Chapter 5 The Changing Dutch Heroin Culture: Past, Present, Future

| Books - From Chasing the Dragon to Chinezen |

Drug Abuse

Chapter 5 The Changing Dutch Heroin Culture: Past, Present, Future

The preceding two chapters examined the spread of the chasing ritual among Dutch heroin users from two different angles. Chapter 3 explored the factors that were involved in the diffusion process, while chapter 4 took a quantitative approach and investigated the resulting changes in the distribution of injecting and chasing in relation to heroin career onset dates. This chapter will shortly summarize the results and discuss these in the context of recent developments and international perspectives.

5.1 Summary of the Findings

The diffusion of chasing parallelled the introduction and spread of heroin use in the Netherlands. The introduction of heroin in the Netherlands has been associated with heroin overproduction in South East Asia, due to the end of the Vietnam war, the ready market of the 'hippie' subculture and the presence of a rather large Chinese community. While the first users of heroin mostly originated from this hippie subculture and predominantly injected the substance, a second user group with minimal prior drug experience --the Surinamese--- adopted chasing as their dominant selfadministration ritual. These people immigrated in large numbers to the Netherlands around the Independence of Suriname in 1975. In that period the economical crisis became tangible, while the availability and use of heroin expanded. Rapidly the Surinamese got involved in the use and trafficking of heroin. The involvement in heroin of the Surinamese immigrants has been explained in terms of ignorance about the substance, acculturation problems, unemployment and a culture specific reaction to these problems (street corner culture, hosselen), drug dealing connections of earlier immigrated countrymen and an ethnic link with the Chinese. It is reasoned that the Chinese taught the Surinamese to smoke heroin. Ensuing, explanations are presented for the fact that the Surinamese users did not proceed to injecting. These include a culturally based needle taboo, the social meaning (binding mechanism) of the chasing ritual and the absence of intensive contacts with IDUs. All these cultural factors could, however, not have operated without a co-occurring interaction of drug market and policy factors resulting in a stable availability of heroin at a purity level (± 40%) sufficient for chasing. The stable heroin availability over the last twenty years was also of great importance for the secondary diffusion of chasing, which was largely facilitated by contacts in specific clubs, a shift from street scenes to house address-based scenes and social learning processes. For a large part this socioeconomic stability can be attributed to Dutch drug policy. The comparably low repression of drug users and enforcement emphasis on the importation level of the drug trade created the situation in which a stable and fairly relaxed consumer market could emerge in which heroin is sold of reasonable quality and price.

This social historical analysis is not exhaustive. Some aspects have only been touched upon, due to a lack of information or the absence of comparable data. Geographical diffusion and differences between cities and/or rural areas could only be minimally addressed. Likewise, the role of the Moluccan drug users. Did they learn to chase from the Surinamese, the Dutch or could there have existed a direct relationship between the Chinese and the Moluccans, for example in towns with both a sizable Chinese and Moluccan community? Furthermore, the role of Antillean drug users remains unclear, although this group has, at least in the Dutch heroin subculture been rather closely related to the Surinamese. Other (unknown) factors may have been omitted. Future research may bring up additional explanations. A combination of ethnography, oral history and social historical research seems most appropriate for this purpose. Such research will surely be an interesting and worthwhile venture, as it will further enhance understanding of the unique Dutch situation regarding drug use.

The secondary analyses offer no reasons to reject the tested diffusion hypothesis. The alternative explanation concerning an 'inevitable addiction process' leading to increasingly efficient administration rituals can, however, be dismissed. Although, because of methodological limitations inherent to secondary analyses, they cannot be considered as definitive, the results of these secondary analyses lend support to the presented reconstruction of the diffusion of chasing in the Netherlands. These results indicate that non-injecting heroin use has been prevalent since the introduction of the drug. In the Netherlands, heroin --introduced in 1972-- was not the first opiate, used in a recreational fashion. Before its introduction, use of opium had been known for decades among Chinese immigrants and had spread rather rapidly during the second half of the 1960s among Dutch drug experimenters. It has been often assumed that, in contrast with the Chinese opium smokers, these Dutch users injected the opium.' While this may be the case for most, it is not likely that all of these users injected --smoking was not uncommon among Dutch opium users, Conversely, a number of the current injectors in the Amsterdam AIDS Cohort Study (AACS) had injected before the introduction of heroin. In addition to opium this largely concerned amphetamines and, to a lesser extent, other opiates, for example pharmaceutical morphine, originating from hospital or pharmacy thefts. The preheroin opium smokers may have been among the first heroin chasers. The secondary analyses corroborate the suggestion that chasing is not just a pre-injection phase in a heroin career, but an established ritual pattern, with intrinsic personal and social value --a culture in itself.

