Summary, conclusions and recommendations

| Books - Female hard drug-users in crisis |

Drug Abuse

Summary, conclusions and recommendations

Several researchers have investigated the question of why women who use hard drugs and/or are involved in prostitution are so difficult to reach and why they keep away from treatment agencies (Van de Berg & Blom, 1987, Vanwesenbeeck et al. 1989, Keesmaat 1989). According to treatment organizations, women who use hard drugs are underrepresented (Van de Berg & Blom, 1987). The following explanations are given.

Van de Berg & Blom argue that the women are caught in a circle of prostitution and drugs and that they do not see any way out beyond their present way of life. The use they make of treatment organizations is aimed at sustaining their addiction, so they argue. The low-threshold treatment organizations have the function of providing them with methadone and time-out. Instead of motivating the women for a high-threshold treatment programme, the treatment organizations help the women who use drugs to maintain drug- use and prostitution. Van de Berg & Blom draw the conclusion that it is very hard for an outsider to break the circle of drugs and prostitution and that the only way to reach the women is to wait until they themselves are motivated to seek help. Their motivation for change is related to what they expect from life. Their expectations are influenced by: education; the experiences that influenced their path to addiction and prostitution; their position in the world of heroine prostitutes and their social contacts with family or friends (Van de Berg & Blom, 1987). In short: Van de Berg & Blom apply an individual perspective: change can only be expected, if the female drug-user wants to change.

Keesmaat (1989) & Vanwesenbeeck et al.(1989) have another explanation for the comparatively low numbers of few female drug-users in treatment. They point out that part of the group of women who use hard drugs and/or are involved in prostitution do not need help, because they are doing quite well. These women feel they are in control of their life and do not have social or psychological problems. They do not regard themselves as victims. Part of the group feels so demoralized that they do not expect that a social worker or a doctor can do anything for them. These women do not trust social workers and experience the traditional treatment organizations as so-called male bastions. According to Keesmaat(1989) and Vanwesenbeeck(1989), the absence of motivation is caused by a lack of trust in substance abuse programmes.

It is understandable then that the group formed by extremely problematic female drug-users could not be reached and treated by traditional substance abuse programmes. This group did not experience the traditional treatment programmes as sensitive to women's needs.

Contrary to traditional treatment programmes, the VKC provided a women-oriented services and a programme that excluded male drug-users. In a short time the VKC succeeded in reaching this group of formerly untreatable, highly problematic female drug-users, the so called 'hard core of heroine prostitutes'. It appeared that the female drug-users wanted to participate in treatment and in research. This made it possible to extent the knowledge about this almost unknown group. The goal of the present study was then as follows: to explore the characteristics of female hard drug-users, to understand female drug-use from a gender identity perspective, to describe the characteristics of female drug-users in treatment, to categorize their survival strategies, to analyze the relationship between childhood traumas, psychodiagnostic variables and treatment needs and finally to give some recommendations for treatment services. This study is divided into two parts. In the first part, the psychosocial background of women who use hard drugs is investigated along with the conceptual framework of female hard drug-use. Both angles are applied to the research group of 52 women who were treated at the Women Crisis Centre (in short: VKC).

The second part of this study consists of empirical research. The objective of the research was to investigate whether two sets of variables, childhood traumas and psychopathology, measured at baseline, were positively or negatively related to a speedy return to the VKC and/or the number of re-admissions within one year. In the Introduction the specific research questions have been described and the general methods of the present study has been presented.

Demographic characteristics of female drug-users

In chapter one, the general background of female hard drug-users is given. Approximately 7000 women in the Netherlands are addicted to hard drugs (Driessen, 1990). Approximately 10,000 women work as prostitutes in the city of Amsterdam. A small number of these women, fewer than 10 percent, are socalled 'heroine-prostitute'. Some 400 women belong to the hard core [i.e. their lives revolve around involvement in prostitution] of heroine prostitutes. The 52 research subjects are, apart from a few exceptions, part of this group of 'hard core heroine prostitutes'.

