interfering with treatment of addicts by gradual withdrawal from heroin, as an unprecedented infringement of the liberty of medicine. Letters in the medical weeklies derided the supposition that the heroin legitimately manufactured in Britain had any effect on the world's illicit traffic. The list of pains for which heroin was of peerless value grew longer. Many hospitals and general practitioners began stockpiling heroin for years ahead. Macleod insisted in the Commons that he had consulted medical opinion as he was required to do, but now many doctors said that the Standing Medical Advisory Committee could not speak for the profession. On June 3, the annual meeting of the British Medical Association passed resolutions by large majorities calling for the manufacture of heroin to continue. Dr. Gregg, chairman of the B.M.A.'s council, had concurred in the advice of the year before; now Gregg said that of course he was not on the Advisory Committee as a representative of his association. Gregg led a deputation from the B.M.A. to see Lloyd-George and Macleod on July 11. Privately, ministers and their civil servants were furious that the leaders of the British Medical Association, as well as other advisers, had switched sides. On October 17, Macleod wrote the B.M.A. that the decision was irrevocable. Next, the twelve London teaching hospitals announced that they unanimously opposed the ban. The newspapers seized the issue and took the doctors' side, from The Times to The News of the World. On Monday, December 5, Macleod was put to the question in the Commons; conceding only that "this decision is a desperately difficult one for a government to take," he asserted over and over again that medical opinion had been consulted and that the prohibition would stand. On Thursday, Lloyd-George, less eloquent, was as adamant.

Five days later, on December 13, the prohibition was abandoned. That day the House of Lords was scheduled to debate a motion, put down a while before by Earl Jowitt, that the current licenses to manufacture heroin should be extended beyond December 31 until the conflict of medical opinion was resolved. Under British constitutional arrangements, the House of Lords' true importance is now as much in the judicial as in the legislative function. The Lords have been almost totally stripped of effective legislative powers, so that what is said there about bills to be passed is not often consequential; but among their members are the Lord Chief Justice and the other justices—the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary—who make up the nation's highest court of appeals, while the Lord Chancellor, who presides over that highest court as well as over the House of Lords, is the most eminent legal officer of the government of the day. Retired Law Lords remain peers. ( It is as though the present and retired members of the U.S. Supreme Court were automatically members of the Senate. ) It was a legal argument that unexpectedly routed the government. Somebody, over the weekend, suggested to Lord Jowitt—himself a former Lord Chancellor—and the British Medical Association that they consider the exact language about licensing in the Dangerous Drugs Act. Who transmitted the suggestion has never been acknowledged; almost certainly the point originated with a civil servant inside the Home Office, who had noticed that the Act gave the Home Secretary licensing power as a means of controlling manufacture of the drug, but not, after all, in terms that could be stretched to include total prohibition. The day before the debate, Jowitt took up the question with the then Lord Chancellor, Viscount Kilmuir, who agreed. Lord Jowitt opened the debate. "There is very serious ground for doubting ... whether the Home Secretary has any right to use this [the existing] Act as a vehicle for bringing about this ban," he told the peers. "If that is said to be a method controlling the manufacture to prevent its improper use, all I can ask is whether, if I were in charge of a horse, a dog or a child, and was told to control it, and I shot it through the heart, though it would lie still and give us no further trouble—should I really be controlling it?" ( There were cheers.) The ban was beyond the powers of the Home Secretary; prohibition, Jowitt thought, would require a separate, new bill. He and the peers who followed then debated at full length the doctors' case against the ban. And if that was anticlimax, at times it was splendid: Lord Haden-Guest said that he had not been afraid on the battlefield, "There is too much girning and sob-stuff about death by cancer—I speak at the moment as a doctor," heroin was not the only way to relieve pain, and "Do you suppose we had heroin in the First World War when we were fighting in France?" Lord Teviot said that many peers were shocked greatly at Lord Haden-Guest's references to the First World War, and that "he should have seen some of the things that I saw in the dressing stations and the forward hospitals in the First World War, he would have wished to God we had had heroin to help us then!" Lord Amulree intervened to say that he had hardly ever used heroin in his hospital work, but had used it a lot on himself when he got one of his nasty coughs, which were intractable; he had tried substitutes, but "I like my little drop of heroin: it works very well for me"; he had taken it for twenty-five to thirty years but had not yet become an addict. ( There was laughter.) Even while they spoke, the government were deciding that Jowitt's legal question was crucial, and that they would lose, embarrassingly, if the matter came to a vote. At the end of the debate, Viscount Woolton announced for the government that the licenses would, after all, be issued after December 31. Prohibition of heroin was never pressed again. The drug resumed its place in the British Pharmacopoeia. At a time when addiction was not a domestic problem, the government was reminded of what it should never have forgot about dealing with the medical profession, and the doctors rediscovered how they valued their professional liberties and what they really thought about the medical uses of heroin.