5.2 Discussion

5.2.1 Chasing: An Expanding Culture

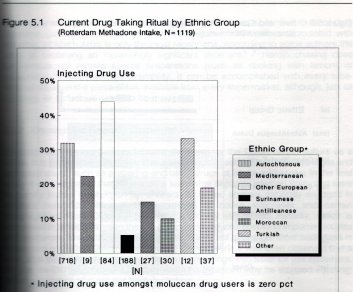

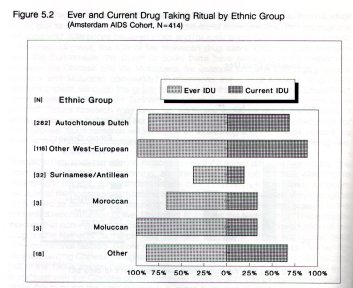

The autochtonic white Dutch --the subjects of the secondary analysis-- are only one of the ethnic groups the Dutch chasing culture entails. Among the allochtonic heroin users chasing is generally much more, and consequently injecting much less, common. Figures 5.1 and 5.2 present an overview of the prevalence of injecting of the different ethnic groups in the RMIS and AACS, before these datasets were matched.

Injecting prevalence is lowest among Surinamese users followed by the Moroccans, while among non resident users injecting is much more common, in particular among those from (European) countries with established drug injecting cultures.

As has become clear, the Surinamese have been the trendsetters for chasing and in their group the cultural norm of chasing is clearly the strongest. They are the group that (still) dominates consumption level dealing, Moroccans are also (increasingly) involved in (mostly street) dealing, but are relatively new in the scene and were never part of distinct, isolated networks, that rejected the traditional injecting culture, as were the Surinamese in the early 1970s -a time when many characteristics of the evolving heroin scene still had to take shape. In contrast, the Moroccans entered an arena in which most characteristics were cristallized out and positions taken. Their development of rituals and rules is therefore not only shorter, but also subject to more diverse influences. They mingled with various (ethnic) groups, with differing attitudes towards injecting. This explanation is supported by data from Korf and Hoogenhout on the composition of the friendship and acquaintance networks of the drug users in their study. The networks of autochtonic respondents consisted for 21% of allochtones. 25% of the Surinamese respondents' networks were nonSurinamese, mostly autochtones.

The proportion non-Moroccan friends and acquaintances of the Moroccan respondents was more than twice as high, 53%. Of these, 54% were autochtonic Dutch and 46% Surinamese.2

These data add to the understanding of the importance of both the socioeconomic and sociocultural factors involved in the diffusion process. The delicate interplay of these factors over the course of twenty years has changed the layout of the Dutch 'heroin culture' tremendously. Nowadays, this culture consists basically of two subcultures --injectors and chasers. The former was originally the largest and dominant one, and had its roots in the pre-1972 subcultures of (poly) drug experimenters. The latter started more or less as an imported exotic seedling, but proved to be extremely adaptive to the Dutch climate and highly expansive. It may have suffered and lost some leaves from the temporary droughts in the second half of the 1970s, when heroin prices skyrocketed up to 2000 a gram, but overall the conditions were favorable. Twenty years after sowing, it is overgrowing its thorny but withering complement. In 1990 only 18% of the new clients of the Amsterdam methadone programs injected, whereas in 1987/88 this percentage still was 25.6%. Looking back, the expansion of chasing is not surprising. Not only could it grow in a protected environment during the first years after its introduction (in the closed subculture of Surinamese users), it also had some marked advantages over injecting, which made it far more attractive to (especially novice) users. it is a rather familiar route of drug ingestion (smoking), without many of the negative connotations associated with injecting, of which AIDS is only the most recent one. According to some authors the latter is becoming an increasingly significant deterrent.s 6 Heroin chasing does furthermore not require special preparations (such as cooking with lemon) or paraphernalia with restricted availability. It can be accomplished with every tubeshaped object and a piece of foil, available from every supermarket, although, just as injecting, its technique needs to be mastered.

5.2.2 Chasing: The Reigning Subcultural Norm

Chasing has thus increasingly become the norm for the Dutch heroin culture as a whole. It is associated with higher status and provides access to explicit privileges and restricted areas, such as preparing and using drugs at house addresses. In the field study it was observed that IDUs took a somewhat separate position from, and were frequently looked down upon by, chasers. IDUs and chasers generally engaged in different networks, although these crossed at house addresses and certain congregation sites. IDUs are becoming a doubly stigmatized minority, which is expressed in tension between the two groups and reduced access to important locales and resources. Preparing and taking an injection is not allowed at most addresses in Rotterdam and other Dutch cities.6 During the fieldwork, it was even observed that a user, after buying heroin, was prohibited to fill his syringe with water for use elsewhere. As one 'ex-IDU' expressed it painfully when he explained why he stopped injecting: "When you inject, you are not really welcome".

