CHAPTER SEVEN THE SACRED MUSHROOMS: REDISCOVERY IN MEXICO

| Books - Hallucinogens and Culture |

Drug Abuse

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE SACRED MUSHROOMS: REDISCOVERY IN MEXICO

If true, surely one of the more significant developments in the study of the ritual use of plant hallucinogens in Middle America is the recent spate of reports that at least some individuals in two Maya populations in southern Mexico are employing the psychoactive mushroom Stropharia cubensis* in the context of religious ceremony, divination, or curing. The two groups for which this has been reported—but not as yet wholly confirmed by scientifically trained observers—are the Chol, who live not far from the Classic Maya ceremonial and funerary center of Palenque, Chiapas (which, like other Maya lowland sites is thought to have been built and inhabited by ChoIanspeaking Maya), and one small population of Lacandones, of whom only a few remnant groups survive today in the general area of the Usumacinta River near the border of Guatemala. Pending the necessary confirmation, the several accounts that have reached anthropologists and others in the recent past have already led to speculation that perhaps some other Maya-speaking populations may also be found to have retained—or else re-adopted—mushroom rituals that were long thought to have died out among them centuries ago.

Considering the stream of non-Indian mushroom "devotees" that descended on the Mazatec Indians of Oaxaca after their mushroom rites were publicized in the 1950's and early 1960's, perhaps all that should be said for now about the Maya situation is that some reputable scholars have become convinced over the past several years that mushrooms are being employed ritually by at least some Chol and Lacandón Maya. It is true, however, that colleagues who sought to confirm this on the spot were unable to do so in the brief time available to them. At the very least, it seems, the local informants are more reticent on the subject now than even a few years ago. Whatever the reason, the most recent efforts to obtain first-hand information have proved unavailing. The problem is further complicated by a peculiarity of S. cubensis: it is a dung fungus that nowadays grows typically on the dung of cattle (as it does, for example, in the grassy meadows all around Palenque). This might lead one to think that it could not be a native New World species but must have been introduced together with cattle after the conquest. Against this, however, we have the fact S. cubensis has not been reported in Spain or southern Europe, and, in any event, as we shall see in another chapter, there is a native ruminant whose droppings are perfectly capable of playing host to S. cubensis and that played an extraordinarily prominent role in the cosmology of the Maya and other Indian peoples. That animal is the deer.

The use of an hallucinogenic mushroom in Chol country was first reported by a student of M. D. Coe at Yale University (Furst, 1972a:x); the existence of what appeared to be a well-integrated complex of mushroom intoxication, for the purpose of conversing with the deities, was first published by a specialist in Classic Maya art, Merle Greene Robertson (1972), in a paper on the carved monuments of Yaxchilân, an important Maya site on the Usumacinta River. In the course of her research, Mrs. Robertson said, she learned that some Lacandón priests consumed the mushrooms in ritual seclusion, sometimes within the ruins of the smaller temple or funerary structures at Yaxchilin. The mushrooms, she was told, are prepared in specially consecrated pottery bowls that are used for no other purpose and that differ from the so-called "god pots" with anthropomorphic decorations in which incense is burned.

The Lacandones have been subjected to anthropological inquiry for many decades, and it must be emphasized that although ritual intoxication is an essential aspect of their ceremonial life, not one of these investigators witnessed, or heard of, such mushroom rites. Nonetheless, Mrs. Robertson was told by her informants that the sacred mushrooms had served as a medium of communication with the gods for "as long as the oldest" member of that particular group could remember. One cannot help but feel that such information must be taken seriously; the Indians learned long ago—with good and sufficient reason—to conceal and disguise whatever they thought might provoke the wrath or disapproval of the ecclesiastical authorities and other outsiders. Besides, with the exception of peyote, the plant hallucinogens have only recently become the focus of anthropological inquiry in the Americas and elsewhere; field workers are only just beginning to learn to ask the right questions (or better, not to ask questions at all but wait patiently for the information to come naturally, which may, and often does, take many weeks or months of living with the people and convincing them that one means no harm nor desires to change their ways). So it should perhaps not surprise us that neither A. M. Tozzer (1907), author of a classic comparative study of the Lacandones, nor other students of Maya culture considered that ritual intoxication—which has been well-described—might have involved more than just alcohol.