Comparing the psychosocial characteristics of the group of female drug-users that were admitted to the VKC with existing data from samples including female drug-users, the following becomes clear: on average, the group of research subjects are two years older and socially live in a far more isolated position than the female respondents of the sample by Korf & Hoogenhout (1990). Almost twice as many women from the research group (90%) are involved in prostitution as in the general sample.

How do women become drug-addicted prostitutes? Van de Berg & Blom (1987) distinguish five different paths to drugs and prostitution. They base their different paths on class distinction: they differentiate between lower class, middle class and upper class women. Also, they differentiate regarding the order of drugs and prostitution: their first two paths - heroine as downfall and heroine as trap - describe women who were first prostitutes and subsequently addicted; the other three paths, prostitution out of necessity (path three), prostitution as a slippery slope (path four) and heroine as rebellion (path five) describe women who were first addicted and later became prostitutes.

The paths show that in almost every case there is evidence of a narrowing of options: prolonged drug-use diminishes the prospects of gaining a job, of advancing education, of maintaining relationships outside the drugs scene or of taking care of children. The path distribution among the 56 women interviewed by Van de Berg & Blom (1987) shows that thirteen women followed path one, five women path two, fourteen women path three, seven women path four and seventeen women path five. In contrast to the women interviewed by Van de Berg & Blom (1987), most of the research subjects have a background of lower social class or of lower middle class and their dominant path to addiction and prostitution is called 'prostitution out of necessity'.

The research subjects are less educated than the women of the sample of Korf and Hoogenhout (1990). Contrary to the research sample of Korf and Hoogenhout (1990) the research subjects have no housing, are not medically insured and make less use of state benefit than the general sample.

Which drugs did women use? In 1987 drug-users generally preferred heroine, second came cocaine and third, cannabis (Korf & Hoogenhout, 1990). One third of the female drug-users used sleeping-tablets and tranquillizers. Almost three-quarters of the female drug-users used the substitute drug methadone (Korf & Hoogenhout, 1990). Almost all female drug-users are multiple drug-users. The dominant way to use drugs was to 'chinese' heroine or 'base' cocaine (techniques used to smoke drugs). In contrast to this data, the research subjects, although also multiple drug-users, use drugs predominantly (77% versus 29% of the general sample) intravenously.

It can be concluded that, given the fact that needle-sharing is a risk factor and research has shown that 30% of the intravenously drug-users is HIV-positive, the research subjects are more at risk from the AIDS virus than the women belonging to the general sample.

The conclusion can also be drawn that the extremely problematic female drug-users differ from the younger women of the general sample with regard to 'social position'. The women treated at the VKC live in a situation of much more social deprivation and isolation than other hard drug using women. They live, day and night on the street, socially they are isolated, they are not medical insured, have no physician and no state benefit.

Drugs make it possible to survive being an addict and a prostitute without housing and income. It is not a circle (Van de Berg & Blom, 1987) but a negative spiral of social isolation, prostitution and addiction that needs to be broken.

The social position of female drug-users is not only characterised by drugs, prostitution and material needs, but also by the legal context of drugs and prostitution. Female drugusers are doubly criminalized. Although Holland's drug policy is characterized by the dominance of the public health point of view, drugs remain illegal.

As yet, legalization is not feasible. Legalization of drugs means withdrawal from international conventions that outlaw the sale and use of drugs. Other objections concern the fear that legalization means spreading the use of hard drugs. Besides, in view of the important economic interests involved in the drugs trade (2,5 billion guilders), the option of legalization does not seem very feasible.

As yet, prostitution is a semi-legal activity. The Dutch Upper Chamber is discussing a proposal concerning abolition of the prohibition on prostitution. Among other things, the new regulation originally aimed to improve the position of prostitutes, but now the regulation's aim is to regulate prostitution and to prevent immigration of foreign prostitutes.

So, as far as their legal position is concerned, heroine prostitutes will remain doubly criminalized. The past years have shown a worsening in their social position, due to a more repressive climate. Recently the local authorities of the city of Amsterdam (1993) has made a distinction between streetwalkers and other prostitutes. Streetwalking remains on the wrong side of the law, stays forbidden, other kinds of prostitution in brothels will be allowed when the brothelholder has permission from the local authority.