By 1959, the number of nontherapeutic heroin addicts on the index had crept up to forty-seven. Meanwhile, three decades and a war after the Rolleston Committee, another medical panel, with another physician-baronet, Sir Russell Brain, for chairman, was asked by the Macmillan government to look at habit-forming drugs anew. The Brain Committee labored under handicaps. Their instructions were very broad: to consider the possible abuse, not just of morphine and heroin ( as the Rolleston Committee had done), but of newer, related strong analgesics, and beyond these they took on barbiturates, amphetamines, and even tranquilizers. Worry about misuse of these drugs was justified—for example, the amount of barbiturates prescribed in England had almost doubled between 1951 and 1959—but, as it turned out, the Brain Committee were both distracted and indecisive in their consideration of so many problems. Then, too, they worked with neither the urgency nor the exceptional common sense of the Rolleston Committee. Strangely, although senior officials of the Home Office were in close touch with the Brain Committee, nobody in the Drugs Branch inspectorate gave evidence. The committee felt no need to question the general complacency of the British medical profession about the control of heroin. As one man told me with remembered bitterness, "They said that everything in the garden was lovely." Indeed, the committee said, in particular, that there was "no cause to fear that any real increase" in addiction was occurring, that most addicts were stabilized, and that, although there had been two doctors in the previous twenty years who had prescribed carelessly or in excess, "in spite of widespread inquiry, no doctor is known to be following this practice at present." While they reminded their colleagues to get a second medical opinion before treating an addict, they strongly rejected any revival of the Rolleston Committee's plan for special medical tribunals that could discipline a doctor by withdrawing his right to prescribe. They saw no need for specialized centers for treatment of drug addiction. In this fashion, the Brain Committee missed the first detectable signs of trouble: it took two and a half years to produce a handwringing document that plumped for no change.

