Chapter three Female drug-users in treatment

| Books - Female hard drug-users in crisis |

Drug Abuse

Chapter three Female drug-users in treatment

3.1 Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to study the characteristics of the sort of women who undergo treatment at the VKC. I shall compare this group with what is known of female drug-users in general as described in chapter one. In chapter one it was said that the average age of female hard drug-users is 28 years; in more than forty percent of all cases the women are of foreign origin; they generally belong to lower class or lower middle class, in half of the cases the mother is a housewife; female hard drug-users tend to have little schooling; they live with others; half of them have children; they have a physician, housing and a weekly income of 711 guilders, spending an average of 820 guilders a week; in more than half of the cases the women's main source of income is prostitution (Korf & Hoogenhout, 1990).

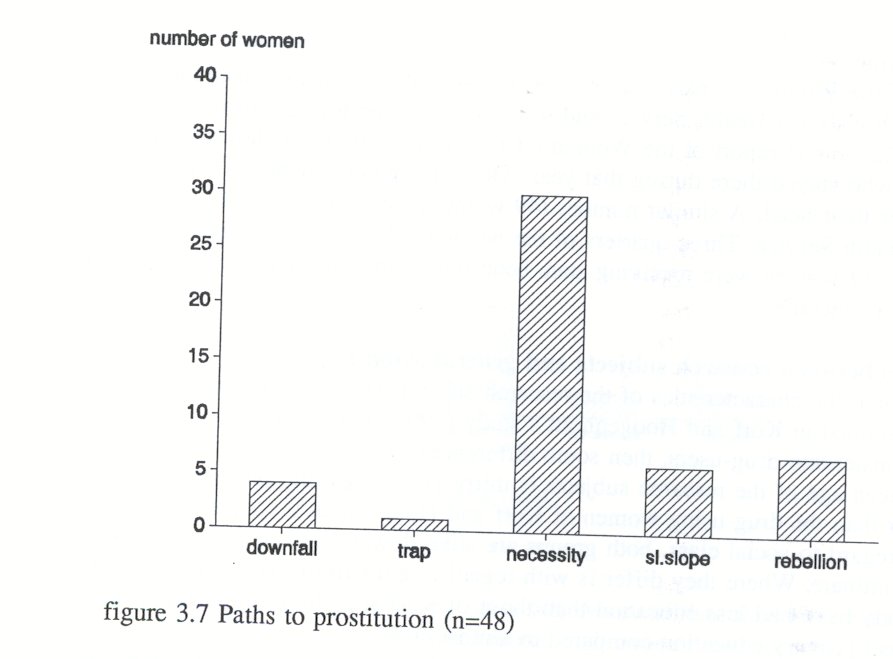

It was also shown in chapter one that the following five paths led to addiction and prostitution: heroine as downfall and heroine as trap (both paths apply to women who were already involved in prostitution and subsequently became addicted); prostitution

out of necessity; prostitution as a slippery slope and prostitution out of rebellion (these paths apply to women who were first addicted and only later turned to prostitution). This data, showing as it does a picture of women who are living on the fringes of society and whose lives might turn into a negative spiral, are compared to data of female hard drug-users whose lives are in crisis and who find themselves unable to go on. This comparison should enable us to gain insight into the general background and the social position of the female hard drug-users in crisis who are admitted to the VKC. Later chapters will develop particular themes, such as psychopathology and childhood traumas.

Before supplying the demographic data of this particular group of women and their paths to addiction, I will first explain the methods of data collection, the background of the VKC and the way the research subjects were referred to the VKC.

3.2 Methods

Data collection

All clients who were admitted in the Women's Crisis Centre during the period June 1988 to August 1989 were asked to participate as research subjects. One person refused. Some of them stayed in the Centre for only a few hours, so that it was not possible to collect any data. The remaining 52 subjects gave permission (informed consent) for their data to be used for research.

The collection of data started in June 1988. On the first day of their stay in the VKC, clients were asked by a staff member general questions about their age, source of income, marital status, children, previous therapy and physician. On the next day, the clients were interviewed by one of the three psychologists about their crisis, its background, problem-solving strategies and related problems (the semi-structured interview is featured in appendix two). Almost all the participants of this study were using methadone at the time of the interview.

The data, collected on admission, was divided into categories, such as age, cultural background and crisis situation.

Setting

The Women's Crisis Centre provides a short, in-patient crisis intervention treatment programme for six women at a time. The length of stay is limited to three months. In order to be admitted to the programme, a woman has to meet the following two criteria:

- she has to be severely addicted to drugs

- she has to be in crisis

The first criterion means that a woman who has been addicted for only a few months will be referred to another agency for out-patient treatment. Very young women of thirteen or fourteen years old are also referred to other agencies. The second criterion means that admission must be the only possible solution to the crisis: a woman is unable to solve her problems on her own or with help from family or friends.

Female drug-users who are not in possession of a Dutch residence permit are not admitted to the Crisis Centre unless it can be demonstrated that there are exceptional humanitarian or medical reasons in favour of doing so. In such a case, the treatment goal is repatriation. Admission is not possible if a female drug-user requires more medical or psychiatric care than the Centre is able to provide.