A gender perspective on female drug-use

The social isolation of female drug-users and their socially oppressed position has probably influenced the attitude of scientific researchers. Ettore (1992) argues that until recently mental health professionals were guided by the idea that a woman who uses hard drugs is 'a fallen woman'. The field of 'women' and 'addiction' has, as a consequence, been a 'non-field'.

"The difficulties of introducing critical work on gender as a valid area of research in this field must not be underestimated" (Ettore, 1992, p.2).

She argues further that a feminist critique on drug does not exist. "Few, if any, feminist scholars have written about women and addictions".

The present study has tried to understand women who use hard drugs from a notion of gender and to apply an approach sensitive to the needs of women. After first summarizing the major models on addiction as background, Chapter Two goes on to initiate a tentative theory of female drug-use from a gender perspective. I have chosen a psychoanalytical conceptual framework that enables us to look at drug-use as a perverse strategy, as behaviour within a social context. In past decades, the concept of perversion traditionally described pathologies of sexuality, mostly pathologies of male sexuality. Kaplan (1991), a leading American psychoanalyst, has made a study of perversion as an expression of pathology of gender within the social context of patriarchal society. Her use of the concept of perversion is innovative, because she does not limit perversion to deviant, unusual or bizarre (male) sexual behaviour, as is usual (Freud, 1905). Instead, she extends the concept of perversion to female behaviour that enlists gender stereotypes in a way that deceives the onlooker about the unconscious meanings of the behaviours she or he is observing.

According to Kaplan, female perversions enlist social gender stereotypes as a way of surviving childhood traumas. From Kaplan's study I have selected two female perversions, 'Kleptomania' and the 'Horigkeitsscript', which are, in some ways, similar to drug-use. Just as drug-use is forbidden, it is forbidden to steal. Society views a woman that steals or uses drugs as a bad woman. So both women, the woman who steals and the woman who uses drugs, act out a deviant gender role, a 'bad woman script'. The so-called 'Horigkeitsscript' refers to extreme dependency on a man. A female drug-user is not only dependent on man, but also on drugs. She is not able to make her own choices, but is a victim of her own dependency.

Although Kaplan did not refer to female drug-use as a female perversion, I found it worthwhile to examine whether or not her theory could be applied to female drug-use as this would make it possible to generate a gender-perspective on addiction.

Considering the similarities in general characteristics of female perversion and female drug-use, drug-use might well be seen as a perversion and treated as such.

In Chapter Four, female drug-use as a female perversion was investigated at close hand. Two important types of gender identity conflicts occur in women's life and could be related to female drug-use: the conflict of whether or not to adapt to social gender stereotypes and the conflict of whether or not one is in control of one's own life. These gender identity conflicts could result in two main strategies: avoidance of unwanted feelings and need of control over one's own life with both an introvert and extravert variant. A combination of two survival strategies, 'anaesthesia' and 'submission', was the most frequently applied survival strategy (18 out of 52 research subjects). The 'anaesthesia' strategy followed second (15 out of 52 research subjects. 'Anaesthesia' refers to the numbing of unbearable, painful feelings caused by childhood traumas. 'Submission' is a combination of introverted energy in conjunction with subjection to some one else's control.

Less frequently, drugs are used to get a kick, to disrupt feelings of alienation (flash strategy) or to give a stage performance of a 'fallen' woman.

These results contradict the prevailing stereotypical social image of drug using women as sexually attractive, seductive women with a syringe in their hand, setting a shot, putting the moral code at defiance. It is more likely that a woman uses drugs because she does not want to feel painful emotions and has given up control of her own life.

Empirical research

Given the fact that research in this field is relatively new, much emphasis has been given in previous chapters to a research method that is explorative, qualitative and subjective while making use of the individual life-histories of women.

In addition, the empirical research part investigates the frequency, nature and predictive qualities of childhood traumas and the nature and predictive qualities of psychopathology present among the research subjects. Finally, the link between childhood traumas and psychopathology is examined.

The empirical research took place between June 1988 and August 1989, with a follow-up measurement in August 1990. The research subjects (n=52) are women who use hard drugs and are involved in prostitution. They were admitted between June 1988 and August 1989 to the VKC, because they were heavily addicted to hard drugs over a prolonged period and were in crisis.