However much it remains to be substantiated, the reported present-day existence of mushroom use among certain Maya groups should go a long way toward settling the question of mushroom "cults" among the ancient Maya, and the reasons for its apparent disappearance from the one area of Middle America where the archaeological evidence for such a cult has been most persuasive.

As Thompson (1970) noted, the Colonial sources on the Maya, which include several useful works on herbal medicines, are silent about intoxicating mushrooms, as well as about other botanically identified psychoactive plants (with the exception of tobacco), however much the sacred mushrooms and plant hallucinogens in general fascinated their contemporaries writing in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century central Mexico. Yet it has long been known that as long as 3000 years ago at least the inhabitants of the highlands and the Pacific slope of Guatemala, as well as some of their neighbors, held certain mushrooms to be so sacred and powerful—perhaps even divine—that they represented them in great number in sculptured stone. In fact, the production of mushroom images or idols of varying symbolic complexity endured in Mesoamerica for nearly two millennia, from ca. 1000 B.C. to the end of the Classic period, ca. A.D. 900, suggesting that a cult of sacred mushrooms not only lasted thousands of years but was anciently more widespread than the sixteenth-century chronicles would lead us to believe.

"Mushroom of the Underworld"

Actually, Thompson was only partly right when he said that the Spaniards were silent on the matter of hallucinogens among the Maya, for several of the early dictionaries compiled by Spanish priests in the Guatemalan highlands demonstrate considerable Indian knowledge of the intoxicating effects of a number of mushroom species.* One of the oldest of the Colonial word lists, the Vico dictionary, which was apparently compiled well before the 1550's, explicitly mentions a mushroom called xibalbaj okox (xibalba = underworld, or hell, realm of the dead; okox = mushroom), with the implication that this species is hallucinogenic. In fact, in this context xibalbaj refers not just to the Maya underworld, with its nine lords and nine levels, but also to having visions thereof, so that the name can be understood to mean "mushroom which gives one visions of hell" or "of the world of the dead." The same intoxicating mushroom is also mentioned in a later word list, Fray Tomas Coto's Vocabulario de la lengua Cakchiquel, dated ca. 1690 (manuscript in the library of the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia), which pulls together much of the earlier material on Cakchiquel-Maya. According to the Coto dictionary, xibalbaj okox, mushroom of the underworld, was also called k'aizalah okox, which can be translated as "mushroom that makes one lose one's judgment."

The Coto dictionary also describes a mushroom called k'ekc'un, which inebriates or makes drunk, and another, muxan okox, "mushroom that makes the eater crazy" (from mox, meaning "mushroom" in the Mixe-Zoque languages of southern Mexico, and "crazy," or "falling into a swoon," in Cakchiquel-Maya of the Guatemalan highlands). Lyle Campbell (personal communication) and Terrence Kaufman, two linguists who have recently investigated the problem of linguistic diffusion in Mesoamerica, believe muxan okox to be one of several cases of linguistic borrowing of ritual terms from Mixe-Zoque into Maya languages in ancient times, perhaps as early as 1000 B.C., or even before. Since they also postulate Mixe-Zoque as the language of the Olmecs—the "mother culture" of Mesoamerican civilization —it is tempting to suggest that the Olmecs might have been instrumental in the spread of mushroom cults throughout Mesoamerica, as they seem to have been of other significant aspects of early Mexican civilization.

Mushroom Stones and the Cult of Sacred Mushrooms

Mention in several of the early sources on Guatemalan Maya languages of a mushroom specifically named for the underworld—i.e. the realm of the dead—is especially interesting in light of the discovery of a ceremonial cache of nine beautifully sculptured miniature mushroom stones and nine miniature metates (grinding stones),dating back some 2200 years, in a richly furnished tomb at Kaminaljáyu, a late Preclassic and Early Classic archaeological site near Guatemala City. The coincidence of the number of mushroom effigy sculptures interred with a Maya dignitary and the number of rulers of the traditional Maya underworld immediately impressed archaeologist Stephan de Borhegyi (1961), who proposed that the mushroom idols were almost certainly connected with the Nine Lords of X ibalba, as described in the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Quiche-Maya.