Referral to the VKC

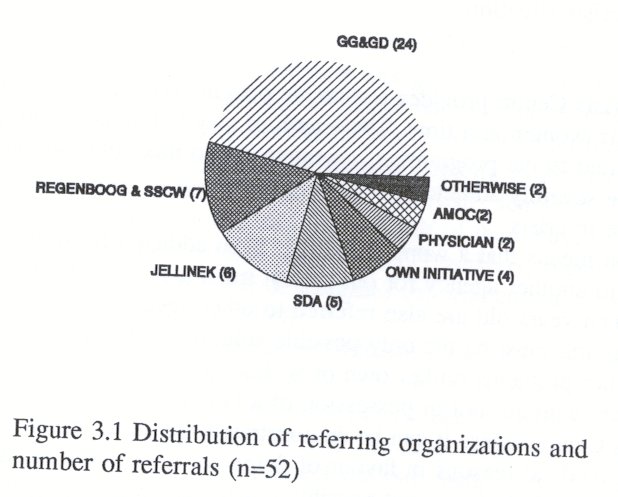

Almost half of the group (24 women) were referred to the Women's Crisis Centre by the Municipal Mental Health Service (GG&GD). The GG&GD holds surgery hours for prostitutes. If a prostitute is seriously ill or in crisis, the GG&GD calls the Crisis Centre and refers or brings her as soon as there is a vacancy.

One Christian organization, the 'Regenboog' Foundation which does outreach work at night among the heroine prostitutes also brings the women to the Centre if they are in crisis, exhausted and depressed. Together with another low threshold organization called 'Street Corner Work', The 'Regenboog' referred a total of seven women.

The Jellinek Centre, which can more accurately be termed a high-threshold centre for in-patient and out-patient treatment services for substance abusers also refers clients to the Women's crisis centre, if, for example, a woman is in crisis but cannot find the motivation to undergo detoxification or other treatment.

The 'Stichting Drugshulpverlening Amsterdam (in short: SDA) referred 5 women. The SDA has some women in treatment on an out-patient basis and offers counselling services, provides methadone and sometimes state benefit. Women who are in the care of the SDA can also eat at a canteen and sleep at night at the 'Nachtopvang' of the SDA (a kind of bed and breakfast for homeless drug-users). If the 'Nachtopvang' is not able to accommodate the women, for example if they are too ill or too mentally unstable, then the 'Nachtopvang' refers them to the Women's Crisis Centre.

Other referring agencies include the woman's own doctor and a German organization for the repatriation of German drug-users (Amoc).

Figure 3.1 shows the distribution of referring agencies and the number of women they referred. Four women had heard of the Crisis Centre and came on their own initiative.

The referring agencies were asked what their expectations were of the Crisis Centre. Most of them expected that the woman being referred was not motivated for help, and was therefore only in need of time-out.

3.3 Demographic characteristics Age

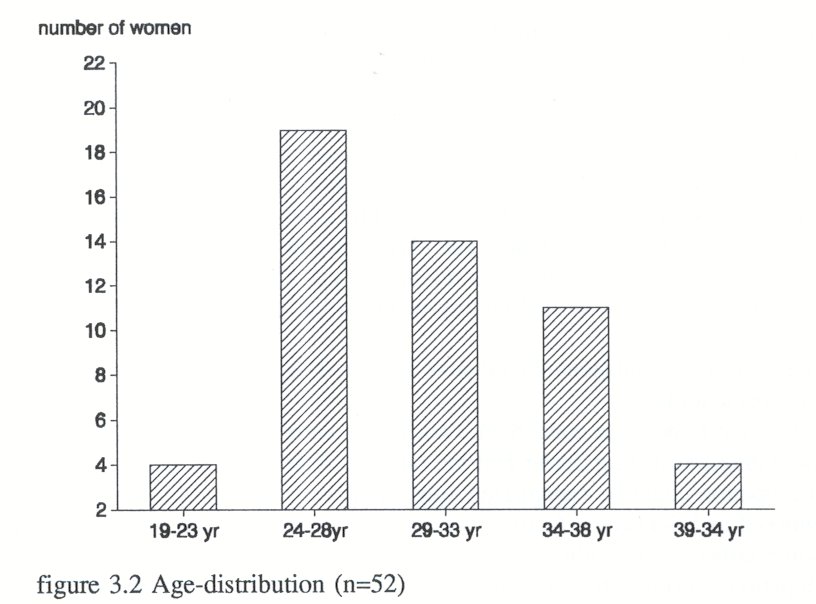

The mean age of the research subjects (n=52) is thirty (sd=4,9). There is an age peak between 24 and 28. Figure 3.2 shows the age-distribution.

Cultural origin

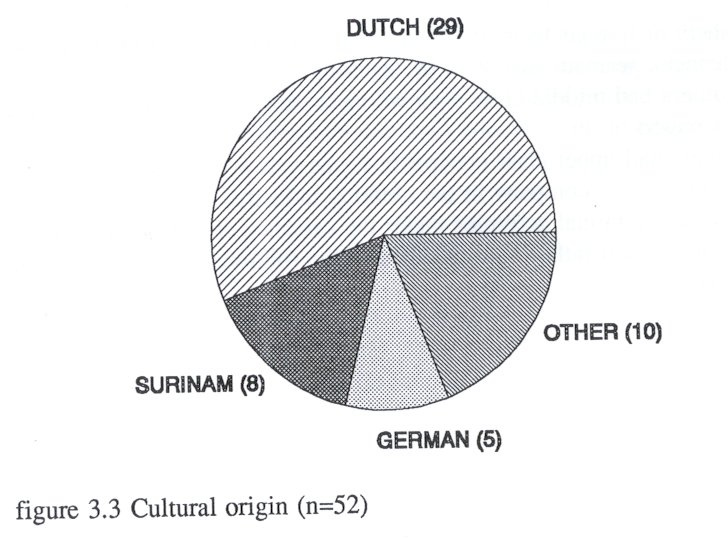

Figure 3.3 shows that the majority of the women are of Dutch origin, followed by those of Surinam origin and after that the group of German origin

