CHAPTER SIX LSD AND THE SACRED MORNING GLORIES OF INDIAN MEXICO

| Books - Hallucinogens and Culture |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER SIX: LSD AND THE SACRED MORNING GLORIES OF INDIAN MEXICO

For Dr. Albert Hofmann of Sandoz Ltd., a well-known Swiss pharmaceutical house headquartered in Basel, his finding in 1960 that the psychedelically effective principles of morning-glory seeds were nothing else than lysergic acid derivatives, closely related to synthetic LSD-25, was, as he wrote later, like "closing a magic circle" on a research series that began more than twenty years earlier with the discovery of LSD and that finally embraced some of the most interesting of the divine hallucinogens of Indian America.

LSD and Parkinson's Disease

In a very real sense the circle is also closing with respect to Hofmann's hope, expressed at the time of his epoch-making discovery of LSD, that because of its ability to mimic certain mental illnesses the drug might prove useful in their treatment. In fact, LSD has been employed to that end over the years by some psychiatrists, often with beneficial results. However, the potency of LSD and the severe legal limitations imposed in recent years on its use even under controlled scientific conditions have caused psychotherapists to turn to other chemical agents, such as those discussed in a previous chapter.

Recently, however, scientists at the School of Medicine of the University of California at Los Angeles have made some significant discoveries about the interaction of LSD with dopamine, one of the neurotransmitter agents in the brain, that may lead not only to a better understanding and eventual treatment of schizophrenia, the mental disorder to which the LSD "high" is a kind of temporary analogue, but even of such physically, rather than mentally, crippling disorders as Parkinson's disease (UCLA Weekly, 1975:4). The investigators, Drs. Sidney Roberts and Kern von Hungen and Diane F. Hill, determined that adenyl cyclase, an enzyme in nervous tissue that is stimulated by naturally occurring neurotransmitter agents, is also stimulated by the action of LSD on receptors for one of these neurotransmitters, dopamine. In addition, LSD blocked the stimulatory actions of dopamine and other neurotransmitters (agents that aid in conducting impulses along nerve cells, specifically bridging the gap, or synapse, between them), such as serotonin and norepeninephrine. These, as noted in the Introduction to this book, are themselves structurally closely related to powerful plant growth hormones; dopamine, moreover, has also been identified with the giant saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea) of Arizona and northern Mexico (Bruhn, 1971:323).

Schizophrenia is thought to be a disease of dopamine hyperactivity; victims of Parkinson's disease, on the other hand, suffer from dopamine insufficiency, which is partially offset nowadays by the administration of a new drug, L-dopa, often in combination with Tofranil or some other amphetamine. The adenyl cyclase experiments enabled the UCLA team to show that dopamine receptors are present in the higher regions of the brain, which are concerned with the more complex experiences and thus are more likely to be the seat of alternate states of consciousness, or "hallucinations." Their work, report the UCLA investigators, makes it appear that the psychotic mimicking effects of LSD, first noted by Hofmann more than thirty years ago, may also be related to hyperactivity of brain dopamine systems. These insights have obvious implications for work on new drugs for schizophrenia on the one hand and Parkinson's disease on the other; recognition of their biochemical kinship was, of course, still far off in the distant future when Hofmann correctly predicted the ultimate benefits of LSD for brain research. Nor did he suspect at the time that "primitive" psychotherapy had been making effective use of a natural compound very like LSD for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years.

Lysergic acid, Hofmann (1967) has explained,

. . . is the foundation stone of the ergot alkaloids, the active principle of the fungus product ergot. Botanically speaking ergot is the sclerotia of the filamentous fungus Claviceps purpurea which grows on grasses, especially rye. The ears of rye that have been attacked by the fungus develop into long, dark pegs to form ergot. The chemical and pharmacological investigation of the ergot alkaloids has been a main field of research of the natural products division of the Sandoz laboratories since the discovery of ergotamine by A. Stoll in 1918. A variety of useful pharmaceuticals have resulted from these investigations, which have been conducted over a number of decades. They find wide application in obstetrics, in internal medicine, in neurology and psychiatry. (p. 349)

Historic Breakthrough: The Discovery of LSD

The significant part of our story begins in 1938, when Hofmann and an associate, Dr. W. A. Kroll, discovered d-lysergic acid diethylamide, a derivative of ergot. Because it was the twenty-fifth compound in the lysergic acid series to be synthethized at Sandoz, it was named LSD-25, the designation under which it was to become famous; but at the time, since tests on animals showed nothing of pharmaceutical interest, it was laid aside without being tested on humans, Five years later, on April 16, 1943, in the course of working with two other ergot derivatives, Hofmann suddenly experienced feelings of restlessness and dizziness, so much so that he was compelled to go home. Later that afternoon, as he subsequently wrote in his notebook, while lying down in a semiconscious and slightly delirious state he suddenly experienced "fantastic visions of extraordinary realness, and with an intense kaleidoscopic play of colors," a condition that endured about two hours, and in the course of which self-perception and the sense of time itself were changed.