Stone effigies of mushrooms have in fact been turning up in archaeological contexts in Guatemala and Mexico since the nineteenth century. Borhegyi, who until his untimely accidental death in 1969 was director of the Public Museum of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, described, classified, and tentatively dated some 50 of these. More recently, a botanist, Bernard Lowy (1971), augmented the list with another 50, mainly from the highlands and Pacific slope of Guatemala. At this writing, Richard M. Rose, an anthropologist working on a classification of all known mushroom effigies, has catalogued more than 200, many dating to the first millennium B.C. The majority were found on Guatemalan soil, but others come from as far south as El Salvador and Honduras, and as far north as Veracruz and Guerrero in Mexico. Unfortunately, with a few notable exceptions, such as the nine miniature sculptures from Kaminaljóyu, the majority of these interesting effigies was not recovered under scientifically controlled conditions, so that reliable information on provenance and context is not usually available (Richard M. Rose, personal communication).

Connection between these sculptures and the historic mushroom cults of Mesoamerica has not always been accepted. Though many mushroom stones are quite faithful to nature, they were, until recently, not even universally thought to represent mushrooms at all, and a few diehards even now, in the face of all the evidence, reject this interpretation. When first reported in the nineteenth century, the sculptures were thought to be phallic symbols only, a theory that still crops up occasionally but that must be rejected as one-sidedly male-centered. To have any validity at all, the phallic element would have to be seen as one half of a male-female unity, in that the arrangement or juxtaposition of stem (male) and cap (female) in the mushroom fits well into the traditional Mesoamerican system of complementary opposites and the synthesis of male and female elements as the essential precondition for fertility and fecundity. (It is this concept that is expressed so well in Mesoamerican cosmology in the merging of a primordial male and female pair of creator gods into a single bisexual being.)

It was Carl Sapper who in 1898 first identified archaeological mushroom stones from Guatemala and El Salvador as idols of deities in the shape of mushrooms, rejecting, on obvious morphological grounds, the notion that they had served as phallic symbols in a fertility cult. Even now one hears it said that perhaps they were used as seats, or as territorial markers, or even that they might have been potter's tools that served for the making of molds for ceramic bowls. Of these, only for the marker opinion could one make some kind of argument—but even if a mushroom idol served anciently to mark the boundary of a community's land holdings, which in any event were considered sacred, it could have done so as idol of a guardian deity rather than as a property marker in the modern sense. In any case, refusal to recognize the sculptures as what they obviously are—mushroom idols—is likely to be a function of R. G. Wasson's ingenious division of people into those who loathe mushrooms and those who like them (or, in his terminology, mycophobes and mycophiles), a dichotomy that he relates to the history of sacred mushrooms in the lives of different populations since remote antiquity. Even without the visual evidence, one would have to explain away the fact that many of these sculptures, especially those that date between 1000 and 100 B.C., not only represent a naturalistic mushroom but also incorporate a human face or figure, or some mythic or real animal—toads and jaguars in particular—that merge with or project from the stem. The jaguar-mushroom association is especially interesting in light of the mention, in the Coto dictionary, of a mushroom called "jaguar ear." One of the most intriguing of these mushroom "idols" depicts the fungus emerging from the upturned mouth of a toad, apparently Bufo marinus, the venomous amphibian that in much of Middle America, and also in the South American tropics, stands for the divine earth as Mother Goddess in her monstrous, devouring animal manifestation (e.g. Tlaltecuhtli, "Owner of the Earth," the earth monster in Aztec cosmology, or Toad Mother Eaua Quinahi, also meaning Owner or Guardian of the Earth, of the Tacana Indians of Amazonian Bolivia [Furst, 1972b].) Wasson (1967a), in his previously quoted discussion of the crucial role of the doncella, or maiden, in the preparation of ritual hallucinogens, has drawn attention to another interesting synthesis of naturalistic and symbolic elements in a mushroom stone in a New York collection:

The cap of the mushroom carries the grooved ring that according to Stephan F. de Borhegyi is the hallmark of the early pre-Classier] period, perhaps B.C. 1000. The stone comes from the Highlands of Guatemala. Out of the stipe there leans forward a strong, eager, sensitive face, bending over an inclined plane. It was not until we had seen the doncella leaning over a metate and grinding the sacred mushrooms in Juxtlahuaca in 1960, that the explanation of the Namuth artifact came to us. The inclined plane in front of the leaning human figure must be a metate. It follows that the face must be that of a woman. Dr. Borhegyi and I went to see the artifact once more: it was a woman! A young woman, for hr breasts were only budding, a doncella. How exciting it is to make such a discovery as this: a theme that we find in the contemporary Mixteca, and in the Sierra Mazateca, and in the Zapotec country, is precisely the same as we find recorded in Jacinto de la Serna and in the records of the Santo Oficio. (p. 348)

Was the Fly-Agaric Sacred to the Maya?