Social class of parents, environment and education

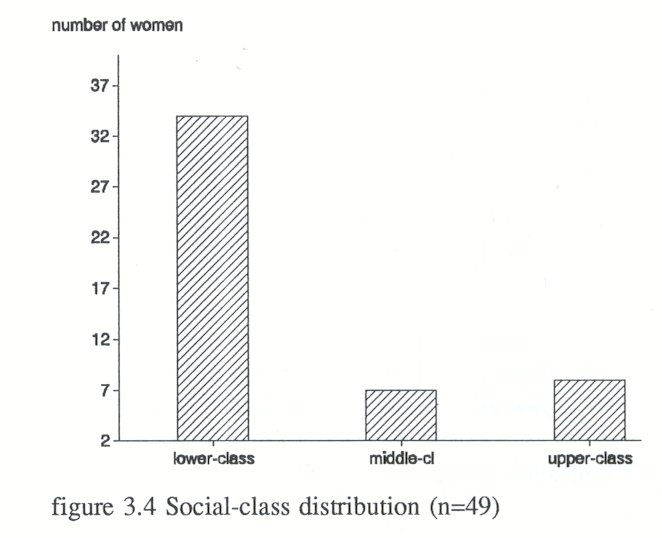

The classification is based upon common Dutch classification of social classes. The social classification includes three levels: upper class, middle class and lower and lower-middle class.

Upper class is Class A. Upper class refers to company directors, top civil servants, doctors and professionals such as writers and musicians.

Middle class is Classes B1 and B2. The middle class includes directors of small and medium sized businesses, teachers and civil servants.

Lower class and lower middle-class refers to social Classes C and D, and includes those with small businesses, skilled factory-workers, the unemployed and those on state benefit.

Of the 52 research subjects, 49 subjects answered the question about their father's or mother's occupation.

As far as the fathers are concerned, two fathers earned a living from criminal activities; one worked as a drug dealer and the other as a pimp. In 20 of the cases, the father's occupation could be categorized either as lower class or as lower middle-class. Fathers worked as bricklayers, factory workers, taxi drivers, garage workers or salesclerks. Some fathers were without work. In eight of the cases, the fathers had a middleclass occupation, working, for example, as teachers, managers, political journalists or civil servants.

Some fathers (4) had upper-class occupations, working, for example, as bank manager, architect or professional engineer. Two fathers had creative jobs: one was an inventor and the other was a musician.

As far as the mothers' occupations are concerned, many research subjects (17) responded that their mother worked as a housewife or else that she had no job. In order to establish if they were lower class or middle-class housewives, I looked at the occupation of the mother's husband or partner and found that four house-wives had partners whose jobs would place them in the middle-class bracket. Two research subjects said that their mother was or had been a prostitute. One mother was married to an engineer.

The mothers of five subjects had lower or lower middle-class occupations. They worked as cleaners, seamstresses or in the catering industry.

Eight mothers had middle-class occupations as nurses, civil servants, secretaries, teachers or managers.

Two mothers had upper-class occupations; one was a psychiatrist and the other manager and owner of a company in the clothing industry.

I have classed criminal activities under the category of lower-class. Data comparing mother's and father's job resulted in the following social class distribution (see figure 3.4)

Financial situation

27 of the 52 research subjects answered the question about the financial situation in their family of origin. Eight subjects described their family as poor; many of them (19) said that as a child they had had enough money and some of them termed their family rich or very rich.

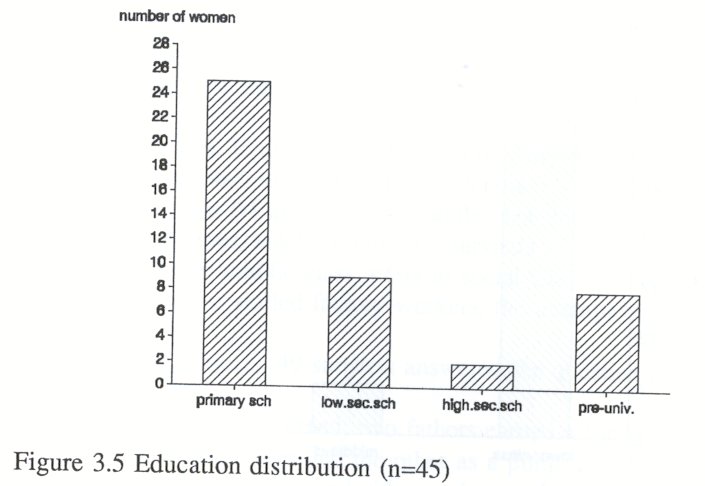

Education

45 of the 52 research subjects answered the question on education. Figure 3.5 shows the distribution of education. One research subject had never gone to school. 25 research subjects had had primary school and/or domestic science school or lower vocational education. Nine research subjects had lower general secondary education, two of them had gone to higher general secondary education and eight of them had a pre-university education, including one women who had been to a teacher training college.

Education seems to be a weak point in the background of female hard drug-users; half of the women had only had lower (vocational) education or no education at all.

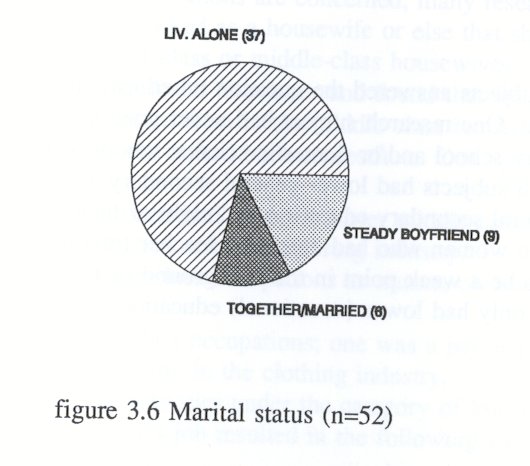

Marital status

Many research subjects lived alone (37 of n=52). Many of them had had relationships in the past. Of the 37 subjects who lived alone, eight women had formerly been married or had been living together with a man. Six of them were married or lived with a man or a woman. Nine women had a steady relationship or a male friend (see figure 3.6).