At that time LSD was not actually suspected as the cause, but as it happened, he had that same morning recrystallized d-lysergic diethylamide tartrate while working with two other ergot derivatives. Their effects were well known, however, and because he suspected that he might have accidentally ingested some of the LSD compound, he decided to test the chemical under more controlled conditions. The following week he administered to himself what he then took to be a very small dose of one-quarter of one milligram (actually, as he discovered and as we now know, a very substantial amount) and soon found himself in for a six-hour-long and often highly dramatic "trip." Thus began the saga of LSD-25, the most potent psychoactive or "psychedelic" compound known up to that time, whose discovery ushered in a whole new era of exploration into the nature of the unconscious and the historical role of hallucinogens in the evolution and maintenance of metaphysical and even social systems. And inasmuch as it opened new vistas for the cross-cultural and multidisciplinary investigation of what has been called "inner space," one cannot but agree with psychologist Duncan B. Blewett (1969) that the discovery of LSD marked, together the splitting of the atom and the discovery of the biochemical role of DNA, the basic genetic material of inheritance, one of the three major scientific breakthroughs of the twentieth century.*

Ololiuhqui, Sacred Hallucinogen of the Aztecs

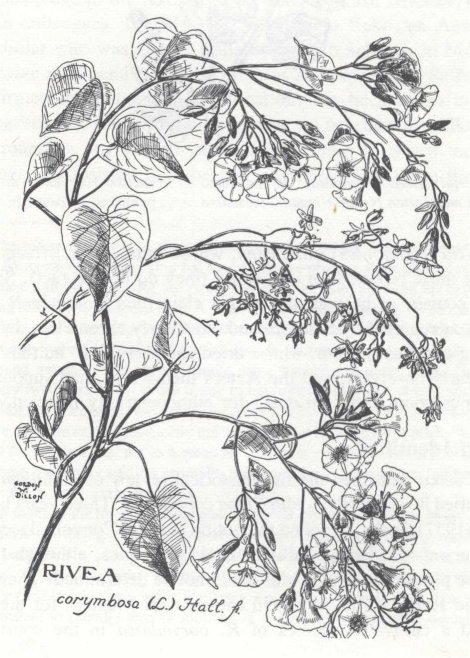

Among the several sacred hallucinogens that were apparently too vital to the individual and social equilibrium of Indian Mexico to be suppressed after the Conquest, and that took on the trappings of Christian iconography without losing their essential pre-Christian meanings, was ololiuhqui. Ololiuhqui (ololuc), an Aztec word meaning "round thing," contains no clue to its botanical identity, any more than does teonandcatl, food or flesh of the gods, the name by which the Aztecs called certain hallucinogenic mushrooms. Although Ruiz de Alarcon (1629) declined to identify the source of ololiuhqui, there should have been no doubt from the first that the term referred to the lentil-shaped light-brown seeds of the morning glory, for Hernandez had accurately pictured the plant in his sixteenth-century study and Mexican botanists had long identified it as Rivea corymbosa.

Nevertheless, prior to 1941, when Schultes published a definitive review of the sacred morning glories and once and for all identified ololuc or ololiuhqui as R. corymbosa, its identity was subject to controversy, primarily because a noted American botanist, William A. Safford, had no faith in the botanical knowledge of the Aztecs, of the early Spanish scholars, or even of his Mexican colleagues. In 1919, Dr. Blas Pablo Reko, an Austrian-born Mexican scholar who was later to collaborate with Schultes in Mexico, had collected ololuc seeds and identified them as R. corymbosa. Safford (1915, 1920) confirmed the botanical determination, but because no intoxication followed ingestion of the seeds, and because no psychoactive alkaloids had ever been found in any Convolvulaceae, the order to which the morning glories belong, he insisted that the real ololiuhqui had to be the seeds of

Datura inoxia (meteloides) (toloatzin), whose intoxicating effects were said to resemble those reported for ololiuhqui (they do not, in fact). Safford was wrong, of course, as he was also in his claim that teonanácatl was not a mushroom, as reported by Sahagün and other early chroniclers, but probably was nothing else than peyote, whose dried and shriveled "buttons" Sahagün and other early observers, and the Aztecs themselves, had supposedly mistaken for mushroom caps! So much for ethnocentricity in science.

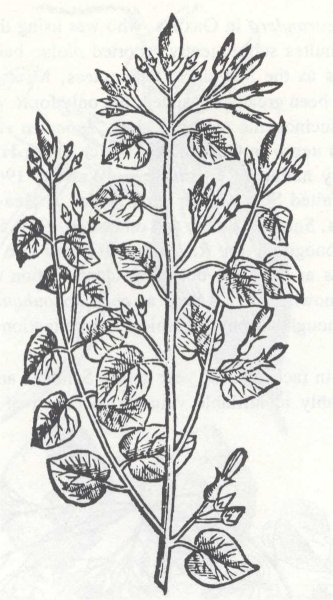

Ololiuhqui (Rivea corymbosa). As illustrated by Francisco Hernandez in his Rerum medicarum Novae Hispania thesaurus . . ., published in Rome in 1651.