The strength of the chasing norm is further indicated by the observation that foreign users ---whoin majority come from (Western European) countries with injecting cultures--- adapt to it. In a longitudinal study of 'drug tourists' in Amsterdam injecting heroin use decreased from 84% to 74% and cocaine injection from 75% to 66%. 7 Moreover, foreigners that first used heroin in Amsterdam did so by injection in only a quarter of cases, against two thirds of those that started in their homeland. Life time injecting prevalence among those who started in Amsterdam is five times lower.'

5.2.3 Recent Developments: Compliance to, and Evasion of, a Pressing Cultural Norm

The shift towards chasing has also been reported in other Dutch studies. Grapendaal and colleagues suggested a 19% decrease in injecting after a one year follow up (from 43% of 148 users to 35% of 89 users).9 At the other hand, Korf and colleagues observed a small (non significant) increase in injecting. Likewise, the Rotterdam field study presented data on transitions between administration rituals in both directions, within a minority of subjects." Hartgers and colleagues studied changes over time from 1985 to 1989 in drug use patterns among 386 IDUs (defined as having injected at least once at some previous time) in four consecutive intake groups of the Amsterdam AIDS Cohort Study. A larger proportion of respondents in the later intake groups were smoking heroin and 'freebasing' cocaine.' While they found no overall indications of changes over time in 'current' (at least once within the last six months) and 'current daily' injecting, their data indicated a decrease in daily injecting among cocaine smoking subjects." Compatible results were reported by de Loor, who recently interviewed 94 (self-defined) IDUs in seven Dutch cities.6 He found a decreasing popularity of injecting and described, what he calls the 'varia pattern', in which various drugs have become part of the consumption pattern and the route of ingestion is not only determined by the drug, but also by the circumstances. As main reasons for this varia pattern, de Loor gives pragmatic motives, such as management of drug use (i.c. leveling off the amplitude of the six hour injecting cycle) and 'passing' in the sense of Goffman's 'discreditable' 12 in scenes of smokers (who often disrespect injectors). According to de Loor, this pattern is an expression of a general drugs trend, representing increasing individualization of drug use, which leads to a decline of scene identity, and the value of the associated symbols, rituals and clear scene codes.'

All these studies have however some limitations wherefore it remains unclear what their implications are for the larger heroin using population. Korf and Grapendaal only minimally address the issue, and in the Rotterdam field study transitions between administration rituals were neither a main topic. De Loor's report contains several important observations and assumptions but unfortunately he repeatedly falls short in supporting his argument. His explanations tend somewhat towards circular reasoning and he furthermore makes (methodologically) debatable generalizations from 'street circuit' IDUs, to IDUs in general, and, in particular, to non-IDUs, whom he did not interview.6 This limits the representativeness of his findings. Likewise, Hartgers and colleagues contended that the representativeness of their study may also be limited. Not only does their sample differ from the larger population of methadone clients in terms of a low proportion of males and a rather high injecting prevalence, but as Korf showed, Amsterdam methadone users, and more specific, methadone clients are more often IDUs, than users that do not take methadone. 2 Furthermore, as Hangers and colleagues studied HIV risk behavior, their definitions of IDU and current IDU were rather broad. For example, the criterium of current injector (having injected at least once in the last six months) will be met by both the daily IDUs and the smoker, who in this period made one exception to her/is normal routine."

While the general trend indicates a dominant chasing pattern, the picture that arises from these studies suggests some diversification of patterns. A number of users clearly switch (regularly) between smoking and injecting or practice both rituals, although the present study as well as the studies by Korf and colleagues and Grapendaal and colleagues suggest that these are a minority.2 9 Against the background of the AIDS epidemic, the correllation between the self-definition of these users regarding their route of drug taking and their actual behavior becomes an important issue with major consequences in terms of HIV prevention activities.

Are they IDUs who smoke some of the time (thereby lowering their risk of contracting HIV), or are they chasers that occasionally inject? Are they IDUs who conform to a pressing cultural norm, or are they smokers that (secretly) break that same cultural norm? In fact, little is currently known of the details, scale and nature of both kind of transitions. The lack of such data becomes increasingly pressing.

5.2.4 Transitions between Administration Rituals and Cocaine Use

There are several indications that cocaine plays a role in transitions between administration rituals. The Rotterdam field study suggested that a certain number of transitions to injecting (which may be confined to certain subpopulations) may for a considerable part be associated with cocaine use.10 Two studies by Korf and colleagues also suggest a role for cocaine --both studies reported a higher prevalence of cocaine injection compared to heroin injection. 2 13 In the preceding secondary analyses injecting is not only more prevalent among subjects that use cocaine (48% v.s. 36%), use of cocaine was also the strongest discriminator in respect to injecting in the AACS. Therefore the effect of cocaine use at the time of first injection has been examined in the AACS. Figure 5.3 displays the results of this analysis. The figure shows, first of all, a general decrease of the interval between first heroin/opiate use