Children

Almost half of the women (25) had one or more children. Fourteen women had no contact with their children, eleven women saw their offspring sporadically or only had contact with them by telephone

Social position

The staff of the Women's Crisis Centre collected data about housing, insurance cover by the Dutch National Health Service and sources of income for administrative purposes. The annual report of the Women's Crisis Centre for 1989 shows the data of 68 women who stayed there during that year. Three-quarters of them (53 women) had no roof over their head. A similar number (49 women) was not covered by the Dutch National Health Service. Three quarters of the women (51) earned money from prostitution, 14 women were receiving state benefit and three women gave drug dealing as a source of income.

Differences between research subjects and general sample

If we compare the characteristics of the research subjects (n=52) with the data from the sample examined in Korf and Hoogenhout's study (1990) among more than two hundred Amsterdam drug-users, then some differences can be noted.

The mean age of the research subjects is thirty years; they are, on average, two years older than the drug-using women of Korf and Hoogenhout's sample.

With regard to social class, both groups are alike: lower class and lower middleclass predominate. Where they differ is with regard to education; the subjects of the present study have had less education than those of Korf and Hoogenhout (almost 50% has only had primary education compared to almost 40%).

As far as social circumstances are concerned, the groups differ greatly. Korf and Hoogenhout's female research subjects have housing arrangements and they often share housing with a boyfriend. Three-quarters of the research subjects in the present study have no roof over their heads. Twice as many of Korf and Hoogenhout's women received state benefit as did the women in the present study. More women in the present study are prostitutes (90%) than in the general sample (50%).

The conclusion that can be drawn is that the women who use hard drugs and come for treatment to the VKC live in situations of much more social deprivation (no housing, no doctor, not medically insured, no state benefit) and much more social isolation than the group of women who use hard drugs in general.

3.4 Paths to addiction and prostitution

Introduction

Many of the women (48 of 52) are involved in prostitution. In Chapter One I described the paths to prostitution (Van de Berg & Blom, 1987). The results of the present study show that Path Three, prostitution out of necessity, which is chosen by thirty lower class women, is the most common route. The next path is path 5, prostitution out of rebellion, a route chosen by seven upper class women. Path 4, prostitution as a slippery slope, a route similar to path three, but then chosen by six middle-class women, comes third. Four lower-class women started working as prostitutes and subsequently became addicted (path 1, heroine as downfall). One middle-class women worked first as a prostitute and later became addicted (path 2, heroine as trap). Figure 3.7 shows the path distribution.

Each path will be illustrated by a case-history.

Path one Heroine as downfall

Path 1 describes lower-class women who chose prostitution as a profession. These women often grew up with women who were professionally involved in prostitution. For these women, becoming addicted means failure as a professional prostitute.

Saskia's story

Saskia died in 1989 from the after-effects of physical abuse by her boyfriend. After her death, her boyfriend committed suicide. She left a teen-age daughter of eighteen.

In brief, Saskia's life-history is as follows. She was the eldest of 10 children. Until the age of six she was happy, as she was in the care of her grandmother. At this point, her mother wanted her to live with her, and from then on her life changed dramatically: she was beaten by both her father and her mother and was raped by her father when she was ten years old.

She broke free when she was sixteen and started earning a living by prostitution. By the time she was eighteen she had started taking drugs. When she was 19 she met her boyfriend. He physically abused her and forced her to continue with her prostitution.

Before her death, Saskia had one stay at the VKC after having been beaten up by her boyfriend. She was not interested in therapy and returned to him after a short period.

Path two Heroine as trap

Path two is chosen by middle-class women who enter prostitution in order to have fun. The women are generally independent and they use the money they earn from prostitution for clothes, parties and cocaine. They are unaware that they risk becoming addicted. It is as if they are suddenly caught in a trap: their education is unfinished, they have no work experience and they cannot choose to opt out, do 'normal' work and stop drug-use. Path two could only be applied to one of the research subjects. However, her case-history does not show that she became involved in prostitution out of pleasure. In her case, prostitution was necessary because she needed some means of support after having ran away from home. Nevertheless, I have categorized her case under path two, because she answers the criteria: she is of middle-class origin and her involvement in prostitution preceded her drug addiction.

Helen's story

Helen, a Dutch woman of 27, was admitted at the VKC after she had heard that she was HIV-positive.

Her background is as follows. Helen's father was a teacher, her mother, a chronic psychiatric patient who was placed in a mental institution when Helen was three years old. Her mother developed schizophrenia following the death of Helen's little sister. Helen still visits her mother in the mental hospital once a month.

After her father's death, Helen, then eleven years old, was placed in foster care. At the age of fifteen, she reported to people at school that her foster-father was sexually abusing her. Nobody would believe her. She felt ashamed and ran away. Because she needed money, she turned to prostitution. After meeting a drug-addicted boyfriend she became addicted. Her boyfriend physically abuses her.

Path three Prostitution out of necessity

Path three, the most common route to addiction and prostitution, is referred to by Van de Berg & Blom (1987) as 'prostitution out of necessity' and evokes the picture of women who have fallen into a trap. Their life starts as a trap, as a narrowing down of opportunities. Some of them are placed in foster care when they are four years old or younger, some of them are raped or beaten up, many of them are neglected and have experienced poor parenting. They all come from working-class backgrounds and have only primary school and a few years of advanced education.

Shanti

Shanti, a Dutch woman of 34, is referred to the Crisis Centre by a doctor because she is psychotic. She is homeless, no longer looks after herself and requires medication. She uses half a gramme of heroine and half a gramme of cocaine a day. She started using drugs when she was eighteen. Her story is that her boyfriend laced her food with drugs.