Ololiuhqui Identified

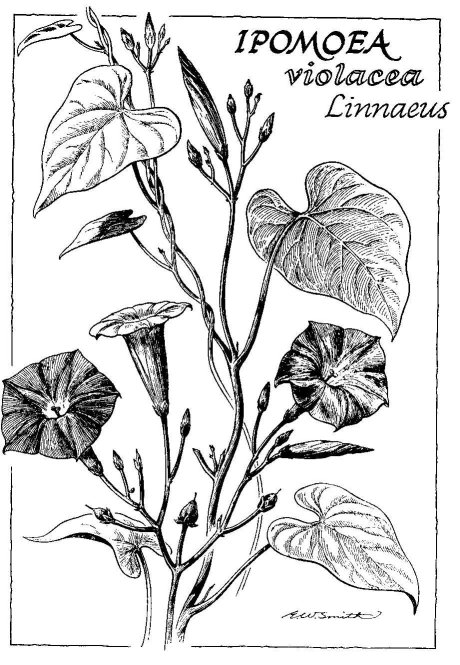

In 1934 Reko published the first historical review of ololiuhqui use, and again identified it—correctly—with Rivea corymbosa. Three years later, C. G. Santesson (1937) finally dispelled the notion that the Convolvulaceae, specifically R. corymbosa, lacked hallucinogenic principles, although the precise nature of the psychoactive alkaloids could not be determined. Then, in 1939, Schultes and Reko, while on a field trip through Mexico, for the first time encountered a cultivated species of R. corymbosa in the courtyard of a Zapotec Indian curandero in Oaxaca, who was using the seeds in divinatory curing rites. Schultes subsequently reported ololuc being used among such Oaxacan Indians as the Mazatecs, Chinantecs, Mixtecs, and others; since then, the list has been greatly expanded, not only for R. corymbosa but for the other major hallucinogenic morning glory, Ipomoea violacea, whose seeds are called badoh negro in Oaxaca, and which in pre-Hispanic times was the sacred divinatory hallucinogen tlitliltzin (Wasson, 1967a). This species is known in the United States under such names as Heavenly Blue, Wedding Bells, Blue Stars, Summer Skies, and others. In 1941, Schultes published his now classic monograph on R. corymbosa and the divine hallucinogen ololiuhqui. Thus at least the botanical identification of ololiuhqui and its mother plant, known to the Aztecs as coatl-xoxouhqui, green snake plant, was settled, although its phytochemical determination had to wait another twenty years.

Meanwhile—in fact, just the year before Schultes and Reko collected the first unquestionably identifiable voucher specimen of Rivea corymbosa in Oaxaca—LSD had been discovered and synthethized in Switzerland. It was this event and subsequent research at Sandoz into psychotomimetic alkaloids that caused the French mycologist Roger Heim to send samples of teonanricatl mushrooms to Hofmann, "on the assumption that the necessary conditions for a successful chemical investigation would be present in the laboratory in which LSD was discovered" (Hofmann, 1967:350). They were; Hofmann discovered psilocybine and psilocine as the active principles of the most important hallucinogenic fungi. Close collaboration followed with Heim and with the American ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson, and this in turn led directly to the startling discovery of the active principles of R. corymbosa and I. violacea.

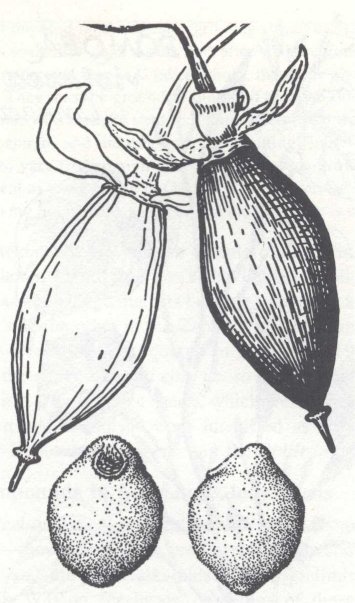

Rivea corymbosa. Capsules and seeds.

In the interim, there were to be two more research reports on the effects of morning-glory seeds. Santesson had been certain that alkaloids were present but was not able to identify them. In 1955, the Canadian psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond, who had long been interested in the use and effects of peyote, especially in the context of the Native American Church among Canadian Indians, experimented on himself with ololiuhqui seeds. His experience did not duplicate that reported historically from Mexico, but after taking 60 to 100 seeds he passed into what he described as a state of listlessness, accompanied by increased visual sensitivity and followed by a prolonged period of relaxed well-being. In 1958, V. J. Kinross-Wright published the entirely negative results of ololiuhqui experiments with eight male volunteers, of whom not a single one reported any effect whatever, even though individual doses ranged up to 125 morning-glory seeds!