Mushroom effigies of fired clay have also been found in Mexico, as well as South America. Wasson himself has in his collection a fine terracotta "mushroom priestess" in the Classic Veracruz style, probably from the middle of the first millennium A.D., and I have been able to identify a number of ceramic mushroom depictions in the 2000-year-old tomb art of western Mexico (Furst, 1973, 1974c).

Before we leave the archaeological evidence from Mesoamerica, there is one intriguing point to be made about the probable taxonomy of the various mushroom representations. The morphology of the west Mexican ones leaves little doubt that a species of Psilocybe is meant. Some of the clay effigies even emphasize the characteristic knob or bump in the center of the cap. Oddly enough, however—considering that there is no evidence that the genus Amanita was ever employed hallucinogenically in Mesoamerica—some Guatemalan mushroom stones seem less to resemble Psilocybe than Amanita muscaria, the fly-agaric of Siberian shamanism, which also grows in highland Guatemala and elsewhere in North America. On the other hand, the fact that the stem or stipe of the mushroom stones is usually thick like that of A. muscaria, and not spindly like that of Psilocybe, might be a function only of the sculptor's material, especially where the stipe is combined with a human or animal effigy. Perhaps there were formerly also wooden mushroom idols that more closely approximated the characteristics of Stropharia or Psilocybe mushrooms. In any event, the Quiche-Maya of the Guatemalan highlands are evidently well aware that A. muscaria is no ordinary mushroom but relates to the supernatural, what with the fact that they have named it cakuljá ikox (cakulja = lightning, ikox = mushroom) (Lowy, 1974, 188-l91). A. muscaria is thus related to the Quiche-Maya Lord of Lightning, Rajaw Cakulja, who also directs the dwarflike rain bringers, called chacs in former times but now generally Christianized (in name, not function) as angelitos, little angels.

The ceramic art of the Moche civilization of Peru (ca. 400 B.C.-A.D. 500) also includes a number of anthropomorphic mushroom effigies, as well as personages with mushroom headdresses, dating to the first centuries A.D. Even more interesting is a certain class of spectacular pendants of cast gold from northern Colombia and Panama, apparently representing a deity. Most are highly stylized, but they share one feture—a pair of hemispheric headdress ornaments that look vaguely like bells on an old-fashioned telephone. These had long mystified specialists in the prehistoric art of the region until Andre Emmerich (1965) published a convincing argument that they were pairs of mushrooms that had undergone a stylistic evolution from near-naturalism in earlier pieces to greater stylization, including loss of the stem, in the later ones. Paired mushroomlike head ornaments in fact also occur to the north, on archaeological figurines found in Jalisco, western Mexico. Little is known of pre-Hispanic mushroom use in South America, with the single exception of an early Jesuit report from Peru that the Yurimagua Indians, who have since become extinct, intoxicated themselves with a mushroom that was vaguely described as a "tree fungus."

It is fitting, in the developing story of the Mexican mushrooms, that recognition be given especially to the contribution of that scholarly amateur (in the original complimentary meaning of the word), R. Gordon Wasson. It was he and his late wife, Valentina P. Wasson, who in the mid-l950's rediscovered the living mushroom cult of Oaxacan Indians and brought it to the attention of the world, not only in the pages of Life and in scientific journals but in a remarkable book, Mushrooms, Russia and History (1957). In its pages Borhegyi and Wasson suggested a connection between the sacred mushrooms of Mexico and the prehistoric stone mushrooms of Guatemala—the first time that such a possibility had been considered in print. But this takes us slightly ahead of our story, which should properly begin in the sixteenth century when Sahaglin first described slender-stemmed hallucinogenic mushrooms with small round heads that the Aztecs called teonanacatl, flesh or food of the gods, which he said were usually taken with honey (as the Lacandón are also said to take them), and which could have either pleasant or frightening effects. Francisco Hernandez (1651) was more specific; he mentioned three different kinds of intoxicating mushrooms that were revered by the people of central Mexico at the time of the Conquest. In the seventeenth century Jacinto de la Sema and Ruiz de Alarcón were still perturbed by the continued survival of such mushrooms in indigenous ritual, but thereafter they pass out of the literature, without a single one having been identified botanically—so much ignored that the economic botanist Safford (1915) decided they had never existed at all and that teonanácatl must have been peyote!