Shanti has a history of psychiatric treatment, including a spell as an in-patient at a psychiatric hospital, though she refuses to talk about this because the experience was too horrible for words. She spent two years there.

The story of Shand's background reflects her inner confusion. Her father, she claims, is of noble birth and Shanti says she dearly loves him. He was a sailor and bought her in France when she was four years old. Though her father placed her on a

pedestal, Shanti also felt imprisoned. He is now a garage-owner and is the only one Shanti can trust.

According to Shanti, her mother is her father's exact opposite. She herself is somewhere between the two. Shanti says that her mother has committed incest with Shand's brothers. But actually, she says, they are not her brothers: one is from another man and one is adopted. Shanti is afraid of her mother and her brothers, because, according to her, they tried to kill her because she knew about the incest. Shanti says that they had closed the doors and windows and beaten her up.

Shanti was married between the ages of eighteen and twenty-six. According to her, her husband was a mean person, who physically abused her, forced her into prostitution and forced her to take drugs.

Shanti has been to jail for stealing garments from shop-window dummies. The clothes on the dummies were not attached to a security-device, so she could steal them without getting caught.

She has had drug-free periods. But, she says, it is a pleasure for her whenever she is addicted again. When she is 'clean', she suffers from 'clean-freaken', as she calls her religious delusions. Once, when she was clean, she predicted that a girlfriend of hers would be raped in one and a half hours. When she was proved right she immediately went back to using drugs.

Nowadays her father and mother are divorced and Shanti stays in contact with both of them. She lives on the streets and switches from one treatment services centre to another.

Path four Prostitution as a slippery slope

This path resembles the path mentioned above, but with one important difference: the women of path four have had more opportunities in life. They have grown up in middle-class surroundings. Six women took path four.

Donna

Donna, a 32 year old woman from Surinam with a four year old son, was referred to the Crisis Centre because she has chronically been living in crisis since she left her husband one and a half years ago. Her crisis situation was aggravated when she was put in jail because of blackmail. She has lost weight and is exhausted.

She started using drugs when she was nineteen. Her boyfriend locked her up, beat her and forced her to use drugs. She has been addicted to heroine, cocaine and alcohol since the age of 21. She uses drugs intravenously.

Speaking about her family background, Donna says that she has never known any stability or security. Her mother, who worked as a teacher, had one boyfriend after another. Donna's father, her mother's second husband, was succeeded by fivestepfathers. She has two brothers and five sisters. Donna is the second child. She remembers fights between her father and her mother; once, her mother had beaten up her father so badly that he had to go to hospital.

After the divorce, Donna's father's became very indifferent towards her. She has not seen him since the age of fifteen.

When Donna describes her relationship with her mother she always starts to cry. Her mother is a very severe woman who physically abused her children, sometimes with sadistic punishments: once she smeared pepper in Donna's face.

Her mother always said to Donna, "You are my dearest child, but also my ugliest." Or "You are as ugly as a monkey". Donna thinks that her mother was jealous of her daughters. Her mother was only interested in material goods. Donna cries because she longs for her mother's love. Positive about her mother was that she taught her children to behave properly and hygienically, and that she protected them against men.

Donna left home at the age of fifteen. She ran away, went to her grandmother's and her grandmother send her to an aunt. She worked for a year and a half in a hospital in Paramaribo.

Meanwhile, her mother went to the Netherlands and asked her to come and join her. Donna left for the Netherlands and thought everything would be ahight with her mother. But when she arrived in Holland, her mother's physical abuse started all over again.

Before she was 23, Donna had had several boyfriends, three miscarriages and one abortion. At 26, she got married. She was her husband's eighth marriage. Before her marriage, she had been warned by the seventh wife that her husband-to-be was not a nice man. But she hoped she could change him. After getting married, her husband physically abused her, but because she was pregnant, she stayed with him. Moreover, she wanted to spare her child an endless string of stepfathers.

During the first years of her marriage Donna stayed clean, but relapsed after her husband had physically abused her and when she felt she could no longer care for her child. She ran away. On her return, she found that her husband had placed their child in foster care and so she gave up. She deeply felt that she had failed as a mother.

When asked about her motives and reasons for continuing her addiction, Donna refers to her mother's physical abuse, her longing for the love of a mother and a father, her depressive reaction after the loss of her son and her distrust towards other people. She does not think she is able to trust anybody. She has developed a general anxiety of prostitution and snails. Because of her fear of prostitution, she prefers stealing. According to Donna, her fear of snails is related to her Surinam background. Donna's case-history shows many parallels with the above mentioned cases of path three. There is mention of childhood physical abuse, absence of a father, running away at fifteen, repetition of physical abuse in her relationship with partners and being forced into the use of hard drugs. She earns money through prostitutioin out of necessity, trying to talk her clients into satisfaction and avoiding physical sexual contact.

The differences are that Donna is relatively well-educated. She finished advanced primary education and took a medical secretarial course. She has worked as a medical secretary. Donna shows some insight into her inner conflicts; she is aware that she still is hoping to be loved by her mother and father and also of how hopeless this longing is. She is able to put her feelings, thoughts and fantasies into words. But still, this does not mean she is able to cope with her situation. She would like to give up drugs, but every time she tries, she relapses.

Path five Addiction and prostitution out of rebellion

Seven women took path five, the upper-class women's path. According to Van der Berg & Blom (1987) these women developed an addiction because they wanted to rebel against their environment, traditions, mother and father. In a certain way this is true. But they are also rebelling against an unhappy childhood and from this point of view their drug use resembles that of the women in path three and four.

It is remarkable that only one woman on this path is of Dutch origin. The other six women are of foreign origin: two are from Surinam, one is Italian, one German-Italian and two Austrian.