But this hardly squared with the accounts of the early chroniclers, nor with the modern observations of Schultes and others. Quite apart from set and setting, which, as we know, are crucial variables in the use of any hallucinogen, the problem evidently lay in the manner of preparation of the seeds. To quote Wasson (1967a):

In recent years a number of experimenters have taken the seeds with no effects and this has led one of them to suggest that the reputation of ololiuhqui is wholly due to autosuggestion. These negative results may be explained by inadequate preparation.

The Indians grind the seed on the metate (grinding stone) until it is reduced to flour. Then the flour is soaked in cold water, and after a short time the liquor is passed through a cloth strainer and drunk. If taken whole, the seeds give no result, or even if they are cracked. They must be ground to flour and then the flour is soaked briefly in water. Perhaps those who took the seeds without results did not grind them, or did not grind them fine enough, and did not soak the resulting flour. The chemistry of the seeds seems not to vary from region to region, and seeds grown in the Antilles and Europe are as potent as those grown in Oaxaca. I have taken the black seeds (Ipomoea violacea) twice in my home in New York, and their potency is undeniable. (p. 343)

In 1959, Wasson sent Hofmann a sample of seeds in two small bottles. With it came a letter, identifying one as having been collected in Huautla de Jimenez, the Mazatec village that has become famous as a center of the living mushroom cult, and the other in the Zapotec town of San Bartolo Yautepec. The first batch, wrote Wasson (quoted in Hofmann, 1967), he took to be ololiuhqui, i.e. the seeds of Rivea corymbosa. Upon botanical investigation, this proved correct. The Zapotec seeds, which were black and angular rather than light-brown and roundish, were identified as Ipomoea violacea, the badoh negro of Zapotec curanderos and the ditazin of the Aztecs.

LSD-like Compounds in Morning-Glory Seeds

Initial chemical-analytical studies with Wasson's small samples proved exciting enough—they indicated the presence of indole compounds structurally related to LSD and the ergot alkaloids. These preliminary results caused Hofmann to ask Wasson for larger quantities of these interesting seeds. Wasson enlisted the aid of the veteran Mexican ethnologist Roberto Weitlaner, like B. P. Reko of Austrian birth, an untiring field ethnologist even when he was well into his seventies, and his daughter Irmgard Weitlaner Johnson, herself a noted specialist in pre-Columbian and contemporary Indian textiles. With the assistance of the Weitlaners, father and daughter, Wasson was able to send Hofmann 12 kilograms of Rivea corymbosa seeds and 14 kilograms of the seeds of the blue-flowered Ipomoea violacea.

With these considerable quantities, which reached Hofmann in the early part of 1960, he was able to isolate their main active principles and identify them as ergot alkaloids-d-lysergic acid amide (ergine) and d-isolysergic acid amide (isoergine). These are closely related to d-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD):

From the phytochemical point of view this finding was unexpected and of particular interest because lysergic acid alkaloids, which had hitherto only been found in the lower fungi of the genus Claviceps , were now for the first time found to be present in higher plants, in the plant family Convolvulaceae.

The isolation of lysergic acid amides from ololiuhqui thus caused a research series to close like a magical ring.

It was the discovery of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) as a highly active psychotomimetic agent, during investigations on simple acid amides, that our research in the field of hallucinogenic compounds commenced. It was within the framework of this activity that the Mexican magic fungi came to our laboratories. It was during the course of these investigations that the personal contact was made between the writer and R. G. Wasson and it was as a result of this contact that the investigations of ololiuhqui were conducted. In this magic drug, lysergic acid amides, which made their appearance in the initial stages of our psychotomimetic research, were again found as active principles. (Hofmann, 1967:351-352)

Schultes (1970) notes that the nomenclature and taxonomy of the Convolvulaceae are still in a state of confusion. Rivea, mainly an Asiatic genus of woody vines, has five Old World but only one New World species, R. corymbosa, which occurs, in addition to Mexico and Central America, in the southernmost United States, parts of the Caribbean, and on the north coast of South America. R. corymbosa is known in the literature by at least nine synonyms, the two most common being Ipomoea sidaefolia and Turbina corymbosa. Ipomoea, a genus of climbing herbs and shrubs, comprises at least 500 species in warm and tropical parts of the hemisphere. I. violacea ("Heavenly Blue," etc.), is also often called!. tricolor or I. rubro-caerulea. The psychotropic principles of R. corymbosa and I. violacea are shared by other morning-glory species, but the degree to which any of these were or still are used by Indians is not known. However, the fact that some are called by popular names that allude to intoxicating properties (e.g. arbol loco, crazy tree, or borrachera, drunkenness, a term that is also applied to Datura), suggests that these are at least known, if not actually utilized.

Presumably to head off their popularization as an inexpensive natural psychedelic in the United States commercial seeds of Heavenly Blue and other varieties were ordered coated with a noxious substance. Since the artificial coating is not inheritable, nothing, of course, would prevent hallucinogenic use of subsequent generations of seeds.