Safford's ethnocentric verdict came to be widely accepted although it flew in the face of some very specific historic references (e.g. Sahagtin: "It grows on the plains, in the grass. The head is small and round, the stem long and slender"—a description that hardly fits the peyote cactus, which occurs only in the semi-arid northern high desert. One who disagreed was the aforementioned Dr. Reko, who insisted that the old sources were accurate and that the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms had in fact survived in remote mountain villages of Oaxaca.

Found at Last: A Living Mushroom Cult in Mexico

He was to be proved right in the late 1930's. In 1936 "Papa" Weitlaner encountered magic mushrooms for the first time in the country of the Mazatecs in Oaxaca. He sent a specimen to Reko, who forwarded it to the Harvard Botanical Museum, where unfortunately it arrived too badly deteriorated to be identified. In 1938, Weitlaner, his daughter Irmgard, and her future husband Jean Basset Johnson, on a field trip to Huautla de Jimenez became the first outsiders permitted to attend—though not participate in—an all-night curing ritual in which mushrooms were eaten. Johnson, who lost his life in North Africa in 1944, described the experience at a meeting of the Sociedad Mexicana de Antropologia in August 1938 and in a more extensive paper published by the Gothenburg Ethnographical Museum (1939).

Mushroom use, he wrote, appeared to be widespread in Mazatec country; shamans, or curers, used them primarily for the purpose of divining the cause of an illness, and during the session it was the mushrooms, which were held in great reverence, that were believed to speak, not the curer. Johnson also confirmed that not just one but several kinds of intoxicating mushrooms were known to the Indians.

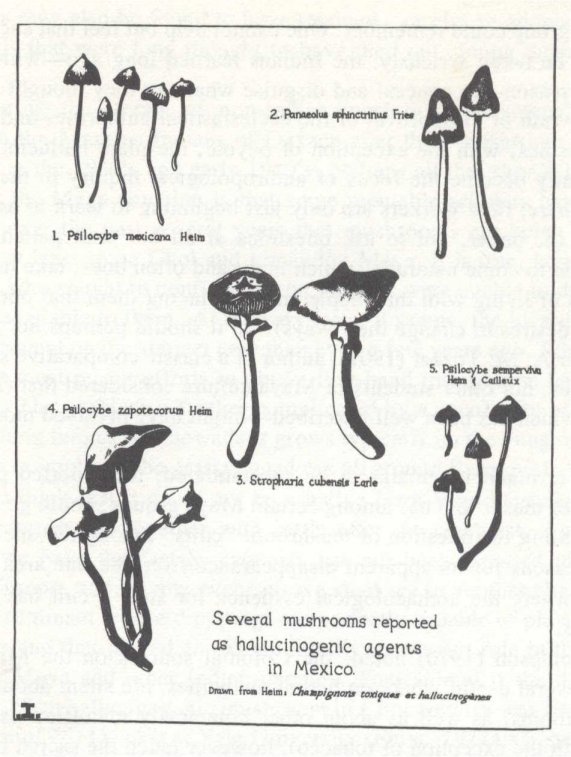

In August 1938, a month after the Weitlaner-Johnson experience at Huautla de Jimenez, Schultes and Reko received from Indian informants in the same village specimens of three different species they were told were revered by the people for their visionary properties. Schultes took careful notes of their morphology and in 1939 published the first scientific description. In 1956, the distinguished French mycologist Roger Heim, director of the Museum d'Histoire NatureIle in Paris, identified one as Psilocybe caerulescens; another was defined by the Harvard mycologist Dr. David Linder as Panaeolus campanulatus, subsequently redefined as P. sphinctrinus; and the third by Dr. Rolf Singer as Stropharia cubensis.