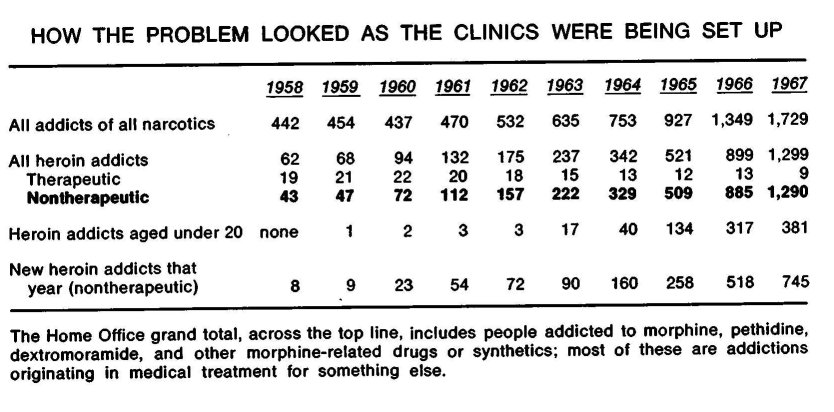

On the evening of 18 April 1961, with the report due out in a few weeks, Sir Russell Brain gave a preview of the committee's findings in a talk before a closed meeting of the Society for the Study of Addiction, in London. The timing could not have been more embarrassing. Though the numbers were not yet public, nor even known to many in Brain's audience of specialists, the fact was that in the previous year non-therapeutic heroin addiction had risen sharply: twenty-three new cases making a jump of 53 per cent in the total. Among these was the first case under the age of twenty. In 1961, heroin addiction was rising even faster, and by the end of the year there were nearly twice as many new cases as in 1960, bringing the total to 112 known addicts. They were almost all in London; the custom had begun for an addict, late in the evening, to take his prescription dated for the next day to one of the two pharmacies in London that stayed open around the clock, where he would wait with his mates for midnight. The junkie coven at Boots the Chemists in Piccadilly Circus became a grisly tourist attraction and was parodied in films. In Brain's audience at the Society for the Study of Addiction was a pharmacist, Irving Benjamin, who worked at the other all-night shop—John Bell & Croyden, Wigmore Street. Benjamin had kept his own card file with data on each addict who came in with a prescription. After Sir Russell's anodyne assurances that there was only a small and apparently diminishing number of addicts, "scattered about the country," and a negligible illicit traffic in their drugs, Benjamin stood up. As one who was there described it, "Benny caused a little bit of a hoo-ha."

"Sir Russell's optimism amazes me," Benjamin began. "A short while ago, I came across an addict who was completely unknown to the Home Office. He presented his prescription to a shop for something like thirty grains of cocaine [ 1,800 milligrams] and forty to fifty grains of heroin. That was repeated on several different occasions, in several quantities. This was prescribed by a doctor who I know for a fact was making every effort to treat these people.... That patient had obviously been obtaining supplies illicitly on such a scale as to get used to those quantities.... As to the suggestion that there seems to be no large center of addiction, I personally can record forty or fifty cocaine, heroin, and morphine addicts in the London area alone."

The problem that alarmed Benjamin was indeed becoming a medical scandal; over the next eight years, as the scandal ran its course, the lives of a thousand patients were wrecked, many died, and several doctors were ruined. "Anybody who goes to an illegal source for his drug is a fool," another man called out from the floor of the meeting where Benjamin spoke. "There cannot be a very big black market in Britain, simply and solely because the laws are as they are, and not as they are in America." But that was the last protest of complacency, for, in fact, one consultant at a drug clinic recently recalled, "It was perfectly possible then to maintain a habit at a modest financial outlay without having to go to the doctor oneself." New addicts were buying drugs from other addicts who were getting them, sometimes in unbelievable quantities, on prescriptions from general practitioners: the prescription system, which in the past had always kept the heroin supply in balance with the demand, so that a black market had nothing to feed on, had now become the only source of heroin for a black market so virulent that over one stretch the number of heroin addicts on the Home Office index was doubling every sixteen months. And for the first time there was real fear that the index was missing many addicts.

The reasons for the English heroin epidemic are still bitterly argued, for they are by no means altogether clear. Blame has been shared out among the doctors who were prescribing to addicts; the rest of the medical profession, who turned their backs on the incipient problem; the addicts themselves, who were a type that doctors had not had to deal with before; the other drugs adolescents were taking, or that their parents were taking; television and the press, for publicizing those drugs; and the more fundamental revolution in youth's customs, beliefs, roles in the social order, and powers of influencing each other which was going on ( apparently in all industrialized countries ) in the 1960s. Any halfway satisfactory accounting of the English epidemic promises help in interpreting the social mechanisms in other drug crazes, like the amphetamine plague that swept Japan in the '50s or the manic use of stimulants that still afflicts some groups of young Swedes; and, obviously, the English heroin epidemic rightly understood should illuminate, if only by contrast, the American heroin problem. More than that, only by disentangling the causes of the English epidemic can one come to see clearly how it was at last brought under control.