and first injection. Secondly, among ever IDUs that used cocaine at the time they first injected, the time-lapse from heroin career onset to injection was longer than for those not using cocaine at the time.' This effect is especially present during the 1970s. From the early 1980s on, when cocaine became widely available in the heroin scene, the difference diminished. It might therefore be possible that the group starting injection while they also used cocaine at the time, had already a reasonable opiate career length (in particular the cases at the left side of the graph) and would never have started injecting without cocaine. On the other hand, those ever IDUs not using cocaine at the time of first injecting, might have been determined to injection drug use anyway. This effect could be interpreted in terms of the 'subjective availability' of cocaine. Due to the combination of craving for the cocaine high and its short lasting effect, the subjective availability of cocaine can be viewed as much lower than that of heroin and this economic pressure may push people towards injecting. Hedonistic reasons can, however, also play a role, as a 'plezier shotje' (a little pleasure shot) cocaine is not really exceptional among chasers, because "that is so nice!". This occasional delight is, nevertheless often kept a secret.

5.2.5 Cocaine Basing: Risk Factor or Protective Factor for Injecting?

The renewed popularity of basing may also play a role in this matter. In their longitudinal study in Amsterdam, Korf and colleagues not only established an increase in cocaine injecting, but also in cocaine basing. The rising prevalence of basing is a rather recent phenomenon. In Rotterdam basing (suddenly) became popular in the summer of 1988.'(' It was primarily observed at house addresses, where people smoked 'from the glass' and, to a lesser extent, from commercial base pipes. Since then an increasing number of chasers started basing cocaine and the practice diffused to the street-oriented populations. These street users adapted the basing ritual to the requirements of the street. They replaced the bulky water glass and glass basepipe for pocket size self-constructed pipes, which are easy to carry and allow for smoking in less stable environments. In Rotterdam, basing is currently practiced by most cocaine using chasers, while they continue to chase heroin (and cocaine). Anecdotal reports indicate that an increasing number of IDUs also seem to utilize this method. Over a period of approximately two years basing grew from, as one study participant called it, "a kind of a fashion whim" to a firmly established pattern. The suggestion of Grapendaal and colleagues that basing is an infrequently utilized mode of consumption, may therefore merely reflect local (network) differences or that this practice had not yet catched on locally in the time they collected their data.9

The intriguing question is, of course, how to consider basing --is it a risk factor or a preventive factor for injecting drug use (and subsequently HIV infection)? The Rotterdam field study and the studies of Korf and colleagues tend to support the suggestion that basing may be a precursor for the transition to injecting. But the previously cited study by Hartgers and colleagues related the higher prevalence of cocaine smoking/freebasing in their later intake groups to a lower prevalence of current daily injecting.' In that case basing would be a protective factor for injecting. However, the freebasers in the Hartgers et al. study started injecting more recently, most of them smoked heroin and only one in eight is injecting daily. Taking their broad criterium of current user into consideration, could these subject not be (self defined) smokers, who via basing are progressing towards injecting? It is clear that there remains much to be said (and asked) on the relationships between cocaine use and the (transitions between) administration rituals. This, however, requires further research, tailored to the research questions.

It has become clear that drug taking rituals are not static condit ons. T e c asing norm obviously influences the drug taking patterns of IDUs, who seem to adapt to it. The available evidence also suggests that chasers, may break the same norm. As suggested by the preceding discussion, the cultural supremacy of the chasing culture in the heroin scene can, in this respect, be seen to create its own (secret) deviants. 14

5.2.6 The Dutch Situation in International Perspective

In the US, opium smoking was introduced by Chinese contract laborers in the midnineteenth century and during this period the drug was also an indispensable ingredient of a variety of widely used 'patent medicines'. After a federal law against importation of prepared smoking opium was passed in 1909 and the availability of smoking opium significantly decreased, many opium smokers turned to (injecting) morphine and heroin, which could be legally obtained until the Harrison Narcotic Act was passed in 1915. 15 16 17

Using the concept of diffusion, O'Donnell and Jones explained the spread of the intravenous technique among American opiate users in the first half of this century." Intravenous (IV) injecting (nowadays the most common parenteral route in the USA) seems to have started in the US around 1925, spread quite slowly until the early 1930s and by 1945 had become widespread. IV injecting was particularly favored, and far more frequent among drug users who had used heroin, who took the drug for 'kicks' -as opposed to those who had started drug use in the context of medical treatment-and who had become addicted before age 30. Until the 1920s parenteral drug use was largely contained to iatrogenic users, who generally injected subcutaneous or intramuscularly, while subcultural (recreational) heroin users were, even until 1925, mostly sniffing.