Schultes and Reko on their field trip in 1938 had also been able to extend the area of sacred mushroom use beyond the frontiers of Mazatec country to other Indian groups of southeastern Mexico. In the years since, more mushroom-using populations have been added to the list, including, as recently as 1970-l971, the Matlatzinca of San Francisco Oxtotilpan, a small town located about 25 miles southeast of Toluca in the state of Mexico, and possibly also the Chol and Lacandón in the Maya lowlands. The Matlatzinca, who belong to one of the oldest language families of Mexico, the Otomian, are the first inhabitants of central Mexico to have been identified with mushroom use since the sixteenth and seventeenth century, and the Chol and Lacandon are, as already noted, the very first Maya populations for whom sacred mushrooms have been reported in historic times. Altogether we now know of about fifteen different Indian groups, each with its own language, whose curers employ hallucinogenic mushrooms. There are likely to be still others, including lowland and perhaps even highland Maya-speakers, among whom the ancient practice will eventually be found to have survived.

"Mycophiles" and "Mycophobes"

In the meantime Mexican mushroom research had entered an entirely new and more public phase with the entry of the Wassons into the picture. Wasson was a banker, a vice president of J. P. Morgan & Co. in New York; his wife, Valentina Pavlovna (who died in 1958), was a Russian-born pediatrician. Wasson has often told the story of their deep personal stake in mushroom research, which received its initial impetus with his discovery, on their honeymoon, that he and she had assimilated from their different parental cultures very different—indeed, diametrically opposed—points of view toward mushrooms in general, and wild ones in particular:

A little thing, some will say, this difference in emotional attitude toward wild mushrooms. Yet my wife and I did not think so, and we devoted a part of our leisure hours for more than thirty years to dissecting it, defining it, and tracing it to its origin. Such discoveries as we have made, including the rediscovery of the religious role of the hallucinogenic mushrooms of Mexico, can be laid to our preoccupation with that cultural rift between my wife and me, between our respective peoples, between mycophilia and mycophobia (words we devised for the two attitudes), that divide the Indo-European peoples into two camps. (1972a:186)

In 1952, the Wassons first learned of the early Colonial descriptions of mushroom rites and their confirmation by Schultes and others in the late 1930's, and, simultaneously, of the remarkable archaeological artifacts called mushroom stones. In 1953 they plunged seriously into the problem, spurred on by a lengthy description of Mazatec mushroom practices they received from Miss Eunice Pike, a missionary linguist with the Wycliffe Bible Translators, who had spent several years among the Indians of Oaxaca. (See Pike and Cowan, 1939.) Belief in the sacred mushrooms was indeed widespread, she confirmed, but the Indians guarded their secrets well against strangers. As Johnson had reported in 1939, she wrote that pre-Christian and Christian religious concepts and terminologies were inextricably intermingled in the Oaxacan mushroom rites (as, indeed, they are everywhere else, with the exception of the Lacandón; Huichol peyote ritual is likewise essentially non-Christian in meaning and terminology). For example, the Mazatecs spoke of the mushrooms as the blood of Christ, because they were believed to grow only where a drop of Christ's blood had touched the earth; according to another tradition, the sacred mushrooms sprouted where a drop of Christ's spittle had moistened the earth and because of this it was Jesucristo himself that spoke and acted through the mushrooms. (Hofmann, 1964)*

"A Soul-Shattering Happening"

In 1953 the Wassons went to Oaxaca for the first time, but another two years passed before they were able to develop a sufficiently warm bond of trust with their Indian hosts to be permitted to partake of the sacred mushrooms. So, in 1955, Wasson and a companion, Alan Richardson, became the first outsiders to actually participate in a mushroom curing ceremony—an unforgettable experience, Wasson later reported, that was to profoundly affect him, who by his cultural inheritance had once utterly "rejected those repugnant fungal growths, manifestations of parasitism and decay" (1972a: 185).