Nonetheless, for whatever reason, and despite the fact that the natural chemistry of morning-glory seeds is far more reliable than that of synthetic hallucinogens available on the black market, except on the West Coast* they seem not to have become integrated to any notable extent into the drug subculture. Nor do we have any indication that morning glories ever entered ritual contexts in the Old World or even in South America. Thus the discovery and utilization of their psychic effects apparently belongs exclusively to the Indians of Mexico.

Ololiuhqui in Indian Religion

According to Dr. Francisco Hernandez, that learned and observant physician to the Spanish crown who studied the medicinal lore of Indian Mexico in the sixteenth century and whose great work on the plants, animals, and minerals of New Spain was published in Rome in 1651,

• . when the priests wanted to communicate with their gods, and to receive messages from them, they ate this plant (ololiuhqui) to induce a delirium. A thousand visions and satanic hallucinations appeared to them.

Morning-Glory Seeds as Divinity

Actually, as the Spaniards quickly saw, ololiuhqui, like the mushrooms and other magical plants, was more than just a means of communication with the supernatural. It was itself a divinity and the object of worship, reverently preserved within the secret household shrines of village shamans, curers, and even ordinary people in the early Colonial era. Carefully hidden in consecrated baskets and other dedicatory receptacles, the seeds were personally addressed with prayers, petitions, and incantations, and honored with sacrificial offerings, incense, and flowers. Ololiuhqui was apparently considered to be male. It could even manifest itself in human form to those that drank the sacred infusion. Accounts of the worship of the seeds and other sacred plant hallucinogens as divinities are too specific and they occur too often in the Colonial literature to be dismissed out of hand as mere ethnocentric misconstructions of indigenous belief. In fact, if one looks at peyote among the Huichols, or the mushrooms in central Mexico and Oaxaca, one finds the same sort of identification with the divinities: peyote is the divine deer or supernatural master of the deer species, addressed as Elder Brother and merging with some of the leading deities, and the sacred mushrooms are personified and addressed as "ancestors," "ancient ones," "little princes of the waters," "little saints," and the like.

As mentioned, the best early source on ololiuhqui, as on seventeenth-century indigenous beliefs and practices in general, is Ruiz de Alarcón's Tratado on the "idolatries and superstitions" of the Indians of Morelos and Guerrero. Several chapters of this important work are devoted to what their author calls "the superstition of the ololiuhqui," to which, he complains repeatedly, the Indians continued to attribute divinity in the face of the severest denunciations and punishment. Worse, he writes, the same "superstition" threatened to spread to the lower strata of Colonial society, for which reasons he said he felt compelled to refrain from identifying the plant botanically, except to say that it was a vine growing profusely along the banks of rivers and streams in his native Guerrero and neighboring Morelos (as it still does).

The Indians had special incantations that they addressed to the divine ololiuhqui to cause him to appear and assist in divination and the curing of illnesses:

"Come hither, cold spirit, for you must remove this heat (fever), and you must console your servant, who will serve you perhaps one, perhaps two days, and who will sweep clean the place where you are worshiped." This conjuration in its entirety is so accepted by the Indians that almost all of them hold that the oloiiuhqui is a divine thing, in consequence of which . . . this conjuration accounts for the custom of veneration of it by the Indians, which is to have it on their altars and in the best containers or baskets that they have, and there to offer it incense and bouquets of flowers, to sweep and water the house very carefully, and for this reason the conjuration says: " . . who will sweep (for) you or serve you one or two days more." And with the same veneration they drink the said seed, shutting themselves in those places like one who was in the sanctasanctórum, with many other superstitions. And the veneration with which these barbarous people revere the seed is so excessive that part of their devotions include washing and sweeping (even) those places where the bushes are found which produce them, which are some heavy vines, even though they are in the wildernesses and thickets. (Ruiz de Alarcon, 1629)

Thwarting the Clergy

The Indians, he complains, seemed always to find new ways to thwart even the best efforts of the clergy, including himself as the investigating emissary of the Holy Office, hiding their supplies of ololiuhqui in secret places, not only because they were afraid of discovery and punishment by the Inquisition, but for fear that ololiuhqui itself might punish them for having suffered it to be desecrated by the touch of alien hands. Always, he reports, the Indians seemed to be more concerned with the good will of ololiuhqui than the displeasure and penalties of the clergy. Moreover, they often pretended to cooperate in the denunciation of "idolatry" only so as to better conceal its practice. The following story of such a denunciation, involving a woman who had some ololiuhqui in her possession and several of her relatives, will serve as an illustration.