Methods

Quite contrary to expectations, women who use hard drugs were keen to participate in interviews and did not object to filling out psychological questionnaires. They were curious, wanted to know more about themselves, wanted to gain an insight into the nature of their depression, their psychosomatic complaints and states of dissociation. The research subjects were highly cooperative and ready to share their often painful experiences. According to them, the way the data was gathered, was in sharp contrast to their former experiences in traditional substance-abuse treatment programmes. They now felt respected instead of humiliated. They felt encouraged by the accepting attitude, by the lack of pressure to abstain or detoxify.

Initially, a measurement had been planned at the date of discharge. The psychological questionnaires would again be distributed and the results of the questionnaires would be used as outcome criteria. The results would testify to the programme's value. However, this research design failed because some women felt frustrated at not being able to stay long in the Crisis Centre, and the Crisis Centre could not provide housing or financial aid. They had expected to stay longer until all their problems were solved. Some women were discouraged because the rules were strict and drug abuse or violence within the building led to discharge. Some research subjects left the Crisis Centre enraged, threatening never to come back.

This situation, women leaving the Centre in rage or in haste, made it impossible to systematically gather data at discharge. The data that was gathered could not be used because of its incompleteness.

It was not only the research subjects themselves who lacked the motivation to fill out the questionnaire on discharge, but also the Centre's staff. In contrast to the first phase of treatment, when the staff strongly supported the psychodiagnostic research, the last phase of treatment was focused on discharge and finding a good agency to refer to. If there was a vacancy at a treatment agency, the research subject was referred on to it, regardless of whether the psychological questionnaires were filled out or not.

Because of the above experiences we changed the outcome-measure to 'time between discharge and re-admission' and 'number of re-admissions'. The first criterium in particular, 'time between discharge and re-admission', proved very useful with regard to dividing the group into subgroups. This variable may provide a hint as to the treatment needs of a female drug-user, particularly if she returns to the VKC soon after discharge, makes clear that she is in need of further treatment and is not able to cope with her problems without the VKC's support. A rapid return to the VKC might indicate motivation for further treatment.

Results

Chapter Five is devoted to one particular part of the empirical research, namely that of childhood traumas. The frequency, number and predictive qualities of the childhood traumas was investigated. The traumas were listed on the basis of the data from the interviews. Not every trauma is one in the sense of DSM-III-R. Some events are an example of psychosocial stress events. For convenience sake I have applied the term 'trauma' both to 'real' childhood traumas and to psychosocial stress events.

The most frequent childhood traumas among research subjects (n=52) were: rape, physical abuse, parents' divorce and incest. Women who experienced 'physical abuse', 'rape' or 'placement in foster care' had significantly more traumatic events than women who did not experience the same traumatic events (Pearson chi-square test, p < 0,05). The mean number of traumatic events was three. From the eleven subjects who were placed in foster care, nine were raped and five had experienced incest. The relationship between 'foster care' and 'rape' was statistically significant.

The incidence of incest (33%) is twice as high as among the 'normal' female population (Draijer, 1990). The rate of incest found among the research subjects is similar to the rate found among female addicts and prostitutes and similar to the percentage of incest found among female psychiatric patients. In the present study, the incidence of physical abuse was one and a half times higher than the rate found by Rbmkens. It should however be noted that in the present study the incidence of physical abuse until the age of sixteen is measured, while Romkens lists the physical abuse of subjects of twelve and younger. The conclusion can be drawn that the research subjects are a multiplely traumatized group (they have experienced more childhood traumas than 'normal' women have), they have probably suffered as many or more childhood traumas than female drug-users of general samples, prostitutes in general, or female (ex psychiatric patients. On the specific trauma of 'incest' or 'rape' they do not score higher than other female psychiatric patients or other female drug-users, but it is still possible that multi-traumatization is higher within this group of female drug-users under treatment than in other groups. Further research is recommended with regard to the issue of frequency and the relative importance of multiple traumatization.