In his enthusiasm for the extraordinary psychic effects of the mushrooms and other sacred halluginogens, Wasson would not be misunderstood as suggesting that these are, or were, the only means of attaining the ecstatic state. Clearly, poets, prophets, mystics, and ascetics

. . . seem to have enjoyed ecstatic visions that answer the requirements of the ancient Mysteries and that duplicate the mushroom agape of Mexico. I do not suggest that St. John of Patmos ate mushrooms in order to write the Book of the Revelation. Yet the succession of images in his vision, so clearly seen and yet such a phantasmagoria, means for me that he was in the same state as one bemushroomed. (1972a:196)

Nor would he suggest that Blake had to have taken mushrooms or some other natural hallucinogen in order to write that "he who does not imagine in stronger and better lineaments, and in stronger and better light than his perishing eye can see, does not imagine at all." Nevertheless,

• . . the advantage of the mushroom is that it puts many (if not all) within reach of this state without having to suffer the mortifications of Blake and St. John. It permits you to see, more clearly than our perishing mortal eye can see, vistas beyond the horizons of this life, to travel backward and forward in time, to enter other planes of existence, even (as the Indians say) to know God. . . . All that you see during this night has a pristine quality: the landscape, the edifices, the carvings, the animals—they look as though they had come straight from the Maker's workshop. (1972a:197-198)*

Wasson came away from what he later characterized as a profoundly soul-shattering happening, convinced that the magical powers the Indians had ascribed since ancient times to their revered mushrooms were very real indeed, and that chemistry alone could never fully account for the experience of an ineffable mystery, akin to those of the ancient Greeks, with the simultaneous participation of all the senses:

. . . the bemushroomed person is poised in space, a disembodied eye, invisible, incorporeal, seeing but not seen. In truth, he is the five senses disembodied, all of them keyed to the height of sensitivity and awareness, all of them blending into one another most strangely, until, utterly passive, he becomes a pure receptor, infinitely delicate, of sensations. (p. 198)

The Mosaic Completed

Nevertheless, Wasson was sufficiently a child of the scientific age not to leave it at that (he is, in fact, a meticulous and 'critical scholar and tireless researcher, as demonstrated by his extraordinary book on the identity of Soma [1968] and his latest work, the first definitive monograph on an Oaxacan mushroom rite [1974]). Even before his Mazatec mushroom experience he was in close contact with Roger Heim as one of the leading mycologists in the western world, and Heim now accompanied him on further expeditions into the mountains of Oaxaca, in consequence of which a dozen or so different mushrooms of the family Strophariaceae, mostly of the genus Psilocybe, but also of Conocybe and Stropharia, were identified. With the additional field work of Singer (1958) and the Mexican botanist Gastón Guzman-Huerta (1959a, b), by the end of the 1950's the mosaic of the sacred mushrooms of Mexico, completely unknown only twenty years earlier, was reasonably complete.

According to Schultes's summary of 1972, and his and Hofmann's collaborative monograph on the plant hallucinogens (1973), species of Psilocybe and Stropharia are the Most important, the most significant being apparently Psilocybe mexicana , P. caerulescens var. mazatecorum , P. caerulescens var. nigripes , P. yungensis ,* P. mixaeensis, P. hoogshagenii, P. aztecorum, P. muliercula, and Stropharia cubensis. Singer (1958) reported that his own work in Oaxaca failed to find Panaeolus sphinctrinus—one of the three hallucinogenic species the Indians gave Schultes and Reko in 1938—in the Mazatec inventory of sacred mushrooms. But as Schultes (1972a) points out, different shamans have their own favorite species and also tend to vary these according to seasonal availability and the precise purpose for which the mushroom is intended. Psilocybe mexicana, a small, tawny inhabitant of wet pasture lands, he writes, is probably the most important species utilized hallucinogenically in Mexico, but the strongest psychedelic effects seem to belong to Stropharia cubensis.

Heim was able to propagate a laboratory culture of the sacred mushrooms in Paris, but when attempts to isolate the active principles of Psilocybe mexicana proved unsuccessful, he submitted several specimens, as well as other species, to Hofmann for analysis at Sandoz. Hofmann was almost immediately successful in discovering the agents responsible for the extraordinary psychic effects of the mushrooms, and, shortly afterwards, in reproducing the chemicals synthetically without the aid of the plants themselves. The principal active agent was identified to be an acidic phosphoric acid ester of 4-hydroxydimethyltryptamine, allied to other naturally occurring organic compounds such as bufotenine and serotonin, and probably derived biogenetically from tryptophane. This he named psilocybine. Also present as an unstable derivative was a compound he called psilocine. The same constituents have been isolated from several North American and European mushroom species that are not used as hallucinogens and for which we have no indication that they were ever so employed (Schultes, 1972a:10).