It seems that the woman had been involved in a domestic quarrel and one of her male relatives had admitted to Ruiz de Alarcón that she owned a basket filled with the sacred seeds. Ruiz de Alarcón wanted to check the house immediately, but his informant asked if he might be allowed to do it alone, for he knew her hiding places and would be able to determine quickly if the ololiuhqui and all the other things he had denounced were still in the house. Ruiz de Alarcón agreed and let the relative do the searching alone; the man soon returned to report that the basket was nowhere to be found. Ruiz de Alarcón had the woman and her sister placed under arrest and after questioning them "with all diligence" for an entire day, they finally admitted that at the first sign of danger they had quickly removed all the ololiuhqui from the oratory and divided it into many small segments, each to be carefully secreted in a different place:

When she was asked why she had denied it so perversely she answered, as they always do, "Oninomauhtiaya," which means, out of fear I did not dare. It is important to indicate that this is not the same fear which they have for the ministers of justice for the punishment they deserve, rather (it is) the fear that they have for this same ololiuhqui, or the deity they believe resides in it, and in this respect they have their reverence so confused that it is necessary to have the help of God to remove it; so that the fear and terror that impedes their confession is not one which will annoy that false deity that they think they have in the ololiuhqui, so as not to fall under his ire and indignation. And thus they say (to it), "Aconechtlahuelis," "may I not arouse your ire or anger against me."

This particular round of investigations completed, the good friar returned to Atenango, seat of his benefice in what is now the state of Guerrero. Here,

. . knowing the blindness of these unfortunate souls, to remove from them such a heavy burden and such a strong impediment to their salvation,

he began to preach at once against ololiuhqui, ordering the vines that grew along the river to be cleared away, and casting quantities of the confiscated seed into the fire in the presence of its owners. With this, he writes, "Our Lord was served." The Indians, predictably, didn't see it that way at all, and when he soon fell seriously ill, they promptly credited the ailment to the displeasure of ololiuhqui,

. . . for not having revered it, it being earlier angered by what I had done to it: this is how blind these people are.

He recovered and to prove the Indians wrong, he chose a solemn feast day to assemble the entire beneficio for another, more impressive burning of olohuhqui. He ordered an enormous bonfire built, and into it,

. . . with all of them watching, I had almost the totality of the said seed which I had collected burned, and I ordered burned and cleared again the kind of bushes where they are found.

Alas, the old ways persisted:

Such is the diligence of the devil that it works against us, for by his cunning we find each day new damage in this work, and thus it is good if the ministers of each jurisdiction are diligent in investigating, extirpating and punishing these consequences of the old idolatry and cult of the devil. . . .

As Wasson (1967a) notes, throughout these references of early Colonial times

. . . there runs a note of sombre poignancy as we see two cultures in a duel to the death—on the one hand, the fanaticism of sincere Churchmen, hotly pursuing with the support of the harsh secular arm what they considered a superstition and an idolatry, and, on the other, the tenacity and wiles of the Indians defending their cherished ololiuhqui. The Indians seem to have won out. Today in almost all the villages of Oaxaca one finds the seeds still serving the natives as ever present help in time of trouble. (pp. 339-340)

Morning Glory and Christian Acculturation

The subtle manner in which the sacred morning-glory seeds have become interwoven with Christian elements is evident in a step-by-step description, paraphrased by Wasson (1967a) from an account dictated by a Zapotec Indian curandera, Paula Jimenez of San Bárt°lo Yautepec:

First, a person who is to take the seeds must solemnly commit himself to take them, and to go out and cut the branches with the seed. There must also be a vow to the Virgen in favor of the sick person, so that the seed will take effect with him. If there is no such vow, there will be no effect. The sick person must seek out a child of 7 or 8 years, a little girl if the patient is a man, a little boy if the patient is a woman. The child should be freshly bathed and in clean clothes, all fresh and clean. The seed is then measured out, the amount that fills the cup of the hand, or about a thimble full. The time should be Friday, but at night, about 8 or 9 o'clock, and there must be no noise, no noise at all. As for grinding the seed, in the beginning you say, "In the name of God and of the Virgencira ("dear little virgin"), be gracious and grant the remedy, and tell us, Virgencira, what is wrong with the patient. Our hopes are in thee." To strain the ground seed, you should use a clean cloth—a new cloth, if possible. When giving the drink to the patient, you must say three Pater Nosters and three Ave Marias. A child must carry the bowl in his hands, along with a censer. After having drunk the liquor, the patient lies down. The bowl with the censer is placed underneath, at the head of the bed. The child must remain with the other person, waiting, to take care of the patient and to hear what he will say. If there is improvement, then the patient does not get up; he remains in bed. If there is no improvement, the patient gets up and lies down again in front of the altar. He stays there a while, and then rises and goes to bed again, and he should not talk until the next day. And so everything is revealed. You are told whether the trouble is an act of malice of whether it is an illness. (pp. 345-346)

Morning Glory and Mother Goddess

In Spanish the seeds of the morning glory are commonly known as semilla de la Virgen, seed of the Virgin. The extraordinary importance of the doncella, niiia or young maiden, in the preparation of the morning-glory infusion as well as the sacred mushrooms and other divinatory agents has been noted by Wasson (1967a), who thought the Indians might have seized on Christian iconography in this connection because it was already familiar to them in their own supernatural system. I think he was quite right: these associations may well have deep roots in the psychedelic complex of pre-Hispanic Mexico.