The childhood trauma data was statistically analyzed (HOMALS), but no statistically significant pattern or cluster of traumatic events was detected. This means that the coherence between childhood traumas is arbitrary. It is therefore necessary to list more traumatic events than sexual or physical abuse alone. Also with regard to treatment, the results of the present study do not justify a focus on 'incest' or 'physical abuse' as the only important childhood traumas.

On the basis of the literature (see Chapters Five and Six), it was expected that women who had experienced incest would return to the VKC sooner and go through more readmissions than women who did not experience such trauma. On the basis of the literature (see Chapter Six) it was also expected that women who had experienced combined traumas such as rape, incest and physical abuse would be an outstanding group with a significantly higher number of re-admissions than other women. Although a combination of traumatic events predicted the time between discharge and readmission, the individual childhood traumas did not.

The combination of traumatic events - `rape', `having an alcoholic parent', `the death of a sibling' and `belonging to a religious cult' - predicts speedy re-admission to the Crisis Centre quite well (r=0,85; p=0,00). 'Quarrelling between parents' predicts just the opposite: women stay away from the Crisis Centre for longer. In one way or another, all the childhood traumas responsible for a speedy return to the Crisis Centre involve some form of loss. 'Rape', 'an alcoholic parent', 'death of a sibling', 'parent committing incest with a sibling' and 'the family belonging to a religious cult' might confront the child with a feeling of helplessness, painful grief, sadness and lack of parental comfort.

Chapter Six is devoted to the kind of psychopathology that was found among the research subjects and the predictive qualities of the different psychological variables. The psychological self-observation questionnaires SCL-90 and BDI were used in order to investigate psychological/psychiatric complaints. On the BDI, female drugusers (n=52) scored much higher than women who had undergone psychiatric treatment and according to Cohen's formula the difference is large (0,80).

The differences between female drug-users and female psychiatric patients on the SCL-90 are minimal.

The group of re-admitted women (n=26) does not differ significantly from the group of non-re-admitted women (n-26) with regard to scores on BDI and SCL-90. The psychological questionnaires BDI and SCL-90 could not predict the number of days between discharge and re-admission, nor could they predict the number of re-admissions within one year.

All research subjects could be diagnosed as suffering from Psychoactive Substance Use Disorders. I have investigated the co-existing psychiatric pathology, applying three diagnostic categories of the DSM-III-R: depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and psychosis.

The DSM-III R diagnosis of depression NOS (almost 50%) occurred most frequently, followed by post-traumatic stress disorder (about 32 %). About 11% of the research subjects was diagnosed as suffering from psychosis. A few women (n=5) could not be diagnosed according to the axis I of the DSM-III-R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression predicted the period between discharge and re-admission to the Women Crisis Centre quite well, the post-traumatic stress disorder was of both diagnoses the more powerful predictor. Psychopathology did not predict the number of re-admissions.

Compared with international research the present study found the same amount of depressive disorders as in other study's, but twice as many anxiety disorders (in the present study only one specific kind of anxiety disorder was employed, the posttraumatic stress disorder).

As general conclusion it could be postulated that the range of psychopathology among the research subjects is within the range of psychopathology found among other drug-users. They frequently suffer from depression and it seems that depressions are more severe within this group of female hard drug-users than within the group of female psychiatric patients.

It can be concluded that the findings with regard to the occurrence of childhood traumas and psychopathology are in accordance with what is known in general about the childhood traumas and psychopathology of female drug-users, prostitutes and female psychiatric patients. It is remarkable that, in the present study, childhood traumas and psychopathology appear to be independent factors. More childhood traumas do not cause higher scores on the SCL-90 and BDI. There is almost no connection between individual diagnosis and childhood traumas.

It is difficult to draw any conclusions about the relation between social position, psychopathology and childhood traumas. The research subjects are in a worse social position than the female drug-users of the general sample (Korf & Hoogenhout, 1990), they also suffer from more psychopathology. It is possible that social position and psychopathology are slightly connected. The present study has not statistically analyzed this connection.

The question is whether or not social position could be explained by gender identity conflicts and the four problem solving strategies (Chapter Four). All strategies of female drug-users reflect a self-destructive attitude, a process of victimization and social stigmatization. It might be that a complex of factors, including childhood traumas, psychopathology and the consequences of social isolation, a position as female pariah and a self-destructive attitude based on gender identity conflicts, that all result in the social trap in which female hard drug-users are caught.