According to O'Donnell and Jones, hedonistic users started shifting to intramuscular or subcutaneous injection during the early 1920, but IV use began when the heroin began to be diluted. Before that time, hitting a vein was often considered an accident and viewed as dangerous, and sometimes fatal. Taking into consideration the --by today's standards-- enormous doses this does not seem incomprehensible. O'Donnell

and Jones suggest that such accidental IV injections by 'kicks users' were at the start of the diffusion of this technique in the US --either from one central place or from several or many places. After recovery from the fright (and, presumably, near overdose) the IDU decided that there was some pleasure in the experience and deliberately repeated it, using a smaller dose. If this resulted in a positive experience, this was communicated to using friends, upon which they would try it. Once (IV) injecting was adopted, it tended to continue, with only few users shifting away from this most efficient route. Similar to the findings in Rotterdam,10 shifts away from the IV route seemed, related to used up veins, whereas users explained their preference for injecting in terms of hedonistic motives, in particular the rush experience. Clearly, the increasingly low purity did not favor transitions back to non-injecting routes of use. As one of the subjects of O'Donnell and Jones explained, "you didn't need no vein until they cut it".18

Recently Des Jarlais, Courtwright and Joseph highlighted some factors why American opium smokers did not initiate heroin smoking, but, instead, gradually but massively, turned to injecting.19 Their analysis strongly emphasizes factors that impact on the availability of both drugs. In their view, heroin smoking has not developed in the US due to (1) the mechanics of smoking, which requires a purer drug preparation -smoking is less effective than injecting; (2) two aspects of the operation of the illicit distribution system for heroin in the, US, which resulted in a heroin quality at the consumption level insufficient for smoking;* and, (3) a lack of treatment during the transition. The importance of the first factor is extensively discussed in chapter 3. Regarding the second, the authors explained that (A) heroin became increasingly adulterated as a result of stricter international controls, world war 11, and the shift in illicit heroin distribution from Jewish-dominated criminal organizations to a monopoly of their Italian counterparts. (B) The law enforcement tactics employed against heroin use and distribution focussed on the users and low-level distributors. "The practice of vigorously enforcing laws against the low-level dealers helped to maintain the monopoly of the Italiandominated criminal organizations and created an incentive for multiple levels of distribution at the lower end of the system." Almost exactly the opposite can be seen in the Dutch drug arena during the preceding two decades. Different (ethnic) groups compete and cooperate on the illicit drug markets, while their degree of organization does not even approach that of the American-Italian criminal organizations. As a result of the relative tolerance of consumptionlevel dealing, the stratification at the lower end of the distribution chain --and thus the number of links in the chain between the dealer and the consumer-- is comparably low and the incentive to dilute the product is proportionately small.

Finally, lack of drug treatment during the transition from opium smoking to heroin injection and onwards guaranteed an inelastic market for drug distributors and forced users to accept low drug purity.'9 The little treatment available was not only unsuccessful in keeping users off drugs, it did not have any impact on the illicit market. Unlike in the Dutch situation of the last 20 years, (methadone maintenance) treatment did not offer a viable alternative for the black market, when the demands and pressures of maintaining personal use levels became unsurmountable. Clearly, dealers with monopoly power give less value for money and do not have to market their product or maintain good terms with their customers. The Dutch argot words 'betermakertje' (a little dose to ameliorate withdrawal) and 'mazzeltje' (a little luck) are in this respect significant semantical symbols for the rather symbiotic relationship between Dutch heroin users and their dealers. The easy availability of (low threshold) methadone (maintenance programs) in the Netherlands, and its effect on the relative dependence of Dutch users on the black market may be called one of the major positive effects of the Dutch treatment system. As O'Donnell and Jones contended, besides these economic factors, involvement in a drug subculture is equally important. In both the diffusion of IV injecting in the US and the diffusion of smoking in the Netherlands evidence of subcultural developments is unequivocally established.

While in the Netherlands heroin smoking emerged in the early 1970s, at the start of the following decade the first signs of a similar development in Britain started to arouse public attention. In 1978/79 Iranian base heroin began flooding the British market. 20 This brown heroin was particularly suitable for smoking and, compared to the still available South East Asian white heroin, which previously dominated the (much smaller) market, cheap. In some areas heroin smoking spread very rapidly. By 1985, in the Wirral (Northern England) around 95% of the plus/minus 5000 new heroin users were taking the drug by inhalation." Another study in Northern England found, however, major differences in the drug taking patterns from one town to another, presumably related to whether the pre-existing local drug subcultures favored injecting or snorting amphetamine."

The London based Drugs Transition Study Group recently published data on the transitions between routes of heroin administration. Their results indicate that up to the late 1970, injection was the main route of initiation among London heroin users, but by 1979 there were as many initiations by chasing as by injecting. By 1981 over 50%, by 1985 more than three quarters, and since 1988 94% were by chasing. 23 In a sample of 264 drug clinic attendants, in 52% injection, and in 48% chasing was the usual route. Injectors had taken their first injection on average within 1.5 years of first heroin and 90% of heroin injectors made this transition within four years. Almost half did so within the year of initiation into heroin use. Injectors were older and had used drugs longer than chasers. However, the average career of chasers was five years. Within the chasing group a considerable number had previously injected -36% at least once in the last year and 49% had life time experience. 24 These results show remarkable similarities with the results of the secondary analyses presented in the previous chapter. Comparison shows that transitions in London occurred somewhat more rapidly. The Dutch subjects were about three to four years older, but the age differences between IDUs and smokers did not differ much in the two cities. The same holds for the length of the heroin career --London IDUs: 7 years, smokers 5 years; AACS IDUs: 10.5 years, smokers 8.8 years. The age differences between injectors and smokers are 2 (London) versus 1.7 (Amsterdam) years. This comparison confirms the assumption that large scale heroin use is of more recent date in England and suggests that chasing is a more stable phenomenon and a more widespread cultural norm in the Netherlands.