Laura

Laura, a 25 year old woman from Surinam, was admitted to the Crisis Centre after giving birth to a baby that was stillborn. She has an one year old son who is cared for by her sister-in-law.

Laura's father was a writer, her mother, a housewife. Laura has nine brothers and sisters of whom she is one of the youngest. She adored her father and because she was one of the youngest, he spoiled her very much. He has never done anything wrong. Her mother is a gentle person, though a little bit weak, always seeming to choose the easy way out. Laura's father died when she was six years old.

Laura's education consists of three years Higher General Secondary Education and vocational training.

After her father's death, her life changed dramatically. Her mother got a boyfriend and was physically abused by him. Her mother ended in a wheelchair, lives in a nursing home and is becoming an alcoholic. Laura's elder sister took over responsibility for

Laura and placed her, at the age of sixteen, in a supervised rooming project. It was there that she met her addicted boyfriend, who supplied her with drugs.

After she became addicted, a girlfriend introduced her to prostitution. She developed into a classy prostitute with her own fixed clientele, but she still loathes prostitution and is only able to do it by suppressing her feelings.

She had a personal relationship with a former client, the father of her son. He wanted her to stop taking drugs and to stop working as a prostitute. When she was unable to stop her drug-use, he left her. Shortly afterwards, she found a new boyfriend and got pregnant again. This was the child that was stillborn.

According to Laura, she cannot stop using drugs because this makes the memories about her mother become too painful. Her drug-use enables her to forget her worries about her mother.

Comparison with the study by Berg & van der Blom

The data gained from the research subjects can be compared to the data published by Berg & Van der Blom (1987). Van de Berg & Blom interviewed 65 heroine prostitutes, both male and female. They excluded the data from nine interviews, in some cases because the heroine prostitute was male, in others because the quality of the audiotape was poor. The average age of the 65 people interviewed was 22. According to the researchers, their sample is not quite representative: they estimate that more middle-class and upper-class women were prepared to give an interview, and that single women were over-represented in their sample because married women or women with a steady boyfriend were afraid to co-operate. The path distribution among the 56 women interviewed by Van de Berg & Blom (1987) shows that 13 women followed path one, five women path two, 14 women path three, seven women path four and 17 women path five.

The results of the present study are in marked contrast to those of Van der Berg & Blom. Path 3 is the predominant route (30 women), followed by path 5 (7 women). It seems more and more obvious that, when compared to the group of heroine prostitutes as a whole, our research subjects seem to belong to the category with fewer opportunities than the 'average' woman who uses hard drugs. They have a socioeconomic background of lower social class, they have little schooling and they are involved in prostitution out of necessity.

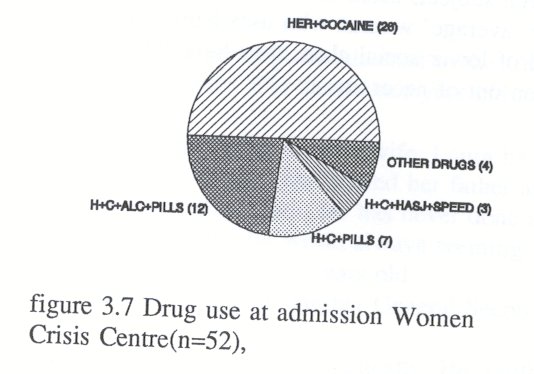

3.5 Drug-use

Almost all the subjects in the present study (n=52) are multiple drug-users. They use heroine, cocaine, medicines, methadone and alcohol. One woman uses the following substances every day: ten grammes of cocaine, one gramme of heroine and nineteen methadone tablets. She spends more than two thousand guilders a day on drugs. The research subject who spends the least buys thirty or forty guilders worth of drugs a day.

Most women spend a few hundred guilders each day on drugs. Figure 3.7 shows the drug-use-distribution.

Average years of drug-use

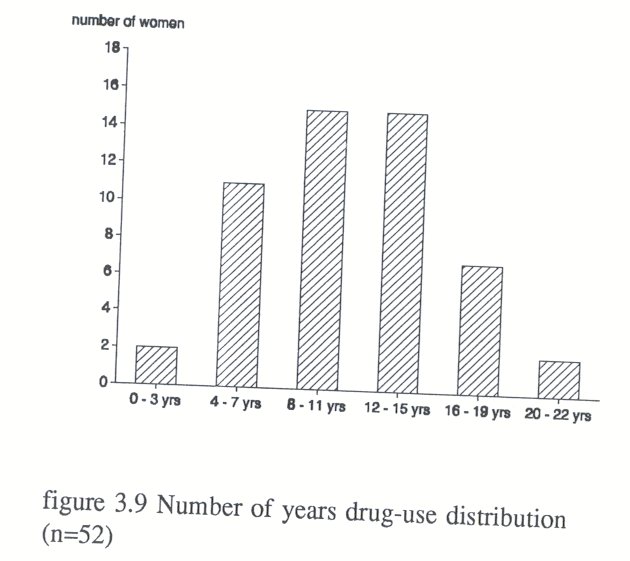

The average number of years of drug-use is eleven years (sd = 4,6). Figure 3.9 shows the number of years drug use-distribution

Ways of using hard drugs

Many research subjects (40 of 52) used the hard drugs intravenously. The other women smoked heroine or cocaine.