Recommendations

Drugs

The objection to the legalization of drugs is always that drug-use would spread and drug tourism increase. Although this may be the case, it is certainly not proven that putting a drug on a list of forbidden drugs will keep children and adolescents away from drugs. The consumption of Ecstasy after the addition of Ecstasy to list I of the Opium Act in 1988 shows the opposite: in the last years the use of Ecstasy has increased. Although legalizing hard drugs is not immediately feasible, it would be possible however, to introduce some experimental drug dispensing programmes for a certain group of drug using women, just like the dispensing programme in Widnes (Liverpool). The Amsterdam morphine dispensing programme (Derks, 1990) has provided a serious opportunity for extremely problematic drug-users to stabilize their lives and has not resulted in a free availability of morphine in the city, due to the strict conditions of the programme. One step further is a general drug dispensing programme for drug-using women, who use drugs as a survival strategy.

Prostitution

It is recommended that local authorities should aim to improve the position of prostitutes and only give licences to those brothel-owners who treat the prostitutes fairly and offer good working conditions.

The creation is recommended in Amsterdam of a free zone for streetwalkers, so streetwalkers can be treated as human beings instead of being hunted as beasts. A humanitarian approach towards prostitutes is in accordance with human rights regarding women's physical and mental integrity and expresses a respect for women's autonomy. Prohibition of prostitution wrongly criminalizes and stigmatizes female drug-users.

State benefit, medical insurance and housing

The group of female hard drug-users who were admitted to the VKC differed considerably from the female hard drug-users of the general sample with regard to their social position. Because many women have no housing, they cannot get state benefit and are not medically insured. If they are in need of treatment in a psychiatric hospital, referral is not possible, because they are not insured and have no housing. In order to break this chain of social expulsion, it is recommended that the various agencies for state benefit, housing and medical insurance be encouraged to work together in, for example, 'a crisis team' with well-defined responsibilities for improving the social circumstances of female hard drug-users and preventing their further social deterioration.

It is also recommended that cheap 'boarding houses' be created for female hard drug-users and that they be given responsibility and support for the running of these boarding houses.

It is also recommended that a 'hostel' be founded: a safe bed, bath and breakfast for female hard drug-users.

Children

Half of all the female hard drug-users have children. Few of them are able to take care of their children, many of them have no contact with them. A great deal of the research subjects suffered as a result of the loss of contact with their children. They welcomed a new pregnancy as a second chance to become a good mother. The few women who

cared for their children were afraid that in-patient treatment would mean that the children would be put under legal protection and into foster care. Amsterdam has one centre for mothers with small children, Beth Palet. Women who are addicted to drugs could be referred to this centre. Some research subjects were referred to this centre after

crisis intervention. Although they were glad that they could stay there with their baby, they regretted that they were seen only as mothers and not as drug-using women who were in need of treatment. These women failed and left the centre. Another possibility in Amsterdam is a day care facility for addicted parents with children under the age of five. Although these facilities are a step in the right direction, it would be better if conditions could be created where mothers could get treatment and remain in contact with their children.

Education and work

In the present study it is shown that female drug-users have little schooling and that their social background is lower class or lower middle class. It is recommended that special programmes for female hard drug-users be set up to stimulate education, work and social integration. Although the present rehabilitation programmes do sometimes have special women's groups, there is no special rehabilitation programme focused on women and sensitive to women's needs. Most of the research subjects have a history of prostitution. They say that they need to talk about their former experiences, because sometimes, when going to school or when starting work they re-experience some events connected with prostitution. In mixed programmes they do not dare talk about prostitution. In class they are afraid that other people may find out they are a prostitute. In mixed rehabilitation programmes they are afraid of men and male teachers and may drop-out.

Treatment programmes

After admission to the Women's Crisis Centre the research subject was asked: what do you think the Women Crisis Centre can do for you? The answer categories consisted of five possible answers: next to nothing; provide some rest; getting support, sorting things out; to get over the crisis; other things...