There seem several other similarities between the Dutch and English developments around the introduction and diffusion of heroin smoking. Just as in Holland, the large scale introduction of the smoking ritual coincided with the introduction of abundant supplies of (in the English case a new type of) heroin to new user groups and a rapid increase of heroin use prevalence. Ethnic factors in the popularization of chasing seem also comparable to a certain degree. Griffiths suggested a role of the Chinese community in London's China Town. The prevalence of injecting among the West Indian/Afro-Caribbean subjects in the London Drug Transitions Study was significantly lower than among whites, while these groups are also associated with (consumption level) drug trafficking. A further obvious parallel can be found in the general socioeconomic situation of both countries and its experience by the new user groups. Mass (youth) unemployment was a main characteristic of the Surinamese, but also among the other people that started using during the 1970s and 1980s. According to several British authors, unemployment played a significant role in the 1980s heroin epidem ic . 21

Paraphrasing Des Jarlais, Courtwright and Joseph, the Dutch policy formed the legal and economic environment in which chasing became the predominant administration ritual in the nonmedical use of heroin and --in this population-cocaine. And using the words of O'Donnell and Jones, the (Surinamese) drug subculture furnished the 'specific channels of communication" the 'social structure and the 'system of values' which facilitated the spread of chasing.

5.2.7 Future Developments

Des Jarlais, Courtwright and Joseph contemplated on the possibility of near future large scale transitions from smoking to injecting in the USA, the Netherlands and England." When in the US treatment would remain unavailable, while the supply of crack would be reduced but not eliminated, many crack smokers, they predict, might turn to injecting. However, currently the availability of crack in the US remains rather stable, while the availability of high purity heroin is increasing. Preliminary and anecdotal reports suggest both an increase in heroin sniffing and the emergence of chasing." 11 2" The authors' suggestion that English and Dutch heroin smokers may turn to injecting is likewise not substantiated by the presently available information. The preceding analyses and the British data suggest fairly stable smoking cultures in both countries.

Nevertheless, some caution is advised. Although the Dutch heroin smoking culture at large seems sturdy enough to withstand the pressures of cocaine, it is clear that the current intensive cocaine use levels among heroin users affect the homeostasis in this group --leading to loss of control of many users, which may well be the cause of a certain number of transitions to injecting.10 In this respect, the younger and less developed British heroin smoking culture might well experience greater problems in maintaining its position. In regards to cocaine use, the current British situation seems to resemble the Dutch situation of the early 1980s, just before cocaine use boomed and the drug was still considered a frill by most heroin users.

In a 1990 study, the previously mentioned London based research group found 18% cocaine users among clients of a community drug team .29 Their more recent study of 200 heroin users suggests a rapid increase in cocaine use in this population, 37% had used cocaine on a daily basis in the year prior to interview. But these users experienced no or only minimal dependence problems in terms of self-reported 'severity of dependence' scores." In the Netherlands, where cocaine is widely available, such unproblematic use patterns seem only prevalent in, so called, 'nondeviant' users, who are generally not involved in heroin use. 3 31 However, in the heroin using population (daily) use is at least twice as high as in the london study, while considerable differences exist between ethnic groups and treatment v.s. non-treatment populations. In the Rotterdam field study 96% of the observed research participants, used both heroin and cocaine,10 while during the period from 1988 to 1990 about 70% of the Rotterdam treatment population used cocaine at intake .3 2 The Rotterdam study established the changed status of cocaine in this population. While it has become the drug of first choice for the majority of users, it is also causing the most problems." Interesting for the British situation is that the associated problems became only apparent several years after the 'cocaine boom'.

5.3 Conclusions

5.3.1 Drug policy: A Major Determinant of Drug Culture

As formulated by Des Jarlais, Courtwright and Joseph, "[p]olicy choices form the environment in which illicit drug use patterns will evolve, but do not completely determine those patterns".19 The presented analysis of the diffusion of chasing in the Netherlands strongly suggests an important structuring role for drug policy in the formation of the chasing culture. Drug policy thus shapes both the economy and the culture around the use of (illicit) drugs. It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that the absence of a smoking culture in the USA, and the relative age and strength of the British and Dutch heroin smoking cultures (In Holland a longer established dominant and stabler pattern in terms of rate and time interval of transition to injecting, while in Britain a more recently established, secondary pattern with considerable regional differences) are for a large part related to the diverging drug policies in the three countries, resulting in obvious differences in the level of socio-legal repression and the resulting impact on drug availability. Whereas such assumptions can only be definitively confirmed by carefully designed crosscomparative research, the proposed relationship may well be a crucial factor in the discussed differences between the three countries.