Starting with hard drugs

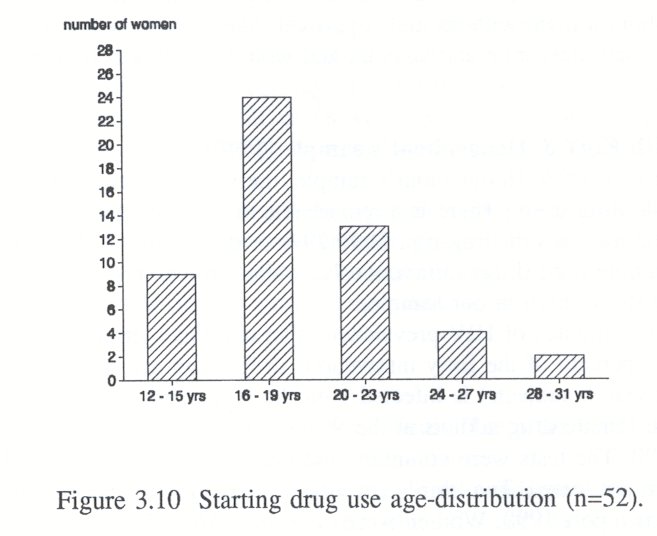

Almost half of the research subjects (24 of 52) began using hard drugs between the ages of sixteen and nineteen. Nine research subjects were younger, starting between the ages of twelve and fifteen. Only a few research subjects were older than 24 when they started using hard drugs. Figure 3.10 shows the distribution of age at which drug-use began.

The following case-history is illustrative of women who start taking drugs at an older age than usual. Drug-use is clearly not related to adolescence, but a way of coping with emotional and social problems.

Janine's story

When Janine was referred to the Women's crisis centre, she was 42 years old. She was desperate, because her children, nine years old and three years old, had been placed under judicial observation in a general hospital. There was suspicion that the children's father had committed incest with them.

Janine started taking heroine when she was 27 because her father had just died and she had recently got divorced. Her new boyfriend was a drug dealer who gave her drugs. She never uses drugs intravenously. When she uses drugs, she experiences positive sexual feelings, which she never had before. Drug-use relieved her of feelings of alienation and made her capable of expressing her feelings.

Janine is a middle child of ten children. When she was ten years old, her father, then aged 41, got himself a girlfriend of fourteen. He invited his young girlfriend to live with him in the house. Janine's mother did not resist, perhaps because her husband often beat her. Janine suffers from amnesia concerning the period from when she was three years old to six years old. She suspects her father sexually abused her, but remembers nothing about it. She knows that her brother once sexually assaulted her. Her father was a tight-mouthed, aggressive factory-worker. He died at the age of 58. Janine sees her mother as a gentle woman, a real mother and a good housewife.

Janine's first husband, a neighbour with two children, took advantage of her. He was a jealous alcoholic who physically abused her. Her second husband, by whom she had two children, also physically abused her and, at a time when they had no money, forced her into prostitution. She started to work as a prostitute when she was 37 years old. When she was 39 years old and pregnant, her husband beat her during her pregnancy.

She left him, but still meets him, speaks to him and gives him drugs. She cannot imagine life without a man, without male approval. She feels herself very dependent. She is depressed, desperate and suicidal and would like to kill both herself and her two children.

Comparison with Korf & Hoogenhout's sample (1990)

Like the women in Korf & Hoogenhout's sample, the women featured in the present study are multiple drug-users. There is a remarkable difference between the two groups with regard to the methods of drug-use. Only 29% of the women in Korf & Hoogenhout's sample used drugs intravenously, while intravenous drugs were used by three-quarters of the women in our sample.

According to estimates of HIV-prevalence (Van den Hoek et al., 1989), it can be presumed that 30 percent of the forty intravenous drug-using research subjects (12 women of the 52 research subjects) is infected with the HIV virus.

Thirty of the female drug addicts at the Women's crisis centre were tested for the HIV-virus in 1990. The tests were voluntary and half of the women at the Women's crisis centre were not tested. Two thirds (twenty women) tested positive for the HIV virus (annual year report 1990, Women's crisis centre). All HIV-infected women were intravenous drug-users. In 1990, three addicted women at the Women's Crisis Centre were suffering from Aids and exhibited severe somatic complaints.

3.6 Prostitution

Many research subjects (48 of 52) earned money from prostitution. They turn to prostitution (mean age 23, sd = 5,4) only after they start on drugs (between 16 and 19). The number of clients is often determined by the subject's need of drugs. Because the women drug-users are often unable to have sexual contact before taking drugs, they ask their clients to pay about fifty guilders in advance. They usually have about eight clients a day. If they are obviously ill with withdrawal symptoms, the price goes down. One or two research subjects said they made more money in private clubs. They said they earned two or three thousand guilders an evening when working in a private club. Usually the women are streetwalkers, though there are some exceptions. Sometimes they both work both on the street and in clubs (seven women). One woman works at Yab-Yum, a well-known brothel in Amsterdam. Another works for an escort service. Three women have worked in the Red Light District.

Four women named the high earnings as a positive aspect of prostitution. More then half of the research subjects (26 of 48 women) said they had exclusively negative experiences of prostitution. According to them, prostitution felt like rape. They were disgusted and felt ashamed.

Some research subjects said that their experiences in prostitution did not influence their private sex-life. They differentiated between private life and work, between boyfriend and client (6 research subjects). Sixteen research subjects did not like sex at all; prostitution had served only to increase their distaste or to cause them to lose interest in sex altogether.

The practice of safe sex

Nineteen research subjects used condoms with clients. The other research subjects did not answer this question or did not usually use condoms.

The research subjects were also asked if they used condoms with their boyfriends. Eight research subjects answered that their boyfriend did not like to use condoms and so they did not. Other contraceptive measures (taking the pill or using a contraceptive injection) also appeared to be sporadically.

Comparison with another sample

Keesmaat (1989) mentioned that three-quarters of women who used hard drugs were involved in prostitution. In the present study more than 90% of the women were involved in prostitution.

3.7 Crisis situation

The case histories, mentioned in section 3.4, show that the lives of female hard drugusers are filled with crisis situations. They had already experienced crisis situations at home long before they became addicted.