The active agents of the sacred mushrooms, Hofmann reported, amount to about 0.03% of the total weight of the plants; to achieve the effect of as many as 30 mushrooms (only a few are actually used at a time in the rite) would require only 0.01 gram of the crystallized powder dissolved in water.

Hofmann (1964) has summarized the most important results of the phytochemical investigation of the sacred mushrooms as follows: Psilocybine and psilocine are chemically-structurally related to serotonin, a substance that occurs in the mammalian brain and that plays a role in the chemistry of brain function. The structural relationship of the active principles of the mushrooms with serotonin provides an explanation for their psychic effects, and offers insights into the biochemistry of the brain itself. The pharmacological phenomena are explainable in terms of central excitation of the sympathetic nervous system. In human subjects, doses of 6 to 20 milligrams bring about, without any physical symptoms worth mentioning, fundamental changes or transformations of consciousness, with wholly different perceptions of space, time, and one's psychic and bodily self. The sense of sight and also that of hearing are greatly heightened, to the point of visions and hallucinations. Not uncommonly, long-forgotten events, often those that belong to the realm of earliest childhood, manifest themselves with extraordinary clarity.

Although he was by no means finished with the phytochemistry of the mushrooms (for example, he himself, in the company of Wasson, was still to experience their wondrous mystical effects in a mushroom rite conducted by the famous Mazatec curing priestess Maria Sabina [Wasson et al. , 1974]), for Hofmann the stage was now set for his discovery in the divine morning glories of lysergic acid derivatives closely related to LSD—just as the synthethis of LSD in 1943 had led to the isolation of psilocybine and psilocine in the sacred mushrooms.

*Although the species name appears to identify this psychedelic mushroom with Cuba, it should not be taken to mean that it is, or originally was, native only to that island or the Caribbean in general. Rather, it was so designated because it was first described in 1906 by F. S. Earle after encountering it in Cuba. S. cubensis appears to be a New World variety found mainly—but not exclusively—in Mexico and parts of Guatemala; interestingly enough, a similar species, originally called Naematoloma caerulescens but subsequently assigned to the same genus as S. cubensis, was identified in 1907 in what is now North Vietnam. For the most recent discussion of the Psilocybin mushrooms, including S. cubensis, see Steven Hayden Pollock, M.D., "The Psilocybin Mushroom Pandemic," Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 73-84 (1975).

*My colleague Robert M. Carmack, one of the most knowledgeable of scholars in the field of highland Guatemalan ethnohistory and culture, to whom I am indebted for the mushroom references in early highland dictionaries, recently collected mushroom lore from a Quicheanspeaking elder, confirming that some of the ancient knowledge continues to survive.

*According to current terminology for the cultural phases of Mesoamerican prehistory this should be called Middle Formative. The dating is in any event only approximate.

*This belief seems to have its origin in indigenous shamanism. In Mexico, as everywhere else in shamanistic religion, supernatural and therapeutic power are attributed to the shaman's spittle, which is sometimes identified (as among the Papago of Arizona) as rock crystals in liquid form, rock crystals being near-universally regarded as crystallized spirits, usually of deceased shamans. Divine spittle is also related to the origin of the sacred mushroom in Siberia (see Chapter Eight).

*It is typical of the syncretistic nature of the present-day mushroom cult that some Oaxacan Indians say God gave them the sacred mushrooms because they could not read and it was necessary for him to speak to them directly through the mushrooms. Eunice Pike and her fellow missionary Florence Cowan (Pike and Cowan, 1959) have related how difficult it is to explain the Christian message to people who are convinced they already possess the means—the sacred mushrooms—to receive the word of God in immediate and vivid form, to visit heaven for themselves, and to establish direct contact with God. Readers interested in other sensitive accounts of the mushroom experience might consult, apart from Wasson's most recent work (1974), Henry Munn's essay in Hamer (1973).

*Schultes suggests that this might have been the species employed by the Yurimagua Indians of Peru.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|