The English argument begins—though it doesn't end—with the doctors in the '60s who were writing prescriptions for addicts. They were the first and easiest to be attacked, because they were the most visible. Some of them were obviously culpable. Even now, the names of the "prescribing doctors" are mentioned reluctantly by officials or by colleagues who observed what was happening. Ten or twelve doctors were implicated at one time or another. Their motives varied. Most were in private practice rather than in the National Health Service. A few were venal, selling the prescriptions for cash to anyone glib enough who came to their offices. One was a compulsive gambler, who after a bad day with his turf accountant was known to make house calls on addicts. Another is now in Broadmoor, the English hospital-prison for the criminally insane. Some were warped by the special relationship with patients which heroin makes possible: there were incidents, reported by psychiatrists who inherited the patients, of addicts forced to crawl across the room on their bellies to get their prescriptions. And a few of the prescribing doctors were dedicated physicians attempting to treat patients that most doctors refused to touch. The Drugs Branch often tried to warn doctors off, but whenever one doctor dropped out, the addicts swarmed to another. Over the years, the Home Office and the most active or conscientious of the prescribing doctors developed a collaboration: the doctors helped keep up the index, and the inspectors stayed in touch with the network of addicts as the infection spread.

The insidious role that doctors' motives can play in the treatment of drug addicts is a theme that runs through the British experience to the present day. The problem is now becoming evident in the United States, too, with the growth of methadone-maintenance programs; in the past couple of years several privately run treatment centers, in New York, Chicago, and elsewhere, have had to be shut down because the physicians in charge began handing out methadone in large amounts, indiscriminately. What can be involved when a doctor prescribes narcotics was suggested in the course of a conversation I had with Martin Mitcheson, a bearded, engagingly quizzical psychiatrist, with a law degree as well, who runs the drug-dependence clinic at University College Hospital. Dr. Mitcheson was on the telephone as I came in, evidently talking with a court official about one of his patients. "Not much possible for a year or two yet," he was saying, with clipped concern. "I'll just have to grip the arms of my chair and hope she turns up ... using the prescription as some kind of control. ... I'm sure she will go back to prison, but I think that this is a bad case to recall her on." After he hung up, we began by talking about the incidents of the early '60s. " `The Psychopathology of the Prescribing Doctor'—that's a paper that will never be written," Mitcheson said. "And one reason it won't be written is that I am on the same continuum as those doctors were—though, one hopes, in a less extreme position. But I am in a position with a great deal of power. For instance, that phone call just now was about one of my addicts, a girl I am keeping out of prison on this occasion. But after that she is not going to get her prescription unless she goes through certain hoops for me. The control that prescribing offers, on top of the relationship that develops with a patient anyway—as a psychiatrist one has a duty to be aware of this. And maybe one can use it a bit. But some of the prescribing doctors, I think, were totally out of control of their own psychopathologies—completely at their mercy—and did the most dreadful amount of harm."

One of the first and most notorious of the prescribing doctors was Lady Isabella Frankau. She had a private practice in Wim-pole Street, is said to have been moderately successful in treating alcoholism, and certainly did not need to work with addicts for any reason like the money in it. Among her earliest drug patients were a number of the jazz musicians—including several of the Nigerians—who had become addicted in the '50s; Lady Frankau was a principal instrument in pumping that group up into the fulminating heroin outbreak of the '60s. She dominated the personal lives of some of her patients. Such domination is essentially ambiguous. "Addicts are motivated, highly manipulative, lying psychopaths," one doctor told me. "Lady Frankau was hoodwinked." In 1960 she and a colleague published a paper in The Lancet on the treatment of drug addiction, in which they reported cases maintained on heroin and cocaine during an extended preliminary period of psychotherapy before withdrawal was attempted. The paper spoke with ominous naïveté about prescribing to addicts:

A minor difficulty during this period was their inability to say simply that they had overstepped the usual amount. Instead they either augmented their supplies from the black market, or produced plausible stories of accidents or losses. Eventually they realised that it was better to state bluntly that too much had been used. Extra supplies were prescribed to prevent them returning to the black market, which would involve them in financial difficulties, and (which is even more important) would mean a return to the degradation and humiliation of contacting the pedlars. . . . During this phase of treatment the patients acquired enough insight into their condition to be able to cooperate.