The Women's crisis centre initially used 'crisis situation' as a selection criterion. However, it soon became evident that 'crisis' was not useful as a selection criterion, because all drug-using women referred to the Crisis Centre live chronically in crisis

However, despite the fact that they lived chronically in crisis there was usually just one crisis too many which preceded admission.

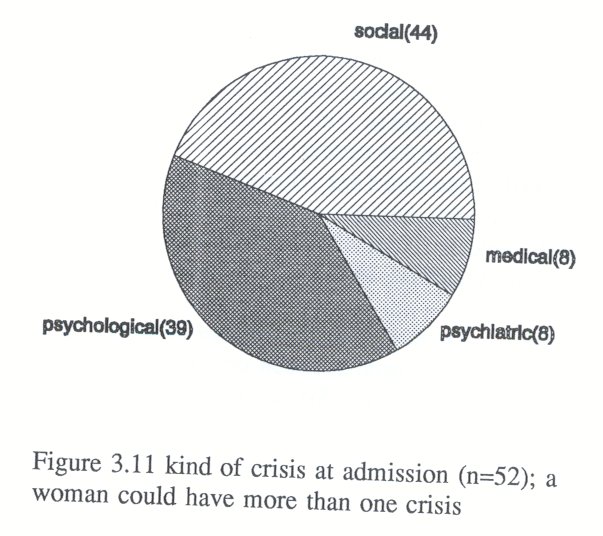

The most common crisis situations could be divided into four categories: a medical crisis, a social crisis, a psychological crisis and a psychiatric crisis. Figure 3.11 shows the distribution of the various crisis situations. Some women have two or three crises, for example a psychiatric crisis in conjunction with a medical or social crisis.

The crisis is classed as medical if the female drug-user is referred to the Crisis Centre because she is suffering from a somatic illness which is acute though not severe enough for admission to a hospital to be thought necessary. The following somatic illnesses required admission in the Women's crisis centre: miscarriage; advanced state of pregnancy; hepatitis A or B, Aids or being HIV-positive; abscess caused by intravenous drug-use; pneumonia or ovaritis. Other women referred to the Crisis Centre also suffered from somatic illnesses, but their medical problems did not come first. Eight women (15%) were admitted on medical grounds.

The crisis is classed as predominantly social if the problems concern housing, food and rest. These drug-using women are exhausted and need some time to recover. Some women are suffering only from a social crisis, but mostly the social crisis is linked with a psychological crisis. Exhaustion and lack of problem solving abilities or of seeing a way out lead to feelings of anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts. More than eighty percent of the women (42 of 52 women) were suffering from a social crisis. This is hardly surprising given the fact that three-quarters of the women did not have a roof over their heads.

The crisis is deemed to be predominantly psychological if a female drug-user is referred to the Crisis Centre because she is depressed and has lost control over her life.

She has given up the responsibility of caring for her own well-being. She is at risk of committing suicide. Three-quarters of the women are in psychological crisis.

If the female drug-user has lost contact with reality, if she is psychotic or very confused, the crisis is termed psychiatric. When in psychiatric crisis, the woman might suffer from psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions and extreme confusion. She is in need of psychiatric drugs and a psychiatrist is normally consulted for diagnosis and prescription. Eight women were suffering from a psychiatric crisis (15%). In general, such crises are chronic. Sometimes the symptoms worsen, a women wanders confused and naked on the street and is picked up by the police. She will then go from the police station to the Women's Crisis Centre, sometimes staying only a few hours, sometimes longer.

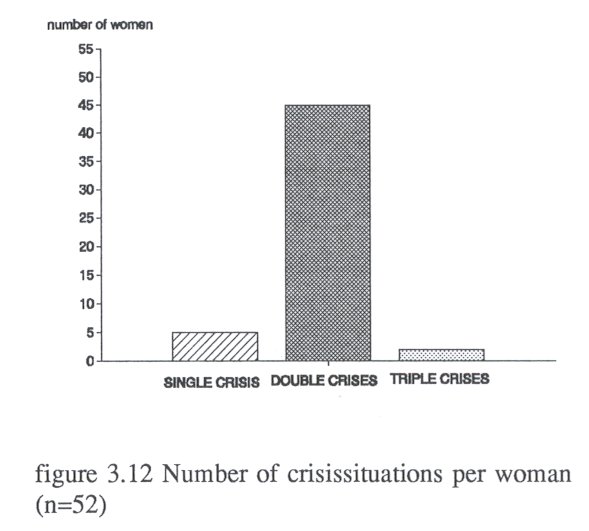

Figure 3.12 shows how many of the admission cases constitute single, double or triple crises.

In many cases a social crisis was coupled with a psychological crisis.

3.8 Summary

The social situation of the research subjects in the present study is on average inferior to that of other drug-using women. Self-destructive tendencies are more evident in the present group, they use drugs intravenously, are not medically insured and live in a condition of continuous social deprivation.

The paths to prostitution and addiction show that the path of 'prostitution out of necessity' is predominant. Most women are lower class or lower middle class with only primary school as education. Poor parenting, neglect, physical and sexual abuse, placement in foster care or boarding school and a gender-identity as society's female pariah are highly significant contributory factors to juvenile addiction and prostitution.

Many female drug-users act out of anger or grief caused by parental inadequacy, cruelty or neglect, which leaves them in a state of enraged worthlessness. These women, characterised as outcasts of society, are almost always the product of an unhappy childhood. This study did not find one woman from a stable, happy and loving family background who became addicted and a prostitute.

There is no possibility for the development of any basic trust; these women's lives shows a repetition of cruelty, neglect and assault.

Many female addicts have developed diverse strategies to survive the psychological consequences of childhood traumas. The next chapter is devoted to these strategies.

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|