The research subject was also asked: What do you expect you can do for yourself? There were three possible answers: next to nothing; to stick to agreements; other... Most women wanted to get some rest, sort things out (among other things: finance, housing and relationships), come out of crisis and make important decisions about their future.

Their first need is to get assistance for solving practical and material problems such as:

- getting state benefit

- making a list of other possible sources of income, such as child or family allowance or individual rent subsidy

- purging debts

- getting a National Health Service registration

- applying for a certificate of urgency to get a house

- listing judicial problems and possibly jail sentences

- beginning a divorce or contacting child protection in order to see the children

The research subjects did expect that they could keep agreements about solving material problems and sometimes they wanted to get better.

For many women who use hard drugs, addiction is not the problem, addiction is the solution to their problems. Chapter Two contains an explanation of how drug-use solves women's gender problems and childhood traumas.

The dominant view on substance-abuse ignores women's social context, their childhood traumas, gender identity problems and their former experience as a prostitute. After the assistance in material problems many research subjects require assistance in solving their psychological problems including their drug-use. For further help I recommend that first of all the contra-indications of the so-called regular mental health care institutions must be reviewed.

The most important recommendation of this study concerning treatment is that treatment of childhood traumas, treatment of gender identity problems and treatment of migrant problems are essential elements in the treatment of women who use drugs.

The treatment of female hard drug-users could possibly be integrated into programmes that are now being developed for the mental health care (NVAGG, 1993). 'Mental health care in programmes' is a response to the demand that mental health care and cure should provide programmes in response to the market. This development must be seen in the context of the reorganization of Dutch Mental Health Care System.

The future programmes will not be based on the diverse organizations, but on the different functions of mental health care. The NVAGG (1993) has described the following functions: indication and advice; treatment; guidance; in-patient nursing and care; long stay treatment and prevention. For each target group a programme based on the above functions could be developed. The following female target groups might be distincted: female migrants, including migrant [hard drug-using] prostitutes, elder women, chronically psychiatric women, traumatized women, mothers with children, women who use substances and female minors. For each of this targetgroups a circuit of care and cure might be developed, including the functions of indication and advice, treatment, guidance, nursing and care, long stay treatment and prevention.

Female drug-users could in the future be referred to the programme for addicted women, but also to other women's programmes according to their treatment need and diagnosis.

On the basis of the data of the present study (n=52) the target group of extremely problematic female hard drug-users could be subdivided into the following segments: - female migrants (40%)

- chronic psychiatric patients with the diagnosis 'psychosis' (10%)

- sexually and/or physically traumatized women (incest 33%, rape 42%; physical abuse 38%)

- mothers with children (50%)

- women with the problem of addiction to substances, food, gambling or tranquillizers (100%)

Because female drug-users differ in their treatment needs, gender identity problems, childhood traumas, coping strategies, social position and their diagnosis and prognosis, it deserves recommendation that they are referred to a programme tailored to their needs and not only to the programme for addicted women.

The diverse programmes are all women-oriented and provide treatment for gender identity problems, the diverse survival strategies and individual needs. The different programmes are not detailed yet, but I will give some indication of the special activities of the diverse programmes. The programme for mothers with children will provide part-time treatment, special facilities for children and training of the mother as parent. The programme for chronic female psychiatric patients will provide long-stay programmes for women and special rehabilitative training. The treatment of traumatized women will focus on out-patient treatment at the 'RIAGG'. Female drugusers who wish to cease drug-use will be referred to the women's programme for substance use which will be provided by the substance-abuse treatment agencies.

It is possible that a woman might be referred from one programme to another, according to her treatment plan. For example, she might start with detoxification in the women's programme for substance abuse and subsequently participate in the programme for traumatized women. Another example: a chronically psychotic woman might participate in the programme for chronic patients and stay in a "long-stay centre", also participating in a group for addicted women in the programme for substance use. Further research

Right from its very beginnings in 1987, the Women Crisis Centre has carried out follow-up research. Three months after discharge from the Women Crisis Centre the agency who had the client in treatment was asked about the well-being of the client. The following questions were asked: is the woman still in treatment? How is she doing? How many times a week or a month does she visit the treatment agency? Does the treatment policy of the agency match that of the Women Crisis Centre?