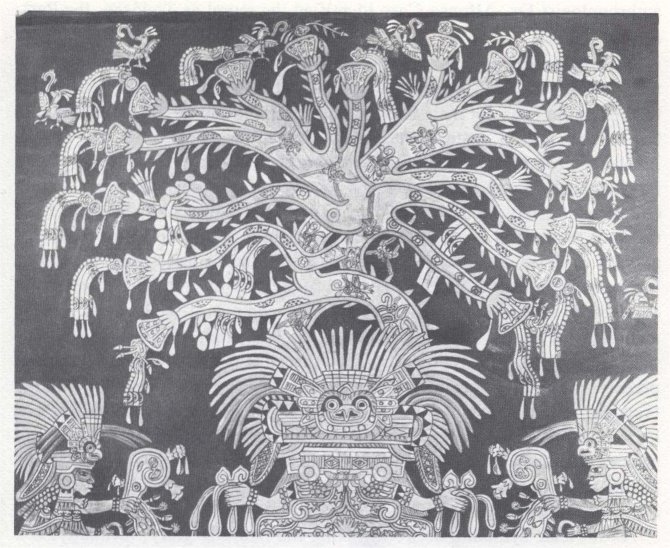

Ololiuhqui in art. Once thought to represent the male rain god TIaloc, this spectacular mural from Teotihuácan, Mexico, dated ca. A.D. 500, actually depicts a great Mother Goddess and her priestly attendants with a highly stylized and elaborated morning glory, Rivea corymbosa , the sacred hallucinogenic ololiuhqui of the Aztecs.

In 1940, long before the identification of plants in pre-Columbian art assumed its present significance in relation to hallucinogenic research, archaeologists uncovered a complex of mural paintings at Tepantitla, a compound of sacred buildings within the great pre-Hispanic city of Teotihuácan, which flourished from the first to the eighth century A.D. north of the present Mexico City. These paintings have been dated to the fifth or sixth century A.D., when Teotihuácan was not only the greatest urban center in the New World but one of the largest cities anywhere, with perhaps as many as 100,000-200,000 inhabitants.

The most prominent elements in the mural are a deity from which flows a stream of water that covers the earth and feeds its vegetation, and above the central figure a great vine-like plant with white funnel-shaped flowers at the ends of its many convoluted branches. Seeds fall from the deity's hands and two priest-attendants flank the main figure on either side. Below this scene are many small human figures playing, singing, dancing, and swimming in a great lake. Because the painting appeared to conform to a well-known Aztec tradition of a paradise ruled over by the male rain god Tialoc, and because the deity itself seemed to have some of Tialoc's attributes, the late Mexican anthropologist Dr. Alfonso Caso identified the mural as Tlalócan, the Paradise of Tlaloc.

That identification has recently undergone major revisions. Several specialists in the art and iconography of ancient Mexico have come to recognize the central deity as not male but female, which eliminates the male TIaloc of the Aztec pantheon. Instead, the deity of Tepantitla appears now to be an All-Mother or Mother Goddess, perhaps akin to the great Aztec fertility deity Xochiquetzal, Precious Flower, or another of her manifestations, Chalchiutlicue, Skirt of Jade, the Mother of Terrestrial Water. With the reinterpretation of the central deity has come a redefinition of the flowering plant that appears to tower tree-like above her. With Schultes's assistance, the "tree" has been identified by myself as none other than the morning glory Rivea corymbosa, clearly recognizable to the practiced eye of the botanist, despite an overlay of mythological elements and the adaptation of natural characteristics to the stylistic conventions of Teotihuácan (Furst, 1974a). Here then we perceive a direct association in an ancient work of art between a Mother Goddess, water, vegetation, and the divine morning glory, a plant that is well known to prefer the banks of streams as its natural habitat and that is still considered to be a messenger of the rainy season, because that is when it first begins to bloom—quite apart from its inherent magical powers of clairvoyance and transformation.

An intricate symbolic network linking the morning glory, fecundity, and the Virgin Mary, not only as the inheritor of the qualities of the pre-Hispanic Mother Goddess but specifically as the divine Mother of life-giving water, was first recognized by Dr. Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán, a well-known applied anthropologist as well as medical doctor who at this writing is Undersecretary of Education for Cultural and Indian Affairs in the national government of Mexico.

According to some early Colonial sources, he wrote in Medicina y Magia (1963), a significant work dealing largely with the effects of acculturation on the religion, medicine, and magic of pre-Hispanic Mexico, the Indians of seventeenth-century New Spain thought of the male oioliuhqui as brother to a sacred but botanically unidentified plant called Mother of Water. Intimately related to the male morning glory, this female plant symbolizing a water goddess might have come to be syncretized as the result of Christian acculturation with the qualities of the Virgin Mary, who thereby assumed a Christopagan identity as "Mother of Water" or "Mistress of the Waters"—names by which she is actually still called in some villages of central Mexico.

One cannot help wondering to what degree these post-Hispanic folk traditions might actually reflect much older beliefs—such as those that more than a millenium earlier inspired the unknown master of the Tepantitla murals to link the Mother Goddess of Terrestrial Water and Fecundity with the sacred divinatory morning glory Rivea corymbosa.