"Extra supplies" brought some of Lady Frankau's patients up to 1,800 or 2,400 milligrams of heroin a day, and while some were really injecting nearly that much a day—a three- or even six-month supply for an American addict—most were pushing out the surplus. In 1962, Lady Frankau alone prescribed six kilograms of heroin: more than thirteen pounds.

John Hewetson and Robert Ollendorff, in contrast, were in general practice together, not privately but under the National Health Service. They had had three or four addicts among their patients for several years, so they later wrote in The British Journal of Addiction, and from them learned "that there were a vast number of addicts who were able to get their prescriptions privately, but who were frightened to bring their addiction problem to their [N.H.S.] general practitioner, and who therefore bought their drugs on the Black Market." Believing that their colleagues were making it impossible for addicts to get care under the National Health Service, to which they were entitled like any other patient, Hewetson and 011endoríf decided to take on any genuine addict who came to them. Within six months they had nearly a hundred. Their account makes vivid the exasperating irritations that doctors met, and the risks they ran, in trying to treat addicts in such numbers as part of a general practice: the addicts' incessant demands, the ever-repeated mindless search for the next fix, the tantrums in crowded waiting rooms, the high rate of sickness, the endless night and weekend emergencies. "Clearly the work involved is so great that normally the general practitioner in a busy practice would be unable to cope with it at all," they wrote. Even for doctors with the soundest motives, a hundred heroin addicts create pressures that after a while distort judgment.

By the end of 1964, the index carried 329 nontherapeutic addicts, 160 of whom had been added just that year; 40 were under the age of twenty, including one child of fourteen. In 1965, the total jumped to 509; in 1966, to 885, more than 300 of them under twenty. Not only the rate of increase but the actual numbers began to look scary. The prescribing doctors were blamed by the press and in official inquiries. But clearly that blame was too indiscriminate. "None of those doctors were getting any help," I was told by one official who had known them. "They weren't even getting the backing of hospitals. I mean, if you want to level a criticism it must be at all the rest of the profession, who were not prepared to take their share of the load." This observation marks about the furthest point that any public analysis of the problem had reached by the mid-'60s. The change to addiction clinics was designed expressly and narrowly to put prescribing general practitioners out of the heroin business, to shift the responsibility for maintaining addicts to a more controllable part of the medical profession, consultant psychiatrists, and to give those who were now to be dealing with addicts some formal institutional supports—a hospital setting, regular touch with professional colleagues.

Only one English doctor who was treating addicts in general practice during the mid-'60s is still in the field. He is Peter Chapple, a psychiatrist, whose careworn and comfortable manner belies the fact that he has long been bitterly critical of English drug policies. Dr. Chapple has turned against heroin for addicts; he now runs two programs, one using methadone and the other requiring total abstinence, in the part of London that has been known since Restoration days, with reason, as World's End. Looking back, in conversation, Chapple said, "There were several very disturbed doctors dealing with the addicts. Yet the campaign against the doctors was unfair, for there were also one or two very good men, quite skillful at handling addicts, among the general practitioners. Everybody was naïve, thóugh; we all did all sorts of silly things. But was it really the prescribing doctors who created the problem? Or was it in fact that we were getting a new type of addict, who had come from a very different place?" His questions open up the next layer of the problem: in the interaction between prescribing doctors and their addict patients in the '60s, the big change was not in the doctors—addicts had always found doctors—but in the addicts.