After the follow-up measurement in August 1989 we heard that one woman who had not been re-admitted within a year had been murdered in 1989 by her boyfriend. Her case is still included in the category 'non-re-admitted women'. Her data did not have to be eliminated, because she did not belong to the group of women upon whom the predictor analysis was based.

The follow-up measurement in August 1990 showed that fifteen women out of the 26 not re-admitted women had improved. From the ten women who were treated as out-patients, seven had improved. Eight women were still in in-patient treatment and had improved.

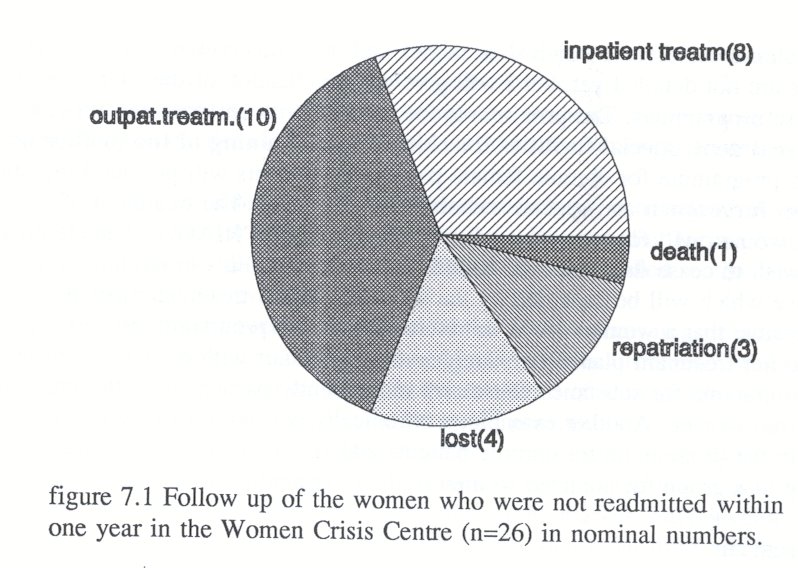

Seven women were out of reach of Dutch treatment services, three had gone to Germany or Austria, four women were not in contact with treatment agencies. Figure 7.1 shows the follow-up:

Follow-up in august 1991

In august 1991 it appeared that two women from the re-admitted group had died, one woman died of an overdose, the other woman of a brain haemorrhage.

Because the material gathered at base-line is almost complete, it deserves recommendation that a follow-up study be organised on the research subjects of the present study to investigate the survival-rate of the research subjects, their drug-use and social situation. Investigation after a number of years might give some insight into the variables that, in the long run, are crucial in the lives of female drug-users.

Also, some single-case studies might be done to gain insight into the development of certain variables, such as social position, gender-identity, addiction, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, prostitution, multiple traumatization and social and family relationships. The interviews then could be videotaped and appraised by independent observers. With regard to the next research project it deserves recommendation that a supervisory committee, including two female drug-users, be installed in order to interpret the data, to draw conclusions and to guarantee the representativity of data.

Further it merits consideration to design a screening list to detect depression and posttraumatic stress disorders, because these disorders predict a speedy return to the Women's Crisis Centre and these women probably are able to profit from treatment when they are referred to other treatment agencies. Women with the diagnosis 'psychosis' also deserve early detection, because they probably profit more from an approach based on providing structure, support and the opportunity to form a relationship of attachment to one or two members of the staff. In contrast to the women with the diagnosis of 'depression' or 'post-traumatic stress disorder' these women generally will not profit from a quick referral, because first of all a relationship based on trust is needed. Probably a form of 'case-management' is indicated.

Investigation is recommended in a following study of the family background of female drug-users, because it is remarkable that the most powerful predictors are linked to the situation at home. 'Quarrelling between parents' as most powerful predictor variable predicts a longer stay outside the Women's Crisis Centre, 'member of a religious cult' is second in place to predict a quick return to the Crisis Centre. It would be advisable to compare the family background of the female drug-users with women of 'Blijf van mijn Lijf' homes or with female psychiatric patients.

It is recommended that a certain part of research funds be reserved to stimulate research on women and addiction and to evaluate the above women programmes.

| Next > |

|---|