God of Flowers and "Flowery Dream"

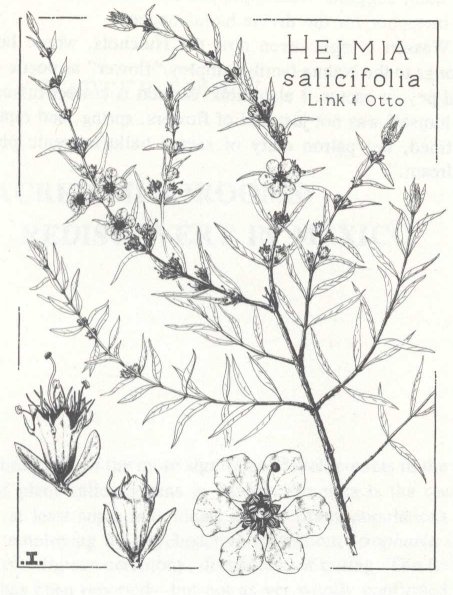

Recently, Wasson (1973), with the expert assistance of Schultes, has again contributed in a major way to our understanding of central Mexican symbolism with an analysis of the floral decorations on a famous stone sculpture of the Aztec God of Flowers, Xochipilli, in the Museo Nacional de Antropologia in Mexico City, In addition to what he believes to be stylized depictions of the hallucinogenic mushroom Psilocybe aztecorum, he and Schultes identified flowers carved on the god's left leg as near-naturalistic representations of R. corymbosa . There is no doubt in my mind that he is correct. Still other flowers depicted on this magnificent fifteenth-century idol were recognized as those of Heimia salicifolia, the sacred auditory hallucinogen sinucuichi of the Nahua-speaking Indians of central Mexico, and of Nicotiana tabacum, one of the two principal sacred tobacco species (the other, as we recall, is Nicotiana rustica, picitl).

The generic Aztec term for flower was xochitl. In Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, writes Wasson (1973: 324), the hallucinogenic experience was called temixoch, the "flowery dream," and the sacred mushroom, teonaniicatl (teo = divine, god; neicatl = food or flesh), was also known as xochinanácatl.

"Flower," then, suggests Wasson, appears to have been used by the Aztec poets as a metaphor for the divine hallucinogens

I think Wasson is right: even now the Huichols, whose language, like Aztec, belongs to the Nahua family, employ "flower" as poetic metaphor for their sacred peyote cactus. I also think Wasson is correct in suggesting that Xochipilli himself was not just god of flowers, spring, and rapture, as he is usually defined, but patron deity of sacred hallucinogenic plants and the "flowery dream."

*As this book was nearing completion, the nation's newspapers were filled with disclosures of large-scale secret experimentation with LSD by the Pentagon and the Central Intelligence Agency on many hundreds (more than 1500 in the Army's tests alone) of human subjects, of whom at least some were not informed beforehand what drug they were being given—a method that has been characterized as unethical by, among others, such medical authorities as Dr. Judd Marmor, President of the American Psychiatric Association. The secret tests, whose results were not accessible to the general scientific community, continued for at least a dozen years into the late nineteen sixties—in other words, long after LSD was made illegal, extensive campaigns were mounted on the national and local level to convince the public of its dangers, and its unauthorized manufacture, possession, sale, use or even free distribution made subject to lengthy prison terms. The New York Times of August 1, 1975, quoted Dr. Albert Hofmann to the effect that he was repeatedly approached during the late nineteen-fifties by United States Army researchers looking for a way to mass-produce large quantities of the drug; he had never been told the reason for the Army's interest, he said, but from the extremely large quantities being discussed assumed that it was for weapons research. Whereas a standard experimental dose was in the range of 250 to 300 micrograms, he said, the Army was interested in finding a process that could produce "many kilos" (a microgram is one millionth of a gram, a kilo one thousand grams). "The Army people came back many times," Dr. Hofmann told reporters, "every two years or so, to see if any technological progress had been made," adding that the visits stopped after other researchers succeeded in developing such a process in the early nineteen-sixties. He also said he personally did not like what the Army was after, "because! had perfected LSD for medical use, not as a weapon. . . . In any case, the research should be done by medical people and not by soldiers or intelligence agencies," especially in light of the serious risks posed by the potent psychochemical.

It must seem to many the height of irony and of official cynicism that even as civilian medical research with LSD was being severely hampered by legal restrictions, and thousands of Americans, mostly young people, were being jailed and marked for life with felony records on LSD-related charges, the drug was being covertly administered to other thousands to see if it might prove useful for chemical warfare, while the Army was seeking ways to have it manufactured in quantities equivalent to literally tens of millions of individual experimental doses!

*The seeds of the so-called "Hawaiian wood roses" (Argyreia spp.)—actually not roses at all but with the morning glories members of the Convolvulaceae,--achieved some popularity for easily accessible "highs," which, however, turned out to have extremely unpleasant after-effects, such as nausea, constipation, vertigo, blurred vision, and physical inertia (Emboden, 1972b:26). Their complex chemistry includes amides of lysergic acids.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|