5.3.2 The AIDS Era: A Time for Fundamental Reconsiderations

The advent of the HIV epidemic forces society to reexamine the paradigms around drug use. 33 Globally, drug policy has largely been aimed at the eradication of the use of certain drugs. Nowadays it has become abundantly clear that this is not a realistic option, but merely wishful thinking, based on moral convictions. In the Netherlands this realization has been translated into a non-moralistic, pragmatic policy, aimed at containment and management of problematic drug use." This has not only resulted in a stabilization of heroin use, but also led to the emergence of a less harmful heroin use pattern. Largely unintendedly the Dutch policy shaped the environment in which (socialization into) heroin use is much more likely to occur in networks which support chasing (and reject injecting).

In the beginning of the 1990s, one can witness a general growth of the importance of public health perspectives in addressing socio-medical problems. In the field of drug use this development is represented by the increasingly utilized 'Harm Reduction Perspective' which gives a priority to prevention and treatment of (secondary) health problems of drug use, over termination of drug use itself. 35 From a public health perspective, the current Dutch situation is a fortunate one. Indeed, the low number of IDUs in the Netherlands --which has important implications for the HIV epidemic-- can be interpreted as a positive consequence of Dutch drug policy.

Furthermore, recent English research suggested clear differences in dependency levels associated with different administration rituals --chasers seem to experience significantly lower dependency levels.30 Such research has not been undertaken in the Netherlands, but the author's (anecdotal) observations of several 'generations' of heroin users are certainly in line with these results. It was for example observed that heroin users of later generations (those who started using in the 1980s), who were primarily chasers, experienced less problems in permanently quitting the use of heroin. Similarly, recent anecdotal reports on controlled heroin smoking among young Moroccans in Amsterdam may also be an indication of the difference found in the English study. Strangely enough, interest in administration rituals has been minimally in the Netherlands. The absence of this variable in national and local registration systems of drug treatment data speaks, in this respect, for itself.

5.3.3 Revitalizing Dutch Drug Policy: From Problem Management to Manipulating Cultural Values

When the socio-political conditions do not regress, the diffusion of the chasing ritual is likely to continue and one can even foresee that through a more active normalization and harm reduction policy this process can be reinforced. This would require sophisticated strategies and innovative interventions. From containment of problematic drug use and management of drug related problems, the leading policy incentive should be shifted towards actively trying to influence the nature of drug use and directing drug using cultures towards less harmful patterns of use. Examples to be studied are alcohol moderation, smoking prevention and other health promotion campaigns. One must understand that such a policy transcends the use of heroin and/or cocaine and should entail all drug use, be it legal or illegal. Such an innovative drug policy should furthermore be embedded in a broader framework of economic and social policy.

Regarding the use of heroin and cocaine, such a policy would support measures which promote smoking and sniffing, while discouraging injecting, however, without creating unintended situations, in which unsafe injecting practices become opportune. Concretely this would mean, that while maintaining and where necessary improving

services such as free needle distribution/exchange, smokeable drugs would be made easier available. Consequently, large scale availability of injectable drugs (e.g. prescribed injectable methadone) is contra-indicated. Likewise, in the current discussion around sanctuaries (places where use of hard drugs is tolerated), this would imply creating minimal services for IDUs including sufficient health care provisions, while creating more attractive (and probably separate) venues for smokers.

. Hartgers et al. speak of "cocaine freebasing", but do not distinguish between chasing cocaine and actual basing (from a pipe).

Resp.: 3.3 years, std.dev. = 3.3 and 1 .5 years, std.dev. = 2.4; t - -4.76, df = 239, p < .001.

. The authors actually speak of an increase in freebasing and heroin smoking and a decrease in current daily injecting. This is, however, somewhat confusing as their analysis concerns different intake groups.

. With quality the authors probably mean purity as they do neither discuss or specify the form of the compound (base or salt), nor the influence of different adulterants.

5.4 References

1 . Kort M de, Korf D: The development of drug trade and drug control in The Netherlands: A

historical perspective. Crime, Law and Social Change 1992; 17: 123-144.

2. Korf DJ, Hoogenhout HPH: Zoden aan de dijk: Heroinegebruikers en hun ervaringen met en

waardering van de Amsterdamse drugshulpverlening. Amsterdam: Instituut voor Sociale Geografie, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 1990.

3. Korf DJ, Kort M de: Drugshandel en drugsbestrijding. Amsterdam: Criminologisch Instituut

Bonger, UVA, 1990.

4. Buning EC: De GG&GD en het drugprobleem in cijfers deel IV. Amsterdam: GG&GD, 1990. 5. Ghodse AH, Tregenza G, Li M: Effect of fear of AIDS on sharing of injection equipment among

drug abusers. BMJ 1987; 295: 698-699.

6. Loor A de: AIDS preventie begint niet bij de buren. Een pleidooi voor een andere aanpak van

de distributie van spuiten. Amsterdam: Adviesburo Drugs, 1991.

7. Korf DJ: Heroinetoerisme 11: Resultaten van een veldonderzoek onder 382 buitenlandse

dagelijkse opiaatgebruikers in Amsterdam. Amsterdam: ISG, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 1987.

8. Korf DJ: "Heroin Touristen": Eine explorative Feldstudie uber auslandische tagliche

Opiatgebraucher in Amsterdam- Wiener Zeitschrift fur Suchtforschung 1986; 9(3): 3-13.

9. Grapendaal M, Leuw E, Nelen JM: De economie van het drugsbestaan: Criminaliteit als

expressie van levensstijl en loopbaan. Arnhem: Gouda Quint, 1991.

10. Grund J-PC: Drug Use as a Social Ritual: Functionality, Symbolism and Determinants of Self

Regulation. (forthcoming)

it. Hangers C, Hoek JAR van den, Krijnen P, Brussel GHA, Coutinho RA: Changes over time in

heroin and cocaine use among injecting drug users in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985-1989. British Journal of Addiction 1991; 86: 1091-1097.

12. Goff man E: Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon and

Schuster, Inc., 1963.

13. Korf DJ, Aalderen H van, Hogenhout HPH, Sandwijk JP: Gooise Geneugten: Legaal en illegaal

drugsgebruik (in de regio). Amsterdam: SPCP Amsterdam, 1990.

14. Becker HS: Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: The Free Press, 1973. 15. Brecher EM and the edotors of consumer reports: Licit and Illicit Drugs. Boston, Toronto: Little

Brown and Company, 1972.

16. Courtwright DT: Dark Paradise: opiate addiction in America before 1940. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press, 1982.

17. Musto DF: The American Disease: Origins of narcotic control. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press, 1973.

18. O'Donnell JA, Jones JP: Diffusion of the intravenous technique among narcotic addicts in the

United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 1968; 9:120-130.

19. Des Jarlais DC, Courtwright DT, Joseph H: The transition from opium smoking to heroin injection in the United States. AIDS & Public Policy Journal 1991; 6(2): 88-90 20. Lewis R: Serious Business --The Global Heroin Economy. In: Henman AR, Lewis R, Malyon T (eds.): Big Deal. The politics of the illicit drug business. London: Pluto Press, 1985, pp. 1-49. 21. Parker H, Newcombe R, Bakx K: The new heroin users: prevalence and characteristics in Wirral, Merseyside. British Journal of Addiction 1987; 82: 147-157. 22. Pearson G, Gilman M, McIver S: Young people and heroin. Aldershot: Gower, 1987. 23. Strang J, Griffiths P, Powis B, Gossop M: First use of heroin: changes in route of administration over time, BMJ 1992: 304: 1222-1223. 24. Griffiths P, Gossop M, Powis B, Strang J: Extent and nature of transitions of route among heroin addicts in treatment --preliminary data from the Drug Transitions Study. British Journal of Addiction 1992; 87: 485-491. 25, Griffiths P: Unpublished manuscript. 26. Frank B, Galea J, Simeone R: Drug use trends in New York City December 1990. New York, New York: New York State Division of Substance Abuse Services, 1990. 27. Treaster JB: Cocaine users adding heroin and a plague to their menus. The New York Times, July 21, 1990. 28. Liu M: The curse of 'China White'. Newsweek 14-10-199 1, pp 10-16. 29. Strang J, Griffiths P, Gossop M: Crack and cocaine use in South London drug addicts: 1987 1989. British Journal of Addiction 1990, 85: 193-196. 30. Gossop M, Griffiths P, Powls B, Strang J: Severity of dependence and route of administration of heroin, cocaine and amphetamines. British Journal of addiction (in press). 31. Cohen P: Cocaine use in Amsterdam in non-deviant subcultures. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 1989. 32. Toet J: Het RODIS onder de loep: Sexe-verschillen, veroudering en nieuwkomers in de Rotterdamse drugshulpvedening. Rotterdam: GGD-Rotterdam e.o., 1991. 33. Strang J, Stimson GV: The impact of HIV: Forcing the process of change. In: Strang J, Stimson GV (eds.): AIDS en drug misuse. London: Routledge, 1990, pp. 3-15, 34. Engelsman EL: Dutch policy on the management of drug related problems. British Journal of Addiction 1989; 84:211-218. 35. Erickson PG: A public health approach to demand reduction. In Alexander BK, Holborn PL (guest eds.): Alternatives to the war on drugs. Journal of Drug Issues 1990; 20(4): 563-576.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|